Austrian Netherlands

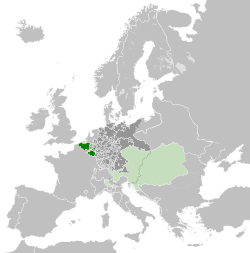

The Austrian Netherlands (Dutch: Oostenrijkse Nederlanden; French: Pays-Bas Autrichiens; German: Österreichische Niederlande; Latin: Belgium Austriacum) was the larger part of the Southern Netherlands between 1714 and 1797. The period began with the Austrian acquisition of the former Spanish Netherlands under the Treaty of Rastatt in 1714 and lasted until Revolutionary France annexed the territory during the aftermath of the Battle of Sprimont in 1794 and the Peace of Basel in 1795. Austria, however, did not relinquish its claim over the province until 1797 in the Treaty of Campo Formio.

Austrian Netherlands Österreichische Niederlande Pays-Bas Autrichiens Oostenrijkse Nederlanden Belgium Austriacum | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1714–1797 | |||||||||

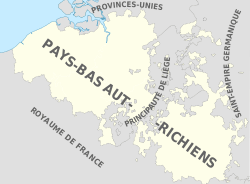

The Austrian Netherlands in 1789

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Status | Province of Austria State of the Holy Roman Empire | ||||||||

| Capital | Brussels | ||||||||

| Common languages | German, French, Dutch, Latin | ||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholic | ||||||||

| Government | Governorate | ||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||

• 1716–1724 | Francis Eugene (first) | ||||||||

• 1793–1794 | Charles Louis (last) | ||||||||

| Plenipotentiary | |||||||||

• 1714–1716 | Lothar Dominik (first) | ||||||||

• 1793–1794 | Franz Karl (last) | ||||||||

| Historical era | Early Modern | ||||||||

| 7 March 1714 | |||||||||

| 8 November 1785 | |||||||||

| 1789–1790 | |||||||||

| 18 September 1794 | |||||||||

| 1797 | |||||||||

| Currency | Kronenthaler | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

The Austrian Netherlands formed a non-contiguous territory that consisted of what is now western and central Belgium as well as greater Luxembourg, bisected by the Prince-Bishopric of Liège. The dominant languages were German (including Luxembourgish), Dutch (Flemish), and French, along with Picard and Walloon.

As a result of the Barrier Treaties of 1709-1715, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI (r. 1711–1740) showed little apparent interest in the day-to-day rule of the Austrian Netherlands; yet he insisted on keeping ultimate control of the territories concerned. This caused much frustration with Austria's own inhabitants, especially because the Dutch troops were paid with money that needed to be raised from the Austrian Netherlands themselves. The war of 1740-1748 showed that Austria already had little interest in maintaining the Austrian Netherlands: constant bickering among the Allied commanders meant the French kept the initiative during the campaigns, and the fortifications, manned with mostly Dutch troops, were captured with ease by the French army. Although the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle had stipulated that Dutch garrisons should again man the Barrier towns, Charles's daughter and successor Maria Theresa, advised by her counselor Kaunitz, refused to pay for those troops any longer, unless there were to be negotiations about new trade agreements. In the end, the Republic refused to pay for the rebuilding of the fortifications and or to send any troops, but with the Barrier towns in ruins and the Netherlands now open for a new invasion, she had little to offer. When Austria and France entered into an alliance in 1756, there was in effect no purpose in the Barrier treaty any more. In 1781 the Austrian archduke, Emperor Joseph II, unilaterally renounced the treaty.

History

Under the Treaty of Rastatt (1714), following the War of the Spanish Succession, the surviving portions of the Spanish Netherlands were ceded to Austria.

The Austrians were unconcerned with the upkeep of their province and the fortresses along the border (the Barrier Fortresses) were, by treaty, garrisoned with Dutch troops. The area had, in fact, been given to Austria largely at British and Dutch insistence, as these powers feared potential French domination of the region.

Charles VI attempted to use the Austrian Netherlands to compete with British and Dutch traders in an enterprise known as the Ostend Company.

Throughout the latter part of the eighteenth century, the principal foreign policy goal of the Habsburg rulers was to exchange the Austrian Netherlands for Bavaria, which would round out Habsburg possessions in southern Germany. In the Treaty of Versailles of 1757, Austria agreed to the creation of an independent state in the Southern Netherlands ruled by Philip, Duke of Parma and garrisoned by French troops in exchange for French help in recovering Silesia. However, the agreement was later revoked by the Treaty of Versailles of 1758 and Austrian rule continued.

In 1784 Joseph II did take up the long-standing grudge of Antwerp, whose once-flourishing trade was destroyed by the permanent closure of the Scheldt, and demanded that the Dutch Republic open the river to navigation. However, the Emperor's stance was far from militant, and he called off hostilities after the so-called Kettle War, known by that name because its only "casualty" was a kettle. Though Joseph did secure in the Treaty of Fontainebleau in 1785 that the Southern Netherlands would be compensated by the Dutch Republic for the continued closing the Scheldt, this achievement failed to gain him much popularity.

Brabant Revolution

In the 1780s, opposition emerged to the liberal reforms of Emperor Joseph II, which were perceived as an attack on the Catholic Church and the traditional institutions in the Austrian Netherlands. Resistance, focused in the autonomous and wealthy Estates of Brabant and Flanders, grew. In the aftermath of rioting and disruption, known as the Small Revolution, in 1787, many of opponents took refuge in the neighboring Dutch Republic where they formed a rebel army. Soon after the outbreak of the French and Liège revolutions, the émigré army crossed into the Austrian Netherlands and decisively defeated the Austrians at the Battle of Turnhout in October 1789. The rebels, supported by uprisings across the territory, soon took control over much of the territory and proclaimed independence. Despite the tacit support of Prussia, the independent United Belgian States, established in January 1790, received no foreign recognition and soon became divided along ideological lines. The Vonckists, led by Jan Frans Vonck, advocated progressive and liberal government, whereas the Statists, led by Hendrik Van der Noot, were staunchly conservative and supported by the Church. The Statists, who had a wider base of support, soon drove the Vonckists into exile through a terror.[1]

By mid-1790, Habsburg Austria ended its war with the Ottoman Empire and prepared to suppress the rebels. The new Holy Roman Emperor, Leopold II, was also a liberal and proposed an amnesty for the rebels. After defeating a Statist army at the Battle of Falmagne, the territory was soon overrun and the revolution was defeated by December. The Austrian reestablishment was short-lived, however, and the territory was soon overrun by the French during the French Revolutionary Wars.

Imperial Councillors of State

The Councillors of state acted as government, and formed the council by imperial consent:[2]

- The Baron von Reischach, Imperial Diplomat

- Cardinal von Migazzi

- Cardinal von Frankenberfg

- the Baron of Gottignies, Imperial Lord Chamberlain

- Philippe von Cobenzl, vice Chancellor of the Imperial Council of State.

- Henri d'Ognies, Prince of Grimberghen, Imperial Lord Chamberlain

- the Count of Neny; president of the Privy Council, member of the Imperial Council of State

- the Count of Woestenraedt, Imperial Lord Chamberlain.

- the Marquess of Chasteler, Lord Chamberlain

- the Count of Gomegnies, President of the Council of Hainaut

- the Viscount of Villers; Imperial Treasurer General

- the Prince of Gavre: Grand Marshall of the Imperial Court of the Archduchess.

French rule

In 1794, the armies of the French Revolution annexed the Austrian Netherlands from the Holy Roman Empire and integrated them into the French Republic.

Citations

Sources

- Heinrich Benedikt. Als Belgien österreichisch war. Herold, Vienna, 1965.