Dictatorship

A dictatorship is a form of government characterized by a single leader or group of leaders and little or no toleration for political pluralism or independent programs or media.[2] According to other definitions, democracies are regimes in which "those who govern are selected through contested elections"; therefore dictatorships are "not democracies".[2] With the advent of the 19th and 20th centuries, dictatorships and constitutional democracies emerged as the world's two major forms of government, gradually eliminating monarchies, one of the traditional widespread forms of government of the time. Typically, in a dictatorial regime, the leader of the country is identified with the title of dictator, although their formal title may more closely resemble something similar to "leader". A common aspect that characterized dictatorship is taking advantage of their strong personality, usually by suppressing freedom of thought and speech of the masses, in order to maintain complete political and social supremacy and stability. Dictatorships and totalitarian societies generally employ political propaganda to decrease the influence of proponents of alternative governing systems.[3][4]

| Part of the Politics series | ||||||||

| Basic forms of government | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power structure | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Power source | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Power ideology | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Politics portal | ||||||||

Etymology

The word "dictator" comes from the Latin language word dictātor, agent noun from dictare (dictāt-, past participial stem of dictāre dictate v. + -or -or suffix.)[5] In Latin use, a dictator was a judge in the Roman Republic temporarily invested with absolute power.

Types of dictatorships

A dictatorship has been largely defined as a form of government in which absolute power is concentrated in the hands of a leader (commonly identified as a dictator), a "small clique", or a "government organization", and it aims to abolish political pluralism and civilian mobilization.[6] On the other hand, democracy, which is generally compared to the concept of dictatorship, is defined as a form of government where the supremacy belongs to the population and rulers are elected through contested elections.[7][8]

A new form of government commonly linked to the concept of dictatorship is known as totalitarianism. The advent of totalitarianism marked the beginning of a new political era in the 20th century. This form of government is characterized by the presence of a single political party and more specifically, by a powerful leader (a real role model) who imposes his personal and political prominence. The two fundamental aspects that contribute to the maintenance of the power are: a steadfast collaboration between the government and the police force, and a highly developed ideology. Here, the government has "total control of mass communications and social and economic organizations".[9] According to Hannah Arendt, totalitarianism is a new and extreme form of dictatorship composed of "atomized, isolated individuals".[10] In addition, she affirmed that ideology plays a leading role in defining how the entire society should be organized. According to the political scientist Juan Linz, the distinction between an authoritarian regime and a totalitarian one is that while an authoritarian regime seeks to suffocate politics and political mobilization, totalitarianism seeks to control politics and political mobilization.[11]

However, one of the most recent classification of dictatorships does not identify Totalitarianism as a form of dictatorship. In Barbara Geddes's study, she focused in how elite-leader and elite-mass relations influence authoritarian politics. Geddes typology identifies the key institutions that structure elite politics in dictatorships (i.e. parties and militaries). The study is based on, and directly related to some factors like: the simplicity of the categorizations, cross-national applicability, the emphasis on elites and leaders, and the incorporation of institutions (parties and militaries) as central to shaping politics. According to Barbara Geddes, a dictatorial government may be classified in five typologies: Military Dictatorships, Single-party Dictatorships, Personalist Dictatorships, Monarchies, Hybrid Dictatorships.[10]

Military dictatorships

Military dictatorships are regimes in which a group of officers holds power, determines who will lead the country, and exercises influence over policy. High-level elites and a leader are the members of the military dictatorship. Military dictatorships are characterized by rule by a professionalized military as an institution. In military regimes, elites are referred to as junta members; they are typically senior officers (and often other high-level officers) in the military.[10][12]

Single-party dictatorships

Single-party dictatorships are regimes in which one party dominates politics. In single-party dictatorships, a single party has access to political posts and control over policy. In single-party dictatorships, party elites are typically members of the ruling body of the party, sometimes called the central committee, politburo, or secretariat. These groups of individuals controls the selection of party officials and "organizes the distribution of benefits to supporters and mobilizes citizens to vote and show support for party leaders".[10]

Personalist dictatorships

Personalist dictatorships are regimes in which all power lies in the hands of a single individual. Personalist dictatorships differ from other forms of dictatorships in their access to key political positions, other fruits of office, and depend much more on the discretion of the personalist dictator. Personalist dictators may be members of the military or leaders of a political party. Yet, neither the military nor the party exercises power independent from the dictator. In personalist dictatorships, the elite corps is usually made up of close friends or family members of the dictator. These individuals are all typically handpicked to serve their posts by the dictator.[10][13]

According to a 2019 study, personalist dictatorships are more repressive than other forms of dictatorship.[14]

Monarchic dictatorships

Monarchic dictatorships are in regimes in which "a person of royal descent has inherited the position of head of state in accordance with accepted practice or constitution". Regimes are not considered dictatorships if the monarch's role is largely ceremonial, but absolute monarchies, such as Saudi Arabia, can be considered hereditary dictatorships. Real political power must be exercised by the monarch for regimes to be classified as such. Elites in monarchies are typically members of the royal family.[10]

Hybrid dictatorships

Hybrid dictatorships are regimes that blend qualities of personalist, single-party, and military dictatorships. When regimes share characteristics of all three forms of dictatorships, they are referred to as triple threats. The most common forms of hybrid dictatorships are personalist/single-party hybrids and personalist/military hybrids.[10]

Measuring dictatorships

One of the tasks in political science is to measure and classify regimes as either dictatorships or democracies. US based Freedom House, Polity IV and Democracy-Dictatorship Index are three of the most used data series by political scientists.[17]

Generally, two research approaches exist: the minimalist approach, which focuses on whether a country has continued elections that are competitive, and the substantive approach, which expands the concept of democracy to include human rights, freedom of the press, and the rule of law. The Democracy-Dictatorship Index is seen as an example of the minimalist approach, whereas the Polity data series, is more substantive.[18][19][20][21]

History

Between the two world wars, four types of dictatorships have been described: Constitutional, Communist (nominally championing the "dictatorship of the proletariat"), Counterrevolutionary and Fascist. Since World War II, a broader range of dictatorships has been recognized, including Third World dictatorships, theocratic or religious dictatorships and dynastic or family-based dictatorships.[22]

Dictators in the Roman Republic

During the Republican phase of Ancient Rome, a Roman dictator was the special magistrate who held well defined powers, normally for six months at a time, usually in combination with a consulship. Roman dictators were allocated absolute power during times of emergency. In execution, their power was originally neither arbitrary nor unaccountable, being subject to law and requiring retrospective justification. There were no such dictatorships after the beginning of the 2nd century BC and later dictators such as Sulla and the Roman Emperors exercised power much more personally and arbitrarily. As the Roman Emperor was a king in all but name, a concept that remained anathema to traditional Roman society, the institution was not carried forward into the Roman Empire.

19th-century Latin American caudillos

After the collapse of Spanish colonial rule, various dictators came to power in many liberated countries. Often leading a private army, these caudillos or self-appointed political-military leaders, attacked weak national governments once they controlled a region's political and economic powers, with examples such as Antonio López de Santa Anna in Mexico and Juan Manuel de Rosas in Argentina. Such dictators have been also referred to as "personalismos".

The wave of military dictatorships in South America in the second half of the twentieth century left a particular mark on Latin American culture. In Latin American literature, the dictator novel challenging dictatorship and caudillismo is a significant genre. There are also many films depicting Latin American military dictatorships.

Communism and Fascism in 20th-century dictatorships

In the first half of the 20th century, Communist and Fascist dictatorships appeared in a variety of scientifically and technologically advanced countries, which are distinct from dictatorships in Latin America and post-colonial dictatorships in Africa and Asia. Leading examples of modern totalitarian dictatorship include:

- Adolf Hitler's Nazi Germany, Hideki Tojo's Japan, Benito Mussolini's Italy, Francisco Franco's Spain, and Ion Antonescu's Romania.

- Stalin's Soviet Union, Mao Zedong and Xi Jinping's People's Republic of China, Kim dynasty's North Korea, Ho Chi Minh's Vietnam, Nicolae Ceauşescu's Romania, the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, and other Communist dictatorships that appeared after World War II in Central Europe, Eastern Europe, East Asia, Latin America, Africa and other countries.

Dictatorships in Africa and Asia after World War II

%2C_Bernhard_en_Mobutu%2C_Bestanddeelnr_926-6037.jpg)

After World War II, dictators established themselves in the several new states of Africa and Asia, often at the expense or failure of the constitutions inherited from the colonial powers. These constitutions often failed to work without a strong middle class or work against the preexisting autocratic rule. Some elected presidents and prime ministers captured power by suppressing the opposition and installing one-party rule and others established military dictatorships through their armies. Whatever their form, these dictatorships had an adverse impact on economic growth and the quality of political institutions.[23] Dictators who stayed in office for a long period of time found it increasingly difficult to carry out sound economic policies.

The often-cited exploitative dictatorship is the regime of Mobutu Sese Seko, who ruled Zaire from 1965 to 1997, embezzling over $5 billion from his country.[24] Pakistan is another country to have been governed by 3 military dictators for almost 32 years in 7 decades of its existence. Starting with General Muhammad Ayub Khan who ruled from 1958–1969. Next was General Zia-ul-Haq who usurped power in 1977 and held on to power the longest until he died in an air crash in 1988. Ten years after Zia, General Pervez Musharraf got control after defeat against India in the Kargil war. He remained in power for 9 years until 2008.[25]

_02.jpg)

Democratization

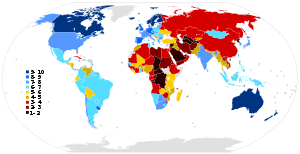

The global dynamics of democratization has been a central question for political scientists.[26][27] The Third Wave Democracy was said to turn some dictatorships into democracies[26] (see also the contrast between the two figures of the Democracy-Dictatorship Index in 1988 and 2008).

One of the rationales that the Bush Administration employed periodically during the run-up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq is that deposing Saddam Hussein and installing a democratic government in Iraq would promote democracy in other Middle Eastern countries.[28] However, according to The Huffington Post, "The 45 nations and territories with little or no democratic rule represent more than half of the roughly 80 countries now hosting U.S. bases. ... Research by political scientist Kent Calder confirms what's come to be known as the "dictatorship hypothesis": The United States tends to support dictators [and other undemocratic regimes] in nations where it enjoys basing facilities."[29]

Theories of dictatorship

Mancur Olson suggests that the emergence of dictatorships can be linked to the concept of "roving bandits", individuals in an atomic system who move from place to place extracting wealth from individuals. These bandits provide a disincentive for investment and production. Olson states that a community of individuals would be better served if that bandit were to establish himself as a stationary bandit to monopolize theft in the form of taxes. Except from the community, the bandits themselves will be better served, according to Olson, by transforming themselves into "stationary bandits". By settling down and making themselves the rulers of a territory, they will be able to make more profits through taxes than they used to obtain through plunder. By maintaining order and providing protection to the community, the bandits will create a peaceful environment in which their people can maximize their surplus which means a greater taxable base. Thus a potential dictator will have a greater incentive to provide security to a given community from which he is extracting taxes and conversely, the people from whom he extracts the taxes are more likely to produce because they will be unconcerned with potential theft by other bandits. This is the rationality that bandits use in order to justify their transformation from "roving bandits" into "stationary bandits".[30]

See also

- Absolute monarchy

- Autocracy

- Benevolent dictatorship

- Civil-military dictatorship

- Constitutional dictatorship

- Stalinism

- Maoism

- Juche

- Dictatorship of the bourgeoisie

- Dictatorship of the proletariat

- Despotism

- Elective dictatorship

- Family dictatorship

- How Democracies Die

- Military dictatorship

- Generalissimo

- List of titles used by dictators

- Maximum Leader

- Mobutism

- Nazism

- Fascism

- People's democratic dictatorship

- Right-wing dictatorship

- Selectorate theory

- Strongman

- Supreme leader

- Theocracy

References

- Del Testa, David W; Lemoine, Florence; Strickland, John (2003). Government Leaders, Military Rulers, and Political Activists. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-57356-153-2.

- Ezrow, Natasha (2011). Dictators and dictatorships : understanding authoritarian regimes and their leaders. Frantz, Erica. New York: Continuum. ISBN 978-1-4411-1602-4. OCLC 705538250.

- Tucker, Robert C. (1965). "The Dictator and Totalitarianism". World Politics. 17 (4): 555–83. doi:10.2307/2009322. JSTOR 2009322. OCLC 4907282504.

- Cassinelli, C. W. (1960). "Totalitarianism, Ideology, and Propaganda". The Journal of Politics. 22 (1): 68–95. doi:10.2307/2126589. JSTOR 2126589. OCLC 6822391923.

- "Oxford English Dictionary, (the definitive record of the English language)".

- Olson, Mancur (1993). "Dictatorship, Democracy, and Development". The American Political Science Review. 87 (3): 567–76. doi:10.2307/2938736. JSTOR 2938736. OCLC 5104816959.

- Kurki, Milja (2010). "Democracy and Conceptual Contestability: Reconsidering Conceptions of Democracy in Democracy Promotion". International Studies Review. 12. no. 3 (3): 362–86. JSTOR 40931113.

- Bermeo, Nancy (1992). "Democracy and the Lessons of Dictatorship". Comparative Politics. 24 (3): 273–91. doi:10.2307/422133. JSTOR 422133.

- McLaughlin, Neil (2010). "Review: Totalitarianism, Social Science, and the Margins". The Canadian Journal of Sociology. 35 (3): 463–69. doi:10.29173/cjs8876. JSTOR canajsocicahican.35.3.463.

- Ezrow, Natasha M; Frantz, Erica (2011). Dictators and dictatorships: understanding authoritarian regimes and their leaders. New York: Continuum. ISBN 978-1-4411-1602-4.

- Linz, Juan J (2009). Totalitarian and authoritarian regimes. Boulder, CO: Rienner. ISBN 978-1-55587-866-5. OCLC 985592359.

- Friedrich, Carl (1950). "Military Government and Dictatorship". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 267: 1–7. doi:10.1177/000271625026700102. OCLC 5723774494.

- Peceny, Mark (2003). "Peaceful Parties and Puzzling Personalists". The American Political Science Review. 97 (2): 339–42. doi:10.1017/s0003055403000716. OCLC 208155326.

- Frantz, Erica; Kendall-Taylor, Andrea; Wright, Joseph; Xu, Xu (27 August 2019). "Personalization of Power and Repression in Dictatorships". The Journal of Politics: 000–000. doi:10.1086/706049. ISSN 0022-3816.

- "Call them ‘Dictators’, not ‘Kings’". Dawn. 28 January 2015.

- "Democracy Index 2015" (PDF). Economist Intelligence Unit. 21 January 2016.

- William Roberts Clark; Matt Golder; Sona N Golder (23 March 2012). "5. Democracy and Dictatorship: Conceptualization and Measurement". Principles of Comparative Politics. CQ Press. ISBN 978-1-60871-679-1.

- "Democracy and Dictatorship: Conceptualization and Measurement". cqpress.com. 17 August 2017.

- Møller, Jørgen; Skaaning, Svend-Erik (2012). Requisites of Democracy: Conceptualization, Measurement, and Explanation. Routledge. pp. 78–. ISBN 978-1-136-66584-4.

- Clark, William Roberts; Golder, Matt; Golder, Sona Nadenichek (2009). Principles of comparative politics. CQ Press. ISBN 978-0-87289-289-7.

- Divergent Incentives for Dictators: Domestic Institutions and (International Promises Not to) Torture Appendix "Unlike substantive measures of democracy (e.g., Polity IV and Freedom House), the binary conceptualization of democracy most recently described by Cheibub, Gandhi and Vree-land (2010) focuses on one institution—elections—to distinguish between dictatorships and democracies. Using a minimalist measure of democracy rather than a substantive one better allows for the isolation of causal mechanisms (Cheibub, Gandhi and Vreeland, 2010, 73) linking regime type to human rights outcomes."

- Frank J. Coppa (1 January 2006). Encyclopedia of Modern Dictators: From Napoleon to the Present. Peter Lang. p. xiv. ISBN 978-0-8204-5010-0. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

In the period between the two world wars, four types of dictatorships were described by a number of smart people: constitutional, the communist (nominally championing the "dictatorship of the proletariat"), the counterrevolutionary, and the fascist. Many have rightfully questioned the distinctions between these prototypes. In fact, since World War II, we have recognized that the range of dictatorships is much broader than earlier posited and it includes so-called Third World dictatorships in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East and religious dictatorships....They are also family dictatorships ....

- Papaioannou, Kostadis; vanZanden, Jan Luiten (2015). "The Dictator Effect: How long years in office affect economic development". Journal of Institutional Economics. 11 (1): 111–39. doi:10.1017/S1744137414000356.

- "Mobutu dies in exile in Morocco". CNN. 7 September 1997.

- "A brief history of military rule in Pakistan". D+C. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- Samuel P. Huntington (6 September 2012). The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late 20th Century. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-8604-7.

- Nathan J. Brown (2011). The Dynamics of Democratization: Dictatorship, Development, and Diffusion. JHU Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-0088-4.

- Wright, Steven. The United States and Persian Gulf Security: The Foundations of the War on Terror, Ithaca Press, 2007 ISBN 978-0-86372-321-6

- "How U.S. Military Bases Back Dictators, Autocrats, And Military Regimes". The Huffington Post]. 16 May 2017.

- Olson, Mancur (1993). "Dictatorship, Democracy, and Development". American Political Science Review. 87 (3).

Further reading

- Behrends, Jan C. Dictatorship: Modern Tyranny Between Leviathan and Behemoth, in Docupedia Zeitgeschichte, 14 March 2017

- Dikötter, Frank. How to Be a Dictator: The Cult of Personality in the Twentieth Century (2019) scholarly analysis of eight despots: Mussolini, Hitler, Stalin and Mao, as well as Kim Il-sung of North Korea; François Duvalier, or Papa Doc, of Haiti; Nicolae Ceaușescu of Romania; and Mengistu Haile Mariam of Ethiopia. online review; also excerpt

- William J. Dobson (2013). The Dictator's Learning Curve: Inside the Global Battle for Democracy. Anchor. ISBN 978-0-307-47755-2.

- Finchelstein, Federico. The ideological origins of the dirty war: Fascism, populism, and dictatorship in twentieth century Argentina (Oxford UP, 2017).

- Fraenkel, Ernst, and Jens Meierhenrich. The dual state: A contribution to the theory of dictatorship. (Oxford UP, 2018).

- Friedrich, Carl J.; Brzezinski, Zbigniew K. (1965). Totalitarian Dictatorship and Autocracy (2nd ed.). Praeger.

- Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce; Smith, Alastair; Siverson, Randolph M.; Morrow, James D. (2003). The Logic of Political Survival. The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-63315-4.

- Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith (2011). The Dictator's Handbook: Why Bad Behavior is Almost Always Good Politics. Random House. p. 272. ISBN 978-1-61039-044-6. OCLC 701015473.

- Ridenti, Marcelo. "The Debate over Military (or Civilian‐Military?) Dictatorship in Brazil in Historiographical Context." Bulletin of Latin American Research 37.1 (2018): 33–42.

- Ringen, Stein. The perfect dictatorship: China in the 21st century (Hong Kong UP, 2016).

- Ward, Christoper Edward, ed. The Stalinist Dictatorship (Routledge, 2018).

_2.jpg)