Joseph Bonaparte

Joseph-Napoléon Bonaparte, Comte de Survilliers, (born Giuseppe di Buonaparte [Italian: [dʒuˈzɛppe di ˌbwɔnaˈparte]]; Spanish: José Napoleón Bonaparte; 7 January 1768 – 28 July 1844) was a French lawyer and diplomat, the older brother of Napoleon Bonaparte, who made him King of Naples and Sicily (1806–1808, as Giuseppe I), and later King of Spain (1808–1813, as José I). After the fall of Napoleon, Joseph styled himself Comte de Survilliers.

| Joseph Bonaparte | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portrait as King of Spain by François Gérard, 1808 | |||||

| King of Spain and the Indies | |||||

| Reign | 6 June 1808 – 11 December 1813 | ||||

| Predecessor | Ferdinand VII | ||||

| Successor | Ferdinand VII | ||||

| King of Naples and Sicily | |||||

| Reign | 30 March 1806 – 6 June 1808 | ||||

| Predecessor | Ferdinand IV | ||||

| Successor | Joachim I | ||||

| Born | 7 January 1768 Corte, Corsica, Republic of Genoa | ||||

| Died | 28 July 1844 (aged 76) Florence, Tuscany | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue | Zénaïde Laetitia Julie Bonaparte Charlotte Napoléone Bonaparte | ||||

| |||||

| House | Bonaparte | ||||

| Father | Carlo Buonaparte | ||||

| Mother | Letizia Ramolino | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||

Early years and personal life

Joseph was born in 1768 to Carlo Buonaparte and Maria Letizia Ramolino at Corte, the capital of the Corsican Republic. In the year of his birth, Corsica was invaded by France and conquered the following year. His father was originally a follower of the Corsican Patriot leader, Pasquale Paoli, but later became a supporter of French rule.

As a lawyer, politician and diplomat, Joseph served in the Cinq-Cents and was the French ambassador to Rome. On 30 September 1800, as Minister Plenipotentiary, he signed a treaty of friendship and commerce between France and the United States at Morfontaine, alongside Charles Pierre Claret de Fleurieu, and Pierre Louis Roederer.

In 1795 Joseph was a member of the Council of Ancients, where he used his position to help his brother overthrow the Directory four years later.

The Château de Villandry had been seized by the French Revolutionary government and, in the early 19th century, Joseph's brother, the Emperor Napoleon, acquired the château for him.

King of Naples

Upon the outbreak of war between France and Austria in 1805, Ferdinand IV of Naples had agreed a treaty of neutrality with Napoleon but, a few days later, declared his support for Austria and permitted a large Anglo-Russian force to land in his kingdom. Napoleon, however, was soon victorious and, with the War of the Third Coalition having been shattered on 5 December at the Battle of Austerlitz, Ferdinand found himself exposed to French wrath.

.jpg)

On 27 December 1805, Napoleon issued a proclamation from the Schönbrunn declaring Ferdinand to have forfeited his kingdom and that a French invasion would soon follow ensuring 'that the finest of countries is relieved from the yoke of the most faithless of men.'[1] On 31 December Napoleon commanded Joseph to leave Paris and move to Rome, where he would be assigned at the head of the army sent to dispossess Ferdinand of his throne. Although Joseph was the nominal commander-in-chief of the expedition, Marshal Masséna was in effective command of operations, with General St. Cyr second. However St. Cyr, who had previously held the senior command of French troops in the region, soon resigned in protest at being made subordinate to Masséna and left for Paris. An outraged Napoleon ordered St. Cyr to return to his post at once.[2]

On 8 February 1806 the French invasion force of forty-thousand men crossed into Naples. The centre and right of the army under Masséna and General Reynier advanced south from Rome while Giuseppe Lechi led a force down the Adriatic coast from Ancona. On his brother's recommendation, Joseph attached himself to Reynier.[3] The French advance faced little resistance. Even before any French troops had crossed the border, the Anglo-Russian forces had beaten a prudent retreat, the British withdrawing to Sicily, the Russians to Corfu. Thus abandoned by his allies, King Ferdinand had also already set sail for Palermo on 23 January. Queen Maria-Carolina lingered a little longer in the capital but, on 11 February, also fled to join her husband.

The first obstacle the French encountered was the fortress of Gaeta, its governor, Prince Louis of Hesse-Philippsthal, refusing to surrender his charge. This did not however result in any meaningful delay of the invaders, Masséna simply detaching a small force to besiege the garrison before continuing south, where Capua opened its gates after only token resistance.[4] On 14 February Masséna took possession of Naples and, the following day, Joseph staged a triumphant entrance into the city.[5] Reynier was then quickly dispatched to seize control of the Strait of Messina and on 9 March inflicted a crushing defeat on the Neapolitan Royal Army at the Battle of Campo Tenese, effectively destroying it as a fighting force and securing the entire mainland for the French.

.jpg)

On 30 March 1806 Napoleon issued a decree installing Joseph as King of Naples and Sicily, the decree reading as follows:

"Napoleon, by the Grace of God and the constitutions. Emperor of the French and King of Italy, to all those to whom these presents come, greetings. The interests of our people, the honour of our Crown, and the tranquillity of the Continent of Europe requiring that we should assure, in a stable and definite manner, the lot of the people of Naples and of Sicily, who have fallen into our power by the right of conquest, and who constitute a part of the Grand Empire, we declare that we recognise, as King of Naples and of Sicily, our well-beloved brother, Joseph Napoleon, Grand Elector of France. This Crown will be hereditary, by order of primogeniture, in his descendants male, legitimate, and natural, etc."[6]

Joseph's arrival in Naples was warmly greeted with cheers and he was eager to be a monarch well liked by his subjects. Seeking to win the favour of the local elites, he maintained in their posts the vast majority of those who had held office and position under the Bourbons and was anxious to not in any way appear a foreign oppressor. With a provisional government set up in the capital, Joseph then immediately set off, accompanied by General Lamarque, on a tour of his new realm. The principal object of the tour was to assess the feasibility of an immediate invasion of Sicily and the expulsion of Ferdinand and Maria-Carolina from their refuge in Palermo. But, upon reviewing the situation at the Strait of Messina, Joseph was forced to admit the impossibility of such an enterprise, the Bourbons having carried off all boats and transports from along the coast and concentrated their remaining forces, alongside the British, on the opposite side.[7] Unable to possess himself of Sicily, Joseph was nevertheless master of the mainland and he continued his progress through Calabria and on to Lucania and Apulia, visiting the main villages and meeting the local notables, clergy and people, allowing his people to grow accustomed to their new king and enabling himself to form first-hand a picture of the condition of his kingdom.[8]

Upon returning to Naples, Joseph received a deputation from the French Senate congratulating him upon his accession. The King then set about forming a ministry staffed by many competent and talented men with whom he was determined to pursue a reforming agenda and confer upon Naples all the benefits of the French Revolution, without its excesses. Saliceti was appointed Minister of Police, Roederer Minister of Finance, Miot Minister of the Interior and General Dumas Minister of War. Marshal Jourdan was also confirmed as Governor of Naples, an appointment made by Napoleon, and served as Joseph's foremost military adviser.

Joseph then embarked on an ambitious programme of reform and regeneration aimed at raising Naples to the level of a modern state in the mould of Napoleonic France. Monastic orders were suppressed, their property nationalised and their funds confiscated to steady the royal finances.[9] Feudal privileges and taxes were abolished, however the nobility was compensated by an indemnity in the form of a certificate which could be exchanged in return for lands nationalised from the Church.[10] Moreover, provincial intendants were instructed to engage those dispossessed former monks who had the inclination in the work of public education, and to ensure that elderly monks no longer able to support themselves were moved into communal establishments founded for their care.[11] A college for the education of young girls was also established in each province and a central college at Aversa was founded to which the daughters of public functionaries, and the ablest from the provincial schools, were admitted under the personal patronage of Queen Julie.[12]

The practice of forcibly recruiting prisoners into the army was also abolished and, to counter the perennial plague of robbers and brigands who infested the mountains and preyed upon travellers, military commissions were established with the power to judge and execute, without appeal, all those brigands arrested with arms in their possession.[13] Public works programmes were also instituted to give employment to the poor and improvement to the kingdom, with practicable highways being built all the way to Reggio and the project of a Calabrian road, which under the Bourbons had existed for decades only as the pretext for a tax levied each year ostensibly for its construction, was completed by Joseph within the year.[14] In the second year of his reign, Joseph also had installed the first system of public street-lighting in Naples itself, modelled on that then operating in Paris.[10]

Although the kingdom was not at that time furnished with a constitution, and thus Joseph's will as monarch reigned supreme, there is yet no instance of him ever adopting a measure of policy without prior discussion of the matter in the Council of State and the passing of a majority vote in favour his course of action by the counsellors.[15] Joseph thus presided over Naples in the best traditions of Enlightened absolutism, doubling the revenue of the crown from seven to fourteen million ducats in his brief two-year reign while all the time seeking to lighten the burdens of his people rather than increase them.[16]

Joseph ruled Naples for two years before being replaced by his sister's husband, Joachim Murat. Joseph was then made King of Spain in August 1808, soon after the French invasion.

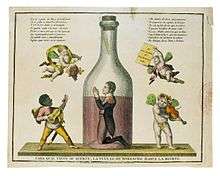

King of Spain

Joseph somewhat reluctantly left Naples, where he was popular, and arrived in Spain where he was extremely unpopular. Joseph came under heavy fire from his opponents in Spain, who tried to smear his reputation by calling him Pepe Botella (Joe Bottle) for his alleged heavy drinking, an accusation echoed by later Spanish historiography, despite the fact that Joseph was abstemious. His arrival sparked a Spanish revolt against French rule, and the beginning of the Peninsular War. Thompson says the Spanish revolt was, "a reaction against new institutions and ideas, a movement for loyalty to the old order: to the hereditary crown of the Most Catholic kings, which Napoleon, an excommunicated enemy of the Pope, had put on the head of a Frenchman; to the Catholic Church persecuted by republicans who had desecrated churches, murdered priests, and enforced a "loi des cultes" (law of religion); and to local and provincial rights and privileges threatened by an efficiently centralized government.[17]

Joseph temporarily retreated with much of the French Army to northern Spain. Feeling himself in an ignominious position, Joseph then proposed his own abdication from the Spanish throne, hoping that Napoleon would sanction his return to the Neapolitan Throne he had formerly occupied. Napoleon dismissed Joseph's misgivings out of hand, and to back up the raw and ill-trained levies he had initially allocated to Spain, the Emperor sent heavy French reinforcements to assist Joseph in maintaining his position as King of Spain. Despite the easy recapture of Madrid, and nominal control by Joseph's government over many cities and provinces, Joseph's reign over Spain was always tenuous at best, and constantly resisted by pro-Bourbon guerrillas. Joseph and his supporters never established complete control over the country.

King Joseph's Spanish supporters were called josefinos or afrancesados (frenchified). During his reign, he ended the Spanish Inquisition, partly because Napoleon was at odds with Pope Pius VII at the time. Despite such efforts to win popularity, Joseph's foreign birth and support, plus his membership of a Masonic lodge,[18] virtually guaranteed he would never be accepted as legitimate by the bulk of the Spanish people. During Joseph's rule of Spain, Venezuela declared independence from Spain. The king had virtually no influence over the course of the ongoing Peninsular War: Joseph's nominal command of French forces in Spain was mostly illusory, as the French commanders theoretically subordinate to King Joseph insisted on checking with Napoleon before carrying out Joseph's instructions.

King Joseph abdicated and returned to France after the main French forces were defeated by a British-led coalition at the Battle of Vitoria in 1813. During the closing campaign of the War of the Sixth Coalition Napoleon left his brother to govern Paris with the title Lieutenant General of the Empire. As a result, he was again in nominal command of the French Army at the Battle of Paris.

He was seen by Bonapartists as the rightful Emperor of the French after the death of Napoleon's own son Napoleon II in 1832, although he did little to advance his claim.

United States

Joseph lived primarily in the United States (where he sold the jewels he had taken from Spain) in the period 1817–1832,[19] initially in New York City and Philadelphia, where his house became the centre of activity for French expatriates, but later moved to an estate, formerly owned by Stephen Sayre, called Point Breeze in Bordentown, New Jersey. Joseph's home was located near the confluence of Crosswicks Creek and the Delaware River. He considerably expanded Sayre's home and created extensive gardens in the picturesque style. When his first home was destroyed by fire in January 1820 he converted his stables into a second grand house. At Point Breeze, Joseph entertained many of the leading intellectuals and politicians of his day.

In the summer of 1825, the Quaker scientist Reuben Haines III wrote a detailed description of Bonaparte's estate at Point Breeze, in a letter to his cousin:

"I partook of royal fare on solid silver and attended by six waiters who supplied me with 9 courses of the most delicious viands, many of which I could not possibly tell what they were composed of; spending the intermediate time in Charles' private rooms looking over the Herbarium and Portfolios of the Princess, or riding with her and the Prince drawn by two Elegant Horses along the ever varying roads of the park amidst splendid Rhododendrons on the margin of the artificial lake on whose smooth surface gently glided the majestic European swans. Stopping to visit the Aviary enlivened by the most beautiful English pheasants, passing by alcoves ornamented with statues and busts of Parian marble, our course enlivened by the footsteps of the tame deer and the flight of the Woodcock, and when alighting stopping to admire the graceful form of two splendid Etruscan vases of Porphyry 3 ft. high & 2 in diameter presented by the Queen of Sweden [Joseph's sister-in-law Desiree Clary Bernadotte] or ranging [?] through the different appartments of the mansion through a suite of rooms 15 ft. in [height] decorated with the finest productions of the pencils of Coregeo [sic]! Titian! Rubens! Vandyke! Vernet! Tenniers [sic] and Paul Potter and a library of the most splended books I ever beheld."[20][21]

According to legend, during this period he had an encounter with the mythical Jersey Devil.

Reputedly some Mexican revolutionaries offered to crown him Emperor of Mexico in 1820, but he declined.[19]

Joseph Bonaparte returned to Europe, where he died in Florence, Italy, and was buried in the Les Invalides building complex in Paris.[22]

Family

He married Marie Julie Clary daughter of François Clary on 1 August 1794 in Cuges-les-Pins, France. They had three daughters:

- Julie Joséphine Bonaparte (29 February 1796 - 6 June 1797).

- Zénaïde Laetitia Julie Bonaparte (8 July 1801 – 1854); married, in 1822 to Charles Lucien Bonaparte.

- Charlotte Napoléone Bonaparte (31 October 1802 – 2 March 1839); married, in 1826 to Napoleon Louis Bonaparte.

He claimed the two surviving daughters as his heirs. He also sired two children with Maria Giulia Colonna, the Countess of Atri:

- Giulio (1806–1838)

- Teresa (1808–died in infancy).

Joseph had two American daughters born at Point Breeze, his estate in Bordentown, New Jersey, by his mistress, Annette Savage ("Madame de la Folie"):

- Pauline Anne; died young.

- Catherine Charlotte (1822–1890); married Col. Zebulon Howell Benton of Jefferson County, New York, and had issue:[23] Louis Joseph Benton (1848-1940) and son Frederick Joseph Benton (1901-1967)[24]

Freemasonry

Joseph Bonaparte was admitted to Marseille's lodge la Parfaite Sincérité in 1793.[25][26][27] He was asked by his brother Napoleon to monitor freemasonry as Grand Master of the Grand Orient of France (1804–1815).[28][29][30][31] With Cambacérès he managed the post-revolution rebirth of the Order in France.[28][32][33][34]

Gallery

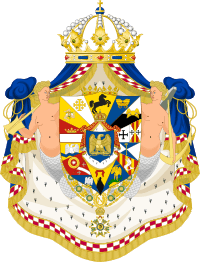

Coat of arms as King of Naples

Coat of arms as King of Naples Coat of arms as King of Spain

Coat of arms as King of Spain Royal monogram as King of Spain

Royal monogram as King of Spain Spanish gold coin from 1811

Spanish gold coin from 1811

Legacy

- Joseph Bonaparte Gulf in the Northern Territory of Australia is named after him.

- Lake Bonaparte, located in the town of Diana, New York, United States, is also named after him.

- A main character in the play Golden Boy by Clifford Odets is named Joe Bonaparte after him.

Fictional portrayals

The romantic web between Joseph Bonaparte, Napoleon, Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte, Julie Clary and Désirée Clary was the subject of the 1951 novel Désirée, by Annemarie Selinko.

The novel was filmed as Désirée in 1954, with Marlon Brando as Napoleon, Jean Simmons as Désirée, and Cameron Mitchell as Joseph Bonaparte.

In his 1955 historical novel The Tontine, Thomas B. Costain describes a visit by one of his protagonists to Joseph Bonaparte's estate at Point Breeze in Bordentown, New Jersey, and his involvement in some minor Napoleonic intrigue.

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Joseph Bonaparte | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- The Confidential Correspondence of Napoleon Bonaparte with his Brother Joseph, Vol. 1, 80.

- The Confidential Correspondence of Napoleon Bonaparte with his Brother Joseph, Vol. 1, 82.

- The Confidential Correspondence of Napoleon Bonaparte with his Brother Joseph, Vol. 1, 81.

- J. S. C. Abbott, A History of Joseph, King of Naples, 104.

- J. S. C. Abbott, A History of Joseph, King of Naples, 105.

- J. S. C. Abbott, A History of Joseph, King of Naples, 105-6.

- Biographical Sketch of Joseph Napoleon Bonaparte, Count de Survilliers, 15.

- Biographical Sketch of Joseph Napoleon Bonaparte, Count de Survilliers, 16.

- Biographical Sketch of Joseph Napoleon Bonaparte, Count de Survilliers, 22.

- Biographical Sketch of Joseph Napoleon Bonaparte, Count de Survilliers, 29.

- Biographical Sketch of Joseph Napoleon Bonaparte, Count de Survilliers, 23.

- Biographical Sketch of Joseph Napoleon Bonaparte, Count de Survilliers, 24.

- Biographical Sketch of Joseph Napoleon Bonaparte, Count de Survilliers, 24; J. S. C. Abbott, A History of Joseph, King of Naples, 113.

- Biographical Sketch of Joseph Napoleon Bonaparte, Count de Survilliers, 25.

- Biographical Sketch of Joseph Napoleon Bonaparte, Count de Survilliers, 34-5.

- Biographical Sketch of Joseph Napoleon Bonaparte, Count de Survilliers, 35.

- J. M. Thompson, Napoleon Bonaparte: His Rise and Fall (1951) 244-45

- Ross, Michael The Reluctant King, 1977, pp. 34–35

- "Joseph Bonaparte at Point Breeze". Flat Rock. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- Stroud, Patricia Tyson (2000). The Emporer of Nature: Charles-Lucien Bonaparte and his World. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0812235463.

- Wyck Association Collection (Mss.Ms.Coll.52). American Philosophical Society Library. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. https://search.amphilsoc.org/collections/view?docId=ead/Mss.Ms.Coll.52-ead.xml;query=Wyck;brand=default#top

- Kwoh, Leslie (10 June 2007). "Yes, a Bonaparte feasted here". Star Ledger. Archived from the original on 8 December 2008. Retrieved 19 February 2008.

- The Growth of a Century: as Illustrated in the History of Jefferson County

- 1880 and 1910 US CENSUS Pennsylvania population via Ancestry.com

- La franc-maçonnerie Jean Massicot (Desnoël ed.)

- Les Francs-maçons et leur religion Jacques Duchenne (Publibook ed.)

- Revue d'histoire de Bayonne, du pays basque et du Bas-Adour, Numéro 159, page 176

- Franc-maçonnerie et politique au siècle des lumières: Europe-Amérique page 55 – article Le binôme franc-maçonnerie-Révolution – José Ferrer Benimeli (Presses Univ de Bordeaux ed., 2006)

- Histoire de la franc-maçonnerie en France Jean André Faucher and Achille Ricker (Nouvelles éditions latines ed., 1967)

- Histoire du Grand Orient de France page 338, Achille Godefroy Jouaust, (Brissard et Teissier ed. 1865)

- Chronique de la Franc-maçonnerie en Corse: 1772-1920 page 66 - Charles Santoni ( A. Piazzola ed., 1999)

- Les francs-maçons: Des inconditionnels de l'espoir page 22 François Deschatres (L’Harmattan ed. 2012)

- Histoire de la franc-maçonnerie en France – page 231 Jean André Faucher and Achille Ricker

- Essai sur l'origine et l'histoire de la franc-maçonnerie en Guadeloupe - Guy Monduc (G. Monduc ed., 1985)

Further reading

- Schom, Alan (1997). Napoleon Bonaparte: A Life. New York: Harper Collins. ISBN 9780060929589.

- Stroud, Patricia Tyson (2005). The Man who had been King: The American Exile of Napoleon's Brother Joseph. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812290424. biography: book received the New Jersey Council for the Humanities first place book award in 2006.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Joseph Bonaparte. |

- Joseph Bonaparte at Point Breeze

- Joseph Bonaparte and the Jersey Devil

- Antiguo Régimen: José I Bonaparte (in Spanish)

- . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

- Spencer Napoleonica Collection at Newberry Library

Joseph Bonaparte Born: 7 January 1768 Died: 28 July 1844 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Ferdinand IV |

King of Naples 1806 – 1808 |

Succeeded by Joachim I |

| Preceded by Ferdinand VII |

King of Spain 1808 – 1813 |

Succeeded by Ferdinand VII |

| Titles in pretence | ||

| Preceded by Napoléon II |

— TITULAR — Emperor of the French King of Italy 22 July 1832 – 28 July 1844 |

Succeeded by Louis I |

2.svg.png)

.svg.png)