Proclamation of the Republic (Brazil)

The Proclamation of the Republic (Portuguese: Proclamação da República do Brasil) was a military coup d'état that established the First Brazilian Republic on 15 November 1889. It overthrew the constitutional monarchy of the Empire of Brazil and ended the reign of Emperor Pedro II.

| Proclamation of the Republic (Brazil) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

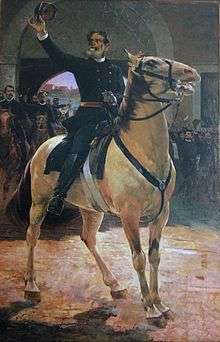

The proclamation of the Republic took place in Rio de Janeiro, then capital of the Empire of Brazil, when a group of military officers of the Brazilian Army, led by Marshal Deodoro da Fonseca, staged a coup d'état without the use of violence, deposing Emperor Pedro II and the President of the Council of Ministers of the Empire, the Viscount of Ouro Preto.

A provisional government was established that same day, 15 November, with Marshal Deodoro da Fonseca as President of the Republic and head of the interim Government.

Background

From the 1870s, as a consequence of the Paraguayan War (also called the War of the Triple Alliance, 1864-1870), the idea of some sectors of the elite was altered to change the current political regime. Factors that influenced this movement:

- The Emperor Pedro II had no male children, only daughters. The throne would be occupied, after his death, by his eldest daughter, Isabel, Princess Imperial of Brazil, married to a Frenchman, Prince Gaston, Count of Eu, which generated the fear in part of the population that the country would be ruled by a foreigner.

- The resentment of the agrarian elite for the abolition of slavery, which they considered to be a personal desire of the imperial family and not of the people.

- The growth of the positivist and republican idea of Auguste Comte among the members of the Brazilian Army and its resentment with the monarchy by delicate military questions.

Political situation in 1889

The Imperial Government, through the 37th and last ministerial cabinet, was inaugurated on 7 June 1889, under the command of the President of the Council of Ministers of the Empire, Afonso Celso de Assis Figueiredo, the Viscount of Ouro Preto of the Liberal Party, perceiving the difficult political situation in which he was present, presented in a last desperate attempt to save the Empire to the Chamber of Deputies, a program of political reforms which included, among others, the following measures: greater autonomy administrative freedom for the provinces (Federal system), universal suffrage, freedom of education, reduction of prerogatives of the Council of State and non-lifelong mandates for the Imperial Senate. The proposals of the Viscount de Ouro Preto aimed at preserving the monarchical regime in the country, but were vetoed by the majority of deputies of conservative tendency that controlled the General Chamber. On 15 November 1889, the republic was proclaimed by the positivist militaries supported by the agrarian elite resented for not being compensated for the abolition of slavery.

Loss of prestige of the monarchy

There were many factors that led the Empire to lose the support of its economic and military bases. On the part of the conservative groups, by the serious friction with the Catholic Church; by the loss of the political support of the great landowners due to the abolition of slavery, which occurred in 1888 without the compensation of the slaveholders.

On the part of the progressive groups, there was the criticism that the monarchy had maintained until very late, the slavery in the country. Progressives also criticized the absence of initiatives aimed at the economic, political or social development of the country, the maintenance of a political regime of caste and census voting, that is, based on the annual income of the people, the absence of a system of universal education, high rates of illiteracy and misery, and the political withdrawal of Brazil from all other countries on the continent, which were republican.

Thus, at the same time that imperial legitimacy declined, the republican proposal - perceived as meaning social progress - gained space. However, it is important to note that the Emperor's legitimacy was distinct from that of the imperial regime: While, on the one hand, the population generally respected and loved Emperor Pedro II, on the other hand, had less and less the Empire. In this sense, it was a common voice at the time that there would be no third reign, that is, the monarchy would not continue to exist after the death of Pedro II, whether due to the lack of political support of the monarchical regime itself or due to the concerns about the succession by a woman, Princess Isabel, in a still very misogynistic society. The prince consort, husband of Princess Isabel, the French Count d'Eu, was hard of hearing, he spoke with a French accent, and, moreover, he owned slums in Rio, for which he supposedly collected exorbitant rents from poor people. It was feared that, when Isabel ascended the throne, Brazil would be de facto ruled by a foreigner.

Although the phrase of Aristides Lobo (journalist and republican leader from São Paulo, later made provisional minister), "The people witnessed bestialized" to the proclamation of the republic, has entered into history, more recent historical research has given another version to the acceptance of the republic among the Brazilian people. This is the case of the thesis defended by Maria Tereza Chaves de Mello (A República Consentida, FGV Publisher, EDUR, 2007), which indicates that the republic, before and after the proclamation, was popularly seen as a political regime that would bring about development, in a broad sense, to the country, although the common people did not want to change the regime of government.

Abolitionist issue

The abolitionist question had been imposed since the abolition of the slave trade in 1850, finding resistance among the country's traditional agrarian elites. In view of the measures adopted by the Empire for the gradual extinction of the slave regime, due to the repercussion of the unsuccessful experience in the United States of general liberation of the slaves having led that country to civil war, these elites demanded from the State reparations proportional to the total price they had paid by slaves to be liberated by law. These indemnities would be paid with an external loan.

With the enactment of the Golden Law (1888), and by failing to indemnify these large landowners, the Empire lost its last pillar of support. Called "Republican last minute" or Republican May 13, former slaveholders joined the Republican cause, not because of a sentiment, but as a "revenge" against the monarchy.

In the view of the progressives, the Empire of Brazil was very slow in the solution of the so-called "Servant Question", which undoubtedly undermined its legitimacy over the years. Even the adherence of the former slaveholders, who were not compensated, to the republican cause, shows how much the imperial regime was tied to slavery.

Thus, shortly after Princess Isabel signed the Golden Law, João Maurício Vanderlei, Baron of Cotejipe, the only senator of the empire who voted against the project of abolishing slavery, prophesied: "His Highness redeemed a race but lost the throne". Despite this, the republican and black journalist José do Patrocínio threw himself at the Princess's feet and named her "redeemer".

Religious issue

From the colonial period, the Catholic Church, as institution, was submitted to the state. This was maintained after independence and meant, among other things, that no order of the Pope could be enforced in Brazil without having been previously approved by the Emperor (Regal Benefict). In 1872, Vital Maria Gonçalves de Oliveira and Antônio de Macedo Costa, bishops of Olinda and Belém respectively, decided to follow on their own the orders of Pope Pius IX, which excluded the Freemasons from the church. As members of high influence in monarchic Brazil were Freemasons (some books also mention Dom Pedro II himself as Mason), the bull was not ratified.

The bishops refused to obey the law and were arrested. In 1875, thanks to the intervention of the Duke of Caxias, the bishops received imperial pardon and were released. However, in the episode, the image of the Empire was worn next to the Catholic Church. And this was an aggravating factor in the crisis of the monarchy, since the support of the Catholic Church to the monarchy was always essential to its subsistence.

Military issue

The military of the Brazilian Army was dissatisfied with the ban imposed by the monarchy, by which its officers could not express themselves in the press without the prior authorization of the Minister of War. The military did not have autonomy of decision-making on the defense of the territory, being subject to the orders of the Emperor and the Cabinet of Ministers, formed by civilians, that they surpassed to the orders of the generals. Thus, in the Empire, most war ministers were civilians.

In addition, often the Brazilian Army soldiers felt discredited and disrespected. On the one hand, the rulers of the empire were civilians, whose selection was extremely elitist and whose formation was bachelora, but that resulted in positions highly paid and valued; On the other hand, the military had a more democratic selection and a more technical formation, but did not result in professional valorization or political, social or economic recognition. Military career promotions were hard to come by and were based on personal criteria rather than on merit and seniority promotions.

The Paraguayan War, in addition to spreading republican ideals, showed the military this devaluation of the professional career, which continued and even intensified after the end of the war. The result was the perception, on the part of the military, that they sacrificed themselves for a regime that little considered them and that gave more attention to the Navy of Brazil. Simultaneously the military suffered a strong positivist influence that spread to the military schools. They became desirous of a strong republic headed by a dictator.

Republican and positivist actions

During the Paraguayan War, the Brazilian military's contact with the reality of its South American neighbors led them to reflect on the relationship between political regimes and social problems. From this, a greater interest for the republican ideal and Brazilian economic and social development began to develop, both among the career military and among the civilians called to fight in the conflict.

Thus, it was no coincidence that Republican propaganda had, by its initial mark, the publication of the Republican Manifesto in 1870 (the year in which the Paraguayan War ended), followed by the Itu Convention in 1873 and the emergence of Republican clubs, which Have multiplied, since then, by the main centers in the country.

In addition, various groups were heavily influenced by Freemasonry (Deodoro da Fonseca was a Freemason, as well as his entire ministry) and Auguste Comte's positivism, especially after 1881, when the Positivist Church of Brazil emerged. Its directors, Miguel Lemos and Raimundo Teixeira Mendes, initiated a strong abolitionist and republican campaign.

Republican propaganda was carried out by what were later called "historic Republicans" (as opposed to those who became Republicans only after November 15, called "Nov. 16 Republicans").

The ideas of many of the republicans were published by the newspaper The Republic. According to some researchers, Republicans were divided into two main streams:

- The evolutionists, who admitted that the proclamation of the republic was inevitable, not justifying an armed struggle;

- The revolutionists, who defended the possibility of taking up arms to conquer it, with popular mobilization and with social and economic reforms.

Although there were differences between each of these groups as regards the political strategies for the implementation of the republic and also the substantive content of the regime to be established, the general idea common to both groups was that the republic should be a progressive, opposed to the "exhausted" monarchy. Thus, the proposal of the new regime was of a revolutionary social character and not only of a mere exchange of rulers.

Military coup of November 15, 1889

In Rio de Janeiro, Republicans insisted that Marshal Deodoro da Fonseca, a monarchist, head the revolutionary movement that would replace the monarchy with the republic.

After much insistence from the revolutionaries, Deodoro da Fonseca agreed to lead the military movement.

According to historical accounts, on November 15, 1889, commanding a few hundred soldiers moving through the streets of Rio de Janeiro, Marshal Deodoro, as well as a large part of the military, intended only to overthrow the then Chief of the Imperial Cabinet (equivalent to the Prime Minister), the Viscount of Ouro Preto. "The main culprits of all this [the proclamation of the Republic] are Count of Eu and the Viscount of Ouro Preto: the last to persecute the Army and the first to consent to this persecution," Deodoro later wrote.[1]

The military coup, which was scheduled for November 20, 1889, had to be anticipated. On the 14th, the conspirators issued a rumor that the government had arrested Benjamin Constant Botelho de Magalhães and Deodoro da Fonseca. Later it was confirmed that it was even rumor. Thus, the revolutionaries anticipated the coup, and in the early hours of November 15, Deodoro was willing to lead the movement of army troops that put an end to the monarchist regime in Brazil.

The conspirators went to the residence of Marshal Deodoro, who was sick with dyspnea, and they finally convinced him to lead the movement. Apparently decisive for Deodoro was to know that, as of November 20, the new President of the Council of Ministers of the Empire would be Silveira Martins, an old rival. Deodoro and Silveira Martins had been enemies since the time when the marshal had served in Rio Grande do Sul, when both fought for the attention of the Baroness of Triunfo, a very beautiful and elegant widow who, according to the reports of the time, had preferred Silveira Martins. Since then, Silveira Martins did not miss an opportunity to provoke Deodoro from the Senate floor, insinuating that he misused funds and even challenging his effectiveness as a military leader.

In addition, Major Frederico Solon de Sampaio Ribeiro had told Deodoro that an alleged arrest warrant had been issued against him, a false argument that finally convinced the old marshal to proclaim the Republic on the 16th and to exile the Imperial Family by night, in order to avoid an eventual popular commotion.

.jpg)

Convinced that he would be arrested by the imperial government, Deodoro left his residence at dawn on November 15, crossed the Campo de Santana, and on the other side of the park called the soldiers of the battalion there, where the Duke de Caxias Palace is now located, to rebel against the government. They offered a horse to the marshal, who rode on it, and, according to testimony, took off his hat and proclaimed "Long live the Republic!" Then he alighted, crossed the park again, and returned to his residence. The demonstration continued with a parade of troops on Direita street until the Imperial Palace. Recent studies indicate that Marshal Deodoro shouted "Long live His Majesty the Emperor!" however, for until then he was convinced to testify to the cabinet, not to proclaim the republic, and only did so when it was falsely told that his rival would take the Position.

The rioters occupied the headquarters of Rio de Janeiro and then the Ministry of War. They deposed the Cabinet and arrested their president, Afonso Celso de Assis Figueiredo, Viscount Ouro Preto.

In the Imperial Palace, Viscount de Ouro Preto, the president of the cabinet (prime minister), had been trying to resist asking the commander of the local detachment and responsible for the security of the Imperial Palace, General Floriano Peixoto, to confront the mutineers, explaining to General Floriano Peixoto that there were enough legalist troops on the scene to defeat the rioters. The Viscount of Ouro Preto reminded Floriano Peixoto that he had faced much more numerous troops in the Paraguayan War. However, General Floriano Peixoto refused to obey the orders given by the Viscount of Ouro Preto and thus justified his insubordination, responding to the Viscount of Ouro Preto:

Yes, but there (in Paraguay) we had enemies in front and here we are all Brazilians!

— Floriano Peixoto[2]

Then, adhering to the republican movement, Floriano Peixoto gave a prison sentence to the head of government.

The only one wounded in the episode of the proclamation of the republic was the Baron of Ladario, Minister of the Navy, who resisted the arrest warrant given by the mutineers and was shot. It is said that Deodoro did not address criticism of the Emperor Pedro II and that he hesitated in his words. Despite this, it was known that Deodoro da Fonseca was with Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin Constant at his side and that there were some civilian republican leaders at that time. But Deodoro favored the republic only after the death of the Emperor: "I would like to carry the coffin of the Emperor," he said.

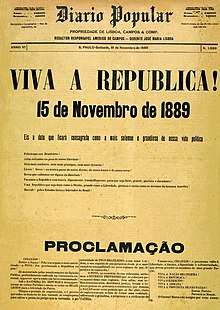

On the afternoon of November 15, at the City Hall of Rio de Janeiro, the Republic was solemnly proclaimed.

At night, in the Municipal Council of the Neutral Municipality, Rio de Janeiro, José do Patrocínio drafted the official proclamation of the Republic of the United States of Brazil, approved without a vote. The text went to the newspaper charts that supported the cause, and, only the next day, November 16, was announced to the people the change of the political regime of Brazil.

Pedro II, who was in Petrópolis, returned to Rio de Janeiro. Thinking that the aim of the revolutionaries was only to replace the office of Ouro Preto, the Emperor still tried to organize another ministerial cabinet, under the chairmanship of the councilor José Antônio Saraiva. The Emperor, in Petropolis, was informed and decided to go down to the Court. Upon learning of the coup, the Emperor acknowledged the fall of the Ouro Preto Cabinet and sought to announce a new name to replace the Viscount of Ouro Preto. However, since nothing had been said about Republic until then, the most exalted Republicans spread the rumor that the Emperor had chosen Gaspar Silveira Martins, political enemy of Deodoro da Fonseca since Rio Grande do Sul, to be the new head of government. Deodoro da Fonseca then persuaded himself to join the Republican cause. The Emperor was informed of this and, disillusioned, decided not to offer resistance.

If it is so, it will be my retirement. I have worked too hard and I am tired. I will go rest then.

— Pedro II, Emperor of Brazil

The next day, Major Frederico Solon de Sampaio Ribeiro gave Pedro II a communication, informing him of the proclamation of the republic and ordering his departure for Europe, in order to avoid political upheavals. The Brazilian Imperial Family was exiled in Europe, only being allowed to return to Brazil in 1920 by President Epitácio Pessoa.[3]

Reactions

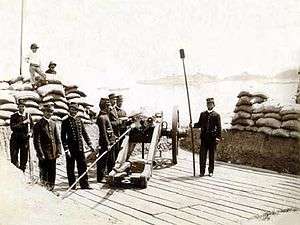

Despite the lack of any will to resist from Pedro II, there was significant monarchist reaction after the fall of the Empire, which was thoroughly repressed.[4] A few examples can be given. On 17 November 1889, upon hearing the news of the Emperor's fall, the 25th Infantry Battalion resisted by attacking the local Republican Club in Desterro (present-day Florianópolis). They were defeated by Republican militias and policemen and several were killed. Others were executed. According to the source, other battalions across the country also unsuccessfully fought against policemen and militias loyal to the Republic.[3] In Rio de Janeiro, then-the Brazilian capital, on 18 November between 30 and 40[5] monarchist soldiers rebelled.[5] Other monarchists rebellions occurred in Rio. On 18 December 1889, the 2nd Artillery Regiment – around 50 men[6] – rebelled in a restorationist attempt.[3] It led the government to ban freedom of the speech and exile or arrest several monarchist politicians.[3] Another far more serious monarchist rebellion occurred on 14 January 1890,[5] when 1 Cavalry Regiment, 2 Infantry Regiments and 1 Artillery Battalion[5] attempted to overthrown the republic[5] It had more than 100 casualties, and 21 officers and soldiers who took part of it were executed and more monarchist politicians were arrested.[5]

.jpg)

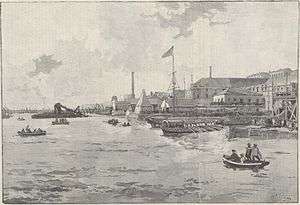

In 1891 happened in Rio de Janeiro the so-called Revolta da Armada, a rebellion movement promoted by units of the Brazilian Navy against the dictatorial government of Deodoro da Fonseca, supposedly supported by the monarchist opposition to the recent installation of the republic, in which the navy threatened to bomb the federal capital.[7][8] The Navy, still resented by circumstances and outcomes of the coup that had put an end to the monarchy in Brazil.[7] Again between 1893 and 1894, before the dictatorship and the rights curtailment promoted by the government of Floriano Peixoto, the navy monarchist rebelled against the government. In that episode the Republicans had aid of the American navy to defeat the monarchists.[9]

A major civil war, that occurred from 1893 to 1895, between several monarchists and even republicans led by the monarchists leaders Gaspar da Silveira Martins,[10] Custódio de Melo[11] and Saldanha Da Gama[11] against the republican government resulted in the death of 10,000 men.[11]

The War of Canudos was a conflict between the state of Brazil and a group of some 30,000 settlers who had founded their own community in the Northeastern state of Bahia, named Canudos. After a number of unsuccessful attempts at military suppression, it came to a brutal end in October 1897, when a large Brazilian army force overran the village and killed nearly all the inhabitants. This was the deadliest civil war in Brazilian history.[11][3] The community of Canudos was led by Antonio Conselheiro, in the interior of the state of Bahia against the great farmers supported by the Republican army. Rumors were created that Canudos was armed to attack neighboring towns and leave for the capital to depose the republican government and reinstall the monarchy. Only 300 survived the massacre caused by Republican Army troops in 1897[11] As a matter of comparison, the 1964–1985 Military dictatorship led to the death of 380 people[12]

An event little known, but very interesting was the Revolt of Ribeirãozinho. Also called the Ribeirãozinho Revolution, it was a conservative movement of the early twentieth century that occurred in the city of Ribeirãozinho (now Taquaritinga), in São Paulo, and whose fundamental objective was the restoration of the monarchy and the coronation of Prince Luiz of Orléans-Braganza, son of Isabel, Princess Imperial of Brazil. Unhappy with the First Brazilian Republic, the São Paulo monarchists had planned an uprising that was supposed to take place on August 23, 1902, and which was to topple then President Campos Sales. In fact, the uprising had only been carried out in Ribeirãozinho and Espírito Santo do Pinhal, a neighboring town. This attempt to restore the monarchy lasted one day.[13]

Controversies

.svg.png)

It is possible to challenge the legitimacy of the republic in Brazil from different angles.

From the point of view of the Criminal Code of the Empire of Brazil, sanctioned on December 16, 1830, the crime committed by the Republicans was:

"Article 87: To try directly and by deeds to dethrone the Emperor, to deprive him of all or part of his constitutional authority, or to alter the legitimate order of succession, and imprisonment for five to fifteen years. Crime to be consummated: Fees of life imprisonment with work in the maximum degree, imprisonment with work for twenty years in the middle, and for a minimum of ten years.

.jpg)

The Viscount of Ouro Preto, deposed on November 15, understood that the proclamation of the republic had been a mistake and that the reign of Pedro II had been good, and this was expressed in his book "Advent of the Military Dictatorship in Brazil":

The Empire was not the ruin. It was conservation and progress. For half a century, it maintained intact, tranquil and united colossal territory. The Empire converted a backward and little populous country into great and strong nationality, the first South American power, considered and respected throughout the civilized world. To the efforts of the Empire, mainly, three neighbors owed the disappearance of the most cruel and demeaning despotism. The Empire effectively abolished the death penalty, extinguished slavery, gave Brazil immortal glories, internal peace, order, security, and, more than anything else, individual liberty as there has never been in any country. What are the faults or crimes of Dom Pedro II, who in almost fifty years of his reign never persecuted anyone, never remembered an ingratitude, never avenged an injury, ready always to forgive, forget and benefit? What errors have been made that made him worthy of deposition and exile when, old and sick, he ought to count on the respect and veneration of his fellow citizens? The Brazilian republic, as proclaimed, is a work of iniquity. The republic has risen on the corsets of the mutinous soldiery, comes from a criminal origin, was carried out by means of an attack unprecedented in history and will have an ephemeral existence!

— Viscount of Ouro Preto

The movement of November 15, 1889 was not the first to seek the republic, although it was the only truly successful one, and according to some versions it would have had the support of both national and regional elites:

- In 1788-1789, the conspiracy called Inconfidência Mineira sought not only independence but also the proclamation of a republic in the Captaincy of Minas Gerais, followed by a series of political, economic and social reforms;

- In 1817, through the Pernambucan revolt - the only separatist movement of the colonial period that surpassed the conspiratorial phase and reached the revolutionary process of seizure of power - Pernambuco had provisional government for 75 days;

- In 1824, Pernambuco and other Northeastern states (territories that formerly belonged to that province) created the pro-independence movement known as the Republican Equatorial Confederation of the Equator, considered the main reaction against the authoritarian tendency and centralizing policy of Emperor Pedro I's government;

- In 1839, in the wake of the Ragamuffin War, the Riograndense Republic and the Juliana Republic were proclaimed respectively in Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina.

Although there was no popular participation in the movement that ended with the monarchist regime and implanted the republic, there were also no popular demonstrations of support for the monarchy or repudiation of the new regime, although there was clear adoration and commotion toward the Emperor who was beloved and admired even by the republicans. The people seemed indifferent to the political course of the nation.

.jpg)

Some researchers argue that, if the monarchy were popular, there would be moves against the republic then beyond the Canudos War and the Revolta da Armada. However, according to other researchers, what would have happened was a growing awareness about the new regime and the indifference by the most different sectors of Brazilian society. An opposing version is given by the researcher, Maria de Lourdes Monaco Janoti, in the book "Os Subversivos da República", in which she recounts the fear that the Republicans had in the first decades of the republic, regarding a possible restoration of the monarchy in Brazil. Maria Janoti also shows in her book the strong Republican repression of any attempt to organize monarchist political groups at that time.

In relation to the lack of popular participation in the November 15 movement, a document that had great repercussions was the article by Aristides Lobo, who was an eyewitness to the proclamation of the Republic, in the Popular Diário de São Paulo, on November 18, in which Said:

For now, the color of government is purely military and should be so. The fact was theirs, of them only because the collaboration of the civil element was almost null. The people watched it all bestialized, astonished, without knowing what it meant. Many seriously believed to be seeing a parade!

— Aristides lobo

At the meeting at the house of Deodoro, on the night of November 15, 1889, it was decided that a popular referendum would be held, so that the Brazilian people would vote for the republic, or not. However, this plebiscite only occurred 104 years later, as determined by article two of the Transitional Constitutional Provisions Act of 1988.

References

- What really happened in the Proclamation of the Republic. By Paulo Gomes Lacerda

- OURO PRETO, Visconde de, Advento da ditadura militar no Brasil, Imprimiere F. Pichon, Paris, 1891

- Mônaco Janotti, Maria de Lourdes (1986). Os Subversivos da República (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Brasiliense.

- Salles 1996, p. 194.

- Topik, Steven C. (2009). Comércio e canhoneiras: Brasil e Estados Unidos na Era dos Impérios (1889–97) (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.

- Silva, Hélio (2005). 1889: A República não esperou o amanhecer (in Portuguese). Porto Alegre: L&PM.

- Smallman; Shall C. Fear & Memory in the Brazilian Army & Society, 1889–1954 The University of North Carolina Press 2002 ISBN 0807853593 Page 20 2nd paragraph

- Joseph Smith; Brazil and the United States: Convergence and Divergence University of Georgia Press 2010, page 38, 2nd paragraph

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-02-19. Retrieved 2011-12-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Brandão, Adelino (1996). Paraíso perdido: Euclides da Cunha : vida e obra (in Portuguese). São Paulo: IBRASA.

- Bueno, Eduardo (2003). Brasil: uma História (in Portuguese) (1st ed.). São Paulo: Ática.

- Narloch, Leandro (2009). Guia politicamente incorreto do Brasil (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Leya.

- "The Revolt of Ribeirãozinho and the return of the monarchy". Taquaritinga On-line. 2008-06-21. Archived from the original on 2014-03-05. Retrieved 2017-04-24.