French Revolution

The French Revolution (French: Révolution française [ʁevɔlysjɔ̃ fʁɑ̃sɛːz]) was a period of social and political upheaval in France and its colonies beginning in 1789 and ending in 1799. The Revolution overthrew the monarchy; established a republic; catalyzed violent periods of political turmoil; and finally culminated in a dictatorship under Napoleon, who brought many of the revolution's principles to areas he conquered in Western Europe and beyond. Inspired by liberal and radical ideas such as equality before the law, the Revolution influenced the decline of absolute monarchies while replacing them with republics and liberal democracies.[1]

| Part of the Atlantic Revolutions | |

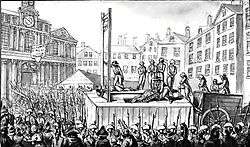

The Storming of the Bastille, 14 July 1789 | |

| Date | 5 May 1789 – 9 November 1799 (10 years, 6 months and 4 days) |

|---|---|

| Location | Kingdom of France |

| Outcome |

|

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of France | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

20th century

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

The causes of the French Revolution are complex and are still debated among historians. The American Revolution helped set the stage for the events of the French Revolution, having shown France that a rebellion based on Enlightenment principles, including natural rights and equality for all citizens, against an authoritarian regime could succeed. German diplomat Friedrich von Gentz (1764-1832) observed in a treatise published in France in 1800:

The example of this undertaking, crowned with the most complete success, must have had a more immediate and powerful influence upon those, who destroyed the old government of France, than the example of any earlier European revolution: the circumstances, in which France was, at the breaking out of her revolution, had been, if not wholly, yet for the greatest part brought on by the part she had taken in that of America. In the conduct and language of most of the founders of the French revolution, it was impossible not to perceive an endeavour to imitate the course, the plans, the measures, the forms, and, in part, the language of those, who had conducted that of America; and to consider this, upon all occasions, as at once the model, and the justification of their own.[2][3]

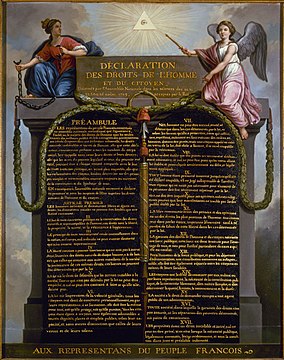

The National Assembly of France even used the American Declaration of Independence as a template when drafting the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in 1789. The American success in their revolution may have been the "single greatest impact" on the start of the French Revolution.[4]

Following the Seven Years' War and the American Revolutionary War,[5] the French government was deeply in debt. It attempted to restore its financial status through unpopular taxation schemes, which were heavily regressive. Leading up to the Revolution, years of bad harvests worsened by deregulation of the grain industry and fifty consecutive days of below-freezing temperatures in the winter of 1788/1789 inflamed popular resentment of the privileges enjoyed by the aristocracy and the Catholic clergy of the established church. Demands for change were formulated in terms of Enlightenment ideals on democracy, and contributed to the convocation of the Estates General in May 1789. During the first year of the Revolution, members of the Third Estate (commoners) took control; the Bastille was attacked in July; the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen was passed in August; and the Women's March on Versailles forced the royal court back to Paris in October. A central event of the first stage, in August 1789, was the abolition of feudalism and the old rules and privileges left over from the Ancien Régime.

The next few years featured political struggles between various liberal assemblies and supporters of the monarchy intent on thwarting major reforms, promoted by the Jacobins, led to the Insurrection of 10 August 1792 and the arrest of Louis XVI and the royal family. The Republic was proclaimed in 22 September after the first French elections and the victory at Valmy. Its goal was to unify France and to introduce the same taxes and democratic elections for more citizens. It opposed prerogatives. In a momentous event that led to international condemnation and an internal struggle in the Convention between the Girondins and Montagnards, Louis XVI was executed in January 1793.

External threats closely shaped the course of the Revolution. The French Revolutionary Wars unleashed a wave of global conflicts that extended from the Caribbean to the Middle East. Internally, popular agitation by the Sans-culottes radicalised the Revolution significantly, followed by the Insurrection at the end of May, and the rise of Maximilien Robespierre. A levée en masse, an army of volunteers to beat the external and internal enemy, culminated in a federalist revolt in the South and the West. The dictatorship imposed by the Committee of Public Safety established price controls on food and soap, introduced a secular Republican calendar, de-established the Catholic church (dechristianised society). During what was called the Reign of Terror, counter-revolutionaries were expelled, arrested or executed; and the borders of the new republic were secured from its enemies.

After the Fall of Robespierre and Thermidorian Reaction, an executive council known as the Directory assumed control of the French state in 1795. They suspended elections, repudiated debts (creating financial instability in the process), persecuted the Catholic clergy, and made significant military conquests on the Italian Peninsula.[6]:393–7 Dogged by charges of corruption, the Directory collapsed in a coup led by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1799. Napoleon, who ended and became the hero of the Revolution, established the Consulate and later the First French Empire.

Many future revolutionary movements were influenced by the French Revolution.[6]:361 For example, its central phrases and cultural symbols, such as La Marseillaise and Liberté, fraternité, égalité, ou la mort, became the clarion call for other major upheavals in modern history, including the Russian Revolution over a century later.[7] Some of its central documents, such as the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, continued to inspire movements for abolitionism and universal suffrage in the next two centuries.[8]

The Revolution resulted in the suppression of the feudal system, emancipation of the individual, a greater division of landed property, abolition of the privileges of noble birth, and nominal establishment of equality among men. The Revolution also witnessed the birth of total war by organising the resources of France and the lives of its citizens towards the objective of national defence.[9] Globally, the Revolution became the focal point for the development of most modern political ideologies, leading to the spread of liberalism, radicalism, nationalism, and secularism, among many others, accelerating the rise of republics and democracies. The values and institutions of the Revolution dominate French politics to this day. Many historians regard the Revolution as one of the most important events in human history.[10][11][6]:341

Causes

%2C_rev%C3%AAtu_du_grand_costume_royal_en_1779_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

Historians have pointed to many events and factors within the Ancien Régime that led to the Revolution. Rising social and economic inequality;[12][13] new political ideas emerging from the Enlightenment;[14] economic mismanagement; environmental factors leading to agricultural failure, unmanageable national debt;[15] and political mismanagement on the part of King Louis XVI, have all been cited as laying the groundwork for the Revolution.[16][17][18][19]

Over the course of the 18th century, there emerged what the philosopher Jürgen Habermas called the idea of the "public sphere" in France and elsewhere in Europe.[20]:26 Habermas argued that the dominant cultural model in 17th-century France was a "representational" culture, which was based on a one-sided need to "represent" power with one side active and the other passive.[20]:26 A perfect example would be the Palace of Versailles, which was meant to overwhelm the senses of the visitor and convince one of the greatness of the French state and Louis XIV.[20]:26 Starting in the early 18th century the "public sphere" emerged which was "critical" in that both sides were active.[20]:26–7 Examples of the public sphere included newspapers, journals, masonic lodges, coffee houses and reading clubs where people either in person or virtually via the printed word debated and discussed issues.[20]:27 In France, the emergence of the public sphere outside of the control of the state led to the shift from Versailles to Paris as the cultural capital of France.[20]:27 Likewise, while in the 17th century the court had decided what was culturally good and what was not, in the 18th century the opinion of the court mattered less and consumers became the arbiters of cultural taste.[20]:28 In the 1750s, during the "Querelle des Bouffons" over the question of the quality of Italian vs. French music, the partisans of both sides appealed to the French public "because it alone has the right to decide whether a work will be preserved for posterity or will be used by grocers as wrapping-paper."[20]:29 In 1782, Louis-Sébastien Mercier wrote: "The word court no longer inspires awe amongst us as in the time of Louis XIV. Reigning opinions are no longer received from the court; it no longer decides on reputations of any sort ... The court's judgments are countermanded; one says openly that it understands nothing; it has no ideas on the subject and could have none."[20]:26–7 Inevitably, the belief that public opinion had the right to decide cultural questions instead of deferring to the court transformed itself into the demand that the public also have a say on political questions as well.[20]:29–30

The economy in the Ancien Régime during the years preceding the Revolution suffered from instability. The sequence of events leading to the Revolution included the national government's fiscal troubles caused by an unjust, inefficient and deeply hated tax system—the ferme générale—and by expenditure on numerous large wars.[15] The attempt to challenge British naval and commercial power in the Seven Years' War was a costly disaster, with the loss of France's colonial possessions in continental North America and the destruction of the French Navy.[21] French forces were rebuilt, and feeling bitter about having lost many of France's overseas colonies to the British Empire during the Seven Years' War, Louis XVI was eager to give the American rebels financial and military support. After the British surrender at the Battle of Saratoga, the French sent 10,000 troops and millions of dollars to the rebels. Despite succeeding in gaining independence for the Thirteen Colonies, France was severely indebted by the American Revolutionary War. France's inefficient and antiquated financial system could not finance this debt.[22] Faced with a financial crisis, the king called an Estates General, recommended by the Assembly of Notables in 1787 for the first time in over a century.[23]

France was experiencing such a severe economic depression that there wasn't enough food to go around. Poor harvests lasting several years and an inadequate transportation system both contributed to making food more expensive.[24][25] As with most monarchies, the upper class was always ensured a stable living, so while the rich remained very wealthy, the majority of the French population was starving. Many were so destitute that they couldn't even feed their families and resorted to theft or prostitution to stay alive. Meanwhile, the royal court at Versailles was isolated from and indifferent to the escalating crisis. While in theory King Louis XVI was an absolute monarch, in practice he was often indecisive and known to back down when faced with strong opposition. While he did reduce government expenditures, opponents in the parlements successfully thwarted his attempts at enacting much needed reforms. The Enlightenment had produced many writers, pamphleteers and publishers who could inform or inflame public opinion. The opposition used this resource to mobilise public opinion against the monarchy, which in turn tried to repress the underground literature.[22]

Many other factors involved resentments and aspirations given focus by the rise of Enlightenment ideals. These included resentment of royal absolutism; resentment by peasants, labourers and the bourgeoisie towards the traditional seigneurial privileges possessed by the nobility; resentment of the Catholic Church's influence over public policy and institutions; aspirations for freedom of religion; resentment of aristocratic bishops by the poorer rural clergy; aspirations for social, political and economic equality, and (especially as the Revolution progressed) republicanism; hatred of Queen Marie-Antoinette, who was falsely accused of being a spendthrift and an Austrian spy; and anger towards the King for dismissing ministers, including finance minister Jacques Necker, who were popularly seen as representatives of the people.[26]

Ancien Régime

Financial crisis

In 1774 Louis XVI ascended to the throne in the middle of a financial crisis in which the state was faced with a budget deficit and was nearing bankruptcy.[27] This was due in part to France's costly involvements in the Seven Years' War and later the American Revolutionary War.[28] In May 1776, finance minister Turgot was dismissed, after failing to enact reforms. The next year, Jacques Necker, a foreigner, was appointed Comptroller-General of Finance. He could not be made an official minister because he was a Protestant.[29]

Necker realised that the country's extremely regressive tax system subjected the lower classes to a heavy burden,[29] while numerous exemptions existed for the nobility and clergy.[30] He argued that the country could not be taxed higher; that tax exemptions for the nobility and clergy must be reduced; and proposed that borrowing more money would solve the country's fiscal shortages. Necker published a report to support this claim that underestimated the deficit by roughly 36 million livres, and proposed restricting the power of the parlements.[29]

This was not received well by the King's ministers, and Necker, hoping to bolster his position, argued to be made a minister. The King refused, Necker was dismissed, and Charles Alexandre de Calonne was appointed to the Comptrollership.[29] Calonne initially spent liberally, but he quickly realised the critical financial situation and proposed a new tax code.[31]

The proposal included a consistent land tax, which would include taxation of the nobility and clergy. Faced with opposition from the parlements, Calonne organised the summoning of the Assembly of Notables. But the Assembly failed to endorse Calonne's proposals and instead weakened his position through its criticism. The Notables concluded that this kind of change must be approved by the people in the form of the Estates-General.

His failures resulted in Calonne's dismissal, and in May 1787 he was replaced with Brienne. Brienne presented a package to the Notables that was not dissimilar to Calonne's, but without the sale of church land. This was again rejected and the Notables dissolved. Brienne attempted to appeal this judgement by sending his reforms to the Parlement in early June; the Parlement endorsed the principal of the reforms, but like the Notables, concluded that the changes could only be made by the Estates-General. They announced their decision in July, following the Day of the Tiles, a formal resistance by the people to Brienne and the King's efforts to push reforms. Louis attempted to compel the Parlement to approve the reforms via a lit de justice, which the Parlement declared invalid.[32]

A Royal Session was called for 19 November 1787, between the Parlement and the King. The Parlement resisted royal mandate even in King's presence. In response, the King had no choice but to announce the calling of the Estates-General for May 1789, the first time the body had been summoned since 1614. This was a signal that the Bourbon monarchy was in a weakened state and subject to the demands of its people.[33]

Estates-General of 1789

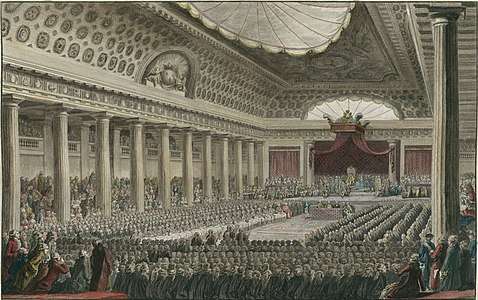

The Estates-General was organised into three estates: the clergy, the nobility, and the rest of France. It had last met in 1614. Elections were held in the spring of 1789; suffrage requirements for the Third Estate were for French-born or naturalised males, aged 25 years or more, who resided where the vote was to take place and who paid taxes. Strong turnout produced 1,201 delegates, including 303 clergy, 291 nobles and 610 members of the Third Estate. The First Estate represented 100,000 Catholic clergy; the Church owned about 10% of the land and collected its own taxes (the tithe) on peasants. The lands were controlled by bishops and abbots of monasteries, but two-thirds of the 303 delegates from the First Estate were ordinary parish priests; only 51 were bishops.[34] The Second Estate represented the nobility, about 400,000 men and women who owned about 25% of the land and collected seigneurial dues and rents from their peasant tenants. About a third of these deputies were nobles, mostly with minor holdings. The Third Estate representation was doubled to 610 men, representing 95% of the population. Half were well educated lawyers or local officials. Nearly a third were in trades or industry; 51 were wealthy land owners.[35][36]

To assist delegates, "Books of grievances" (cahiers de doléances) were compiled to list problems.[37] The books articulated ideas which would have seemed radical only months before; however, most supported the monarchical system in general. Many assumed the Estates-General would approve future taxes, and Enlightenment ideals were relatively rare.[38][39]

Pamphlets by liberal nobles and clergy became widespread after the lifting of press censorship.[40] The Abbé Sieyès, a theorist and Catholic clergyman, argued the paramount importance of the Third Estate in the pamphlet Qu'est-ce que le tiers état? (What is the Third Estate?) published in January 1789. He asserted: "What is the Third Estate? Everything. What has it been until now in the political order? Nothing. What does it want to be? Something."[41]

The Estates-General convened in the Grands Salles des Menus-Plaisirs in Versailles on 5 May 1789 and opened with a three-hour speech by Necker. The Third Estate demanded that the credentials of deputies should be verified by all deputies, rather than each estate verifying the credentials of its own members, but negotiations with the other estates failed to achieve this. The commoners appealed to the clergy, who asked for more time. Necker then stated that each estate should verify its own members' credentials and that the king should act as arbitrator.[42]

National Assembly (1789)

On 10 June 1789 Abbé Sieyès moved that the Third Estate, now meeting as the Communes (English: "Commons") proceed with verifying its own powers and invite the other two estates to take part, but not to wait for them. They proceeded to do so two days later, completing the process on 17 June.[43] Then they voted a measure far more radical, declaring themselves the National Assembly, an assembly not of the Estates but of "the People". They invited the other orders to join them, but made it clear they intended to conduct the nation's affairs with or without them.[44]

In an attempt to keep control of the process and prevent the Assembly from convening, Louis XVI ordered the closure of the Salle des États where the Assembly met, making an excuse that the carpenters needed to prepare the hall for a royal speech in two days. Weather did not allow an outdoor meeting, and fearing an attack ordered by Louis XVI, they met in a tennis court just outside Versailles, where they proceeded to swear the Tennis Court Oath (20 June 1789) under which they agreed not to separate until they had given France a constitution. A majority of the representatives of the clergy soon joined them, as did 47 members of the nobility. By 27 June, the royal party had overtly given in, although the military began to arrive in large numbers around Paris and Versailles. Messages of support for the Assembly poured in from Paris and other French cities.[45]

Constitutional monarchy

National Constituent Assembly (Jul. 1789 – Sept. 1791)

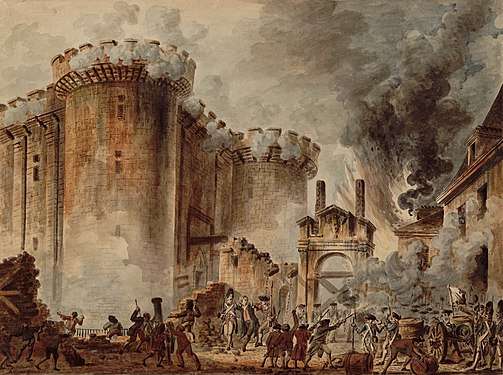

Storming of the Bastille

By this time, Necker had earned the enmity of many members of the French court for his overt manipulation of public opinion. Marie Antoinette, the King's younger brother the Comte d'Artois, and other conservative members of the King's privy council urged him to dismiss Necker as financial advisor. On 11 July 1789, after Necker published an inaccurate account of the government's debts and made it available to the public, the King fired him, and completely restructured the finance ministry at the same time.[46]

Many Parisians presumed Louis' actions to be aimed against the Assembly and began open rebellion when they heard the news the next day. They were also afraid that arriving soldiers – mostly foreign mercenaries – had been summoned to shut down the National Constituent Assembly. The Assembly, meeting at Versailles, went into nonstop session to prevent another eviction from their meeting place. Paris was soon consumed by riots, chaos, and widespread looting. The mobs soon had the support of some of the French Guard, who were armed and trained soldiers.[47]

On 14 July, the insurgents set their eyes on the large weapons and ammunition cache inside the Bastille fortress, which was also perceived to be a symbol of royal power. After several hours of combat, the prison fell that afternoon. Despite ordering a ceasefire, which prevented a mutual massacre, Governor Marquis Bernard-René de Launay was beaten, stabbed and decapitated; his head was placed on a pike and paraded about the city. Although the fortress had held only seven prisoners (four forgers, two noblemen kept for immoral behaviour, and a murder suspect) the Bastille served as a potent symbol of everything hated under the Ancien Régime. Returning to the Hôtel de Ville (city hall), the mob accused the prévôt des marchands (roughly, mayor) Jacques de Flesselles of treachery and butchered him.[48]

The King, alarmed by the violence, backed down, at least for the time being. The Marquis de Lafayette took up command of the National Guard at Paris. Jean-Sylvain Bailly, president of the Assembly at the time of the Tennis Court Oath, became the city's mayor under a new governmental structure known as the commune. The King visited Paris, where, on 17 July he accepted a tricolore cockade, to cries of Vive la Nation ("Long live the Nation") and Vive le Roi ("Long live the King").[49]

Necker was recalled to power, but his triumph was short-lived. An astute financier but a less astute politician, Necker overplayed his hand by demanding and obtaining a general amnesty, losing much of the people's favour.

As civil authority rapidly deteriorated, with random acts of violence and theft breaking out across the country, members of the nobility, fearing for their safety, fled to neighbouring countries; many of these émigrés, as they were called, funded counter-revolutionary causes within France and urged foreign monarchs to offer military support to a counter-revolution.[50]

By late July, the spirit of popular sovereignty had spread throughout France. In rural areas, many commoners began to form militias and arm themselves against a foreign invasion: some attacked the châteaux of the nobility as part of a general agrarian insurrection known as "la Grande Peur" ("the Great Fear"). In addition, wild rumours and paranoia caused widespread unrest and civil disturbances that contributed to the collapse of law and order.[51]

Abolition of feudalism

On 4 and 11 August 1789 the National Constituent Assembly abolished privileges and feudalism (numerous peasant revolts had almost brought feudalism to an end) in the August Decrees, sweeping away personal serfdom,[52] exclusive hunting rights and other seigneurial rights of the Second Estate (nobility).

Also the tithe (a 10% tax for the Church, gathered by the First Estate (clergy)), which had been the main source of income for many clergymen, was abolished.[53] During the course of a few hours nobles, clergy, towns, provinces, companies and cities lost their special privileges.[54]

Historian Georges Lefebvre summarises the night's work:

"Without debate the Assembly enthusiastically adopted equality of taxation and redemption of all manorial rights except for those involving personal servitude – which were to be abolished without indemnification. Other proposals followed with the same success: the equality of legal punishment, admission of all to public office, abolition of venality in office,[55] conversion of the tithe into payments subject to redemption, freedom of worship, prohibition of plural holding of benefices ... Privileges of provinces and towns were offered as a last sacrifice."[56]

Originally the peasants were supposed to pay for the release of seigneurial dues; these dues affected more than a fourth of the farmland in France and provided most of the income of the large landowners.[57] The majority refused to pay and in 1793 the obligation was cancelled. Thus the peasants got their land free, and also no longer paid the tithe to the church.[58]

Furet emphasises that the decisions of August 1789 survived and became an integral part of

"the founding texts of modern France. They destroyed aristocratic society from top to bottom, along with its structure of dependencies and privileges. For this structure they substituted the modern, autonomous individual, free to do whatever was not prohibited by law ... The Revolution thus distinguished itself quite early by its radical individualism"[59]

The old judicial system, based on the 13 regional parlements, was suspended in November 1789, and officially abolished in September 1790. The main institutional pillars of the old regime had vanished.[60]

Declaration of the Rights of Man

On 26 August 1789 the Assembly published the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which comprised a statement of principles rather than a constitution with legal effect.[61]

The National Constituent Assembly functioned not only as a legislature, but also as a body to draft a new constitution.

Women's March on Versailles

Fuelled by rumours of a reception for the King's bodyguards on 1 October 1789, at which the national cockade had been trampled upon, on 5 October 1789, crowds of women began to assemble at Parisian markets. The women first marched to the Hôtel de Ville, demanding that city officials address their concerns.[62] The women were responding to the harsh economic situations they faced, especially bread shortages. They also demanded an end to royal efforts to block the National Assembly, and for the King and his administration to move to Paris as a sign of good faith in addressing the widespread poverty.

Getting unsatisfactory responses from city officials, as many as 7,000 women joined the march to Versailles, bringing with them cannons and a variety of smaller weapons. Twenty thousand National Guardsmen under the command of Lafayette responded to keep order, and members of the mob stormed the palace, killing several guards.[63] Lafayette ultimately persuaded the king to accede to the demand of the crowd that the monarchy relocate to Paris.

On 6 October 1789, the King and the royal family moved from Versailles to Paris under the "protection" of the National Guards, thus legitimising the National Assembly.

Revolution and the Church

The Revolution caused a massive shift of power from the Roman Catholic Church to the state.[64] Under the Ancien Régime, the Church had been the largest single landowner in the country, owning about 10% of the land in the kingdom.[65] The Church was exempt from paying taxes to the government, while it levied a tithe – a 10% tax on income, often collected in the form of crops – on the general population, only a fraction of which it then redistributed to the poor.[65]

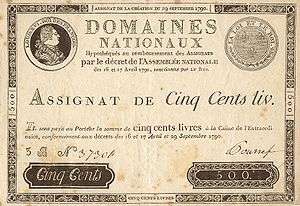

Resentment towards the Church weakened its power during the opening of the Estates General in May 1789. The Church composed the First Estate with 130,000 members of the clergy. When the National Assembly was later created in June 1789 by the Third Estate, the clergy voted to join them, which perpetuated the destruction of the Estates General as a governing body.[66] The National Assembly began to enact social and economic reform. Legislation sanctioned on 4 August 1789 abolished the Church's authority to impose the tithe. In an attempt to address the financial crisis, the Assembly declared, on 2 November 1789, that the property of the Church was "at the disposal of the nation".[67] They used this property to back a new currency, the assignats. Thus, the nation had now also taken on the responsibility of the Church, which included paying the clergy and caring for the poor, the sick and the orphaned.[68] In December, the Assembly began to sell the lands to the highest bidder to raise revenue, effectively decreasing the value of the assignats by 25% in two years.[69] In autumn 1789, legislation abolished monastic vows and on 13 February 1790 all religious orders were dissolved.[70] Monks and nuns were encouraged to return to private life and a small percentage did eventually marry.[71]

The Civil Constitution of the Clergy, passed on 12 July 1790, turned the remaining clergy into employees of the state. This established an election system for parish priests and bishops and set a pay rate for the clergy. Many Catholics objected to the election system because it effectively denied the authority of the Pope in Rome over the French Church. In October a group of 30 bishops wrote a declaration saying they could not accept that law, and this protest also fueled civilian opposition against that law.[53] Eventually, in November 1790, the National Assembly began to require an oath of loyalty to the Civil Constitution from all the members of the clergy.[71] This led to a schism between those clergy who swore the required oath and accepted the new arrangement and those who remained loyal to the Pope. Priests swearing the oath were indicated as 'constitutional', those not taking the oath as 'non-juring' or 'refractory' clergy.[72] Overall, 24% of the clergy nationwide took the oath.[73] This decree stiffened the resistance against the state's interference with the church, especially in the west of France like in Normandy, Brittany and the Vendée, where only a few priests took the oath and the civilian population turned against the revolution.[53]

Widespread refusal led to legislation against the clergy, "forcing them into exile, deporting them forcibly, or executing them as traitors".[69] Pope Pius VI never accepted the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, further isolating the Church in France.

Writing the first constitution

Necker, Mounier, Lally-Tollendal and others argued unsuccessfully for a senate, with members appointed by the crown on the nomination of the people. The bulk of the nobles argued for an aristocratic upper house elected by the nobles. The popular party carried the day: France would have a single, unicameral assembly. The King retained only a "suspensive veto"; he could delay the implementation of a law, but not block it absolutely. The Assembly eventually replaced the historic provinces with 83 départements, uniformly administered and roughly equal in area and population.[60]

Amid the Assembly's preoccupation with constitutional affairs, the financial crisis had continued largely unaddressed, and the deficit had only increased. Honoré Mirabeau now led the move to address this matter, and the Assembly gave Necker complete financial dictatorship.

A new Republican Calendar was established in October 1793, with 10-day weeks that made it very difficult for Catholics to remember Sundays and saints' days. Workers complained it reduced the number of first-day-of-the-week holidays from 52 to 37.[74]

During the Reign of Terror, extreme efforts of dechristianisation ensued, including the imprisonment and massacre of priests and destruction of churches and religious images throughout France. An effort was made to replace the Catholic Church altogether, with civic festivals replacing religious ones. The establishment of the Cult of Reason was the final step of radical dechristianisation. These events led to a widespread disillusionment with the Revolution and to counter-rebellions across France. Locals often resisted de-Christianisation by attacking revolutionary agents and hiding members of the clergy who were being hunted. Eventually, Robespierre and the Committee of Public Safety were forced to denounce the campaign,[75] replacing the Cult of Reason with the deist but still non-Christian Cult of the Supreme Being. The Concordat of 1801 between Napoleon and the Church ended the de-Christianisation period and established the rules for a relationship between the Catholic Church and the French State that lasted until it was abrogated by the Third Republic via the separation of church and state on 11 December 1905. The persecution of the Church led to a counter-revolution known as the Revolt in the Vendée.[76]

Historians Lynn Hunt and Jack Censer argue that some French Protestants, the Huguenots, wanted an anti-Catholic regime, and that Enlightenment thinkers such as Voltaire helped fuel this resentment.[77] The Enlightenment philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, for example, had told French citizens that it was "manifestly contrary to the law of nature... that a handful of people should gorge themselves with superfluities while the hungry multitude goes in want of necessities."[78] Historian John McManners writes, "In eighteenth-century France throne and altar were commonly spoken of as in close alliance; their simultaneous collapse ... would one day provide the final proof of their interdependence."[79]

Intrigues and radicalism

Factions within the Assembly began to clarify. The aristocrat Jacques Antoine Marie de Cazalès and the abbé Jean-Sifrein Maury led what would become known as the right wing, the opposition to revolution (this party sat on the right-hand side of the Assembly). The "Royalist democrats" or monarchiens, allied with Necker, inclined towards organising France along lines similar to the British constitutional model; they included Jean Joseph Mounier, the Comte de Lally-Tollendal, the comte de Clermont-Tonnerre, and Pierre Victor Malouet, comte de Virieu.

The "National Party", representing the centre or centre-left of the assembly, included Honoré Mirabeau, Lafayette, and Bailly; while Adrien Duport, Barnave and Alexandre Lameth represented somewhat more extreme views. Almost alone in his radicalism on the left was the Arras lawyer Maximilien Robespierre, supported by Pétion de Villeneuve and Buzot. Abbé Sieyès led in proposing legislation in this period and successfully forged consensus for some time between the political centre and the left. In Paris, various committees, the mayor, the assembly of representatives, and the individual districts each claimed authority independent of the others. The increasingly middle-class National Guard under Lafayette also slowly emerged as a power in its own right, as did other self-generated assemblies.

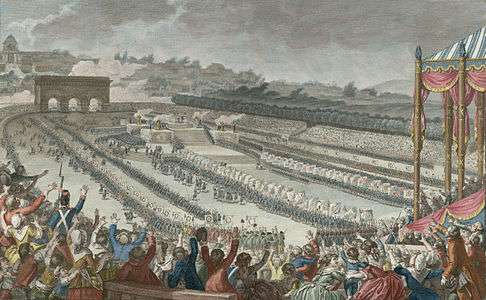

The Assembly abolished the symbolic paraphernalia of the Ancien Régime – armorial bearings, liveries, etc. – which further alienated the more conservative nobles, and added to the ranks of the émigrés. On 14 July 1790, and for several days following, crowds in the Champ de Mars celebrated the anniversary of the fall of the Bastille with the Fête de la Fédération; Talleyrand performed a mass; participants swore an oath of "fidelity to the nation, the law, and the king"; the King and the royal family actively participated.[80]

The electors had originally chosen the members of the Estates-General to serve for a single year. However, by the terms of the Tennis Court Oath, the communes had bound themselves to meet continuously until France had a constitution. Right-wing elements now argued for a new election, but Mirabeau prevailed, asserting that the status of the assembly had fundamentally changed, and that no new election should take place before completing the constitution.[81]

In late 1790 the French army was in considerable disarray. The military officer corps was largely composed of noblemen, who found it increasingly difficult to maintain order within the ranks. In some cases, soldiers (drawn from the lower classes) had turned against their aristocratic commanders and attacked them. At Nancy, General Bouillé successfully put down one such rebellion, only to be accused of being anti-revolutionary for doing so. This and other such incidents spurred a mass desertion as more and more officers defected to other countries, leaving a dearth of experienced leadership within the army.[82]

This period also saw the rise of the political "clubs" in French politics. Foremost among these was the Jacobin Club; 152 members had affiliated with the Jacobins by 10 August 1790. The Jacobin Society began as a broad, general organisation for political debate, but as it grew in members, various factions developed with widely differing views. Several of these factions broke off to form their own clubs, such as the Club of '89.[83]

Meanwhile, the Assembly continued to work on developing a constitution. A new judicial organisation made all magistracies temporary and independent of the throne. The legislators abolished hereditary offices, except for the monarchy itself. Jury trials started for criminal cases. The King would have the unique power to propose war, with the legislature then deciding whether to declare war. The Assembly abolished all internal trade barriers and suppressed guilds, masterships, and workers' organisations: any individual gained the right to practise a trade through the purchase of a license; strikes became illegal.[84]

Royal flight to Varennes

Louis XVI was increasingly dismayed by the direction of the revolution. His brother, the Comte d'Artois and his queen, Marie Antoinette, urged a stronger stance against the revolution and support for the émigrés, while he was resistant to any course that would see him openly side with foreign powers against the Assembly. Eventually, fearing for his own safety and that of his family, he decided to flee Paris to the Austrian border, having been assured of the loyalty of the border garrisons.

Louis cast his lot with General Bouillé, who condemned both the emigration and the Assembly, and promised him refuge and support in his camp at Montmédy. On the night of 20 June 1791 the royal family fled the Tuileries Palace dressed as servants, while their servants dressed as nobles.

However, late the next day, the King was recognised and arrested at Varennes and returned to Paris. The Assembly provisionally suspended the King. He and Queen Marie Antoinette remained held under guard.[85] The King's flight had a profound impact on public opinion, turning popular sentiment further against the clergy and nobility, and built momentum for the institution of a constitutional monarchy.[85]

Completing the constitution

As most of the Assembly still favoured a constitutional monarchy rather than a republic, the various groups reached a compromise which left Louis XVI as little more than a figurehead: he was forced to swear an oath to the constitution, and a decree declared that retracting the oath, heading an army for the purpose of making war upon the nation, or permitting anyone to do so in his name would amount to abdication.

However, Jacques Pierre Brissot drafted a petition, insisting that in the eyes of the nation Louis XVI was deposed since his flight. An immense crowd gathered in the Champ de Mars to sign the petition. Georges Danton and Camille Desmoulins gave fiery speeches. The Assembly called for the municipal authorities to "preserve public order". The National Guard under Lafayette's command confronted the crowd. The soldiers responded to a barrage of stones by firing into the crowd, killing between 13 and 50 people.[86] The incident cost Lafayette and his National Guard much public support.

In the wake of the massacre the authorities closed many of the patriotic clubs, as well as radical newspapers such as Jean-Paul Marat's L'Ami du Peuple. Danton fled to England; Desmoulins and Marat went into hiding.[87]

Meanwhile, in August 1791, a new threat arose from abroad: the King's brother-in-law Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II, King Frederick William II of Prussia, and the King's brother Charles-Philippe, comte d'Artois, issued the Declaration of Pillnitz, declaring their intention to bring the French king in the position "to consolidate the basis of a monarchical government" and that they were preparing their own troops for action,[88] hinting at an invasion of France on the King's behalf.[89]

Although Leopold himself sought to avoid war and made the declaration to satisfy the Comte d'Artois and the other émigrés, the reaction within France was ferocious. The French people expressed no respect for the dictates of foreign monarchs, and the threat of force merely hastened their militarisation.[90]

Even before the Flight to Varennes, the Assembly members had determined to debar themselves from the legislature that would succeed them, the Legislative Assembly. They now gathered the various constitutional laws they had passed into a single constitution, and submitted it to the recently restored Louis XVI, who accepted it, writing "I engage to maintain it at home, to defend it from all attacks from abroad, and to cause its execution by all the means it places at my disposal". The King addressed the Assembly and received enthusiastic applause from members and spectators. With this capstone, the National Constituent Assembly adjourned in a final session on 30 September 1791.[91]

Legislative Assembly (Oct. 1791 – Sept. 1792)

The Legislative Assembly first met on 1 October 1791, elected by those 4 million men – out of a population of 6 million men over the age of 25 – who paid a certain minimum amount of taxes.[92] Under the Constitution of 1791, France would function as a constitutional monarchy. The King had to share power with the elected Legislative Assembly, but he retained his royal veto and the ability to select ministers. Early on, the King vetoed legislation that threatened the émigrés with death and that decreed that every non-juring clergyman must take within eight days the civic oath mandated by the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. Over the course of a year, such disagreements would lead to a constitutional crisis.

Late in 1791, a group of Assembly members who demanded war against Austria and Prussia was, after a remark by the politician Maximilien Robespierre, henceforth known as the 'Girondins', although not all of them really came from the southern province of Gironde. A group around Robespierre – later known as 'Montagnards' or 'Jacobins' – argued against this war; this dispute between the two groups would harden into a bitter enmity over the next year and a half.[88]

In response to the threat of war of August 1791 from Austria and Prussia, leaders of the Assembly saw such a war as a means to strengthen support for their revolutionary government, and the French people as well as the Assembly thought that they would win a war against Austria and Prussia. On 20 April 1792, France declared war on Austria.[88][93] Late April 1792, France invaded and conquered the Austrian Netherlands (roughly present-day Belgium and Luxembourg).[88]

Failure of the constitutional monarchy

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Monarchy |

|---|

.svg.png) |

|

Central concepts |

|

History

|

| Politics portal |

| Part of the Politics series on |

| Republicanism |

|---|

|

Types of republics |

|

History

|

|

Related topics |

| Politics portal |

The Legislative Assembly degenerated into chaos before October 1792. Francis Charles Montague concluded in 1911, "In the attempt to govern, the Assembly failed altogether. It left behind an empty treasury, an undisciplined army and navy, and a people debauched by safe and successful riot."[94]

Lyons argues that the Constituent Assembly had liberal, rational, and individualistic goals that seem to have been largely achieved by 1791. However, it failed to consolidate the gains of the Revolution, which continued with increasing momentum and escalating radicalism until 1794. Lyons identifies six reasons for this escalation. First, the king did not accept the limitations on his powers, and mobilised support from foreign monarchs to reverse it. Second, the effort to overthrow the Roman Catholic Church, sell off its lands, close its monasteries and its charitable operations, and replace it with an unpopular makeshift system caused deep consternation among the pious and the peasants. Third, the economy was badly hurt by the issuance of ever increasing amounts of paper money (assignats), which caused more and more inflation; the rising prices hurt the urban poor who spent most of their income on food. Fourth, the rural peasants demanded liberation from the heavy system of taxes and dues owed to local landowners. Fifth, the working class of Paris and the other cities – the sans-culottes – resented the fact that the property owners and professionals had taken all the spoils of the Revolution. Finally, foreign powers threatened to overthrow the Revolution, which responded with extremism and systematic violence in its own defence.[95]

Constitutional crisis

In the summer of 1792, a large number of Parisians were against the monarchy, and hoped that the Assembly would depose the king, but the Assembly hesitated.[96] At dawn of 10 August 1792, a large, angry crowd of[96] insurgents and popular militias, supported by the revolutionary Paris Commune,[97] marched on the Tuileries Palace where the king resided,[96] assailed the Palace and killed the Swiss Guards who were assigned for the protection of the king.[97]

Around 8:00 am the king decided to leave his palace and seek safety with his wife and children in the Assembly that was gathered in permanent session in Salle du Manège opposite to the Tuileries.[96] The royal family became prisoners.[98] After 11:00 am, a rump session of the Legislative Assembly 'temporarily relieved the king from his task'[96] and thus suspended the monarchy; little more than a third of the deputies were present, almost all of them Jacobins.[98] In reaction, on 19 August the Prussian general Duke of Brunswick invaded France[99] and besieged Longwy.[100]

On 26 August, the Assembly decreed the deportation of refractory priests in the west of France, as "causes of danger to the fatherland", to destinations like French Guiana. In reaction, peasants in the Vendée took over a town, in another step toward civil war.[100] What remained of a national government depended on the support of the insurrectionary Commune. With enemy troops advancing, the Commune looked for potential traitors in Paris.[101][102]

On 2, 3 and 4 September 1792, hundreds of Parisians, supporters of the revolution, infuriated by Verdun being captured by the Prussian enemy, the uprisings in the west of France, and rumours that the incarcerated prisoners in Paris were conspiring with the foreign enemy, raided the Parisian prisons and murdered between 1,000 and 1,500 prisoners, many of them Catholic priests, aristocrats but also common criminals. Jean-Paul Marat, a political ally of Robespierre, in an open letter on 3 September incited the rest of France to follow the Parisian example; Robespierre kept a low profile in regard to the murder orgy.[103] The Assembly and the city council of Paris (la Commune) seemed inept and hardly motivated to call a halt to the unleashed bloodshed.[96]

The Commune sent gangs of National Guardsmen and fédérés into the prisons, and they killed 1,400 or more victims, mostly nonjuring priests. The Commune then sent a circular letter to the other cities of France inviting them to follow this example, and many cities launched their own massacres of prisoners and priests in the "September massacres". The Assembly could offer only feeble resistance. In October, however, there was a counterattack accusing the instigators, especially Marat, of being terrorists. This led to a political contest between the more moderate Girondists and the more radical Montagnards inside the convention, with rumour used as a weapon by both sides. The Girondists lost ground when they seemed too conciliatory. But the pendulum swung again and after Thermidor, the men who had endorsed the massacres were denounced as terrorists.[101][102]

Chaos persisted until the Convention, elected by universal male suffrage and charged with writing a new constitution, met on 20 September 1792 and became the new de facto government of France. The next day it abolished the monarchy and declared a republic. The following day – 22 September 1792, the first morning of the new Republic – was later retroactively adopted as the beginning of Year One of the French Republican Calendar.[104]

French Revolutionary Wars

From May 1792 to June 1815 France was engaged almost continuously (with two short breaks) in wars with Britain and a changing coalition of other major powers. The many French successes led to the spread of the French revolutionary ideals into neighbouring countries, and indeed across much of Europe. However, the final defeat of Napoleon in 1814 (and 1815) brought a reaction that reversed some – but not all – of the revolutionary achievements in France and Europe. The Bourbons were restored to the throne, with the brother of King Louis XVI becoming King Louis XVIII.

The politics of the period inevitably drove France towards war with Austria and its allies. The King, many of the Feuillants, and the Girondins specifically wanted to wage war. The King (and many Feuillants with him) expected war would increase his personal popularity; he also foresaw an opportunity to exploit any defeat: either result would make him stronger. The Girondins wanted to export the Revolution throughout Europe and, by extension, to defend the Revolution within France. The forces opposing war were much weaker. Barnave and his supporters among the Feuillants feared a war they thought France had little chance to win and which they feared might lead to greater radicalisation of the revolution. On the other end of the political spectrum Robespierre opposed a war on two grounds, fearing that it would strengthen the monarchy and military at the expense of the revolution, and that it would incur the anger of ordinary people in Austria and elsewhere. The Austrian emperor Leopold II, brother of Marie Antoinette, may have wished to avoid war, but he died on 1 March 1792.[105] France preemptively declared war on Austria (20 April 1792) and Prussia joined on the Austrian side a few weeks later. The invading Prussian army faced little resistance until it was checked at the Battle of Valmy (20 September 1792) and forced to withdraw.

The new-born Republic followed up on this success with a series of victories in Belgium and the Rhineland in the fall of 1792. The French armies defeated the Austrians at the Battle of Jemappes on 6 November, and had soon taken over most of the Austrian Netherlands. This brought them into conflict with Britain and the Dutch Republic, which wished to preserve the independence of the southern Netherlands from France. After the French king's execution in January 1793, these powers, along with Spain and most other European states, joined the war against France. Almost immediately, French forces suffered defeats on many fronts, and were driven out of their newly conquered territories in the spring of 1793. At the same time, the republican regime was forced to deal with rebellions against its authority in much of western and southern France. But the allies failed to take advantage of French disunity, and by the autumn of 1793 the republican regime had defeated most of the internal rebellions and halted the allied advance into France itself.

This stalemate ended in the summer of 1794 with dramatic French victories. The French defeated the allied army at the Battle of Fleurus, leading to a full Allied withdrawal from the Austrian Netherlands. They pushed the allies to the east bank of the Rhine, allowing France, by the beginning of 1795, to conquer the Dutch Republic itself. The House of Orange was expelled and replaced by the Batavian Republic, a French satellite state. These victories led to the collapse of the anti-French coalition. Prussia, having effectively abandoned the coalition in the fall of 1794, made peace with revolutionary France at Basel in April 1795, and soon thereafter Spain also made peace with France. Britain and Austria were the only major powers to remain at war with France.

Colonial uprisings

Although the French Revolution had a dramatic impact in numerous areas of Europe, the French colonies felt a particular influence. As the Martinican author Aimé Césaire put it, "there was in each French colony a specific revolution, that occurred on the occasion of the French Revolution, in tune with it."[106]

The Haitian Revolution (Saint Domingue) became a central example of slave uprisings in French colonies. In the 1780s, Saint-Domingue had been France's wealthiest colony, producing more sugar than all the British West Indies colonies put together. During the Revolution, the National Convention voted to abolish slavery in February 1794, months after the rebelling slaves had already announced an abolition of slavery in Saint-Domingue.[107] However, the 1794 decree was only implemented in Saint-Domingue, Guadeloupe and Guyane, and was a dead letter in Senegal, Mauritius, Réunion and Martinique, the last of which had been conquered by the British, who maintained the institution of slavery on that Caribbean island.[108]

First Republic

National Convention (Sept. 1792–95)

Late in August/early September 1792, elections were held, now under universal male suffrage, for the new National Convention,[103] which replaced the Legislative Assembly on 20 September 1792. From the start the Convention suffered from the bitter division between a group (political faction) around Robespierre, Danton and Marat, referred to as 'Montagnards' or the 'extreme left', and a group around Brissot, referred to as 'Girondins' as moderate republicans. But the majority of the representatives, referred to as 'la Plaine', were member of neither of those two antagonistic groups and managed to preserve some speed in the convention's debates;[103][109] The Plain was formed by independents (as Barère, Cambon and Carnot) but dominated by the radical Mountain.[110] The Plaine occupied the middle only in the sense that its votes determined which group of revolutionary leaders should enjoy the sanctions of relative legality.[111] Immediately on 21 September the Convention abolished the monarchy, making France the French First Republic. A new French Republican Calendar was introduced on 24 October 1793 to replace the Christian Gregorian calendar, renaming the year 1792 as year 1 of the Republic.[52]

With wars against Prussia and Austria having started earlier in 1792, France also declared war on the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Dutch Republic in February 1793. In the course of 1793, the Holy Roman Empire, the kings of Spain, Portugal and Naples and the Grand-Duke of Tuscany declared war against France.[112]

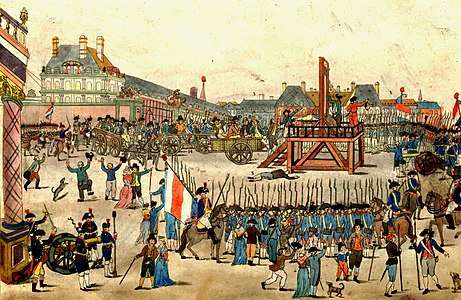

Execution of Louis XVI

In the Brunswick Manifesto, the Imperial and Prussian armies threatened retaliation on the French population if it were to resist their advance or the reinstatement of the monarchy. This among other things made Louis appear to be conspiring with the enemies of France. On 17 January 1793 Louis was condemned to death for "conspiracy against the public liberty and the general safety" by a close majority in Convention: 361 voted to execute the king, 288 voted against, and another 72 voted to execute him subject to a variety of delaying conditions. The former Louis XVI, now simply named Citoyen Louis Capet (Citizen Louis Capet) was executed by guillotine on 21 January 1793 on the Place de la Révolution, former Place Louis XV, now called the Place de la Concorde.[113] Conservatives across Europe were horrified and monarchies called for war against revolutionary France.[114][115]

Economy

When prices rose in February the sans-culottes – poor labourers and craftsmen – rioted; the Girondins were held responsible. On 24 February the Convention decreed the first, but unsuccessful Levée en Masse as the attempt to draft new troops set off an uprising in rural France. The Montagnards lost influence in Marseille, Toulon and Lyon. This encouraged the Jacobins to seize power through a parliamentary coup, backed up by force effected by mobilising public support against the Girondin faction, and by utilising the mob power of the Parisian sans-culottes. An alliance of Jacobin and sans-culottes elements thus became the effective center of the new government. Policy became considerably more radical, as "The Law of the Maximum" set food prices and led to executions of offenders.[116]

The price control policy was coeval with the rise to power of the Committee of Public Safety and the Reign of Terror. The Committee first attempted to set the price for only a limited number of grain products, but by September 1793 it expanded the "maximum" to cover all foodstuffs and a long list of other goods.[117] Widespread shortages and famine ensued. The Committee reacted by sending a small revolutionary army into the countryside to arrest farmers and seize crops. This temporarily solved the problem in Paris, but the rest of the country suffered. By the spring of 1794, forced collection of food was not sufficient to feed even Paris, and the days of the committee were numbered. When Robespierre was sent to the guillotine in July 1794, the crowd jeered, "There goes the dirty maximum!"[118]

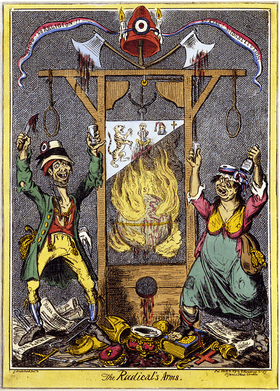

Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror, or more commonly The Terror (French: la Terreur), refers to a period of the French Revolution when numerous public executions took place in response to revolutionary fervour, anti-clerical, anti-federalist and anti-aristocratic sentiment, and spurious accusations of treason by Maximilien Robespierre and the Committee of Public Safety. There is disagreement among historians over when exactly “the Terror” started, either in June 1793 or September 1793.

In July the Committee of Public Safety came under the control of Maximilien Robespierre, and the Jacobins unleashed the Reign of Terror (1793–94). According to archival records, at least 16,594 people died under the guillotine or otherwise after accusations of counter-revolutionary activities.[119] As many as 40,000 accused prisoners may have been summarily executed without trial or died awaiting trial.[119][120]

On 2 June 1793, Paris sections – encouraged by the enragés ("enraged ones") Jacques Roux and Jacques Hébert – took over the Convention, calling for administrative and political purges, a low fixed price for bread, and a limitation of the electoral franchise to sans-culottes alone.[121] With the backing of the National Guard, they managed to persuade the convention to arrest ten members of the Commission of Twelve and 21 Girondin leaders, including Jacques Pierre Brissot. Following these arrests, the Jacobins gained control of the Committee of Public Safety on 10 June, installing the revolutionary dictatorship.[122]

On 24 June, the Convention adopted the first republican constitution of France, variously referred to as the French Constitution of 1793 or Constitution of the Year I. It was progressive and radical in several respects, in particular by establishing universal male suffrage. It was ratified by public referendum, but normal legal processes were suspended before it could take effect.[123]

On 13 July, the assassination of Jean-Paul Marat – a Jacobin leader and journalist known for his bloodthirsty rhetoric – by Charlotte Corday, a Girondin, resulted in further increase of Jacobin political influence. Georges Danton was removed from the Committee and Robespierre, "the Incorruptible", became its most influential member as it moved to take radical measures against the Revolution's domestic and foreign enemies.[122]

The Reign of Terror ultimately weakened the revolutionary government, while temporarily ending internal opposition. The Jacobins expanded the size of the army, and Carnot replaced many aristocratic officers with soldiers who had demonstrated their patriotism, if not their ability. The Republican army repulsed the Austrians, Prussians, British, and Spanish. At the end of 1793, the army began to prevail and revolts were defeated with ease. The Ventôse Decrees (February–March 1794) proposed the confiscation of the goods of exiles and opponents of the Revolution, and their redistribution to the needy. However, this policy was never fully implemented.[124]

Three approaches attempt to explain the Reign of Terror imposed by the Jacobins in 1793–94. The older Marxist interpretation argued the Terror was a necessary response to outside threats (in terms of other countries going to war with France) and internal threats (of traitors inside France threatening to frustrate the Revolution). In this interpretation, as expressed by the Marxist historian Albert Soboul, Robespierre and the sans-culottes were heroes for defending the revolution from its enemies. François Furet has argued that foreign threats had little to do with the terror.[125] Instead, the extreme violence was an inherent part of the intense ideological commitment of the revolutionaries – their Utopian goals required exterminating opposition. Soboul's Marxist interpretation has been largely abandoned by most historians since the 1990s. Hanson (2009) takes a middle position, recognising the importance of the foreign enemies, and sees the terror as a contingency that was caused by the interaction of a series of complex events and the foreign threat. Hanson says the terror was not inherent in the ideology of the Revolution, but that circumstances made it necessary.[126] Scholars have argued that the violence in the revolution served a sacrificial function.[127]

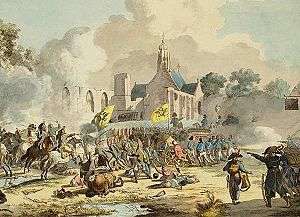

Internal and external wars

Introduction of a nationwide conscription for the army in February 1793 was the spark that in March made the Vendée, already rebellious since 1790 because of the changes imposed on the Roman Catholic Church by the Civil Constitution of the Clergy (1790),[128] ignite into civil (guerrilla) war against the French Revolutionary government in Paris.[109][129][130][131]

North of the Loire, similar revolts were started by the so-called Chouans (royalist rebels).[132] In March 1793, France also declared war on Spain, the Vendée rebels won some victories against Paris, and the French army was defeated in Belgium by Austria with the French general Dumouriez defecting to the Austrians: the French Republic's survival was now in real danger.[109] Facing local revolts and foreign invasions in both the East and West of the country, the most urgent government business was the war.[133] On 6 April 1793, to prevent the Convention from losing itself in abstract debate and to streamline government decisions, the Comité de salut public (Committee of Public Prosperity) was created, as executive government which was accountable to the convention.[109]

Girondins expelled

In April 1793, the Girondins indicted Jean-Paul Marat before the Revolutionary Tribunal for 'attempting to destroy the sovereignty of the people' and 'preaching plunder and massacre', referring to his behaviour during the September massacres. Marat was quickly acquitted but the incident further exacerbated the 'Girondins' versus 'Montagnards' party strife in the convention.[109]

Jacques Hébert, Convention member leaning to the 'Cordeliers' group, on 24 May 1793 called on the sans-culottes to rise in revolt against the "henchmen of Capet [the ex-king] and Dumouriez [the defected general]". Hébert was arrested by a Convention committee. While that committee consisted only of members from The Plain and the Girondins, the anger of the sans-culottes was directed towards the Girondins. 25 May, a delegation of la Commune (the Paris city council) protested against Hébert's arrest. The convention's President Isnard, a Girondin, answered them: "Members of la Commune [...] If by your incessant rebellions something befalls to the representatives of the nation, I declare, in the name of France, that Paris will be totally obliterated".[109]

On 2 June 1793, the convention's session in Tuileries Palace degenerated into chaos and pandemonium. Crowds of people swarmed in and around the palace. Incessant screaming from the public galleries suggested that all of Paris was against the Girondins. Petitions circulated, indicting and condemning 22 Girondins. Barère, member of the Comité de salut public, suggested: to end this division which is harming the Republic, the Girondin leaders should lay down their offices voluntarily. Late that night after much more tumultuous debate, dozens of Girondins had resigned and left the convention.[109]

Abounding civil war

By the summer of 1793, most French departments in one way or another opposed the central Paris government. Girondins who fled from Paris after 2 June led those revolts.[134] In Brittany's countryside, the people rejecting the Civil Constitution of the Clergy of 1790 had taken to a guerrilla warfare known as Chouannerie.[128] But generally, the French opposition against 'Paris' had now evolved into a plain struggle for power over the country[134] against the 'Montagnards' around Robespierre and Marat now dominating Paris.[128]

In June–July 1793, Bordeaux, Lyon, Toulon, Marseilles, Caen, Brittany and the rest of Normandy gathered armies to march on Paris and against 'the revolution'.[129][128] In July, the deposed 'Montagnard' head of the Lyon city council was guillotined.[128] On 1 August Barère incited the convention to tougher measures against the Vendée, at war with Paris since March: "We'll have peace only when no Vendée remains [...] we'll have to exterminate that rebellious people".[129] In August, Convention troops besieged Lyon.[128] On 17 August 1793, the Convention voted for general conscription, a second levée en masse, which mobilised all citizens to serve as soldiers or suppliers in the war effort.[133] By August, political disagreement seemed enough to be summoned before the Tribunal; appeal against a Tribunal verdict was impossible.[128] Late August 1793, Adam Philippe Custine an army general had been guillotined on the accusation of choosing too timid strategies on the battlefield.[128]

Early September 1793, militants urged the convention to do more to quell the counter-revolution. A delegation of the Commune (Paris city council) suggested to form revolutionary armies to arrest hoarders and conspirators.[128] Barère, on 5 September reacted favorably, saying: let's "make terror the order of the day!"[128] Criteria for bringing someone before the Revolutionary Tribunal had always been vast and vague.[134] On 9 September The National Convention voted to establish sans-culottes paramilitary forces, revolutionary armies, and to force farmers to surrender grain demanded by the government.[133] On 17 September, the Law of Suspects was passed, which ordered the arrest of suspected counter-revolutionaries and people who had revealed themselves as "enemies of freedom".[135] This decree was one of the causes for some 17,000 legal death sentences until the end of July 1794, an average of 370 per week – reason for historians to label those 101/2 months 'the (Reign of) Terror'.[136][137] On 19 September the Vendée rebels again defeated a Republican Convention army.[129] On 29 September, the Convention extended price limits from grain and bread to other household goods and established the Law of the Maximum, intended to prevent price gouging and supply food to the cities.[133]

On 1 October Barère repeated his plea to subdue the Vendée: "refuge of fanaticism, where priests have raised their altars".[129] On 9 October the Convention troops captured Lyon and reinstated a Montagnard government there.[128] On 10 October the Convention decreed to recognize the Committee of Public Safety as the supreme "Revolutionary Government",[138] (which was consolidated on 4 December).[139] The provisional government would be revolutionary until peace according to Saint-Just. Though the French Constitution of 1793 was overwhelmingly popular and its drafting and ratification buoyed popular support for the Montagnards, the Convention set it aside indefinitely until a future peace.[140] Mid-October, the widowed former queen Marie Antoinette was on trial for a long list of charges such as "teaching [her husband] Louis Capet the art of dissimulation" and incest with her son, she too was guillotined.[128] At the end of October 1793, 21 former 'Girondins' Convention members who hadn't left Paris after June were convicted to death and executed, on the charge of federalism, verbally supporting the preparation of an insurrection in Caen by fellow-Girondins.[128]

Suppressing and retaliating the revolts

17 October 1793, the 'blue' Republican army near Cholet defeated the 'white' Vendéan insubordinate army and all surviving Vendée residents, counting in tens of thousands, fled over the river Loire north into Brittany.[129] A Convention's representative on mission in Nantes commissioned in October to pacify the region did so by simply drowning prisoners in the river Loire: until February 1794 he drowned at least 4,000.[134]

Meanwhile, the instalment of the Republican Calendar on 24 October 1793 caused an anti-clerical uprising. Hébert's and Chaumette's atheist movement campaigned to dechristianise society. The climax was reached with the celebration of the flame of Reason in Notre Dame Cathedral on 10 November.[141]

By November 1793, the revolts in Normandy, Bordeaux and Lyon were overcome, in December also that in Toulon.[128] Two representatives on mission sent to punish Lyon between November 1793 and April 1794 executed 2,000 people to death by guillotine or firing-squad.[134] The Vendéan army since October roaming through Brittany on 12 December 1793 again ran up against Republican troops and saw 10,000 of its rebels perish, meaning the end of this once threatening army.[134]

Some historians claim that after that Vendéan defeat Convention Republic armies in 1794 massacred 117,000 Vendéan civilians to obliterate the Vendéan people, but others contest that claim.[142] Some historians consider the total civil war to have lasted until 1796 with a toll of 170,000[143] or 450,000 lives.[144][145]

Because of the extremely brutal forms that the Republican repression took in many places, historians such as Reynald Secher have called the event a "genocide".[146][147][148] Historian François Furet concluded that the repression in the Vendee "not only revealed massacre and destruction on an unprecedented scale but also a zeal so violent that it has bestowed as its legacy much of the region's identity."[149]

Profuse executions

The guillotine became the tool for a string of executions. Louis XVI had already been guillotined before the start of the terror; Queen Marie Antoinette, Barnave, Bailly, Brissot and other leading Girondins, Philippe Égalité (despite his vote for the death of the King), Madame Roland and many others were executed by guillotine. The Revolutionary Tribunal summarily condemned thousands of people to death by the guillotine, while mobs beat other victims to death.

At the peak of the terror, the slightest hint of counter-revolutionary thoughts or activities (or, as in the case of Jacques Hébert, revolutionary zeal exceeding that of those in power) could place one under suspicion, and trials did not always proceed according to contemporary standards of due process. Sometimes people died for their political opinions or actions, but many for little reason beyond mere suspicion, or because some others had a stake in getting rid of them. Most of the victims received an unceremonious trip to the guillotine in an open wooden cart (the tumbrel). In the rebellious provinces, the government representatives had unlimited authority and some engaged in extreme repressions and abuses. For example, Jean-Baptiste Carrier became notorious for the Noyades ("drownings") he organised in Nantes;[150] his conduct was judged unacceptable even by the Jacobin government and he was recalled.[151]

Guillotining politicians

Maximilien Robespierre, since July 1793 member of the Committee of Public Prosperity,[129] on 5 February 1794 in a speech in the Convention identified Jacques Hébert and his faction as "internal enemies" working toward the triumph of tyranny.[134] After a dubious trial Hébert and some allies, charged with counter-revolutionary activities,[152] were guillotined in March.[134]

On 5 April, again at the instigation of Robespierre, Danton, a moderate Montagnard, and 13 associated politicians, charged with counter-revolutionary activities,[152] were executed.[134] A week later again 19 politicians. This hushed the Convention deputies: if henceforth they disagreed with Robespierre they hardly dared to speak out.[134] On 22 April three politicians were taken to the scaffold: Malesherbes and the deputés Isaac René Guy le Chapelier and Jacques Guillaume Thouret, four times elected president of the Constituent Assembly.

On 7 June 1794, Robespierre advocated a new state religion and recommended the Convention acknowledge the existence of the "Supreme Being".[152] A law enacted on 10 June 1794 (22 Prairial II) further streamlined criminal procedures: if the Revolutionary Tribunal saw sufficient proof of someone being an "enemy of the people" a counsel for defence would not be allowed. The frequency of guillotine executions in Paris now rose from on average three a day to an average of 29 a day.[134]

Meanwhile, France's external wars were going well, with victories over Austrian and British troops in May and June 1794 opening up Belgium for French conquest.[134] But cooperation within the Committee of Public Prosperity, since April 1793 the de facto executive government, started to break down. On 29 June 1794, three colleagues of Robespierre at 'the Committee' called him a dictator in his face – Robespierre baffled left the meeting. This encouraged other Convention members to also defy Robespierre. On 26 July, a long and vague speech of Robespierre wasn't met with thunderous applause as usual but with hostility; some deputies yelled that Robespierre should have the courage to say which deputies he deemed necessary to be killed next, what Robespierre refused to do.[134]

In the Convention session of 27 July 1794 (9 Thermidor of Year II), Robespierre and his allies hardly managed to say a word as they were constantly interrupted by a row of critics such as Tallien, Billaud-Varenne, Vadier, Barère and acting president Thuriot. Finally, even Robespierre's own voice failed on him: it faltered at his last attempt to beg permission to speak.[134]

A decree was adopted to arrest Robespierre, Saint-Just and Couthon. 28 July, they and 19 other leading Jacobins were beheaded. 29 July, again 70 members of the Parisian Commune were guillotined.[134]

Subsequently, the Law of 22 Prairial (10 June 1794) was repealed, and the 'Girondins' expelled from the Convention in June 1793, if not dead yet, were reinstated as Convention deputies.[153] In November the Jacobin Club was closed and banned.[154][155]

Disregarding the lower classes

After July 1794, the French government was dominated by 'Girondins', who indulged in revenge and violence and death sentences against people associated with the previous 'Jacobin'/'Montagnard' governments around Robespierre and Marat, in what was known as the White Terror.[156]

After July 1794, most civilians henceforth ignored the Republican calendar and returned to the traditional seven-day weeks. The government in a law of 21 February 1795 set steps of return to freedom of religion and reconciliation with the since 1790 refractory Catholic priests, but any religious signs outside churches or private homes, such as crosses, clerical garb, bell ringing, remained prohibited. When the people's enthusiasm for attending church grew to unexpected levels the government backed out and in October 1795 again, like in 1790, required all priests to swear oaths on the Republic.[153]

In the very cold winter of 1794–95, the French army was demanding more and more bread. It was getting scarce in Paris, as was wood to keep houses warm. As a result, in an echo of the October 1789 March on Versailles, on 1 April 1795 (12 Germinal III) a mostly female crowd marched on the Convention calling for bread. But no Convention member sympathized, and they told the women to return home. Again in May, a crowd of 20,000 men and 40,000 women invaded the convention and killed a deputy in the halls, but again they failed to make the Convention take notice of the needs of the lower classes. Instead, the Convention banned women from all political assemblies, and deputies who had stood with this insurrection were sentenced to death: such allegiance between parliament and street fighting was no longer tolerated.[153]

Late 1794, France conquered present-day Belgium.[157] In January 1795 they subdued the Dutch Republic with full consent and cooperation of the influential Dutch patriottenbeweging ('patriots movement'), resulting in the Batavian Republic, a satellite and puppet state of France.[158][159] In April 1795, France concluded a peace agreement with Prussia,[160] later that year peace was agreed with Spain.

The Directory (1795–99)