Little Pigeon Creek Community

Little Pigeon Creek Community, also known as Little Pigeon Creek Settlement and Little Pigeon River settlement, was a settlement in present Carter and Clay Townships,[1]:271–272,412[2] Spencer County, Indiana along Little Pigeon Creek.[3] The community, in the area of present-day Lincoln City, Indiana,[1][lower-alpha 1] was established from frontier land by 1816.[4] There were sufficient settlers to the Indiana wilderness that it became a state in December, 1816.[5]:22

Overview

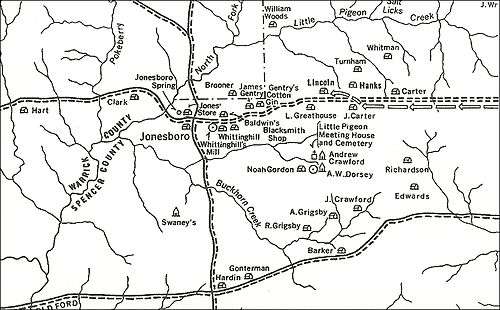

In 1820 there were 40 or more families, including Abraham Lincoln's family, that lived in the community.[3][lower-alpha 2] Living within 1100 feet of the Lincolns were Dennis and Elizabeth Hanks and the Casebier and the Barrett families.[7] Most of the families—like the Lincolns, Carters and Gordons—had moved to the area from Hardin County, Kentucky.[3]

Although there were also a number of families nearby, it was a "scattered rural settlement", rather than a village.[7] Amongst the farms were a church, general store and post office, schools,[8] and Noah Gordon's mill,[2][8]:5 which ground corn. The mill was operated by horse power.[8]:6 James Gentry, the namesake for nearby Gentryville, operated a 1000-acre farm and store. Abraham was a clerk at the store and ferried goods to New Orleans for Gentry.[8]:6–7 An east–west dirt road to Troy on the Ohio River traversed through the community.[9][8]:7 The roadbed crosses the Lincoln State Park and parts of the road are part of the parks trail system.[8]:7

Church and schools

_(14596912157).jpg)

The Little Pigeon Primitive Baptist Church, a Regular Baptists congregation, was established June 8, 1816 with 15 charter members.[10] Thomas Lincoln, Abraham's father, helped build the cabin for the church in 1819, located south of present-day Lincoln City, Indiana[11][1] and in the center of the community near a spring. The land was donated by Samuel Howell.[8]:5 The log meetinghouse, completed in 1822, had split log benches for its congregation. Attending church was a social event where the settlers could discuss family life events, farming, the weather, land titles, and other current events.[5]:24 The church building was also used as a school.[1]:412 A second church building was erected in 1879.[11] The current church building, which has continued to conduct services, was erected in 1948.[8]:5 The church's cemetery, built in 1825, is the grave site of the communities settlers, including Abraham's sister, Sarah Lincoln Grigsby.[2][8]:6

After the church was built, school was conducted there during the winter. Teachers were paid in meat, produce and animal skins.[5]:23 Schools in the community included the one-room Andrew Crawford School, which was still standing in 1865; Swaney or Sweeney School, and the Dorsey School.[8]:7

Frontier

Settlers cleared the forests of hickory and oak trees for farming. Within a few years the settlement was mostly farmland.[8]:4[lower-alpha 3]

The game in what Abraham Lincoln called the "unbroken forest" and "wild region" included bears, wolves,[12] squirrels, partridges, hawks, wild cats, turkey, sparrows, and crows.[5]:24 Lincoln said in a poem:

- When my father settled here,

- 'Twas then the frontier line.

- The panther's scream, filled night with fear,

- And bears preyed on the swine.

— Abraham Lincoln[12]

Dennis Hanks stated that the settlers could be "very ruff". In its early days the settlers worked and supported one another, but there was also immoral, drunken, thieving, and superstitious behavior.[12]

Lincolns

Thomas and Nancy Lincoln—along with their children Sarah and Abraham—moved to the Little Pigeon Creek settlement in the winter of 1816.[4] Their homestead was within the present Lincoln City, Indiana.[1]:426 The Lincolns lived in a half-faced camp or poleshed[5]:20[lower-alpha 4] and ate wild game, corn and pork until they built a log house and began to farm the land in 1817.[4] Late 1817 the Lincolns were joined by Tom and Elizabeth Sparrow, who had raised Nancy,[12][5]:22 and Dennis Hanks, Abraham's cousin, from Kentucky. They lived in the Lincoln's shed until their home was built.[5]:22,23

In October 1818, Nancy died of milk sickness[lower-alpha 5] and was buried within a half mile of the homestead.[4] Tom and Elizabeth Sparrow died of milk sickness a few weeks before Nancy's death and they are all buried together.[5]:22 Late the following year Thomas married Sarah Bush Lincoln, a widow from Kentucky who had three children.[4][13] Tom and Sarah had known each other in Kentucky and he had traveled to Elizabethtown, Kentucky to ask her to marry him.[5]:23

Abraham wrote of his childhood in Indiana, "We reached our new home about the time the State came into the Union. It was a wild region, with many bears and other wild animals still in the woods. There I grew up. There were some schools, so called; but no qualification was ever required of a teacher, beyond 'readin, writin, and cipherin,' to the Rule of Three."[4] Abraham Lincoln lived at the Indiana farm from 1816 to 1830.[14]

In 1879, a headstone was placed at Nancy's probable grave site. The state of Indiana opened the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial, including the marked location of the Lincoln's house. In the 1930s, Indiana also developed the adjacent Lincoln State Park as a recreation and scenic area. Between 1940 and 1944, the state build a memorial building, designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr.. The memorial building and the reconstructed Lincoln homestead, sitting on 100 acres, were created in the 1960s as the Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial.[4]

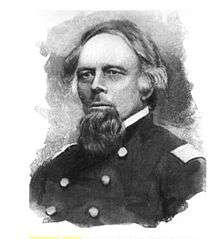

Colonel William Jones

William Jones operated a store and had a cabin in the community. He sold and bartered merchandise and shipped farmer's grain, tobacco, hides, pork, venison, and beef to New Orleans on flatboats. He also became a postmaster.[8][6] Jones employed Abraham Lincoln who lived a few miles from Jones[15] and was hired to butcher and process meat and unpack boxes[8] in 1829.[16] Lincoln read all of Jones' books and Jones remarked that "Lincoln would make a great man one of these days."[17]

Jones built the Colonel William Jones House across the street from his cabin around 1834 when his business endeavors made him wealthy. The one-story brick house is a Federal style house with Classical Revival features, including a Greek columned front porch and pediment. It has a captain's walk on the roof and a small loft.[8] Lincoln's father, Thomas Lincoln, is said to have built the corner cupboard in the kitchen.[15] It sits on one of the area's highest points.[8] The Lincoln State Park Improvement Plan of 2005 states that "[t]he Jones Home is an example of the increased affluence and changing economy during this period. The Jones Home represents those successful entrepreneurs who stayed in Southern Indiana instead of moving further west.[8]

Jones moved to Gentryville in the early 1850s and the house then went through several owners. In 1887 the house was bought by George and Arietta Bullock and remained in the Bullock family until 1976 when it was purchased by Gayle and Bill Cook who restored the house. It was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1975. The house and 100 acres were transferred in 1990 to the Indiana Department of Natural Resources (IDNR).[8]

Jones was elected in 1838 to the Indiana General Assembly, where he supported internal improvements and economic development[8] and served until 1841.[17] Jones was a supporter of a Whig, Henry Clay and was "incapacitated" for several days when Clay lost the presidential election. Lincoln, who was then an Illinois elector became a Whig, had heard Jones political views and campaigned. Lincoln made speeches for Clay in 1844[8] and stayed at the Jones House at that time.[17] Jones and Lincoln both became Republicans when the Whig party was terminated.[8]

In the 1850s, Jones moved to Gentryville, Indiana and opened another store.[8] Jones was a Union Colonel[11] during the Civil War.[17] He received battle honors for his service at Meridian Expedition, Siege of Corinth, and Battle of Atlanta, where he died on July 22, 1864.[8][17]

Name

The area and the creek were named for the breeding ground of southern Indiana passenger pigeons, now extinct. They had been so great in number that they "literally formed clouds, and floated through the air in a frequent succession of these as far as the eye could reach, sometimes causing a sensible gust of wind, and a considerable motion of the trees over which they flew." John James Audubon observed, "Multitudes are seen, sometimes in groups, at the estimate of a hundred and sixty-three flocks in 21 minutes. The noonday light is then darkened as by an eclipse, and the air filled with the dreamy buzzing of their wings."[3]

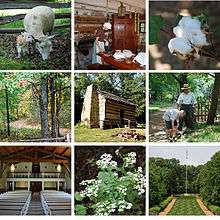

Gallery

_(14783424525).jpg) Little Pigeon Baptist Church and gravestone of Sarah Lincoln Grigsby, Abraham's sister (1909)

Little Pigeon Baptist Church and gravestone of Sarah Lincoln Grigsby, Abraham's sister (1909)

See also

- Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial

- Lincoln Pioneer Village, which has replicas of buildings from the Little Pigeon Creek Community

- Lincoln State Park, the site of the Lincoln home, a replica of their house and buildings from the Little Pigeon Creek Community

Notes

- Lincoln City, named for the nearby Lincoln homestead and the Nancy Lincoln grave site, was laid out in 1874. It was built to support the railroad industry and had a hotel, saloon, store, blacksmith, and physicians.[1]:365

- Within a mile radius of the Lincolns there lived Thomass Barrett, with four children; Thomas Turnham with three; Thomas Carter with six; John Carter with eight; John Jones with four; and probably John Romine with four. Including the Lincoln children, there were a total of nine families with 49 children - 15 boys and 13 girls under the age of 7, 12 boys and 9 girls between the ages of 7 and 17. Beyond the one mile radius, but within two miles of the Lincolns lived the Joseph Wright and William Wright families and the Noah Gordon, James Gentry, and William Whittinghill families. Between the two and three miles radius lived the John Blair, Rueben Grigsby, William Jones, and Peter Brooner families. Those residing about four miles from the Lincolns were the Lawrence Jones, William Stark, William Smith, Henry Gunterman, John Hoskins, Jacob Hoskins, David Winkler, and Joseph Hoskins families. The total number of children within a four-mile radius was 45 boys and 45 girls under the age of 7 and 23 boys and 25 girls between the ages of 7 to 17.[6]

- In the 1930s the Civilian Conservation Corps planted trees to reforest what is now the Lincoln State Park.[8]:4

- The half-faced camp was a 14 foot square, three-sided shelter made of logs with the open side facing a campfire that provided a measure of warmth.[5]:20[13]

- Milk sickness had been an epidemic in southern Indiana in 1818, killing cows and humans. At the time, it was not known that the disease transmitted when cows ate toxic weeds.[12]

References

- History of Warrick, Spencer, and Perry Counties, Indiana: From the Earliest Time to the Present. Goodspeed. 1885. p. 366. Retrieved October 4, 2015.

Lincoln.

- Katie Martin. "Abraham Lincoln's Indiana Legacy". America's State Parks. Archived from the original on December 3, 2015. Retrieved October 4, 2015.

- "Little Pigeon Creek - Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial, Indiana". National Park Service. Retrieved October 4, 2015.

- "Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial". National Park Service. Retrieved October 4, 2015.

- Carl Sandburg, Edward C. Goodman (2007). Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years and the War Years. Sterling Publishing Company. pp. 20, 22. Retrieved October 4, 2015.

- "Little Pigeon Creek Families - Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial, Indiana". National Park Service. Retrieved October 4, 2015.

- Olivier Frayssé (1994). Lincoln, Land, and Labor, 1809-60. University of Illinois Press. pp. 36–37. Retrieved October 4, 2015.

- "Lincoln State Park Interpretive Master Plan 2005" (PDF). Indiana Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved October 4, 2015.

- "Little Pigeon Creek Settlement ("Abe's Neighborhood") map". Retrieved October 4, 2015.

- "Pigeon Creek Church". Lincoln Lore. Fort Wayne, Indiana (661). December 8, 1941. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- "Little Pigeon Primitive Baptist Church". Friends of Lincoln State Park. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved October 4, 2015.

- Michael Burlingame (November 6, 2012). Abraham Lincoln: A Life, Volume 1. JHU Press. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- Gertrude van Duyn Southworth. "Abraham Lincoln Before 1861". Builders of Our Country: Book II. The Baldwin Project, Yesterday's Classics. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- "Little Pigeon Creek - Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial, Indiana - History & Culture". National Park Service. Retrieved October 4, 2015.

- Don Davenport (January 1, 2002). In Lincoln's Footsteps: A Historical Guide to the Lincoln Sites in Illinois, Indiana, and Kentucky. Trails Books. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-931599-05-4.

- Roger D. Hunt (November 12, 2013). Colonels in Blue--Indiana, Kentucky and Tennessee: A Civil War Biographical Dictionary. McFarland. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-1-4766-1386-4.

- "Colonel William Jones Historic Site". Abraham Lincoln Online. Retrieved October 5, 2015.