Jean-Charles Pichegru

Jean-Charles Pichegru (16 February 1761 – 5 April 1804) was a distinguished French general of the Revolutionary Wars. Under his command, French troops overran Belgium and the Netherlands before fighting on the Rhine front. His royalist positions led to his loss of power and imprisonment in Cayenne, French Guiana during the Coup of 18 Fructidor in 1797. After escaping into exile in London and joining the staff of Alexander Korsakov, he returned to France and planned the Pichegru Conspiracy to remove Napoleon from power, which led to his arrest and death. Despite his defection, his surname is one of the names inscribed under the Arc de Triomphe, on Column 3.

Jean-Charles Pichegru | |

|---|---|

Commander-in-Chief, Army of the Rhine | |

| Born | 16 February 1761 Arbois or Les Planches-près-Arbois |

| Died | 5 April 1804 (aged 43) Paris |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1783–1797 |

| Rank | Divisional general |

| Battles/wars | French Revolutionary Wars |

Early life and career

Pichegru was born in a peasant family at Arbois (or, according to Charles Nodier, at Les Planches-près-Arbois, near Lons-le-Saulnier), in the then Franche-Comté (now in the Jura department of France). The friars of Arbois were entrusted with his education, and sent him to the military school of Brienne-le-Château. There, he taught mathematics, and among his pupils was the young Napoleon Bonaparte. In 1783, he entered the 1st regiment of artillery, where he rapidly rose to the rank of adjutant-second lieutenant, and briefly served in the American Revolutionary War.

When the Revolution erupted in 1789, he became leader of the Jacobin Club in Besançon, and, when a regiment of volunteers of the départment of the Gard marched through the city, he was elected lieutenant colonel.

Rhine front

The fine condition of his regiment was noticed in the French Revolutionary Army section of the Rhine, and his organizing ability got him appointed in the headquarters, and then promoted général de brigade.

In 1793, Lazare Carnot and Louis de Saint-Just were sent to find roturier (non-aristocratic) generals who could prove successful (see: Campaigns of 1793 in the French Revolutionary Wars). Carnot discovered Jean-Baptiste Jourdan, and Saint-Just discovered Louis Lazare Hoche and Pichegru. At first, Pichegru was appointed général de division and commander of the Division of the Upper Rhine.

Appointed commander-in-chief of the Army of the Rhine, Pichegru attacked the Coalition army of Dagobert Sigmund von Wurmser in the Battle of Haguenau in 1793. Over a period of weeks the Coalition Forces were driven back step by step in bitter fighting. The intervention of the Army of the Moselle under Hoche at the Battle of Froeschwiller in late December finally caused Wurmser to abandon Alsace. For the Second Battle of Wissembourg, Pichegru was placed under the command of Hoche, who proved to be a difficult superior. Nevertheless, the French again won the battle, compelling Wurmser to retreat to the east bank of the Rhine and the Prussian army to withdraw toward Mainz.

Northern front

In December 1793, Hoche was arrested, probably owing to his colleague's denunciations, and Pichegru became commander-in-chief of the Army of the Rhine and Moselle. He was summoned to succeed Jourdan in the Army of the North in February 1794, subsequently fighting three major campaigns within the year. The forces of the Kingdom of Great Britain, the Dutch Republic and Habsburg Austria held a strong position along the Sambre to the North Sea.

After attempting to break the Austrian centre, Pichegru suddenly turned their right, and defeated the Count of Clerfayt at Cassel, Menin and Courtrai, while his subordinate, Joseph Souham, defeated Prince Josias of Coburg in the battle of Tourcoing in May 1794. After a lull, during which Pichegru feigned a siege of Ypres, he again attacked Clerfayt, and defeated him at Roeselare and Hooglede, while Jourdan, commanding the newly named Army of Sambre-et-Meuse, withstood Austrian attacks in the battle of Fleurus (27 June 1794), which eventually led to Allied evacuation of the Low Countries.

Pichegru began his second campaign by crossing the Meuse on 18 October, and, after taking Nijmegen, drove the Austrians beyond the Rhine. The Anglo-Hanoverian army withdrew behind the Waal. Then, while Pichegru's troops prepared to go into winter quarters, the Convention ordered the Army of the North to mount a winter campaign. On 27 December two brigades crossed the Meuse on the ice, and stormed the Bommelerwaard. On 10 January Pichegru's army crossed the ice of the Waal between Zaltbommel and Nijmegen, then, on 13 January, entered Utrecht, which surrendered on the 16th. The Anglo-Hanoverian army retreated behind the IJssel and then withdrew to Hanover and Bremen. Pichegru, who had successfully penetrated the frozen Hollandic Water Line, arrived in Amsterdam on 20 January, after the Batavian Revolution had taken place. The French occupied the rest of the Dutch Republic in the next month.

This major victory was marked by unique episodes, such as the Capture of the Dutch fleet at Den Helder by French hussars, and exceptional discipline of the French battalions in Amsterdam, who, although faced with the opportunity of plundering the richest city in Europe, showed self-restraint.

Thermidor and Directory

Although a former associate of Saint-Just, Pichegru offered his services to the Thermidorian Reaction, and, after having received the title of Sauveur de la Patrie ("Saviour of the Fatherland") from the National Convention, subdued the sans-culottes of Paris, when they rose in insurrection against the Convention on 12 Germinal (1 April).

Pichegru then took command of the armies of the North, the Sambre-and-Meuse, and the Rhine, and, crossing the Rhine in force, took Mannheim in May 1795.

Going over to the Royalists

Although he had become a hero of the Revolution, he allowed his colleague Jourdan to be defeated, betrayed all his plans to the enemy, and took part in organizing a conspiracy for the return and crowning of Louis XVIII as King of France. The plans were suspected, and, when he offered his resignation to the Directory in October 1795, it was promptly accepted (much to his surprise). He retired in disgrace, but secured his election to the Council of Five Hundred in May 1797 as a leader of the Royalists.

Coup attempts and death

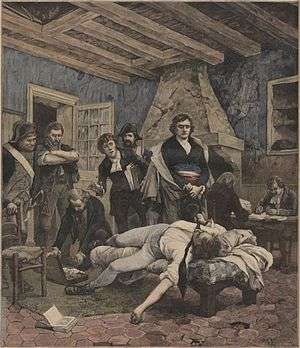

Pichegru planned a coup d'état during the Coup of 18 Fructidor, but he was arrested and with fourteen others was deported to Cayenne, French Guiana in 1797. He and seven others escaped and fled to Paramaribo. The gouverneur De Friderici allowed them to get on board a ship to the United States. Shortly thereafter, he went to London where he joined thousands of Frenchmen who had left France in a mass movement in an effort to save themselves from the violence of the French Revolution. There, he served on General Aleksandr Rimsky-Korsakov's staff in the campaign of 1799. He went to Paris in August 1803 with Georges Cadoudal to head a royalist uprising against the First Consul, Napoleon Bonaparte. Betrayed by a friend, Pichegru was arrested on 28 February 1804, and was later found strangled in prison on the morning of April 6. The government reported that he had committed suicide, but Napoleon has been regularly blamed for orchestrating the murder.[1][2] However, there is little evidence that Napoleon was involved. His supporters often argue that Napoleon had nothing to gain from having Pichegru murdered, especially after the execution of d'Enghein, which infuriated the royalty across Europe. [3]

Pichegru was buried in the cimetière Sainte-Catherine, a Paris cemetery with its entrance in the former rue de Fer, and which was closed in 1824.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles Pichegru. |

- Scott, Sir Walter (1827). The Life of Napoleon Bonaparte, Emperor of the French. 2. New York: J. & J. Harper. pp. 49–50.

- "Pichegru".

- Roberts, Andrew (2014). Napoleon: A Life. Penguin. p. 419.

Sources

- Alan Schom, Napoleon Bonaparte

- Louis Fauche-Borel, Mémoires

- J.M. Gassier, Vie du général Pichegru, Paris, 1815

- Comte de Montgaillard, Mémoires concernant la trahison de Pichegru, 1804

- G. Pierret, Pichegru, son prods et sa mon, 1826

- Anne Jean Marie René Savary, Mémoires sur la mort de Pichegru, Paris, 1825