Trader post scandal

The trader post scandal, or Indian Ring, that took place during Reconstruction, involved Secretary of War William W. Belknap and his wives, who received kickback payments derived from a Fort Sill tradership contract between Caleb P. Marsh and sutler John S. Evans. In 1870, Belknap lobbied Congress, and on July 15 of that year was granted the sole power to appoint and license sutlers with ownership rights to highly lucrative "traderships" at U.S. military forts on the Western frontier.[1][2] The power to appoint traderships by the Commanding General of the Army, at that time William T. Sherman, was repealed.[2] Having been granted the sole power to appoint traderships, Belknap further empowered those traderships with a virtual monopoly. Soldiers stationed at forts with Belknap-appointed sutlers could only buy supplies through the authorized tradership.[1] These monopoly traderships were considered to be excellent investments and were highly prized.[3] Soldiers on the Western frontier, who were thus forced to buy supplies at higher than market prices, were left destitute as a result.[4]

In 1870, Belknap's second wife, Carita, successfully lobbied her husband to appoint a New York contractor (Caleb P. Marsh) to the trader post at Fort Sill, located in the Indian Territory.[5] John S. Evans, however, had already been appointed to that position.[5] To settle the question of ownership, regarding the tradership, an illicit partnership contract, authorized by Belknap, was drawn. The contract allowed Evans to keep the tradership at Fort Sill, provided he paid $12,000 of the annual profits to Marsh. Evans would be allowed to keep the remaining profits.[5] Marsh, in turn, was required to split half of his receipts from the contract, $6,000 per year, with Carita. However, Carita only lived to receive one payment. In 1870, she died from tuberculosis, shortly after giving birth. After Carita's death, Marsh continued to pay Belknap Carita's share of the profits, for the benefit of her child.[5] Although the child died in 1871, Belknap continued to accept quarterly kickback payments from Marsh.[5] When Sec. Belknap subsequently remarried, to Carita's sister Amanda, both Belknap and Amanda continued to accept the quarterly payments from Marsh.[5]

On February 29, 1876, the U.S. Congress launched an extensive investigation run by Democratic Rep. Hiester Clymer's Committee into Belknap's War Department. The investigation discovered, through testimony, that profits from the Fort Sill tradership were split among Sec. Belknap, Marsh, Evans, and two of Sec. Belknap's wives, Carita and Amanda. On March 1, 1876, Sec. Belknap appeared before the committee but did not testify. The following morning, on March 2, 1876, in a White House meeting with President Ulysses S. Grant, Belknap tendered his resignation.

Grant's acceptance of Belknap's resignation was reported to Congress at 11:00 A.M. but did not deter the Clymer Committee from voting out articles of impeachment, which were forwarded to the full House that same day. The subsequent vote for impeachment was unanimous and was promptly forwarded to the Senate for trial.

In May 1876, after lengthy debate, the Senate voted that Belknap, a private citizen, could be put on trial by the Senate. Although there was strong evidence Belknap willingly accepted unlawful quarterly payments from Marsh, Belknap was acquitted when the vote for conviction failed to achieve the required two-thirds majority. Most of the Senators voting against conviction expressed the belief that the Senate had overstepped its authority in attempting to convict a private citizen.

The Congressional investigation by the House created a rift between President Ulysses S. Grant and Col. George A. Custer. Before and during the investigation, Col. Custer was associated with aiding and writing anonymous articles for the New York Herald that exposed trader post kickback rings and implied that Belknap was behind the rings. Moreover, during the investigation, Custer testified on hearsay evidence that President Grant's brother, Orvil, was involved in the trader post rings.

This infuriated President Grant who then, in retaliation, stripped Custer of his command in the campaign against the Dakota Sioux. Col. Custer however, lobbied Grant and was able to participate in the campaign against the Dakota Sioux.

However, Custer's reputation had been damaged. While attempting to restore his military prestige in the U.S. Army, Col. Custer was killed in action at the Battle of the Little Big Horn. Belknap had allowed the sale of superior military weapons to hostile Native Americans at trader posts, while having supplied soldiers in the U.S. Army defective military weapons. This upset the balance of firepower between Indians and U.S. soldiers, and may have contributed to the defeat of the U.S. military at the Battle of Little Big Horn.

In 1876, after Belknap's resignation, Grant appointed Alphonso Taft, as Secretary of War. Taft initiated a new protocol which only allowed fort commanders to appoint traderships.

Belknap appointed Secretary of War

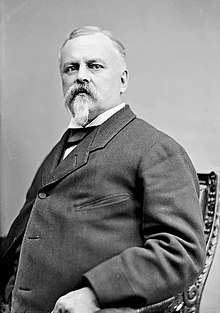

William W. Belknap (1869-1876)

A native of New York, and Iowa attorney, William W. Belknap entered the American Civil War in 1861 fighting for the Union.[1] Belknap, having efficiently served at Shiloh and Atlanta, was appointed major general by the end of the war.[1] Belknap was known for serving coolly under pressure at Shiloh and for bravely attacking a Confederate breastwork at Atlanta.[1] At the war's end in 1865 Belknap retired from the military and was appointed internal revenue collector in Keokuk; having served until 1869.[1] After Secretary of War John A. Rawlins died in 1869, President Ulysses S. Grant appointed Belknap to head the War Department.[1] Grant believed Belknap had served with honor and deserved a cabinet position.[6]

Tradership monopolies established

At the beginning of the war, Union soldiers began purchasing supplies from private vendors known as "sutlers".[1] These sutlers set up tradership posts inside U.S. Army forts and were chosen by the regimental officers to do business.[1] This policy changed in 1870, when Secretary of War Belknap lobbied Congress to pass a law vesting sole authority in the War Department to licence and choose sutlers at Western military forts. The authority previously granted to U.S. Army regimental officers, at the individual forts, was revoked.[1] Both U.S. Army soldiers and Indians shopped and bought supplies at these traderships.[3] These traderships controlled by Sec. Belknap became lucrative monopolies and considered profitable investments during the 1870s.[3]

Weapons sold to Indians

During Belknap's tenure American Indians, authorized by Grant's Indian peace policy, were sold top of the line breech-loaders and repeating rifles at the tradership posts on the Western frontier.[4] Violence on the Western frontier decreased starting in 1870 and lasting until 1875. The money Indians used to purchase weapons came from federal appropriations to keep Indians pacified.[3] Belknap to increase profits forced soldiers to only buy supplies from tradership monopolies at exorbitant prices and were left destitute.[7] This policy caught the ire of Col. George Custer stationed at Fort Lincoln who discovered most of the actual profits from the traderships were going to investors rather than the licensed sutlers. Belknap supplied soldiers defective breech-loading rifles that jammed after the third round.[8] This discrepancy in military weapons between hostile Indians and the U.S. Military was considered by one historian to be a significant factor in the defeat of the U.S. Military at the Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876.[8]

Fort Sill

In August 1870, Carita S. Tomlinson, the second wife of Belknap, lobbied on behalf of Caleb P. Marsh, to receive a tradership.[3][9] Having filled out and submitted an application on August 16, Sec. Belknap's War Department awarded Marsh a tradership at Fort Sill in the Oklahoma Territory.[3][9] John S. Evans, the experienced sutler already at Fort Sill, appointed on October 10, 1870, did not want to give up his lucrative trader post to Marsh.[9][10][11] An illicit financial arrangement, approved by Belknap, was made where Evans would keep the tradership and gave Marsh quarterly payments amounting to $12,000 per year.[9][10] Marsh then split this profit in half; giving $6,000 per year to Sec. Belknap's wife Carita in quarterly payments.[9][10] Evans would keep the remaining profits from the Fort Sill tradership.[9][10] Carita had come from a wealthy Kentucky family and was used to living in opulence.[9] It is believed that the kickback payments were intended to support this lavish lifestyle. However, Carita only lived to receive one payment. She died in December 1870 from tuberculosis, one month after giving birth to her child.[9][10] After Carita's death, Sec. Belknap and Carita's sister, Amanda Tomlinson Bower, who had previously moved in with Carita and Belknap, personally continued to take quarterly profit payments from Marsh.[9] Belknap eventually married Amanda in December 1873 and she became known as the "Queen" among cabinet member wives.[9][10] Caleb Marsh was the husband of one of Amanda's closest friends.[3] Amanda had, just as her sister Carita, enjoyed an opulent life style that cost a considerable amount of money during the Gilded Age.[3] Belknap's $8,000 yearly salary was unable to support his third wife's lavish spending habits.[3] When suspicious people asked Belknap how he could afford such a high standard of living on his salary, Belknap stated that Amanda, a wealthy widow, had received money from her deceased husband's estate.[3] In total, Sec. Belknap received more than $20,000 in payments derived from the Fort Sill tradership.[3] According to Congressional testimony, Belknap received money from other trading posts, as well.[3]

House investigation

National attention was drawn to the plight of American Indians in 1874 when paleontologist Othniel Marsh revealed that the Lakota Sioux had "frayed blankets, rotten beef and concrete-hard flour."[12] Secretary of Interior Columbus Delano, responsible for Indian Bureau policy, resigned office 1875.[12] The New York Herald, a Democratic newspaper, reported rumors that Sec. Belknap was receiving kick back money from tradership posts.[12] On February 29, 1876, during the Great Sioux War and a Presidential election year, Demrocratic Representative Hiester Clymer, a critic of Republican Reconstruction, launched an investigation into corruption in the War Department.[12] The Democratic Party had recently obtained a majority in the House of Representatives and immediately had begun a series of vigorous investigations into corruption charges of the Grant Administration.[13] Clymer's committee did not have far to look for corruption and information was soon gathered from witness testimony that Belknap and his wives had received illicit payments from the Fort Sill tradership contract. Apparently, in a discussion with Sec. Belknap, Rep. Clymer, who was friends with Belknap, advised Belknap to resign office in order to keep him from going to prison.[12] Sec. Belknap hired an attorney, Montgomery Blair.[12] Sec. Belknap defended himself by acknowledging that the payments took place, however, he stated that the financial arrangements were instigated by his two wives, unknown to himself.[12] Clymer, however, had an informant, Caleb Marsh, who exposed the Fort Sill ring under Congressional testimony.[12] Marsh testified under oath that he had directly made payments to Sec. Belknap and that Sec. Belknap gave Marsh receipts for these payments.[12]

Resignation of Belknap

Belknap with his counsel, Blair, testified before the Clymer Committee on February 29, 1876.[14] Belknap then withdrew from further testimony, and his attorney Blair proposed Congress drop charges against his client if Belknap resigned. The Clymer committee, however, was in no mood for compromise and declined.[14] On March 2, Rep. Lyman K. Bass informed former Solicitor General and current Treasury Secretary Benjamin Bristow, who informed Secretary of State Hamilton Fish, who in turn told him to tell President Grant.[14] When Bristow reached the White House, President Grant was eating breakfast and getting ready for a studio portrait session with Henry Ulke.[14] Bristow told President Grant of Belknap's tradership scheme and suggested he speak with Rep. Bass for further information.[14] After Bristow left, Grant scheduled an afternoon meeting with Congressman Bass.[14] He then began to leave for Ulke's studio when he was interrupted by Belknap and Interior Secretary Zachariah Chandler in the White House's Red Room.[15] Weeping, the burly Belknap prostrated himself before Grant and confessed to the kickback scheme, blaming his two wives. Belknap begged the President to accept his resignation.[15] Moved by Belknap's emotional plea, President Grant personally wrote and accepted Belknap's resignation at 10:20 A.M., much to Belknap's relief.[15] Immediately afterwards Senators Lot Morrill and Oliver Morton intercepted Grant and advised him not to accept Belknap's resignation; however, Belknap had already resigned.[15]

Belknap impeached by House

Despite Belknap's resignation, the House voted to impeach the former Secretary of War.[15] House members, however, argued over whether they had a right to impeach Belknap, now a private citizen.[15] Democratic Rep. Blackburn criticized Grant for accepting Belknap's resignation.[15] A false rumor spread that Belknap had committed suicide.[15] The House passed five articles of impeachment, to be presented to the Senate for trial.[16]

Custer testimony

Rep. Clymer continued his investigation into Belkamp's War Department, having called upon Col. George A. Custer, stationed at Fort Lincoln, who testified in Washington D.C. on March 29 and April 4.[17] Col. Custer was rumored to have anonymously aided the New York Herald in their investigation into Indian Traderpost rings,[17] particularly a March 31 New York Herald article, titled "Belknap's Anachonda".[17] Custer testified to Clymer's committee that sutlers (military post traders) gave a percentage of their profits to Sec. Belknap.[17] Custer had initially become suspicious in 1875 as his men at Fort Lincoln were paying high prices for supplies, and then found out the sutler at the fort was only being paid $2,000 out of the tradership's $15,000 in profits.[18] Custer believed that the $13,000 difference went to partners in the tradership, or to Belknap himself.[18] Custer said he had heard that President Grant's brother, Orvil, was involved in the tradership rings, having invested in three posts with the President's authorization.[17][19] President Grant was offended by the mention of Orvil Grant's name in that context.[19][20] Custer also testified that Col. William B. Hazen had been sent to a remote post, Fort Buford, as punishment for Hazen having exposed Belknap's traderpost rings in 1872.[21] This angered Philip Sheridan, who wrote to the War Department and contradicted Custer's claims, including concerning Hazen's reputed banishment.[21] Sheridan had been a staunch supporter of Custer until his testimony before the Clymer committee.[21] Although Custer's lengthy testimony was mostly hearsay, his reputation as military commander impressed the Clymer committee, Secretary of State Hamilton Fish, William T. Sherman, and the American press, and added significant weight to the hearings.[17] Belknap, despite his resignation, had strong connections in Washington, D.C. and used his influence to discredit Custer's testimony.[22]

Response of President Grant

President Grant's acceptance of Belknap's resignation on March 2, 1876, caused considerable commotion in the U.S. House of Representatives, since the House was ready to vote on Belknap's impeachment on the same day.[23] President Grant had Att. Gen. Pierrepont launch an investigation into Belknap; however, no charges were made by the Justice Department against Belknap.[24]

Protective of his family, Grant was furious that Custer testified against the President's brother Orvil at the Clymer committee hearings.[20] Sherman advised Custer to see Grant at the White House to talk over the situation; however, Grant refused on several occasions to see Custer.[25] Grant's refusal to see Custer was designed to humiliate the Colonel.[26] When Custer left to return to Fort Lincoln, Grant had Custer arrested in Chicago, since Custer left Washington without visiting Grant or Sherman, a breach of military protocol.[27] By Custer's own request, he was moved to Fort Lincoln under arrest to serve out his detention from active service.[27] President Grant relieved Custer from command of the expedition against the Lakota Sioux, eventually given to Alfred H. Terry by Sheridan, and forbade him from going on the expedition.[28] The Eastern press was outraged by Grant's actions against Custer and stated Grant had punished Custer for his testimony at the Clymer Committee.[28] After Custer wrote Grant a letter, from one soldier to another, to allow him to participate in the Sioux Expedition, Grant relented.[29] Custer had also gotten the reluctant endorsement of Sheridan, who knew that Custer was a skilled military leader.[30] Grant allowed Custer to join the expedition on the grounds that he would not take with him any pressmen.[30] Custer bragged he would "swing clear" of Terry's command once on the Expedition.[30]

Senate trial and acquittal

On March 3, 1876 a committee of five from the House of Representatives, headed by Rep. Hiester Clymer, presented to the Senate Belknap's articles of impeachment.[16] After much debate, on May 29, the Senate finally voted 37 to 29 that Belknap, as a private citizen, could not be barred from trial and impeachment.[31] Belknap's lengthy Senate trial, which took place in July, was very popular and the Senate gallery was filled with onlookers.[32] Unable to achieve the required two-thirds majority for conviction on any of the five impeachment articles, Belknap was finally acquitted by the Senate on August 1, 1876. Many of the Senators voting against conviction expressed the belief that a private citizen could not be impeached by the House or put on trial by the Senate.[32][33] President Grant's timely acceptance of Belknap's resignation had unquestionably saved Belknap from conviction.

Aftermath

After Belknap was acquitted by the Senate, he was indicted in Washington D.C. District Courts.[33] However, his case was not actively pursued, since actions under $40,000 rarely won prosecution.[33] Belknap, stigmatized by the House Impeachment and Senate trial, remained in Washington D.C. and made his living as an attorney.[24] President Grant replaced Belknap with the judicious and popularly received Alphonso Taft as Secretary of War.[24]

Belknap's wives

In 1854, Belknap married his first wife, Cora Le Roy, sister-in-law of Hugh T. Reid. Cora died in 1862.[1]

In January 1869, Belknap married a Kentucky "belle", Carita S. Tomlinson ("Carrie"), who died from tuberculosis in December 1870, after giving birth to their child.[10]

On December 11, 1873 Belknap married Carita's sister, Amanda Tomlinson Bower, a wealthy widow who would be popularly known for her high society status, extravagant spending, and beauty.[10]

References

- Koster (2010), p. 59

- Forty First Congress, Statutes At Large, pp. 319-320

- Koster, p.59-60

- Koster pp. 58-59

- McFeely (1974), p. 58

- Smith, p. 543

- Koster, pp 58, 60

- Koster, p. 58

- McFeely, pp. 428-429

- Koster, p. 60

- Trial of William W. Belknap, p. 555

- Koster, p. 61

- McFeely, p. 429

- McFeely, p. 433

- McFeely, pp. 433-434

- New York Times (March 4, 1876)

- Donovan, pp. 106–107

- Crowdy (2007), pp 110–111

- Koster, p. 64

- Donovan, pp. 110–111

- Donovan, pp. 108–109

- Donovan, p. 110

- McFeely, p. 434

- Smith (2001), p. 595

- Donovan, p. 111

- Donovan, p. 112

- Donovan, p. 111–112

- Donovan, pp. 112–113

- Donovan, pp. 113–114

- Donovan, pp. 114–115

- New York Times (May 20, 1876)

- McFeely, pp. 435-436

- New York Times (March 2, 1876)

Bibliography

Books

- Donovan, James (2008). A Terrible Glory: Custer and the Little Bighorn. New York, New York: Little, Brown, and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-15578-6.

- McFeely, William S. (1981). Grant: A Biography. New York, New York: W.W. Norton & Company, LTD. ISBN 0-393-01372-3.

- Oberholtzer, Ellis Paxson (1926). A History of the United States since the Civil War. 3. pp. 159–70.

- Smith, Jean Edward (2001). Grant. New York, New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-84927-5.

Articles

- Koster, John (June 2010). "The Belknap Scandal Fulcrum to Disaster". Wild West: 58–64.

Newspapers

- "The Proceedings in the Senate". The New York Times. March 4, 1876.

- "Gen. Belknap's Impeachment". The New York Times. May 30, 1876.

- "Acquittal of Belknap". The New York Times. August 2, 1876.

Primary

- "Trial of William W. Belknap". Proceedings of the Senate. Washington Government Printing Office. 1876.

External links

- United States Senate May 1876 War Secretary's Impeachment Trial

- William W. Belknap: shell game