Treaty of Amiens

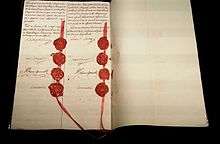

The Treaty of Amiens (French: la paix d'Amiens) temporarily ended hostilities between France and Great Britain during the French Revolutionary Wars. It marked the end of the French Revolutionary Wars; after a short peace it set the stage for the Napoleonic Wars. Britain gave up most of its recent conquests; France was to evacuate Naples and Egypt. Britain retained Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and Trinidad. It was signed in the city of Amiens on 27 March 1802 (4 Germinal X in the French Revolutionary calendar) by Joseph Bonaparte and Marquess Cornwallis as a "Definitive Treaty of Peace." The consequent peace lasted only one year (18 May 1803) and was the only period of general peace in Europe between 1793 and 1814.

Long name:

| |

|---|---|

James Gillray, The first Kiss this Ten Years! —or—the meeting of Britannia & Citizen François (1803) | |

| Type | Peace treaty |

| Signed | 27 March 1802 |

| Location | Amiens, France |

| Effective | 27 March 1802 |

| Expiration | 18 May 1803 |

| Signatories | Joseph Bonaparte for the French Republic Marquess Cornwallis for Britain José Nicolás de Azara for the Kingdom of Spain Rutger Jan Schimmelpenninck for the Batavian Republic |

| Language | English, French |

Under the treaty, Britain recognised the French Republic. Together with the Treaty of Lunéville (1801), the Treaty of Amiens marked the end of the Second Coalition, which had waged war against Revolutionary France since 1798.

National goals

Great Britain wanted the peace to rebuild economically especially by restoration of trade with continental Europe. It also wanted to end its isolation from other powers, and achieved that goal by a rapprochement with Russia that provided the momentum to agree to the treaty with France. Amiens also mollified the antiwar Whig opposition in Parliament.[1]

Napoleon used the interlude for major internal reforms such as the promulgation of the new legal system under the Code Napoleon, making peace with the Vatican by the Concordat, and issuing a new constitution that gave him lifetime control. France made territorial gains in Switzerland and Italy. However Napoleon's goal of a North American Empire collapsed with the failure of his army in Haiti, so he gave it up and sold Louisiana to the United States.[2]

The administration of President Thomas Jefferson used British banks to fund the purchase of Louisiana, reduced the American military budget, and partly dismantled the Hamiltonian financial program. However, the French colonies in the West Indies no longer needed to use American ships to move their products to Europe. Although the terms of the Treaty did not favour his country, British Prime Minister Henry Addington skillfully used the interlude to rebuild British strength, so that when fighting renewed in spring 1803, the Royal Navy quickly gained control of the seas.[3] However the foreign policy of the United States, which was hostile to both Britain and France, and strongly opposed by the Federalist minority in Congress, came under heavy pressure from all sides.[4]

Early diplomacy

The War of the Second Coalition started well for the coalition, with successes in Egypt, Italy and Germany. The successes proved to be short-lived, however; after France's victories at the Battles of Marengo and Hohenlinden, Austria, Russia and Naples sued for peace, with Austria eventually signing the Treaty of Lunéville. Horatio Nelson's victory at the Battle of Copenhagen on 2 April 1801 halted the creation of the League of Armed Neutrality and led to a negotiated ceasefire.[5]

The French First Consul, Napoleon Bonaparte, first made truce proposals to British foreign secretary Lord Grenville as early as 1799. Because of the hardline stance of Grenville and Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger, their distrust of Bonaparte and obvious defects in the proposals, they were rejected out of hand. However, Pitt resigned in February 1801 over domestic issues and was replaced by the more accommodating Henry Addington. At that point Britain was motivated by the danger of a war with Russia.[6]

Addington's foreign secretary, Robert Jenkinson, Lord Hawkesbury, immediately opened communications with Louis Guillaume Otto, the French commissary for prisoners of war in London through whom Bonaparte had made his earlier proposals. Hawkesbury stated that he wanted to open discussions on terms for a peace agreement. Otto, generally under detailed instructions from Bonaparte, engaged in negotiations with Hawkesbury in mid-1801. Unhappy with the dialogue with Otto, Hawkesbury sent diplomat Anthony Merry to Paris, who opened a second line of communications with the French foreign minister, Talleyrand. By mid-September, written negotiations had progressed to the point that Hawkesbury and Otto met to draft a preliminary agreement. On 30 September, they signed the preliminary agreement in London, which was published the next day.[7]

The terms of the preliminary agreement required Britain to restore most of the French colonial possessions that it had captured since 1794, to evacuate Malta and to withdraw from other occupied Mediterranean ports. Malta was to be restored to the Order of St. John, whose sovereignty was to be guaranteed by one or more powers, to be determined at the final peace. France was to restore Egypt to Ottoman control, to withdraw from most of the Italian peninsula and to agree to preserve Portuguese sovereignty. Ceylon, previously a Dutch territory, was to remain with the British, and Newfoundland fishery rights were to be restored to their prewar status. Britain was also to recognise the Seven Islands Republic, established by France on islands in the Ionian Sea that are now part of Greece. Both sides were to be allowed access to the outposts on the Cape of Good Hope.[8] In a blow to Spain, the preliminary agreement included a secret clause in which Trinidad was to remain with Britain.[9]

News of the signing was greeted across Europe with joy. The celebrations of peace, the pamphlets, poems, and odes proliferated in French, English, German, and other languages. Actors happily depicted the treaty at dinner theatres, vaudeville, and the legitimate stage. In Britain there were illuminations and fireworks. Peace, it was thought in Britain, would lead to the withdrawal of the income tax imposed by Pitt, a reduction of grain prices and a revival of markets.[10]

Final negotiations

In November 1801, Cornwallis was sent to France with plenipotentiary powers to negotiate a final agreement. The expectation among the British populace that peace was at hand put enormous pressure on Cornwallis, something that Bonaparte realised and capitalised on. The French negotiators, Napoleon's brother Joseph as well as Talleyrand, constantly shifted their positions, leaving Cornwallis to write, "I feel it as the most unpleasant circumstance attending this unpleasant business that, after I have obtained his acquiescence on any point, I can have no confidence that it is finally settled and that he will not recede from it in our next conversation."[11] The Batavian Republic, whose economy depended on trade that had been ruined by the war, appointed Rutger Jan Schimmelpenninck, its ambassador to France, to represent it in the peace negotiations. He arrived in Amiens on 9 December.[12] The Dutch role in the negotiations was marked by a lack of respect on the part of the French, who thought of them as a "vanquished and conquered" client whose present government "owed them everything."[13]

Schimmelpenninck and Cornwallis negotiated agreements on the status of Ceylon, which was to remain British; the Cape of Good Hope, which was to be returned to the Dutch but to be open to all; and the indemnification of the deposed House of Orange-Nassau for its losses. However, Joseph did not immediately agree to their terms, presumably needing to consult with the First Consul on the matter.[14]

In January 1802, Napoleon travelled to Lyon to accept the presidency of the Italian Republic, a nominally-independent French client republic that covered northern Italy and had been established in 1797. That act violated the Treaty of Lunéville, in which Bonaparte agreed to guarantee the independence of the Italian Republic and the other client republics. He also continued to support French General Pierre Augereau's reactionary coup d'état of 18 September 1801 in the Batavian Republic and its new constitution that was ratified by a sham election and brought the republic into closer alignment with its dominant partner.

British newspaper readers followed the events, presented in strong moralising colours. Hawkesbury wrote of Bonaparte's action at Lyons that it was a "gross breach of faith" exhibiting an "inclination to insult Europe." Writing from London, he informed Cornwallis that it "created the greatest alarm in this country, and there are many persons who were pacifically disposed and who since this event are desirous of renewing the war."[15]

The Spanish negotiator, the Marquis de Azara, did not arrive in Amiens until early February 1802. After some preliminary negotiations, he proposed to Cornwallis that Britain and Spain make a separate agreement, but Cornwallis rejected that in the belief that would jeopardise the more important negotiations with France.[16]

Pressure continued to mount on the British negotiators for a peace deal, in part because budget discussions were underway in Parliament, and the prospect of continued war was another significant factor. The principal sticking point in the late negotiations was the status of Malta. Bonaparte eventually proposed that the British were to withdraw within three months of signing, with control passed back to a recreated Order of St. John, whose sovereignty was to be guaranteed by all of the major European powers. Left unspecified in that proposal was the means by which the Order would be re-established; it had essentially dissolved upon French seizure of the island in 1798. Furthermore, none of the other powers had been consulted on the matter.[17]

On 14 March, London, under pressure to finalise the budget, gave Cornwallis a hard deadline. He was to return to London if he could not reach an agreement within eight days. Following a five-hour negotiating session that ended at 3 a.m. on 25 March, Cornwallis and Joseph signed the final agreement. Cornwallis was unhappy with the agreement, but he also worried about "the ruinous consequences of... renewing a bloody and hopeless war."[17]

Terms

The treaty, beyond confirming "peace, friendship, and good understanding," called for the following:

- The restoration of prisoners and hostages.

- Britain to return the Cape Colony to the Batavian Republic.

- Britain to return most of its captured Dutch Guiana to the Batavian Republic.

- Britain to withdraw its forces from Egypt.

- Spain agreeing to British rule of Trinidad[19]

- The Batavian Republic to cede Ceylon, previously under control of the United Provinces and the Dutch East India company, to Britain.[20]

- France to withdraw its forces from the Papal States and the Kingdom of Naples.

- French Guiana to have its borders defined.

- Malta, Gozo, and Comino to be restored to the Knights Hospitaller and to be declared neutral.

- Gibraltar to remain under British rule.

- Menorca be returned to Spain.

- The House of Orange-Nassau to be compensated for its losses in the Netherlands.

- The Septinsular Republic was recognized by the signatory parties.

Two days after signing the treaty, all four parties signed an addendum, specifically acknowledging that the failure to use the languages of all of the signatory powers (the treaty was published in English and French) was not prejudicial and should not be viewed as setting a precedent. It also stated that the omission of any individual's titles was unintentional and not intended to be prejudicial. The Dutch and French representatives signed a separate convention, clarifying that the Batavian Republic was not to be financially responsible for the compensation paid to the House of Orange-Nassau.[21]

Preliminaries were signed in London on 1 October 1801. King George proclaimed the cessation of hostilities on 12 October.

Amiens interlude

Upper-class British visitors flocked to Paris in the second half of 1802. William Herschel took the opportunity to confer with his colleagues at the Observatoire. In booths and temporary arcades in the courtyard of the Louvre, the third French exposition des produits français took place on 18–24 September. According to the memoirs of his private secretary, Fauvelet de Bourrienne, Bonaparte "was, above all, delighted with the admiration the exhibition excited among the numerous foreigners who resorted to Paris during the peace."[22]

Among the visitors was Charles James Fox, who received a personal tour from Minister Chaptal. Within the Louvre, in addition to the display of recent works in the Salon of 1802, visitors could see the display of Italian paintings and Roman sculptures collected from all over Italy under the stringent terms of the Treaty of Tolentino. J.M.W. Turner was able to fill a sketchbook from what he saw. Even the four Greek Horses of St Mark from Venice, which had been furtively removed in 1797, could now be viewed in an inner courtyard.[23] William Hazlitt arrived at Paris on 16 October 1802. The Roman sculptures did not move him, but he spent most of three months studying and copying Italian masters in the Louvre.[24]

The English were not the only ones to profit by the halcyon lull in hostilities. From London, the Russian Simon Vorontsov noted to a correspondent, "I hear that our gentlemen are making extravagant purchases in Paris. That fool Demidov has ordered a porcelain dinner service every plate of which costs 16 gold louis."[25]

For those who could not get there, Helmina von Chézy collected her impressions in a series of vignettes contributed to the journal Französische Miscellen,[26] and F. W. Blagdon[27] and John Carr[28] were among those who brought up to date curious English readers, who had felt starved for unbiased accounts of "a people under the influence [ ] of a political change, hitherto unparalleled.... During a separation of ten years, we have received very little account of this extraordinary people, which could be relied on," Carr noted in his Preface.

A number of French émigrés returned to France, under the terms of relaxed restrictions upon them.[29] French visitors also came to England. Wax artist Marie Tussaud came to London and established an exhibition similar to one she had in Paris. The balloonist André-Jacques Garnerin staged displays in London and made a balloon flight from London to Colchester in 45 minutes.[30]

The Spanish economy, which had been badly affected by the war, began to recover with the advent of peace.[31] Much as it had been at the start of the wars in 1793, Spain remained diplomatically caught between Britain and France, but in the period just after the signing of the Treaty of Amiens, a number of actions on the part of the French government antagonized the Spanish. France's unwillingness to block the cession of Trinidad to Britain was one of the things that most irritated King Carlos IV.[32] Spanish economic interests were further injured when Bonaparte sold Louisiana to the United States, whose merchants competed with those of Spain.[33] Following that sale, Carlos wrote that he was prepared to throw off alliance with France: "neither break with France, nor break with England."[34]

Breakdown

Britain ended the uneasy truce created by the Treaty of Amiens when it declared war on France in May 1803. The British were increasingly angered by Napoleon's re-ordering of the international system in Western Europe, especially in Switzerland, Germany, Italy and the Netherlands. Kagan argues that Britain was irritated in particular by Napoleon's assertion of control over Switzerland. Furthermore, Britons felt insulted when Napoleon stated that their country deserved no voice in European affairs, even though King George III was an elector of the Holy Roman Empire. For its part, Russia decided that the intervention in Switzerland indicated that Napoleon was not looking toward a peaceful resolution of his differences with the other European powers.[36] Britain was laboring under a sense of loss of control, as well as loss of markets, and was worried by Napoleon's possible threat to its overseas colonies. McLynn argues that Britain went to war in 1803 out of a "mixture of economic motives and national neuroses – an irrational anxiety about Napoleon's motives and intentions." However, it proved to be the right choice for Britain, because in the long run Napoleon’s intentions were hostile to British national interests. Furthermore, Napoleon was not ready for war, and it was the best time for Britain to try to stop him.[37] Britain therefore seized upon the Malta issue by refusing to follow the terms of the Treaty of Amiens that required its evacuation of the island.

Schroeder says that most historians agree that Napoleon's "determination to exclude Britain from the Continent now, and bring it to its knees in the future, made war...inevitable."[38] The British government balked at implementing certain terms of the treaty, such as evacuating their naval presence from Malta. After the initial fervour, objections to the treaty quickly grew in Britain, where it seemed to the governing class that they were making all the concessions and ratifying recent developments. Prime Minister Addington did not undertake military demobilisation, but maintained a large peacetime army of 180,000.[39]

Actions taken by Bonaparte after the treaty was signed heightened tensions with Britain and signatories to the other treaties. He used the time of peace to consolidate power and reorganise domestic administration in France and some of its client states. His effective annexation of the Cisalpine Republic and his decision to send French troops into the Helvetian Republic (Switzerland) in October 1802, was another violation of Lunéville. However, Britain had not signed the Treaty of Lunéville, and the powers that had signed it tolerated Napoleon's actions. Tsar Alexander had just congratulated Bonaparte for withdrawing from there and other places, but the Swiss move increased the belief in his cabinet that Bonaparte was not to be trusted. Bonaparte met British protests over the action with belligerent statements, again denying Britain's right to be formally involved in matters on the continent and pointing out that Switzerland had been occupied by French troops when the treaty was signed.[40] He also demanded for the British government to censor the strongly anti-French British press and to expel French expatriates from British soil. Those demands were perceived in London as affronts to British sovereignty.[41]

Bonaparte also took advantage of the loosening of the British blockade of French ports to organise and dispatch a naval expedition to regain control over revolutionary Haiti and to occupy French Louisiana. Those moves were perceived by the British as a willingness by Bonaparte to threaten them on a global stage.[41]

Britain refused to remove troops from Egypt or Malta, as agreed upon in the treaty.[42] Bonaparte formally protested the continuing British occupations and, in January 1803, published a report by Horace Sebastiani that included observations on the ease with which France might capture Egypt, alarming most of the European powers.[42][43] In an interview in February 1803 with Lord Whitworth, Britain's French ambassador, Bonaparte threatened war if Malta was not evacuated and implied that he could have already retaken Egypt.[44] The exchange left Whitworth feeling he was given an ultimatum. In a public meeting with a group of diplomats the following month, Bonaparte again pressed Whitworth, implying that the British wanted war since they were not upholding their treaty obligations.[44] The Russian ambassador, Arkadiy Ivanovich Morkov, reported the encounter back to St. Petersburg in stark terms. The implicit and explicit threats contained in the exchange may have played a role in Russia's eventual entry into the Third Coalition.[45] Morkov also reported rumours that Bonaparte would seize Hamburg as well as Hanover if war was renewed.[46] Although Alexander wanted to avoid war, that news apparently forced his hand; he began collecting troops on the Baltic coast in late March.[47] The Russian foreign minister wrote of the situation, "The intention already expressed by the First Consul of striking blows against England wherever he can, and under this pretext of sending his troops into Hanover [and] Northern Germany... entirely transforms the nature of this war as it relates to our interests and obligations."[48]

When France moved to occupy Switzerland, the British had issued orders for their military not to return Cape Colony to the Dutch, as stipulated in the Treaty of Amiens, only to countermand them when the Swiss failed to resist. In March 1803, the British ministry received notice that Cape Colony had been reoccupied by the military, and it promptly ordered military preparations to guard against possible French retaliation for the breach of the treaty. They falsely claimed that hostile French preparations had forced them into that action and that they were engaged in serious negotiations. To cover up their deception, the ministry issued a sudden ultimatum to France, demanding an evacuation of Holland and Switzerland and British control of Malta for ten years.[49] The exchange prompted an exodus of foreigners from France, and Bonaparte quickly sold Louisiana to the United States to prevent its capture by Britain. Bonaparte made "every concession that could be considered as demanded or even imposed by the British government" by offering to guarantee the integrity of the Ottoman Empire, place Malta in the hands of a neutral third party and form a convention to satisfy Britain on other issues.[50] His rejection of a British offer involving a ten-year lease of Malta prompted the reactivation of the British blockade of the French coast. Bonaparte, who was not fully prepared to resume the war, made moves designed to show renewed preparations for an invasion of Britain.[51] Matters reached a diplomatic crisis point when the British rejected the idea of mediation by Tsar Alexander and, on 10 May, ordered Whitworth to withdraw from Paris if the French did not accede to their demands in 36 hours.[52] Last-minute attempts at negotiation by Talleyrand failed, and Whitworth left France on 13 May. Britain declared war on France on 18 May, thus starting the Napoleonic Wars, which would rage in Europe for the following 12 years.[53]

Britain gave its official reasons for resuming hostilities as France's imperialist policies in the West Indies, Italy, and Switzerland.[54]

War

On 17 May 1803, before the official declaration of war and without any warning, the Royal Navy captured all the French and Dutch merchant ships stationed in Britain or sailing around, seizing more than 2 million pounds of commodities and taking their crews as prisoners. In response to that provocation, on 22 May (2 Prairial, year XI), the First Consul ordered the arrest of all British males between the ages of 18 and 60 in France and Italy, trapping many travelling civilians. The acts were denounced as illegal by all the major powers. Bonaparte claimed in the French press that the British prisoners that he had taken amounted to 10,000, but French documents compiled in Paris a few months later show that the numbers were 1,181. It was not until the abdication of Bonaparte in 1814 that the last of the imprisoned British civilians were allowed to return home.[55]

Addington proved an ineffective prime minister in wartime and was replaced on 10 May 1804 with William Pitt, who formed the Third Coalition. Pitt was involved in failed assassination attempts on Bonaparte's life by Cadoudal and Pichegru.[56]

Napoleon, now Emperor of the French, assembled armies on the coast of France to invade Great Britain, but Austria and Russia, Britain's allies, were preparing to invade France. The French armies were christened La Grande Armée and secretly left the coast to march against Austria and Russia before those armies could combine. The Grande Armée defeated Austria at Ulm the day before the Battle of Trafalgar, and Napoleon's victory at the Battle of Austerlitz effectively destroyed the Third Coalition. In 1806, Britain retook the Cape Colony from the Batavian Republic. Napoleon abolished the republic later that year in favour of the Kingdom of Holland, ruled by his brother Louis. However, in 1810, the Netherlands officially became a part of France.

Notes

- Ole Feldbæk, "The Anglo‐Russian Rapprochement of 1801: A prelude to the peace of Amiens." Scandinavian Journal of History 3.1-4 (1978): 205-227.

- Steven Englund, Napoleon: A Political Life (2005) pp 216-37.

- David Johnson, "Amiens 1802: the phoney peace" History Today (2002) 52#9, pp. 20-6.

- Alexander DeConde, This affair of Louisiana (1976)

- John D. Grainger, The Amiens Truce: Britain and Bonaparte, 1801-1803 (2004) chapter 1.

- Schroeder (1994) p 217

- D. Grainger, The Amiens Truce (2004) chapter 2.

- Dorman, p. 281

- Hume, p. 61

- Steven Englund (2010). Napoleon: A Political Life. Simon and Schuster. pp. 252–54.

- Bryant, p. 388.

- Grainger, p. 68

- Blok, p. 342.

- Grainger, p. 70

- Bryant, p. 389

- Grainger, p. 72

- Bryant, p. 390

- Joseph Bonaparte portrait by Luigi Toro.

- https://www.napoleon-empire.com/official-texts/treaty-of-amiens.php

- https://www.napoleon-empire.com/official-texts/treaty-of-amiens.php

- Burke, p. 614

- Quoted by Arthur Chandler, "The Napoleonic Expositions" Archived 25 November 2003 at Archive.today

- Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny, Taste and the Antique (Yale University Press) 1981, pp ch xiv 'The Last Dispersals'.

- "I say nothing of the statues; for I know but little of sculpture, and never liked any till I saw the Elgin Marbles.... Here, for four months together, I strolled and studied." (Hazlitt, Table Talk:" "On The Pleasure of Painting").

- Quoted in Fernand Braudel, Civilization & Capitalism: III. The Perspective of the World 1984:465.

- Analyzed in K. Baumgartner, "Constructing Paris: flânerie, female spectatorship, and the discourses of fashion in Französische Miscellen (1803)", 'Monatshefte, 2008

- Blagdon, Paris as it was and as it is: or, A sketch of the French capital, illustrative of the effects of the revolution, with respect to sciences, literature, arts, religion..., (London 1803)

- Carr, The stranger in France, or, A tour from Devonshire to Paris, (London 1803).

- John Carr described the bustle of returning emigrés on the docks at Southampton.

- Grainger, p. 131

- Schneid, pp. 25–26

- Schneid, p. 25

- Schneid, p. 27-28

- Schneid, p. 28

- Andrew Roberts, Napoleon: A Life (2014) p 316

- Frederick Kagan, The End of the Old Order: Napoleon and Europe, 1801-1805 (2007) pp 42-43

- McLynn, Napoleon: A Biography (1997) p. 69

- Schroeder (1994) p 242-43

- Frank O'Gorman,The Long Eighteenth Century, p. 236

- Kagan, p. 40

- Kagan, p. 41

- Kagan, p. 42

- Grainger, p. 153

- Kagan, p. 43

- Kagan, p. 44

- Kagan, p. 46

- Kagan, pp. 46–8.

- Kagan, p. 49

- Annual Register (1803) pp. 273-278

- Annual Register (1803) p. 277

- Pocock, p. 76

- Pocock, p. 77

- Pocock, p. 78

- Illustrated History of Europe: A Unique Guide to Europe's Common Heritage (1992) p. 282

- Frederick C. Schneid, Napoleon's conquest of Europe: the War of the Third Coalition (Greenwood, 2005).

- Tom Pocock (2005). The Terror Before Trafalgar: Nelson, Napoleon, and the Secret War. Naval Institute Press. p. 111.

References and further reading

- Blok, Petrus Johannes (1912). History of the People of the Netherlands. New York and London: G. P. Putnam's. p. 341. OCLC 1721795.

- Bryant, Sir Arthur (1942). The Years of Endurance 1793–1802.

- Burke, Edmund (ed) (1803). Annual Register, Volume 44. London: Longman and Greens. OCLC 191704722.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Dorman, Robert Marcus Phipps (1902). A history of the British empire in the nineteenth century, Volume 1. London: Kegan, Paul, Trench, and Trüber. p. 281. OCLC 633662790.

- Dwyer, Philip. Citizen Emperor: Napoleon in Power (2013)

- Emsley, Clive. Napoleonic Europe (Routledge, 2014)

- Esdaile, Charles J. Napoleon's Wars: And International History: 1803 – 1815 (2007) pp 110–53

- Grainger, John D. The Amiens Truce: Britain and Bonaparte, 1801-1803 (2004). online review

- Hume, Mark Andrew Sharp (1900). Modern Spain 1788–1898. New York: G. P. Putnam's. p. 62. OCLC 2946787.

- Kagan, Frederick W (2006). The End of the Old Order: Napoleon and Europe 1801–1805 (paperback ed.). Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press. pp. 11–50. ISBN 0-306-81137-5.

- Lokke, Carl Ludwig. "Secret Negotions to Maintain the Peace of Amiens." American Historical Review 49.1 (1943): 55-64. online

- Pocock, Tom (2005). The Terror Before Trafalgar: Nelson, Napoleon, And The Secret War. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-681-0. OCLC 56419314.

- Schneid, Frederick C (2005). Napoleon's Conquest of Europe: the War of the Third Coalition. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-98096-2. OCLC 57134421.

- Schroeder, Paul W. The transformation of European politics, 1763-1848 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994)

External links

| Wikisource has the original text of the treaty: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Treaty of Amiens. |

- Cobbett's Annual Register 1803 contains much of the correspondence, principally involving French or British participants

- Cobbett's Annual Register 1802 contains the treaty text

- Napoleon's British visitors contains accounts of British visits to France during the interlude