Second Council of Lyon

The Second Council of Lyon was the fourteenth ecumenical council of the Catholic Church, convoked on 31 March 1272 and convened in Lyon, Kingdom of Arles (in modern France), in 1274.[1] Pope Gregory X presided over the council, called to act on a pledge by Byzantine emperor Michael VIII to reunite the Eastern church with the West.[2] The council was attended by about 300 bishops, 60 abbots[3] and more than a thousand prelates or their procurators, among whom were the representatives of the universities. Due to the great number of attendees, those who had come to Lyon without being specifically summoned were given "leave to depart with the blessing of God" and of the Pope. Among others who attended the council were James I of Aragon, the ambassador of the Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos with members of the Greek clergy and the ambassadors of Abaqa Khan of the Ilkhanate. Thomas Aquinas had been summoned to the council, but died en route at Fossanova Abbey. Bonaventure was present at the first four sessions, but died at Lyon on 15 July 1274. As at the First Council of Lyon, Thomas Cantilupe was an English attender and a papal chaplain.[4]

- The First Council of Lyon, the Thirteenth Ecumenical Council, took place in 1245.

| Second Council of Lyon | |

|---|---|

| Date | 1272–1274 |

| Accepted by | Catholic Church |

Previous council | First Council of Lyon |

Next council | Council of Vienne |

| Convoked by | Pope Gregory X |

| President | Pope Gregory X |

| Attendance | 560 (bishops and abbots) |

| Topics | Conquest of the Holy Land, Great Schism, filioque, conclaves |

Documents and statements | Approval of Dominicans and Franciscans, apparent resolution of the Great Schism, tithe for the crusade, internal reforms |

| Chronological list of ecumenical councils | |

| Part of a series on |

| Ecumenical councils of the Catholic Church |

|---|

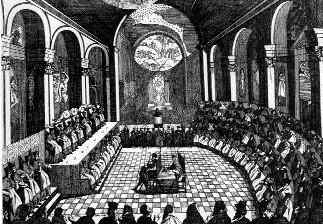

Renaissance depiction of the Council of Trent |

| Antiquity (c. 50 – 451) |

| Early Middle Ages (553–870) |

| High and Late Middle Ages (1122–1517) |

| Modernity (1545–1965) |

|

|

In addition to Aragon, which James represented in person, representatives of the kings of Germany, England, Scotland, France, the Spains and Sicily[5] were present, with procurators also representing the kingdoms of Norway, Sweden, Hungary, Bohemia, the "realm of Dacia" and the duchy of Poland. In the procedures to be observed in the council, for the first time the nations appeared as represented elements in an ecclesiastical council, as they had already become represented in the governing of medieval universities. This innovation marks a stepping-stone towards the acknowledgment of coherent ideas of nationhood, which were in the process of creating the European nation-states.

The main topics discussed at the council were the conquest of the Holy Land and the union of the Eastern and Western Churches. The first session took place on 7 May 1274 and was followed by five additional sessions on 18 May 1274, 4 or 7 June 1274, 6 July 1274, 16 July 1274, and 17 July 1274. By the end of the council, 31 constitutions were promulgated. In the second session, the fathers approved the decree Zelus fidei, which contained no juridical statutes but rather summed up constitutions about the perils of the Holy Land, the means for paying for a proposed crusade, the excommunication of pirates and corsairs and those who protected them or traded with them, a declaration of peace among Christians, a grant of an indulgence for those willing to go on crusade, restoration of communion with the Greeks, and the definition of the order and procedure to be observed in the council. The Greeks conceded on the issue of the Filioque (two words added to the Nicene Creed), and union was proclaimed, but the union was later repudiated by Andronicus II,[2] heir to Michael VIII. The council also recognized Rudolf I as Holy Roman Emperor, ending the interregnum.[2]

Union of the Churches

Wishing to end the Great Schism that divided the Catholic Church from Eastern Orthodoxy, Pope Gregory X sent an embassy to Michael VIII, who had reconquered Constantinople, putting an end to the remnants of the Latin Empire in the East, and he asked Latin despots in the East to curb their ambitions. Eastern dignitaries arrived at Lyon on 24 June 1274 presenting a letter from the Emperor. On 29 June 1274 (the Feast of Peter and Paul, patronal feast of the popes), Gregory celebrated Mass in St John's Church where both sides took part. The Greeks read the Nicene Creed, with the Western addition of the Filioque clause sung three times. The council was seemingly a success, but did not provide a lasting solution to the schism; the Emperor was anxious to heal the schism, but the Eastern clergy opposed the decisions of the Council. Patriarch Joseph of Constantinople abdicated, and was replaced by John Bekkos, a convert to the cause of union. In spite of a sustained campaign by Bekkos to defend the union intellectually, and vigorous and brutal repression of opponents by Michael, the vast majority of Byzantine Christians remained implacably opposed to union with the Latin "heretics". Michael's death in December 1282 put an end to the union of Lyons. His son and successor Andronicus II repudiated the union in the Council of Blachernae (1285), and Bekkos was forced to abdicate, being eventually exiled and imprisoned under house arrest until his death in 1297.

Plans for a Crusade

The council drew up plans for a crusade to recover the Holy Land, which was to be financed by a tithe imposed for 6 years on all the benefices of Christendom. The plans were approved but nothing concrete was done.[6] James I of Aragon wished to organize the expedition at once, but this was opposed by the Knights Templar.[7]

Ambassadors of the Khan of the Tatars negotiated with the Pope, who asked them to leave Christians in peace during their war against Islam.[7] The Mongol leader Abaqa Khan sent a delegation of 13[8]-16 Mongols to the Council, which created a great stir, particularly when their leader underwent a public baptism. Among the embassy were David of Ashby, and the clerk Rychaldus.[9] According to one chronicler, "The Mongols came, not because of the Faith, but to conclude an alliance with the Christians".[10]

Abaqa's Latin secretary Rychaldus delivered a report to the Council, which outlined previous European-Ilkhanid relations under Abaqa's father, Hulagu, where after welcoming the Christian ambassadors to his court, Hulagu had agreed to exempt Latin Christians from taxes and charges, in exchange for their prayers for the Qaghan. According to Richardus, Hulagu had also prohibited the molestation of Frank establishments, and had committed to return Jerusalem to the Franks.[11] Richardus told the assembly that even after Hulagu's death, Abaqa was still determined to drive the Mamluks from Syria.[12]

At the Council, Pope Gregory promulgated a new Crusade to start in 1278 in liaison with the Mongols.[13] The Pope put in place a vast program to launch the Crusade, which was written down in his “Constitutions for the zeal of the faith”. This text puts forward four main decisions to accomplish the Crusade: the imposition of a new tax during three years, the interdiction of any kind of trade with the Saracens, the supply of ships by the Italian maritime Republics, and the alliance of the West with Byzantium and the Il-Khan Abagha.[14] However, despite papal plans, there was little support from European monarchs, who at this point were more likely to give lip service to the idea of a Crusade than to commit actual troops. The Pope's death in 1276 put an end to any such plans, and the money that had been gathered was instead distributed in Italy.

Other topics debated

The council dealt with the reform of the Church, regarding which Gregory had sent out inquiries. Several bishops and abbots were deposed for unworthiness, and some mendicant orders were suppressed. On the other hand, the two new orders of Dominicans and Franciscans were approved.

There had been several lengthy vacancies of the Holy See, most recently the sede vacante that had lasted from the death of Clement IV, 29 November 1268, until Gregory's election, 1 September 1271. The council decided that in future the cardinals should not leave the conclave until they had elected a pope. This decision was suspended in 1276 by Pope Adrian V, and then revoked by Pope John XXI. It has since been re-established, and is the basis of present legislation on papal elections.

Lyon II was the first council to define the doctrine of Purgatory.[15]

Finally, the council dealt with the Imperial throne, which Alfonso X of Castile claimed. His claim was disallowed by the Pope, and Rudolph I was proclaimed King of the Romans and future emperor on 6 June 1274.

See also

Notes

- "Gregory X convoked the general council on 31 March 1272...outlined three themes: union with the Greeks, the crusade, and the reform of the church. Regarding the third theme, which was not only traditional in medieval councils but was also required by the actual state of ecclesiastical morals, the pope in March 1273 sought the opinion of all christian people and asked for their help. After long preparatory arrangements the council assembled at Lyons and opened on 7 May 1274...The Greeks arrived late, on 24 June 1274, since they had been shipwrecked...The council had 6 general sessions: on 7 May 1274, 18 May 1274, 4 or 7 June 1274, 6 July 1274, 16 July 1274, and 17 July 1274. (from Papal Encyclicals.net, accessed 23 January 2012

- Wetterau, Bruce. World history. New York: Henry Holt and company. 1994

- Papal Encyclicals.net

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- The Sicilian representation was that sent by Charles of Anjou, whom the Papacy had placed on the throne of Sicily in 1266, to the detriment of Aragonese claims. The uprising in Aragon's favour called the Sicilian Vespers would take place 30 March 1282.

- Second Council of Lyons – 1274

- Georges Goyau, "Second Council of Lyons (1274)" in Catholic Encyclopedia

- Richard, p. 439/English

- Richard, "Histoire des Croisades", p.452

- Quoted in Jean Richard, p.452

- Jean Richard, p.435/French

- Jackson, pp. 167–168

- "1274: Promulgation of a Crusade, in liaison with the Mongols", Jean Richard, "Histoire des Croisades", p.502/French, p. 487/English

- ”Le Pape Grégoire X s’efforce alors de mettre sur pied un vaste programme d’aide à la Terre Sainte, les “Constitutions pour le zèle de la foi”, qui sont acceptées au Concile de Lyon de 1274. Ce texte prévoit la levée d’une dime pendant trois ans pour la croisade, l’interdiction de tout commerce avec les Sarasins, la fourniture de bateaux par les républiques maritimes italiennes, et une alliance de l’Occident avec Byzance et l’Il-Khan Abagha" (Michel Balard, Les Latins en Orient (XIe–XVe siècle), p.210.

- Council of Lyons II (1274):DS 856

References

- Mansi, Giovan Domenico; Philippe Labbe; Jean Baptiste Martin (1780). Sacrorum conciliorum nova et amplissima collectio. Tomus 24. Venice: Antonius Zatta. pp. 37–134. [in Latin]

- von Hefele, Karl Joseph (1867). Conciliengeschichte, nach den Quellen, bearb. von C.J. Hefele (fortgesetzt von J. Cardinal Hergenröther). Volume 6. Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder.

- Gatto, Ludovico (1959). Il pontificato di Gregorio X: 1271-1276. Studi Storici, 28-30. Rome: Istituto storico Italiano per il Medioevo. ISBN 978-88-495-1499-5.

- Nicol, Donald MacGillivray (1971). The Byzantine Reaction to the Second Council of Lyons, 1274. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hughes, Philip (1979). History of the Church: Volume 3: The Revolt Against The Church: Aquinas To Luther. London: Sheed & Ward. pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-0-7220-7983-6.

- Tanner, Norman; Alberigo, Giuseppe (1990). Decrees of the Ecumenical Councils: Nicaea I to Lateran V. London: Sheed & Ward. ISBN 978-0-87840-490-2.

- Richard, Jean (1999). The Crusades: c. 1071–c. 1291. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-62566-1.

- Jackson, Peter (2005). The Mongols and the West, 1221–1410. Longman. ISBN 0-582-36896-0.

- Baldwin, Philip B. (2014). Pope Gregory X and the Crusades. Woodbridge, Suffolk UK: Boydell & Brewer Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84383-916-3.

External links

- Catholic Encyclopedia: "Lyon, Second Council of"

- Norman P. Tanner, editor Decrees of the Ecumenical Councils, Second Council of Lyon: Zelus fidei and the conciliar constitutions, including the three post-conciliar constitutions

- Second Council of Lyon