Fourth Council of Constantinople (Catholic Church)

The Fourth Council of Constantinople was the eighth ecumenical council of the Catholic Church held in Constantinople from October 5, 869, to February 28, 870. It included 102 bishops, three papal legates, and four patriarchs.[1] The Council met in ten sessions from October 869 to February 870 and issued 27 canons.

- For the Eastern Orthodox synod (879–880), see Fourth Council of Constantinople (Eastern Orthodox).

| Fourth Council of Constantinople (869–870) | |

|---|---|

Fourth Council of Constantinople (869-870) | |

| Date | 869–870 |

| Accepted by | Catholic Church |

Previous council | Second Council of Nicaea |

Next council | First Council of the Lateran |

| Convoked by | Emperor Basil I and Pope Adrian II |

| President | papal legates |

| Attendance | 20–25 (first session 869), 102 (last session 870) |

| Topics | Photius' patriarchate |

Documents and statements | Deposition of Photius, 27 canons |

| Chronological list of ecumenical councils | |

| Part of a series on |

| Ecumenical councils of the Catholic Church |

|---|

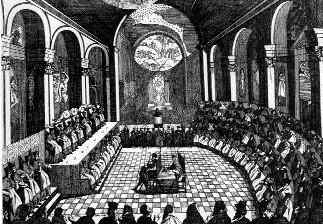

Renaissance depiction of the Council of Trent |

| Antiquity (c. 50 – 451) |

| Early Middle Ages (553–870) |

| High and Late Middle Ages (1122–1517) |

| Modernity (1545–1965) |

|

|

The council was called by Emperor Basil I the Macedonian and Pope Adrian II.[2] It deposed Photios, a layman who had been appointed as Patriarch of Constantinople, and reinstated his predecessor Ignatius.

The Council also reaffirmed the decisions of the Second Council of Nicaea in support of icons and holy images and required the image of Christ to have veneration equal with that of the gospel book.[3]

A later council, the Greek Fourth Council of Constantinople, was held after Photios had been reinstated on the order of the emperor. Today, the Catholic Church recognizes the council in 869–870 as "Constantinople IV", while the Eastern Orthodox Churches recognize the councils in 879–880 as "Constantinople IV" and revere Photios as a saint. At the time that these councils were being held, this division was not yet clear.[4] These two councils represent a growing divide between East and West. The previous seven ecumenical councils are recognized as ecumenical and authoritative by both Eastern Orthodox and Catholic Christians. These kinds of differences led eventually to the East–West Schism of 1054.

Background

With the coronation of Charlemagne by Pope Leo III in 800, the papacy had acquired a new protector in the West. This freed the pontiffs to some degree from the power of the emperor in Constantinople but it also led to a schism, because the emperors and patriarchs of Constantinople interpreted themselves as the true descendants of the Roman Empire.

After the Byzantine emperor summarily dismissed St Ignatius of Constantinople as patriarch of that city, Pope Nicholas I refused to recognize his successor Patriarch Photios I of Constantinople. Photios, in turn, attacked the pope as a heretic, because he kept the filioque in the creed, which referred to the Holy Spirit proceeding from God the Father and the Son. The Council condemned Photius, who questioned the legality of the papal delegates presiding over the Council and ended the schism.

Photian schism

In 858, Photius, a noble layman from a local family, was appointed Patriarch of Constantinople, the most senior episcopal position save only that of Rome. Emperor Michael III had deposed the previous patriarch, Ignatius. Ignatius refused to abdicate, setting up a power struggle between the Emperor and Pope Nicholas I. The 869–870 Council condemned Photius and deposed him as patriarch and reinstated his predecessor Ignatius.[5] It also ranked Constantinople before the other three Eastern patriarchates of Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem.

Support for icons and holy images

One of the key elements of the Council was the reaffirmation of the decisions of the Second Council of Nicaea in support of icons and holy images. The council thus helped stamp out any remaining embers of Byzantine iconoclasm. Specifically, its third Canon required the image of Christ to have veneration equal with that of the gospel book:[6]

We decree that the sacred image of our Lord Jesus Christ, the liberator and Savior of all people, must be venerated with the same honor as is given the book of the holy Gospels. For as through the language of the words contained in this book all can reach salvation, so, due to the action which these images exercise by their colors, all wise and simple alike, can derive profit from them. For what speech conveys in words, pictures announce and bring out in colors.

The council also encouraged the veneration of the images of the Virgin Mary, angels and saints:[3]

If anyone does not venerate the image of Christ our Lord, let him be deprived of seeing him in glory at his second coming. The image of his all pure Mother and the images of the holy angels as well as the images of all the saints are equally the object of our homage and veneration.

Notes

- Catholic Encyclopedia

- "Photius." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- Steven Bigham, 1995 Image of God the Father in Orthodox Theology and Iconography ISBN 1-879038-15-3 page 41

- Karl Rahner, 2004 Encyclopedia of theology ISBN 0-86012-006-6 pages 300

- Karl Rahner, 2004 Encyclopedia of theology ISBN 0-86012-006-6 pages 389

- Gesa Elsbeth Thiessen, 2005 Theological aesthetics ISBN 0-8028-2888-4 page 65

References

- Cross, F. L. (ed.). The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press (2005).

- Dvornik, Francis (1948). The Photian Schism: History and Legend. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Siecienski, Anthony Edward (2010). The Filioque: History of a Doctrinal Controversy. Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)