Crisis of the Third Century

The Crisis of the Third Century, also known as Military Anarchy or the Imperial Crisis (235–284 AD), was a period in which the Roman Empire nearly collapsed under the combined pressures of barbarian invasions and migrations into the Roman territory, civil wars, peasant rebellions, political instability (with multiple usurpers competing for power), Roman reliance on (and growing influence of) barbarian mercenaries known as foederati and commanders nominally working for Rome (but increasingly independent), plague, debasement of currency, and economic depression.

The crisis began with the assassination of Emperor Severus Alexander by his own troops in 235. This initiated a 50-year period during which there were at least 26 claimants to the title of emperor, mostly prominent Roman army generals, who assumed imperial power over all or part of the Empire. The same number of men became accepted by the Roman Senate as emperor during this period and so became legitimate emperors.

By 268, the empire had split into three competing states: the Gallic Empire (including the Roman provinces of Gaul, Britannia and, briefly, Hispania); the Palmyrene Empire (including the eastern provinces of Syria Palaestina and Aegyptus); and, between them, the Italian-centered independent Roman Empire proper. Later, Aurelian (270–275) reunited the empire. The crisis ended with the ascension of Diocletian and his implementation of reforms in 284.

The crisis resulted in such profound changes in the empire's institutions, society, economic life, and religion that it is increasingly seen by most historians as defining the transition between the historical periods of classical antiquity and late antiquity.[1]

History

| Roman imperial dynasties | |||

| Crisis of the Third Century | |||

| Chronology | |||

| Barracks Emperors | 235–284 | ||

| Gordian dynasty | 238–244 | ||

| Valerian dynasty | 253–261 | ||

| Gallic Emperors | 260–274 | ||

| Illyrian Emperors | 268–284 | ||

| Caran dynasty | 282–285 | ||

| Britannic Emperors | 286–297 | ||

| Succession | |||

| Preceded by Severan dynasty |

Followed by Diocletian and the Tetrarchy | ||

After the Roman Empire had been stabilized, once again, after the turmoil of the Year of the Five Emperors (193) in the reign of Septimius Severus, the later Severan dynasty lost more and more control.

The army required larger and larger bribes to remain loyal.[2] Septimius Severus raised the pay of legionaries, and gave substantial donativum to the troops.[3][4] The large and ongoing increase in military expenditure caused problems for all of his successors.[5] His son Caracalla raised the annual pay and lavished many benefits on the army in accordance with the advice of his father to keep their loyalty,[6][7][8] and considered dividing the Empire into eastern and western sectors with his brother Geta to reduce the conflict in their co-rule.[9]

The situation of the Roman Empire became dire in 235. Many Roman legions had been defeated during a previous campaign against Germanic peoples raiding across the borders, while the emperor Severus Alexander had been focused primarily on the dangers from the Sassanid Empire. Leading his troops personally, the emperor resorted to diplomacy and accepting tribute to pacify the Germanic chieftains quickly, rather than military conquest. According to Herodian this cost Severus Alexander the respect of his troops, who may have felt that more severe punishment was required for the tribes that had intruded on Rome's territory.[10] The troops assassinated Severus Alexander and proclaimed the new emperor to be Maximinus Thrax, commander of one of the legions present.

Maximinus was the first of the barracks emperors – rulers who were elevated by the troops without having any political experience, a supporting faction, distinguished ancestors, or a hereditary claim to the imperial throne. As their rule rested on military might and generalship, they operated as warlords reliant on the army to maintain power. Maximinus continued the campaigns in Germania but struggled to exert his authority over the whole empire. The Senate was displeased at having to accept a peasant as Emperor.[11] This precipitated the chaotic Year of the Six Emperors during which all of the original claimants were killed: in 238 a revolt broke out in Africa led by Gordian I and Gordian II,[12] which was soon supported by the Roman Senate,[13] but this was quickly defeated with Gordian II killed and Gordian I committing suicide. The Senate, fearing Imperial wrath,[14] raised two of their own as co-Emperors, Pupienus and Balbinus with Gordian I's grandson Gordian III as Caesar.[15] Maximinus marched on Rome but was assassinated by his Legio II Parthica, and subsequently Pupienus and Balbinus were murdered by the Praetorian Guard.

In the following years, numerous generals of the Roman army fought each other for control of the empire and neglected their duties of defending it from invasion. There were frequent raids across the Rhine and Danube frontier by foreign tribes, including the Carpians, Goths, Vandals, and Alamanni, and attacks from Sassanids in the east. Climate changes and a sea level rise disrupted the agriculture of what is now the Low Countries, forcing tribes residing in the region to migrate into Roman lands.[16] Further disruption arose in 251, when the Plague of Cyprian (possibly smallpox) broke out. This plague caused large-scale death, severely weakening the empire.[17][18] The situation was worsened in 260 when the emperor Valerian was captured in battle by the Sassanids (he later died in captivity).

Throughout the period, numerous usurpers claimed the imperial throne. In the absence of a strong central authority, the empire broke into three competing states. The Roman provinces of Gaul, Britain, and Hispania broke off to form the Gallic Empire in 260. The eastern provinces of Syria, Palestine, and Aegyptus also became independent as the Palmyrene Empire in 267. The remaining provinces, centered on Italy, stayed under a single ruler but now faced threats on every side.

An invasion of Macedonia and Greece by Goths, who had been displaced from their lands on the Black Sea, was defeated by emperor Claudius II Gothicus at the Battle of Naissus in 268 or 269. Historians see this victory as the turning point of the crisis. In its aftermath, a series of tough, energetic barracks emperors were able to reassert central authority. Further victories by Claudius Gothicus drove back the Alamanni and recovered Hispania from the Gallic Empire. He died of the plague in 270 and was succeeded by Aurelian, who had commanded the cavalry at Naissus. Aurelian reigned (270–275) through the worst of the crisis, gradually restoring the empire. He defeated the Vandals, Visigoths, Palmyrene Empire, and finally the remainder of the Gallic Empire. By late 274, the Roman Empire had been reunited into a single entity. However, Aurelian was assassinated in 275, sparking a further series of competing emperors with short reigns. The situation didn't stabilize until Diocletian, himself a barracks emperor, took power in 284.

More than a century would pass before Rome again lost military ascendancy over its external enemies. However, dozens of formerly thriving cities, especially in the Western Empire, had been ruined. Their populations dead or dispersed, these cities could not be rebuilt, due to the economic breakdown caused by constant warfare. The economy had been ruined by the breakdown in trading networks and the debasement of the currency. Major cities and towns, including Rome itself, had not needed fortifications for many centuries, but now surrounded themselves with thick walls.

Fundamental problems with the empire still remained. The right of imperial succession had never been clearly defined, which was a factor in the continuous civil wars as competing factions in the military, Senate, and other parties put forward their favored candidate for emperor. The sheer size of the empire, which had been an issue since the late Roman Republic three centuries earlier, continued to make it difficult for a single ruler to effectively counter multiple threats at the same time. These continuing problems were addressed by the radical reforms of Diocletian, who broke the cycle of usurpation. He began by sharing his rule with a colleague, then formally established the Tetrarchy of four co-emperors in 293.[19] Historians regard this as the end of the crisis period, which had lasted 58 years. However the trend of civil war would continue after the abdication of Diocletian in the Civil wars of the Tetrarchy (306-324) until the rise of Constantine the Great as sole Emperor.[20] The empire survived until 476 in the West and until 1453 in the East.

Causes

The problem of succession and civil war

From the beginning of the Principate there were no clear rules for the imperial succession, largely because the empire maintained the facade of a republic.[21]

During the early Principate, the process for becoming an emperor relied on a combination of proclamation by the Senate, popular approval, and acceptance by the army, in particular the Praetorian Guard. A family connection to a previous emperor was beneficial, but it did not determine the issue in the way a formal system of hereditary succession would. From the Julio-Claudian dynasty onwards was sometimes tension between the Senate's preferred choice and the army. As the Senatorial class declined in political influence and more generals were recruited from the provinces this tension increased.

Whenever the succession appeared uncertain, there was an incentive for any general with support of a sizable army to attempt to seize power, sparking civil war. The most recent example of this prior to the Crisis was the Year of the Five Emperors which resulted in the victory of Septimius Severus. After the overthrow of the Severan dynasty, for the rest of the 3rd Century, Rome was ruled by a series of generals, coming into power through frequent civil wars which devastated the empire.[22]

Natural disasters

The first and most immediately disastrous of the natural disasters that the Roman Empire faced during the Third Century was the plague. The Antonine Plague that preceded the Crisis of the Third Century sapped manpower from Roman armies and proved disastrous for the Roman economy.[23] From 249 AD to 262 AD, the Plague of Cyprian devastated the Roman Empire so much so that some cities, such as the city of Alexandria, experienced a 62% decline in population. These plagues greatly hindered the Roman Empire's ability to ward off barbarian invasions but also factored into problems such as famine, with many farms becoming abandoned and unproductive.[24]

A second and longer-term natural disaster that took place during the Third Century was the increased variability of weather. Drier summers meant less agricultural productivity and more extreme weather events led to agricultural instability. This could also have contributed to the increased barbarian pressure on Roman borders, as they too would have experienced the detrimental effects of climate change and sought to push inward to more productive regions of the Mediterranean.[25]

Foreign invasions

Barbarian invasions came in the wake of civil war, plague, and famine. Distress caused in part by the changing climate led various barbarian tribes to push into Roman territory. Other tribes coalesced into more formidable entities (notably the Alamanni and Franks), or were pushed out of their former territories by more dangerous peoples such as the Sarmatians (the Huns did not appear west of the Volga for another century). Eventually, the frontiers were stabilized by the Illyrian Emperors. However, barbarian migrations into the empire continued in greater and greater numbers. Though these migrants were initially closely monitored and assimilated, later tribes eventually entered the Roman Empire en masse with their weapons, giving only token recognition of Roman authority.[26]

The defensive battles that Rome had to endure on the Danube since the 230s, however, paled in comparison to the threat the empire faced in the East. There, Sassanid Persia represented a far greater danger to Rome than the isolated attacks of Germanic tribes.[27] The Sassanids had in 224 and 226 overthrown the Parthian Arsacids, and the Persian King Ardashir I, who also wanted to prove his legitimacy through military successes, had already penetrated into Roman territory at the time of Severus Alexander, probably taking the strategically important cities of Nisibis and Carrhae.[28]

Economic impact

Internally, the empire faced hyperinflation caused by years of coinage devaluation.[29] This had started earlier under the Severan emperors who enlarged the army by one quarter,[30] and doubled the base pay of legionaries. As each of the short-lived emperors took power, they needed ways to raise money quickly to pay the military's "accession bonus" and the easiest way to do so was by inflating the coinage severely, a process made possible by debasing the coinage with bronze and copper.

This resulted in runaway rises in prices, and by the time Diocletian came to power, the old coinage of the Roman Empire had nearly collapsed. Some taxes were collected in kind and values often were notional, in bullion or bronze coinage. Real values continued to be figured in gold coinage, but the silver coin, the denarius, used for 300 years, was gone (1 pound of gold = 40 gold aurei = 1,000 denarii = 4,000 sestertii). This currency had almost no value by the end of the third century, and trade was carried out without retail coinage.

Breakdown of internal trade network

One of the most profound and lasting effects of the Crisis of the Third Century was the disruption of Rome's extensive internal trade network. Ever since the Pax Romana, starting with Augustus, the empire's economy had depended in large part on trade between Mediterranean ports and across the extensive road systems to the Empire's interior. Merchants could travel from one end of the empire to the other in relative safety within a few weeks, moving agricultural goods produced in the provinces to the cities, and manufactured goods produced by the great cities of the East to the more rural provinces.

Large estates produced cash crops for export and used the resulting revenues to import food and urban manufactured goods. This resulted in a great deal of economic interdependence among the empire's inhabitants. The historian Henry St. Lawrence Beaufort Moss describes the situation as it stood before the crisis:

Along these roads passed an ever-increasing traffic, not only of troops and officials but of traders, merchandise and even tourists. An interchange of goods between the various provinces rapidly developed, which soon reached a scale unprecedented in the previous history and not repeated until a few centuries ago. Metals mined in the uplands of Western Europe, hides, fleeces, and livestock from the pastoral districts of Britain, Spain, and the shores of the Black Sea, wine and oil from Provence and Aquitaine, timber, pitch and wax from South Russia and northern Anatolia, dried fruits from Syria, marble from the Aegean coasts, and – most important of all – grain from the wheat-growing districts of North Africa, Egypt, and the Danube Valley for the needs of the great cities; all these commodities, under the influence of a highly organized system of transport and marketing, moved freely from one corner of the Empire to the other.[31]

With the onset of the Crisis of the Third Century, however, this vast internal trade network broke down. The widespread civil unrest made it no longer safe for merchants to travel as they once had, and the financial crisis that struck made exchange very difficult with the debased currency. This produced profound changes that, in many ways, foreshadowed the very decentralized economic character of the coming Middle Ages.

Large landowners, no longer able to successfully export their crops over long distances, began producing food for subsistence and local barter. Rather than import manufactured goods from the empire's great urban areas, they began to manufacture many goods locally, often on their own estates, thus beginning the self-sufficient "house economy" that would become commonplace in later centuries, reaching its final form in the manorialism of the Middle Ages. The common, free people of the Roman cities, meanwhile, began to move out into the countryside in search of food and better protection.

Made desperate by economic necessity, many of these former city dwellers, as well as many small farmers, were forced to give up hard-earned basic civil rights in order to receive protection from large land-holders. In doing so, they became a half-free class of Roman citizen known as coloni. They were tied to the land, and in later Imperial law, their status was made hereditary. This provided an early model for serfdom, the origins of medieval feudal society and of the medieval peasantry.

However, although the burdens on the population increased, especially the lower strata of the population, this can not be generalized to the whole empire, especially since the living conditions were not uniform. Although the structural integrity of the economy suffered from the military conflicts of that time and the inflationary episode of the 270s, it did not collapse, especially because of the complex regional differences. Recent research has shown that there were regions that prospered even further, such as Egypt, Africa and Hispania. But even for Asia Minor, which was directly affected by attacks, no general decline can be observed.[32] While commerce and the economy flourished in several regions, with several provinces not affected by hostilities, other provinces experienced some serious problems, as evidenced by personal hoards in the northwestern provinces of the empire. However, there can be no talk of a general economic crisis throughout the whole of Empire.[33]

Increased localism

All the Barracks Emperors based their power on the military and on the soldiers of the field armies, not on the Praetorians in Rome. Thus, Rome lost its role as the political center of the empire during the third century, although it remained ideologically important. In order to legitimize and secure their rule, the emperors of the third century needed above all military successes.[34]

Even the Roman cities began to change in character. The large cities of classical antiquity slowly gave way to the smaller, walled cities that became common in the Middle Ages. These changes were not restricted to the third century, but took place slowly over a long period, and were punctuated with many temporary reversals. In spite of extensive reforms by later emperors, however, the Roman trade network was never able to fully recover to what it had been during the Pax Romana (27 BC-AD 180). This economic decline was far more noticeable and important in the western part of the empire, which was also invaded by barbarian tribes several times during the century. Hence, the balance of power clearly shifted eastward during this period, as evidenced by the choice of Diocletian to rule from Nicomedia in Asia Minor, putting his second in command, Maximian, in Milan. This would have a considerable impact on the later development of the empire with a richer, more stable eastern empire surviving the end of Roman rule in the west.

While imperial revenues fell, imperial expenses rose sharply. More soldiers, greater proportions of cavalry, and the ruinous expense of walling in cities all added to the toll. Goods and services previously paid for by the government were now demanded in addition to monetary taxes. The steady exodus of both rich and poor from the cities and now-unprofitable professions forced Diocletian to use compulsion; most trades were made hereditary, and workers could not legally leave their jobs or travel elsewhere to seek better-paying ones.

The decline in commerce between the imperial provinces put them on a path toward increased self-sufficiency. Large landowners, who had become more self-sufficient, became less mindful of Rome's central authority, particularly in the Western Empire, and were downright hostile toward its tax collectors. The measure of wealth at this time began to have less to do with wielding urban civil authority and more to do with controlling large agricultural estates in rural regions since this guaranteed access to the only economic resource of real value — agricultural land and the crops it produced. The common people of the empire lost economic and political status to the land-holding nobility, and the commercial middle classes waned along with their trade-derived livelihoods. The Crisis of the Third Century thus marked the beginning of a long gradual process that would transform the ancient world of Classical antiquity into the medieval one of the Early Middle Ages.

Emperors

Several emperors who rose to power through acclamation of their troops attempted to create stability by appointing their descendants as Caesar, resulting in several brief dynasties. These generally failed to maintain any form of coherence beyond one generation, although there were exceptions.

Gordian dynasty

| Portrait | Name | Birth | Succession | Reign | Death | Time in office |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gordian I CAESAR MARCVS ANTONIVS GORDIANVS SEMPRONIANVS AFRICANVS AVGVSTVS |

c. 159 AD, Phrygia? | Proclaimed emperor, whilst Pro-consul in Africa, during a revolt against Maximinus Thrax. Ruled jointly with his son Gordian II, and in opposition to Maximinus. Technically a usurper, but retrospectively legitimized by the accession of Gordian III | March 22, 238 AD – April 12, 238 AD | April 238 AD Committed suicide upon hearing of the death of Gordian II |

21 days |

|

Gordian II CAESAR MARCVS ANTONIVS GORDIANVS SEMPRONIANVS ROMANVS AFRICANVS AVGVSTVS |

c. 192 AD, ? | Proclaimed emperor, alongside father Gordian I, in opposition to Maximinus by act of the Senate | March 22, 238 AD – April 12, 238 AD | April 238 AD Killed during the Battle of Carthage, fighting a pro-Maximinus army |

21 days |

|

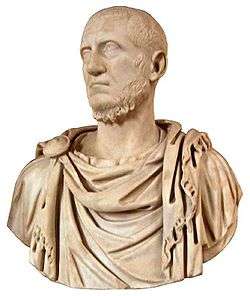

Pupienus (non-dynastic) CAESAR MARCVS CLODIVS PVPIENVS MAXIMVS AVGVSTVS |

c. 178 AD, ? | Proclaimed joint emperor with Balbinus by the Senate in opposition to Maximinus; later co-emperor with Balbinus | April 22, 238 AD – July 29, 238 AD | July 29, 238 AD Assassinated by the Praetorian Guard |

3 months and 7 days |

|

Balbinus (non-dynastic) CAESAR DECIMVS CAELIVS CALVINVS BALBINVS PIVS AVGVSTVS |

? | Proclaimed joint emperor with Pupienus by the Senate after death of Gordian I and II, in opposition to Maximinus; later co-emperor with Pupienus and Gordian III | April 22, 238 AD – July 29, 238 AD | July 29, 238 AD Assassinated by Praetorian Guard |

3 months and 7 days |

|

Gordian III CAESAR MARCVS ANTONIVS GORDIANVS AVGVSTVS |

January 20, 225 AD, Rome | Proclaimed emperor by supporters of Gordian I and II, then by the Senate; joint emperor with Pupienus and Balbinus until July 238 AD. Grandson of Gordian I | April 22, 238 AD – February 11, 244 AD | February 11, 244 AD Unknown; possibly murdered on orders of Philip I |

5 years, 9 months and 20 days |

|

Philip the Arab (non-dynastic) CAESAR MARCVS IVLIVS PHILIPPVS AVGVSTVS with Philip II MARCVS IVLIVS SEVERVS PHILLIPVS AVGVSTVS |

c. 204 AD, Shahba, Syria | Praetorian Prefect to Gordian III, took power after his death; made his son Philip II co-emperor in summer 247 AD | February 244 AD – September/October 249 AD | September/October 249 AD (aged 45) Killed in the Battle of Verona by Decius |

5 years |

Decian dynasty

| Portrait | Name | Birth | Succession | Reign | Death | Time in office |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.jpg) |

Trajan Decius CAESAR GAIVS MESSIVS QVINTVS TRAIANVS DECIVS AVGVSTVS with Herennius Etruscus |

c. 201 AD, Budalia, Pannonia Inferior | Governor under Philip I; proclaimed emperor by Danubian legions then defeating & killing Philip in the Battle of Verona; made his son Herennius Etruscus co-emperor in early 251 AD | September/ October 249 AD – June 251 AD | June 251 AD Both killed in the Battle of Abrittus fighting against the Goths |

2 years |

|

Hostilian CAESAR CAIVS VALENS HOSTILIANVS MESSIVS QVINTVS AVGVSTVS |

Sirmium | Son of Trajan Decius, accepted as heir by the Senate | June 251 AD – late 251 AD | September/October 251 AD Natural causes (plague) |

4–5 months |

|

Trebonianus Gallus (non-dynastic) CAESAR GAIVS VIBIVS TREBONIANVS GALLVS AVGVSTVS with Volusianus GAIVS VIBIVS VOLVSIANVS AVGVSTVS |

206 AD, Italia | Governor of Moesia Superior, proclaimed emperor by Danubian legions after Decius's death (and in opposition to Hostilian); made his son Volusianus co-emperor in late 251 AD. | June 251 AD – August 253 AD | August 253 AD (aged 47) Assassinated by their own troops, in favor of Aemilian |

2 years |

|

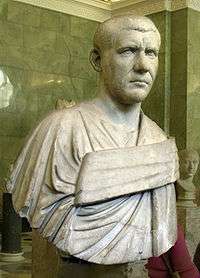

Aemilian (non-dynastic) CAESAR MARCVS AEMILIVS AEMILIANVS AVGVSTVS |

c. 207 or 213 AD Africa | Governor of Moesia Superior, proclaimed emperor by Danubian legions after defeating the Goths; accepted as emperor after death of Gallus | August 253 AD – October 253 AD | September/October 253 AD (aged 40 or 46) Assassinated by his own troops, in favor of Valerian |

2 months |

Valerian dynasty

| Portrait | Name | Birth | Succession | Reign | Death | Time in office |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valerian CAESAR PVBLIVS LICINIVS VALERIANVS AVGVSTVS |

c. 195 AD | Governor of Noricum and Raetia, proclaimed emperor by Rhine legions after death of Gallus; accepted as emperor after death of Aemilian | October 253 AD – 260 AD | After 260 AD Captured in Battle of Edessa against Persians, died in captivity |

7 years | |

|

Gallienus CAESAR PVBLIVS LICINIVS EGNATIVS GALLIENVS AVGVSTVS with Saloninus |

218 AD | Son of Valerian, made co-emperor in 253 AD; his son Saloninus is very briefly co-emperor in c. July 260 before assassination by Postumus | October 253 AD – September 268 AD | September 268 AD Murdered at Aquileia by his own commanders |

15 years |

Gordian dynasty continued ?

| Portrait | Name | Birth | Succession | Reign | Death | Time in office |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

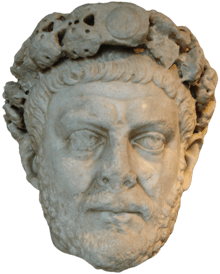

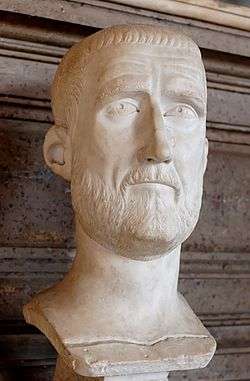

Claudius II CAESAR MARCVS AVRELIVS CLAVDIVS AVGVSTVS |

May 10, 210 AD, Sirmium | Victorious general at Battle of Naissus, seized power after Gallienus's death According to Epitome de Caesaribus He was a bastard son of Gordian II | September 268 AD – January 270 AD | January 270 AD (aged 60) Natural causes (plague) |

1 year, 4 months |

.jpg) |

Quintillus CAESAR MARCVS AVRELIVS CLAVDIVS QVINTILLVS AVGVSTVS |

c.210 AD, Sirmium | Brother of Claudius II, seized power after his death | January 270 AD – September(?) 270 AD | 270 AD (aged around 60) Unclear; possibly suicide or murder |

Unknown |

_and_182_(Siscia)-765588_(obverse).jpg) |

Aurelian (non-dynastic) CAESAR LVCIVS DOMITIVS AVRELIANVS AVGVSTVS |

September 9, 214 AD/215 AD, Sirmium | Proclaimed emperor by Danubian legions after Claudius II's death, in opposition to Quintillus | September(?) 270 AD – September 275 AD | September 275 AD (aged 60–61) Assassinated by Praetorian Guard |

5 years |

Tacitus

| Portrait | Name | Birth | Succession | Reign | Death | Time in office |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tacitus CAESAR MARCVS CLAVDIVS TACITVS AVGVSTVS |

c. 200, Interamna Nahars, Italia | Elected by the Senate to replace Aurelian, after a short interregnum | September 25, 275 AD – June 276 AD | June 276 AD (aged 76) Natural causes (possibly assassinated) |

9 months |

.jpg) |

Florianus CAESAR MARCVS ANNIVS FLORIANVS AVGVSTVS |

? | Brother of Tacitus, elected by the army in the west to replace him | June 276 AD – September? 276 AD | September? 276 AD (aged ?) Assassinated by his own troops, in favor of Probus |

3 months |

|

Probus (non-dynastic) CAESAR MARCVS AVRELIVS PROBVS AVGVSTVS |

232 AD, Sirmium | Governor of the eastern provinces, proclaimed emperor by Danubian legions in opposition to Florian | September? 276 AD – September/ October 282 AD | September/ October 282 AD (aged 50) Assassinated by his own troops, in favor of Carus |

6 years |

Caran dynasty

| Portrait | Name | Birth | Succession | Reign | Death | Time in office |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

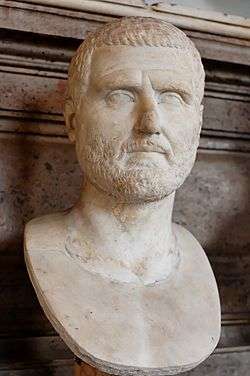

Carus CAESAR MARCVS AVRELIVS CARVS AVGVSTVS |

c. 230 AD, Narbo, Gallia Narbonensis | Praetorian Prefect to Probus; seized power either before or after Probus was murdered; made his son Carinus co-emperor in early 283 AD | September/ October 282 AD – late July/ early August 283 AD | Late July/early August 283 AD Natural causes? (Possibly killed by lightning) |

10–11 months |

|

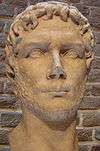

Numerian CAESAR MARCVS AVRELIVS NVMERIVS NVMERIANVS AVGVSTVS |

? | Son of Carus, succeeded him jointly with his brother Carinus | Late July/early August 283 AD – 284 AD? | 284 AD Unclear; possibly assassinated |

1 year |

| Carinus CAESAR MARCVS AVRELIVS CARINVS AVGVSTVS |

? | Son of Carus, ruled shortly with him and then with his brother Numerian | Early 283 AD – 285 AD | 285 AD Died in battle against Diocletian? |

2 years |

See also

- Bagaudae

- Sengoku period – a similar period in Japanese history

- Warring States period and Three Kingdoms period – similar periods in Chinese history

Notes

- Brown, Peter Robert Lamont (1971). The World of Late Antiquity. London: Thames and Hudson. p. 22. ISBN 978-0500320228.

- Potter, David Stone (2004). The Roman Empire at Bay, AD 180–395 Routledge history of the ancient world. Psychology Press. pp. 85, 167. ISBN 978-0415100588.

- "Septimius Severus:Legionary Denarius". Penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2019-05-10.

- Kenneth W. Harl, Coinage in the Roman Economy, 300 B.C. to A.D. 700, Part 700, p.216

- R.J. van der Spek, Lukas De Blois (2008), An Introduction to the Ancient World, page 272 Archived 2017-07-30 at the Wayback Machine, Routledge

- Grant, Michael (1996). The Severans: the Changed Roman Empire. Psychology Press. p. 42.

- Dunstan, William, E. (2011). Ancient Rome. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield. p. 405. ISBN 978-0-7425-6832-7.

- Boatwright, Mary Taliaferro; Gargola, Daniel J; Talbert, Richard J. A. (2004). The Romans, from village to empire. Oxford University Press. p. 413. ISBN 978-0-19-511875-9.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2009). How Rome Fell: death of a superpower. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-300-16426-8.

- " Herodian says "in their opinion, Alexander showed no honourable intention to pursue the war and preferred a life of ease, when he should have marched out to punish the Germans for their previous insolence" (Herodian vi.7.10).

- Southern, Pat The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine, Routledge, 2001, p. 64

- Southern, Pat The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine, Routledge, 2001, p. 66

- Joannes Zonaras, Compendium of History extract: Zonaras: Alexander Severus to Diocletian: 222–284 12:16

- Southern, Pat The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine, Routledge, 2001, p. 67

- Meckler, Michael L., Maximinus Thrax (235–238 A.D.), De Imperatoribus Romanis (1997)

- Southern, Pat (2011-02-17). "Third Century Crisis of the Roman Empire". BBC History, 17 February 2011. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/romans/thirdcenturycrisis_article_01.shtml.%5B%5D

- Zosimus (1814) [translation originally printed]. The New History, Book 1. (scanned and published online by Roger Pearse). London: Green and Chaplin. pp. 16, 21, 31. Retrieved 2016-04-22.

- Sherman, Irwin W. (2006). The power of plagues by Irwin W. Sherman. ISBN 9781555816483. Retrieved 2019-05-10.

- Kolb, Frank (1987). Diocletian und die Erste Tetrarchie. Improvisation oder Experiment in der Organisation monarchischer Herrschaft?, Berlin: de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-010934-4

- MacMullen, Ramsay. Constantine. New York: Dial Press, 1969. ISBN 0-7099-4685-6

- "Res Publica Restituta? Republic and Princeps in the Early Roman Empire – Armstrong Undergraduate Journal of History". www.armstrong.edu. Retrieved 2018-10-19.

- Freedman, Paul (Fall 2011). "The Crisis of the Third Century and the Diocletianic Reforms". Yale University. Archived from the original on 2017-12-08. Retrieved 2018-10-19.

- Sabbatani, S.; Fiorino, S. (December 2009). "The Antonine Plague and the decline of the Roman Empire". Le Infezioni in Medicina: Rivista Periodica di Eziologia, Epidemiologia, Diagnostica, Clinica e Terapia delle Patologie Infettive. 17 (4): 261–275. ISSN 1124-9390. PMID 20046111.

- Harper, Kyle (2017-11-01). "Solving the Mystery of an Ancient Roman Plague". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 2018-01-21. Retrieved 2018-10-20.

- Light, John A. (26 January 2011). "Was the Roman Empire a victim of climate change?". Need to Know. PBS. Archived from the original on 2018-10-20.

- Nigel., Rodgers (2006). Roman Empire. Dodge, Hazel. London: Lorenz Books. ISBN 978-0754816027. OCLC 62177842.

- Josef Wiesehöfer: Das Reich der Sāsāniden, in Klaus Peter Johne, Udo Hartmann, Thomas Gerhardt, Die Zeit der Soldatenkaiser: Krise und Transformation des Römischen Reiches im 3. Jahrhundert n. Chr. (235–284) 2008, p. 531ff.

- Erich Kettenhofen: Die Eroberung von Nisibis und Karrhai durch die Sāsāniden in der Zeit Kaiser Maximins, 235/236 AD. In: Iranica Antiqua 30 (1995), pp. 159–177

- "This infographic shows how currency debasement contributed to the fall of Rome". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 2017-10-11. Retrieved 2017-10-20.

- Flichy, Thomas. Financial crises and renewal of empires. Lulu.com. ISBN 9781291097337.

- Henry St. Lawrence Beaufort Moss (1935). The Birth of the Middle Ages 395–814. London: Oxford University Press. pp. 1.

- Ruffing, Kai (2006). Deleto paene imperio Romano: Transformationsprozesse des Römischen Reiches im 3. Jahrhundert und ihre Rezeption in der Neuzeit. Stuttgart: Steiner. p. 223. ISBN 978-3-515-08941-8. OCLC 180946164.

- Hekster, Olivier. (2008). Rome and its Empire, AD 193–284. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-7486-2992-3. OCLC 271165910.

- Johne, Klaus-Peter; Hartmann, Udo; Gerhardt, Thomas (2008). Die Zeit der Soldatenkaiser: Krise und Transformation des Römischen Reiches im 3. Jahrhundert n. Chr. (235–284). Rome: Akademie Verlag. p. 1026. ISBN 978-3050045290.

Bibliography

- Allen, Larry (2009). The Encyclopedia of Money (2nd ed.). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. pp. 346–348. ISBN 978-1598842517.

- Davies, Glyn (1997) [1994]. A History of Money: From Ancient Times to the Present Day (Reprint ed.). Cardiff: University of Wales Press. pp. 95–99. ISBN 978-0708313510.

- Olivier Hekster, Rome and its Empire, AD 193–284 (Edinburgh 2008) ISBN 978 0 7486 2303 7

- Klaus-Peter Johne (ed.), Die Zeit der Soldatenkaiser (Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2008).

- Alaric Watson, Aurelian and the Third Century (Taylor & Francis, 2004) ISBN 0-415-30187-4

- John F. White, Restorer of the World: The Roman Emperor Aurelian (Spellmount, 2004) ISBN 1-86227-250-6

- H. St. L. B. Moss, The Birth of the Middle Ages (Clarendon Press, 1935, reprint Oxford University Press, January 2000) ISBN 0-19-500260-1

- Ferdinand Lot, End of the Ancient World and the Beginnings of the Middle Ages (Harper Torchbooks Printing, New York, 1961. First English printing by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1931).

Further reading

- Crisis of The Third Century, Hugh Kramer.

- Map, University of Calgary.

- The Crisis of The Third Century, OSU.