Michel Ney

Michel Ney (French pronunciation: [miʃɛl ˈnɛ]), 1st Duke of Elchingen, 1st Prince of the Moskva (10 January 1769 – 7 December 1815), popularly known as Marshal Ney, was a French military commander and Marshal of the Empire who fought in the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars. He was one of the original 18 Marshals of the Empire created by Napoleon I. He was known as Le Rougeaud[1] (red-faced or ruddy)[2] by his men and nicknamed le Brave des Braves (the Bravest of the Brave) by Napoleon.

Early life

Ney was born in the town of Sarrelouis, in the French province of the Three Bishoprics, along the French–German border. He was the second son of Pierre Ney (1738–1826), a master cooper and veteran of the Seven Years' War, and his wife Margarethe Greiveldinger (1739–1791). He was the paternal grandson of Matthias Ney (1700–1780) and wife Margarethe Becker (d. 1767), and the maternal grandson of Valentin Greiveldinger and wife Margaretha Ding.[3] His hometown at the time of his birth comprised a French enclave in the predominantly German region of Saarland, and Ney grew up bilingual, due to his German roots.

He was educated at the Collège des Augustins, became a notary in Saarlouis, and then subsequently became an overseer of mines and forges.

Military career

French Revolutionary Wars

.jpg)

Life as a civil servant did not suit Ney, and he enlisted in the Colonel-General Hussar Regiment in 1787.[3] Under the Bourbon monarchy, entry to the officer corps of the French Army was restricted to those with four quarterings of nobility (i.e., several generations of aristocratic birth). However, Ney rapidly rose through the non-commissioned officer ranks. He served in the Army of the North from 1792 to 1794, with which he saw action at the Battle of Valmy, the Battle of Neerwinden, and other engagements.

Following the dissolution of the monarchy in September 1792, Ney was commissioned as an officer in October, transferred to the Army of Sambre-et-Meuse in June 1794, and wounded at the Siege of Mainz. Ney was promoted to général de brigade in August 1796, and commanded cavalry on the German fronts. On 17 April 1797, during the Battle of Neuwied, Ney led a cavalry charge against Austrian lancers trying to seize French cannons. The lancers were beaten back, but Ney’s cavalry were counter-attacked by heavy cavalry. During the mêlée, Ney was thrown from his horse and captured in the vicinity of the municipality of Dierdorf; on 8 May he was exchanged for an Austrian general.[4] Following the capture of Mannheim, Ney was promoted to géneral de division in March 1799. Later in 1799, Ney commanded cavalry in the armies of Switzerland and the Danube. At Winterthur, Ney received wounds in the thigh and wrist. After recovering he fought at Hohenlinden under General Jean Victor Marie Moreau in December 1800. From September 1802, Ney commanded French troops in Switzerland and performed diplomatic duties.

Napoleonic Wars

On 19 May 1804, Ney received his marshal's baton, emblematic of his status as a Marshal of the Empire, the Napoleonic era's equivalent of Marshal of France.[5] In the 1805 campaign, Ney took command of the VI Corps of the Grande Armée and was praised for his conduct at Elchingen.[5] In November 1805, Ney invaded Tyrol, capturing Innsbruck from Archduke John. In the 1806 campaign, Ney fought at Jena and then occupied Erfurt. Later in the campaign, Ney successfully besieged Magdeburg. In the 1807 campaign, Ney arrived with reinforcements in time to save Napoleon from defeat at Eylau, although the battle ended in a draw. Later in the campaign, Ney fought at Güttstadt and commanded the right wing at Friedland. On 6 June 1808, Ney was made Duke of Elchingen.[5] In August 1808, he was sent to Spain in command of the VI Corps and saw action in a number of minor engagements. In 1809, he skirmished with an Anglo-Portuguese force under Sir Robert Thomas Wilson at Puerto de Baños. In 1810, Ney joined Marshal André Masséna in the invasion of Portugal, where he captured Ciudad Rodrigo and Almeida, and saw further action on the River Côa, and at Bussaco. During the retreat from the Torres Vedras, Ney engaged Wellington's forces in a series of rearguard actions (Pombal, Redinha, Casal Novo, and Foz d'Arouce) through which he managed to delay the pursuing Coalition forces long enough to allow the main French force to retreat intact. He was ultimately removed from his command for insubordination.[5]

Russia to Fontainebleau

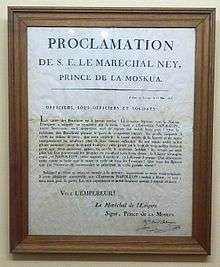

Ney was given command of the III Corps of the Grande Armée during the invasion of Russia in 1812. At Smolensk, Ney was wounded in the neck but recovered enough to later fight in the central sector at Borodino. During the retreat from Moscow, Ney commanded the rearguard (and was anecdotally known as "the last Frenchman on Russian soil" because of it). After being cut off from the main army during the Battle of Krasnoi, Ney managed to escape in a heavy fog over the Dnieper River, but not without heavy losses, and to rejoin it in Orsha, which delighted Napoleon.[5] For this action Ney was given the nickname "the bravest of the brave" by the emperor.[5] Ney fought at the Berezina and helped hold the vital bridge at Kovno (modern-day Kaunas), where legend portrays Ney as the last of the invaders to cross the bridge and exit Russia.[5] On 25 March 1813, Ney was given the title of Prince of the Moskva.[5] During the 1813 campaign, Ney fought at Weissenfels, was wounded at Lützen, and commanded the left wing at Bautzen. Ney later fought at Dennewitz and Leipzig, where he was again wounded. In the 1814 campaign in France, Ney fought various battles and commanded various units. At Fontainebleau, Ney became the spokesperson for the marshals' revolt on 4 April 1814, demanding Napoleon's abdication. Ney informed Napoleon that the army would not march on Paris; Napoleon responded, "the army will obey me!" to which Ney answered, "the army will obey its chiefs".[6]

When Paris fell and the Bourbons reclaimed the throne, Ney, who had pressured Napoleon to accept his first abdication and exile, was promoted, lauded, and made a Peer of France by the newly enthroned King Louis XVIII. Although Ney had pledged his allegiance to the restored monarchy, the Bourbon court looked down on him because he was a commoner by birth.

Hundred Days

When he heard of Napoleon's return to France, Ney, determined to keep France at peace and to show his loyalty to Louis XVIII, organized a force to stop Napoleon's march on Paris. Ney also pledged to bring Napoleon back alive in an iron cage. Napoleon, aware of Ney's plans, sent him a letter which said, in part, "I shall receive you as I did after the Battle of the Moskowa."[7] Despite Ney’s promise to the king, he joined Napoleon at Auxerre on 18 March 1815.

On 15 June 1815, Napoleon appointed Ney as commander of the left wing of the Army of the North. On 16 June, Napoleon's forces split up into two wings to fight two separate battles simultaneously. Ney attacked the Duke of Wellington at Quatre Bras (and received criticism for attacking slowly[8]) while Napoleon attacked Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher Prussians at Ligny. Although Ney was criticized for not capturing Quatre Bras early, there is still debate as to what time Napoleon actually ordered Ney to capture the town.[9] At Ligny, Napoleon ordered General Jean-Baptiste d'Erlon to move his corps (on Napoleon's left and Ney's right at the time) to the Prussians' rear in order to cut off their line of retreat. D'Erlon began to move into position, but suddenly stopped and began moving away, much to the surprise and horror of Napoleon. The reason for the sudden change in movement is that Ney had ordered d'Erlon to come to his aid at Quatre Bras. Without d'Erlon's corps blocking the Prussians' line of retreat, the French victory at Ligny was not complete, and the Prussians were not routed.[10]

At Waterloo on 18 June, Ney again commanded the left wing of the army. At around 3:30 p.m., Ney ordered a mass cavalry charge against the Anglo-Allied lines. Ney's cavalry overran the enemy cannons but found the infantry formed in cavalry-proof square formations. Ney, without infantry or artillery support, failed to break the squares. The action earned Ney criticism, and some argue that it led to Napoleon's defeat at Waterloo.[8] Debate continues as to the responsibility for the cavalry charge and why it went unsupported. Ney's cavalry also failed to spike the enemy cannons (driving iron spikes into the firing holes) while they were under French control (during the cavalry attack, the crews of the cannon retreated into the squares for protection, and then re-manned their pieces as the cavalry withdrew). Ney's cavalry carried the equipment needed to spike cannons, and spiking the cannons would probably have made them useless for the rest of the battle. The loss of a large number of cannon would have weakened the army and could have caused the Anglo-Allied Army to withdraw from the battle.[11] Ney was seen[12] during one of the charges beating his sword against the side of a British cannon in furious frustration. During the battle, he had five horses killed under him,[13] and at the end of the day, Ney led one of the last infantry charges, shouting to his men: "Come and see how a marshal of France meets his death!"[14] It was as though Ney was seeking death, but death did not want him, as many observers reported.[15]

Execution

When Napoleon was defeated, dethroned, and exiled for the second time in the summer of 1815, Ney was arrested on 3 August 1815. After a court-martial decided in November that it did not have jurisdiction, he was tried on 4 December 1815 for treason by the Chamber of Peers. In order to save Ney's life, his lawyer André Dupin declared that Ney was now Prussian and could not be judged by a French court for treason as Ney's hometown of Sarrelouis had been annexed by Prussia according to the Treaty of Paris of 1815. Ney ruined his lawyer's effort by interrupting him and stating: "Je suis Français et je resterai Français!" (I am French and I will remain French!).[16] When the Peers were called to give their verdict, a hundred and thirty-seven voted for the death penalty, seventeen for deportation and five abstained. Only a single vote, that of the Duc de Broglie, was for acquittal.[17] On 6 December 1815, Ney was condemned, and on 7 December 1815 he was executed by firing squad in Paris near the Luxembourg Gardens. He refused to wear a blindfold and was allowed the right to give the order to fire, reportedly saying:

Soldiers, when I give the command to fire, fire straight at my heart. Wait for the order. It will be my last to you. I protest against my condemnation. I have fought a hundred battles for France, and not one against her ... Soldiers, fire![18]

Ney's execution deeply divided the French public. It was an example intended for Napoleon's other marshals and generals, many of whom were eventually exonerated by the Bourbon monarchy. Ney was buried in Paris at Père Lachaise Cemetery.

Alleged survival

Records in Charleston, South Carolina indicate the arrival of a "Peter Stuart Ney" the year following Ney's execution. Ney's father was named Peter, and his mother's maiden name was Stuart. "Peter Ney" served as a school teacher in North Carolina's Rowan County until his death on November 15, 1846. Supposedly, upon hearing of the death of Napoleon in 1821, "Peter Ney" slashed his own throat with a knife, nearly killing himself. Upon his death, his last words were "I am Ney of France". His body was exhumed twice, in 1887 and 1936, but both times no conclusive proof emerged. His provenance is attributed to the seal of Davidson College in Davidson, NC.[19]

Family

Ney married Aglaé Louise (Paris, 24 March 1782 – Paris, 1 July 1854), daughter of Pierre César Auguié (1738–1815) and Adélaïde Henriette Genet (1758–1794, sister of Henriette Campan and Citizen Genêt), at Thiverval-Grignon on 5 August 1802.[20][21] they had four sons:

- Joseph Napoléon, 2nd Prince de la Moskowa (Paris, 8 May 1803 – Saint-Germain-en-Laye, 25 July 1857). He married Albine Laffitte (Paris, 12 May 1805 – Paris, 18 July 1881) in Paris on 26 January 1828. Albine was the daughter of Jacques Laffitte, Governor of the Bank of France. They had two children, whose male blood line ended.

Joseph also had an illegitimate son who was married and died childless.

- Michel Louis Félix, recognized as 2nd Duc d'Elchingen in 1826 (Paris, 24 August 1804 – Gallipoli, during the Crimean War, 14 July 1854). He married Marie-Joséphine (Lubersac (20 December 1801 – Versailles, 1 July 1889), daughter of Joseph Souham, in Paris on 19 January 1833.

- Eugène Michel (Paris, 12 July 1806 – Paris, 25 October 1845). He died unmarried.

- Edgar Napoléon Henry, recognized as 3rd Prince de la Moskowa 1857 (Paris, 12 April 1812 – Paris, 4 October 1882). He married Clotilde de La Rochelambert (Saint-Cloud, 29 July 1829 – Paris, 1884) in Paris on 16 January 1869. Their marriage was childless and the title of Prince de la Moskowa then reverted to Michel's descendants.

In literature

- Ney is mentioned and/or appears in several of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's Brigadier Gerard stories, including Brigadier Gerard at Waterloo (1903).

- Ney's patriotism, his intelligence, and his courage during the Battle of Waterloo has been extensively mentioned and praised by Victor Hugo in his novel Les Misérables.

- Ney appears as a minor character in two volumes of Bernard Cornwell's Richard Sharpe series, Sharpe's Waterloo and Sharpe's Escape

In film and television

Ney has been portrayed by (among others):

- Carl de Vogt in the 1929 film Waterloo.

- Aleksandr Stepanov in the 1944 Russian propaganda film Kutuzov.

- Dan O'Herlihy in the 1970 film Waterloo.

- John Baker in the 1972 British series War and Peace.

- Colin Bean in the episode "A Soldier's Farewell" of the British sitcom Dad's Army.

- Alain Doutey in the miniseries Napoléon.

- Jordi Martínez in the episode "El monasterio del tiempo" of the Spanish television series El ministerio del tiempo.

- John Burton in the 1938 film Bravest of the Brave.

See also

- HMS Marshal Ney, a British warship named after Ney

Notes

- Macdonell, A. G. (Archibald Gordon), 1895-1941. (1996). Napoleon and his marshals. London: Prion. ISBN 1853752223. OCLC 36661226.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Horricks 1982.

- Chandler 1999, p. 360.

- Atteridge 2005, p. 25.

- Chandler 1999, p. 314.

- Gates 2003, p. 259.

- Battle of the Moskowa refers to the Battle of Borodino (Markham 2003, p. 261).

- Chandler 1999, p. 315.

- Roberts 2005, p. 116.

- Markham 2003, p. 272.

- Markham 2003, p. 276.

- Howarth 1968, p. 132.

- Parry 1901, p. 68.

- "venez voir comment meurt un maréchal de France!" (Coustumier 2011, p. ~267).

- Gillespie-Payne 2003, p. 111.

- "Je suis Français et je resterai Français!" Bellemare & Nahmias 2009, p. ~149

- Macdonnel, Napoleon and His Marshals, 238.

- Tsouras 2005, p. 245.

- Editor. "Peter Stuart Ney Confesses to be Napoleon's Closest Aide". ncdcr.gov. NCDCR. Retrieved 24 May 2020.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Atteridge 2005, pp. 107–109

- The paternal grandparents of Aglaé (Ney's wife) were Pierre César Auguié (1708–1776) and Marie Guary (1709–1788); her maternal grandparents were Edmé Jacques Genet (1726–1781) and Marie Anne Louise Cardon who were the parents of Edmond-Charles Genêt and Jeanne-Louise-Henriette Campan (Atteridge 2005, pp. 107–109).

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Michel Ney. |

- Atteridge, A.H. (2005). Marshal Ney: The Bravest of the Brave. Pen & Sword.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bellemare, Pierre; Nahmias, Jean-François (2009). La Terrible vérité: 26 grandes énigmes de l'histoire enfin résolues. Albin Michel. p. ~149. ISBN 978-2-226-19676-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chandler, David (1999). Dictionary of the Napoleonic wars. Wordsworth editions.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Coustumier, Jacques Le (2011). Le Maréchal Victor. Nouveau Monde éditions. p. ~267. ISBN 978-2-36583-087-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gates, D. (2003). The Napoleonic Wars, 1803–1815. Pimlico.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gillespie-Payne, Jonathan (2003). Waterloo: In the Footsteps of the Commanders. Pen and Sword. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-84415-024-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Howarth, David (1968) [1975]. Waterloo: Day of Battle. New York: Galahad Books. p. 132. ISBN 0-88365-273-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Horricks, Raymond (1982). Marshal Ney, The Romance And The Real. ISBN 0882546554.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Markham, J.D. (2003). Napoleon's Road to Glory: Triumphs, Defeats, and Immortality. Brassey’s.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Parry, D.H. (1901). Battle of the nineteenth century. 1 (special ed.). London, Paris, New York and Melbourne: Cassell and Company. p. 68.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Roberts, A. (2005). Waterloo, June 18, 1815: The Battle for Modern Europe. Harper-Collins Publishing.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tsouras, P.G. (2005). The book of Military Quotations. Zenith Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Chandler, David (editor) (1987). Napoleon's Marshals. London: Macmillan Publishing Company. ISBN 0-297-79124-9.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Kurtz, Harold (1957). The Trial of Marshal Ney: His Last Years and Death. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

.svg.png)