14 July Revolution

The 14 July Revolution, also known as the 1958 Iraqi coup d'état, took place on 14 July 1958 in Iraq, and resulted in the overthrow of the Hashemite monarchy in Iraq that had been established by King Faisal I in 1921 under the auspices of the British. King Faisal II, Prince 'Abd al-Ilah, and Prime Minister Nuri al-Said were killed during the uprising.

| 14 July Revolution | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Arab Cold War | |||||||

Abdul Salam Arif and Abd al-Karim Qasim, the leaders of the revolution | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Prime Minister of Iraq |

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 15,000 troops | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

| |||||||

As a result of the overthrow of the Iraqi Hashemite dynasty, the coup d'état established the Iraqi Republic. The coup ended the Hashemite Arab Federation between Iraq and Jordan that had been established just 6 months earlier. Abd al-Karim Qasim took power as Prime Minister until 1963, when he was overthrown and killed in the Ramadan Revolution.

Pre-coup grievances

Regional disturbances

During World War II, Iraq was home to a growing number of Arab nationalists. They aimed, in part, to remove British imperial influence in Iraq.[2] This sentiment grew from a politicised educational system in Iraq and an increasingly assertive and educated middle class.[3] Schools served as instruments to internalise Pan-Arab nationalist identity as the leaders and the designers of the Iraqi educational system in the 1920s and 1930s were Pan-Arab nationalists who made a significant contribution to the expansion of that ideology in Iraq as well as the rest of the Arab world.[3] The two directors of the educational system in Iraq, Sami Shawkat and Fadhil al-Jamal, employed teachers who were political refugees from Palestine and Syria.[3] These exiles fled to Iraq because of their roles in anti-British and anti-French protests, and subsequently fostered Arab nationalist consciousness in their Iraqi students.[3] The growing general awareness of Arab identity led to anti-imperialism.

Similarly, Pan-Arab sentiment grew across the Arab world and was promoted by Egypt's Gamel Abdel Nasser, a rising politician and staunch opponent of imperialism. Hashemite Iraq faced and confronted these sentiments as well. Nuri al-Said, the Iraqi Prime Minister, was interested in pursuing the idea of a federation of Arab States of the Fertile Crescent, but was less enthusiastic about a Pan-Arab state. Al-Said brought Iraq into the Arab League in 1944, seeing it as a forum for bringing together the Arab states while leaving the door open for a possible future federation.[4] The League's charter enshrined the principle of autonomy for each Arab state and referenced pan-Arabism only rhetorically.

Economic climate

The Iraqi economy fell into a recession and then a depression following World War II; inflation was uncontrolled and the Iraqi standard of living fell.[5] Al-Said and the Arab Nationalist regent, Abd al-Ilah, were continually in opposition to each other, failing to agree on a cohesive economic policy, infrastructure improvements, or other internal reforms.[5]

In 1950, al-Said persuaded the Iraqi Petroleum Company to increase the royalties paid to the Iraqi government. Al-Said looked to Iraq's growing oil revenues to fund and propel development.[6] He determined that 70 percent of Iraq's revenue from oil was to be set aside for infrastructure development by a Development Board with three foreign advisors out of six total members. This foreign presence provoked popular disapproval of al-Said's policy.[7] Despite anti-Western sentiments toward oil and development, al-Said hired economist Arthur Salter to investigate the prospects for development in Iraq because al-Said's oil revenue reallocation seemed to be ineffective.[8] Salter continued to make suggestions[9] as to how to implement development projects despite massive Iraqi dislike of his presence.

Political grievances

During World War II, the British reoccupied Iraq and in 1947, through the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty of 1948 (also known as the Portsmouth Treaty) on 15 January, Salih Jabr negotiated British withdrawal from Iraq. This agreement included a joint British and Iraqi joint defence board to oversee Iraqi military planning, and the British continued to control Iraqi foreign affairs.[10] Iraq was still tied to Great Britain for military supplies and training. This treaty was to last until 1973—a 25-year period that Arab nationalists in Iraq could not accept.[11] As a strong reaction to the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty of 1948, Arab nationalists led the Wathbah Rebellion a year later in protest of the continued British presence in Iraq.[8] Al-Said repudiated the Portsmouth Treaty to appease the rebellious Iraqi and Arab nationalists.[8]

In 1955, Iraq entered into the Baghdad Pact with Iran, Pakistan, and Turkey. The pact was a defence agreement between the four nations and was endorsed by the UK and the United States as an anti-communist Cold War strategy, but was greatly resented by Iraqis in general.[12] Egypt saw the Baghdad Pact as a provocation and a challenge to its regional dominance. In 1956, when Egypt nationalised the Suez Canal, Iraqi-Egyptian relations were further strained. When British, French and Israelis invaded Egypt, Iraq, as a British ally, had to support the invasion.[12] The fact that imperial ties dragged Iraq into supporting this invasion of Arab lands led to wide disapproval across the Iraqi populace, which largely sympathised with Egypt and responded to pan-Arab ideology. They felt that the invasion of Egypt was another sign of Western aggression and dominance in the region.[12]

Similarly, when Egypt and Syria united to form the United Arab Republic (UAR) under the banner of pan-Arabism in 1958, Iraqi politicians found themselves in a vulnerable position. Iraqi leaders had no interest in uniting with Egypt and instead proposed and ratified their own pan-Arab union with Hashemite Jordan in May 1958.[12] Great Britain and the United States openly supported this union, but many Iraqis were suspicious of its purpose and regarded the Arab Union of Iraq and Jordan as another "tool of their Western overlord".[12]

Precursors

The primary goal of the coup was to liberate Iraq from its imperial ties with the British and the United States. The Western powers dominated all sectors of Iraqi governance: national politics and reform, regional politics with its Arab and non-Arab neighbours, and economic policies. As a general rule, many Iraqis were resentful of the presence of Western powers in the region, especially the British. Furthermore, Hashemite monarchic rule could not be divorced from the image of imperial masters behind the monarchy. The monarchy had struggled to maintain power during the Al-Wathbah uprising in 1948 and the Iraqi Intifada of 1952.

Discord mounts

A growing number of educated elites in Iraq were becoming enamoured with the ideals espoused by Nasser's pan-Arab movement. The ideas of qawmiyah found many willing adherents, particularly within the officer classes of the Iraqi military. Al-Said's policies were considered anathema by certain individuals within the Iraqi armed forces, and opposition groups began to form, modelled on the Egyptian Free Officers Movement that had overthrown the Egyptian monarchy in 1952.

Despite al-Said's efforts to quell growing unrest with the military ranks (such as economic programs designed to benefit the officer class, and brokering deals with the U.S. to supply the Iraqi military),[13] his position was significantly weakened by the events of the Suez Crisis. Al-Said suffered for his association with Britain; the latter's role in the Crisis seeming a damning indictment of his wataniyah policies[14] Despite al-Said's efforts to distance himself from the crisis, the damage was done to his position. Iraq became isolated within the Arab world, as highlighted by its exclusion from the "Treaty of Arab Solidarity" in January 1957.[15] The Suez Crisis benefited Nasser's pan-Arab cause while simultaneously undermining those Arab leaders who followed pro-Western policy. Al-Said's policies fell firmly within the latter camp, and covert opposition to his government steadily grew in the wake of Suez.

Building to a crisis

On 1 February 1958, Egypt and Syria boosted the pan-Arab movement immeasurably with the announcement that they had united as the United Arab Republic (UAR).[16] The move was a catalyst for a series of events that culminated in revolution in Iraq. The formation of the UAR and Nasser's lofty rhetoric calling for a united Arab world galvanised pan-Arabism in Iraq and Jordan. Their governments attempted something of a response with the creation of the Arab Federation on 14 February[17]—a union of the two states—but few were impressed by this knee-jerk reaction to the UAR.

The Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen (North Yemen) joined the UAR soon after its formation. Attention then shifted to Lebanon, where Syria sponsored the Arab nationalist movement in its civil war campaign against the pro-Western government of Camille Chamoun.[18] Al-Said recognised that Chamoun's defeat would leave Iraq and Jordan isolated. He bolstered Chamoun's government with aid throughout May and June 1958.[18] More fatefully he attempted to bolster Jordan with units from the Iraqi army, a move that was a direct catalyst for the coup d'état.

14 July revolution

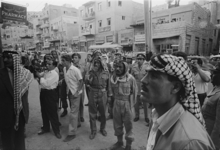

On 14 July 1958, a group that identified as the Free Officers, a secret military group led by Brigadier Abd al-Karim Qasim, overthrew the monarchy. This group was markedly Pan-Arab in character. King Faisal II, Prince Abd al-Ilah, and Nuri al-Said were all killed.[19]

The Free Officers were inspired by and modelled after the Egyptian Free Officers who overthrew the Egyptian Monarchy in 1952.[12] They represented all parties and cut across political factions.[20] Qasim was a member of the generation that had launched the revolution in Egypt, and had grown up in an era where radicalism and Pan-Arabism were circulating in schools, including high schools and military academies.[21] As a group, most of the Free Officers were Sunni Arabs who came from a modern middle class.[22] The Free Officers were inspired by a number of events in the Middle East the decade before 1952. The 1948 War against Israel was an experience that intensified the Egyptian Free Officers' sense of duty.[21] They understood their mission as deposing the corrupt regimes that weakened a unified Arab nation and thrown their countries into distress.[21] The success of the Free Officers in overthrowing the Egyptian monarchy and seizing power in 1952 made Nasser a source of inspiration too.[21]

The Iraqi Free Officer group was an underground organization and much of the planning and timing rested in the hands of Qasim and his associate, Colonel Abdul Salam Arif.[22] The Free Officers sought to ensure Nasser's support and the assistance of the UAR to implement the revolt because they feared the members of the Baghdad Pact would subsequently overthrow the Free Officers as a reaction to the coup.[21] Nasser only offered moral support, whose material significance remained vague, so Egypt had no practical role in the Iraqi revolution.[21]

The dispatching of Iraqi army units to Jordan played into the hands of two of the key members of the Iraqi Free Officers movement: Arif and the movement's leader, Qasim. The Iraqi 19th and 20th Brigades of the 3rd Division (Iraq) (the former under Qasim's command and the latter including Arif's battalion) were dispatched to march to Jordan, along a route that passed Baghdad. The opportunity for a coup was thus presented to and seized upon by the conspirators.

Arif marched on Baghdad with the 20th Brigade and seized control of the capital (with the help of Colonel Abd al-Latif al-Darraji) while Qasim remained in reserve with the 19th at Jalawla.[23]

In the early hours of 14 July, Arif seized control of Baghdad's broadcasting station, which was soon to become the coup's headquarters, and broadcast the first announcement of the revolution. Arif "denounced imperialism and the clique in office; proclaimed a new republic and the end of the old regime...announced a temporary sovereignty council of three members to assume the duties of the presidency; and promised a future election for a new president".[23]

Arif then dispatched two detachments from his regiment, one to al-Rahab Palace to deal with King Faisal II and the Crown Prince 'Abd al-Ilah, the other to Nuri al-Said's residence. Despite the presence of the crack Royal Guard at the Palace, no resistance was offered, by order of the Crown Prince. It is uncertain what orders were given to the palace detachment, and what level of force they detailed.

At approximately 8:00am the King, Crown Prince, Princess Hiyam ('Abd al-Ilah's wife), Princess Nafeesa ('Abd al-Ilah's mother), Princess Abadiya (Faisal's aunt), other members of the Iraqi Royal Family, and several servants were killed or wounded as they were leaving the palace.[24] Only Princess Hiyam survived although how and why she did is unclear. With their demise, the Iraqi Hashemite dynasty ended. Meanwhile, al-Said temporarily slipped the net of his would-be captors by escaping across the Tigris after being alerted by the sound of gunfire.

By noon, Qasim arrived in Baghdad with his forces and set up headquarters in the Ministry of Defence building. The conspirator's attention now shifted to finding al-Said, lest he escape and undermine the coup's early success. A reward of 10,000 Iraqi dinar was offered for his capture[25] and a large-scale search began. On 15 July he was spotted in a street in the al-Battawin quarter of Baghdad attempting to escape disguised in a woman's abaya.[26] Al-Said and his accomplice were both shot, and his body was buried in the cemetery at Bab al-Mu'azzam later that evening.[23]

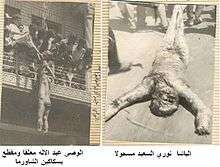

Mob violence continued even in the wake of al-Said's death. Spurred by Arif to liquidate traitors,[24] uncontrollable mobs took to the streets of Baghdad. The body of 'Abd al-Ilah was taken from the palace, mutilated and dragged through the streets, and finally hanged outside the Ministry of Defence. Several foreign nationals (including Jordanian and American citizens) staying at the Baghdad Hotel were killed by the mob. Mass mob violence did not die down until Qasim imposed a curfew, which still did not prevent the disinterment, mutilation and parading of Al-Said's corpse through the streets the day after its burial.[27]

Aftermath

Immediate effects

Abd al-Karim Qasim's sudden coup took the U.S. government by surprise. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Director Allen Dulles told President Dwight D. Eisenhower that he believed Nasser was behind it. Dulles also feared that a chain reaction would occur throughout the Middle East and that the governments of Iraq, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Iran would be doomed.[28] The Hashemite monarchy represented a reliable ally of the Western world in thwarting Soviet advances, so the coup compromised Washington's position in the Middle East.[28] Indeed, the Americans saw it in epidemiological terms.[29]

Qasim reaped the greatest reward, being named Prime Minister and Minister of Defence. Arif became Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of the Interior, and deputy Commander in Chief.[28]

Thirteen days after the revolution, a temporary constitution was announced, pending a permanent organic law to be promulgated after a free referendum. According to the document, Iraq was a republic and a part of the Arab nation and the official state religion was listed as Islam. Both the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies were abolished. Powers of legislation were vested in the Council of Ministers, with the approval of the Sovereignty Council; the executive function was also vested in the Council of Ministers.[28]

1959 instability

On 9 March 1959, The New York Times reported that the situation in Iraq was initially "confused and unstable, with rival groups competing for control. Cross currents of communism, Arab and Iraqi nationalism, anti-Westernism and the 'positive neutrality' of President Gamal Abdel Nasser of the United Arab Republic have been affecting the country."[30]

The new Iraqi Republic was headed by a Revolutionary Council.[31] At its head was a three-man sovereignty council, composed of members of Iraq's three main communal/ethnic groups. Muhammad Mahdi Kubbah represented the Shi'a population; Khalid al-Naqshabandi, the Kurds; and Najib al Rubay’i, the Sunni population.[32] This tripartite Council assumed the role of the Presidency. A cabinet was created, composed of a broad spectrum of Iraqi political movements, including two National Democratic Party representatives, one member of al-Istiqlal, one Ba'ath representative and one Marxist.[32]

By March 1959, Iraq withdrew from the Baghdad Pact and created alliances with left-leaning countries and communist countries, including the Soviet Union.[33] Because of their agreement with the USSR, Qasim's government allowed the formation of an Iraqi Communist Party.[33]

Human rights violations and mass exodus

Kanan Makiya compared the trials of political dissidents under the Iraqi monarchy, Qasim's government, and Ba'athist Iraq, concluding: "A progressive degradation in the quality of each spectacle is evident."[34]

The 1958 military coup that overthrew the Hashemite monarchy brought to power members of "rural groups that lacked the cosmopolitan thinking found among Iraqi elites". Iraq's new leaders had an "exclusivist mentality [that] produced tribal conflict and rivalry, which in turn called forth internal oppression [...]"[35]

According to Shafeeq N. Ghabra, a professor of political science at Kuwait University, and, in 2001, director of the Kuwait Information Office in Washington D.C.:[35]

- After the 1958 revolution, Iraq's ruling establishment created a state devoid of political compromise. Its leaders liquidated those holding opposing views, confiscated property without notice, trumped up charges against its enemies, and fought battles with imaginary domestic foes. This state of affairs reinforced an absolute leader and a militarized Iraqi society totally different from the one that existed during the monarchy.

Hundreds of thousands of Iraqis fled the country within four years of the 1958 revolution.[35]

See also

References

Notes

- Romero 2011, p. 112.

- Hunt 2005, p. 72.

- Eppel 1998, p. 233.

- Tripp 2007, p. 115.

- Hunt 2005, p. 73.

- Tripp 2007, p. 124.

- Tripp 2007, p. 125.

- Tripp 2007, p. 134.

- Salter, A., and S. W. Payton. The development of Iraq; a plan of action by Lord Salter, assisted by S.W. Payton. 1955. London: Caxton, for the Iraq Development Board

- Eppel 2004, p. 74.

- Tripp 2007, p. 117.

- Hunt 2005, p. 75.

- Hunt 2005, p. 108.

- Hunt 2005, p. 109; Barnett 1998, p. 127.

- Barnett 1998, p. 128.

- Barnett 1998, p. 129.

- Barnett 1998, p. 131.

- Simons 2003, pp. 249–51.

- Tripp 2007, p. 142.

- Tripp 2007, p. 142; Hunt 2005, p. 76.

- Eppel 2004, p. 151.

- Eppel 2004, p. 152.

- Marr 2003, p. 156.

- Marr 2003, p. ?.

- Marr 2003, p. 157.

- Simons 2003, p. 252.

- Simons 2003, p. 252: "At first he [Said] was buried in a shallow grave but later the body was dug up and repeatedly run over by municipal buses, 'until, in the words of a horror-struck eyewitness, it resembled bastourma, an Iraqi [pressed] sausage meat'."

- Mufti 2003, p. 173.

- As in Kuwait for example: "The situation in Kuwait is very shaky as a result of the coup in Iraq, and there is a strong possibility that the revolutionary infection will spread there." See Keefer, Edward C.; LaFantasie, Glenn W., eds. (1993). "Special National Intelligence Estimate: The Middle East Crisis. Washington, July 22, 1958". Foreign Relations of the United States, 1958–1960, Volume XII: Near East Region; Iraq; Iran; Arabian Peninsula. Washington, DC: Department of State. p. 90.

The frantic Anglo-American reaction to the developments in Iraq, which Allen Dulles asserted was "primarily a UK responsibility", makes for an interesting read, beginning here.

- Hailey, Foster (9 March 1959). "Iraqi Army Units Opposing Kassim Rebel in Oil Area". The New York Times. L3.

- Simons 2003, p. 220

- Marr 2003, p. 158.

- Hunt 2005, p. 76.

- Makiya, Kanan (1998). Republic of Fear: The Politics of Modern Iraq, Updated Edition. University of California Press. pp. 50–51. ISBN 9780520921245.

- Ghabra, Shafeeq N., "Iraq's Culture of Violence", article in Middle East Quarterly, Summer 2001, accessed 16 October 2013; in a footnote at the end of the first sentence ("... political compromise."), Ghabra cites Sa‘d al-Bazzaz, Ramad al-Hurub: Asrar ma Ba‘d Hurub al-Khalij, 2d ed. (Beirut: al-Mu'assasa al-Ahliya li'n-Nashr wa't-Tawzi‘, 1995), p. 22.

Bibliography

- Barnett, Michael N. (1998). Dialogues in Arab Politics: Negotiations in Regional Order. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-10918-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eppel, Michael (1998). "The Elite, the Effendiyya, and the Growth of Nationalism and Pan-Arabism in Hashemite Iraq, 1921–1958". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 30 (2): 227–250. doi:10.1017/s0020743800065880. JSTOR 164701.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eppel, Michael (2004). Iraq from Monarchy to Tyranny: From the Hashemites to the Rise of Saddam. Tallahassee, FL: University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-2736-4.

- Farouk-Sluglett, Marion; Sluglett, Peter (1990). Iraq since 1958: From Revolution to Dictatorship. London & New York, NY: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-85043-317-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) 3rd edition published in 2003.

- Hunt, Courtney (2005). The History of Iraq. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-33414-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marr, Phebe (2003). The Modern History of Iraq (2nd ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mufti, Malik (2003). "The United States and Nasserist Pan-Arabism". In David W. Lesch, ed., The Middle East and the United States: A Historical and Political Reassessment (4th ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press. pp. 168–187. ISBN 978-0813343495.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Romero, Juan (2011). The Iraqi Revolution of 1958: A Revolutionary Quest for Unity and Security. Lanham, MD: University Press of America. ISBN 978-0761852582.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Simons, Geoff (2003). Iraq: From Sumer to Post-Saddam. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1403917706.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tripp, Charles (2007). A History of Iraq (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521702478.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Choueiri, Youssef M.; Arab Nationalism: A History Blackwell 2000

- Cleveland, William L.; A History of the Modern Middle East Westview Press 1994

- Dawisha, Adeed: Arab Nationalism in the Twentieth Century: From Triumph to Despair Princeton University Press 2003

- Kedourie, Elie; Politics in the Middle East Oxford University Press 1997

- Lewis, Roger and Owen, Roger (editors); A Revolutionary Year: The Middle East in 1958 I.B. Tauris 2002

- Polk, William R.; Understanding Iraq I.B. Tauris 2006

- Watry, David M. Diplomacy at the Brink: Eisenhower, Churchill, and Eden in the Cold War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2014.

External links

- "Revolt in Baghdad". Time Magazine. 21 July 1958. Retrieved 27 July 2009.

- "In One Swift Hour". Time Magazine. 28 July 1958. Retrieved 27 July 2009.