Jean-Baptiste Kléber

Jean-Baptiste Kléber (IPA: [ʒɑ̃ batist klebɛʁ]) (9 March 1753 – 14 June 1800) was a French general during the French Revolutionary Wars. After having served one year in the French Royal Army, he entered Habsburg service seven years later. But his plebeian ancestry hindered his opportunities. Eventually, he volunteered for the French Army in 1792 and quickly rose through the ranks.

Jean-Baptiste Kléber | |

|---|---|

_-_Nationalmuseum_-_24145.tif.jpg) | |

| Born | 9 March 1753 Strasbourg, France |

| Died | 14 June 1800 (aged 47) Cairo, Egypt |

| Buried | Place Kléber, Strasbourg, France |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | French Royal Army Imperial Army French Revolutionary Army |

| Years of service | 1769–1770 (France) 1777–1783 (HRE) 1792–1800 (France) |

| Rank | General de Division |

| Unit | 1st Hussar Regiment Regiment Kaunitz |

| Commands held | 4th Haute-Rhin Battalion Army of Sambre-et-Meuse Army of the Orient |

| Battles/wars | War of the Bavarian Succession French Revolutionary War

|

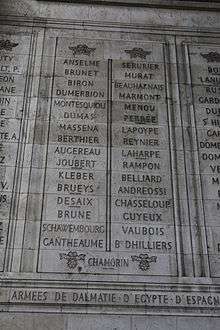

| Awards | Inscription on the Arc de Triomphe (Southern Pillar, Column 23) |

Kléber served in the Rhineland during the War of the First Coalition, and also suppressed the Vendée Revolt. He retired to private life in the peaceful interim after the Treaty of Campo Formio, but returned to military service to accompany Napoleon in the Egyptian Campaign in 1798–99. When Napoleon left Egypt to return to Paris, he appointed Kléber as commander of the French forces. He was assassinated by a student in Cairo in 1800.

A trained architect, Kléber, in times of peace, designed a number of buildings.[1]

Biography

Early career

Kléber was born in Strasbourg, where his father worked as a master builder. He briefly engaged in 1769 in the 1st Hussar Regiment, but resigned to study, from 1770 to 1774, architecture, partly in Paris with Jean Chalgrin. His opportune assistance to two German nobles in a tavern brawl obtained for him nomination to the military school of Munich. From this education, he obtained a commission in the Kaunitz regiment of the Imperial army, he took part in the War of the Bavarian Succession, but did not see major engagements, as he was stationed alternately in the garrisons of Mons, Mechelen, and Luxembourg in the Austrian Netherlands. He resigned his commission in 1783 on finding his humble birth hindered his chances for promotion.[2]

On returning to France he received the appointment of inspector of public buildings at Belfort, where he studied fortification and military science.

French Revolutionary Wars

In 1792 he enlisted in the Haut-Rhin volunteers. Thanks to his military knowledge, he at once gained election as adjutant and soon afterward as lieutenant-colonel.[2] At the defense of Mainz (July 1793) he so distinguished himself that though disgraced along with the rest of the garrison and imprisoned, he promptly won reinstatement, and became in August 1793 a général de brigade. He won considerable distinction in the suppression of the Vendéans, and two months later gained promotion to général de division. In these operations began his intimacy with Marceau, with whom he defeated the Royalists at Le Mans and Savenay. When he openly expressed his opinion that the Vendéans merited lenient measures, the authorities recalled him; but re-instated him once more in April 1794 and sent him to the Armée de Sambre-et-Meuse.[2]

.jpg)

He displayed his skill and bravery in the numerous actions around Charleroi, and especially in the crowning victory of Fleurus (26 June 1794), after which in the winter of 1794 – 1795 he besieged Mainz. In 1795, and again in 1796, he held the chief command of an army temporarily, but declined a permanent appointment as commander-in-chief. On 13 October 1795 he fought a brilliant rearguard action at the bridge of Neuwied, and in the offensive campaign of 1796, he served as Jourdan's most active and successful lieutenant, with his victory at Siegburg on 1 June that year enabling Jourdan to get the bulk of the French force across the Rhine.[2]

Egyptian campaign

After the retreat to the Rhine, he again declined a chief command and withdrew into private life early in 1798. He accepted a division in the expedition to Egypt under Bonaparte, but suffered a wound in the head at Alexandria in the first engagement, which prevented his taking any further part in the campaign of the Pyramids, and caused his appointment as governor of Alexandria. In the Syrian campaign of 1799, however, he commanded the vanguard, took El-Arish, Gaza, and Jaffa, and won the great victory of Mount Tabor on 15–16 April 1799.[2]

When Napoleon returned to France towards the end of 1799, he left Kléber in command of the French forces.[3] In this capacity, seeing no hope of bringing his army back to France or of consolidating his conquests, he negotiated the Convention of El-Arish (24 January 1800) with Commodore Sidney Smith, winning the right to an honorable evacuation of the French army.[3] When Admiral Lord Keith refused to ratify the terms, Kléber attacked the Turks at the Battle of Heliopolis.[3] Although he had only 10,000 men against 60,000 Turks, Kléber's forces utterly defeated the Turks on 20 March 1800. He then re-took Cairo, which had revolted against French rule.[2]

Kléber, son of an operative mason and a prominent freemason himself, was attestedly instrumental in bringing freemasonry to Egypt. While he was negotiating with Sidney Smith in January 1800, Kléber opened a masonic temple in Cairo and thus created the Isis lodge (La Loge Isis), serving as its first master.[4][5]

Assassination

Shortly after these victories, while Kléber was walking in the garden of the palace of Alfi bika, he was knifed by Soleyman El-Halaby, an Arab Syrian[6] student living in Egypt. The assassin appeared to be begging from Kléber, but then took his hand and stabbed him in the heart, stomach, left arm, and right cheek, before running away to hide near the palace. He was soon caught, with the dagger which he had used to kill Kléber, and was later executed. The assassination happened in Cairo on 14 June 1800, coincidentally the same day on which his friend and comrade Desaix fell at Marengo. The assassin's right arm was burned off, and he was impaled in a public square in Cairo and left for several hours to die. Suleiman's skull was shipped to France and used to teach French medical students what the French authorities claimed was the bump of "crime" and "fanaticism".[7]

Burial

After his assassination, Kléber's embalmed body was repatriated to France.[8] Fearing that his tomb would become a symbol of Republicanism, Napoleon ordered it held at the Château d'If, on an island near Marseilles. It stayed there for 18 years until Louis XVIII granted Kléber a burial place in his home town of Strasbourg.[9] He was buried on 15 December 1838 below his statue located in the center of Place Kléber. His heart is in an urn in the caveau of the Governors beneath the altar of the Saint Louis Chapel in Les Invalides, Paris. Kléber's name is inscribed in column 23 on the southern pillar of the Arc de Triomphe.

Assessment

Kléber emerged as undoubtedly one of the greatest generals of the French revolutionary epoch. Though he distrusted his powers and declined the responsibility of supreme command, there is nothing in his career to show that he would have been unequal to it. As a second-in-command no general of his time excelled him. His conduct of affairs in Egypt, at a time when the treasury was empty and the troops were discontented for want of pay, shows that his powers as an administrator were little – if at all – inferior to those he possessed as a general.[2]

Kléber the architect

Between 1784 and 1792, Kléber designed a number of buildings both on public and private commission. Perhaps the most notable is the current town hall of Thann, Haut-Rhin (1787–1793), which was originally designed as a hospital but turned into an administrative building before its completion.[10] Other surviving buildings are the château of Grandvillars (often erroneously spelled "Granvillars"), built around 1790[11] and the canoness houses of the Benedictine abbey of Masevaux (1781–1790). Nine of these houses had been planned but due to the French Revolution, only seven were built.[12] The Musée historique de Strasbourg features a room dedicated to Jean-Baptiste Kléber that also displays a number of his sketches and architectural designs.

See also

- Lycée Kléber

- Place Kléber

- Kléber (Paris Métro)

- Kléber (train)

- Manfred Stern, Austrian-born Soviet officer who gained fame in the Spanish Civil War under the pseudonym "General Kléber"

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jean-Baptiste Kléber. |

- Jensen, Nathan D. "General Jean-Baptiste Kléber". frenchempire.net. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- Chisholm 1911.

- Charles River Editors (2018). Napoleon in Egypt: The History and Legacy of the French Campaign in Egypt and Syria. Charles River Editors. ISBN 978-1718863620.

- Dictionnaire universelle de la Franc-Maçonnerie (Marc de Jode, Monique Cara and Jean-Marc Cara, ed. Larousse , 2011)

- La franc-maçonnerie révélée aux profanes (Pierre Ripert – ed. Presses de Chatelet- 2009)

- Al-Asadi, Khair al-Din. "Digital version, from the Encyclopedia of Aleppo Comparative" (PDF) (in Arabic). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2016.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20091231235534/http://damascus-online.com/se/bio/halabi_suleiman.htm

- Cimetières de France et d’ailleurs (in French)

- Jean Paul Baillard. Kléber après Kléber (1800–2000) – Les pérégrinations posthumes des restes du général Kléber ISBN 2-913302-08-4 (in French)

- "Hôtel de ville de Thann". patrimoine.alsace. Archived from the original on 24 February 2016. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- "Château, puis tréfilerie et usine de petite métallurgie dites le Château". actuacity.com. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- "Abbaye de bénédictines Saint-Léger". actuacity.com. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- Attribution

Further reading

- Philippe Jéhin, Jean-Baptiste Kléber : le lion indomptable : 1753-1800, Éditions Vent d'Est 2012, ISBN 979-10-90826-06-9

- Auguste Echard: J.-B. Kléber : un fils de l'Alsace, Charavay Frères Éditeurs, Paris, 1883 (sic) online version