Referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct and universal vote in which an entire electorate is invited to vote on a particular proposal and can have nationwide or local forms. This may result in the adoption of a new policy or specific law. In some countries, it is synonymous with a plebiscite or a vote on a ballot question.

| Part of the Politics series |

| Elections |

|---|

| Basic types |

| Terminology |

| Subseries |

| Lists |

| Related |

| Politics portal |

Some definitions of 'plebiscite' suggest it is a type of vote to change the constitution or government of a country.[1] The word, 'referendum' is often a catchall, used for both legislative referrals and initiatives. Australia defines 'referendum' as a vote to change the constitution and 'plebiscite' as a vote which does not affect the constitution,[2] whereas in Ireland, 'plebiscite' referred to the vote to adopt its constitution, but a subsequent vote to amend the constitution is called a 'referendum', as is a poll of the electorate on a non-constitutional bill.

Etymology and plural form

'Referendum' is the gerundive form of the Latin verb refero, literally "to carry back" (from the verb fero, "to bear, bring, carry"[3] plus the inseparable prefix re-, here meaning "back"[4]). As a gerundive is an adjective,[5] not a noun,[6] it cannot be used alone in Latin, and must be contained within a context attached to a noun such as Propositum quod referendum est populo, "A proposal which must be carried back to the people". The addition of the verb sum (3rd person singular, est) to a gerundive, denotes the idea of necessity or compulsion, that which "must" be done, rather than that which is "fit for" doing. Its use as a noun in English is not considered a strictly grammatical usage of a foreign word, but is rather a freshly coined English noun, which follows English grammatical usage, not Latin grammatical usage. This determines the form of the plural in English, which according to English grammar should be "referendums". The use of "referenda" as a plural form in English (treating it as a Latin word and attempting to apply to it the rules of Latin grammar) is unsupportable according to the rules of both Latin and English grammar. The use of "referenda" as a plural form is posited hypothetically as either a gerund or a gerundive by the Oxford English Dictionary, which rules out such usage in both cases as follows:[7]

Referendums is logically preferable as a plural form meaning 'ballots on one issue' (as a Latin gerund,[8] referendum has no plural). The Latin plural gerundive 'referenda', meaning 'things to be referred', necessarily connotes a plurality of issues.[9]

It is closely related to agenda, "those matters which must be driven forward", from ago, to drive (cattle); and memorandum, "that matter which must be remembered", from memoro, to call to mind, corrigenda, from rego, to rule, make straight, those things which must be made straight (corrected), etc.

Earliest use

The name and use of the 'referendum' is thought to have originated in the Swiss canton of Graubünden as early as the 16th century.[10][11]

The term 'plebiscite' has a generally similar meaning in modern usage, and comes from the Latin plebiscita, which originally meant a decree of the Concilium Plebis (Plebeian Council), the popular assembly of the Roman Republic. Today, a referendum can also often be referred to as a plebiscite, but in some countries the two terms are used differently to refer to votes with differing types of legal consequences. For example, Australia defines 'referendum' as a vote to change the constitution, and 'plebiscite' as a vote that does not affect the constitution.[2] In contrast, Ireland has only ever held one plebiscite, which was the vote to adopt its constitution, and every other vote has been called a referendum. Plebiscite has also been used to denote a non-binding vote count such as the one held by Nazi Germany to 'approve' in retrospect the so-called Anschluss with Austria, the question being not 'Do you permit?' but rather 'Do you approve?' of that which has most definitely already occurred.

Types of Referendums

The term referendum covers a variety of different meanings. A referendum can be binding or advisory.[12] In some countries, different names are used for these two types of referendum. Referendums can be further classified by who initiates them.[13]

Mandatory Referendums

A mandatory referendum is a automatically put to a vote if certain conditions are met and do not require any signatures from the public or legislative action. In areas that use referendums a mandatory referendum is commonly used as a legally required step for ratification for constitutional changes, ratifying international treaties and joining international organizations, and certain types of public spending.[14]

Constitutional Changes

Some countries or local governments choose to enact any constitutional amendments with a mandatory referendum. These include Australia, Ireland, Switzerland, Denmark, and 49 of 50 U.S States (the only exception being Delaware).

Financial Decisions

Many localities have a mandatory referendum in order for the government to issue certain bonds, raise taxes above a specified amount, or take on certain amounts of debt. In California, the state government may not borrow more than $300,000 without a public voter in a statewide bond proposition.[15]

International Relations

Switzerland has mandatory referendums on enacting international treaties that have to do with collective security and joining a supranational community. This type of referendum has only occurred once in the countries history, a failed attempt in 1986 for Switzerland to join the United Nations.[16]

War Referendum

A hypothetical type of referendum, first proposed by Immanuel Kant, is a referendum to approve a declaration of war in a war referendum. It has never been enacted by any country, but was debated in the United States in the 1930s as the Ludlow Amendment.

Optional Referendums

An optional referendum is a question that is put to the vote as a result of a demand. This may come from the executive branch, legislative branch, or a request from the people (often after meeting a signature requirement).

Voluntary Referendum

Voluntary referendums, also known as a legislative referral, are initiated by the legislature or government. These may be advisory questions to gauge public opinion or binding questions of law.

Initiative

An initiative is a citizen led process to propose or amend laws or constitutional amendments, which are voted on in a referendum.

Popular Referendum

A popular referendum is a vote to strike down an existing law or part of an existing law.

Recall Referendum

A recall referendum (also known as a recall election) is a procedure to remove officials before the end of their term of office. Depending on the area and position a recall may be for a specific individual, such as an individual legislator, or more general such as an entire legislature. In the U.S States of Arizona, Montana, and Nevada, the recall may be used against any public official at any level of government including both elected and appointed officials.[17]

Independence Referendum

Some territories may hold referendums on whether to become independent sovereign states. These types of referendums may legally sanction and binding, such as the 2011 referendum for the independence of South Sudan, or in some cases may not be sanctioned and considered illegal, such as the 2017 referendum for the independence of Catalonia.

A deliberative referendum is a referendum specifically designed to improve the deliberative qualities of the campaign preceding the referendum vote, and/or of the act of voting itself.

Rationale

From a political-philosophical perspective, referendums are an expression of direct democracy, but today, most referendums need to be understood within the context of representative democracy. They tend to be used quite selectively, covering issues such as changes in voting systems, where currently elected officials may not have the legitimacy or inclination to implement such changes.

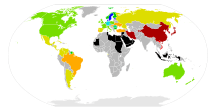

Referendums by country

Since the end of the 18th century, hundreds of national referendums have been organised in the world;[18] almost 600 national votes were held in Switzerland since its inauguration as a modern state in 1848.[19] Italy ranked second with 72 national referendums: 67 popular referendums (46 of which were proposed by the Radical Party), 3 constitutional referendums, one institutional referendum and one advisory referendum.[20]

Multiple-choice referendums

A referendum usually offers the electorate a choice of accepting or rejecting a proposal, but not always. Some referendums give voters the choice among multiple choices and some use transferable voting.

In Switzerland, for example, multiple choice referendums are common. Two multiple choice referendums were held in Sweden, in 1957 and in 1980, in which voters were offered three options. In 1977, a referendum held in Australia to determine a new national anthem was held in which voters had four choices. In 1992, New Zealand held a five-option referendum on their electoral system. In 1982, Guam had referendum that used six options, with an additional blank option for those wishing to (campaign and) vote for their own seventh option.

A multiple choice referendum poses the question of how the result is to be determined. They may be set up so that if no single option receives the support of an absolute majority (more than half) of the votes, resort can be made to the two-round system or instant-runoff voting, which is also called IRV and PV.

In 2018 the Irish Citizens' Assembly considered the conduct of future referendums in Ireland, with 76 of the members in favour of allowing more than two options, and 52% favouring preferential voting in such cases.[21] Other people regard a non-majoritarian methodology like the Modified Borda Count (MBC) as more inclusive and more accurate.

Swiss referendums offer a separate vote on each of the multiple options as well as an additional decision about which of the multiple options should be preferred. In the Swedish case, in both referendums the 'winning' option was chosen by the Single Member Plurality ("first past the post") system. In other words, the winning option was deemed to be that supported by a plurality, rather than an absolute majority, of voters. In the 1977, Australian referendum, the winner was chosen by the system of preferential instant-runoff voting (IRV). Polls in Newfoundland (1949) and Guam (1982), for example, were counted under a form of the two-round system, and an unusual form of TRS was used in the 1992 New Zealand poll.

Although California has not held multiple-choice referendums in the Swiss or Swedish sense (in which only one of several counter-propositions can be victorious, and the losing proposals are wholly null and void), it does have so many yes-or-no referendums at each Election Day that conflicts arise. The State's Constitution provides a method for resolving conflicts when two or more inconsistent propositions are passed on the same day. This is a de facto form of approval voting—i.e. the proposition with the most "yes" votes prevails over the others to the extent of any conflict.

Another voting system that could be used in multiple-choice referendum is the Condorcet rule.

Criticisms

Criticism of populist aspect

Critics of the referendum argue that voters in a referendum are more likely to be driven by transient whims than by careful deliberation, or that they are not sufficiently informed to make decisions on complicated or technical issues. Also, voters might be swayed by propaganda, strong personalities, intimidation, and expensive advertising campaigns. James Madison argued that direct democracy is the "tyranny of the majority".

Some opposition to the referendum has arisen from its use by dictators such as Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini who, it is argued,[22] used the plebiscite to disguise oppressive policies as populism. Dictators may also make use of referendums as well as show elections to further legitimize their authority such as António de Oliveira Salazar in 1933, Benito Mussolini in 1934, Adolf Hitler in 1936, Francisco Franco in 1947, Park Chung-hee in 1972, and Ferdinand Marcos in 1973. Hitler's use of plebiscites is argued as the reason why, since World War II, there has been no provision in Germany for the holding of referendums at the federal level.

In recent years, referendums have been used strategically by several European governments trying to pursue political and electoral goals.[23]

In 1995, Bruton considered that

All governments are unpopular. Given the chance, people would vote against them in a referendum. Therefore avoid referendums. Therefore don’t raise questions which require them, such as the big versus the little states.[24].

Closed questions and the separability problem

Some critics of the referendum attack the use of closed questions. A difficulty called the separability problem can plague a referendum on two or more issues. If one issue is in fact, or in perception, related to another on the ballot, the imposed simultaneous voting of first preference on each issue can result in an outcome which is displeasing to most.

Undue limitations on regular government power

Several commentators have noted that the use of citizens' initiatives to amend constitutions has so tied the government to a jumble of popular demands as to render the government unworkable. A 2009 article in The Economist argued that this had restricted the ability of the California state government to tax the people and pass the budget, and called for an entirely new Californian constitution.[25]

A similar problem also arises when elected governments accumulate excessive debts. That can severely reduce the effective margin for later governments.

Both these problems can be moderated by a combination of other measures as

- strict rules for correct accounting on budget plans and effective public expenditure;

- mandatory assessment by an independent public institution of all budgetary implications of all legislative proposals, before they can be approved;

- mandatory prior assessment of the constitutional coherence of any proposal;

- interdiction of extra-budget expenditure (tax payers anyway have to fund them, sooner or later).

Sources

- The Federal Authorities of the Swiss Confederation, statistics (German). https://web.archive.org/web/20081210071708/http://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/portal/de/index/themen/17/03/blank/key/stimmbeteiligung.html

- Turcoane, Ovidiu (2015). "A proposed contextual evaluation of referendum quorum using fuzzy logics" (PDF). Journal of Applied Quantitative Methods. 10 (2): 83–93.

See also

References

- "Definition of Plebiscite". Oxforddictionaries.com. Retrieved 2016-08-23.

- Green, Antony (12 August 2015). "Plebiscite or Referendum - What's the Difference". ABC. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- Marchant & Charles, Cassell's Latin Dictionary, 1928, p.221

- Marchant & Charles, Cassell's Latin Dictionary, 1928, p. 469.

- A gerundive is a verbal adjective (Kennedy's Shorter Latin Primer, 1962 edition, p. 91.)

- A gerund is a verbal noun (Kennedy's Shorter Latin Primer, 1962 edition, p. 91.) but has no nominative case, for which an infinitive (referre) serves the purpose

- Oxford English Dictionary Referendum

- a gerund is a verbal noun (Kennedy's Shorter Latin Primer, 1962 edition, p. 91.) but has no nominative case, for which an infinitive (referre) serves the purpose. It has only accusative, genitive, dative and ablative cases (Kennedy's Shorter Latin Primer, 1962 edition, pp. 91-2.)

- i.e. Proposita quae referenda sunt popolo, "Proposals which must be carried back to the people"

- Barber, Benjamin R.. The Death of Communal Liberty: A History of Freedom in a Swiss Mountain Canton. Princeton University Press, 1974, p. 179.

- Vincent, J.M.. State and Federal Government in Switzerland, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009, p. 122

- de Vreese, Claes H. (2007). "Context, Elites, Media and Public Opinion in Reerendums: When Campaigns Really Matter". The Dynamics of Referendum Campaigns: An International Perspective. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 2–3. ISBN 9780230591189.

- Serdült, Uwe; Welp, Yanina (2012). "Direct Democracy Upside Down" (PDF). Taiwan Journal of Democracy. 8 (1): 69–92. doi:10.5167/uzh-98412.

- "Design and Political issues of Referendums —". aceproject.org. Retrieved 2020-06-11.

- "Statewide bond propositions (California)". Ballotpedia. Retrieved 2020-06-11.

- Goetschel, Laurent; Bernath, Magdalena; Schwarz, Daniel (2004). Swiss Foreign Policy: Foundations and Possibilities. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-34812-6.

- "Recall of Local Officials". www.ncsl.org. Retrieved 2020-06-12.

- (in French) Bruno S. Frey et Claudia Frey Marti, Le bonheur. L'approche économique, Presses polytechniques et universitaires romandes, 2013 (ISBN 978-2-88915-010-6).

- Duc-Quang Nguyen (17 June 2015). "How direct democracy has grown over the decades". Berne, Switzerland: swissinfo.ch - a branch of the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation SRG SSR. Retrieved 2016-01-28.

- "Dipartimento per gli Affari Interni e Territoriali".

- "Manner in which referenda are held". Citizens' Assembly. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- Qvortrup, Matt (2013). Direct Democracy: A Comparative Study of the Theory and Practice of Government by the People. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-8206-1.

- Sottilotta, Cecilia Emma (2017). "The Strategic Use of Government-Sponsored Referendums in Contemporary Europe: Issues and Implications". Journal of Contemporary European Research. 13 (4): 1361–1376.

- Bowcott, Owen; Davies, Caroline (2019-12-31). "Referendums are a bad idea, Irish leader told EU in 1995". The Guardian.

- "California: The ungovernable state". The Economist. London. 16–22 May 2009. pp. 33–36.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Referendums. |

- Morel, L. (2011). 'Referenda'. In: B. Badie, D. Berg-Schlosser, & L. Morlino(eds), International Encyclopedia of Political Science.Thousand Oaks: SAGE: 2226-2230.

- Qvortrup, Matt (2017). "Demystifying Direct Democracy". Journal of Democracy. 28 (3): 141–152. doi:10.1353/jod.2017.0052.

- Qvortrup, Matt; O'Leary, Brendan; Wintrobe, Ronald (2018). "Explaining the Paradox of Plebiscites". Government and Opposition: 1–18. doi:10.1017/gov.2018.16.

- Setälä, M. (1999). Referendums and democratic government. London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Topaloff, Liubomir (2017). "Elite Strategy or Populist Weapon?". Journal of Democracy. 28 (3): 127–140. doi:10.1353/jod.2017.0051.