Jacques-Louis David

Jacques-Louis David (French: [ʒaklwi david]; 30 August 1748 – 29 December 1825) was a French painter in the Neoclassical style, considered to be the preeminent painter of the era. In the 1780s his cerebral brand of history painting marked a change in taste away from Rococo frivolity toward classical austerity and severity and heightened feeling,[1] harmonizing with the moral climate of the final years of the Ancien Régime.

Jacques-Louis David | |

|---|---|

Self portrait, 1794, Musée du Louvre | |

| 33rd President of the National Convention | |

| In office 5 January 1794 – 20 January 1794 | |

| Preceded by | Georges Auguste Couthon |

| Succeeded by | Marc Guillaume Alexis Vadier |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 30 August 1748 Paris, Kingdom of France |

| Died | 29 December 1825 (aged 77) Brussels, United Netherlands |

| Nationality | French |

| Alma mater | Collège des Quatre-Nations, University of Paris |

| Awards | Prix de Rome Commander of the Legion of Honour |

David later became an active supporter of the French Revolution and friend of Maximilien Robespierre (1758–1794), and was effectively a dictator of the arts under the French Republic. Imprisoned after Robespierre's fall from power, he aligned himself with yet another political regime upon his release: that of Napoleon, The First Consul of France. At this time he developed his Empire style, notable for its use of warm Venetian colours. After Napoleon's fall from Imperial power and the Bourbon revival, David exiled himself to Brussels, then in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, where he remained until his death. David had many pupils, making him the strongest influence in French art of the early 19th century, especially academic Salon painting.

Early life

Jacques-Louis David was born into a prosperous French family in Paris on 30 August 1748. When he was about nine his father was killed in a duel and his mother left him with his well-off architect uncles. They saw to it that he received an excellent education at the Collège des Quatre-Nations, University of Paris, but he was never a good student—he had a facial tumor that impeded his speech, and he was always preoccupied with drawing. He covered his notebooks with drawings, and he once said, "I was always hiding behind the instructor's chair, drawing for the duration of the class". Soon, he desired to be a painter, but his uncles and mother wanted him to be an architect. He overcame the opposition, and went to learn from François Boucher (1703–1770), the leading painter of the time, who was also a distant relative. Boucher was a Rococo painter, but tastes were changing, and the fashion for Rococo was giving way to a more classical style. Boucher decided that instead of taking over David's tutelage, he would send David to his friend, Joseph-Marie Vien (1716–1809), a painter who embraced the classical reaction to Rococo. There, David attended the Royal Academy, based in what is now the Louvre.

Each year the Academy awarded an outstanding student the prestigious Prix de Rome, which funded a 3- to 5-year stay in the Eternal City. Since artists were now revisiting classical styles, the trip to Rome provided its winners the opportunity to study the remains of classical antiquity and the works of the Italian Renaissance masters at first hand. Each pensionnaire was lodged in the French Academy's Roman outpost, which from the years 1737 to 1793 was the Palazzo Mancini in the Via del Corso. David competed for, and failed to win, the prize for three consecutive years (with Minerva Fighting Mars, Diana and Apollo Killing Niobe's Children and The Death of Seneca). Each failure contributed to his lifelong grudge against the institution. After his second loss in 1772, David went on a hunger strike, which lasted two and a half days before the faculty encouraged him to continue painting. Confident he now had the support and backing needed to win the prize, he resumed his studies with great zeal—only to fail to win the Prix de Rome again the following year. Finally, in 1774, David was awarded the Prix de Rome on the strength of his painting of Erasistratus Discovering the Cause of Antiochus' Disease, a subject set by the judges. In October 1775 he made the journey to Italy with his mentor, Joseph-Marie Vien, who had just been appointed director of the French Academy at Rome.[2]

While in Italy, David mostly studied the works of 17th-century masters such as Poussin, Caravaggio, and the Carracci.[2] Although he declared, "the Antique will not seduce me, it lacks animation, it does not move",[2] David filled twelve sketchbooks with drawings that he and his studio used as model books for the rest of his life. He was introduced to the painter Raphael Mengs (1728–1779), who opposed the Rococo tendency to sweeten and trivialize ancient subjects, advocating instead the rigorous study of classical sources and close adherence to ancient models. Mengs' principled, historicizing approach to the representation of classical subjects profoundly influenced David's pre-revolutionary painting, such as The Vestal Virgin, probably from the 1780s. Mengs also introduced David to the theoretical writings on ancient sculpture by Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768), the German scholar held to be the founder of modern art history.[3] As part of the Prix de Rome, David toured the newly excavated ruins of Pompeii in 1779, which deepened his belief that the persistence of classical culture was an index of its eternal conceptual and formal power. During the trip David also assiduously studied the High Renaissance painters, Raphael making a profound and lasting impression on the young French artist.

Early work

Although David's fellow students at the academy found him difficult to get along with, they recognized his genius. David's stay at the French Academy in Rome was extended by a year. In July 1780, he returned to Paris.[2] There, he found people ready to use their influence for him, and he was made an official member of the Royal Academy. He sent the Academy two paintings, and both were included in the Salon of 1781, a high honor. He was praised by his famous contemporary painters, but the administration of the Royal Academy was very hostile to this young upstart. After the Salon, the King granted David lodging in the Louvre, an ancient and much desired privilege of great artists. When the contractor of the King's buildings, M. Pécoul, was arranging with David, he asked the artist to marry his daughter, Marguerite Charlotte. This marriage brought him money and eventually four children. David had about 50 of his own pupils and was commissioned by the government to paint "Horace defended by his Father", but he soon decided, "Only in Rome can I paint Romans." His father-in-law provided the money he needed for the trip, and David headed for Rome with his wife and three of his students, one of whom, Jean-Germain Drouais (1763–1788), was the Prix de Rome winner of that year.

In Rome, David painted his famous Oath of the Horatii, 1784. In this piece, the artist references Enlightenment values while alluding to Rousseau's social contract. The republican ideal of the general became the central focus of the painting with all three sons positioned in compliance with the father. The Oath between the characters can be read as an act of unification of men to the binding of the state.[4] The issue of gender roles also becomes apparent in this piece, as the women in Horatii greatly contrast the group of brothers. David depicts the father with his back to the women, shutting them out of the oath. They also appear to be smaller in scale and physically isolated from the male figures.[5] The masculine virility and discipline displayed by the men's rigid and confident stances is also severely contrasted to the slouching, swooning female softness created in the other half of the composition.[6] Here we see the clear division of male-female attributes that confined the sexes to specific roles under Rousseau's popularized doctrine of "separate spheres".

These revolutionary ideals are also apparent in the Distribution of Eagles. While Oath of the Horatii and The Tennis Court Oath stress the importance of masculine self-sacrifice for one's country and patriotism, the Distribution of Eagles would ask for self-sacrifice for one's Emperor (Napoleon) and the importance of battlefield glory.

In 1787, David did not become the Director of the French Academy in Rome, which was a position he wanted dearly. The Count in charge of the appointments said David was too young, but said he would support him in 6 to 12 years. This situation would be one of many that would cause him to lash out at the Academy in years to come.

For the Salon of 1787, David exhibited his famous Death of Socrates. "Condemned to death, Socrates, strong, calm and at peace, discusses the immortality of the soul. Surrounded by Crito, his grieving friends and students, he is teaching, philosophizing, and in fact, thanking the God of Health, Asclepius, for the hemlock brew which will ensure a peaceful death... The wife of Socrates can be seen grieving alone outside the chamber, dismissed for her weakness. Plato is depicted as an old man seated at the end of the bed." Critics compared the Socrates with Michelangelo's Sistine Ceiling and Raphael's Stanze, and one, after ten visits to the Salon, described it as "in every sense perfect". Denis Diderot said it looked like he copied it from some ancient bas-relief. The painting was very much in tune with the political climate at the time. For this painting, David was not honored by a royal "works of encouragement".

For his next painting, David created The Lictors Bring to Brutus the Bodies of His Sons. The work had tremendous appeal for the time. Before the opening of the Salon, the French Revolution had begun. The National Assembly had been established, and the Bastille had fallen. The royal court did not want propaganda agitating the people, so all paintings had to be checked before being hung. David's portrait of Lavoisier, who was a chemist and physicist as well as an active member of the Jacobin party, was banned by the authorities for such reasons.[7] When the newspapers reported that the government had not allowed the showing of The Lictors Bring to Brutus the Bodies of His Sons, the people were outraged, and the royals were forced to give in. The painting was hung in the exhibition, protected by art students. The painting depicts Lucius Junius Brutus, the Roman leader, grieving for his sons. Brutus's sons had attempted to overthrow the government and restore the monarchy, so the father ordered their death to maintain the republic. Brutus was the heroic defender of the republic, sacrificing his own family for the good of the republic. On the right, the mother holds her two daughters, and the nurse is seen on the far right, in anguish. Brutus sits on the left, alone, brooding, seemingly dismissing the dead bodies of his sons. Knowing what he did was best for his country, but the tense posture of his feet and toes reveals his inner turmoil. The whole painting was a Republican symbol, and obviously had immense meaning during these times in France. It exemplified civic virtue, a value highly regarded during the Revolution.

The French Revolution

In the beginning, David was a supporter of the Revolution, a friend of Robespierre, and a member of the Jacobin Club. While others were leaving the country for new and greater opportunities, David stayed behind to help destroy the old order; he was a regicide who voted in the National Convention for the Execution of Louis XVI. It is uncertain why he did this, as there were many more opportunities for him under the King than the new order; some people suggest David's love for the classical made him embrace everything about that period, including a republican government.

Others believed that they found the key to the artist's revolutionary career in his personality. Undoubtedly, David's artistic sensibility, mercurial temperament, volatile emotions, ardent enthusiasm, and fierce independence might have been expected to help turn him against the established order but they did not fully explain his devotion to the republican regime. Nor did the vague statements of those who insisted upon his "powerful ambition...and unusual energy of will" actually account for his revolutionary connections. Those who knew him maintained that "generous ardor", high-minded idealism and well-meaning though sometimes fanatical enthusiasm, rather than opportunism and jealousy, motivated his activities during this period.

Soon, David turned his critical sights on the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture. This attack was probably caused primarily by the hypocrisy of the organization and their personal opposition against his work, as seen in previous episodes in David's life. The Royal Academy was controlled by royalists, who opposed David's attempts at reform; so the National Assembly finally ordered it to make changes to conform to the new constitution.

David then began work on something that would later hound him: propaganda for the new republic. David's painting of Brutus was shown during the play Brutus by Voltaire.

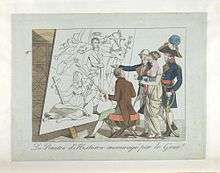

In 1789, Jacques-Louis David attempted to leave his artistic mark on the historical beginnings of the French Revolution with his painting of The Oath of the Tennis Court. David undertook this task not out of personal political conviction but rather because he was commissioned to do so. The painting was meant to commemorate the event of the same name but was never completed. A meeting of the Estates General was convened in May to address reforms of the monarchy. Dissent arose over whether the three estates would meet separately, as had been tradition, or as one body. The King's acquiescence with the demands of the upper orders led to the deputies of the Third Estate renaming themselves as the National Assembly on 17 June. They were locked out of the meeting hall three days later when they attempted to meet, and forced to reconvene to the royal indoor tennis court. Presided over by Jean-Sylvain Bailly, they made a 'solemn oath never to separate' until a national constitution had been created. In 1789 this event was seen as a symbol of the national unity against the ancien regime. Rejecting the current conditions, the oath signified a new transition in human history and ideology.[8] David was enlisted by the Society of Friends of the Constitution, the body that would eventually form the Jacobins, to enshrine this symbolic event.[9]

This instance is notable in more ways than one because it eventually led David to finally become involved in politics as he joined the Jacobins. The picture was meant to be massive in scale; the figures in the foreground were to be life-sized portraits of the counterparts, including Jean-Sylvain Bailly, the President of the Constituent Assembly. Seeking additional funding, David turned to the Society of Friends of the Constitution. The funding for the project was to come from over three thousand subscribers hoping to receive a print of the image. However, when the funding was insufficient, the state ended up financing the project.[2]

David set out in 1790 to transform the contemporary event into a major historical picture which would appear at the Salon of 1791 as a large pen-and-ink drawing. As in the Oath of the Horatii, David represents the unity of men in the service of a patriotic ideal. The outstretched arms which are prominent in both works betray David's deeply held belief that acts of republican virtue akin to those of the Romans were being played out in France. In what was essentially an act of intellect and reason, David creates an air of drama in this work. The very power of the people appears to be "blowing" through the scene with the stormy weather, in a sense alluding to the storm that would be the revolution.

Symbolism in this work of art closely represents the revolutionary events taking place at the time. The figure in the middle is raising his right arm making the oath that they will never disband until they have reached their goal of creating a "constitution of the realm fixed upon solid foundations".[10] The importance of this symbol is highlighted by the fact that the crowd's arms are angled to his hand forming a triangular shape. Additionally, the open space in the top half contrasted to the commotion in the lower half serves to emphasize the magnitude of the Tennis Court Oath.

In his attempt to depict political events of the Revolution in "real time", David was venturing down a new and untrodden path in the art world. However, Thomas Crow argues that this path "proved to be less a way forward than a cul-de-sac for history painting".[9] Essentially, the history of the demise of David's The Tennis Court Oath illustrates the difficulty of creating works of art that portray current and controversial political occurrences. Political circumstances in France proved too volatile to allow the completion of the painting. The unity that was to be symbolized in The Tennis Court Oath no longer existed in radicalized 1792. The National Assembly had split between conservatives and radical Jacobins, both vying for political power. By 1792 there was no longer consensus that all the revolutionaries at the tennis court were "heroes". A sizeable number of the heroes of 1789 had become the villains of 1792. In this unstable political climate David's work remained unfinished. With only a few nude figures sketched onto the massive canvas, David abandoned The Oath of the Tennis Court. To have completed it would have been politically unsound. After this incident, when David attempted to make a political statement in his paintings, he returned to the less politically charged use of metaphor to convey his message.

When Voltaire died in 1778, the church denied him a church burial, and his body was interred near a monastery. A year later, Voltaire's old friends began a campaign to have his body buried in the Panthéon, as church property had been confiscated by the French Government. In 1791, David was appointed to head the organizing committee for the ceremony, a parade through the streets of Paris to the Panthéon. Despite rain and opposition from conservatives due to the amount of money spent, the procession went ahead. Up to 100,000 people watched the "Father of the Revolution" being carried to his resting place. This was the first of many large festivals organized by David for the republic. He went on to organize festivals for martyrs that died fighting royalists. These funerals echoed the religious festivals of the pagan Greeks and Romans and are seen by many as Saturnalian.

David incorporated many revolutionary symbols into these theatrical performances and orchestrated ceremonial rituals, in effect radicalizing the applied arts themselves. The most popular symbol for which David was responsible as propaganda minister was drawn from classical Greek images; changing and transforming them with contemporary politics. In an elaborate festival held on the anniversary of the revolt that brought the monarchy to its knees, David's Hercules figure was revealed in a procession following the Goddess of Liberty (Marianne). Liberty, the symbol of Enlightenment ideals was here being overturned by the Hercules symbol; that of strength and passion for the protection of the Republic against disunity and factionalism.[11] In his speech during the procession, David "explicitly emphasized the opposition between people and monarchy; Hercules was chosen, after all, to make this opposition more evident".[12] The ideals that David linked to his Hercules single-handedly transformed the figure from a sign of the old regime into a powerful new symbol of revolution. "David turned him into the representation of a collective, popular power. He took one of the favorite signs of monarchy and reproduced, elevated, and monumentalized it into the sign of its opposite."[13] Hercules, the image, became to the revolutionaries, something to rally around.

In June 1791, the King made an ill-fated attempt to flee the country, but was apprehended short of his goal on the Austrian Netherlands border and was forced to return under guard to Paris. Louis XVI had made secret requests to Emperor Leopold II of Austria, Marie-Antoinette's brother, to restore him to his throne. This was granted and Austria threatened France if the royal couple were hurt. In reaction, the people arrested the King. This led to an Invasion after the trials and execution of Louis and Marie-Antoinette. The Bourbon monarchy was destroyed by the French people in 1792—it would be restored after Napoleon, then destroyed again with the Restoration of the House of Bonaparte. When the new National Convention held its first meeting, David was sitting with his friends Jean-Paul Marat and Robespierre. In the Convention, David soon earned the nickname "ferocious terrorist". Robespierre's agents discovered a secret vault containing the King's correspondence which proved he was trying to overthrow the government, and demanded his execution. The National Convention held the trial of Louis XVI; David voted for the death of the King, causing his wife, a royalist, to divorce him.

When Louis XVI was executed on 21 January 1793, another man had already died as well—Louis Michel le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau. Le Peletier was killed on the preceding day by a royal bodyguard in revenge for having voted for the death of the King. David was called upon to organize a funeral, and he painted Le Peletier Assassinated. In it, the assassin's sword was seen hanging by a single strand of horsehair above Le Peletier's body, a concept inspired by the proverbial ancient tale of the sword of Damocles, which illustrated the insecurity of power and position. This underscored the courage displayed by Le Peletier and his companions in routing an oppressive king. The sword pierces a piece of paper on which is written "I vote the death of the tyrant", and as a tribute at the bottom right of the picture David placed the inscription "David to Le Peletier. 20 January 1793". The painting was later destroyed by Le Peletier's royalist daughter, and is known by only a drawing, an engraving, and contemporary accounts. Nevertheless, this work was important in David's career because it was the first completed painting of the French Revolution, made in less than three months, and a work through which he initiated the regeneration process that would continue with The Death of Marat, David's masterpiece.

On 13 July 1793, David's friend Marat was assassinated by Charlotte Corday with a knife she had hidden in her clothing. She gained entrance to Marat's house on the pretense of presenting him a list of people who should be executed as enemies of France. Marat thanked her and said that they would be guillotined next week upon which Corday immediately fatally stabbed him. She was guillotined shortly thereafter. Corday was of an opposing political party, whose name can be seen in the note Marat holds in David's subsequent painting, The Death of Marat. Marat, a member of the National Convention and a journalist, had a skin disease that caused him to itch horribly. The only relief he could get was in his bath over which he improvised a desk to write his list of suspect counter-revolutionaries who were to be quickly tried and, if convicted, guillotined. David once again organized a spectacular funeral, and Marat was buried in the Panthéon. Marat's body was to be placed upon a Roman bed, his wound displayed and his right arm extended holding the pen which he had used to defend the Republic and its people. This concept was to be complicated by the fact that the corpse had begun to putrefy. Marat's body had to be periodically sprinkled with water and vinegar as the public crowded to see his corpse prior to the funeral on 15 and 16 July. The stench became so bad however that the funeral had to be brought forward to the evening of 16 July.[14]

The Death of Marat, perhaps David's most famous painting, has been called the Pietà of the revolution. Upon presenting the painting to the convention, he said "Citizens, the people were again calling for their friend; their desolate voice was heard: David, take up your brushes..., avenge Marat... I heard the voice of the people. I obeyed." David had to work quickly, but the result was a simple and powerful image.

The Death of Marat, 1793, became the leading image of the Terror and immortalized both Marat and David in the world of the revolution. This piece stands today as "a moving testimony to what can be achieved when an artist's political convictions are directly manifested in his work".[15] A political martyr was instantly created as David portrayed Marat with all the marks of the real murder, in a fashion which greatly resembles that of Christ or his disciples.[16] The subject although realistically depicted remains lifeless in a rather supernatural composition. With the surrogate tombstone placed in front of him and the almost holy light cast upon the whole scene; alluding to an out of this world existence. "Atheists though they were, David and Marat, like so many other fervent social reformers of the modern world, seem to have created a new kind of religion."[17] At the very center of these beliefs, there stood the republic.

After the King's execution, war broke out between the new Republic and virtually every major power in Europe. David, as a member of the Committee of General Security, contributed directly to the Reign of Terror.[18] David organized his last festival: the festival of the Supreme Being. Robespierre had realized what a tremendous propaganda tool these festivals were, and he decided to create a new religion, mixing moral ideas with the Republic and based on the ideas of Rousseau. This process had already begun by confiscating church lands and requiring priests to take an oath to the state. The festivals, called fêtes, would be the method of indoctrination. On the appointed day, 20 Prairial by the revolutionary calendar, Robespierre spoke, descended steps, and with a torch presented to him by David, incinerated a cardboard image symbolizing atheism, revealing an image of wisdom underneath.

Soon, the war began to go well; French troops marched across the southern half of the Netherlands (which would later become Belgium), and the emergency that had placed the Committee of Public Safety in control was no more. Then plotters seized Robespierre at the National Convention and he was later guillotined, in effect ending the Reign of Terror. As Robespierre was arrested, David yelled to his friend "if you drink hemlock, I shall drink it with you."[19] After this, he supposedly fell ill, and did not attend the evening session because of "stomach pain", which saved him from being guillotined along with Robespierre. David was arrested and placed in prison, first from 2 August to 28 December 1794 and then from 29 May to 3 August 1795.[2] There he painted his own portrait, showing him much younger than he actually was, as well as that of his jailer.

Post-revolution

After David's wife visited him in jail, he conceived the idea of telling the story of The rape of the Sabine women. The Sabine Women Enforcing Peace by Running between the Combatants, also called The Intervention of the Sabine Women is said to have been painted to honor his wife, with the theme being love prevailing over conflict. The painting was also seen as a plea for the people to reunite after the bloodshed of the revolution.[20]

David conceived a new style for this painting, one which he called the "Pure Greek Style", as opposed to the "Roman style" of his earlier historical paintings. The new style was influenced heavily by the work of art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann. In David's words, "the most prominent general characteristics of the Greek masterpieces are a noble simplicity and silent greatness in pose as well as in expression."[21] Instead of the muscularity and angularity of the figures of his past works, these were more air-brushed, feminine, and painterly.

This work also brought him to the attention of Napoleon. The story for the painting is as follows: "The Romans have abducted the daughters of their neighbors, the Sabines. To avenge this abduction, the Sabines attacked Rome, although not immediately—since Hersilia, the daughter of Tatius, the leader of the Sabines, had been married to Romulus, the Roman leader, and then had two children by him in the interim. Here we see Hersilia between her father and husband as she adjures the warriors on both sides not to take wives away from their husbands or mothers away from their children. The other Sabine Women join in her exhortations." During this time, the martyrs of the Revolution were taken from the Pantheon and buried in common ground, and revolutionary statues were destroyed. When David was finally released to the country, France had changed. His wife managed to get him released from prison, and he wrote letters to his former wife, and told her he never ceased loving her. He remarried her in 1796. Finally, wholly restored to his position, he retreated to his studio, took pupils and for the most part, retired from politics.

In August 1796, David and many other artists signed a petition orchestrated by Quatremère de Quincy which questioned the wisdom of the planned seizure of works of art from Rome. The Director Barras believed that David was "tricked" into signing, although one of David's students recalled that in 1798 his master lamented the fact that masterpieces had been imported from Italy.

Napoleon

David's close association with the Committee of Public Safety during the Terror resulted in his signing of the death warrant for Alexandre de Beauharnais, a minor noble. Beauharnais's widow, Joséphine, went on to marry Napoleon Bonaparte and became his empress; David himself depicted their coronation in the Coronation of Napoleon and Josephine, 2 December 1804.

David had been an admirer of Napoleon from their first meeting, struck by Bonaparte's classical features. Requesting a sitting from the busy and impatient general, David was able to sketch Napoleon in 1797. David recorded the face of the conqueror of Italy, but the full composition of Napoleon holding the peace treaty with Austria remains unfinished. This was likely a decision by Napoleon himself after considering the current political situation. He may have considered the publicity the portrait would bring about to be ill-timed. Bonaparte had high esteem for David, and asked him to accompany him to Egypt in 1798, but David refused, seemingly unwilling to give up the material comfort, safety, and peace of mind he had obtained through the years. Draftsman and engraver Dominique Vivant Denon went to Egypt instead, providing mostly documentary and archaeological work.[22]

After Napoleon's successful coup d'état in 1799, as First Consul he commissioned David to commemorate his daring crossing of the Alps. The crossing of the St. Bernard Pass had allowed the French to surprise the Austrian army and win victory at the Battle of Marengo on 14 June 1800. Although Napoleon had crossed the Alps on a mule, he requested that he be portrayed "calm upon a fiery steed". David complied with Napoleon Crossing the Saint-Bernard. After the proclamation of the Empire in 1804, David became the official court painter of the regime. During this period he took students, one of whom was the Belgian painter Pieter van Hanselaere.

.jpg)

One of the works David was commissioned for was The Coronation of Napoleon (1805-1807). David was permitted to watch the event. He had plans of Notre Dame delivered and participants in the coronation came to his studio to pose individually, though never the Emperor (the only time David obtained a sitting from Napoleon had been in 1797). David did manage to get a private sitting with the Empress Joséphine and Napoleon's sister, Caroline Murat, through the intervention of erstwhile art patron Marshal Joachim Murat, the Emperor's brother-in-law. For his background, David had the choir of Notre Dame act as his fill-in characters. Pope Pius VII came to sit for the painting, and actually blessed David. Napoleon came to see the painter, stared at the canvas for an hour and said "David, I salute you." David had to redo several parts of the painting because of Napoleon's various whims, and for this painting, he received twenty-four thousand Francs.

David was made a Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur in 1803. He was promoted to an Officier in 1808. And, in 1815, he was promoted to a Commandant (now Commandeur) de la Légion d'honneur.

Exile and death

On the Bourbons returning to power, David figured in the list of proscribed former revolutionaries and Bonapartists—for having voted execution for the deposed King Louis XVI; and for participating in the death of Louis XVII. Mistreated and starved, the imprisoned Louis XVII was forced into a false confession of incest with his mother, Queen Marie-Antoinette. This was untrue, as the son was separated from his mother early and was not allowed communication with her; nevertheless, the allegation helped earn her the guillotine. The newly restored Bourbon King, Louis XVIII, however, granted amnesty to David and even offered him the position of court painter. David refused, preferring self-exile in Brussels. There, he trained and influenced Brussels artists like François-Joseph Navez and Ignace Brice, painted Cupid and Psyche and quietly lived the remainder of his life with his wife (whom he had remarried). In that time, he painted smaller-scale mythological scenes, and portraits of citizens of Brussels and Napoleonic émigrés, such as the Baron Gerard.

David created his last great work, Mars Being Disarmed by Venus and the Three Graces, from 1822 to 1824. In December 1823, he wrote: "This is the last picture I want to paint, but I want to surpass myself in it. I will put the date of my seventy-five years on it and afterwards I will never again pick up my brush." The finished painting—evoking painted porcelain because of its limpid coloration—was exhibited first in Brussels, then in Paris, where his former students flocked to view it.

The exhibition was profitable—13,000 francs, after deducting operating costs, thus, more than 10,000 people visited and viewed the painting. In his later years, David remained in full command of his artistic faculties, even after a stroke in the spring of 1825 disfigured his face and slurred his speech. In June 1825, he resolved to embark on an improved version of his Anger of Achilles (also known as the Sacrifice of Iphigenie); the earlier version was completed in 1819 and is now in the collection of the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. David remarked to his friends who visited his studio "this [painting] is what is killing me" such was his determination to complete the work, but by October it must have already been well advanced, as his former pupil Gros wrote to congratulate him, having heard reports of the painting's merits. By the time David died, the painting had been completed and the commissioner Ambroise Firmin-Didot brought it back to Paris to include it in the exhibition "Pour les grecs" that he had organised and which opened in Paris in April 1826.

When David was leaving a theater, a carriage struck him, and he later died, on 29 December 1825. At his death, some portraits were auctioned in Paris, they sold for little; the famous Death of Marat was exhibited in a secluded room, to avoid outraging public sensibilities. Disallowed return to France for burial, for having been a regicide of King Louis XVI, the body of the painter Jacques-Louis David was buried in Brussels and moved in 1882 to Brussels Cemetery, while some say his heart was buried with his wife at Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris.

Freemasonry

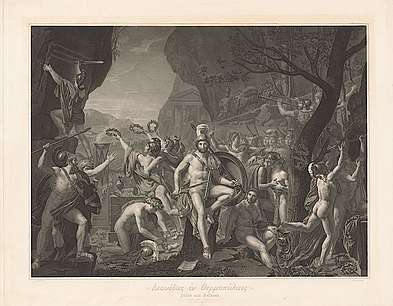

The theme of the oath found in several works like The Oath of the Tennis Court, The Distribution of the Eagles, and Leonidas at Thermopylae, was perhaps inspired by the rituals of Freemasonry. In 1989 during the "David against David" conference Albert Boime was able to prove, on the basis of a document dated in 1787, the painter's membership in the "La Moderation" Masonic Lodge.[23][24]

Medical analysis of David's face

Jacques-Louis David's facial abnormalities were traditionally reported to be a consequence of a deep facial sword wound after a fencing incident. These left him with a noticeable asymmetry during facial expression and resulted in his difficulty in eating or speaking (he could not pronounce some consonants such as the letter 'r'). A sword scar wound on the left side of his face is present in his self-portrait and sculptures and corresponds to some of the buccal branches of the facial nerve. An injury to this nerve and its branches are likely to have resulted in the difficulties with his left facial movement.

Furthermore, as a result of this injury, he suffered from a growth on his face that biographers and art historians have defined as a benign tumor. These, however, may have been a granuloma, or even a post-traumatic neuroma.[25] As historian Simon Schama has pointed out, witty banter and public speaking ability were key aspects of the social culture of 18th-century France. In light of these cultural keystones, David's tumor would have been a heavy obstacle in his social life.[26] David was sometimes referred to as "David of the Tumor".[27]

Portraiture

In addition to his history paintings, David completed a number of privately commissioned portraits. Warren Roberts, among others, has pointed out the contrast between David's "public style" of painting, as shown in his history paintings, and his "private style", as shown in his portraits.[28] His portraits were characterized by a sense of truth and realism. He focused on defining his subjects' features and characters without idealizing them.[29] This is different from the style seen in his historical paintings, in which he idealizes his figures' features and bodies to align with Greek and Roman ideals of beauty.[30] He puts a great deal of detail into his portraits, defining smaller features like hands and fabric. The compositions of his portraits remain simple with blank backgrounds that allow the viewer to focus on the details of the subject.

The portrait he did of his wife (1813) is an example of his typical portrait style.[28] The background is dark and simple without any clues as to the setting, which forces the viewer to focus entirely on her. Her features are un-idealized and truthful to her appearance.[28] There is a great amount of detail that can be seen in his attention to portraying the satin material of the dress she wears, the drapery of the scarf around her, and her hands which rest in her lap.

In the painting of Brutus (1789), the man and his wife are separated, both morally and physically. Paintings like these, depicting the great strength of patriotic sacrifice, made David a popular hero of the revolution.[28]

In the Portrait of Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier and his wife (1788), the man and his wife are tied together in an intimate pose. She leans on his shoulder while he pauses from his work to look up at her. David casts them in a soft light, not in the sharp contrast of Brutus or of the Horatii. Also of interest—Lavoisier was a tax collector, as well as a famous chemist. Though he spent some of his money trying to clean up swamps and eradicate malaria, he was nonetheless sent to the guillotine during the Reign of Terror as an enemy of the people. David, then a powerful member of the National Assembly, stood idly by and watched.[31]

Other portraits include paintings of his sister-in-law and her husband, Madame and Monsieur Seriziat. The picture of Monsieur Seriziat depicts a man of wealth, sitting comfortably with his horse-riding equipment. The picture of the Madame shows her wearing an unadorned white dress, holding her young child's hand as they lean against a bed. David painted these portraits of Madame and Monsieur Seriziat out of gratitude for letting him stay with them after he was in jail.[32]

Towards the end of David's life, he painted a portrait of his old friend Abbé Sieyès. Both had been involved in the Revolution, both had survived the purging of political radicals that followed the reign of terror.

Shift in attitude

The shift in David's perspective played an important role in the paintings of David's later life, including this one of Sieyès.[33] During the height of The Terror, David was an ardent supporter of radicals such as Robespierre and Marat, and twice offered up his life in their defense. He organized revolutionary festivals and painted portraits of martyrs of the revolution, such as Lepeletier, who was assassinated for voting for the death of the king. David was an impassioned speaker at times in the National Assembly. In speaking to the Assembly about the young boy named Bara, another martyr of the revolution, David said, "O Bara! O Viala! The blood that you have spread still smokes; it rises toward Heaven and cries for vengeance."[34]

After Robespierre was sent to the guillotine, however, David was imprisoned and changed the attitude of his rhetoric. During his imprisonment he wrote many letters, pleading his innocence. In one he wrote, "I am prevented from returning to my atelier, which, alas, I should never have left. I believed that in accepting the most honorable position, but very difficult to fill, that of legislator, that a righteous heart would suffice, but I lacked the second quality, understanding."[35]

Later, while explaining his developing "Grecian style" for paintings such as The Intervention of the Sabine Women, David further commented on a shift in attitude: "In all human activity the violent and transitory develops first; repose and profundity appear last. The recognition of these latter qualities requires time; only great masters have them, while their pupils have access only to violent passions."[36]

Legacy

Jacques-Louis David was, in his time, regarded as the leading painter in France, and arguably all of Western Europe; many of the painters honored by the restored Bourbons following the French Revolution had been David's pupils.[37] David's student Antoine-Jean Gros for example, was made a Baron and honored by Napoleon Bonaparte's court.[37] Another pupil of David's, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres became the most important artist of the restored Royal Academy and the figurehead of the Neoclassical school of art, engaging the increasingly popular Romantic school of art that was beginning to challenge Neoclassicism.[37] David invested in the formation of young artists for the Rome Prize, which was also a way to pursue his old rivalry with other contemporary painters such as Joseph-Benoît Suvée, who had also started teaching classes.[38] To be one of David's students was considered prestigious and earned his students a lifetime reputation.[39] He also called on the more advanced students, such as Jérôme-Martin Langlois, to help him paint his large canvases.

Despite David's reputation, he was more fiercely criticized right after his death than at any point during his life. His style came under the most serious criticism for being static, rigid, and uniform throughout all his work. David's art was also attacked for being cold and lacking warmth.[40] David, however, made his career precisely by challenging what he saw as the earlier rigidity and conformity of the French Royal Academy's approach to art.[41] David's later works also reflect his growth in the development of the Empire style, notable for its dynamism and warm colors. It is likely that much of the criticism of David following his death came from David's opponents; during his lifetime David made a great many enemies with his competitive and arrogant personality as well as his role in the Terror.[39] David sent many people to the guillotine and personally signed the death warrants for King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. One significant episode in David's political career that earned him a great deal of contempt was the execution of Emilie Chalgrin. A fellow painter Carle Vernet had approached David, who was on the Committee of Public Safety, requesting him to intervene on behalf of his sister, Chalgrin. She had been accused of crimes against the Republic, most notably possessing stolen items.[42] David refused to intervene in her favor, and she was executed. Vernet blamed David for her death, and the episode followed him for the rest of his life and after.

In the last 50 years David has enjoyed a revival in popular favor and in 1948 his two-hundredth birthday was celebrated with an exhibition at the Musée de l'Orangerie in Paris and at Versailles showing his life's works.[43] Following World War II, Jacques-Louis David was increasingly regarded as a symbol of French national pride and identity, as well as a vital force in the development of European and French art in the modern era.[44]

The birth of Romanticism is traditionally credited to the paintings of eighteenth-century French artists such as Jacques-Louis David.[45]

Filmography

Danton (Andrzej Wajda, France, 1982) – Historical drama. Many scenes include David as a silent character watching and drawing. The film focuses on the period of the Terror.

Gallery

Diana and Apollo Piercing Niobe's Children with their Arrows (1772), Dallas Museum of Art

Diana and Apollo Piercing Niobe's Children with their Arrows (1772), Dallas Museum of Art Antiochus and Stratonica (1774), École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts

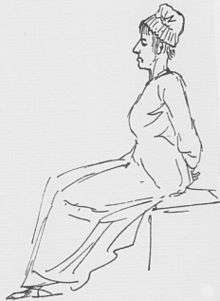

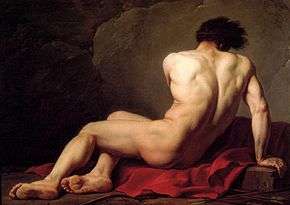

Antiochus and Stratonica (1774), École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts Patroclus, study (1780), Musée Thomas-Henry

Patroclus, study (1780), Musée Thomas-Henry Hector's body (1778)

Hector's body (1778) Portrait of Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier and his wife (1788), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Portrait of Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier and his wife (1788), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Portrait of Anne-Marie-Louise Thélusson, Comtesse de Sorcy (1790), Neue Pinakothek, Munich

Portrait of Anne-Marie-Louise Thélusson, Comtesse de Sorcy (1790), Neue Pinakothek, Munich Portrait of Pierre Sériziat, (1795), Louvre Museum

Portrait of Pierre Sériziat, (1795), Louvre Museum Portrait of Madame de Verninac (1798–1799), born Henriette Delacroix, elder sister of Eugène Delacroix, Musée du Louvre, Paris

Portrait of Madame de Verninac (1798–1799), born Henriette Delacroix, elder sister of Eugène Delacroix, Musée du Louvre, Paris Madame Récamier (1800), Musée du Louvre, Paris

Madame Récamier (1800), Musée du Louvre, Paris Suzanne Le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau (1804), The J. Paul Getty Museum

Suzanne Le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau (1804), The J. Paul Getty Museum Portrait of Pope Pius VII (1805), Musée du Louvre, Paris

Portrait of Pope Pius VII (1805), Musée du Louvre, Paris- Marguerite-Charlotte David (1813), National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Étienne-Maurice Gérard (1816), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Étienne-Maurice Gérard (1816), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York The Comtesse Vilain XIIII and Her Daughter (1816), National Gallery, London

The Comtesse Vilain XIIII and Her Daughter (1816), National Gallery, London Portrait of the Comte de Turenne (1816), Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen

Portrait of the Comte de Turenne (1816), Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen

See also

References

- Matthew Collings. "Feelings". This Is Civilisation. Season 1. Episode 2. 2007.

- Lee, Simon. "David, Jacques-Louis." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. 14 November 2014.<http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T021541>.

- Alex Potts, Flesh and the Ideal: Winckelmann and the Origins of Art History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000).

- Boime 1987, p. 394.

- Boime 1987, p. 399.

- Boime 1987, p. 398.

- Honour 1977, p. 72.

- Roberts, Warren (2000). Jaques-Louis David and Jean-Louis Prieur revolutionary artists : the public, the populace, and images of the French revolution. New York: State university of New York press. p. 229. ISBN 0791442888.

- Crow 2007.

- Bordes 2005, p. ??.

- Hunt 2004, p. 97.

- Hunt 2004, p. 99.

- Hunt 2004, p. 103.

- Schama 1989, p. 83.

- Boime 1987, p. 454.

- Rosenblum 1969, p. 83.

- Janson & Rosenblum 1984, p. 30.

- Boime 1987, p. 442.

- Carlyle, p. 384.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 90–112.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 90–115.

- Bordes, Philippe (2005). Jacques-Louis David: Empire to Exile. Yale University Press. pp. 26-28. ISBN 978-0300104479. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- Les thèmes du serment, David et la Franc-maçonnerie; page 83 (Boime, 1989)

- Le Paris des Francs- Maçons (Emmanuel Pierret, Laurent Kupferman - 2013 - ed. Cherche midi)

- Ashrafian, H. Jacques-Louis David and his post-traumatic facial pathology. J R Soc Med 2007;100:341-342.

- Schama, Simon. The Power of Art: Jacques-Louis David. https://www.bbc.co.uk/arts/powerofart/david.shtml

- Roberts 1992, pp. 1–30.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 42–45.

- Bordes, Phillip. “Jacques-Louis David: Empire to Exile.” New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007.

- Wilson, Elizabeth Barkley. "Jacques-Louis David." Smithsonian 29, no. 5 (August 1998): 80. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed 18 November 2017).

- Roberts 1992, pp. 43–45.

- Lajer-Burcharth, Ewa. “Necklines: The Art of Jacques-Louis David After the Terror.” New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 90–150.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 88–92.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 90–94.

- Roberts 1992, pp. 100–112.

- Lee, Simon. David. p. 321.

- P. Bordes, Jacques-Louis David:Empire to Exile. Yale University Press, 2005

- Lee, Simon. David. pp. 321–322.

- Lee, Simon. David. p. 322.

- Roberts 1992, p. 14.

- Lee, Simon. David. p. 151.

- Lee, Simon. David. p. 326.

- Lee, Simon. David. p. 328.

- Lee Palmer, Allison. Historical Dictionary of Romantic Art and Architecture. p. 304.

- Sloane, J. C., Wisdom, J. M., & William Hayes Ackland Memorial Art Center. 1978. French Nineteenth Century Oil Sketches: David to Degas. Chapel Hill, N.C: The University. p. 50

Sources

- Boime, Albert (1987), Social History of Modern Art: Art in the Age of Revolution, 1750–1800 volume 1, Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-06332-1

- Bordes, Philippe (1988), David, Paris, FRA: Hazan, ISBN 2-85025-173-9

- Bordes, Philippe (2005), Jacques-Louis David: From Empire to Exile, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-10447-2

- Brookner, Anita, Jacques-Louis David, Chatto & Windus (1980)

- Carlyle, Thomas (1860) [1837]. The French Revolution: A History. II. New York: Harper & Bros. OCLC 14208955.

- Chodorow, Stanley, et al. The Mainstream of Civilization. New York: The Harcourt Press (1994) pg. 594

- Crow, Thomas E. (1995), Emulation: Making Artists for Revolutionary France (1st ed.), New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-06093-9

- Crow, Thomas E. (2007), "Patriotism and Virtue: David to the Young Ingres", in Eisenman, Stephen F. (ed.), Nineteenth Century Art: A Critical History (3rd ed.), New York City, New York: Thames & Hudson, pp. 18–54, ISBN 0-500-28683-3

- Delécluze, E., Louis David, son école et son temps, Paris, (1855) re-edition Macula (1983)

- Dowd, David, Pageant-Master of the Republic, Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, (1948)

- Honour, Hugh (1977), Neo-Classicism, New York City, New York: Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-013760-2

- Humbert, Agnès, Louis David, peintre et conventionnel: essai de critique marxiste, Paris, Editions sociales internationales (1936)

- Humbert, Agnès, Louis David, collection des Maîtres, 60 illustrations, Paris, Braun (1940)

- Hunt, Lynn (2004), Politics, Culture, and Class in the French Revolution, Los Angeles, California: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-24156-8

- Janson, Horst Waldemar; Rosenblum, Robert (1984), 19th-Century Art, New York City, New York: Harry Abrams, ISBN 0-13-622621-3

- Johnson, Dorothy, Jacques-Louis David. New Perspectives, Newark (2006)

- Lajer-Burcharth, Ewa, Necklines. The art of Jacques-Louis David after the Terror, ed. Yale University Press, New Haven London (1999)

- Lee, Simon, David, Phaidon, London (1999). ISBN 0714838047

- Lévêque, Jean-Jacques, Jacques-Louis David édition Acr Paris (1989)

- Leymarie, Jean, French Painting, the 19th century, Cleveland (1962)

- Lindsay, Jack, Death of the Hero, London, Studio Books (1960)

- Malvone, Laura, L'Évènement politique en peinture. A propos du Marat de David in Mélanges de l'École française de Rome, Italie et Méditerranée 106, 1 (1994)

- Michel, R. (ed), David contre David, actes du colloque au Louvre du 6-10 décembre 1989, Paris (1993)

- Monneret, Sophie Monneret, David et le néoclassicisme, ed. Terrail, Paris (1998)

- Noël, Bernard, David, éd. Flammarion, Paris (1989)

- Rosenblum, Robert (1969), Transformations in Late Eighteenth Century Art (1st paperback ed.), Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-00302-5

- Roberts, Warren (1 February 1992), Jacques-Louis David, Revolutionary Artist: Art, Politics, and the French Revolution, The University of North Carolina Press, ISBN 0-8078-4350-4

- Rosenberg, Pierre, Prat, Louis-Antoine, Jacques-Louis David 1748-1825. Catalogue raisonné des dessins, 2 volumes, éd. Leonardo Arte, Milan (2002)

- Rosenberg, Pierre, Peronnet, Benjamin, Un album inédit de David in Revue de l'art, n°142 (2003–04), pp. 45–83 (complete the previous reference)

- Sahut, Marie-Catherine & Michel, Régis, David, l'art et le politique, coll. "Découvertes Gallimard" (nº 46), série Peinture. Éditions Gallimard et RMN Paris (1988)

- Sainte-Fare Garnot, N., Jacques-Louis David 1748-1825, Paris, Ed. Chaudun (2005)

- Schama, Simon (1989). Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. Penguin Books.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schnapper, Antoine, David témoin de son temps, Office du Livre, Fribourg, (1980)

- Thévoz, Michel, Le théâtre du crime. Essai sur la peinture de David, éd. de Minuit, Paris (1989)

- Vanden Berghe, Marc, Plesca, Ioana, Nouvelles perspectives sur la Mort de Marat: entre modèle jésuite et références mythologiques, Bruxelles (2004) / New Perspectives on David's Death of Marat, Brussels (2004) - online on www.art-chitecture.net/publications.php

- Vanden Berghe, Marc, Plesca, Ioana, Lepelletier de Saint-Fargeau sur son lit de mort par Jacques-Louis David: saint Sébastien révolutionnaire, miroir multiréférencé de Rome, Brussels (2005) - online on www.art-chitecture.net/publications.php

- Vaughan, William and Weston, Helen (eds),Jacques-Louis David's Marat, Cambridge (2000)

- The Death of Socrates. Retrieved 29 June 2005. New York Med.

- Jacques-Louis David, on An Abridged History of Europe. Retrieved 29 June 2005

- J.L. David on CGFA. Retrieved 29 June 2005

Further reading

- French painting 1774-1830: the Age of Revolution. New York; Detroit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art; The Detroit Institute of Arts. 1975. (see index)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jacques-Louis David. |

- A Closer Look at David's Consecration of Napoleon multimedia feature; Louvre museum official website

- The Intervention of the Sabines (Louvre museum)

- Web Gallery of Art

- www.jacqueslouisdavid.org 101 paintings by Jacques-Louis David

- Jacques-Louis David at Olga's Gallery

- Jacques-Louis David in the "History of Art"

- smARThistory: Death of Socrates

- Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute 2005 exhibition, Jacques-Louis David: Empire to Exile

- The equestrian portrait of Stanislaw Kostka Potocki at the Wilanow Palace Museum