Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More,[7][8] was an English lawyer, social philosopher, author, statesman, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VIII as Lord High Chancellor of England from October 1529 to May 1532.[9] He wrote Utopia, published in 1516,[10] about the political system of an imaginary island state.

Sir Thomas More | |

|---|---|

Sir Thomas More (1527) by Hans Holbein the Younger | |

| Lord Chancellor | |

| In office October 1529 – May 1532 | |

| Monarch | Henry VIII |

| Preceded by | Thomas Wolsey |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Audley |

| Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster | |

| In office 31 December 1525 – 3 November 1529 | |

| Monarch | Henry VIII |

| Preceded by | Richard Wingfield |

| Succeeded by | William FitzWilliam |

| Speaker of the House of Commons | |

| In office 15 April 1523 – 13 August 1523 | |

| Monarch | Henry VIII |

| Preceded by | Thomas Nevill |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Audley |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 7 February 1478 London, England |

| Died | 6 July 1535 (aged 57) London, England |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | Margaret, Elizabeth, Cicely, and John |

| Parents | Sir John More Agnes Graunger |

| Signature |  |

Philosophy career | |

Notable work | Utopia (1516) Responsio ad Lutherum (1523) A Dialogue of Comfort against Tribulation (1553) |

| Era | Renaissance philosophy 16th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Christian humanism[1] Renaissance humanism |

Main interests | Social philosophy Criticism of Protestantism |

Notable ideas | Utopia |

Influenced

| |

Saint Thomas More | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Saint Thomas More, executed on Tower Hill (London) in 1535, apparently based on the Holbein portrait. | |

| Martyr | |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church Anglican Communion |

| Beatified | 29 December 1886, Florence, Kingdom of Italy, by Pope Leo XIII |

| Canonized | 19 May 1935, Vatican City, by Pope Pius XI |

| Major shrine | Church of St Peter ad Vincula, London, England |

| Feast | 22 June (Catholic Church) 6 July (Church of England) 9 July (Catholic Extraordinary Form) |

| Attributes | dressed in the robe of the Chancellor and wearing the Collar of Esses; axe |

| Patronage | Adopted children; civil servants; court clerks; difficult marriages; large families; lawyers, politicians, and statesmen; stepparents; widowers; Ateneo de Manila Law School; Diocese of Arlington; Diocese of Pensacola-Tallahassee; Kerala Catholic Youth Movement; University of Malta; University of Santo Tomas Faculty of Arts and Letters |

More opposed the Protestant Reformation, directing polemics against the theology of Martin Luther, Huldrych Zwingli, John Calvin and William Tyndale. More also opposed Henry VIII's separation from the Catholic Church, refusing to acknowledge Henry as supreme head of the Church of England and the annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. After refusing to take the Oath of Supremacy, he was convicted of treason and executed. On his execution, he was reported to have said: "I die the King's good servant, and God's first".

Pope Pius XI canonised More in 1935 as a martyr. Pope John Paul II in 2000 declared him the patron saint of statesmen and politicians.[11][12] The Soviet Union in the early twentieth century honoured him for the purportedly communist attitude toward property rights in Utopia.[13][14][15]

Early life

Born on Milk Street in London, on 7 February 1478, Thomas More was the son of Sir John More,[16] a successful lawyer and later a judge[17], and his wife Agnes (née Graunger). He was the second of six children. More was educated at St Anthony's School, then considered one of London's best schools.[18][19] From 1490 to 1492, More served John Morton, the Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Chancellor of England, as a household page.[20]:xvi Morton enthusiastically supported the "New Learning" (scholarship which was later known as "humanism" or "London humanism"), and thought highly of the young More. Believing that More had great potential, Morton nominated him for a place at the University of Oxford (either in St. Mary Hall or Canterbury College, both now gone).[21]:38

More began his studies at Oxford in 1492, and received a classical education. Studying under Thomas Linacre and William Grocyn, he became proficient in both Latin and Greek. More left Oxford after only two years—at his father's insistence—to begin legal training in London at New Inn, one of the Inns of Chancery.[20]:xvii[22] In 1496, More became a student at Lincoln's Inn, one of the Inns of Court, where he remained until 1502, when he was called to the Bar.[20]:xvii

Spiritual life

According to his friend, theologian Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam, More once seriously contemplated abandoning his legal career to become a monk.[23][24] Between 1503 and 1504 More lived near the Carthusian monastery outside the walls of London and joined in the monks' spiritual exercises. Although he deeply admired their piety, More ultimately decided to remain a layman, standing for election to Parliament in 1504 and marrying the following year.[20]:xxi

More continued ascetic practices for the rest of his life, such as wearing a hair shirt next to his skin and occasionally engaging in flagellation.[20]:xxi A tradition of the Third Order of Saint Francis honours More as a member of that Order on their calendar of saints.[25]

Family life

More married Jane Colt in 1505.[21]:118 Erasmus reported that More wanted to give his young wife a better education than she had previously received at home, and tutored her in music and literature.[21]:119 The couple had four children before Jane died in 1511: Margaret, Elizabeth, Cicely, and John.[21]:132

Going "against friends' advice and common custom," within thirty days More had married one of the many eligible women among his wide circle of friends.[26][27] He chose Alice Middleton, a widow, to head his household and care for his small children.[28] The speed of the marriage was so unusual that More had to get a dispensation from the banns of marriage, which, due to his good public reputation, he easily obtained.[26]

More had no children from his second marriage, although he raised Alice's daughter from her previous marriage as his own. More also became the guardian of two young girls: Anne Cresacre would eventually marry his son, John More;[21]:146 and Margaret Giggs (later Clement) would be the only member of his family to witness his execution (she died on the 35th anniversary of that execution, and her daughter married More's nephew William Rastell). An affectionate father, More wrote letters to his children whenever he was away on legal or government business, and encouraged them to write to him often.[21]:150[29]:xiv

More insisted upon giving his daughters the same classical education as his son, an unusual attitude at the time.[21]:146–47 His eldest daughter, Margaret, attracted much admiration for her erudition, especially her fluency in Greek and Latin.[21]:147 More told his daughter of his pride in her academic accomplishments in September 1522, after he showed the bishop a letter she had written:

When he saw from the signature that it was the letter of a lady, his surprise led him to read it more eagerly … he said he would never have believed it to be your work unless I had assured him of the fact, and he began to praise it in the highest terms … for its pure Latinity, its correctness, its erudition, and its expressions of tender affection. He took out at once from his pocket a portague [A Portuguese gold coin] … to send to you as a pledge and token of his good will towards you.[29]:152

More's decision to educate his daughters set an example for other noble families. Even Erasmus became much more favourable once he witnessed their accomplishments.[21]:149

A portrait of More and his family, Sir Thomas More and Family, was painted by Holbein, but it was lost in a fire in the 18th century. More's grandson commissioned a copy, of which two versions survive.

Early political career

In 1504 More was elected to Parliament to represent Great Yarmouth, and in 1510 began representing London.[30]

From 1510, More served as one of the two undersheriffs of the City of London, a position of considerable responsibility in which he earned a reputation as an honest and effective public servant. More became Master of Requests in 1514,[31] the same year in which he was appointed as a Privy Counsellor.[32] After undertaking a diplomatic mission to the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, accompanying Thomas Wolsey, Cardinal Archbishop of York, to Calais and Bruges, More was knighted and made under-treasurer of the Exchequer in 1521.[32]

As secretary and personal adviser to King Henry VIII, More became increasingly influential: welcoming foreign diplomats, drafting official documents, and serving as a liaison between the King and Lord Chancellor Wolsey. More later served as High Steward for the universities of Oxford and Cambridge.

In 1523 More was elected as knight of the shire (MP) for Middlesex and, on Wolsey's recommendation, the House of Commons elected More its Speaker.[32] In 1525 More became Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, with executive and judicial responsibilities over much of northern England.[32]

Chancellorship

After Wolsey fell, More succeeded to the office of Lord Chancellor in 1529. He dispatched cases with unprecedented rapidity.

Campaign against the Protestant Reformation

More supported the Catholic Church and saw the Protestant Reformation as heresy, a threat to the unity of both church and society. More believed in the theology, argumentation, and ecclesiastical laws of the church, and "heard Luther's call to destroy the Catholic Church as a call to war."[33]

His early actions against the Protestant Reformation included aiding Wolsey in preventing Lutheran books from being imported into England, spying on and investigating suspected Protestants,[34] especially publishers, and arresting anyone holding in his possession, transporting, or distributing Bibles and other materials of the Protestant Reformation. More vigorously suppressed Tyndale's English translation of the New Testament.[35]

The Tyndale Bible used controversial translations of certain words that More considered heretical and seditious; for example, it used "senior" and "elder" rather than "priest" for the Greek "presbyteros", and used the term congregation instead of church;[36] he also pointed out that some of the marginal glosses challenged Catholic doctrine.[37] It was during this time that most of his literary polemics appeared.

Many accounts circulated during and after More's lifetime regarding persecution of the Protestant heretics during his time as Lord Chancellor. The popular sixteenth-century English Protestant historian John Foxe, who "placed Protestant sufferings against the background of... the Antichrist",[38] was instrumental in publicising accusations of torture in his famous Book of Martyrs, claiming that More had often personally used violence or torture while interrogating heretics. Later authors such as Brian Moynahan and Michael Farris cite Foxe when repeating these allegations.[39] Peter Ackroyd also lists claims from Foxe's Book of Martyrs and other post-Reformation sources that More "tied heretics to a tree in his Chelsea garden and whipped them", that "he watched as 'newe men' were put upon the rack in the Tower and tortured until they confessed", and that "he was personally responsible for the burning of several of the 'brethren' in Smithfield."[40] Richard Marius records a similar claim, which tells about James Bainham, and writes that "the story Foxe told of Bainham's whipping and racking at More's hands is universally doubted today".[41] More himself denied these allegations:

Stories of a similar nature were current even in More's lifetime and he denied them forcefully. He admitted that he did imprison heretics in his house – 'theyr sure kepynge' – he called it – but he utterly rejected claims of torture and whipping... 'as help me God.'[21]:298–299

More instead claims in his "Apology" (1533) that he only applied corporal punishment to two heretics: a child who was caned in front of his family for heresy regarding the Eucharist, and a "feeble-minded" man who was whipped for disrupting prayers.[42]:404 During More's chancellorship, six people were burned at the stake for heresy; they were Thomas Hitton, Thomas Bilney, Richard Bayfield, John Tewkesbury, Thomas Dusgate, and James Bainham.[21]:299–306 Moynahan has shown that More was influential in the burning of Tyndale, as More's agents had long pursued him, even though this took place over a year after his own death.[43] Burning at the stake had been a standard punishment for heresy, though only thirty burnings had taken place in the entire century before More's elevation to Chancellor, and burning continued to be used by both Catholics and Protestants during the religious upheaval of the following decades.[44] Ackroyd notes that More zealously "approved of burning".[21]:298 Marius maintains that More did everything in his power to bring about the extermination of the Protestant heretics.[41]

John Tewkesbury was a London leather seller found guilty by Bishop of London John Stokesley[45] of harbouring English translated New Testaments; he was sentenced to burning for refusing to recant. More declared: he "burned as there was neuer wretche I wene better worthy."[46] After Richard Bayfield was also executed for distributing Tyndale's Bibles, More commented that he was "well and worthely burned".[47]

Modern commentators are divided over More's religious actions as Chancellor. Some biographers, including Ackroyd, have taken a relatively tolerant view of More's campaign against Protestantism by placing his actions within the turbulent religious climate of the time and the threat of deadly catastrophes such as the German Peasants' Revolt, which More blamed on Luther,[48][49][50] as did many others, such as Erasmus.[51] Others have been more critical, such as Richard Marius, an American scholar of the Reformation, believing that such persecutions were a betrayal of More's earlier humanist convictions, including More's zealous and well-documented advocacy of extermination for Protestants.[42]:386–406

Some Protestants take a different view. In 1980, More was added to the Church of England's calendar of Saints and Heroes of the Christian Church, despite being a fierce opponent of the English Reformation that created the Church of England. He was added jointly with John Fisher, to be commemorated every 6 July (the date of More's execution) as "Thomas More, scholar, and John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, Reformation Martyrs, 1535".[12] Pope John Paul II honoured him by making him patron saint of statesmen and politicians in October 2000, stating: "It can be said that he demonstrated in a singular way the value of a moral conscience ... even if, in his actions against heretics, he reflected the limits of the culture of his time".[11]

Resignation

As the conflict over supremacy between the Papacy and the King reached its apogee, More continued to remain steadfast in supporting the supremacy of the Pope as Successor of Peter over that of the King of England. Parliament's reinstatement of the charge of praemunire in 1529 had made it a crime to support in public or office the claim of any authority outside the realm (such as the Papacy) to have a legal jurisdiction superior to the King's.[52]

In 1530, More refused to sign a letter by the leading English churchmen and aristocrats asking Pope Clement VII to annul Henry's marriage to Catherine of Aragon, and also quarrelled with Henry VIII over the heresy laws. In 1531, a royal decree required the clergy to take an oath acknowledging the King as Supreme Head of the Church of England. The bishops at the Convocation of Canterbury in 1532 agreed to sign the Oath but only under threat of praemunire and only after these words were added: "as far as Christ law allows". This was considered to be the final Submission of the Clergy.[53] Cardinal John Fisher and some other clergy refused to sign. Henry purged most clergy who supported the papal stance from senior positions in the church. More continued to refuse to sign the Oath of Supremacy and did not agree to support the annulment of Henry's marriage to Catherine.[52] However, he did not openly reject the King's actions and kept his opinions private.[54]

On 16 May 1532, More resigned from his role as Chancellor but remained in Henry's favour despite his refusal.[55] His decision to resign was caused by the decision of the convocation of the English Church, which was under intense royal threat, on the day before.[56]

Indictment, trial and execution

In 1533, More refused to attend the coronation of Anne Boleyn as the Queen of England. Technically, this was not an act of treason, as More had written to Henry seemingly acknowledging Anne's queenship and expressing his desire for the King's happiness and the new Queen's health.[57] Despite this, his refusal to attend was widely interpreted as a snub against Anne, and Henry took action against him.

Shortly thereafter, More was charged with accepting bribes, but the charges had to be dismissed for lack of any evidence. In early 1534, More was accused by Thomas Cromwell of having given advice and counsel to the "Holy Maid of Kent," Elizabeth Barton, a nun who had prophesied that the king had ruined his soul and would come to a quick end for having divorced Queen Catherine. This was a month after Barton had confessed, which was possibly done under royal pressure,[58][59] and was said to be concealment of treason.[60]

Though it was dangerous for anyone to have anything to do with Barton, More had indeed met with her, and was impressed by her fervour. But More was prudent and told her not to interfere with state matters. More was called before a committee of the Privy Council to answer these charges of treason, and after his respectful answers the matter seemed to have been dropped.[61]

On 13 April 1534, More was asked to appear before a commission and swear his allegiance to the parliamentary Act of Succession. More accepted Parliament's right to declare Anne Boleyn the legitimate Queen of England, though he refused "the spiritual validity of the king's second marriage",[62] and, holding fast to the teaching of papal supremacy, he steadfastly refused to take the oath of supremacy of the Crown in the relationship between the kingdom and the church in England. More furthermore publicly refused to uphold Henry's annulment from Catherine. John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, refused the oath along with More. The oath reads:[63]

...By reason whereof the Bishop of Rome and See Apostolic, contrary to the great and inviolable grants of jurisdictions given by God immediately to emperors, kings and princes in succession to their heirs, hath presumed in times past to invest who should please them to inherit in other men's kingdoms and dominions, which thing we your most humble subjects, both spiritual and temporal, do most abhor and detest...

In addition to refusing to support the King's annulment or supremacy, More refused to sign the 1534 Oath of Succession confirming Anne's role as queen and the rights of their children to succession. More's fate was sealed.[64][65] While he had no argument with the basic concept of succession as stated in the Act, the preamble of the Oath repudiated the authority of the Pope.[54][66][67]

His enemies had enough evidence to have the King arrest him on treason. Four days later, Henry had More imprisoned in the Tower of London. There More prepared a devotional Dialogue of Comfort against Tribulation. While More was imprisoned in the Tower, Thomas Cromwell made several visits, urging More to take the oath, which he continued to refuse.

The charges of high treason related to More's violating the statutes as to the King's supremacy (malicious silence) and conspiring with Bishop John Fisher in this respect (malicious conspiracy) and, according to some sources, for asserting that Parliament did not have the right to proclaim the King's Supremacy over the English Church. One group of scholars believes that the judges dismissed the first two charges (malicious acts) and tried More only on the final one but others strongly disagree.[52]

Regardless of the specific charges, the indictment related to violation of the Treasons Act 1534 which declared it treason to speak against the King's Supremacy:[68]

If any person or persons, after the first day of February next coming, do maliciously wish, will or desire, by words or writing, or by craft imagine, invent, practise, or attempt any bodily harm to be done or committed to the king's most royal person, the queen's, or their heirs apparent, or to deprive them or any of them of their dignity, title, or name of their royal estates … That then every such person and persons so offending … shall have and suffer such pains of death and other penalties, as is limited and accustomed in cases of high treason.[69]

The trial was held on 1 July 1535, before a panel of judges that included the new Lord Chancellor, Sir Thomas Audley, as well as Anne Boleyn's father, brother, and uncle.

More, relying upon legal precedent and the maxim "qui tacet consentire videtur" ("one who keeps silent seems to consent"[70]), understood that he could not be convicted as long as he did not explicitly deny that the King was Supreme Head of the Church, and he therefore refused to answer all questions regarding his opinions on the subject.[71]

Thomas Cromwell, at the time the most powerful of the King's advisors, brought forth Solicitor General Richard Rich to testify that More had, in his presence, denied that the King was the legitimate head of the Church. This testimony was characterised by More as being extremely dubious. Witnesses Richard Southwell and Mr. Palmer both denied having heard the details of the reported conversation, and as More himself pointed out:

Can it therefore seem likely to your Lordships, that I should in so weighty an Affair as this, act so unadvisedly, as to trust Mr. Rich, a Man I had always so mean an Opinion of, in reference to his Truth and Honesty, … that I should only impart to Mr. Rich the Secrets of my Conscience in respect to the King's Supremacy, the particular Secrets, and only Point about which I have been so long pressed to explain my self? which I never did, nor never would reveal; when the Act was once made, either to the King himself, or any of his Privy Councillors, as is well known to your Honours, who have been sent upon no other account at several times by his Majesty to me in the Tower. I refer it to your Judgments, my Lords, whether this can seem credible to any of your Lordships.[72]

_(14785678593).jpg)

The jury took only fifteen minutes, however, to find More guilty.

After the jury's verdict was delivered and before his sentencing, More spoke freely of his belief that "no temporal man may be the head of the spirituality" (take over the role of the Pope). According to William Roper's account, More was pleading that the Statute of Supremacy was contrary to the Magna Carta, to Church laws and to the laws of England, attempting to void the entire indictment against him.[52] He was sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and quartered (the usual punishment for traitors who were not the nobility), but the King commuted this to execution by decapitation.[73]

The execution took place on 6 July 1535. When he came to mount the steps to the scaffold, its frame seeming so weak that it might collapse,[74][75] More is widely quoted as saying (to one of the officials): "I pray you, master Lieutenant, see me safe up and [for] my coming down, let me shift for my self";[76] while on the scaffold he declared that he died "the king's good servant, and God's first."[77][78][79][80] After More had finished reciting the Miserere[81][82] while kneeling, the executioner reportedly begged his pardon, then More rose up merrily, kissed him and gave him forgiveness.[83][84][85][86]

Relics

.jpg)

Another comment he is believed to have made to the executioner is that his beard was completely innocent of any crime, and did not deserve the axe; he then positioned his beard so that it would not be harmed.[87] More asked that his foster/adopted daughter Margaret Clement (née Giggs) be given his headless corpse to bury.[88] She was the only member of his family to witness his execution. He was buried at the Tower of London, in the chapel of St Peter ad Vincula in an unmarked grave. His head was fixed upon a pike over London Bridge for a month, according to the normal custom for traitors.

More's daughter Margaret later rescued the severed head.[89] It is believed to rest in the Roper Vault of St Dunstan's Church, Canterbury,[90] perhaps with the remains of Margaret and her husband's family.[91] Some have claimed that the head is buried within the tomb erected for More in Chelsea Old Church.[92]

Among other surviving relics is his hair shirt, presented for safe keeping by Margaret Clement.[93] This was long in the custody of the community of Augustinian canonesses who until 1983 lived at the convent at Abbotskerswell Priory, Devon. Some sources, including one from 2004, claimed that the hair shirt was then at the Martyr's church on the Weld family's estate in Chideock, Dorset.[94][95] The most recent reports indicate that it is now preserved at Buckfast Abbey, near Buckfastleigh in Devon.[96]

Scholarly and literary work

History of King Richard III

Between 1512 and 1519 More worked on a History of King Richard III, which he never finished but which was published after his death. The History is a Renaissance biography, remarkable more for its literary skill and adherence to classical precepts than for its historical accuracy.[97] Some consider it an attack on royal tyranny, rather than on Richard III himself or the House of York.[98] More uses a more dramatic writing style than had been typical in medieval chronicles; Richard III is limned as an outstanding, archetypal tyrant—however, More was only seven years old when Richard III was killed at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485 so he had no first-hand, in-depth knowledge of him.

The History of King Richard III was written and published in both English and Latin, each written separately, and with information deleted from the Latin edition to suit a European readership.[99] It greatly influenced William Shakespeare's play Richard III. Contemporary historians attribute the unflattering portraits of Richard III in both works to both authors' allegiance to the reigning Tudor dynasty that wrested the throne from Richard III in the Wars of the Roses. More's version barely mentions King Henry VII, the first Tudor king, perhaps because he had persecuted his father, Sir John More. Clements Markham suggests that the actual author of the work was Archbishop Morton and that More was simply copying or perhaps translating the work.[100][101]

Utopia

More's best known and most controversial work, Utopia, is a frame narrative written in Latin.[102] More completed and theologian Erasmus published the book in Leuven in 1516, but it was only translated into English and published in his native land in 1551 (16 years after his execution), and the 1684 translation became the most commonly cited. More (also a character in the book) and the narrator/traveller, Raphael Hythlodaeus (whose name alludes both to the healer archangel Raphael, and 'speaker of nonsense', the surname's Greek meaning), discuss modern ills in Antwerp, as well as describe the political arrangements of the imaginary island country of Utopia (a Greek pun on 'ou-topos' [no place] and 'eu-topos' [good place]) among themselves as well as to Pieter Gillis and Hieronymus van Busleyden. Utopia's original edition included a symmetrical "Utopian alphabet" omitted by later editions, but which may have been an early attempt or precursor of shorthand.

Utopia contrasts the contentious social life of European states with the perfectly orderly, reasonable social arrangements of Utopia and its environs (Tallstoria, Nolandia, and Aircastle). In Utopia, there are no lawyers because of the laws' simplicity and because social gatherings are in public view (encouraging participants to behave well), communal ownership supplants private property, men and women are educated alike, and there is almost complete religious toleration (except for atheists, who are allowed but despised). More may have used monastic communalism as his model, although other concepts he presents such as legalising euthanasia remain far outside Church doctrine. Hythlodaeus asserts that a man who refuses to believe in a god or an afterlife could never be trusted, because he would not acknowledge any authority or principle outside himself. Some take the novel's principal message to be the social need for order and discipline rather than liberty. Ironically, Hythlodaeus, who believes philosophers should not get involved in politics, addresses More's ultimate conflict between his humanistic beliefs and courtly duties as the King's servant, pointing out that one day those morals will come into conflict with the political reality.

Utopia gave rise to a literary genre, Utopian and dystopian fiction, which features ideal societies or perfect cities, or their opposite. Early works influenced by Utopia included New Atlantis by Francis Bacon, Erewhon by Samuel Butler, and Candide by Voltaire. Although Utopianism combined classical concepts of perfect societies (Plato and Aristotle) with Roman rhetorical finesse (cf. Cicero, Quintilian, epideictic oratory), the Renaissance genre continued into the Age of Enlightenment and survives in modern science fiction.

Religious polemics

In 1520 the reformer Martin Luther published three works in quick succession: An Appeal to the Christian Nobility of the German Nation (Aug.), Concerning the Babylonish Captivity of the Church (Oct.), and On the Liberty of a Christian Man (Nov.).[21]:225 In these books, Luther set out his doctrine of salvation through grace alone, rejected certain Catholic practices, and attacked abuses and excesses within the Catholic Church.[21]:225–6 In 1521, Henry VIII formally responded to Luther's criticisms with the Assertio, written with More's assistance. Pope Leo X rewarded the English king with the title "Fidei defensor" ("Defender of the Faith") for his work combating Luther's heresies.[21]:226–7

Martin Luther then attacked Henry VIII in print, calling him a "pig, dolt, and liar".[21]:227 At the king's request, More composed a rebuttal: the Responsio ad Lutherum was published at the end of 1523. In the Responsio, More defended papal supremacy, the sacraments, and other Church traditions. More, though considered "a much steadier personality",[103] described Luther as an "ape", a "drunkard", and a "lousy little friar" amongst other epithets.[21]:230 Writing under the pseudonym of Gulielmus Rosseus,[32] More tells Luther that:

- for as long as your reverend paternity will be determined to tell these shameless lies, others will be permitted, on behalf of his English majesty, to throw back into your paternity's shitty mouth, truly the shit-pool of all shit, all the muck and shit which your damnable rottenness has vomited up, and to empty out all the sewers and privies onto your crown divested of the dignity of the priestly crown, against which no less than the kingly crown you have determined to play the buffoon.[104]

His saying is followed with a kind of apology to his readers, while Luther possibly never apologized for his sayings.[104] Stephen Greenblatt argues, "More speaks for his ruler and in his opponent's idiom; Luther speaks for himself, and his scatological imagery far exceeds in quantity, intensity, and inventiveness anything that More could muster. If for More scatology normally expresses a communal disapproval, for Luther, it expresses a deep personal rage."[105]

Confronting Luther confirmed More's theological conservatism. He thereafter avoided any hint of criticism of Church authority.[21]:230 In 1528, More published another religious polemic, A Dialogue Concerning Heresies, that asserted the Catholic Church was the one true church, established by Christ and the Apostles, and affirmed the validity of its authority, traditions and practices.[21]:279–81 In 1529, the circulation of Simon Fish's Supplication for the Beggars prompted More to respond with The Supplication of Souls.

In 1531, a year after More's father died, William Tyndale published An Answer unto Sir Thomas More's Dialogue in response to More's Dialogue Concerning Heresies. More responded with a half million words: the Confutation of Tyndale's Answer. The Confutation is an imaginary dialogue between More and Tyndale, with More addressing each of Tyndale's criticisms of Catholic rites and doctrines.[21]:307–9 More, who valued structure, tradition and order in society as safeguards against tyranny and error, vehemently believed that Lutheranism and the Protestant Reformation in general were dangerous, not only to the Catholic faith but to the stability of society as a whole.[21]:307–9

Correspondence

Most major humanists were prolific letter writers, and Thomas More was no exception. As in the case of his friend Erasmus of Rotterdam, however, only a small portion of his correspondence (about 280 letters) survived. These include everything from personal letters to official government correspondence (mostly in English), letters to fellow humanist scholars (in Latin), several epistolary tracts, verse epistles, prefatory letters (some fictional) to several of More's own works, letters to More's children and their tutors (in Latin), and the so-called "prison-letters" (in English) which he exchanged with his oldest daughter Margaret while he was imprisoned in the Tower of London awaiting execution.[33] More also engaged in controversies, most notably with the French poet Germain de Brie, which culminated in the publication of de Brie's Antimorus (1519). Erasmus intervened, however, and ended the dispute.[37]

More also wrote about more spiritual matters. They include: A Treatise on the Passion (a.k.a. Treatise on the Passion of Christ), A Treatise to Receive the Blessed Body (a.k.a. Holy Body Treaty), and De Tristitia Christi (a.k.a. The Agony of Christ). More handwrote the last in the Tower of London while awaiting his execution. This last manuscript, saved from the confiscation decreed by Henry VIII, passed by the will of his daughter Margaret to Spanish hands through Fray Pedro de Soto, confessor of Emperor Charles V. More's friend Luis Vives received it in Valencia, where it remains in the collection of Real Colegio Seminario del Corpus Christi museum.

Canonization

Catholic Church

Pope Leo XIII beatified Thomas More, John Fisher, and 52 other English Martyrs on 29 December 1886. Pope Pius XI canonised More and Fisher on 19 May 1935, and More's feast day was established as 9 July.[106] Since 1970 the General Roman Calendar has celebrated More with St John Fisher on 22 June (the date of Fisher's execution). On 31 October 2000 Pope John Paul II declared More "the heavenly Patron of Statesmen and Politicians".[11] More is the patron of the German Catholic youth organisation Katholische Junge Gemeinde.[107]

Anglican Communion

In 1980, despite their opposing the English Reformation, More and Fisher were added as martyrs of the reformation to the Church of England's calendar of "Saints and Heroes of the Christian Church", to be commemorated every 6 July (the date of More's execution) as "Thomas More, scholar, and John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, Reformation Martyrs, 1535".[12]

Legacy

The steadfastness and courage with which More maintained his religious convictions, and his dignity during his imprisonment, trial, and execution, contributed much to More's posthumous reputation, particularly among Roman Catholics. His friend Erasmus defended More's character as "more pure than any snow" and described his genius as "such as England never had and never again will have."[108] Upon learning of More's execution, Emperor Charles V said: "Had we been master of such a servant, we would rather have lost the best city of our dominions than such a worthy councillor."[109] G. K. Chesterton, a Roman Catholic convert from the Church of England, predicted More "may come to be counted the greatest Englishman, or at least the greatest historical character in English history."[110] Hugh Trevor-Roper called More "the first great Englishman whom we feel that we know, the most saintly of humanists, the most human of saints, the universal man of our cool northern renaissance."[111]

Jonathan Swift, an Anglican, wrote that More was "a person of the greatest virtue this kingdom ever produced".[112][113][114] Some consider Samuel Johnson that quote's author, although neither his writings nor Boswell's contain such.[115][116] The metaphysical poet John Donne, also honoured as a saint by Anglicans, was More's great-great-nephew.[117] US Senator Eugene McCarthy had a portrait of More in his office.[118]

Roman Catholic scholars maintain that More used irony in Utopia, and that he remained an orthodox Christian.

Marxist theoreticians such as Karl Kautsky considered the book a critique of economic and social exploitation in pre-modern Europe and More is claimed to have influenced the development of socialist ideas.[119]

Communism, socialism and resistance to communism

Having been praised "as a Communist hero by Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, and Karl Kautsky" because of the Communist attitude to property in his Utopia,[13] under Soviet Communism the name of Thomas More was in ninth position from the top[14] of Moscow's Stele of Freedom (also known as the Obelisk of Revolutionary Thinkers),[15] as one of the most influential thinkers "who promoted the liberation of humankind from oppression, arbitrariness, and exploitation."[14] This monument was erected in 1918 in Aleksandrovsky Garden near the Kremlin at Lenin's suggestion.[13][120][14][15] It was dismantled on 2 July 2013, during Vladimir Putin's third term as President of post-Communist Russia.[15]

Utopia also inspired socialists such as William Morris.[121]

Many see More's communism or socialism as purely satirical.[121] In 1888, while praising More's communism, Karl Kautsky pointed out that "perplexed" historians and economists often saw the name Utopia (which means "no place") as "a subtle hint by More that he himself regarded his communism as an impracticable dream".[119]

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, the Russian Nobel Prize-winning, anti-Communist author of The Gulag Archipelago, argued that Soviet communism needed enslavement and forced labour to survive, and that this had been " ...foreseen as far back as Thomas More, in his Utopia".[122]

In 2008, More was portrayed on stage in Hong Kong as an allegorical symbol of the pan-democracy camp resisting the Chinese Communist Party in a translated and modified version of Robert Bolt's play A Man for All Seasons.[123]

Literature and popular culture

William Roper's biography of More was one of the first biographies in Modern English.

Sir Thomas More is a play written circa 1592 in collaboration with Henry Chettle, Anthony Munday, William Shakespeare, and others. In it More is portrayed as a wise and honest statesman. The original manuscript has survived as a handwritten text that shows many revisions by its several authors, as well as the censorious influence of Edmund Tylney, Master of the Revels in the government of Queen Elizabeth I. The script has since been published and has had several productions.[124][125]

The 20th-century agnostic playwright Robert Bolt portrayed Thomas More as the tragic hero of his 1960 play A Man for All Seasons. The title is drawn from what Robert Whittington in 1520 wrote of More:

More is a man of an angel's wit and singular learning. I know not his fellow. For where is the man of that gentleness, lowliness and affability? And, as time requireth, a man of marvelous mirth and pastimes, and sometime of as sad gravity. A man for all seasons.[111]

In 1966, the play A Man for All Seasons was adapted into a film with the same title. It was directed by Fred Zinnemann and adapted for the screen by the playwright. It stars Paul Scofield, a noted British actor, who said that the part of Sir Thomas More was "the most difficult part I played."[126] The film won the Academy Award for Best Picture and Scofield won the Best Actor Oscar. In 1988 Charlton Heston starred in and directed a made-for-television film that restored the character of "the common man" that had been cut from the 1966 film.

In the 1969 film Anne of the Thousand Days, More is portrayed by actor William Squire.

Catholic science fiction writer R. A. Lafferty wrote his novel Past Master as a modern equivalent to More's Utopia, which he saw as a satire. In this novel, Thomas More travels through time to the year 2535, where he is made king of the world "Astrobe", only to be beheaded after ruling for a mere nine days. One character compares More favourably to almost every other major historical figure: "He had one completely honest moment right at the end. I cannot think of anyone else who ever had one."

Karl Zuchardt's novel, Stirb du Narr! ("Die you fool!"), about More's struggle with King Henry, portrays More as an idealist bound to fail in the power struggle with a ruthless ruler and an unjust world.

The novelist Hilary Mantel portrays More as an unsympathetic persecutor of Protestants, and an ally of the Habsburg empire, in her 2009 novel Wolf Hall, told from the perspective of a sympathetically portrayed Thomas Cromwell.

Literary critic James Wood in his book The Broken Estate, a collection of essays, is critical of More and refers to him as "cruel in punishment, evasive in argument, lusty for power, and repressive in politics".[127]

Aaron Zelman's non-fiction book The State Versus the People includes a comparison of Utopia with Plato's Republic. Zelman is undecided as to whether More was being ironic in his book or was genuinely advocating a police state. Zelman comments, "More is the only Christian saint to be honoured with a statue at the Kremlin." By this Zelman implies that Utopia influenced Vladimir Lenin's Bolsheviks, despite their brutal repression of religion.

Other biographers, such as Peter Ackroyd, have offered a more sympathetic picture of More as both a sophisticated philosopher and man of letters, as well as a zealous Catholic who believed in the authority of the Holy See over Christendom.

The protagonist of Walker Percy's novels, Love in the Ruins and The Thanatos Syndrome, is "Dr Thomas More", a reluctant Catholic and descendant of More.

More is the focus of the Al Stewart song "A Man For All Seasons" from the 1978 album Time Passages, and of the Far song "Sir", featured on the limited editions and 2008 re-release of their 1994 album Quick. In addition, the song "So Says I" by indie rock outfit The Shins alludes to the socialist interpretation of More's Utopia.

Jeremy Northam depicts More in the television series The Tudors as a peaceful man, as well as a devout Roman Catholic and loving family patriarch. He also shows More loathing Protestantism, burning both Martin Luther's books and English Protestants who have been convicted of heresy. The portrayal has unhistorical aspects, such as that More neither personally caused nor attended Simon Fish's execution (since Fish actually died of bubonic plague in 1531 before he could stand trial), although More's The Supplycatyon of Soulys, published in October 1529, addressed Fish's Supplication for the Beggars.[128][129] Indeed, there is no evidence that More ever attended the execution of any heretic. The series also neglected to show More's avowed insistence that Richard Rich's testimony about More disputing the King's title as Supreme Head of the Church of England was perjured.

In 2002, More was placed at number 37 in the BBC's poll of the 100 Greatest Britons.[130]

Institutions named after More

Historic sites

Westminster Hall

A plaque in the middle of the floor of London's Westminster Hall commemorates More's trial for treason and condemnation to execution in that original part of the Palace of Westminster.[131] The building, which houses Parliament, would have been well known to More, who served several terms as a member and became Speaker of the House of Commons before his appointment as England's Lord Chancellor.

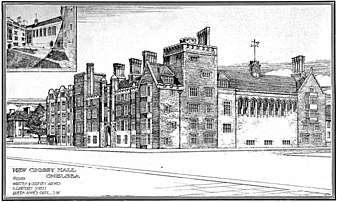

Crosby Hall

After his execution The Crown confiscated Crosby Hall, More's home in Bishopsgate in The City of London, and his estate along the Thames in Chelsea. Parts of the house survived until demolished in 1909 when some elements, including the hammer-beam roof of the Great Hall, part of a musicians' gallery, a postern doorway and some oriel windows, were placed in storage and eventually incorporated into a new building erected at the site of More's estate in Chelsea.[132][133] It is privately owned and closed to the public.

Chelsea Old Church

Across a small park and Old Church Street from Crosby Hall is Chelsea Old Church, an Anglican church whose southern chapel More commissioned and in which he sang with the parish choir. Except for his chapel, the church was largely destroyed in the Second World War and rebuilt in 1958. The capitals on the medieval arch connecting the chapel to the main sanctuary display symbols associated with More and his office. On the southern wall of the sanctuary is the tomb and epitaph he erected for himself and his wives, detailing his ancestry and accomplishments in Latin, including his role as peacemaker between the various Christian European states as well as a curiously altered portion about his curbing heresy. When More served Mass, he would leave by the door just to the left of it. He is not, however, buried here, nor is it entirely certain which of his family may be. It is open to the public at specific times. Outside the church, facing the River Thames, is a statue by L. Cubitt Bevis erected in 1969, commemorating More as "saint", "scholar", and "statesman"; the back displays his coat-of-arms. Nearby, on Upper Cheyne Row, the Roman Catholic Church of Our Most Holy Redeemer & St. Thomas More honours the martyr.

Tower Hill

A plaque and small garden commemorate the famed execution site on Tower Hill, London, just outside the Tower of London, as well as all those executed there, many as religious martyrs or as prisoners of conscience. More's corpse, minus his head, was unceremoniously buried in an unmarked mass grave beneath the Royal Chapel of St. Peter Ad Vincula, within the walls of the Tower of London, as was the custom for traitors executed at Tower Hill. The chapel is accessible to Tower visitors.

St Katharine Docks

Thomas More is commemorated by a stone plaque near St Katharine Docks, just east of the Tower where he was executed. The street in which it is situated was formerly called Nightingale Lane, a corruption of "Knighten Guild", derived from the original owners of the land. It is now renamed Thomas More Street in his honour.[134]

St Dunstan's Church and Roper House, Canterbury

St Dunstan's Church, an Anglican parish church in Canterbury, possesses More's head, rescued by his daughter Margaret Roper, whose family lived in Canterbury down and across the street from their parish church. A stone immediately to the left of the altar marks the sealed Roper family vault beneath the Nicholas Chapel, itself to the right of the church's sanctuary or main altar. St Dunstan's Church has carefully investigated, preserved and sealed this burial vault. The last archaeological investigation revealed that the suspected head of More rests in a niche separate from the other bodies, possibly from later interference.[135] Displays in the chapel record the archaeological findings in pictures and narratives. Roman Catholics donated stained glass to commemorate the events in More's life. A small plaque marks the former home of William and Margaret Roper; another house nearby and entitled Roper House is now a home for the deaf.

Works

Note: The reference "CW" is to the relevant volume of the Yale Edition of the Complete Works of St. Thomas More (New Haven and London 1963–1997)

Published during More's life (with dates of publication)

- A Merry Jest (c. 1516) (CW 1)

- Utopia (1516) (CW 4)

- Latin Poems (1518, 1520) (CW 3, Pt.2)

- Letter to Brixius (1520) (CW 3, Pt. 2, App C)

- Responsio ad Lutherum (The Answer to Luther, 1523) (CW 5)

- A Dialogue Concerning Heresies (1529, 1530) (CW 6)

- Supplication of Souls (1529) (CW 7)

- Letter Against Frith (1532) (CW 7) pdf

- The Confutation of Tyndale's Answer (1532, 1533) (CW 8) Books 1–4, Books 5–9

- Apology (1533) (CW 9)

- Debellation of Salem and Bizance (1533) (CW 10) pdf

- The Answer to a Poisoned Book (1533) (CW 11) pdf

Published after More's death (with likely dates of composition)

- The History of King Richard III (c. 1513–1518) (CW 2 & 15)

- The Four Last Things (c. 1522) (CW 1)

- A Dialogue of Comfort Against Tribulation (1534) (CW 12)

- Treatise Upon the Passion (1534) (CW 13)

- Treatise on the Blessed Body (1535) (CW 13)

- Instructions and Prayers (1535) (CW 13)

- De Tristitia Christi (1535) (CW 14) (preserved in the Real Colegio Seminario del Corpus Christi, Valencia)

Translations

- Translations of Lucian (many dates 1506–1534) (CW 3, Pt.1)

- The Life of Pico della Mirandola, by Gianfrancesco Pico della Mirandola (c. 1510) (CW 1)

Notes

- Topic 1.3: The Northern Renaissance

- Plato's Dialectical Politics and Thomas More's Utopia

- AUGUSTINE’S AND MORE’S USE OF CICERO

- How Utopia shaped the world

- Is Thomas More's 'Utopia'

- The Life of St. Thomas More

- "St. Thomas More". savior.org. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- Homily at the Canonization of St. Thomas More at The Center for Thomas More Studies at the University of Dallas, 2010, citing text "Recorded in The Tablet, June 1, 1935, pp. 694–695"

- Linder, Douglas O. The Trial of Sir Thomas More: A Chronology at University Of Missouri-Kansas City (UMKC) School Of Law

- Jubilee of parliament and government members, proclamation of Saint Thomas More as patron of statesmen vatican.va

- Apostolic letter issued motu proprio proclaiming Saint Thomas More Patron of Statesmen and Politicians, 31 October 2000 Vatican.va

- "Holy Days". Worship – The Calendar. Church of England. 2011. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- King, Margaret L. (2014). Renaissance Humanism: An Anthology of Sources. Hackett Publishing. p. 157. ISBN 978-1-62466-146-4.

- "The Center for Thomas More Studies Art > Gallery > Moscow". The Center for Thomas More Studies at The University of Dallas. 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

This monument, suggested by Lenin and built in 1918, lists Thomas More (ninth from the top) among the most influential thinkers "who promoted the liberation of humankind from oppression, arbitrariness, and exploitation." It is in Aleksndrovsky Garden near the Kremlin.

- afoniya (10 July 2013). "On the removal of a Moscow statue". Retrieved 20 December 2014.

What was known as the Stele of Freedom or the Obelisk of Revolutionary Thinkers has been dismantled apparently to be reinstalled in some months time as a monument to the Romanov Dynasty. This historically symbolic act was carried out on 2 July completely unannounced … The obelisk was one of the most interesting statues historically and ideologically because of the kind of names that it had on the statue. This was not simply a case of Marx, Engels, Lenin. It was (it seems) the first revolutionary monument to be opened after the revolution of 1917 and, in a non-dogmatic spirit, it included the names of anarchists, reformist socialists and even that of Thomas More.

- Jokinen, A. (13 June 2009). "The Life of Sir Thomas More." Luminarium. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- Glenn, Garrard (1 January 1941). "St. Thomas More As Judge and lawyer". Fordham Law Review. 10 (2): 187.

- "Sir Thomas More". The Biography Channel website. 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- "Thomas More: Always a Londoner". tudortimes.co.uk. 24 September 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- Rebhorn, Wayne A, ed. (2005). "Introduction". Utopia. Classics. New York: Barnes & Noble..

- Ackroyd, Peter (1999). The Life of Thomas More. New York: Anchor Books..

- Harpsfield, Nicholas (1931). "The Life and Death of Sr Thomas More". London: Early English Text Society: 12–3. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help). - Erasmus, Desiderius (1991). "Letter to Ulrich von Hutten". In Adams, Robert M. (ed.). Utopia. New York: WW Norton & Co. p. 125.

- "Erasmus to Ulrich von Hutten" (PDF). The Center for Thomas More Studies. Biographical Accounts: Erasmus' Letters about More. Thomasmorestudies.org. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- "Franciscan Calendar". Tau Cross Region of the Secular Franciscan Order. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013.

- Gerard B. Wegemer (1995). Thomas More: A Portrait of Courage. Scepter Publishing.

- John A. Wagner; Susan Walters Schmid (2011). Encyclopedia of Tudor England. ABC-CLIO. pp. 769–770. ISBN 978-1598842999.

- Maddison, the Rev. Canon, A.R., M.A., F.S.A., editor, Lincolnshire Pedigrees, Harleian Society, London, 1903, p.5.

- More, St Thomas (1961). Rogers, Elizabeth Frances (ed.). Selected Letters. New Haven and London: Yale University Press..

- "History of Parliament". History of Parliament Trust. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- Magnusson (ed.) Chambers Biographical Dictionary (1990) p. 1039

- Rebhorn, W. A. (ed.) p. xviii

- Gerard B. Wegemer, Portrait of Courage, p. 136.

- MacCulloch, Diarmaid (27 September 2018). Thomas Cromwell : a life. pp. 160–162. ISBN 9781846144295.

- David Loewenstein; Janel Mueller, eds. (2002). The Cambridge History of Early Modern English Literature. Cambridge University Press. p. 93 (footnote 36). ISBN 0521631564.

- Andrew Hiscock; Helen Wilcox, eds. (2017). The Oxford Handbook of Early Modern English Literature and Religion. Oxford University Press. p. 547. ISBN 978-0191653421.

- Moynahan, Brian, God's Bestseller: William Tyndale, Thomas More, and the Writing of the English Bible – A Story of Martyrdom and Betrayal, St Martin's Press; 1st ed. (23 August 2003).

- Diarmaid MacCulloch, 277.

- Farris, Michael (2007). "From Tyndale to Madison". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help). - Peter Ackroyd (2012). The Life of Thomas More. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0307823014.

- Richard Marius (1999). Thomas More: A Biography. Harvard University Press. p. 406. ISBN 0674885252.

- Marius, Richard (1999). Thomas More: A Biography, Harvard University Press

- Moynahan, B., William Tyndale: If God Spare My Life, Abacus, London, 2003.

- Guy, John A. Tudor England Oxford, 1988. p 26

- "John Tewkesbury (1531)". UK Wells. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

Having failed in this the Bishop of London, Stokesley, tried him and sentenced him to be burned.

- More, Thomas (1973). Schuster, LA; Marius, RC; Lusardi, JP; Schoeck, RJ (eds.). The Confutation of Tyndale's Answer. Complete Works. 8. Yale. p. 20..

- Peter Ackroyd (2012). The Life of Thomas More. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0307823014.

- Wegemer, Gerard (1996). Thomas More on statesmanship. Catholic University of America Press. p. 173.

...civil chaos will surely follow (691–93). This prediction seemed to come true very quickly, as More noted in his next polemical work, A dialogue Concerning Heresies. There he argued that the Peasants' Revolt in Germany (1525), the Lutheran mercenaries' sack of Rome (1527), and the growing unrest in England all stemmed from Luther's inflammatory teachings and especially the lure of false freedom

Original from the University of Michigan Digitized 29 Jul 2009 - Peter Ackroyd (1998). The Life of Thomas More. Chatto & Windus. p. 244. ISBN 1-85619-711-5.

(Chapter 22) ... Already, in these early days of English heresy, he was thinking of the fire. It is a measure of his alarm at the erosion of the traditional order that he should, in this letter, compose a defence of scholastic theology—the same scholasticism which in his younger days he had treated with derision. This was no longer a time for questioning, or innovation, or uncertainty, of any kind. He blamed Luther for the Peasants’ Revolt in Germany, and maintained that all its havoc and destruction were the direct result of Luther’s challenge to the authority of the Church; under the pretext of ‘libertas’ Luther preached ‘licentia’ which had in turn led to rape, sacrilege, bloodshed, fire and ruin.

(Online citation here) - Joanne Paul (2016). Thomas More. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780745692203.

Princes were 'driven by necessity' by the 'importune malice of heretics raising rebellions' to set 'sorer and sorer punishments thereunto' (CTA, 956). In other words, the heretics had started it: 'the Catholic Church did never persecute heretics by any temporal pain or any secular power until the heretics began such violence themself' (CTA, 954). More had in mind violent conflicts on the continent, such as the German Peasants' War (1524–5) and the Münster Rebellion (1532–5).

(CTA=Confutation of Tyndale's Answer) - Wegemer, Gerard (31 October 2001). "Thomas More as statesman" (PDF). The Center for Thomas More Studies. p. 8. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

In the Peasants’ Revolt in Germany in 1525, More pointed out, 70,000 German peasants were slaughtered – and More, along with Erasmus and many others, considered Luther to be largely responsible for that wildfire.

- Henry Ansgar Kelly; Louis W. Karlin; Gerard Wegemer, eds. (2011). Thomas More's Trial by Jury: A Procedural and Legal Review with a Collection of Documents. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. pp. xiv–xvi. ISBN 978-1843836292.

- Gerard Wegemer (1995). Thomas More: A Portrait of Courage. Scepter Publishers. p. xiv. ISBN 188933412X.

- Thomas More (2010). Utopia. Translated by G.C. Richards, William P. Weaver. Broadview Press. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-1460402115.

- Daniel Eppley (2016). Defending Royal Supremacy and Discerning God's Will in Tudor England. Routledge. p. 13. ISBN 978-1351945790.

- George M. Logan, ed. (2011). The Cambridge Companion to Thomas More. Cambridge University Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-1139828482.

- Ives, Eric W (2004), The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn, p. 47,

[More wrote on the subject of the Boleyn marriage that] [I] neither murmur at it nor dispute upon it, nor never did nor will. ...I faithfully pray to God for his Grace and hers both long to live and well, and their noble issue too...

- David Knowles (1979). The Religious Orders in England. 3. Cambridge University Press. pp. 188–189. ISBN 0521295688.

- Patricia Crawford (2014). Women and Religion in England: 1500–1720. Routledge. p. 29. ISBN 978-1136097560.

- Peter Ackroyd (2012). The Life of Thomas More. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 342. ISBN 978-0307823014.

- Lee, Sidney (1904). Great Englishmen of the Sixteenth Century. London: Archibald Constable, Limited. p. 48.

- George M. Logan, ed. (2011). The Cambridge Companion to Thomas More. Cambridge University Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-1139828482.

- Elton, Geoffrey Rudolph (1982). "The Crown". The Tudor constitution: documents and commentary (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Cambridgeshire: Cambridge University Press. p. 7. ISBN 0-521-24506-0. OCLC 7876927. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- Gerard Wegemer; Stephen W. Smith, eds. (2004). A Thomas More Source Book. The Catholic University of America Press. p. 305. ISBN 0813213762.

- Lawrence Wilde (2016). Thomas More's Utopia: Arguing for Social Justice. Routledge. pp. 112–113. ISBN 978-1317281375.

- G. R. Elton (1985). Policy and Police: The Enforcement of the Reformation in the Age of Thomas Cromwell. CUP Archive. p. 223. ISBN 0521313090.

- The Twentieth Century, Volume 30, Nineteenth Century and After, 1891, p. 556

- John A. Wagner (2015). Voices of the Reformation: Contemporary Accounts of Daily Life. ABC-CLIO. p. 170. ISBN 978-1610696807.

- "Annotated original text". November 2017.

- Henry Ansgar Kelly; Louis W. Karlin; Gerard Wegemer, eds. (2011). Thomas More's Trial by Jury: A Procedural and Legal Review with a Collection of Documents. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. p. 189. ISBN 978-1843836292.

- Henry Ansgar Kelly; Louis W. Karlin; Gerard Wegemer, eds. (2011). Thomas More's Trial by Jury: A Procedural and Legal Review with a Collection of Documents. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. p. 22. ISBN 978-1843836292.

- "The Trial of Sir THOMAS MORE Knight, Lord Chancellor of England, for High-Treason in denying; the King's Supremacy, May 7, 1535. the 26th of Henry VIII".

- Anne Manning; Edmund Lodge (1852). The Household of Sir Thomas More. C. Scribner. p. xiii.

thomas more sentenced hanged, drawn and quartered.

- MacFarlane, Charles; Thomson, Thomas (1876). The comprehensive history of England, from the earliest period to the suppression of the Sepoy revolt. Blackie and Son. p. 798.

- Bridgett, Thomas Edward (1891). Life and Writings of Sir Thomas More: Lord Chancellor of England and Martyr Under Henry VIII (3 ed.). Burns & Oates. p. 434.

- Elizabeth M. Knowles, ed. (1999). The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations. Oxford University Press. p. 531. ISBN 0198601735.

- "Famous Quotes". The Center for Thomas More Studies at The University of Dallas. Archived from the original on 11 January 2018. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- Gerard Wegemer; Stephen W. Smith, eds. (2004). A Thomas More Source Book. The Catholic University of America Press. p. 357. ISBN 0813213762.

- Scott W. Hahn; David Scott, eds. (2009). Liturgy and Empire: Faith in Exile and Political Theology. Emmaus Road Publishing. p. 73. ISBN 978-1931018562.

I die the king's good servant, but God's first." Footnote 133: "This phrase from Robert Bolt's play 'A Man for All Seasons' ... is an adjustment of More's actual last words: 'I die the king's good servant, and God's first.'

- Shepherd, Rose (2014). "Powerhouse, Treasurehouse, Slaughterhouse". At Home with Henry VIII: His Life, His Wives, His Palaces. London: CICO Books. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-78249-160-6.

- Kerry McCarthy (2008). Liturgy and Contemplation in Byrd's Gradualia. Routledge. p. 61. ISBN 978-1135865641.

- Ecclesiastical Biography, Or, Lives of Eminent Men Connected with the History of Religion in England: From the Commencement of the Reformation to the Revolution, Ecclesiastical Biography, Or, Lives of Eminent Men Connected with the History of Religion in England. 2. London: F.C. and J. Rivington. 1810. pp. 222–223.

- Spencer J. Weinreich, ed. (2017). Pedro de Ribadeneyra's 'Ecclesiastical History of the Schism of the Kingdom of England'. BRILL. p. 238. ISBN 978-9004323964.

- A Collection of the most remarkable Trials of persons for High-Treason, Murder, Heresy ... IV. London: T. Read. 1736. p. 94.

- Agnes M. Stewart (1876). The Life and Letters of Sir Thomas More. Burns & Oates. p. 339.

- W. Jos Walter (1840). Sir Thomas More His Life and Times: Illustrated from His Own Writings and from Contemporary Documents. London: Charles Dolman. p. 353.

- Hume, David (1813), The History of England, p. 632.

- Guy, John, A Daughter's Love: Thomas & Margaret More, London: Fourth Estate, 2008, ISBN 978-0-00-719231-1, p. 266.

- Thomas Edward Bridgett (1891). Life and Writings of Sir Thomas More: Lord Chancellor of England and Martyr Under Henry VIII. Burns & Oates. p. 436.

thomas more head buried.

- "Journal of the British Archaeological Association". 1. British Archaeological Association. 1895: 142–144. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Lady Margaret Roper and the head of Sir Thomas More". Insert Logo Here Lynsted with Kingsdown Society. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- Doyne Courtenay Bell (1877). Notices of the Historic Persons Buried in the Chapel of St. Peter Ad Vincula: In the Tower of London. J. Murray. pp. 88–91.

- "St. Thomas More". Catholic Encyclopaedia..

- David Hilliam (2010). Little Book of Dorset. History Press. ISBN 978-0752462653.

- Anne Vail (2004). Shrines of Our Lady in England. Gracewing Publishing. p. 42. ISBN 0852446039.

- Simon Caldwell (21 November 2016). "St. Thomas More's hair shirt now enshrined for public veneration". Catholic News Service.

- Wegemer, Gerard (1998). Thomas More on Statesmanship (1st ed.). Washington D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press. p. 218. ISBN 0-8132-0913-7.

- Meyer, Jürgen (2014). An Unthinkable History of... Journal Article. The Modern Language Review. pp. 629–639. doi:10.5699/modelangrevi.109.3.0629.

- Logan (2011) p168

- Markham, Clements (1906). Richard III: His Life and Character. p. 168.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Yoran, H. Thomas More's Richard III: Probing the Limits of Humanism. Renaissance Studies 15, no. 4 (2001): 514–37. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- More, Thomas. "Introduction". In Lumby, J Rawson (ed.). More's Utopia. Translated by Robynson, Raphe (1952 ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. vii. ISBN 9781107645158.

- John Vidmar (2005). The Catholic Church Through the Ages: A History. Paulist Press. p. 184. ISBN 0809142341.

- Alan Dundes; Carl R. Pagter (1978). Work Hard and You Shall be Rewarded: Urban Folklore from the Paperwork Empire. Wayne State University Press. pp. 60–61. ISBN 0814324320.

- Stephen Greenblatt (2012). Learning to Curse: Essays in Early Modern Culture. Routledge. p. 95. ISBN 978-1136774201.

- Brown, Brendan F. (1935). "St. Thomas More, lawyer". Fordham Law Review. 3 (3): 375–390.

- "Thomas Morus". kjg.de. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- Daniel J. Boorstin (1999). The Seekers: The Story of Man's Continuing Quest to Understand His World. Random House Digital, Inc. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-375-70475-8.

- Quoted in Britannica – The Online Encyclopedia, article: Sir Thomas More

- Chesterton, G. K. (1929). The Fame of Blessed Thomas More. London: Sheed & Ward. p. 63.

- Cited in Marvin O'Connell, "A Man for all Seasons: an Historian's Demur," Catholic Dossier 8 no. 2 (March–April 2002): 16–19 online

- Jonathan Swift. "Writings on Religion and the Church, Vol. I. by Jonathan Swift: Ch. 14: Concerning that Universal Hatred".

- Jonathan Swift, Prose Works of Jonathan Swift v. 13, Oxford UP, 1959, p. 123)

- "Reputation". Thomas More Studies. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help). - Kenny, Jack (2011). "A Man of Enduring Conscience". Resource Center. Catholic Culture via Trinity Communications.

- Chambers, R. W. (1929). Sir Thomas More's Fame Among His Countrymen. London: Sheed & Ward. p. 13.

- Colclough, David (2011) [2004]. "Donne, John (1572–1631)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/7819. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- McNamara, Robert (2003). "Irish Perspectives on the Vietnam War". Irish Studies in International Affairs. 14: 75–94. doi:10.3318/ISIA.2003.14.1.75. JSTOR 30001965.

- Kautsky, Karl (1888). Thomas More and his Utopia. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

Part III. UTOPIA … Chapter V. THE AIM OF UTOPIA … Historians and economists who are perplexed by Utopia perceive in this name a subtle hint by More that he himself regarded his communism as an impracticable dream.

- Guy, John Alexander (2000). Thomas More. Arnold. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-0-340-73139-0.

- "St. Thomas More". Catholic Encyclopaedia. 1913.

The whole work is really an exercise of the imagination with much brilliant satire upon the world of More's own day. … there can be no doubt that he would have been delighted at entrapping William Morris, who discovered in it a complete gospel of Socialism

- Bloom, Harold; Hobby, Blake (2010). Enslavement and Emancipation. Infobase Publishing. pp. 173–174. ISBN 978-1-60413-441-4. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

Moreover, Solzhenitsyn insists that the Soviet system cannot survive without the camps, that Soviet communism requires enslavement and forced labour. " ...foreseen as far back as Thomas More, in his Utopia [,the] labor of zeks was needed for degrading and particularly heavy work, which no one, under socialism, would wish to perform" (Gulag, Vol 3." 578).

- Chen, Chapman (2011). Pekka Kujamäki (ed.). "Postcolonial Hong Kong Drama Translation" in "Beyond Borders: Translations Moving Languages, Literatures and Cultures". Volume 39 of TransÜD. Arbeiten zur Theorie und Praxis des Übersetzens und Dolmetschens. Frank & Timme GmbH, Berlin. pp. 47–54. ISBN 978-3-86596-356-7. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- Long, William B. The Occasion of the Book of Sir Thomas More. Howard-Hill, T.H. editor. Shakespeare and Sir Thomas More; essays on the play and its Shakespearean Interest. Cambridge University Press. (1989) ISBN 0 521 34658 4. pages 49–54

- Gabrieli, Vittorio. Melchiori, Giorgio, editors Introduction. Munday, Anthony. And others. Sir Thomas More. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-1544-8. Page 1

- Gary O'Connor (2002), Paul Scofield: An Actor for All Seasons, Applause Books. Page 150.

- Wood, James (2010). The Broken Estate: Essays on Literature and Belief. New York: Picador. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-312-42956-0.

- Fish, Simon (1871). A Supplicacyon for the Beggers. Early English Text Society.

simon fish.

- see Fish, Simon. "Supplycacion for the Beggar." 1529 in Carroll, Gerald L. and Joseph B. Murray. The Yale Edition of the Complete Works of St. Thomas More. Vol. 7. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990, pp. 1–10. See also Pineas, Rainer. "Thomas More's Controversy with Simon Fish." Studies in English Literature, 1500–1900, Vol. 7, No. 1, The English Renaissance, Winter, 1967, 13–14.

- Sue Parrill, William Baxter Robison (2013). "The Tudors on Film and Television", p. 92. McFarland,

- "Westminster Hall". The Center for Thomas More Studies. 2010. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- "Crosby Hall". The Times (39282). London. 26 May 1910. p. 8.

- Weinreb, Ben; Hibbert, Christopher (1983). "Crosby Hall". The London Encyclopaedia (1995 ed.). pp. 219–220. ISBN 0-333-57688-8.

- "St Katharine's Dock". Exploring East London. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- Schulte Herbrüggen, Hubertus (1982). Das Haupt des Thomas Morus in der St. Dunstan-Kirche zu Canterbury. Forschungsberichte des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Biographies

- Ackroyd, Peter (1999). The Life of Thomas More.

- Basset, Bernard, SJ (1965). Born for Friendship: The Spirit of Sir Thomas More. London: Burns & Oates.

- Berglar, Peter (2009). Thomas More: A Lonely Voice against the Power of the State. New York: Scepter Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59417-073-7. (Note: this is a 2009 translation (from the original German, by Hector de Cavilla) of Berglar's 1978 work Die Stunde des Thomas Morus – Einer gegen die Macht. Freiburg 1978; Adamas-Verlag, Köln 1998, ISBN 3-925746-78-1)

- Brady, Charles A. (1953). Stage of Fools: A Novel of Sir Thomas More. Dutton.

- Brémond, Henri (1904) – Le Bienheureux Thomas More 1478–1535 (1904) as Sir Thomas More (1913) translated by Henry Child;

- 1920 edition published by R. & T. Washbourne Limited, OCLC 1224822, 749455885;

- Paperback edition by Kessinger Publishing, LLC (26 May 2006) with ISBN 1-4286-1904-6, ISBN 978-1-4286-1904-3;

- published in French in Paris by Gabalda, 1920, OCLC 369064822

- (Note: Brémond is frequently cited in Berglar (2009))

- Bridgett, Thomas Edward (1891). Life and Writings of Sir Thomas More, Lord Chancellor of England and Martyr under Henry VIII.

- Chambers, RW (1935). Thomas More. Harcourt, Brace.

- Guy, John (1980). The Public Career of Sir Thomas More. ISBN 978-0-300-02546-0.

- ——— (2000). Thomas More. ISBN 978-0-340-73138-3.

- ——— (2009). A Daughter's Love: Thomas More and His Daughter Meg.

- House, Seymour B. (2008) [2004]. "More, Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/19191. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Marius, Richard (1984). Thomas More: A Biography. Vintage Books.

- ——— (1999). Thomas More: a biography. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-88525-7.

- More, Cresacre (1828). The Life of Sir Thomas More by His Great-Grandson. W. Pickering. p. 344..

- Phélippeau, Marie-Claire (2016). Thomas More. Gallimard.

- Reynolds, EE (1964). The Trialet of St Thomas More.

- ——— (1965). Thomas More and Erasmus. New York, Fordham University Press.

- Ridley, Jasper (1983). Statesman and Saint: Cardinal Wolsey, Sir Thomas More, and the Politics of Henry VIII. ISBN 0-670-48905-0.

- Roper, William (2003), Wegemer, Gerard B; Smith, Stephen W (eds.), The Life of Sir Thomas More (1556) (PDF), Center for Thomas More Studies.

- Stapleton, Thomas, The Life and Illustrious Martyrdom of Sir Thomas More (1588) (PDF).

- Wegemer, Gerard (1985). Thomas More: A Portrait of Courage. ISBN 978-1-889334-12-7.

- ——— (1996), Thomas More on Statesmanship.

Historiography

- Gushurst-Moore, André (2004), "A Man for All Eras: Recent Books on Thomas More", Political Science Reviewer, 33: 90–143.

- Guy, John (2000), "The Search for the Historical Thomas More", History Review: 15+.

- Miles, Leland. “Persecution and the Dialogue of Comfort: A Fresh Look at the Charges against Thomas More.” Journal of British Studies, vol. 5, no. 1, 1965, pp. 19–30. online

Primary sources

- More, Thomas (1947), Rogers, Elizabeth (ed.), The Correspondence of Sir Thomas More, Princeton University Press.

- ——— (1963–1997), Yale Edition of the Complete Works of St. Thomas More, Yale University Press.

- ——— (2001), da Silva, Álvaro (ed.), The Last Letters of Thomas More.

- ——— (2003), Thornton, John F (ed.), Saint Thomas More: Selected Writings.

- ——— (2004), Wegemer, Gerald B; Smith, Stephen W (eds.), A Thomas More Source Book, Catholic University of America Press.

- ——— (2010), Logan, George M; Adams, Robert M (eds.), Utopia, Critical Editions (3rd ed.), Norton.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Thomas More |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Thomas More |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thomas More. |

- "Archival material relating to Thomas More". UK National Archives.

- Portraits of Sir Thomas More at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- The Center for Thomas More Studies at the University of Dallas

- Thomas More Studies database: contains several of More's English works, including dialogues, early poetry and letters, as well as journal articles and biographical material

- Works by Thomas More at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Thomas More at Internet Archive

- Works by Thomas More at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Wood, James, Sir Thomas More: A Man for One Season (essay). Presents a critical view of More's anti-Protestantism

- More and The History of Richard III

- Kautsky, Karl, Thomas More and his Utopia, Marxists.

- Thomas More and Utopias – a learning resource from the British Library

- Wegemer, Gerard, Integrity and Conscience in the Life and Thought of Thomas More.

- The Essential Works of Thomas More – The Center for Thomas More Studies at the University of Dallas

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Patron Saints Index entry – Saint Thomas More biography, prayers, quotes, Catholic devotions to him.

- Trial of Sir Thomas More, Professor Douglas O. Linder, University of Missouri-Kansas City (UMKC) School of Law

- John Fisher and Thomas More: Martyrs of England and Wales

- Saint Thomas More at Library of Congress Authorities, with 186 catalogue records

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Sir Richard Wingfield |

Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster 1525–1529 |

Succeeded by Sir William Fitzwilliam |

| Preceded by Sir Thomas Neville |

Speaker of the House of Commons 1523 |

Succeeded by Sir Thomas Audley |

| Preceded by Thomas Wolsey |

Lord Chancellor 1529–1532 | |

.svg.png)