La patrie en danger

La patrie en danger (French: "The country (fatherland) in danger") was the start of a declaration by the French Assembly on 11 July 1792 in response to Prussia joining Austria against France. Along with the Levée en masse declared the next year, it was part of the growing idea of "people's war" which developed during the French Revolution, where ideology "not only conscripted manpower for the regular armies, but also inspired ordinary people to fight on their own account."[1]

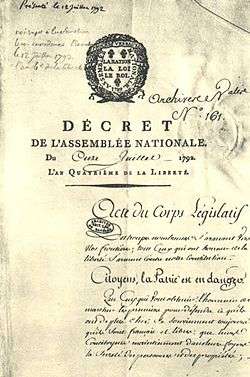

The text of the declaration reads:

- "Citoyens, la Patrie est en danger.

- "Que ceux qui vont obtenir l'honneur de marcher les premiers pour défendre ce qu'ils ont de plus cher se souviennent toujours qu'ils sont Français et libres; que leurs concitoyens la de maintiennent dans leur foyer la sûreté des personnes et des propriétés; que les magistrats du peuple veillent attentivement; que tous, dans un courage calme, attribut de la véritable force, attendent pour agir le signal de la loi, et la patrie sera sauvée."[2]

The phrase was taken up in other contexts, and became rather over-used. In French and sometimes other languages it has become proverbial, mostly used sarcastically.

Effects

According to Albert Soboul, the announcement of the fatherland in danger led to the unification of citizens at a time when their interests were jeopardized and intensified their participation both in political life and in military events.[3] The text of the declaration was read on the streets of French cities and villages. In Paris alone, 15 thousand volunteers enrolled in the army, or about 2.5% of the population.[4][5]

Along with the mass levy announced in 1793, this declaration became a stage in the development of the ideas of a “people's war” and an “armed nation” developed during the French Revolution.[6] The ideology of the people's war was “not only to mobilize human resources for regular armies, but also to inspire ordinary people to fight at their own expense”.[7]

At the same time, the success of the declaration of 1792 was closely linked with the then prevailing revolutionary moods in French society. In 1799, an attempt to adopt a similar declaration in the face of military defeats in the War of the Second Coalition did not end there. As F. Wartell observes, seven years later, “the spirit of 1792 was already dead”.[4]

See also

Bibliography

- Soboul, Albert (1975). The French Revolution 1787–1799. New York: Vintage. ISBN 0-394-71220-X.

- Tulard, Jean; Fayard, Jean-François; Fierro, Alfred (2002). "Patrie en Danger". Histoire et dictionnaire de la Révolution française. 1789—1799. P.: Éditions Robert Laffont. p. 1023. ISBN 978-2-2210-8850-0.

- Wartelle, F. (2014). "«Patrie en Danger»". Dictionnaire historique de la Révolution française. P.: Quadrige. Soboul, Albert (dir.). p. 825. ISBN 978-2-13-053605-5.

References

- Townshend, Charles. The Oxford History of Modern War. p. 177 ISBN 0-19-280645-9

- Antoine-François Bertrand de Moleville. Histoire de la revolution de France, pendant les dernières années du règne de Louis XVI. p. 293.

- Soboul 1975, p. 247.

- Wartelle 2014, p. 825.

- Tulard, Fayard & Fierro 2002, p. 1023.

- Forrest Alan (2000). "The Nation in Arms I: The French Wars". The Oxford History of Modern War. Oxford University Press. Townshend C. (ed.). pp. 55–73.

- Townshend C (2000). "People's War". The Oxford History of Modern War. Oxford University Press. Townshend C. (ed.). pp. 177–200.