Crusader states

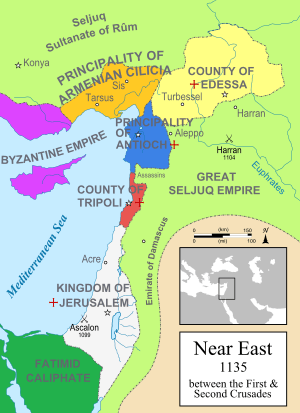

The Crusader states were four Roman Catholic polities created by the Crusaders as a result of the First Crusade. In 1098 the armed pilgrimage to Jerusalem passed through Syria. The crusader Baldwin of Boulogne took the place of the Greek Orthodox ruler of Edessa after a Coup d'état and Bohemond of Taranto remained as the ruling prince in the captured Antioch. In 1099, Jerusalem was taken after a siege. Territorial consolidation followed including the taking of Tripoli. At the states' largest extent territory covered the coastal areas of southern modern Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel and Palestine. These holdings were also known by the term "Outremer" from the French phrase outre-mer or "the land beyond the sea" and are often referred to as such by modern historians. Edessa fell to a Turkish warlord in 1144, but the other realms endured into the 13th century before falling to the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt. Antioch was captured in 1268, Tripoli in 1289. When Acre, the capital of the kingdom of Jerusalem fell in 1291 the last territories were quickly lost with the survivors fleeing to the Kingdom of Cyprus.

The study of the crusader states in their own right, as opposed to being a sub-topic of the Crusades, began in 19th century France as an analogy to the French colonial experience in the Levant. This was rejected by the 20th century historians where the consensus view was that the Franks, as the western European were known, lived as a minority society that was largely urban, isolated from the indigenous peoples, with separate legal and religious systems. The indigenous peoples were from Christian and Islamic traditions speaking Arabic, Greek and Syriac.

The crusader states were founded in the distant borderlands between the Byzantine and Seljuk Empires during a period when the regional polities were fragmented, the rulers were inexperienced, the Great Seljuk sultanate was both disinterested and declining. The confusion and division meant the Islamic world disregarded the world beyond; this made it vulnerable to, and surprised by, first contact with the Franks giving the Franks opportunities to consolidate.

Background

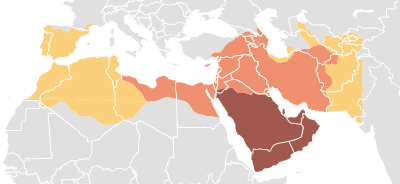

The period of Arab Islamic expansion had been over for centuries by the end of the 11th century.[1] The Christian and Muslim worlds still contested frontiers across the Mediterranean area. In what became known as the Reconquista, Christians campaigned in Spain. The Eastern Orthodox Christian Byzantine Empire stretched east to Iran and controlled Bulgaria and much of southern Italy in the west. The Empire was open to the possibility of western military aid for specific campaigns to support campaigns against the new enemies on all frontiers that stetched the its' resources. Normans led by Roger de Hauteville, later King Roger I of Sicily, seized Sicily from the Muslims.[2].[3][4]

The Middle East was permeated by Turkic migration. From the 9th century the Abbasid dynasty in Baghdad and other rulers used Turkic nomads as slave soldiers. These skilled horsemen and archers from the steppe were known as ghilman or mamluk. They were expected to remain loyal when converted to Islam. And emancipated Turks progressed from positions as guards to dynastic founders and eventually king makers. They founded dynasties in Egypt and Syria including the Mamluk Sultanate that destroyed the crusader states in the 13th century .[5][6] In the mid-11th century a minor clan of Oghuz Turks from Transoxania supplanted the Ghaznavids in Khurasan. These were named Seljuks after a warlord called Saljūq. They extended territorial gains into Iran and onto Baghdad where the caliph granted the title Sultan, power in arabic to the Seljuk Tughril This founded the Great Seljuk Empire and the Seljuq dynasty assimilated into Perso-Arabic culture.[7] The empire was decentralised, polyglot and multi-national. Junior members of the Seljuk family held the title Malik, the Arabic for king, and ruled provinces as appanages. The most powerful Mamluk in a province held the institutional position of atabeg, derived from ata meaning father and beg meaning commander. The atabegs were often guardians or regents with absolute power ruling on behalf of minors but their military leadership often continued when the malik reached majority. Through this atabegs often become emirs.[8]

The Turks’ arrival into Arab Islamic territory did not significantly impact on indigenous culture. The Byzantine Greeks who ruled what remained of the Eastern Roman Empire were on the offensive in the borderlands with the Seljuks. They captured Antioch after three centuries of Arab rule and invaded Syria. Turkish ghazi and Byzantine equivalents called Akritai, often also Turkish, indulged in ephemeral cross border raiding. Suljuk Sultan Alp Arslan was disinterested in Anatolia and there were treaties in place. In 1071 while securing his northern border he defeated Byzantine Emperor Romanos IV Diogenes at Manzikert.[9]} The Byzantine borders collapsed due to the capture of Romanos IV and the Byzantine factionalism that followed. This brought the ghazi and the nomadic tribesmen seeking pasture flooding into Anatolia.[10]

Alp Arslan's cousin Suleiman ibn Qutulmish carved out a new realm in Anatolia, seizing Cilicia and in 1084 peacefully entering Antioch. In 1092, he was defeated and killed in conflict with the Great Seljuk Empire.[10] This was part of a wider political disintegration. In the same year the vizier and effective ruler of the Seljuk Empire, Nizam al-Mulk, the Sultan Malik-Shah, the Mamluk Armenian vizier of Egypt Badr al-Jamali and the Fatimid khalif, Al-Mustansir Billah all died. Malik-Shah's brother Tutush, the atabegs of Aleppo and Edessa were killed in the succession conflict. Tutush's sons succeeded in Damascus and Aleppo but the atabegs were in control. Edessa was seized by an Armenian warlord. The war of succession in Egypt led to a split in the Ismāʿīlist branch of Shia Islam. A group founded by the Persian missionary Hassan-i Sabbah broke away and created the Nizari Ismaili state in Alamut, Iran. This was known as the New Preaching in Syria and Order of Assassins in western historiography. Targeted murder was utilised to compensate for their lack of military power and Nizam al-Mulk was their first victim.[11] The Islamic historian Hillenbrand has compared this fragmentation of Islamic politics at the end of the 11th century to the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989 using the phrase "familiar political entities gave way to disorientation and disunity".[12] When the crusading Franks reached Syria polities were fragmented, rulers inexperienced, the Great Seljuk sultanate and Fatamid Empire were disinterested and in decline.[13] The Islamic world disregarded the outside world making it vulnerable and surprised by the arrival of crusaders.[14]

The Christian kingdom of Lesser Armenia followed a similar pattern to the crusader states. It was located to the north-west of Syria and established on former Muslim territory retaken by the Byzantines in the 10th century. The Armenians immigrated from between Lake Van and the Caucasus. When the frontier collapsed after the battle at Manzikert they dominated Cilicia and territory east to the Euphrates. [15] Another ghazi state was founded at the time as the Sultanate of Rum, in north and central Anatolia by someone known by the Persian honourific Danishmend Gazi.[16]

The events the brought the Franks of the First Crusade to the region were unexpected by contemporary chroniclers, but historical analysis shows these followed precursors from earlier in the 11th century. Jerusalem was increasingly recognised in western Europe as worthy of pilgrimage. The numbers of pilgrims expanded after safer routes through Hungary developed from 1000. New devotional and penitential practise created fertile ground for crusading appeals.[17] The Franks' motivation may never be understood. One may have been a desire for penance through warfare. Historian Georges Duby suggested economic gain and improved social status for younger sons of nobles but this has been challenged. It does not account for the wider kinship groups in Germany and Southern France. Gesta Francorum mentions the economic attraction of gaining "great booty". Other possibilities include adventure, enjoyment of warfare and extended patronage systems that obliged the following of feudal lords.[18] The use of violence for dispute resolution in Western Europe was common supported by the development of a doctrine of holy war dating from the works of the 4th-century theologian Augustine. Augustine maintained that an aggressive war was sinful, but acknowledged a "just war" could be rationalised if it was proclaimed by a legitimate authority such as a king or bishop, was defensive or for the recovery of lands, and a without an excessive degree of violence.[19][20]

In 1054 a delegation to the Patriarch of Constantinople from Pope Leo IX ended in mutual excommunication and an East–West Schism other differences in custom, creed, and practice.[21] Pope Alexander II developed a system of recruitment via oaths for military resourcing that Gregory VII extended. [17] Conflict with Muslims on the southern peripheries of Christendom was sponsored by the Church, including the siege of Barbastro and fighting in Sicily[22] In 1071, Jerusalem was captured by the Turkish warlord Atsiz but Seljuk hold on the city was weak. Returning pilgrims reported difficulties and the oppression of Christians. Byzantine desire for military aid converged with increasing willingness of the western nobility to accept papal military direction.[23][24] Between the 1050s and the 1080s the Gregorian Reform movement made the papacy increasingly assertive, powerful and influential. The Eastern church viewed the pope as only one of the five patriarchs of the Church that included the Patriarchates of Alexandria, Antioch, Constantinople and Jerusalem. In 1074 Gregory VII had an ambition for a holy war supporting Byzantium against the Seljuks that would reinforce papal sovereignty but this did not progress.[25] Theologian Anselm of Lucca decisively argued that fighting for legitimate reasons could remit sin.[26]

History

Foundation

By the end of the 11th century the Byzantine army had a long history of using mercenary troops. Emperor Alexios I Komnenos appealed to Pope Urban II for military support in his conflict with the Turks. On 27 November 1095 at the Council of Clermont the Pope called for the First Crusade. In his preaching he offered absolution for the participants' sins.[27][28] The first response was a ground-swell of popular enthusiasm among poor Christians that led to what is now known as the People's Crusade. in October 1096, these crusaders were ambushed and annihilated by the Turks at Civetot. Feudal armies follwed under the command of western European nobles: Raymond IV, Count of Toulouse; Godfrey of Bouillon, Duke of Lower Lorraine; Robert, Duke of Normandy; Robert II, Count of Flanders; Stephen, Count of Blois; Hugh, Count of Vermandois and Bohemond, Prince of Taranto.[29]

The motivation of thoush who went on crusade may never be understood. Possible factors include the desire for penance, economic advancement, increased social status for younger, landless sons of the nobility, gaining loot, adventure, the enjoyment of warfare and the sociological explanation that some had no choice as they were embedded in extended patronage systems and obliged to follow their feudal lords.[18] Alexios welcomed cautiously the crusader leaders to Constantinople extracting promises from them to return to him recovered Byzantine territory. With the Byzantines Nicea was recaptured and in July 1097 the crusade was victorious over a united Seljuk and Danishmendid army in the Battle of Dorylaeum.[30][31]

The Byzantine commander Tatikios guided the crusade south through Anatolia after victory at Dorylaeum opened the path to Antioch. This large city controlled the road south to Jerusalem. The crusaders common purpose did not hide competition between leaders such as Bohemond's nephew, Tancred, and Godfrey's brother, Baldwin. They expelled Turkic garrisons from Cilician towns, before quarrelling over who would retain them. This led to armed conflict between the two sets of retainers. Antioch's governor Yağısıyan expelled all Christian men from the city and approached the Muslim rulers of Syria and Iraq for support. In October 1097 Baldwin left the crusade for the area on the west bank of the Euphrates, probably to join one side of an Armenian feud. The Armenians of two small northern Syrian towns, Turbessel and Rawandan, took advantage of his advance to expel the Turkish garrisons. The main army reached Antioch and with native Christian allies captured nearby fortifications. An English fleet secured the possession of the port of Saint Symeon. In February 1098 Tatikios left the crusade. The Franks defeated an army led by Ridwan of Aleppo.[32][33][34]

Thoros ruled Edessa, a Christian city that in terms of size and wealth matched Aleppo and Antioch. He hoped to hire Baldwin and his men as mercenaries and asked Baldwin for military support. Thoros's intention was to use them against the Turks and likely also against his Christian subjects in a city wracked with factional conflict. Matthew of Edessa reported that the Edessan population received Baldwin with enthusiasm. The local Armenian and Jacobite Christians regarded the Orthodox Thoros as a Byzantine representative and rebelled against him. In March 1098 and a month after Baldwin's arrival, a Christian mob killed Thoros. The mob accredited Baldwin with the Byzantine title used by Thoros, doux. Baldwin's position was personal rather than instituitional and the Armenian governance of the city remained in place. From an Edessan perspective this was replacing one strongman with vague Byzantine relationships with a similar one. Baldwin's territory consisted of small pockets surrounded by Turkish and Armenian warlords. The city of Edessa probably provided him a substantial income through its status as an important trading centre. The Euphrates river as well as the Armenian lords Abu'l-Garib and Kogh Vasil separated Edessa from Baldwin's other holdings in the nascent County of Edessa, Turbessel, Rawandan and Samosata.[35][36]

Stephen of Blois deserted the crusade at Antioch, and while returning to Europe told Emperor Alexios its defeat was imminent. In response to what he had been told, Alexios withdrew to the west rather than join the siege. Some crusaders, most notably Bohemond, claimed this and Tatikios departure were treacherous acts that freed them from their sworn oaths to the Byzantines. On 2 June, an Armenian commander helped Bohemond enter Antioch, taking the city but not the citadel. Hours later Kerbogha arrived, too late to save the city and the atabeg of Mosul besieged the crusaders. On 28 June the Franks defeated Kerbogha's army.[37] The Franks competed for the spoils, delaying departure for months. They captured Syrian towns such as Ma'arra and developed a reputation for savagery that prompted local emirs to negotiate rather than resist. The lack of progress to Jerusalem dismayed mobs of poor Franks. Raymond was forced to leave Bohemond in control of Antioch. He failed in an attack on Arqa before the Franks continued south towards Jerusalem.[38]

The crusaders marched along the Mediterranean coast to Jerusalem. The Fatimids had regained the city from the Seljuks in the second destructive siege the city had suffered in recent decades less than a year before.[39] On 15 July 1099 the city was taken after a short siege barely longer than a month. Thousands of Muslims and Jews were killed and the survivors were sold into slavery. Proposals to govern the city as an ecclesiastical state were rejected. Raymond refused the royal title claiming only Christ could wear a crown in Jerusalem. This may have been a ruse to dissuade his popular rival Godfrey from assuming the throne, but cleverly Godfrey adopted the title Advocatus Sancti Sepulchri, that is Advocate of the Holy Sepulchre, when he was proclaimed the first Frankish ruler of Jerusalem.[40][41] In Western Europe at that time an advocate, or advocatus, was a layman responsible for the protection and administration of Church estates.[42]

Consolidation (1099 to 1126)

In Egypt power rested with the chief minister or vizier, Al-Afdal Shahanshah. Godfrey defeated the counterattack he organised at Ascalon.[43] Godfrey's authority was challenged by Tancred and papal legate Daimbert of Pisa. Tancred seized Galilee and besieged Haifa. Daimbert was elected the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, extracting oaths of fealty from Godfrey and Bohemond. When Godfrey died, his followers enabled the succession of his brother Baldwin of Boulogne, preventing Daimbert or Tancred from seizing Jerusalem. Before leaving Edessa to assert his claim to Jerusalem, Baldwin ceded the county to his cousin, Baldwin of Bourcq. On Christmas Day 1100, Baldwin of Boulogne was crowned king of Jerusalem in Bethlehem. In March Bohemond was captured by the Danishmendids and Tancred went to Antioch to act as regent.[44]

Raymond laid the foundation of the fourth crusader state, the County of Tripoli between Antioch and Jerusalem before he died in 1105. He captured Tartus, Gibelet and besieged to Tripoli. The siege was continued by his cousin William II Jordan. In 1109, it was completed when Raymond's son Bertrand arrived to claim his domain. Baldwin I brokered a deal sharing the territory between Bertrand and William Jordan until William Jordan's sudden death enabled Bertrand to unite the county. The unification reduced Antioch's influence in favour of Jerusalem. William Jordan had been Tancred's vassal, but Bertrand acknowledged King Baldwin I's suzerainty.[45]

The Franks took advantage of fragmented Muslim politics to consolidate their position.[46] The Syrian Sunnis approached the Seljuk sultan, Barkiyaruq, for assistance in 1097 or 1098, but he was engaged in a power struggle with his brother Muhammad Tapar.[47][48] The Damascene jurist Ali ibn Tahir al-Sulami was most likely the first scholar to call for the jihād against the crusaders. In his Book of Holy War, he introduced the First Crusade in the wider context of Frankish expansion and reminded his co-religionists that disunity had enabled the Franks to seize territories in Spain, Sicily and the Levant.[49] The fall of Tripoli was the earliest shock inducing Sultan Muhammad to mobilize the armies of his empire's western provinces against the invaders.[50] The crusader states, or Outremer ("land beyond the sea"), took a special position among the countries on the fringes of Latin Christendom. Their rulers' role in protecting the Holy Land legitimised requests for military assistance from the European kings and popes. So, the First Crusade was followed by similar expeditions. The Crusade of 1101 was destroyed at Merzifon by an alliance of Turkish princes. Few crusaders survived the massacre and reached Syria and Palestine. Crusades could cause serious problems in the Outremer, their leadership did not always pay due regard to the opinions of Frankish rulers. The vast majority of the armed pilgrims quickly returned to their homeland, but their temporary presence could destroy lasting alliances between Frankish and Muslim rulers.[51][44]

The Fatimid Caliphate repeatedly invaded the new kingdom of Jerusalem in 1101, 1102 and 1105, on the last occasion in alliance with the Sunni Damascene atabeg Toghtekin. These invasions were repulsed by Baldwin I and he conquered the towns on the Palestinian coast with the support of Genoese, Venetian and Norwegian fleets. Only Tyre and Ascalon remained in Muslim hands. The Franks dominated the caravan route between Syria and Egypt through building castles in Oultrejordain.[52] Control of Antioch remained contested between the Byzantine Emperors and Bohemond I. In 1108, Bohemond launched a failed campaign against the Byzantine Empire from his Italian territory. The Byzantines and their Venetian allies forced Bohemond to accept the terms of the Treaty of Devol in which he acknowledged Byzantine suzerainty over the principality. Tancred who acted as regent in Antioch during Bohemond's absence rejected these terms.[53] Edessa was threatened by the Seljuk invasions to the east while both Bohemond and Tancred claimed suzerainty.[54] Unexpected coalitions were formed, such as in 1108 when the alliance between Tancred and Ridwan defeated Jawali and Baldwin in Turbessel. This resulted from Tancred's conflict with Baldwin of Bourcq, then Count of Edessa, and Ridwan of Aleppo's suspicion of the new atabeg of Mosul, Jawali Saqawa.[55] In 1112 Tancred died and his nephew, Roger of Salerno, assumed the regency of Antioch on behalf of Bohemond II of Antioch. Roger extracted tribute from Aleppo which was weakened by Ridwan's death and a resulting power vacuum.[56] THe devastation caused by the campaigns of Jawali's successor, Mawdud campaigns led to Turbessel replacing Edessa as the counts' preferred seat.[57]

Baldwin of Bourcq succeeded Baldwin I in Jerusalem in 1118. He ceded Edessa to Joscelin of Courtenay. Baldwin II remained involved in the defence of the Syrian crusader states, but the resulting repeated absences caused antagonism with the Jerusalemite nobility.[58][59] In 1119 the Artuqid Turk defeated and killed Roger at the Battle of Ager Sanguinis on the plain that became known as the "Field of Blood". Antioch survived, but only due to Baldwin II's prompt intervention. From then on, Antioch's frontiers were defended by Jerusalemite assistance.[60][61] In 1123, when Baldwin II was kidnapped in north Syria for sixteen months a group of barons attempted to depose him and offered the throne to the Flemish count, Charles the Good. Charles declined, and in 1125 the freed Baldwin II returned.[62] Bertrand's son, Pons stabilised Tripoli's position He enhanced relationships with Antioch by marrying Tancred's widow, Cecile of France.[63] In the 1120s the crusader states were effectively united under Baldwin II. Pons of Tripoli and Joscelin I of Edessa were his vassals and he was the regent in Antioch during the minority of Bohemond II. Baldwin II besieged Aleppo but instead in 1125 the city surrendered to Aqsunqur al-Bursuqi, the atabeg of Mosul. In 1126 Al-Bursuqi was assassinated, most likely by Nizari, weakening the union of Mosul and Aleppo.[64]

Opposition of Zengi, Nur ad-Din and Saladin (1127 to 1189)

In 1127, Seljuk sultan Mahmud appointed Imad al-Din Zengi Mosul's atabeg. The next year Zengi extended his rule to Aleppo. The Burid dynasty of Damascus were Zengi's principal Muslim rivals in Syria. Toghtekin tolerated a Nizari presence, but they were suppressed by the Damascenes after his death. Those that survived fled to the Nusayriyah Mountains and established a new base in the region.[65] Baldwin II had four daughters but no male heir. In 1126, Bohemond II of Antioch reached the age of majority and married Baldwin II's second daughter, Alice. Baldwin's heiress was his eldest daughter Melisende. Baldwin II married her to Count Fulk of Anjou. Jerusalem raised an imposing force for an offensive on Damascus including the leaders of the other crusader states; Bohemond II, Pons and Joscelin I. Fulk provided a significant Angevin contingent and the Templars had recruited forces in Europe. The campaign was abandoned after Atabeg Taj al-Muluk Buri destroyed the Franks foraging parties and bad weather made the roads impassable.[66] In 1130 Bohemond II was killed raiding in Cilicia. Baldwin was forced to Antioch, where he assumed the regency when Alice sought Zengi's help in taking control on behalf of her and Bohemond's daughter Constance.[67][68]

In 1131, Baldwin named Fulk, Melisende and their infant son, Baldwin as his co-heirs on his deathbed. Fulk ignored his father-in-law's will, attempting to rule independently. Between 1130 and 1135, Alice made repeated attempts to gain independent power in Antioch, including an alliance with Pons of Tripoli and the new Count of Edessa, Joscelin II. Fulk defeated Pons in a fierce battle and asserted control.[69] Melisende's kinsman, Hugh II of Jaffa was also unsuccessful resisting Fulk when he revolted. In 1136, Alice's struggle for power was ended when the anti-Byzantine Antiochene nobility asked Fulk to propose a husband for Constance and he selected Raymond of Poitiers. In response, John II Komnenos reasserted Byzantine claims of suzerainty in Cilicia and Antioch. He invaded Cilicia, expelled Antiochene and Armenian garrisons from Cilician towns, besieged Antioch and forced Raymond to become his vassal. Raymond promised that he would surrender Antioch in return for Aleppo and Shaizar when they were captured, but this was never achieved.[70][71][72] In 1137, Tripoli lost its eastern territories to Damascus, Pons was killed and Raymond II captured by Zengi.[73][74] The effective ruler of Damascus, Mu'in ad-Din Unur, sought Fulk's protection from Zengi and agreed payment of a tribute.[75]

In 1143 both the Emperor and Fulk died and the focus of the new Byzantine Emperor, Manuel I moved to other theatres: internal Byzantine conflict, in 1146 the passage through the Empire of the Second Crusade and war with the Normans in Sicily between 1146 and 1157.[76] Zengi and the Turkic Artuqids competed for control of northern Mesopotamia. Joscelin allied with the Artuqids, provoking Zengi's march to Edessa. On 24 December 1144 he captured the poorly defended town and then conquered the county west of the Euphrates.[77] In response, Pope Eugenius III declared another crusade in late 1145.[78]

In September 1146 Zengi was assassinated by his mamluk retainers or one of his Frankish slaves. His first son, Sayf al-Din Ghazi I, succeeded in Mosul, and his second, Nur ad-Din, in Aleppo.[79] Joscelin unsuccessfully attacked Edessa and Nur ad-Din destroyed the town.[80] From then on, a military campaign for Edessa was futile. Louis VIII of France did not recognise the Byzantine claim to Antioch and rejected Raymond's proposal to attack Aleppo and Shaizar. In June 1148 the French, Germans, Melisende and Baldwin III agreed an attack on Damascus at a conference in Acre. This was a failure and the crusade undertook no further military action.[81] The action brought temporary rapprochement between Damascus and Nur ad-Din. In 1149 there was a new Burid ruler, Mujir ad-Din Abaq, who revived the Damascene–Jerusalemite partnership.[82] Raymond of Antioch was killed fighting Nur ad-Din at Inab. The next year Joscelin was captured. Beatrice of Saone, his wife, sold the remains of the County of Edessa to the Byzantines. In 1150, Joscelin was captured, blinded and died in captivity. Next year, Baldwin III and Melisende's disagreements led to armed conflict and her abdication. This prevented him providing effective support to the Syrian crusader states. In 1153, he captured Ascalon and also sanctioned the marriage of Constance and Raynald of Châtillon during the siege.[83][84]

In 1154 Nur ad-Din captured Damascus easily from Mujir ad-Din Abaq's whose release of Frankish slaves and tribute payments to Jerusalem eroded his support. He rejected an anti-Frankish alliance proposed by Tala'i ibn Ruzzik, Egypt's vizier, and continued to pay the tribute to the Franks.[85] Reynald was acutely short of money. When the Emperor delayed promised payment for the suppression of raiding by the Armenian Thoros II he launched a piratical attack on Byzantine Cyprus. The arrival of Thierry, Count of Flanders provided the military strength for a new campaign. Thierry, Baldwin, Raynald and the young Count of Tripoli, Raymond III attacked Shaizar. After initial success Baldwin granted the city to Thierry. Raynald demanded that Thierry give him homage for it, but Thierry refused, and the siege was abandoned. Baldwin married Manuel's niece, Theodora. In 1158 Manuel invaded Cilicia and Antioch to reassert this authority. Reynald begged the Emperor for forgiveness and became his vassal.[86]

In 1162 Shawar, captured and executed Tala'i ibn Ruzzik's son and successor, Ruzzik ibn Tala'i. The following year Dirgham forced Shawar into exile. Amalric invaded Egypt when Dirgham refused to pay tribute but was forced to retreat when the Egyptians flooded the Nile Delta. Shawar fled to Damascus and sought Nur ad-Din's support. Nur ad-Din sent the Kurdish general Shirkuh with Shawar to Egypt. In 1164, he captured Cairo and Shawar was restored as vizier. Shawar approached Amalric for military assistance when he was unable to repay Nur ad-Din. For years both Shirkuh and Amalric repeatedly invaded Egypt but avoided direct confrontation.[87][88] In October 1168, Amalric assaulted Cairo. Shirkuh hurried to Egypt to answer an appeal for support from caliph Al-Adid. In January Amalric withdrew, Shawar was murdered, possibly by Saladin and a mamluk emir or alternatively through their political manoeuvring that forced Shirkuh to execute him. Al-Adid made Shirkuh vizier.[89] Within months, Saladin succeeded his dead uncle Shirkuh. in December, an invasion by Amalric with Byzantine naval support was abandoned at Damietta when the attackers ran out of provisions.[90] Nur al-Din demanded that Saladin brought Egypt into Abbasid Caliphate by removing of the Shi’ite Fatimids. Saladin was helped in this by the death through illness of al-Adid. A week later, the Fatimid regime was ended and the Friday khutbah was proclaimed in the name of the Abbasid caliph Al-Mustadi without dissent.[89] The Ayyubid family determined to resist any attempts by Nur ad-Din to assert authority in Egypt, but to adopt a conciliatory public tone. In March 1171, Amalric undertook a surprising visit to Manuel in Constantinople. His aim was that in the absence of support from the west he would get Byzantine military support for an attack on Egypt. In return, John Kinnamos reports he agreed to "his subjection" to the Romans.[91]

In 1174 Nur ad-Din and Amalric both died. Nur ad-Din left an eleven-year-old son, As-Salih Ismail al-Malik. As-Salih moved from Damascus to Aleppo and the city surrendered to Saladin without resistance. Saladin's determination to reunite Nur ad-Din's empire led to twelve years of warfare with the Zengid rulers of Syria and Iraq. Amalric's 13-year-old son, Baldwin IV was a leper and expected to die young. He became king and Miles of Plancy took control of the government. He was Seneschal of Jerusalem, lord of Transjordan through marriage to Stephanie of Milly and as a member of the Montlhéry family related to Baldwin II and his descendants. Raymond III of Tripoli appealed to the high court on the grounds he was Baldwin's closest relative and was granted the role of bailli and the rule of the kingdom. He married the richest heiress of the kingdom, Eschiva of Bures giving him Galilee and making him the most powerful baron.[92]

In July 1176 Baldwin turned 15, the age of majority, and Raymond's role ended. Baldwin revisited plans for a Byzantine alliance and a joint invasion of Egypt.[93] In November, Sibylla was married to William of Montferrat. Sibylla was Baldwin's heir. William was the cousin of both Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa and Louis VII of France. In the Summer of 1177, William died, leaving Sibylla pregnant, Jerusalem vulnerable and the succession unresolved. In September 1177, Fulk's grandson, Philip I, Count of Flanders arrived in the Holy Land with a Flemish army and he was offered the regency.[94] In September, an embassy from the Byzantine Emperor, led by the Sicilian Alexander of Gravina arrived in the kingdom with a fleet of seventy galleys plus support ships. Phillip wanted to be free to return to Flanders, suspected he would be blamed if an attack on Egypt failed and if it succeeded Baldwin or the Byzantines would rule Egypt. He rejected an attack on Egypt and instead he, Tripoli and Antioch unsuccessfully attacked Hama and Harim. In November, with most of the Frankish forces in North, Saladin invaded from the South, but was defeated by Baldwin at Montgisard. Baldwin negotiated for a marriage between Hugh III, Duke of Burgundy and Sibylla but for years the succession crisis in France prevented him sailing. Early in 1180 Baldwin married Sybilla to Guy of Lusignan. William of Tyre explains this as Baldwin's method of foiling what he believed was a plot by Raymond III of Tripoli and Bohemond III of Antioch to depose him and elevate Sibylla to the throne under their control. The two men had entered the kingdom, supposedly to celebrate Easter at Jerusalem. The marriage divided the nobility between a "court party" of the king’s maternal kin and a group that included Baldwin’s relatives descended from Queen Melisende’s sisters, Raymond of Tripoli, Bohemond of Antioch and the Ibelins. Saladin and Jerusalem made a truce that lasted from 1180 until 1182. [95]

In the summer of 1182, the conflict reignited. Saladin demonstrated the strategic advantage he held by holding both Cairo and Damascus. While he faced Baldwin at Kerak, Turkish troops from the North attacked east of Tiberias. He also reestablished his naval forces. Early in 1183 the Franks levied an extraordinary tax for defence funding. In June Saladin captured Aleppo. Three years later he would complete the suppression of the Zengids by gaining control of Mosul. In September Guy became bailli taking command of the defence of Jerusalem.[96] In September, Saladin invaded Galilee. In response the Franks raised what William of Tyre described as their largest army in living memory. After nine days of fierce skirmishing but no pitched battle Saladin withdrew towards Damascus. Baldwin dismissed Guy from his position as bailli for failing to fully engage the enemy, although some historians such as R.C. Small believe it was this was the result of obstruction by Guy’s baronial enemies. Baldwin went further in November crowning Guy's 5-year-old stepson, Baldwin V, as co-ruler while attempting to annul the marriage of Guy and Sibylla. Before Guy could be completely ostracised Saladin attacked Kerak, possibly in revenge for Reynald of Châtillon’s attack on a caravan in 1182 and naval raiding in the Red Sea during 1183. After Baldwin forced Saladin’s retreat, Guy and Sibylla fled to Ascalon. In response to Guy’s resistance, Baldwin handed Raymond governmental control. An embassy to Europe, meeting the Pope, Philip II of France and Henry II of England was met with offers of money but not of military support.[97]

Early in 1185 Baldwin IV knew he didn’t have long to live, so he called a council of the Frankish barons. Raymond became bailli for ten years. Baldwin V was put under the protection of Joscelin, which also protected Raymond, who was the nearest male relative, from suspicion should the boy die prematurely. As there was no consensus on what should happen in that event it would be for the pope, the Holy Roman Emperor, the kings of France and England to decide between the succession claims of Sibylla and her half-sister Isabella.[98]

In 1186 Baldwin V died. Joscelin seized Acre and Beirut while Sibylla and her supporters gained control in Jerusalem.[99] Raymond and the barons response was to find an alternative candidate. They choose Isabella’s husband Humphrey IV of Toron but instead he submitted to Sibylla to avoid a civil war. The barons were left with no alternative but to accept the new rulers, only Raymond and Baldwin of Ibelin resisted.[99] Reynald seized another caravan, which in Saladin’s view violated a four year truce and prompted him to assemble his forces for another invasion. Raymond made a treaty with Saladin and allowed Saladin’s troops to pass through his territory to raid around Acre. However, his shock at the Frankish defeat in the resulting Battle of Cresson brought him to reconciliation with Guy. Guy and the barons now gathered a united force numbering 40,000 according to Ernoul. The Franks were divided on tactics. Raymond urged defensive caution while Reynald and the master of the Templars, Gerard de Ridefort urged Guy to attack. They considered that Raymond was a traitor.[100] Guy was persuaded to march to lift Saladin’s siege of Tiberias. The march across Galilee was arduous and Saladin used his forces separate the Franks from water supplies. On 4 July 1187 Raymond attacked, aiming to gain the springs at Hattin. The Franks trampled some of their own men and the Muslims retreated. The survivors included Raymond, his stepsons, Raymond of Antioch, Reynald of Sidon, Balian and Joscelin. They left the battle making their way 10 miles north to Safed and eventually Tyre. The remains of the Frankish army retreated up the Horns of Hattin to regroup on higher ground but were overwhelmed and the battle was lost. All the major Frankish leaders were taken prisoner including Guy, Gerard, Reynald of Châtillon, William of Montferrat, Aimery of Lusignan, Humphrey and Hugh of Gibelet.[101]

Imad ad-Din al-Isfahani reports Saladin beheaded Reynald himself. Terricus who was the most senior surviving Templar, wrote that 230 Templars were beheaded. Hattin was a massive defeat for the Franks. Guy had committed all the available Frankish resources. Letters to Europe describe it as a military defeat that had cost 25,000 lives in a single day. Eschiva surrendered Tiberias assuming that Raymond and her sons were lost. Joscelin submitted Acre and the citizens were given forty days to leave. According to Terricus by August the kingdom only retained Jerusalem, Ascalon, Tyre and Beirut. He did not realise that the great inland castles held out. Beirut fell quickly and the coastal towns followed without great loss of life, but numerous Christians were enslaved. On 4 September Ascalon surrendered in return for safe passage to Jerusalem and freedom for ten people. These included Guy, his brother Aimery, the marshal, and Gerard of Ridefort. Although Guy was not released until the following July. On 2 October 1187, Balian handed the keys. of Jerusalem to Saladin and those inhabitants who could afford ransom were released. Tyre resisted; its defences commanded by Conrad who was William of Montferrat's brother. He had arrived in the Holy Land only days after Hattin. Late in the year Raymond died leaving Tripoli to Raymond; his godson, Bohemond III's eldest son and heir. Instead Bohemond empowered his younger son, Bohemond IV. In mid-May 1188 Saladin turned his attention to Tripoli and Antioch. Tripoli was saved by the arrival a William II of Sicily’s Sicilian fleet consisting of maybe sixty galleys and 200 knights. Ernoul wrote that William sent another 300 knights the following August. In July at the siege of Tortosa , Saladin released Guy of Lusignan and William of Montferrat on condition that they did not bear arms against him and that Guy went overseas. In October the following year, after fierce fighting outside Acre, Saladin accused Guy of breaking his oath. Bohemond asked Saladin for a seven-month truce, offering the release of Muslim prisoners. Also, if help did not arrive the city was to be handed over. Ali ibn al-Athir wrote after the Frankish castles were starved into submission that “the Muslims acquired everything from as far as [Ayla to the furthest districts of Beirut with only the interruption of Tyre and also all the dependencies of Antioch, apart from al-Qusayr”.[102]

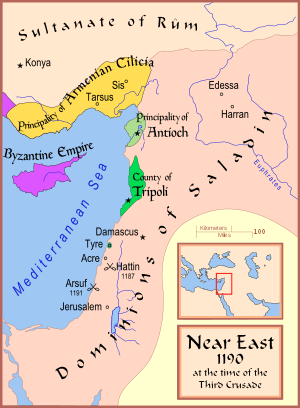

Recovery (1190 to 1229)

The anonymous Historia de expeditione Friderici imperatoris records that in June 1190 Emperor Frederick Barbarossa drowned crossing the Saleph River, although it may have been a heart attack. Frederick was leading a crusading force overland of between twelve and fifteen thousand. On his death the force suffered disease and fragmented.[103] According to Ernoul in August Guy, his brothers Geoffrey and Aimery, Gerard of Ridefort and Andrew of Brienne mustered a force of 600 knights and where refused entry to Tyre by Conrad. Convinced that crusaders from the West would soon arrive they decided to make a token move on Acre with an inadequate force. A steady steam of Crusaders arrived in support including in October 1190 Frederick's son Frederick, in April 1191 Philip II of France and two months later Richard I of England. Sibylla died In the autumn of 1190 allowing Conrad to argue that Guy had no legitimacy. According to Ambroise and Itinerarium Peregrinarum et Gesta Regis Ricardi, Conrad bribed the princes in the army to allow him to marry Isabella, Sibylla’s half-sister despite her marriage to Humphrey of Toron and the widespread belief that he himself already had two living wives. Those hostile sources describe Isabella's mother Maria Comnena as "steeped in Greek filth from the cradle" and similarly describing her husband Balian of Ibelin's morals. On the 12 July and after an attritional siege the Muslim garrison surrendered Acre. At this point Philip and most of the French army returned to Europe.[104] Now led by Richard the crusade defeated Saladin at Arsuf and captured Jaffa, Ascalon and Darum. Internal dissension was disintegrating the crusade forcing Richard to abandon Guy and accept the general will that Conrad become king. Guy was compensated with the island of Cyprus that Richard had captured in transit. On 28 April 1192 this arrangement failed when Conrad was murdered in Tyre by two Assassins. One week later Henry, Count of Champagne was king through marriage to Isabella.[104]

Richard could not destroy Saladin’s army or risk an attack on Jerusalem. He had to return to attend to manage his affairs in the West and was ill. On 2 September a three-year truce was agreed. The Franks retained lands between Tyre and Jaffa, but dismantled Ascalon, Antioch and Tripoli were included and pilgrimages to Jerusalem allowed by Saladin. Frankish confidence in the truce was not high. In April 1193, Geoffroy de Donjon, the Grand Master of the Hospitaller wrote in a letter, "We know for certain that since the loss of the land the inheritance of Christ cannot easily be regained. The land held by the Christians during the truces remains virtually uninhabited." Five months after Richard's departure Saladin unexpectedly died.[105]

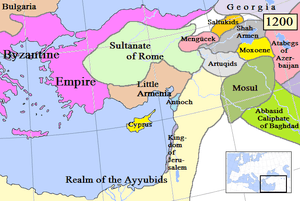

Historian Claude Cahen described the early 13th century history of northern Syria as "a lack of conflicts with the Muslims, [but] constant conflicts with the Armenians". The Armenians of Cilicia became increasingly independent after the 1176 Byzantine defeat by the Seljuks at Myriokephalon ended Greek control in Cilicia and northern Syria. In 1185, during an Armenian civil war Bohemond III of Antioch forced his guest, Ruben III, Prince of Armenia, into becoming his vassal. When Roupen died, his brother Leo supplanted his daughter and heiress, Alice. In 1191, Leo occupied the Templar castle of Bagras that had been abandoned by Saladin after three years of possession. In 1194, Bohemond III accepted Leo's invitation to discuss terms for its return, but Leo imprisoned him in retaliation for the earlier imprisonment of Ruben. Leo demanded Antioch for Bohemond III's release. The Greek Orthodox population and Italian community rejected the idea of an Armenian ruler. Instead they formed a commune and installed Bohemond's eldest son, Raymond. Bohemond III was released in return for abandoning his claim over Cilicia, forfeiting Bagras and marrying Raymond to Alice. Any male heir of this marriage would be considered the next ruler of both Antioch and Armenia. Raymond died first. Bohemond III's second son, Bohemond IV, was recognised as heir by the commune while Alice and Raymond's posthumous son, Raymond-Roupen, were exiled to Cilicia.[106]

Bohemond III died in 1201. The commune of Antioch renewed its allegiance to Bohemond IV, although a number of the nobility felt compelled to support Raymond-Roupen and joined him in Cilicia. Bohemond requested aid from Saladin's son, Az-Zahir Ghazi of Aleppo and Suleiman, the Sultan of Rûm. They invaded Cilicia. This forced Leo to abandon his invasion in support of his great nephew. Bohemond IV was often absent asserting his control in Tripoli. In 1203 the Templars prevented Leo taking advantage, in 1205/1206 it was Az-Zahir Ghazi. In 1207/1208 Bohemond suppressed an Antiochene revolt by Peter of Angoulême, the Latin patriarch of Antioch, and the exiled nobles. Leo and Raymond-Roupen exhausted Antioch with frequent destructive raids through the surrounding country and in 1216 occupied the city during another of Bohemond IV's absences. Leo left to address open warfare in Cilicia with the Anatolian Seljuks. The relationship between Leo and Raymond-Roupen soured and Bohemond IV's supporters took advantage, restoring him in 2019. Raymond-Roupen fled to Armenia, firstly seeking Leo's support and when Leo died in May attempting to gain the throne.Constantine of Baberon who was regent for Leo's younger daughter, Isabellal, acted quickly. He captured Raymond-Roupen, who then died in prison. Isabella was married to Bohemond IV's son, Philip. In late 1224, Phillip was abducted and poisoned by Armenian nobles. Bohemond attempts at revenge were foiled by an alliance between the Armenians and Bohemond IV's former Ayyubid allies in Aleppo.[107]

In September 1197 Henry of Champagne died falling out of a palace window in Acre when the railings gave way.[108] The same month Emperor Henry also died unexpectedly in Sicily, but news of his death did not reach the Outremer for months. In the meantime the Germans and the Franks captured Beirut and Sidon and Bohemond III seized two defenceless towns, Lattakia and Jubail.[109] In January 1198, the widowed Queen Isabella married Aimery of Cyprus.

Saladin's brother Al-Adil I ruled tha majority of the Ayyubid realms while his third son Az-Zahir Ghazi retained Aleppo. Al-Adil agreed almost constant truces with the Franks: 1198 to 1204, 1204 to 1210 and 1211 to 1217). This allowed him to concentrate on the threats presented by the Zengids of Mesopatamia, the Seljuks of Anatolia, the Christian states of Armenia and Georgia.[110]

In 1205 Aimery and Isabella died leaving Isabella's daughter by Conrad, Maria of Montferrat, to succeed. Isabella's half-brother, John of Ibelin assumed the regency.[111] In 1207, Al-Adil invaded the County of Tripoli and forced the Franks to release their Muslim prisoners and to pay a yearly tribute to him.[112] The Jerusalemite nobles sent a delegation to France, requesting King Philip to appoint Queen Mary's husband. He chose a baron from Champagne, John of Brienne. In 1210 John married the Queen and they were crowned in Tyre. A Jerusalemite fleet pillaged Damietta, but John and Al-Adil signed a new truce for five years. After Mary died in childbirth in 1212, John ruled the kingdom in the name of their infant daughter, Isabella II.[113][114]

In 1213 Pope Innocent proclaimed the Fifth Crusade—the first crusade to be preached not only in Europe, but also in the Outremer. John of Brienne and Bohemond IV were quick to take the cross.[115] Emperor Henry VI's son, Frederick II, also pledged to join the crusade, but difficulties in his German and Sicilian realms prevented him from departing for the Outremer.[116]

Andrew II of Hungary and Leopold VI of Austria were the first leaders of the new crusade to reach the Holy Land in late 1217, but Andrew quickly abandoned the campaign. The crusaders invaded Egypt and laid siege to Damietta. They acknowledged John of Brienne as their supreme commander, but Pope Innocent's legate, Cardinal Pelagius, challenged his authority as soon as he landed at Damietta, accompanied by fresh troops.[117][118] In November, Damietta fell to the crusaders. Al-Adil's son and successor, Al-Kamil offered to return almost all lands that Saladin had conquered from the Franks in return for the crusaders' withdrawal from Egypt. After Pelagius vetoed the agreement, John left Egypt on the pretext of asserting his wife's claim to Cilicia, but Stephanie and their son died. He returned to Egypt and the crusaders moved south to Mansoura, a newly built Egyptian fortress on the Nile, but the flood forced them to start negotiations with Al-Kamil. In August 1221, Al-Kamil signed an eight-year truce in return for Damietta and the withdraval of all crusader troops from Egypt.[119][120]

Although Emperor Frederick II renewed his crusading oath in 1218 and 1221, the crusade was delayed on both occasion. In 1225 Frederick married John of Brienne's daughter, Queen Isabella and had himself crowned King of Jerusalem despite previously agreeing that John would hold the title for life.[121] Fearing a new invasion of Egypt, Al-Kamil offered an alliance to Frederick against his brother, Al-Mu'azzam Isa, who held Palestine, promising the restoration of significant territory to the Franks. In September 1227, Frederick set sail for the Holy Land, but a sudden illness forced him to return to Italy soon. The new delay provided Pope Gregory IX with a pretext to excommunicate him and demand the imposition of papal suzerainty over Sicily.[116][122]

Queen Isabella died after giving birth to a son, Conrad. From then on, Frederick ruled the kingdom as regent for his infant son. Ignoring the Pope's ban, Frederick resumed the crusade, although he could no more rely on Al-Kamil. Al-Mu'azzam had died and Al-Kamil was unwilling to renounce Palestinian land by then in his possession. Frederick's attempts to assert his sovereign rights in Cyprus brought him into conflict with John of Ibelin who had administered the island on behalf of the underage King Henry I. Frederick accused Ibelin of embezzlement and wanted to confiscate his estates both in Cyprus and the mainland, but the Jerusalemite barons resisted, claiming that Ibelin's mainland domain could not be seized as a punishment for his acts in the island.[116][123] Frederick landed at Acre in June 1228. Although his army was inadequate to wage war against Al-Kamil, his knowledge of Arabic and his familiarity with Muslim customs facilitated his negotiations with the Sultan's envoys. In his absence, John of Brienne launched a "crusade"—a military campaign sanctioned by the Pope—against his Sicilian realm, forcing Frederick to conclude a treaty with Al-Kamil. Al-Kamil agreed to cede Bethlehem, Nazareth and Jerusalem, save the Temple Mount, and parts of Galilee to the Franks, stipulating that Jerusalem was to remain open to Muslim pilgrims. The treaty also included a truce for ten years, ten months and ten days (the maximum period allowed by Islamic custom). It was signed in February 1229, although both militant Muslims and Christians regarded it as a treachery. Frederick visited the Church of the Holy Sepulchre to wear his royal crown in public, but the clergy did not attend the ceremony celebrating an excommunicated monarch. Frederick disembarked at Acre for Italy in May 1229.[124][125][126]

Demography and Society

Modern research using historical geography techniques indicate that Muslims and indigenous Christian populations were less integrated than historians previously thought. Palestinian Christians lived around Jerusalem and in an arc stretching from Jericho and the Jordan to Hebron in the south.[127] Comparisons of archaeological evidence of Byzantine churches built prior the Muslim conquest and 16th century Ottoman census records demonstrate that while some Greek Orthodox communities had disappeared prior the crusades, most continued during and for centuries after the crusader states. Maronites were concentrated in Tripoli; Jacobites in Antioch and Edessa. Armenians were concentrated in the north but communities existed in all major towns. Palestine's central areas had a Muslim majority population. The Muslims were mainly Sunnis, but Shi'ite communities existed in Galilee. The nonconformist Muslim Druzes were recorded living in the mountains of Tripoli. The Jewish population resided in coastal towns and some Galilean villages.[128][129] Little research has been done on Islamic conversion but the limited available evidence led Ellenblum to believe that around Nablus and Jerusalem Christians remained a majority.[130]

Peasants living off the land formed the vast majority of the indigenous population, particularly after the massacres and sieges of the early 11th century led to widespread death and emigration among the native city dwellers. Charters from the beginning of the 12th century show evidence of the donation of local villeins to nobles and religious instituitions. This may have been a method of denoting the revenues from these villeins or land where the boundaries were unclear. These are described as villanus, surianus for Christians or sarracenus for Muslims. The term servus was reserved for the numerous urban, domestic slaves the Franks held in Jerusalem. The use of villanus is thought to possibly reflect the higher status that villagers or serfs held in the near East or that the indigenous men referred to were considered to have servile land tenures rather than that they lacked personal freedom. The difference between the Western serf and Near Eastern villein was that the latter could marry outside their lords' domain, were not obliged to perform unpaid labour, could hold land and inherit property. However, because the Franks needed to maintain productivity the villagers were tied to the land. Charters evidence landholders agreeing to return any villeins from other landholders they found on their property. Peasants were required to pay the lord one quarter to a half of crop yields, the Muslim pilgrim Ibn Jubayr reported there was also a poll tax of one dinar and five qirat per head and a tax on produce from trees. 13th century charters indicate this increased after the loss of the first kingdom to compensate the Franks for the resulting loss of income. These are the reasons that the use of the term indentured peasant is considered by historian Christopher MacEvitt to be a more accurate description for the villagers in the Latin East rather than serf.[131]

The Frankish population of the Kingdom of Jerusalem was concentrated in three major cities. By the 13th century the population of Acre probably exceeded 60,000, then came Tyre, with the capital being the smallest of the three with a population somewhere between 20,000 and 30,000.[132] At its zenith, the Latin population of the region reached c. 250,000 with the Kingdom of Jerusalem's population numbering c. 120,000 and the combined total in Tripoli, Antioch and Edessa being broadly comparable.[133] The presence of Frankish peasants is evident in 235 villages, out of a total of some 1,200 rural settlements.[134] Some were planned villages, established to encourage settlers from the West and some were shared with native Christians. The native population lived in casalia, or rural settlements, each including the dwellings of about 3-50 families.[135] In context, Josiah Russell estimates the population of what he calls "Islamic territory" as roughly 12.5 million in 1000—Anatolia 8 million, Syria 2 million, Egypt 1.5 million and North Africa 1 million — with the European areas that provided crusaders having a population of 23.7 million. He estimates that by 1200 that these figures had risen to 13.7 million in Islamic territory—Anatolia 7 million, Syria 2.7 million, Egypt 2.5 million and North Africa 1.5 million— while the crusaders' home countries population was 35.6 million. Russell acknowledges that much of Anatolia was Christian or under the Byzantines and that some purportedly Islamic areas such as Mosul and Baghdad had significant Christian populations.[136]

The Franks ruled as an elite and outnumbered class. As such, linguistic differences remained a key differentiator between the Franks lords and the local population. The Franks typically spoke Old French and wrote in Latin. While some learnt Arabic, Greek, Armenian, Syriac and Hebrew this was unusual.[137] Society was politically and legally stratified, with self-governing, ethnically-based communities. Though relations between communities were controlled by the Franks.[138] Research into the society of the crusader states focussed on the role of the ruʾasāʾ, Arabic for leader, chief or mayor. Riley-Smith divided these into the urban, those that he considered freemen, and the rural who were tied to the land. Not only did these men administer the Frankish estates and govern the native communities but evidence indicates they were often respected local landowners in their own right. If the communities were segregated as indicated by the written evidence and identified by Riley-Smith and Prawer inter-communal conflict was avoided because interaction between the landed and the peasants was limited. Alternatively, McEvitt identifies possible tension between competing groups. According to the 13th century jurists, in the towns the Rais presided over the Cour des Syriens and there is other evidence that on occasion they led local troops.[139] Civil disputes and minor criminality were administered by these courts of the indigenous communities, but more serious offences and cases involving Franks were dealt with by the Frankish cour des bourgeois or courts of the burgesses, the name given to the non-noble Franks.[140] The lack of material evidence makes it difficult to identify the level of assimilation. The archaeology is culturally exclusive and written evidence indicates deep religious divisions, although some historians assume that the states' heterogeneity eroded formal apartheid.[141] The key differentiator in status and economic position was between urban and rural dwellers. Indigenous Christians could gain higher status and acquire wealth through commerce and industry in towns, but few Muslims lived in urban areas except those in servitude.[142]

Frankish courts reflected the region's diversity. Queen Melisende was part Armenian and married Fulk from Anjou. Their son Amalric, first married a Frank from the Levant, then a Byzantine Greek. William of Tyre was appalled at the use of Jewish, Syrian and Muslim physicians, who were popular among the nobility. Greek and Arabic speaking Christians made Antioch a centre of cultural interchange. The indigenous peoples showed the Frankish nobility traditional deference. Some Franks adopted the their dress, food, housing and military techniques. This does not mean that Frankish society was a cultural melting pot. Inter-communal relations were shallow, separate identities were maintained and other communities were considered alien.[143]

Economy

In addition to being economic centres themselves, the crusader states provided an obstacle to Muslim trade by sea with the west and to the land routes from Mesopotamia and Syria to the great urban economies of the Nile. Despite hostility, commerce continued, coastal cities remained maritime outlets for the Islamic hinterland and eastern wares were exported to Europe in unprecedented volumes. The Byzantine-Muslim mercantile growth in the 12th and 13th centuries may have occurred anyway, as the Western European economy was booming due to population growth; this increased wealth and created a growing social class demanding city centred products and eastern imports, but it is likely that the Crusades hastened the developments. European fleets were expanded, better ships built, navigation improved and fare paying pilgrims subsidised many voyages. Agricultural production, largely the domain of the indigenous population, flourished before the fall of the First Kingdom in 1187, but was negligible afterwards. Franks, Muslims, Jews and indigenous Christians traded crafts in the souks, teeming oriental bazaars, of the cities.[144] Olives, grapes, wheat and barley were the most important agricultural products before Saladin's conquests. Glass making and soap production were major industries in the towns.[145] The Italian, Provençal and Catalan merchants monopolised shipping, imports, exports, transportation and banking. The Frankish noble and ecclesiastical institutional income was based on income from estates, market tolls and taxation.[146] Seigniorial monopolies, or bans, existed, compelling the peasantry to use the landowners' mills, ovens and other facilities. The presence of hand-mills in most households implies that the serfs sometimes circumvented their lords' monopolies.[147] The main centres of production were Antioch, Tripoli, Tyre and, less importantly, Beirut. Textiles, glass, dyestuffs, olives, wine, sesame oil and sugar were exported; silk was particularly prized.[148] The Frankish population, estimated at roughly a quarter of a million people, provided an import market for clothing and finished goods.[149]

The Franks adopted the more monetised indigenous economic system, using a hybrid coinage: predominantly northern Italian and southern French silver European coins; Frankish variant copper coins minted in Arabic and Byzantine styles; and silver and gold dirhams and dinars. After 1124, Egyptian dinars were copied, creating Jerusalem's gold bezant. Following the collapse of the first kingdom of Jerusalem in 1187, trade, rather than agriculture, increasingly dominated the economy and western coins began dominating the coinage in circulation. Although lords in Tyre, Sidon and Beirut minted silver pennies and copper coins there is little evidence of systematic attempts to create a unified currency.[150]

Monarchy

During the period of near constant warfare in the early decades of the 12th century, the king of Jerusalem's foremost role was leader of the feudal host. They very rarely awarded land or lordships, and those awarded that became vacant—a frequent event due to the high mortality rate in the conflict—reverted to the crown. Instead their followers' loyalty was rewarded with city incomes. As a result, the royal domain of the first five rulers —including much of Judea, Samaria, the coast from Jaffa to Ascalon, the ports of Acre and Tyre, and other scattered castles and territories—was larger that the combined holdings of the nobility. This meant that the rulers of Jerusalem had greater internal power than comparative western monarchs, although they did not have the necessary administrative systems and personnel to govern such a large realm.[151]

The situation evolved in the second quarter of the century with the establishment of baronial dynasties. Magnates—such as Raynald of Châtillon, Lord of Oultrejordain, and Raymond III, Count of Tripoli, Prince of Galilee—often acted as autonomous rulers. Royal powers were abrogated and effectively governance was undertaken within the feudatories. What central control remained was exercised at the Haute Cour—High Court, in English. Only the 13th century jurists of Jerusalem used this term, curia regis was more common in Europe. These were meetings between the king and his tenants in chief. Over time the duty of the vassal to give counsel developed into a privilege and ultimately the legitimacy of the monarch depended on the agreement of the court.[152] In practice, the High Court consisted of the great barons and the king's direct vassals. In law a quorum was the king and three tenants in chief. The 1162 the assise sur la ligece theoretically expanded the court's membership to all 600 or more fief-holders, making them all peers. All those who paid homage directly to the king were now members of the Haute Cour of Jerusalem. They were joined by the heads of the military orders by the end of the 12th century, and the Italian communes in the 13th century.[153] The leaders of the Third Crusade ignored the monarchy of Jerusalem; the kings of England and France agreed on the division of future conquests as if there was no need to take into account the nobility of the crusader states. Joshua Prawer considered that the weakness of the crown of Jerusalem was demonstrated by the rapid offering of the throne to Conrad of Montferrat in 1190 and then Henry II, Count of Champagne in 1192.[154] This was given legal effect by Baldwin IV's will stipulating if Baldwin V died a minor the Pope, the kings of England and France, and the Holt Roman Emperor should select the successor.[155]

Before the defeat at Hattin in 1187 the laws developed by the court were documented as assises in Letters of the Holy Sepulchre.[156] After Hattin the Franks lost their cities, lands and churches. Many barons fled to Cyprus and intermarried with leading new emigres from the Lusignan, Montbéliard, Brienne and Montfort families. This created a class apart from the remnents of the old nobility with limited understanding of the Latin East including the king-consorts Guy, Conrad, Henry, Aimery, John and the absent Hohenstaufen that followed.[157] The entire body of written law was lost in the subsequent fall of Jerusalem. From this point the legal system was largely based on custom and the memory of the lost legislation. The renowned jurist Philip of Novara lamented "We know [the laws] rather poorly, for they are known by hearsay and usage...and we think an assize is something we have seen as an assize...in the kingdom of Jerusalem [the barons] made much better use of the laws and acted on them more surely before the land was lost". Thus a myth was created of an idyllic early 12th century legal system. The barons used this to reinterpret the assise sur la ligece, which Almalric I intended to strengthen the crown, to instead constrain the monarch, particularly with regards to the right of the monarch to remove feudal fiefs without trial. The concomitant loss of the vast majority of rural fiefs led to the barons becoming an urban mercantile class where knowledge of the law was a valuable, well-regarded skill and a career path to higher status.[158] The barons of Jerusalem in the 13th century have been poorly regarded by both contemporary and modern commentators: James of Vitry was disgusted by their superficial rhetoric; Riley-Smith writes of their pedantry and the use of spurious legal justification for political action. For the barons themselves it was this ability to articulate the law that was so prized.[159] The sources of this are the elaborate and impressive treatises by the great baronial jurists from the second half of the 13th century.[160]

The Barons invoked the assise sur la ligece three times in justification of open opposition to arbitrary acts by the king: in 1198, 1229 and 1232. The precedent was set by Ralph of Tiberias when he was accused of attempted regicide. King Aimery had narrowly survived an attempted murder in Tyre by four armed members of the German Crusade. While recovering he became convinced that Ralph was responsible. At a meeting of the High Court Aimery exiled him, ordering his departure from the kingdom within eight days. In response, Ralph devised a defence based on an interpretation of the assise sur la ligece. The defence was that it was an absolute necessity that a case concerning the relationship between a lord and his vassal was judged in court, that vassals were peers bound to give mutual assistance and that vassals should withdraw service from a lord who refused to submit to the court's decision. Ralph's innovation was applying the Assise to the king himself. Aimery refused. His vassals withdrew service from him until 1200 following great words but Ralph still went into banishment. He only returned in 1207 after the king's death. In the later accounts of the jurists, Ralph was credited with a great achievement. He set a precedent in applying the assise to the actions of the crown. This provided him and his peers with justification, a method of resistance and sanctions that could be legally applied. At the same time it is clear that the use of the assise sur la ligece was not effective. Aimery's refusal meant Ralph had still found it necessary to leave the country.[161]

The second time the precedent was consciously followed followed the arrival in the kingdom of Emperor Frederick II in 1228. Three years earlier he had become king-consort when he married Isabella II and immediately claimed the throne of Jerusalem from her father, the king-regent, John of Brienne. Isabella died in the summer of that year, after giving birth to a son. The son, Conrad, was through his mother the king of Jerusalem. As a result, on his arrival Frederick was received as regent.[162] In 1229, Frederick successfully negotiated the return of Jerusalem, lost in 1187, from Egypt and went under the imperial crown in the Holy Sepulchre. Perhaps in a fit of hubris following the acquisition of the city, according to the later baronial jurists, he instructed his bailli Balian Grenier to take control of the Acre possessions of John of Beirut, Walter I Grenier, Walter III of Caesarea, John of Jaffa, Robert of Haifa, Phillip l'asne and John Moriau. These barons invoked the assise sur la ligece and the barons combined force restored their possessions.[163] According to a surviving charter, Alice of Armenia took the same approach to claim the lordship of Toron. Frederick had awarded this to the Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem on its recovery. After this was decided in Alice's favour, a clear baronial victory, the Barons re-entered the Emperor's service. This was the high point of the vassals ability to use the law to resist a monarch infringing what they believed to be their rights.[164] From May 1229 when Frederick II left the Holy Land to defend his Italian and German lands, monarchs were absent—Conrad from 1225 until 1254, his son Conradin until his execution by Charles of Anjou in 1268. Government in Jerusalem had developed in the opposite direction to monarchies in the west. European monarchs such as St Louis, Emperor Frederick and Kind Edward I—contemporary rulers of France, Germany and England respectively—were powerful with bureaucracratic machinary for administration, jurisdiction and legislation. Jerusalem had a royalty without power.[165]

The third invocation of the assise sur la ligece followed the Ibelin's fight for control with an Italian army led by Frederick's viceroy Richard Filangieri in the War of the Lombards. Filangieri besieged John of Beirut's city and convened the High Court to confirm his appointment as regent. When the court demanded he lifted the siege, Filangieri implied John had committed treason and if the court disagreed they should write to the Emperor for final judgement. Tyre, the Hospitallers, the Teutonic Knights and the Pisans supported Filangieri. In opposition were the Ibelins, Acre, the Templars and Genoa. The rebels established a surragate commune, or parliament in Acre.[166] The commune was developed from the cofraternity of St Andrew. It had its own bell and officers. The most important was the major, a position for which John of Beirut was chosen. There was also a deputy major, consuls and captains. Membership was open to all free men. While the commune presented itself as representing the whole country, it did not even represent all of Acre and large numbers still supported the Emperor. After 1236 there is little wriiten evidence of the commune's activities and it is clear that it never adopted governmental functions. The main objective seems to be an attempt to match Filangieri's mandate and resist Frederick II. Ultimately, the barons' motive was the result of Filangieri rejecting the invocation of the Assise. The Barons withdrew their service and attempted to use force but this was ineffective. Filangieri's Italian army was more than capable of resisting. This demonstrated the weakness in the Baron's case. The Assise relied on the king being weak, with a strong force of what John called foreign people, or mercenaries supporting the monarchy the Assise could not be enforced. The baronial jurists such as Phillip of Novara and John of Jaffa do not mention this failure, the events of 1232 or even the balliage of Filangieri. Instead their impressive treatments articulated their political and constitutional ideas rather than the political reality.[167]

When Conrad reached majority in 1242 the Barons finally prevailed, Tyre was captured, and a succession of Ibelin and Cypriot regents followed.[168] Centralised government collapsed while the nobility, military orders and Italian communes took the lead. Three Cypriot Lusignan kings succeeded without the financial or military resources to recover the lost territory. The title of king was even sold to Charles of Anjou, but although he gained power for a short while, he never visited the kingdom. The king of Cyprus fought at Acre until all hope was lost and then returned to his island realm.[169] Cyprus survived the fall of the mainland crusader states and in 1365 Peter I of Cyprus launched the last crusade against Egypt that temporarily captured Alexandria.[170]

Religion

Indigenous Christians shared each other's churches, priests and even took the sacraments together. There is no wriiten evidence that the Franks or local Christians recognised significant religious differences until the 13th century when the jurists repeatedly used phrases such as men not of the rule of Rome.[171] Partly a result of anti-Orthodox sentiment the early crusaders filled ecclesiastical positions in the Orthodox church left vacant with Franks, including the patriarchy of Jerusalem when Simeon II died. The Greek Orthodox Church was considered part of the universal Church, which enabled the replacement of Orthodox bishops by Latin clerics in coastal towns. The first Latin patriarch of Jerusalem, Arnulf of Chocques, ejected the Greek Orthodox monks from the Holy Sepulchre but relented when the miracle of Easter Fire failed in their absence. The appointment of Latin bishops had little effect on the Arabic-speaking Orthodox Christians because the previous bishops were also foreign, from the Byzantine Empire. The Latin bishops used Greeks as coadjutor bishops to administer Syrians and Greeks left without higher clergy. In many villages Latin and Orthodox Christians shared a church. In exceptional political circumstances, Greeks replaced Latin patriarchs in Antioch. Orthodox monasteries were rebuilt and Orthodox monastic life revived. This toleration continued despite an increasingly interventionist papal reaction demonstrated by Jacques de Vitry, Bishop of Acre. The Armenians, Copts, Jacobites, Nestorians and Maronites had greater autonomy. As they were not in communion with Rome they could retain their own bishops without a conflict of authority. Around 1181 Aimery of Limoges, Patriarch of Antioch, managed to bring the Maronites into communion with Rome, establishing a precedent for the Uniate Churches.[172]

That religion prevented assimilation is evidenced by the Franks' discriminatory laws against Jews and Muslims. They were banned from living in Jerusalem and sexual relations between Muslims and Christians were punished (at leat de jure) by mutilation. Some mosques were converted into Christian churches, but the Franks did not force Muslims to convert to Christianity. Frankish lords were particularly reluctant, because conversion would have ended the Muslim peasants' servile status. The Muslims were permitted to pray in public and their pilgrimages to Mecca continued.[173] The Samaritans' annual Passover festival attracted visitors from beyond the kingdom's borders.[174]

Communes

One Frankish weakness was the lack of sea-power. This was addressed by the purchase of naval resources from the Italian maritime republics of Pisa, Venice and Genoa.[175] These republics were enthusiastic crusaders from the early 11th century whose commercial wealth secured the financial base of the Franks. In return these cities, and others such as Amalfi, Barcelona and Marseilles, received commercial rights and access to Eastern markets. Over time this developed into colonial communities with property and jurisdictional rights.[176]

Largely located in the ports of Acre, Tyre, Tripoli and Sidon, communes of Italians, Provençals and Catalans had distinct cultural characteristics and exerted significant political power. Separate from the Frankish nobles or burgesses, the communes were autonomous political entities closely linked to their towns of origin. This gave them the ability to monopolise foreign trade and almost all banking and shipping in the kingdom of Jerusalem. Their parent cities' naval support was essential for the crusader states. Every opportunity to extend trade privileges was taken. One example saw the Venetians receiving one-third of Tyre and its territories, and exemption from all taxes, after Venice participated in the successful 1124 siege of the city. Despite all efforts, the Syrian and Palestinian ports were unable to replace Alexandria and Constantinople as the primary centres of commerce in the region. Instead, the communes competed with the monarchs and each other to maintain economic advantage. Power derived from the support of the communards' home cities rather than their number, which never reached more than hundreds. Thus, by the middle of the 13th century, the rulers of the communes were barely required to recognise the authority of the crusaders and divided Acre into several fortified miniature republics.[177][178]

Military orders

The crusaders habitually followed the customs of their Western European homelands and there were very few cultural innovations in the crusader states. Three notable exceptions to this were the military orders, warfare and fortifications.[179] The order of the Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, more commonly known as the Templars, was formed in 1119 with a mission to protect pilgrims in the perilous territory. The founders were a group of knights attached to the Holy Sepulchre. They were formally recognised at the council of Nablus and eventually granted the Al-Aqsa Mosque on the Temple Mount to use as the orders headquarters. This was known to the Franks as Solomon's Temple from which the order's name derives. The founding leaders, Hugues de Payens and Godfrey de Saint-Omer travelled to Europe and in 1129 the order was recognised by the Latin Church at the Council of Troyes. Enshrining this in a detailed rule, support, privileges and immunities followed from the papacy. Donations of estates across Western Europe and the Levant enabled the order to provide the crusader states with troops, funding, loans and luxury accommodation for travellers.[180]

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem were more commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller. The order began with the operation of an Amalfi funded pilgrim hospital in Jerusalem during the 1080s. After the arrival of the early crusaders they started receiving generous donations both locally and in the west. In 1113 the order that moved from a lay organisation to a religious one was recognised by the pope. It grew into an enormous concern with extensive estates in Italy, Catalonia and Southern France. The income from these provided funding for hundreds of beds serving patients from all religions and genders. By 1126 a military dimension had been added and members formed part of the army from Jerusalem that attacked Damascus.[181]