Jacques Pierre Brissot

Jacques Pierre Brissot (15 January 1754 – 31 October 1793), who assumed the name of de Warville (an English version of "d'Ouarville", a hamlet in the village of Lèves where his father owned property),[1] was a leading member of the Girondins during the French Revolution and founder of the abolitionist Society of the Friends of the Blacks. Some sources give his name as Jean Pierre Brissot.

Jacques Pierre Brissot de Warville | |

|---|---|

Brissot portrait by Fouquet (1792) | |

| Member of the National Convention for Eure-et-Loir | |

| In office 20 September 1792 – 30 October 1793 | |

| Preceded by | Étienne Claye |

| Succeeded by | Claude Julien Maras |

| Constituency | Chartres |

| Member of the Legislative Assembly for Seine | |

| In office 1 October 1791 – 19 September 1792 | |

| Succeeded by | Antoine Sergent-Marceau |

| Constituency | Paris |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Jacques Pierre Brissot 15 January 1754 Chartres, Orléanais, France |

| Died | 31 October 1793 (aged 39) Paris, Seine, France |

| Cause of death | Guillotine |

| Resting place | Chapelle Expiatoire, Paris 48.873611°N 2.322778°E |

| Nationality | French |

| Political party | Girondin |

| Spouse(s) | Félicité Dupont

( m. 1759; his d. 1793) |

| Children | Pierre Augustin Félix Edme Augustin Sylvain Jacques Jérôme Anacharsis |

| Alma mater | University of Orléans |

| Profession | Journalist, publisher |

| Signature | |

Biography

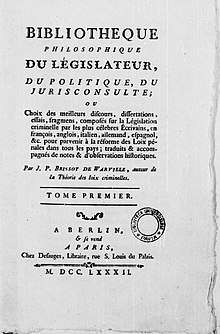

Brissot was born at Chartres, where his father was an innkeeper. He received an education and worked as a law clerk; first in Chartres then in Paris.[2] He later moved to London because he wanted to pursue a literary career. He published many literary articles throughout his time in the British capital. While there, Brissot founded two periodicals that later did not do well and failed.[2] He married Félicité Dupont (1759–1818), who translated English works, including Oliver Goldsmith and Robert Dodsley. They lived in London and had three children. His first works, Théorie des lois criminelles (1781) and Bibliothèque philosophique du législateur (1782), dealt with philosophy of law topics, and showed the deep influence of ethical precepts espoused by Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

In the preface of Théorie des lois criminelles, Brissot explains that he submitted an outline of the book to Voltaire and quotes his answer from 13 April 1778. Théorie des lois criminelles was a plea for penal reform. The pamphlet was considered extremely provocative as it was perceived as opposing the government and the queen. Brissot was imprisoned in the Bastille but was later released in September 1784.[2][3][4]

Brissot became known as a writer and was engaged on the Mercure de France, the Courrier de l'Europe and other papers. Devoted to the cause of humanity, he proposed a plan for the collaboration of all European intellectuals. His newspaper Journal du Lycée de Londres, was to be the organ of their views. The plan was unsuccessful. Soon after his return to Paris, Brissot was placed in the Bastille in 1784 on the charge of having published a pornographic pamphlet Passe-temps de Toinette against the queen. Brissot had a falling out with Catholicism, and wrote about his disagreements with the church's hierarchical system.[5]

After gaining release in four months, Brissot returned to pamphleteering, most notably his 1785 open letter to emperor Joseph II of Austria, Seconde lettre d'un défenseur du peuple a l'Empereur Joseph II, sur son règlement concernant, et principalement sur la révolte des Valaques, which supported the right of subjects to revolt against the misrule of a monarch. Because of the controversy this generated, he went to London for a time.[6]

On this second visit, he became acquainted with some of the leading abolitionists. After returning to Paris in 1788, he founded an anti-slavery group known as Society of the Friends of the Blacks, of which he was president during 1790 and 1791. In 1791, Brissot along with Marquis de Condorcet, Thomas Paine, and Etienne Dumont created a newspaper promoting republicanism titled Le Républicain.[7]

As an agent of the newly formed society, Brissot traveled to the United States in 1788 to visit with abolitionists there. The country had gained independence several years before, but was still creating its final form of government. He also met with members of the constitutional convention in Philadelphia. In 1791 he published his Nouveau Voyage dans les États-Unis de l'Amérique septentrionale (3 vols.). Brissot believed that American ideals could help improve French government. In 1789 he was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[8] At one point, he was interested in emigrating to America with his family. Thomas Jefferson, American ambassador in Paris when he returned, was familiar enough with him to note, "Warville is returned charmed with our country. He is going to carry his wife and children to settle there."[9] However, such an emigration never happened. The rising ferment of revolution engaged Brissot in schemes for progress through political journalism that would make him a household name.[9]

From the outbreak of the Revolution in 1789, Brissot became one of its most vocal supporters. He edited the Patriote français from 1789 to 1793 and took a prominent part in politics.[10] Famous for his speeches at the Jacobin Club, he was elected a member of the municipality of Paris, then of the Legislative Assembly, and later of the National Convention. At the National Convention, Brissot represented Eure-et-Loir.[2]

Shortly thereafter, Brissot began to align himself with the more moderate Girondins, who were often viewed as the 'war party.' The Girondins, or Brissotins as they were often called, were a group of loosely affiliated individuals, many of whom came from Gironde, rather than an organized party with a clear ideology. This group was first led by Brissot.[11] Robespierre loathed the Girondins.[12]

Following the arrest of King Louis XVI on charges of "high treason" and "crimes against the State", there was widespread disagreement on what the fate of the king should be. While many, believing that leaving the King alive increased the chances of a return to monarchy, argued to execute the king by guillotine, Brissot and other Girondins suggested several alternatives in hopes of sparing his life.[13] Brissot and the Girondins championed the idea of keeping him under arrest both as a hostage and as a bargaining chip. Brissot believed that once Louis XVI was executed all of France's foreign negotiating power would be lost, and he also feared a massive royalist rebellion. At one point, many Girondin leaders, including Brissot, called for a national referendum which would enable the citizens to vote on the king's fate.[13] However, the Convention eventually voted for the king's immediate execution, and King Louis XVI was beheaded on January 21, 1793.

Foreign policy

At the time of the Declaration of Pillnitz (27 August 1791), Brissot headed the Legislative Assembly. The declaration was from Austria and Prussia, warning the people of France not to harm Louis XVI or these nations would "militarily intervene" in the politics of France. Threatened by the declaration, Brissot rallied the support of the Legislative Assembly, which subsequently declared war on Austria on 20 April 1792. They wanted to fortify and secure the revolution.[14] This decision was initially disastrous as the French armies were crushed during the first engagements, leading to a major increase in political tensions within the country.

During the Legislative Assembly, Brissot's knowledge of foreign affairs enabled him as member of the diplomatic committee to control much of France's foreign policy during this time. Brissot was a key figure in the declaration of war against Leopold II, the Habsburg Monarchy, the Dutch Republic, and the Kingdom of Great Britain on 1 February 1793. It was also Brissot who characterized these wars as part of revolutionary propaganda.[15]

Arrest and execution

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Brissot, Jacques Pierre. |

Even before the overthrow of King Louis XVI and the founding of the French Republic in August 1792, two principal factions developed among the radicals of the Left: Brissot's more moderate Girondins, and the more radical Montagnards ('the Mountain'). The divisions between the two factions had less to do with ideology than with tactics and personalities. Preceding the King's fall, and then during the first year of the Republic (August 1792-May 1793), affiliates and allies of the Girondins held many positions of power in the new Republic, none more than Brissot. But as the military suffered defeat on the battlefield, and starvation and chaos threatened the countryside, the Girondins were blamed for many of these crises - sometimes for good reason. After the execution of King Louis XVI and the subsequent widening of the war, the Montagnards were able to stir up intense distrust and opposition to the Girondin regime, ultimately inciting their overthrow.

The Encyclopædia Britannica 11th edition, remarked: "Brissot was quick, eager, impetuous, and a man of wide knowledge. However, he was indecisive, and not qualified to struggle against the fierce energies roused by the events of the Revolution."[2]

Brissot's stance on the King's execution, the war with Austria and his moderate views on the Revolution intensified the friction between the Girondins and Montagnards, who allied themselves with disaffected Sans-culottes. Brissot ultimately attempted to rein in the violence and excesses of the Revolution by calling for the reinstatement of the constitutional monarchy that had been established by the Constitution of 1791, a ploy which landed on deaf ears.

In late May 1793, the Montagnards in the Convention, meeting in the Tuileries Palace, called for the removal of the Commission of Twelve. The Convention was further radicalized by the call for the removal and arrest of Brissot and the entire Girondin group made by the Sans-culottes in the Parisian National Guard, which had armed with cannons and surrounded the Convention.[16] When the refusal of the Convention to make such a hasty decision was delivered to the National Guard, François Hanriot, its leader, replied: "Tell your stupid president that he and his Assembly are doomed, and that if within one hour he doesn't deliver to me the twenty-two, I'm going to blast it!"[17] Under this threat of violence, the Convention capitulated and on 2 June 1793, Brissot and the other Girondins were arrested.[18]

Brissot was one of the first Girondins to escape but was also one of the first captured. Passing through his hometown of Chartres on his way to the city of Caen, the center of anti-revolutionary forces in Normandy, he was caught traveling with false papers on 10 June and taken back to Paris.[19] On 3 October, the trial of Brissot and the Girondins began. They were charged with being "agents of the counter-revolution and of the foreign powers, especially Britain."[20] Brissot, who conducted his own defense, attacked point by point the absurdities of the charges against him and his fellow Girondins.

He was unsuccessful and on 30 October, the death sentence was delivered to Brissot and the 28 other Girondins.[21] The next day, the convicted men were taken by tumbrel to the guillotine, singing La Marseillaise as they traveled, and embracing the role of martyred patriots.[22] Brissot was killed using the guillotine at age 39, and his corpse was buried in the Madeleine Cemetery alongside his guillotined associates.

Spying allegations

Robespierre and Marat were among those who accused Brissot of various kinds of counterrevolutionary activity, such as, Orleanism, "federalism", being in the pay of Great Britain, having failed to vote for the immediate death of the former king, and having been a collaborator of General Dumouriez, a traitor of the revolution.[23]

Brissot's activities after the siege of the Bastille have been closely studied. While enthusiasts and apologists consider Brissot to be an idealist, and unblemished, philosophe revolutionary, his detractors have challenged his credibility and moral character. They have repeated contemporary allegations that during the mid-1780s, he was involved in the production and dissemination of pornographic libelles, spied for the police and/or the British, and defrauded his business partner.[24] The accusations were led by Jean-Paul Marat, Camille Desmoulins, Maximilian Robespierre, and above all the notorious scandal-monger, extortioner, and perjurer Charles Théveneau de Morande, whose hatred, Brissot asserted, 'was the torment of my life'.

In the 1980s historian Robert Darnton affirmed some of these accounts.[25] They accused Brissot of being a police spy, saying that he was plotting against the revolution he had once stood behind. Brissot was tried on many occasions to defend himself from these accusations. Darnton argues that Brissot on a personal level did not support the Revolution; for instance, he had gone to a police station to ask if he could be of assistance. When he was turned away, Darnton says, he gave the police information about the revolutionaries. Historian Fredrick Luna has argued that the letters from which Darnton got his information were written fifteen years after the supposed incident. Luna argues that this event could not have occurred as reported; Brissot was documented as having left Paris as soon as he was released from the Bastille, and therefore could not have talked with the police as alleged.[26]

Historian Simon Burrows proposes that Brissot had exhausted his own resources, and thus his survival as writer would depend on collaborating with powerful interests. Burrows says that Brissot's behavior in the late 1780s, (the period when many believed he worked as a spy) suggests a willingness to compromise with authority, including the police, to advance his career and perhaps, ultimately, reform his agenda. Burrows considers Brissot to have been seeking personal advancement.[27]

Legacy

Through his writings Brissot made important contributions to "pre-revolutionary and revolutionary ideology in France".[28] His early works on legislation, his many pamphlets, speeches in the Legislative Assembly and the Convention, demonstrated dedication to the principles of the French Revolution. Brissot's own idea of a fair, democratic society, with universal suffrage, living in moral as well as political freedom, foreshadowed many modern liberationist ideologies.[29]

Brissot was also very interested in science. He was a strong disciple of Sextus Empiricus and applied those theories to modern science at the time in order to make knowledge well known about the enlightenment of Ethos.[30]

The varying actions of Brissot in the 1780s also helped create a key understanding of how the Enlightenment Republic of letters was transformed into a revolutionary Republic of Letters.[31]

Works

- Recherches philosophiques sur le droit de propriété considéré dans la nature, pour servir de premier chapitre à la "Théorie des lois" de M. Linguet, Paris, 1780, 128 p., in-8°.

- Bibliothèque philosophique du Législateur, du Politique et du Jurisconsulte, Berlin et Paris, 1782-1786, 10 vol. in-8°.

- Bibliotheque philosophique du législateur, du politique, du jurisconsulte (in French). 1. Berlin : Desauges ; Lyon : Grabit & Rosset. 1782.

- Bibliotheque philosophique du législateur, du politique, du jurisconsulte (in French). 3. Berlin : Desauges ; Lyon : Grabit & Rosset. 1783.

- Bibliotheque philosophique du législateur, du politique, du jurisconsulte (in French). 4. Berlin : Desauges ; Lyon : Grabit & Rosset. 1782.

- Bibliotheque philosophique du législateur, du politique, du jurisconsulte (in French). 5. Berlin : Desauges ; Lyon : Grabit & Rosset. 1782.

- Bibliotheque philosophique du législateur, du politique, du jurisconsulte (in French). 6. Berlin : Desauges ; Lyon : Grabit & Rosset. 1782.

- Bibliotheque philosophique du législateur, du politique, du jurisconsulte (in French). 7. Berlin : Desauges ; Lyon : Grabit & Rosset. 1782.

- Bibliotheque philosophique du législateur, du politique, du jurisconsulte (in French). 8. Berlin : Desauges ; Lyon : Grabit & Rosset. 1782.

- Bibliotheque philosophique du législateur, du politique, du jurisconsulte (in French). 9. Berlin : Desauges ; Lyon : Grabit & Rosset. 1782.

- Bibliotheque philosophique du législateur, du politique, du jurisconsulte (in French). 10. Berlin : Desauges ; Lyon : Grabit & Rosset. 1785.

- Moyens d’adoucir la rigueur des lois pénales en France sans nuire à la sécurité publique, Discours couronné par l’Académie de Châlons-sur-Marne en 1780, Châlons, 1781, in-8°.

- Théorie des lois criminelles, Paris, 1781, 2 vol. in-8°.

- De la Vérité des Méditations sur les moyens de parvenir à la vérité dans toutes les connaissances humaines, Neufchâtel et Paris, 1782, in-8°.

- Discours sur la nécessité de maintenir le décret rendu le 13 mai 1791, en faveur des hommes de couleur libres, prononcé le 12 septembre 1791, à la séance de la Société des Amis de la Constitution, séante aux jacobins.

- Discours sur la nécessité politique de révoquer le décret du 24 septembre 1791, pour mettre fin aux troubles de Saint Domingue; prononcé à l'Assemblée nationale, le 2 mars 1792. Par J.P. Brissot, député du département de Paris, Paris : De l'Imprimerie du patriote françois, 1792.

- Correspondance universelle sur ce qui intéresse le bonheur de l’homme et de la société, Londres et Neufchâtel, 1783, 2 vol. in-8°.

- Journal du Lycée de Londres, ou Tableau des sciences et des arts en Angleterre, Londres et Paris, 1784.

- Tableau de la situation actuelle des Anglais dans les Indes orientales, et Tableau de l’Inde en général, ibid., 1784, in-8°.

- L’Autorité législative de Rome anéantie, Paris, 1785, in-8°, réimprimé sous le titre : Rome jugée, l’autorité du pape anéantie, pour servir de réponse aux bulles passées, nouvelles et futures du pape, ibid., 1731, m-g.

- Examen critique des voyages dans l'Amérique septentrionale, de M. le marquis de Chatellux, ou Lettre à M. le marquis de Chatellux, dans laquelle on réfute principalement ses opinions sur les quakers, sur les nègres, sur le peuple et sur l'homme, par J.-P. Brissot de Warville, Londres, 1786, in-8°.

- Discours sur la Rareté du numéraire, et sur les moyens d’y remédier, 1790, in-8°.

- Mémoire sur les Noirs de l’Amérique septentrionale, 1790, in-8°.

- Voyage aux États-Unis, 1791.

His Mémoires and his Testament politique (4 vol.) were published in 1829-1832 by his sons with François Mongin de Montrol:

- Mémoires de Brissot... sur ses contemporains, et la révolution française ; publ. par son fils ; notes et éclaircissements hist. par M.F. de Montrol, 1830-1832; Vol. I (1830); Vol. II (1830); Vol. III (1832); Vol. IV (1832).

See also

Notes

- Frederick A. de Luna, " The Dean Street Style of Revolution: J.-P. Brissot, Jeune Philosophe ", pp. 162 in: The French Historical Studies, Volume 17, No. 1 (Spring 2001)

- "Jacques-Pierre Brissot | French revolutionary leader". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- http://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/columency/brissot_de_warville_jacques_pierre/0?searchId=1d4ffaa6-01d2-11e7-8483-0aea1e3b2a47&result=0%5B%5D

- Brissot de Warville (1781). Théorie des lois criminelles (in French). 1.

- Loft, Lenore (2009). "Brissot, Jacques Pierre (1754–1793)". The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest : 1500 to the present. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 1–3. doi:10.1002/9781405198073.wbierp0247. ISBN 9781405184649.

- Léonore Loft, "The Transylvanian Peasant Uprising of 1784, Brissot and the Right to Revolt: A Research Note", pp. 209-218 in: French Historical Studies, Vol. 17, No. 1 (Spring, 1991)

- Berges, Sandrine (2015). "Sophie de Grouchy on the Cost of Domination in the Letters on Sympathy and Two Anonymous Articles in Le Républicain" (PDF). Monist. 98: 102–112. doi:10.1093/monist/onu011. hdl:11693/12519.

- "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter B" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- David Andress, 1789: The Threshold of the Modern Age, 87.

- Christopher Hibbert, The Days of the French Revolution, 137.

- http://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/columency/girondists/0?searchId=feb02140-1287-11e7-87c6-0e58d2201a4d&result=2 Archived 15 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Archived 15 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Jeremy D. Popkin, " The Defeat of the Liberal Revolution ", pp. 73 in: A Short History of the French Revolution, Fifth Edition (2010)

- Thomas Lalevée, "National Pride and Republican grandezza: Brissot’s New Language for International Politics in the French Revolution", French History and Civilisation (Vol. 6), 2015, pp. 66-82.

- David Andress, The Terror, p. 175.

- David Andress, The Terror, p. 176.

- David Andress, The Terror,p. 382.

- David Andress, The Terror, p. 180.

- David Andress, The Terror, p. 228.

- David Andress, The Terror, p. 229.

- David Andress, The Terror, p. 230.

- Frederick A. de Luna, "The Dean Street Style of Revolution: J.-P. Brissot, Jeune Philosophe", p. 178 in: The French Historical Studies, Volume 17, No. 1 (Spring 2001)

- Simon Burrows, "The Innocence of Jacques-Pierre Brissot," pp. 843-871.

- Robert Darnton, The Literary Underground of the Old Regime, Harvard University Press, 1982, pp. 49-68.

- Frederick A. Luna, "Interpreting Brissot", The Dean Street Style of Revolution, pp. 159–190.

- Burrows, "The Innocence of Jacques-Pierre Brissot" pp. 884–885

- Loft, p. 209.

- Leonore Loft, Passion, Politics, and Philosophie : Rediscovering J.-P. Brissot'', (2001)

- Charles, Sébastien (1 January 2013). "From Universal Pyrrhonism to Revolutionary Scepticism: Jacques-Pierre Brissot de Warville". In Charles, Sébastien; Smith, Plínio J. (eds.). Scepticism in the Eighteenth Century: Enlightenment, Lumières, Aufklärung. International Archives of the History of Ideas Archives internationales d'histoire des idées. Springer Netherlands. pp. 231–244. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-4810-1_16. ISBN 9789400748095.

- Denna Goodman, "Conclusion", pp. 73 in: The Republic of Letters: A Cultural History of the French enlightenment, (1994)

Further reading

- Burrows, Simon. "The Innocence of Jacques-Pierre Brissot." Historical Journal (2003): 843-871. online

- Darnton, Robert. "The Brissot Dossier." French Historical Studies 17.1 (1991): 191-205. online

- De Luna, Frederick A. "The Dean Street style of revolution: J.-P. Brissot, jeune philosophe." French Historical Studies 17.1 (1991): 159-190.

- Durand, Echeverria, and Mara Vamos (New Travels in the United States of America. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1964) ix-xxvii

- D'huart, Suzanne (1986). Brissot : la Gironde au pouvoir (in French). Paris: R. Laffont. ISBN 978-2-221-04686-9.

- Ellery, Eloise. Brissot de Warville: A study in the history of the French Revolution (1915) online.

- Marisa Linton, Choosing Terror: Virtue, Friendship and Authenticity in the French Revolution (Oxford University Press, 2013).

- Marisa Linton, "The First Step on the Road to Waterloo", History Today, vol 65, issue 6, June 2015..

- Marisa Linton, 'Friends, Enemies and the Role of the Individual,' in Peter McPhee (ed.), Companion to the History of the French Revolution (Wiley-Blackwell, 2013): 263-77.

- Lalevée, Thomas. "National Pride and Republican grandezza: Brissot’s New Language for International Politics in the French Revolution", French History and Civilisation (Vol. 6), 2015, pp. 66–82.

- Loft, Leonore. "J.-P. Brissot and the evolution of pamphlet literature in the early 1780s." History of European ideas' 17.2-3 (1993): 265-287.

- Loft, Leonore. Passion, politics, and philosophie: Rediscovering J.-P. Brissot (Greenwood, 2002).

- Oliver, Bette W. Jacques Pierre Brissot in America and France, 1788–1793: In Search of Better Worlds (Rowman & Littlefield, 2016).

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Jacques Pierre Brissot |

- Works by or about Jacques Pierre Brissot at Internet Archive

- Works by Jacques Pierre Brissot at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Full text online versions of pamphlets written by Jacques Pierre Brissot from the Ball State University Digital Media Repository