Treaty of Lunéville

The Treaty of Lunéville was signed in the Treaty House of Lunéville on 9 February 1801. The signatory parties were the French Republic and Holy Roman Emperor Francis II. The latter was negotiating both on his own behalf as ruler of the hereditary domains of the Habsburg Monarchy and on behalf of other rulers who controlled territories in the Holy Roman Empire. The signatories were Joseph Bonaparte and Count Ludwig von Cobenzl, the Austrian foreign minister.

Long name:

| |

|---|---|

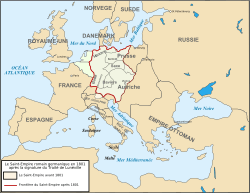

Europe after Lunéville | |

| Type | Peace treaty |

| Context | War of the Second Coalition |

| Signed | 9 February 1801 |

| Location | Lunéville, France |

| Signatories | |

The Austrian army had been defeated by Napoleon Bonaparte at the Battle of Marengo on 14 June 1800 and then by Jean Victor Moreau at the Battle of Hohenlinden on 3 December. Forced to sue for peace, the Austrians signed the treaty of Lunéville, which largely confirmed the treaty of Campo Formio (October 1797), which itself had confirmed the treaty of Leoben (April 1797). The United Kingdom was the sole nation still at war with France for another year. The treaty, along with the Anglo-French Treaty of Amiens of 1802, marked the end of the Second Coalition against the French First Republic.

Terms

The Treaty of Lunéville declared that "there shall be, henceforth and forever, peace, amity, and good understanding" among the parties. The treaty required Austria to enforce the conditions of the earlier Treaty of Campo Formio (concluded on 17 October 1797). Certain Austrian holdings within the borders of the Holy Roman Empire were relinquished, and French control was extended to the left bank of the Rhine, "in complete sovereignty" but France renounced any claim to territories east of the Rhine. Contested boundaries in Italy were set.

The Grand Duchy of Tuscany was awarded to the French, but the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Ferdinand III, was promised territorial compensations in Germany. In a secret article, the compensations were tentatively set to be the Archbishopric of Salzburg and Berchtesgaden.[1] The two parties agreed to respect the independence of the Batavian, Cisalpine, Helvetic and Ligurian Republics. On the other hand, Austria's possession of Venetia and Dalmatian coast was confirmed.

Consequences for the Holy Roman Empire

The Treaty of Lunéville in Article 6 reaffirmed the cession of all territory of the Empire to France on the left bank of the river Rhine. Article 7 stipulated that the princes, whose territories were partly or wholly ceded, were to be compensated with lands from within the new borders of the Empire. The territories lost included the Austrian Netherlands, Savoy, and imperial Italy. The task of compensation was left to an Imperial Deportation (German: Reichsdeputation). France and Russia greatly influenced the negotiations, with France urging for larger new territories to be formed, which it hoped would later ally with them, while Russia favoured "a more traditional balance".[2] Eventually, the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss (Imperial Recess), the final document which reorganised the Empire, was signed on 25 February 1803. The Recess did far more than simply satisfy the need to compensate the princes, but fundamentally restructured the Empire by secularising all ecclesiastical states except for the Electorate of Mainz. Almost all free imperial cities lost their sovereignty. The Reichsdeputationshauptschluss was the last major law in the history of the Holy Roman Empire before its dissolution in 1806.[3][4]

End of peace

The Austrians resumed war against France in 1805.

See also

References

- see the text of the treaty

- Wilson 2017, p. 649.

- Stollberg-Rilinger 2013, p. 113.

- Gotthard 2013, pp. 157–159.

Bibliography

- Gotthard, Axel (2013). Das Alte Reich 1495–1806 (in German). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. ISBN 978-3-534-25929-8.

- Stollberg-Rilinger, Barbara (2013). Das Heilige Römische Reich Deutscher Nation – Vom Ende des Mittelalters bis 1806 (in German). Munich: C.H. Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-72247-9.

- Wilson, Peter H. (2017). The Holy Roman Empire – A Thousand Years of Europe's History. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-141-04747-8.