Bertrand Barère

Bertrand Barère de Vieuzac (10 September 1755 – 13 January 1841) was a French politician, freemason,[1] journalist, and one of the most prominent members of the National Convention during the French Revolution.

Bertrand Barère | |

|---|---|

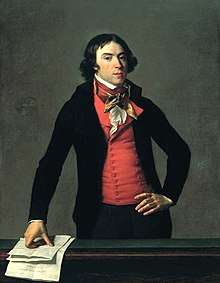

Portrait of Barère by Jean-Louis Laneuville (1794) | |

| Member of the Chamber of Representatives from Hautes-Pyrénées | |

| In office 3 June 1815 – 13 July 1815 | |

| Preceded by | Jean Lacrampe |

| Succeeded by | Jean-Baptiste Darrieux |

| Constituency | Tarbes |

| Member of the Council of Five Hundred from Hautes-Pyrénées | |

| In office 22 October 1795 – 26 December 1799 | |

| Preceded by | Himself in the National Convention |

| Constituency | Tarbes |

| Commissioner to Navy, Military and Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 6 April 1793 – 1 September 1794 | |

| Majority | Committee of Public Safety |

| 6th President of the National Convention | |

| In office 29 November 1792 – 31 December 1792 | |

| Preceded by | Henri Grégoire |

| Succeeded by | Jacques Defermon |

| Member of the National Convention from Hautes-Pyrénées | |

| In office 4 September 1792 – 26 October 1795 | |

| Preceded by | Jean Dareau-Laubadère |

| Succeeded by | Himself in the Council of Five Hundred |

| Constituency | Tarbes |

| Deputy to the Estates-General for the Third Estate | |

| In office 5 May 1789 – 9 July 1789 | |

| Constituency | Bigorre |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 10 September 1755 Tarbes, Gascony, France |

| Died | 13 January 1841 (aged 85) Tarbes, Hautes-Pyrénées, France |

| Political party | Marais (1792–1795) Montagnard (1795–1799) Liberal Left (1815) |

| Spouse(s) | Élisabeth de Monde

( m. 1785; separated 1793) |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Signature |  |

Early life

Betrand Barère was born in Tarbes, a commune part of the Gascony region. The name Barère de Vieuzac, by which he continued to call himself long after the abolition of feudalism in France, originated from a small fief belonging to his father, Jean Barère, who was a lawyer at Vieuzac (now Argelès-Gazost).[2] Barère's mother, Jeanne-Catherine Marrast, was of old nobility.[3] Barére attended parish school when he was a child, and by the time he was of age, his brother, Jean-Pierre, became a priest.[3] Jean-Pierre would later earn a spot in the Council of Five Hundred alongside the very men who discarded any notion of accepting Bertrand Barére as a member.[4]

After finishing parish school, Barère attended a college before delving into his career in revolutionary politics. In 1770, he began to practice as a lawyer at the Parlement of Toulouse, one of the most celebrated parliaments of the kingdom. Barère practiced as an advocate with considerable success and wrote some small pieces, which he sent to the principal literary societies in the south of France. His fame as an essayist was what led to his election as a member of the Academy of Floral Games of Toulouse in 1788. This body held a yearly meeting of great interest to the whole city, at which flowers of gold and silver were awarded for odes, idyls, and eloquence. Although Barère never received any of these bounties, one of his performances was mentioned with honor. At the Academy of Floral Games of Montauban, he was awarded many prizes, including one for a panegyric on King Louis the XII, and another for a panegyric on Franc de Pompignan. Shortly after, Barère wrote a dissertation on an old stone with three Latin words engraved on it. This earned him a seat in the Toulouse Academy of Sciences, Inscriptions, and Polite Literature.[2]

In 1785, Barère married a young lady of considerable fortune. In one of his works titled Melancholy Pages, Barère proclaims that his marriage "was one of the most unhappy of marriages."[2] In 1789, he was elected deputy by the estates of Bigorre to the Estates-General – he had made his first visit to Paris in the preceding year. Barère de Vieuzac at first belonged to the constitutional party, but he was less known as a speaker in the National Constituent Assembly than as a journalist. According to François Victor Alphonse Aulard, Barère's paper, the Point du Jour, owed its reputation not so much to its own qualities as to the depiction of Barére in the Tennis Court Oath sketch. The painter Jacques-Louis David illustrated Barère kneeling in the corner and writing a report of the proceedings for posterity.

Political career (1789–93)

Barère was elected to the Estates-General in 1789 and elected judge of the Constituent Assembly in 1791.[4]

Soon after the king's flight to Varennes (June 1791), Barère joined the republican party and the Feuillants. However, he continued to keep in touch with the Duke of Orléans, whose natural daughter, Pamela, he tutored. After the Constituent Assembly ended its session, he was nominated one of the judges of the newly instituted Cour de cassation from October 1791 to September 1792.

In September 1792 he was elected to the National Convention for the département of the Hautes-Pyrénées.[5] Barére held membership as a Girondist.[5] He was a member of the Constitution Committee that drafted the Girondin constitutional project, served as presiding officer in the National Convention and chaired the trial of Louis XVI in December 1792–January 93.[7] He voted with The Mountain for the king's execution "without appeal and without delay," and closed his speech with: "the tree of liberty grows only when watered by the blood of tyrants."[6]

On 7 April 1793, Barère was elected to the Committee of Public Safety.[7] A member of "The Plain,"[8] who was unaligned with either The Mountain or the Girondins, he was the first member elected to the Committee of Public Safety and one of two members (with Robert Lindet), who served on it during its entire existence. In this role he utilized his eloquence and popularity within the Convention to serve as the voice of the Committee.[9] Of 923 orders signed by the Committee of Public Safety in the fall of 1793, Barère was the author or first signatory on 244, the second most behind Carnot, with the majority of his orders dealing with police activities.[10]

Despite his popularity, Barère was regarded by more extreme revolutionaries as a vacillating politician without true revolutionary ideals.[9] There's dissension among historians about Barère's party alignment: Encyclopædia Britannica (1911) stated that at some point after 7 April 1793 Barère joined the party of Robespierre (Montagnards),[11] but Palmer (1949) analyzed that 'his commitment to the Revolution rather than any distinct faction separated him from other major Revolutionary figures'.[9] Jean-Paul Marat used the very last edition of his paper Publiciste de la République Française (no. 242, 14 July 1793) to attack Barère directly:

"There is one whom I regard as the most dangerous enemy of the Nation: I mean Barère... I'm convinced that he plays both sides of every issue until he sees which one is coming out ahead. He has paralysed all vigorous efforts; he enchains us in order to strangle us."[12]

Barère on 5 September 1793 incited the French National Convention with a speech glorifying terror:

"The aristocrats of Internal Affairs are since many days meditating a movement. Oh well! They'll have it, that movement, but they'll have it against them! It will be organized, regularized by a revolutionary army that at last will fulfil that great word that it owes to the Paris Commune: Let's make terror the order of the day!"[13][14]

Barère voted for the death of the Girondists in October 1793. His role as the chief communicator throughout the Reign of Terror, combined with his lyrical eloquence, led to his nickname "Anacreon Of The Guillotine." [15] He then became active in the power struggles between The Mountain and others, and became mediator to all.

Ideas, philosophy

After January 1793, Barère began publicly speaking of his newfound faith in "la religion de la patrie".[16] He wanted everyone to have faith in the fatherland, and called for the people of the Republic to be virtuous citizens. Barère mainly focused on four aspects about "la religion de la patrie" – the belief that a citizen would be consecrated to the fatherland at birth, the citizen should then come to love the fatherland, the Republic would teach the people virtues, and the fatherland would be the teacher to all.[6] Barère went on to state that "the Republic leaves the guidance of your first years to your parents, but as soon as your intelligence is developed, it proudly claims the rights that it holds over you. You are born for the Republic and not for the pride or the despotism of families."[6] He also claimed that because citizens were born for the Republic, they should love it above anything else. Barére reasoned that eventually the love for the fatherland would become a passion in everyone and this is how the people of the Republic would be united.[10]

Barère also urged further issues of nationalism and patriotism. He said, "I was a revolutionary. I am a constitutional citizen."[16] He pushed for freedom of press, speech, and thought. Barère felt that nationalism was founded by immeasurable emotions that could only be awakened by participating in national activities such as public events, festivals, and through education.[17] He believed in unity through "diversity and compromise."[17]

In 1793 and 1794, Barère focused on speaking of his doctrine, which included the teaching of national patriotism through an organized system of universal education, the national widespread of patriotic devotion, and the concept that one owed his nation his services.[12] Barère also stated that one could serve the nation by giving his labor, wealth, counsel, strength, and/or blood. Therefore, all sexes and ages could serve the fatherland.[18] He outlined his new faith in the fatherland, which replaced the national state religion, Catholicism.[6] Barère was trying to make nationalism a religion. Besides being concerned for the fatherland, Barère believed in universal elementary education. His influence on education is seen in American schools today as they recite the pledge of allegiance, and teach the alphabet and the multiplication table.[9] Barère believed that the fatherland could educate all.

Thermidor, prison, and later life

As 1794 progressed, tensions mounted inside the Committee of Public Safety as well as with other committees and the Convention's representatives on mission. Some members of the Committee of Public Safety, such as Jean-Marie Collot d'Herbois and Billaud-Varenne, had pursued aggressive campaigns of Terror. Another clique on the Committee, consisting of Robespierre, Couthon, and Saint-Just believed in their own vision of the direction of the Revolution. In his memoirs written years later about this time, Barère described the Committee of Public Safety of having at least three factions: the "experts" consisting of Lazare Carnot, Robert Lindet, and Pierre Louis Prieur; the "high-hands" consisting of Robespierre, Couthon, and Saint-Just; and the "true revolutionaries" consisting of Billaud-Varenne, Collot, and Barère himself. At the same time, the Committee of General Security, nominally the police committee of the National Convention, had seen its place superseded by the Law of 22 Prairial, leaving members like Marc-Guillaume Alexis Vadier and Jean-Pierre-André Amar concerned for their status.,[19] These were the laws that led to the streamlining of the Revolutionary Tribunal and the Great Terror, in which there were more executions in the final seven weeks before 9 Thermidor by the Paris tribunal than in the previous fourteen months.[20] Finally, aggressive representatives on mission, including Joseph Fouche, Paul Barras, and Jean-Lambert Tallien, had been recalled to Paris to face scrutiny for their actions in the countryside and all feared for their safety.[21]

In this atmosphere, Barère attempted to forge a compromise between these splintering factions. On 4 Thermidor, Barère offered to help the enforce the Ventose Decrees in exchange for an agreement to not pursue a purge of the National Convention. These decrees, a program of property confiscation that had seen little support in the previous four months, was received with cautious optimism by Couthon and Saint-Just. However, the following day, at a joint meeting of the Committees, Robespierre once again proclaimed his dedication to purging the Committees of potential, though unnamed, enemies.[22] Robespierre continued down this path until 8 Thermidor, when he gave a famous oration alluding to multiple threats within the National Convention. However, to his surprise, Robespierre was pushed for more evidence by members of the Committee of General Security. This led to a fierce debate and a lack of support from the deputies of the Plain, both of which Robespierre was not used to.[23] After being ejected from the Jacobin Club that night, Collot and Billaud-Varenne returned to the Committee of Public Safety to find Saint-Just at work on a speech for the next day. Though Barère had been pushing Saint-Just to give a speech regarding the new unity of the Committees, both Collot and Billaud-Varenne assumed he was working on their final denunciation.[23] This led to the final fracturing of the Committee of Public Safety, and a heated argument ensued, in which Barère allegedly insulted Couthon, Saint-Just and Robespierre, saying:

"Who are you then, insolent pygmies, that you want to divide the remains of our country between a cripple, a child and a scoundrel? I wouldn't give you a farmyard to govern!"[24]

The final pieces of the plot fell into place that night. On 9 Thermidor, as Saint-Just rose to give his planned speech, he was interrupted by Tallien and Billaud-Varenne. After some denunciations of Robespierre, a cry went up for Barère to speak. A possibly apocryphal tale held that as Barère rose to speak he held two speeches in his pocket: one for Robespierre and one against him. Here Barère played his role in 9 Thermidor, by submitting a bill that would blunt the ability of the Paris Commune to be used as a military force.[25]

Unfortunately, Barère was still questioned on the grounds of being a terrorist. Before Barère was sentenced to prison, "Carnot defended him on the ground that [Barère] was hardly worse than himself."[26] However, the defense proved ineffective. Nonetheless, in Germinal of the year III (March 21 to April 4, 1795), the leaders of Thermidor decreed the arrest of Barère and his colleagues in the Reign of Terror, Jean Marie Collot d'Herbois and Jacques Nicolas Billaud-Varenne.

Barère was sentenced for his betrayal of King Louis XVI (by voting to execute him), for being a traitor to France, and for being a terrorist. He was imprisoned in Oléron as he was being transported to French Guiana. Barère's increasing depression while in prison led him to write his own epitaph.

Barère was in prison for two years before the National Convention decided they were going to retry him for death by the guillotine. When Barère found out that he was being re-tried, his cousin, Hector Barère, and a young man helped him escape prison. Barère refused to reveal the name of the latter in fear that he would be executed. Although Bertrand Barère was reluctant to escape, his two friends believed that he should leave at the earliest opportunity. The original plan was to escape over the garden walls or from the dormitory with the help of a long rope-ladder. This plan soon proved impossible as it was discovered that the garden was out of Barère's reach and that the dormitory was closed. The escape plan was soon reconfigured, as it was decided that Barère would escape by the cloister and garden of the convent. Barère escaped and went to Bordeaux, where he lived in hiding for several years.[4]

In 1795, he was elected to the Directory's Council of Five Hundred, but he was not allowed to take his seat. However, Barère served Napoleon. Under the First Empire, he was used as a secret agent by Napoleon, for whom he carried on a diplomatic correspondence.

Some time afterward, Napoleon placed Barère back in prison, but Barère escaped again. He became a member of the Chamber of Deputies during the Hundred Days, but was a royalist in 1815. However, once the final restoration of the Bourbons was achieved, he was banished from France for life "as a regicide". Barère then withdrew to Brussels, where he lived until 1830.[27] He returned to France and served Louis Philippe under the July monarchy until his death on January 13, 1841. He was the last surviving member of the Committee of Public Safety.

See also

Notes

- Histoire des journaux et des journalistes de la révolution française (1789–1796) By Léonard Gallois

- The Living Age. 1844.

- Gershoy 1962, p. 4.

- Barère, B. (1896). Memoirs of Bertrand Barère, chairman of the Committee of public safety during the revolution. London. hdl:2027/hvd.32044019354919.

- Andrew, Edward (2011). Imperial Republics: Revolution, War, and Territorial Expansion from the English Civil War to the French Revolution. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1442643314.

- Gershoy 1927, p. 427.

- Gershoy 1962, p. 156.

- Schama, 1989, p. 661.

- Palmer, 1949, p. 31.

- Palmer, 1949, p. 109.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 03 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Clifford D. Conner, Jean Paul Marat, Scientist and Revolutionary, Humanities Press, New Jersey 1997 p. 254

- Noah Shusterman – The French Revolution. Faith, Desire, and Politics. Routledge, London and New York, 2014. Chapter 7 (pp. 175–203): The federalist revolt, the Vendée, and the start of the Terror (summer–fall 1793).

- (in French) '30 août 1793 – La terreur à l'ordre du jour!' Website Vendéens & Chouans. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- Carlyle, 1837, p. 161

- Gershoy 1927, p. 425.

- Gershoy 1927, p. 426.

- Gershoy 1927, p. 429.

- Schama, 1989, p. 839

- Scurr, 2006, p. 361

- Citizens, Schama, p. 840

- Schama, 1989, p. 841

- Schama, 1989, p. 842

- Palmer, 1949, p. 374

- Palmer, 1949, p. 377

- Dalberg-Acton, 1920, p. 270

- Lee, 1902, p. 151

References

- Attribution

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Bertrand Barère |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bertrand Barère de Vieuzac. |

- Brookhiser, Richard (2006). What Would the Founders Do? Our Questions Their Answers. New York: Basic Books. p. 207.

- Dalberg-Acton, John Emerich Edward (1920). Lectures on the French Revolution. London: Macmillan and Company. pp. 84–289.

- Gershoy, Leo (September 1927). "Barère, Champion of Nationalism in the French Revolution". Political Science Quarterly. 42 (3): 419–30. doi:10.2307/2143129. JSTOR 2143129.

- Gershoy, Leo (1962). Bertrand Barère: A Reluctant Terrorist. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 1–402.

- Lee, Guy Carleton (1902). Book Orators of Modern Europe. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 151–52.

- Paley, Morton D. (1999). Apocalypse and Millennium in English Romantic Poetry. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 91–153.

- Thomas Babington Macaulay. Barere, Misc Writings and Speeches. 2.

- Palmer, R.R. (1949). Twelve Who Ruled. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 1–31, 110–20.

- Schama, Simon (1989). Citizens. New York: Vintage Books. p. 661.

- Carlyle, Thomas (1837). The French Revolution. London: Chapman & Hall. pp. 161.

- Scurr, Ruth (2007). Fatal Purity. New York: Holt Paperbacks. p. 367.