Political corruption

Political corruption or Malpolitics is the use of powers by government officials or their network contacts for illegitimate private gain.

| Political corruption | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concepts | ||||||||||||

| Corruption by country | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

Forms of corruption vary, but can include bribery, extortion, cronyism, nepotism, parochialism, patronage, influence peddling, graft, and embezzlement. Corruption may facilitate criminal enterprise such as drug trafficking, money laundering, and human trafficking, though it is not restricted to these activities. Misuse of government power for other purposes, such as repression of political opponents and general police brutality, is also considered political corruption.

Over time, corruption has been defined differently. For example, in a simple context, while performing work for a government or as a representative, it is unethical to accept a gift. Any free gift could be construed as a scheme to lure the recipient towards some biases. In most cases, the gift is seen as an intention to seek certain favors such as work promotion, tipping in order to win a contract, job or exemption from certain tasks in the case of junior worker handing in the gift to a senior employee who can be key in winning the favor.[1]

Some forms of corruption – now called "institutional corruption"[2] – are distinguished from bribery and other kinds of obvious personal gain. A similar problem of corruption arises in any institution that depends on financial support from people who have interests that may conflict with the primary purpose of the institution.

An illegal act by an officeholder constitutes political corruption only if the act is directly related to their official duties, is done under color of law or involves trading in influence. The activities that constitute illegal corruption differ depending on the country or jurisdiction. For instance, some political funding practices that are legal in one place may be illegal in another. In some cases, government officials have broad or ill-defined powers, which make it difficult to distinguish between legal and illegal actions. Worldwide, bribery alone is estimated to involve over 1 trillion US dollars annually.[3] A state of unrestrained political corruption is known as a kleptocracy, literally meaning "rule by thieves".

Effects

Effects on politics, administration, and institutions

In politics, corruption undermines democracy and good governance by flouting or even subverting formal processes. Corruption in elections and in the legislature reduces accountability and distorts representation in policymaking; corruption in the judiciary compromises the rule of law; and corruption in public administration results in the inefficient provision of services. For republics, it violates a basic principle of republicanism regarding the centrality of civic virtue.[4] More generally, corruption erodes the institutional capacity of government if procedures are disregarded, resources are siphoned off, and public offices are bought and sold. Corruption undermines the legitimacy of government and such democratic values as trust and tolerance. Recent evidence suggests that variation in the levels of corruption amongst high-income democracies can vary significantly depending on the level of accountability of decision-makers.[4] Evidence from fragile states also shows that corruption and bribery can adversely impact trust in institutions.[5][6] Corruption can also impact government's provision of goods and services. It increases the costs of goods and services which arise from efficiency loss. In the absence of corruption, governmental projects might be cost-effective at their true costs, however, once corruption costs are included projects may not be cost-effective so they are not executed distorting the provision of goods and services.[7]

Economic effects

In the private sector, corruption increases the cost of business through the price of illicit payments themselves, the management cost of negotiating with officials and the risk of breached agreements or detection. Although some claim corruption reduces costs by cutting bureaucracy, the availability of bribes can also induce officials to contrive new rules and delays. Openly removing costly and lengthy regulations are better than covertly allowing them to be bypassed by using bribes. Where corruption inflates the cost of business, it also distorts the field of inquiry and action, shielding firms with connections from competition and thereby sustaining inefficient firms.[8]

Corruption may have a direct impact on the firm's effective marginal tax rate. Bribing tax officials can reduce tax payments of the firm if the marginal bribe rate is below the official marginal tax rate.[7] However, in Uganda, bribes have a higher negative impact on firms’ activity than taxation. Indeed, a one percentage point increase in bribes reduces firm's annual growth by three percentage points, while an increase in 1 percentage point on taxes reduces firm's growth by one percentage point.[9]

Corruption also generates economic distortion in the public sector by diverting public investment into capital projects where bribes and kickbacks are more plentiful. Officials may increase the technical complexity of public sector projects to conceal or pave the way for such dealings, thus further distorting investment.[10] Corruption also lowers compliance with construction, environmental, or other regulations, reduces the quality of government services and infrastructure, and increases budgetary pressures on government.

Economists argue that one of the factors behind the differing economic development in Africa and Asia is that in Africa, corruption has primarily taken the form of rent extraction with the resulting financial capital moved overseas rather than invested at home (hence the stereotypical, but often accurate, image of African dictators having Swiss bank accounts). In Nigeria, for example, more than $400 billion was stolen from the treasury by Nigeria's leaders between 1960 and 1999.[11]

University of Massachusetts Amherst researchers estimated that from 1970 to 1996, capital flight from 30 Sub-Saharan countries totaled $187bn, exceeding those nations' external debts.[12] (The results, expressed in retarded or suppressed development, have been modeled in theory by economist Mancur Olson.) In the case of Africa, one of the factors for this behavior was political instability and the fact that new governments often confiscated previous government's corruptly obtained assets. This encouraged officials to stash their wealth abroad, out of reach of any future expropriation. In contrast, Asian administrations such as Suharto's New Order often took a cut on business transactions or provided conditions for development, through infrastructure investment, law and order, etc.

Environmental and social effects

Corruption is often most evident in countries with the smallest per capita incomes, relying on foreign aid for health services. Local political interception of donated money from overseas is especially prevalent in Sub-Saharan African nations, where it was reported in the 2006 World Bank Report that about half of the funds that were donated for health usages were never invested into the health sectors or given to those needing medical attention.[13]

Instead, the donated money was expended through "counterfeit drugs, siphoning off of drugs to the black market, and payments to ghost employees". Ultimately, there is a sufficient amount of money for health in developing countries, but local corruption denies the wider citizenry the resource they require.[13]

Corruption facilitates environmental destruction. While corrupt societies may have formal legislation to protect the environment, it cannot be enforced if officials can easily be bribed. The same applies to social rights worker protection, unionization prevention, and child labor. Violation of these laws rights enables corrupt countries to gain illegitimate economic advantage in the international market.

The Nobel Prize-winning economist Amartya Sen has observed that "there is no such thing as an apolitical food problem." While drought and other naturally occurring events may trigger famine conditions, it is government action or inaction that determines its severity, and often even whether or not a famine will occur.[14]

Governments with strong tendencies towards kleptocracy can undermine food security even when harvests are good. Officials often steal state property. In Bihar, India, more than 80% of the subsidized food aid to poor is stolen by corrupt officials.[14] Similarly, food aid is often robbed at gunpoint by governments, criminals, and warlords alike, and sold for a profit. The 20th century is full of many examples of governments undermining the food security of their own nations – sometimes intentionally.[15]

Effects on humanitarian aid

The scale of humanitarian aid to the poor and unstable regions of the world grows, but it is highly vulnerable to corruption, with food aid, construction and other highly valued assistance as the most at risk.[16] Food aid can be directly and physically diverted from its intended destination, or indirectly through the manipulation of assessments, targeting, registration and distributions to favor certain groups or individuals.[16]

In construction and shelter there are numerous opportunities for diversion and profit through substandard workmanship, kickbacks for contracts and favouritism in the provision of valuable shelter material.[16] Thus while humanitarian aid agencies are usually most concerned about aid being diverted by including too many, recipients themselves are most concerned about exclusion.[16] Access to aid may be limited to those with connections, to those who pay bribes or are forced to give sexual favors.[16] Equally, those able to do so may manipulate statistics to inflate the number of beneficiaries and siphon off additional assistance.[16]

Malnutrition, illness, wounds, torture, harassment of specific groups within the population, disappearances, extrajudicial executions and the forcible displacement of people are all found in many armed conflicts. Aside from their direct effects on the individuals concerned, the consequences of these tragedies for local systems must also be considered: the destruction of crops and places of cultural importance, the breakdown of economic infrastructure and of health-care facilities such as hospitals, etc., etc.[17]

Effects on health

Corruption plays a huge role in health care system starting from the hospital, to the government and lifted to the other institutions that promote quality and affordable health care to the people. The efficiency of health care delivery in any country is heavily dependent on accountable and transparent systems, proper management of both financial and human resources and timely supply of services to the vulnerable populace of the nation.[18]

At the basic level, greed skyrockets corruption. When the structure of the health care system is not adequately addressed beginning from oversight in healthcare delivery and supply of drugs and tendering process, mismanagement and misappropriation of funds will always be observed. Corruption also can undermine health care service delivery which in turn disorients the lives of the poor. Corruption leads to violation of human rights and fundamental freedoms as people supposed to benefit from the basic health care from the governments are denied due to unscrupulous processes driven by greed. Therefore, for a country to keep citizens healthy there must be efficient systems and proper resources that can tame the evils like corruption that underpin it.

Effects on education

Education forms the basis and the fabric in which a society is transformed and different facets of well-being are shaped. Corruption in higher education has been prevalent and calls for immediate intervention. Increased corruption in higher education has led to growing global concern among governments, students and educators and other stakeholders. Those offering services in the higher education institutions are facing pressure that highly threatens the integral value of higher education enterprise. Corruption in higher education has a larger negative influence, it destroys the relation between personal effort and reward anticipation. Moreover, employees and students develop a belief that personal success does not come from hard work and merit but through canvassing with teachers and taking other shortcuts.[19] Academic promotions in the higher education institutions have been disabled by unlimited corruption. Presently, promotion is based on personal connections than professional achievements. This has led to dramatic increase in the number of professors and exhibits their rapid status loss.[20] Utmost the flawed processes in the academic institutions has led to unbaked graduates who are not well fit to the job market. Corruption hinders the international standards of an education system. Additionally, Plagiarism is a form of corruption in academic research, where it affects originality and disables learning. Individual violations are in close relation to the operation ways of a system. Furthermore, the universities may be in relationships and dealings with business and people in government, which majority of them enrol in doctoral studies without the undergraduate program.Consequently, money, power and related influence compromise education standards since they are fueling factors. A Student may finish thesis report within a shorter time upon which compromises the quality of work delivered and questions the threshold of the higher education.[21]

Other areas: public safety, trade unions, police corruption, etc.

Corruption is not specific to poor, developing, or transition countries. In western countries, cases of bribery and other forms of corruption in all possible fields exist: under-the-table payments made to reputed surgeons by patients attempting to be on top of the list of forthcoming surgeries,[22] bribes paid by suppliers to the automotive industry in order to sell low-quality connectors used for instance in safety equipment such as airbags, bribes paid by suppliers to manufacturers of defibrillators (to sell low-quality capacitors), contributions paid by wealthy parents to the "social and culture fund" of a prestigious university in exchange for it to accept their children, bribes paid to obtain diplomas, financial and other advantages granted to unionists by members of the executive board of a car manufacturer in exchange for employer-friendly positions and votes, etc. Examples are endless.

These various manifestations of corruption can ultimately present a danger for public health; they can discredit specific, essential institutions or social relationships. Osipian summarized a 2008 "study of corruption perceptions among Russians ... .30 percent of the respondents marked the level of corruption as very high, while another 44 percent as high. 19 percent considered it as average and only 1 percent as low. The most corrupt in people's minds are traffic police (33 percent), local authorities (28 percent), police (26 percent), healthcare (16 percent), and education (15 percent). 52 percent of the respondents had experiences of giving money or gifts to medical professionals while 36 percent made informal payments to educators." He claimed that this corruption lowered the rate of economic growth in Russia, because the students disadvantaged by this corruption could not adopt better work methods as quickly, lowering thereby total factor productivity for Russia.[23]

Corruption can also affect the various components of sports activities (referees, players, medical and laboratory staff involved in anti-doping controls, members of national sport federation and international committees deciding about the allocation of contracts and competition places).

Cases exist against (members of) various types of non-profit and non-government organizations, as well as religious organizations.

Ultimately, the distinction between public and private sector corruption sometimes appears rather artificial, and national anti-corruption initiatives may need to avoid legal and other loopholes in the coverage of the instruments.

Types

Bribery

In the context of political corruption, a bribe may involve a payment given to a government official in exchange of his use of official powers. Bribery requires two participants: one to give the bribe, and one to take it. Either may initiate the corrupt offering; for example, a customs official may demand bribes to let through allowed (or disallowed) goods, or a smuggler might offer bribes to gain passage. In some countries the culture of corruption extends to every aspect of public life, making it extremely difficult for individuals to operate without resorting to bribes. Bribes may be demanded in order for an official to do something he is already paid to do. They may also be demanded in order to bypass laws and regulations. In addition to their role in private financial gain, bribes are also used to intentionally and maliciously cause harm to another (i.e. no financial incentive). In some developing nations, up to half of the population has paid bribes during the past 12 months.[24]

The Council of Europe dissociates active and passive bribery and to incriminates them as separate offences:

- One can define active bribery as "the promising, offering or giving by any person, directly or indirectly, of any undue advantage to any of its public officials, for himself or herself or for anyone else, for him or her to act or refrain from acting in the exercise of his or her functions" (article 2 of the Criminal Law Convention on Corruption (ETS 173)[25] of the Council of Europe).

- Passive bribery can be defined as "when committed intentionally, the request or receipt by any [...] public officials, directly or indirectly, of any undue advantage, for himself or herself or for anyone else, or the acceptance of an offer or a promise of such an advantage, to act or refrain from acting in the exercise of his or her functions" (article 3 of the Criminal Law Convention on Corruption (ETS 173)).[25]

This dissociation aims to make the early steps (offering, promising, requesting an advantage) of a corrupt deal already an offence and, thus, to give a clear signal (from a criminal-policy point-of-view) that bribery is not acceptable. Furthermore, such a dissociation makes the prosecution of bribery offences easier since it can be very difficult to prove that two parties (the bribe-giver and the bribe-taker) have formally agreed upon a corrupt deal. In addition, there is often no such formal deal but only a mutual understanding, for instance when it is common knowledge in a municipality that to obtain a building permit one has to pay a "fee" to the decision maker to obtain a favorable decision. A working definition of corruption is also provided as follows in article 3 of the Civil Law Convention on Corruption (ETS 174):[26] For the purpose of this Convention, "corruption" means requesting, offering, giving or accepting, directly or indirectly, a bribe or any other undue advantage or prospect thereof, which distorts the proper performance of any duty or behavior required of the recipient of the bribe, the undue advantage or the prospect thereof.

Trading in influence

Trading in influence, or influence peddling, refers a person selling his/her influence over the decision making process to benefit a third party (person or institution). The difference with bribery is that this is a tri-lateral relation. From a legal point of view, the role of the third party (who is the target of the influence) does not really matter although he/she can be an accessory in some instances. It can be difficult to make a distinction between this form of corruption and some forms of extreme and loosely regulated lobbying where for instance law- or decision-makers can freely "sell" their vote, decision power or influence to those lobbyists who offer the highest compensation, including where for instance the latter act on behalf of powerful clients such as industrial groups who want to avoid the passing of specific environmental, social, or other regulations perceived as too stringent, etc. Where lobbying is (sufficiently) regulated, it becomes possible to provide for a distinctive criteria and to consider that trading in influence involves the use of "improper influence", as in article 12 of the Criminal Law Convention on Corruption (ETS 173)[25] of the Council of Europe.

Patronage

Patronage refers to favoring supporters, for example with government employment. This may be legitimate, as when a newly elected government changes the top officials in the administration in order to effectively implement its policy. It can be seen as corruption if this means that incompetent persons, as a payment for supporting the regime, are selected before more able ones. In nondemocracies many government officials are often selected for loyalty rather than ability. They may be almost exclusively selected from a particular group (for example, Sunni Arabs in Saddam Hussein's Iraq, the nomenklatura in the Soviet Union, or the Junkers in Imperial Germany) that support the regime in return for such favors. A similar problem can also be seen in Eastern Europe, for example in Romania, where the government is often accused of patronage (when a new government comes to power it rapidly changes most of the officials in the public sector).[27]

Nepotism and cronyism

Favoring relatives (nepotism) or personal friends (cronyism) of an official is a form of illegitimate private gain. This may be combined with bribery, for example demanding that a business should employ a relative of an official controlling regulations affecting the business. The most extreme example is when the entire state is inherited, as in North Korea or Syria. A lesser form might be in the Southern United States with Good ol' boys, where women and minorities are excluded. A milder form of cronyism is an "old boy network", in which appointees to official positions are selected only from a closed and exclusive social network – such as the alumni of particular universities – instead of appointing the most competent candidate.

Seeking to harm enemies becomes corruption when official powers are illegitimately used as means to this end. For example, trumped-up charges are often brought up against journalists or writers who bring up politically sensitive issues, such as a politician's acceptance of bribes.

Gombeenism and parochialism

Gombeenism refers to an individual who is dishonest and corrupt for the purpose of personal gain, more often through monetary, while, parochialism which is also known as parish pump politics relates to placing local or vanity projects ahead of the national interest.[28][29][30][31] For instance in Irish politics, populist left wing political parties will often apply these terms to mainstream establishment political parties and will cite the many cases of Corruption in Ireland, such as the Irish Banking crisis, which found evidence of bribery, cronyism and collusion, where in some cases politicians who were coming to the end of their political careers would receive a senior management or committee position in a company they had dealings with.

Electoral fraud

Electoral fraud is illegal interference with the process of an election. Acts of fraud affect vote counts to bring about an election result, whether by increasing the vote share of the favored candidate, depressing the vote share of the rival candidates, or both. Also called voter fraud, the mechanisms involved include illegal voter registration, intimidation at polls, voting computer hacking, and improper vote counting.

Embezzlement

Embezzlement is the theft of entrusted funds. It is political when it involves public money taken by a public official for use by anyone not specified by the public. A common type of embezzlement is that of personal use of entrusted government resources; for example, when an official assigns public employees to renovate his own house.

Kickbacks

A kickback is an official's share of misappropriated funds allocated from his or her organization to an organization involved in corrupt bidding. For example, suppose that a politician is in charge of choosing how to spend some public funds. He can give a contract to a company that is not the best bidder, or allocate more than they deserve. In this case, the company benefits, and in exchange for betraying the public, the official receives a kickback payment, which is a portion of the sum the company received. This sum itself may be all or a portion of the difference between the actual (inflated) payment to the company and the (lower) market-based price that would have been paid had the bidding been competitive.

Another example of a kickback would be if a judge receives a portion of the profits that a business makes in exchange for his judicial decisions.

Kickbacks are not limited to government officials; any situation in which people are entrusted to spend funds that do not belong to them are susceptible to this kind of corruption.

Unholy alliance

An unholy alliance is a coalition among seemingly antagonistic groups for ad hoc or hidden gain, generally some influential non-governmental group forming ties with political parties, supplying funding in exchange for the favorable treatment. Like patronage, unholy alliances are not necessarily illegal, but unlike patronage, by its deceptive nature and often great financial resources, an unholy alliance can be much more dangerous to the public interest. An early use of the term was by former US President Theodore "Teddy" Roosevelt:

- "To destroy this invisible Government, to dissolve the unholy alliance between corrupt business and corrupt politics is the first task of the statesmanship of the day." – 1912 Progressive Party Platform, attributed to Roosevelt[32] and quoted again in his autobiography,[33] where he connects trusts and monopolies (sugar interests, Standard Oil, etc.) to Woodrow Wilson, Howard Taft, and consequently both major political parties.

Involvement in organized crime

_(cropped).jpg)

An illustrative example of official involvement in organized crime can be found from the 1920s and 1930s Shanghai, where Huang Jinrong was a police chief in the French concession, while simultaneously being a gang boss and co-operating with Du Yuesheng, the local gang ringleader. The relationship kept the flow of profits from the gang's gambling dens, prostitution, and protection rackets undisturbed and safe .

The United States accused Manuel Noriega's government in Panama of being a "narcokleptocracy", a corrupt government profiting on illegal drug trade. Later the U.S. invaded Panama and captured Noriega.

Conditions favorable for corruption

It is argued that the following conditions are favorable for corruption:

- Information deficits

- Lacking freedom of information legislation. In contrast, for example: The Indian Right to Information Act 2005 is perceived to have "already engendered mass movements in the country that is bringing the lethargic, often corrupt bureaucracy to its knees and changing power equations completely."[35]

- Lack of investigative reporting in the local media.[36]

- Contempt for or negligence of exercising freedom of speech and freedom of the press.

- Weak accounting practices, including lack of timely financial management.

- Lack of measurement of corruption. For example, using regular surveys of households and businesses in order to quantify the degree of perception of corruption in different parts of a nation or in different government institutions may increase awareness of corruption and create pressure to combat it. This will also enable an evaluation of the officials who are fighting corruption and the methods used.

- Tax havens which tax their own citizens and companies but not those from other nations and refuse to disclose information necessary for foreign taxation. This enables large-scale political corruption in the foreign nations.[37]

- Lacking control of the government.

- Lacking civic society and non-governmental organizations which monitor the government.

- An individual voter may have a rational ignorance regarding politics, especially in nationwide elections, since each vote has little weight.

- Weak civil service, and slow pace of reform.

- Weak rule of law.

- Weak legal profession.

- Weak judicial independence.

- Lacking protection of whistleblowers.

- Lack of benchmarking, that is continual detailed evaluation of procedures and comparison to others who do similar things, in the same government or others, in particular comparison to those who do the best work. The Peruvian organization Ciudadanos al Dia has started to measure and compare transparency, costs, and efficiency in different government departments in Peru. It annually awards the best practices which has received widespread media attention. This has created competition among government agencies in order to improve.[38]

- Individual officials routinely handle cash, instead of handling payments by giro or on a separate cash desk – illegitimate withdrawals from supervised bank accounts are much more difficult to conceal.

- Public funds are centralized rather than distributed. For example, if $1,000 is embezzled from a local agency that has $2,000 funds, it is easier to notice than from a national agency with $2,000,000 funds. See the principle of subsidiarity.

- Large, unsupervised public investments.

- Pay disproportionately lower than that of the average citizen.

- Government licenses needed to conduct business, e.g., import licenses, encourage bribing and kickbacks.

- Long-time work in the same position may create relationships inside and outside the government which encourage and help conceal corruption and favoritism. Rotating government officials to different positions and geographic areas may help prevent this; for instance certain high rank officials in French government services (e.g. treasurer-paymasters general) must rotate every few years.

- Costly political campaigns, with expenses exceeding normal sources of political funding, especially when funded with taxpayer money.

- A single group or family controlling most of the key government offices. Lack of laws forbidding and limiting number of members of the same family to be in office .

- Less interaction with officials reduces the opportunities for corruption. For example, using the Internet for sending in required information, like applications and tax forms, and then processing this with automated computer systems. This may also speed up the processing and reduce unintentional human errors. See e-Government.

- A windfall from exporting abundant natural resources may encourage corruption.[39] (See Resource curse)

- War and other forms of conflict correlate with a breakdown of public security.

- Social conditions

- Self-interested closed cliques and "old boy networks".

- Family-, and clan-centered social structure, with a tradition of nepotism/favouritism being acceptable.

- A gift economy, such as the Soviet blat system, emerges in a Communist centrally planned economy.

- Lacking literacy and education among the population.

- Frequent discrimination and bullying among the population.

- Tribal solidarity, giving benefits to certain ethnic groups. In the Indian political system, for example, it has become common that the leadership of national and regional parties are passed from generation to generation[40][41], creating a system in which a family holds the center of power. Some examples are most of the Dravidian parties of south India and also the Nehru-Gandhi family of the Congress party, which is one of the two major political parties in India.

- Lack of strong laws which forbid members of the same family to contest elections and be in office as in India where local elections are often contested between members of the same powerful family by standing in opposite parties so that whoever is elected that particular family is at tremendous benefit.

Media

Thomas Jefferson observed a tendency for "The functionaries of every government ... to command at will the liberty and property of their constituents. There is no safe deposit [for liberty and property] ... without information. Where the press is free, and every man able to read, all is safe."

Recent research supports Jefferson's claim. Brunetti and Weder found "evidence of a significant relationship between more press freedom and less corruption in a large cross-section of countries." They also presented "evidence which suggests that the direction of causation runs from higher press freedom to lower corruption."[42] Adserà, Boix, and Payne found that increases in newspaper readership led to increased political accountability and lower corruption in data from roughly 100 countries and from different states in the US.[43]

Snyder and Strömberg found "that a poor fit between newspaper markets and political districts reduces press coverage of politics. ... Congressmen who are less covered by the local press work less for their constituencies: they are less likely to stand witness before congressional hearings ... . Federal spending is lower in areas where there is less press coverage of the local members of congress."[44] Schulhofer-Wohl and Garrido found that the year after the Cincinnati Post closed in 2007, "fewer candidates ran for municipal office in the Kentucky suburbs most reliant on the Post, incumbents became more likely to win re-election, and voter turnout and campaign spending fell.[45]

An analysis of the evolution of mass media in the United States and European Union since World War II noted mixed results from the growth of the Internet: "The digital revolution has been good for freedom of expression [and] information [but] has had mixed effects on freedom of the press": It has disrupted traditional sources of funding, and new forms of Internet journalism have replaced only a tiny fraction of what's been lost.[46]

Size of public sector

Extensive and diverse public spending is, in itself, inherently at risk of cronyism, kickbacks, and embezzlement. Complicated regulations and arbitrary, unsupervised official conduct exacerbate the problem. This is one argument for privatization and deregulation. Opponents of privatization see the argument as ideological. The argument that corruption necessarily follows from the opportunity is weakened by the existence of countries with low to non-existent corruption but large public sectors, like the Nordic countries.[47] These countries score high on the Ease of Doing Business Index, due to good and often simple regulations and have rule of law firmly established. Therefore, due to their lack of corruption in the first place, they can run large public sectors without inducing political corruption. Recent evidence that takes both the size of expenditures and regulatory complexity into account has found that high-income democracies with more expansive state sectors do indeed have higher levels of corruption.[4]

Like other governmental economic activities, also privatization, such as in the sale of government-owned property, is particularly at the risk of cronyism. Privatizations in Russia, Latin America, and East Germany were accompanied by large-scale corruption during the sale of the state-owned companies. Those with political connections unfairly gained large wealth, which has discredited privatization in these regions. While media have reported widely the grand corruption that accompanied the sales, studies have argued that in addition to increased operating efficiency, daily petty corruption is, or would be, larger without privatization and that corruption is more prevalent in non-privatized sectors. Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that extralegal and unofficial activities are more prevalent in countries that privatized less.[48]

In the European Union, the principle of subsidiarity is applied: a government service should be provided by the lowest, most local authority that can competently provide it. An effect is that distribution of funds in multiple instances discourages embezzlement because even small sums missing will be noticed. In contrast, in a centralized authority, even minute proportions of public funds can be large sums of money.

Governmental corruption

If the highest echelons of the governments also take advantage of corruption or embezzlement from the state's treasury, it is sometimes referred to the neologism kleptocracy. Members of the government can take advantage of the natural resources (e.g., diamonds and oil in a few prominent cases) or state-owned productive industries. A number of corrupt governments have enriched themselves via foreign aid. Indeed, there is a positive correlation between aid flows and high levels of corruption within recipient countries.[50][51]

Corruption in Sub-Saharan Africa consists primarily of extracting economic rent and moving the resulting financial capital overseas instead of investing at home. Authors Leonce Ndikumana and James K. Boyce estimate that from 1970 to 2008, capital flight from 33 sub-Saharan countries totalled $700 billion.[52]

A corrupt dictatorship typically results in many years of general hardship and suffering for the vast majority of citizens as civil society and the rule of law disintegrate. In addition, corrupt dictators routinely ignore economic and social problems in their quest to amass ever more wealth and power.

The classic case of a corrupt, exploitive dictator often given is the regime of Marshal Mobutu Sese Seko, who ruled the Democratic Republic of the Congo (which he renamed Zaire) from 1965 to 1997.[53] It is said that usage of the term kleptocracy gained popularity largely in response to a need to accurately describe Mobutu's regime. Another classic case is Nigeria, especially under the rule of General Sani Abacha who was de facto president of Nigeria from 1993 until his death in 1998. He is reputed to have stolen some US$3–4 billion. He and his relatives are often mentioned in Nigerian 419 letter scams claiming to offer vast fortunes for "help" in laundering his stolen "fortunes", which in reality turn out not to exist.[54] More than $400 billion was stolen from the treasury by Nigeria's leaders between 1960 and 1999.[55]

More recently, articles in various financial periodicals, most notably Forbes magazine, have pointed to Fidel Castro, General Secretary of the Republic of Cuba from 1959 until his death in 2016, of likely being the beneficiary of up to $900 million, based on "his control" of state-owned companies.[56] Opponents of his regime claim that he has used money amassed through weapons sales, narcotics, international loans, and confiscation of private property to enrich himself and his political cronies who hold his dictatorship together, and that the $900 million published by Forbes is merely a portion of his assets, although that needs to be proven.[57]

Judiciary corruption

There are two methods of corruption of the judiciary: the state (through budget planning and various privileges), and the private. Budget of the judiciary in many transitional and developing countries is almost completely controlled by the executive. The latter undermines the separation of powers, as it creates a critical financial dependence of the judiciary. The proper national wealth distribution including the government spending on the judiciary is subject of the constitutional economics.[58] Judicial corruption can be difficult to completely eradicate, even in developed countries.[59]

Opposing corruption

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anti-corruption. |

Mobile telecommunications and radio broadcasting help to fight corruption, especially in developing regions like Africa,[60] where other forms of communications are limited. In India, the anti-corruption bureau fights against corruption, and a new ombudsman bill called Jan Lokpal Bill is being prepared.

In the 1990s, initiatives were taken at an international level (in particular by the European Community, the Council of Europe, the OECD) to put a ban on corruption: in 1996, the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe,[61] for instance, adopted a comprehensive Programme of Action against Corruption and, subsequently, issued a series of anti-corruption standard-setting instruments:

- the Criminal Law Convention on Corruption (ETS 173);[25]

- the Civil Law Convention on Corruption (ETS 174);[26]

- the Additional Protocol to the Criminal Law Convention on Corruption (ETS 191);[62]

- the Twenty Guiding Principles for the Fight against Corruption (Resolution (97) 24);[63]

- the Recommendation on Codes of Conduct for Public Officials (Recommendation No. R (2000) 10);[64]

- the Recommendation on Common Rules against Corruption in the Funding of Political Parties and Electoral Campaigns (Rec(2003)4)[65]

The purpose of these instruments was to address the various forms of corruption (involving the public sector, the private sector, the financing of political activities, etc.) whether they had a strictly domestic or also a transnational dimension. To monitor the implementation at national level of the requirements and principles provided in those texts, a monitoring mechanism – the Group of States Against Corruption (also known as GRECO) (French: Groupe d'Etats contre la corruption) was created.

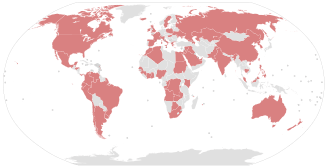

Further conventions were adopted at the regional level under the aegis of the Organization of American States (OAS or OEA), the African Union, and in 2003, at the universal level under that of the United Nations Convention against Corruption where it is enabled with mutual legal assistance between the states parties regarding investigations, processes and judicial actions related to corruption crimes, as established in article 46.

Whistleblowers

_(2).jpg)

A whistleblower (also written as whistle-blower or whistle blower) is a person who exposes any kind of information or activity that is deemed illegal, unethical, or not correct within an organization that is either private or public. The information of alleged wrongdoing can be classified in many ways: violation of company policy/rules, law, regulation, or threat to public interest/national security, as well as fraud, and corruption. Those who become whistleblowers can choose to bring information or allegations to the surface either internally or externally. Internally, a whistleblower can bring his/her accusations to the attention of other people within the accused organization such as an immediate supervisor. Externally, a whistleblower can bring allegations to light by contacting a third party outside of an accused organization such as the media, government, law enforcement, or those who are concerned. Whistleblowers, however, take the risk of facing stiff reprisal and retaliation from those who are accused or alleged of wrongdoing.

Because of this, a number of laws exist to protect whistleblowers. Some third-party groups even offer protection to whistleblowers, but that protection can only go so far. Whistleblowers face legal action, criminal charges, social stigma, and termination from any position, office, or job. Two other classifications of whistleblowing are private and public. The classifications relate to the type of organizations someone chooses to whistle-blow on private sector, or public sector. Depending on many factors, both can have varying results. However, whistleblowing in the public sector organization is more likely to result in criminal charges and possible custodial sentences. A whistleblower who chooses to accuse a private sector organization or agency is more likely to face termination and legal and civil charges.

Deeper questions and theories of whistleblowing and why people choose to do so can be studied through an ethical approach. Whistleblowing is a topic of ongoing ethical debate. Leading arguments in the ideological camp that whistleblowing is ethical to maintain that whistleblowing is a form of civil disobedience, and aims to protect the public from government wrongdoing. In the opposite camp, some see whistleblowing as unethical for breaching confidentiality, especially in industries that handle sensitive client or patient information. Legal protection can also be granted to protect whistleblowers, but that protection is subject to many stipulations. Hundreds of laws grant protection to whistleblowers, but stipulations can easily cloud that protection and leave whistleblowers vulnerable to retaliation and legal trouble. However, the decision and action have become far more complicated with recent advancements in technology and communication. Whistleblowers frequently face reprisal, sometimes at the hands of the organization or group they have accused, sometimes from related organizations, and sometimes under law. Questions about the legitimacy of whistleblowing, the moral responsibility of whistleblowing, and the appraisal of the institutions of whistleblowing are part of the field of political ethics.

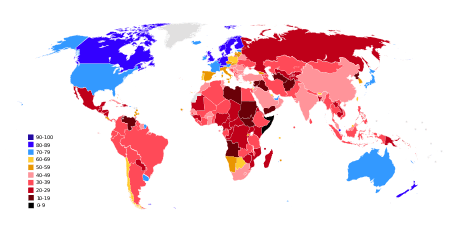

Measuring corruption

Measuring corruption accurately is difficult if not impossible due to the illicit nature of the transaction and imprecise definitions of corruption.[66] Few reliable measures of the magnitude of corruption exists and among those, there is a high level of heterogeneity. One of the most common ways to estimate corruption is through perception surveys. They have the advantage of good coverage, however, they do not measure corruption precisely.[7] While "corruption" indices first appeared in 1995 with the Corruption Perceptions Index CPI, all of these metrics address different proxies for corruption, such as public perceptions of the extent of the problem.[67] However, over time the refinement of methods and validation checks against objective indicators has meant that, while not perfect, many of these indicators are getting better at consistently and validly measuring the scale of corruption.[68]

Transparency International, an anti-corruption NGO, pioneered this field with the CPI, first released in 1995. This work is often credited with breaking a taboo and forcing the issue of corruption into high-level development policy discourse. Transparency International currently publishes three measures, updated annually: a CPI (based on aggregating third-party polling of public perceptions of how corrupt different countries are); a Global Corruption Barometer (based on a survey of general public attitudes toward and experience of corruption); and a Bribe Payers Index, looking at the willingness of foreign firms to pay bribes. The Corruption Perceptions Index is the best known of these metrics, though it has drawn much criticism[67][69][70] and may be declining in influence.[71] In 2013 Transparency International published a report on the "Government Defence Anti-corruption Index". This index evaluates the risk of corruption in countries' military sector.[72]

The World Bank collects a range of data on corruption,[73] including survey responses from over 100,000 firms worldwide[74] and a set of indicators of governance and institutional quality.[75] Moreover, one of the six dimensions of governance measured by the Worldwide Governance Indicators is Control of Corruption, which is defined as "the extent to which power is exercised for private gain, including both petty and grand forms of corruption, as well as 'capture' of the state by elites and private interests."[76] While the definition itself is fairly precise, the data aggregated into the Worldwide Governance Indicators is based on any available polling: questions range from "is corruption a serious problem?" to measures of public access to information, and not consistent across countries. Despite these weaknesses, the global coverage of these datasets has led to their widespread adoption, most notably by the Millennium Challenge Corporation.[66]

A number of parties have collected survey data, from the public and from experts, to try to gauge the level of corruption and bribery, as well as its impact on political and economic outcomes.[5][6] A second wave of corruption metrics has been created by Global Integrity, the International Budget Partnership,[77] and many lesser known local groups. These metrics include the Global Integrity Index,[78] first published in 2004. These second wave projects aim to create policy change by identifying resources more effectively and creating checklists toward incremental reform. Global Integrity and the International Budget Partnership[79] each dispense with public surveys and instead uses in-country experts to evaluate "the opposite of corruption" – which Global Integrity defines as the public policies that prevent, discourage, or expose corruption.[80] These approaches complement the first wave, awareness-raising tools by giving governments facing public outcry a checklist which measures concrete steps toward improved governance.[66]

Typical second wave corruption metrics do not offer the worldwide coverage found in first wave projects and instead focus on localizing information gathered to specific problems and creating deep, "unpackable" content that matches quantitative and qualitative data.

Alternative approaches, such as the British aid agency's Drivers of Change research, skips numbers and promotes understanding corruption via political economy analysis of who controls power in a given society.[66]

Institutions dealing with political corruption

- Global Witness, an international NGO established in 1993 that works to break the links between natural resource exploitation, conflict, poverty, corruption, and human rights abuses worldwide

- Group of States Against Corruption, a body established under the Council of Europe to monitor the implementation of instruments adopted by member states to combat political corruption

- Independent Commission Against Corruption (disambiguation)

- International Anti-Corruption Academy

- Transparency International, a non-governmental organization that monitors and publicizes corporate and political corruption in international development

- Corruption Perceptions Index, published yearly by Transparency International

- FreedomGuard, Ltd., a United States public benefit authority empowered to identify, investigate, and civilly prosecute federal & state government corruption

In fiction

The following are examples of works of fiction that portray political corruption in various forms.

- The Government Inspector – 1836 play by Nikolai Gogol[81]

- Democracy – 1880 novel by Henry Adams[82]

- The Financier – 1912 novel by Theodore Dreiser[83][84]

- The Titan – 1914 novel by Theodore Dreiser, sequel to The Financier[85][84]

- Washington Merry-Go-Round – 1932 film directed by James Cruze[86]

- Mr. Smith Goes to Washington – 1939 film directed by Frank Capra[87]

- Animal Farm – 1945 novel by George Orwell[88]

- All the King's Men – 1946 novel by Robert Penn Warren[89]

- The Stoic – 1947 novel by Theodore Dreiser, sequel to The Titan[84]

- Atlas Shrugged – 1957 novel by Ayn Rand[90]

- Touch of Evil – 1958 film directed by Orson Welles[91]

- Gumapang Ka Sa Lusak – 1990 film directed by Lino Brocka[92]

- Sa Kabila ng Lahat – 1990 film directed by Lino Brocka

- Sick Puppy – 2000 novel by Carl Hiaasen[93]

- Exit Wounds – 2001 film directed by Andrzej Bartkowiak

- American Gangster – 2007 film directed by Ridley Scott

- Guru – 2007 film directed by Mani Ratnam[94]

- House of Cards – 2013-18 web television series created by Beau Willimon[95]

See also

- List of anti-corruption agencies

- Baksheesh

- Comitology

- Conflict of interest

- Corruption

- Due diligence

- Government failure

- Influence peddling

- Index of Economic Freedom

- ISO 37001 Anti-bribery management systems

- Malfeasance in office

- Pay to play

- Policy laundering

- Political class

- Political correctness

- Political corruption in the United States

- Political machine

- Principal–agent problem

- Regulatory capture

- Tax evasion

- Big government

- Global Witness

- Group of States Against Corruption

- International Anti-Corruption Academy

- International Anti-Corruption Day

- United Nations Convention against Corruption

- Transparency International

- Gerrymandering

References

- Tanzi, Vito (1998-12-01). "Corruption Around the World: Causes, Consequences, Scope, and Cures". Staff Papers. 45 (4): 559–594. doi:10.2307/3867585. ISSN 0020-8027. JSTOR 3867585.

- Thompson, Dennis. Ethics in Congress: From Individual to Institutional Corruption (Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press, 1995). ISBN 0-8157-8423-6

- "African corruption 'on the wane'". 10 July 2007 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- Hamilton, Alexander (2013). "Small is beautiful, at least in high-income democracies: the distribution of policy-making responsibility, electoral accountability, and incentives for rent extraction" (PDF). World Bank.

- Hamilton, A. and Hudson, J. (2014) The Tribes that Bind: Attitudes to the Tribe and Tribal Leader in the Sudan. Bath Economic Research Papers 31/14. Archived 2015-02-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Hamilton, A. and Hudson, J. (2014) Bribery and Identity: Evidence from Sudan. Bath Economic Research Papers 30/14. Archived 2015-02-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Olken, Benjamin A.; Pande, Rohini (2012). "Corruption in Developing Countries" (PDF). Annual Review of Economics. 4: 479–509. doi:10.1146/annurev-economics-080511-110917. hdl:1721.1/73081.

- Luis Flores Ballesteros, "Corruption and development. Does the "rule of law" factor weigh more than we think?" Archived 2016-01-02 at the Wayback Machine 54 Pesos (November 15, 2008). Retrieved April 12, 2011

- Fisman, Raymond; Svensson, Jakob (2007). "Are corruption and taxation really harmful to growth? Firm level evidence". Journal of Development Economics. 83 (1): 63–75. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.18.32. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2005.09.009.

- "Corruption and growth in African countries: Exploring the investment channel, lead author Mina Baliamoune-Lutz, Department of Economics" (PDF). University of North Florida. p. 1,2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-09. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- "Nigeria's corruption busters". Unodc.org. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- "When the money goes west". New Statesman. 2005-03-14. Archived from the original on July 6, 2008. Retrieved 2009-11-05.

- Garrett, Laurie (2007). "The Challenge of Global Health". Foreign Affairs. 86 (1): 14–38. JSTOR 20032209.

- "Will Growth Slow Corruption In India?". Forbes. 2007-08-15.

- Sheeter, Laura (2007-11-24). "Ukraine remembers famine horror". BBC News. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- Sarah Bailey (2008) Need and greed: corruption risks, perceptions and prevention in humanitarian assistance Overseas Development Institute

- Perrin, Pierre (30 June 1998). "The impact of humanitarian aid on conflict development - ICRC". www.icrc.org.

- Nazim, Habibov (March 2016). "Effect of corruption on healthcare satisfaction in post-soviet nations". Social Science & Medicine. 152: 119–124. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.01.044. PMID 26854622.

- Borcan, Oana (February 2017). "Fighting corruption in education". American Economic Journal. 9: 180–209.

- Altbach, Philiph (2015). "The Question of Corruption". International Higher Education. 34.

- Heyneman, Stephen (2015). "The corruption of ethics in higher education". International Higher Education. 62.

- Fidelman, Charlie (November 27, 2010). "Cash bribes put patients atop surgery waiting lists". The Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 2011-01-21.

- Osipian, Ararat (2009-09-22). "Education Corruption, Reform, and Growth: Case of Post-Soviet Russia". Munich Personal RePEc Archive. Munich University Library. Retrieved 2016-05-21.

- "How common is bribe-paying?". Archived from the original on April 5, 2012.

...a relatively high proportion of families in a group of Central Eastern European, African, and Latin American countries paid a bribe in the previous twelve months.

- "Criminal Law Convention on Corruption: CETS No. 173". Conventions.coe.int. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- "Criminal Law Convention on Corruption: CETS No. 174". Conventions.coe.int. Retrieved 2012-12-01.

- Gallagher, Tom (2012-08-09). "The EU Can't Ignore Its Romania Problem". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2012-08-10.

- Carty, R. K. (1944). Party and Parish Pump: Electoral Politics in Ireland. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 9780889201057.

- O´Conaire, L. (2010). Thinking Aloud; A Spark Can Destroy a Forest. Paragon Publishing. ISBN 9781907611162.

- Shanklin, E. (1994). "Life Underneath the Market". In Chang, C.; Koster, H. A. (eds.). Pastoralists at the Periphery: Herders in a Capitalist World. University of Arizona.

- Bresnihan, V. (1997). "Aspects of Irish Political Culture; A Hermeneutical Perspective". In Carver, T.; Hyvarinen, M. (eds.). Interpreting the Political: New Methodologies. Routledge.

- Patricia OToole Sunday, Jun. 25, 2006 (2006-06-25). "The War of 1912". Time.com. Retrieved 2009-12-05.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Roosevelt, Theodore. An Autobiography: XV. The Peace of Righteousness, Appendix B, New York: Macmillan, 1913". Bartleby.com. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- "OCCRP announces 2015 Organized Crime and Corruption ‘Person of the Year’ Award". Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project.

- "AsiaMedia :: Right to Information Act India's magic wand against corruption". Asiamedia.ucla.edu. 2006-08-31. Archived from the original on 2008-09-26. Retrieved 2009-11-05.

- "Investigative journalists as anti-corruption activists: An interview with Gerardo Reyes". Transparency.org. 2013-06-07. Retrieved 2016-03-30.

- Mathiason, Nick (2007-01-21). "Western bankers and lawyers 'rob Africa of $150bn every year". London: Observer.guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- "Why benchmarking works – PSD Blog – World Bank Group". Psdblog.worldbank.org. 2006-08-17. Archived from the original on 2009-09-20. Retrieved 2009-11-05.

- Damania, Richard; Bulte, Erwin (July 2003). "Resources for Sale: Corruption, Democracy and the Natural Resource Curse" (PDF). Centre for International Economic Studies, University of Adelaide. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-09-06. Retrieved 2010-12-11.

- Soutik Biswas (2011-01-18). "Is India sliding into a hereditary monarchy?". BBC. BBC News. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- Deo, Manjeet; Kripalani (2011-08-05). "The Gandhi dynasty: Politics as usual". Rediff. Rediff News. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- Brunetti, Aymo; Weder, Beatrice (2003). "A free press is bad news for corruption". Journal of Public Economics. 87 (7–8): 1801–1824. doi:10.1016/s0047-2727(01)00186-4.

- Adserà, Alícia; ; Payne, Mark (2000). "Are You Being Served?: Political Accountability and Quality of Government" (PDF). Working Paper (438). Retrieved 2014-08-17. and Adserà, Alícia; ; Payne, Mark (2003). "Are You Being Served? Political Accountability and Quality of Government" (PDF). Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization. 19 (2): 445–490. doi:10.1093/jleo/19.2.445. hdl:10419/87999. Retrieved 2014-08-31.

- Snyder, James M.; Strömberg, David (2010). "Press Coverage and Political Accountability". Journal of Political Economy. 118 (2): 355–408. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.210.8371. doi:10.1086/652903.

- Schulhofer-Wohl, Sam; Garrido, Miguel (2013). "Do Newspapers Matter? Short-Run and Long-Run Evidence From the Closure of The Cincinnati Post" (PDF). Journal of Media Economics. 26 (2): 60–81. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.193.9046. doi:10.1080/08997764.2013.785553.

- Starr, Paul (2012). "An Unexpected Crisis: The News Media in Post-industrial Democracies" (PDF). International Journal of Press/Politics. 17 (2): 234–242. doi:10.1177/1940161211434422. Retrieved 2014-08-31.

Since 2000, the newspaper industry alone has lost an estimated "$1.6 billion in annual reporting and editing capacity... or roughly 30 per cent," but the new non-profit money coming into journalism has made up less than one-tenth that amount.

- "Lessons From the North". Project Syndicate. 2006-04-21. Retrieved 2009-11-05.

- Privatization in Competitive Sectors: The Record to Date. Sunita Kikeri and John Nellis. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 2860, June 2002. Econ.Chula.ac.th artimort.pdf IDEI.fr] Archived March 25, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Nick Davies (May 7, 2016). "The $10bn question: what happened to the Marcos millions?". The Guardian.

- Svensson, Jakob (2000). "Foreign Aid and Rent-Seeking". Journal of International Economics. 51 (2): 437–461. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.195.5516. doi:10.1016/S0022-1996(99)00014-8.

- Alesina, Alberto; Weder, Beatrice (2002). "Do Corrupt Governments Receive less Foreign Aid?". American Economic Review. 92 (4): 1126–1137. doi:10.1257/00028280260344669.

- "Should Africa challenge its "odious debts?"". Reuters. 15 March 2012.

- "How US nurtured dictators to Africa's detriment". Independent Online. 2 November 2018.

- Who wants to be a millionaire? – An online collection of Nigerian scam mails

- "Nigeria's corruption totals $400 billion". Malaysia Today. June 27, 2005. Archived from the original on 2007-12-11.

- "Fidel Castro net worth rises, according to 'Forbes'". Usatoday.Com. 2006-05-04. Retrieved 2009-11-05.

- Shapiro, Ben (2006-08-05). "Ben Shapiro :: Townhall.com :: The death of Fidel Castro". Townhall.com. Retrieved 2009-11-05.

- Barenboim, Peter (October 2009). Defining the rules. Issue 90. The European Lawyer.

- Pahis, Stratos (2009). "Corruption in Our Courts: What It Looks Like and Where It Is Hidden". The Yale Law Journal. 118. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "Mobile Phones and Radios Combat Corruption in Burundi – Voices from Emerging Markets". Voicesfromemergingmarkets.com. 2009-03-12. Archived from the original on 2009-06-30. Retrieved 2009-11-05.

- "Committee of Ministers – Home". Coe.int. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- "Additional Protocol to the Criminal Law Convention on Corruption: CETS No. 191". Conventions.coe.int. Retrieved 2012-12-01.

- "Council of Europe: Resolution (97) 24: On the Twenty Guiding Principles for the Fight Against Corruption" (PDF). Coe.int. Retrieved 2012-12-01.

- "Recommendation No. R (2000) 10 of the Committee of Ministers to Member States on Codes of Conduct for Public Officials" (PDF). Coe.int. Retrieved 2012-12-01.

- "Recommendation No. R (2003) 4 of the Committee of Ministers to Member States on Common Rules against Corruption" (PDF). Coe.int. Retrieved 2012-12-01.

- "A Users' Guide to Measuring Corruption". Global Integrity. September 5, 2008. Archived from the original on January 31, 2011. Retrieved 2010-12-11.

- Galtung, Fredrik (2006). "Measuring the Immeasurable: Boundaries and Functions of (Macro) Corruption Indices," in Measuring Corruption, Charles Sampford, Arthur Shacklock, Carmel Connors, and Fredrik Galtung, Eds. (Ashgate): 101–130.

- Hamilton, Alexander (2017). "Can We Measure the Power of the Grabbing Hand? A Comparative Analysis of Different Indicators of Corruption" (PDF). World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series.

- Sik, Endre (2002). "The Bad, the Worse and the Worst: Guesstimating the Level of Corruption". In Kotkin, Stephen; Sajo, Andras (eds.). Political Corruption in Transition: A Skeptic's Handbook. Budapest: Central European University Press. pp. 91–113. ISBN 978-963-9241-46-6.

- Arndt, Christiane and Charles Oman (2006). Uses and Abuses of Governance Indicators (Paris: OECD Development Centre).

- "Media citing Transparency International". Google Trends. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- Mark Pyman (March 2013). "Transparency is feasible". dandc.eu.

- "WBI Governance & Anti-Corruption – Data". Worldbank.org. Retrieved 2012-12-01.

- "Corruption – World Bank Survey of Business Managers". Enterprisesurveys.org. Retrieved 2012-12-01.

- "Public Sector Governance – Indicators of Governance & Institutional Quality". Go.worldbank.org. 2009-12-30. Archived from the original on 2012-01-10. Retrieved 2012-12-01.

- "A Decade of Measuring the Quality of Governance" (PDF). The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, The World Bank. 2007. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-27.

- "Home - International Budget Partnership". International Budget Partnership.

- "The Global Integrity Report | Global Integrity". Report.globalintegrity.org. Archived from the original on 2008-03-08. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- "International Budget Partnership". Internationalbudget.org. 2012-05-28. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- "The Global Integrity Report: 2009 Methodology White Paper". Global Integrity. 2009. Archived from the original on 2011-03-07. Retrieved 2010-12-11.

- Gallaher, Rachel (October 31, 2017). "Just Let Me Laugh at 'The Government Inspector'". City Arts Magazine. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- Meacham, Jon (September 11, 2018). "Henry Adams's 1880 Novel, 'Democracy,' Resonates Now More Than Ever". New York Times. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

It is a reflection on corruption within the political class, but, read carefully, it also reinforces an ancient view that those who are disgusted with republican government need to remember that the fault, as Cassius in Shakespeare’s “Julius Caesar” remarked, lies not in the stars, but in ourselves.

- Frum, David. "The Financier". FrumForum. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

Cowperwood had to build his fortune in a world in which interest rates of 10% and 15% were very commonplace things, and not just because people were poor and money was scarce. Capital was expensive because business was so non-transparent. Companies disclosed only what they wished to disclose, and investors demanded compensation for the huge risk that nasty surprises might be concealed in company books. Cowperwood’s solution? He discovers and puts to his own use the corrupt practices of the city government of Philadelphia, described by Lincoln Steffens as perhaps the worst governed big city in late 19th century America. Cowperwood strikes a deal with the city treasurer: the treasurer will lend him money from the city treasury at nominal rates – and with this money, Cowperwood will build fortunes for them both.

- Lingeman, Richard. "The Titan". American Heritage (Feb. / March 1993). Retrieved March 3, 2019.

But he did write more, including his monumental trilogy The Financier , The Titan , and The Stoic , in which he traced the rise of finance capitalism and its corruption of municipal government through the career of the predatory transit magnate Frank Cowperwood (based on the streetcar king Charles Tyson Yerkes).

- Frum, David. "The Titan". FrumForum. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

So Cowperwood invents a brilliant plan. He will not seek a renewal for himself. Instead, he has secret political associates launch an anti-Cowperwood campaign! They will demand that streetcar monopolists like Cowperwood be regulated by a new Public Utility Commission. The Commission will set rates, approve routes, and generally protect the public from the likes of Frank Cowperwood. Of course, the advocates of the commission acknowledge that the regulated companies will need some compensation for this new public vigilance. So they propose a compromise: in exchange for accepting the commission, all city franchises will be extended by 50 years. The commission proposal is advanced in the Illinois legislature, a body even more corrupt if possible than the Chicago city council. Dreiser minutely describes the protocol of corruption – how a bribe is asked, how it is offered, how it is paid, how much a vote goes for.

- Arnold, Jeremy. "Washington Merry-Go-Round". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

The title was certainly fresh enough in the public discourse to tell audiences that the film would probably address political corruption. Columbia Pictures bought the rights to the title and commissioned a fictional story of Congressman Button Gwinnett Brown, who draws the ire of his crooked colleagues to the extent that they trump up a recount to try and unseat him.

- "washingtonpost.com: 'Mr. Smith Goes to Washington'". www.washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 2019-02-01.

But this film caused quite a stir in this town in 1939. The Washington Press Club sponsored a premiere at Constitution Hall that was attended by congressmen, Senators and Supreme Court justices. About halfway through the film, people started walking out. At another dinner, Capra was criticized for showing graft in the Senate. The Washington press corps, who didn't like the way reporters were portrayed, joined in the attacks against Capra.

- Garton Ash, Timothy (October 30, 2001). "Why Orwell Matters". Hoover Digest. 2001 (4). Retrieved March 3, 2019.

Animal Farm is a timeless satire on the central tragi-comedy of all politics – that is, the tragi-comedy of corruption by power.

- "'All the King's Men,' Now 70, Has a Touch of 2016". Retrieved 2018-09-11.

- "Ayn Rand". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

Atlas Shrugged offers a complex and compelling depiction of the economic, political, and moral corruption spawned by “cronyism” between government and business.

- Malcolm, Derek (7 January 1999). "Orson Welles: A Touch of Evil". The Guardian. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

...it was generally underrated by the American critics of the time, who saw in it merely an eccentric thriller rather than a calculatedly dramatic study of the corruption of power and the difference between morality and justice.

- "Charo Santos and her triumphant return to film in Lav Diaz's 'Ang Babaeng Humayo'". cnn. Retrieved 2018-09-11.

- Hynes, James (1 February 2000). "Carl Hiaasen, Sick Puppy". Boston Review. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- Webster, Andy (January 15, 2007). "Polyester and Power at Play for a Mogul and His India". New York Times. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- Staples, Louis (7 November 2018). "The House of Cards ending summed up everything abhorrent about 2018". New Statesman. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

House of Cards displayed the corruption of America’s institutions and the elites who manipulate them as they become intoxicated by the pursuit of power, money and status. But amongst the backstabbing and political games, the cleverest thing about the show was the fact that its main characters – Francis and Claire Underwood – were merciless and evil, but also likeable.

Further reading

- Peter Bratsis. (2003) "The Construction of Corruption; or, Rules of Separation and Illusions of Purity in Bourgeois Societies", Social Text.

- Peter Bratsis. (2014) "Political Corruption in the Age of Transnational Capitalism: From the Relative Autonomy of the State to the White Man's Burden", Historical Materialism.

- Garifullin Ramil Ramzievich (2012) Bribe-taking mania as one of the causes of bribery. The concept of psychological and psychotherapeutic approaches to the problem of bribery and bribe-taking mania. J. Aktualnye Problemy Ekonomiki i Prava ("Current Problems in Economics and Law"), no. 4(24), pp. 9-15

- Michael W. Collier. (2009) Political Corruption in the Caribbean Basin: Constructing a Theory to Combat Corruption excerpt and text search

- Charles Copeman and Amy McGrath (eds.)(1997), Corrupt Elections. Ballot Rigging in Australia, Towerhouse Publications, Kensington, NSW

- Donatella della Porta, and Alberto Vannucci, (1999). Corrupt Exchanges: Actors, Resources, and Mechanisms of Political Corruption. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

- Axel Dreher, Christos Kotsogiannis, Steve McCorriston (2004), Corruption Around the World: Evidence from a Structural Model.

- Kimberly Ann Elliott, (ed.) (1997) Corruption and the Global Economy

- Robert M. Entman (2012) Scandal and Silence: Media Responses to Presidential Misconduct (Polity Press) 269 pages; case studies from USA 1998 to 2008 indicate the news media neglects many more incidents of corruption than it covers.

- Edward L. Glaeser and Claudia Goldin, (eds.) (2006), Corruption and Reform: Lessons from America's Economic History U. of Chicago Press, 386 pp. ISBN 0-226-29957-0.

- Mark Grossman. Political Corruption in America: An Encyclopedia of Scandals, Power, and Greed (2 vol. 2008)

- Arnold J. Heidenheimer, Michael Johnston and Victor T. LeVine (eds.) (1989), Political Corruption: A Handbook 1017 pages.

- Richard Jensen. (2001) "Democracy, Republicanism and Efficiency: The Values of American Politics, 1885–1930," in Byron Shafer and Anthony Badger, eds, Contesting Democracy: Substance and Structure in American Political History, 1775–2000 pp 149–180; online edition

- Michael Johnston, Victor T. LeVine, and Arnold Heidenheimer, eds. (1970) Political Corruption: Readings in Comparative Analysis

- Michael Johnston (2005), Syndromes of Corruption: Wealth, Power, and Democracy

- Junichi Kawata. (2006) Comparing Political Corruption And Clientelism excerpt and text search

- George C. Kohn (2001). The New Encyclopedia of American Scandal

- Johann Graf Lambsdorff (2007), The Institutional Economics of Corruption and Reform: Theory, Evidence and Policy Cambridge University Press

- Amy McGrath, (1994), The Forging of Votes, Tower House Publications, Kensington, NSW

- Amy McGrath, (2003), Frauding of Elections, Tower House Publications and H.S. Chapman Society, Brighton-le Sands, NSW

- Amy McGrath, (1994), The Frauding of Votes, Tower House Publications, Kensington, NSW

- Amy McGrath, (2005), The Stolen Election, Australia 1987 According to Frank Hardy, Author of Power Without Glory, Towerhouse Publications and H.S. Chapman Society, Brighton-le Sands, NSW

- John Mukum Mbaku. (1999) Bureaucratic and Political Corruption in Africa: The Public Choice Perspective

- Stephen D. Morris. (2009) Political Corruption in Mexico: The Impact of Democratization

- Aaron G. Murphy. (2010) Foreign Corrupt Practices Act: A Practical Resource for Managers and Executives

- Peter John Perry. (2002) Political Corruption in Australia: A Very Wicked Place?

- John F. Reynolds. (1988). Testing Democracy: Electoral Behavior and Progressive Reform in New Jersey, 1880–1920 on corrupt voting methods

- Robert North Roberts. (2001) Ethics in U.S. Government: An Encyclopedia of Investigations, Scandals, Reforms, and Legislation

- Susan Rose-Ackerman, (1999) Corruption and Government: Causes, Consequences, and Reform excerpt & text search

- Susan Rose-Ackerman, ed. (2011) International Handbook on the Economics of Corruption – Volume 2 excerpt and text search

- Susan Rose-Ackerman. (1978) Corruption: a study in political economy

- James C. Scott. (1972) Comparative Political Corruption

- Pietro Semeraro,(2008) Trading in influence and Lobbying in the Spanish Criminal Code

- Zephyr Teachout. Corruption in America: From Benjamin Franklin's Snuff Box to Citizens United (2014)

- Dennis Thompson. (1995) Ethics in Congress: From Individual to Institutional Corruption, Brookings Institution Press, Washington DC. ISBN 0-8157-8423-6

- Mark Wahlgren Summers. (1993) The Era of Good Stealings, corruption in American politics 1868–1877

- Darrell M. West (2000), Checkbook Democracy. How Money Corrupts Political Campaigns, Northeastern University Press, Boston (Mass.) ISBN 1-55553-440-6

- Woodward, C. Vann, ed. Responses of the Presidents to Charges of Misconduct (1975), American presidents from Washington to Lyndon Johnson

- Alexandra Wrage (2007) Bribery and Extortion: Undermining Business, Governments and Security

- Kim Hyoung-Kook (2012) : The Pre-conditions for entrenching transparency in local governance, a policy report of master's course in Public Administration from the University of York

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Corruption |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Political corruption. |

- UNODC – United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime – on corruption

- UNODC corruption campaign – Your NO counts!

- Global Integrity Report – local reporting and scorecards on anti-corruption performance in 90+ countries

- World Bank's Worldwide Governance Indicators Worldwide ratings of country performances on six governance dimensions from 1996 to present.

- SamuelGriffith.org.au, McGrath, Amy. Chapter Seven "One Vote, One Value: Electoral Fraud in Australia". Proceedings of the Eighth Conference of The Samuel Griffith Society.

- Reducing corruption in public governance : Rhetoric to reality

- Prevention: An Effective Tool to Reduce Corruption

- Reducing corruption at the local level

- Corrupt Cities : A Practical Guide to Cure and Prevention (162 pages)

- The Pre-conditions for Entrenching Transparency in Local Governance