French Guiana

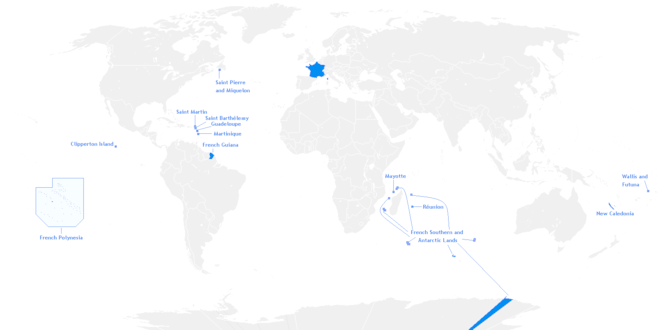

French Guiana (/ɡiˈɑːnə/ or /ɡiˈænə/; French: Guyane [ɡɥijan]) is an overseas department and region of France on the northern Atlantic coast of South America in the Guianas. It borders Brazil to the east and south and Suriname to the west. French Guiana is the only territory of the mainland Americas to have full integration in a European country.

Department of French Guiana Département de la Guyane | |

|---|---|

Ilet la Mère | |

| Motto(s): Equality, Unity, Fraternity | |

| |

| Coordinates: 4°N 53°W | |

| Country | |

| Prefecture | Cayenne |

| Departments | 1 (all overseas regions consist of a department in themselves.) |

| Government | |

| • President of the Assembly | Rodolphe Alexandre (PSG) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 83,534 km2 (32,253 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 2nd region and 1st department |

| Population (January 2020)[1] | |

| • Total | 290,691 |

| • Density | 3.5/km2 (9.0/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | French Guianese or Guianan |

| Time zone | UTC-03:00 (GFT) |

| ISO 3166 code | |

| GDP (2017)[2] | Ranked 17th |

| Total | €4.6 billion (US$5.2 bn) |

| Per capita | €16,200 (US$18,300) |

| NUTS Region | FRA |

| Website | Territorial Collectivity Prefecture |

With a land area of 83,534 km2 (32,253 sq mi), French Guiana is the second-largest region of France (it is more than one-seventh the size of Metropolitan France) and the largest outermost region within the European Union. It has a very low population density, with only 3.5 inhabitants per square kilometre (9.1/sq mi). (Its population is less than 1⁄200 that of Metropolitan France.) Half of its 290,691 inhabitants in 2020 lived in the metropolitan area of Cayenne, its capital. 98.9% of the land territory of French Guiana is covered by forests,[3] a large part of which is primeval rainforest. The Guiana Amazonian Park, which is the largest national park in the European Union,[4] covers 41% of French Guiana's territory.

Since December 2015 both the region and the department have been ruled by a single assembly within the framework of a new territorial collectivity, the French Guiana Territorial Collectivity (French: collectivité territoriale de Guyane). This assembly, the French Guiana Assembly (French: assemblée de Guyane), has replaced the former regional council and departmental council, which were both disbanded. The French Guiana Assembly is in charge of regional and departmental government. Its president is Rodolphe Alexandre.

Before European contact, the territory was originally inhabited by Native Americans, most speaking the Arawak language, of the Arawakan language family. The people identified as Lokono. The first French establishment is recorded in 1503, but France did not establish a durable presence until colonists founded Cayenne in 1643. Guiana was developed as a slave society, where planters imported Africans as enslaved labourers on large sugar and other plantations in such number as to increase the population. Slavery was abolished in the colonies at the time of the French Revolution. Guiana was designated as a French department in 1797. But, after France gave up most of its territory in North America in 1803, it developed Guiana as a penal colony, establishing a network of camps and penitentiaries along the coast where prisoners from metropolitan France were sentenced to forced labour.

During World War II and the fall of France to Nazi German forces, Félix Éboué was one of the first to support General Charles de Gaulle of Free France, as early as June 18, 1940. Guiana officially rallied to Free France in 1943. It abandoned its status as a colony and once again became a French department in 1946.

After de Gaulle was elected as president of France, he established the Guiana Space Centre in 1965. It is now operated by the CNES, Arianespace and the European Space Agency (ESA).

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, several hundred Hmong refugees from Laos immigrated to French Guiana, fleeing displacement after the communist takeover of Laos by Pathet Lao in 1975.[5] In the late 1980s, more than 10,000 Surinamese refugees, mostly Maroons, arrived in French Guiana, fleeing the Surinamese Civil War.[5] More recently, French Guiana has received large numbers of Brazilian and Haitian economic migrants.[5] Illegal and ecologically destructive gold mining by Brazilian garimpeiros is a chronic issue in the remote interior rain forest of French Guiana.[6][7] The region still faces such problems as illegal immigration, poorer infrastructure than mainland France, higher costs of living, higher levels of crime and more common social unrest.[8]

Fully integrated in the French central state in the 21st century, French Guiana is a part of the European Union, and its official currency is the euro. The region has the highest nominal GDP per capita in South America.[2] A large part of French Guiana's economy derives from jobs and businesses associated with the presence of the Guiana Space Centre, now the European Space Agency's primary launch site near the equator. As elsewhere in France, the official language is standard French, but each ethnic community has its own language, of which French Guianese Creole, a French-based creole language, is the most widely spoken.

Name

The addition of the adjective "French" in most languages other than French is rooted in colonial times, when five such colonies (The Guianas) had been named along the coast, subject to differing powers: namely (from west to east) Spanish Guiana (now Guayana Region and Guayana Esequiba in Venezuela), British Guiana (now Guyana), Dutch Guiana (now Suriname), French Guiana, and Portuguese Guiana (now Amapá in Brazil). French Guiana and the two larger countries to the north and west, Guyana and Suriname, are still often collectively referred to as "the Guianas" and constitute one large landmass known as the Guiana Shield.

History

French Guiana was originally inhabited by indigenous people: Kalina, Arawak, Galibi, Palikur, Teko, Wayampi and Wayana. The French attempted to create a colony there in the 18th century in conjunction with its settlement of some Caribbean islands, such as Guadeloupe and Saint-Domingue.

During the Revolution, the National Convention voted to abolish slavery in February 1794, months after the rebelling slaves had already announced an abolition of slavery in Saint-Domingue. However, the 1794 decree was only implemented in Saint-Domingue, Guadeloupe and Guyane: it was a dead letter in Senegal, Mauritius and Reunion. Martinique had been conquered by the British, who maintained slavery there.[9]

Bill Marshall, Professor of Comparative Cultural Studies at the University of Stirling[10] wrote of French Guiana's origins:

The first French effort to colonize Guiana, in 1763, failed utterly, as settlers were subject to high mortality given the numerous tropical diseases and harsh climate: all but 2,000 of the initial 12,000 settlers died. During operations as a penal colony beginning in the mid-19th century, France transported approximately 56,000 prisoners to Devil's Island. Fewer than 10% survived their sentence.[11]

Île du Diable (Devil's Island) was the site of a small prison facility, part of a larger penal system by the same name, which consisted of prisons on three islands and three larger prisons on the mainland. This was operated from 1852 to 1953.

%2C_Acervo_do_Museu_Paulista_da_USP_(cropped).jpg)

In addition, in the late nineteenth century, France began requiring forced residencies by prisoners who survived their hard labour.[12] A Portuguese-British naval squadron took French Guiana for the Portuguese Empire in 1809. It was returned to France with the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1814. Though Portugal returned the region to France, it kept a military presence until 1817.

After French Guiana had been established as a penal colony, officials sometimes used convicts to catch butterflies. The sentences of the convicts were often long, and the prospect of employment very weak, so the convicts caught butterflies to sell in the international market, both for scientific purposes as well as general collecting.[13]

A border dispute with Brazil arose in the late 19th century over a vast area of jungle, resulting in the short-lived, pro-French, independent state of Counani in the disputed territory. There was some fighting among settlers. The dispute was resolved largely in favour of Brazil by the arbitration of the Swiss government.[14]

The territory of Inini consisted of most of the interior of French Guiana when it was created in 1930. It was abolished in 1946, the year that French Guiana as a whole was formally established as an overseas department of France. During the 1970s, following the French withdrawal from Vietnam in the 1950s and warfare conducted in the region by the United States, France helped resettle thousands of Hmong refugees from Laos to French Guiana.

In 1964, French president Charles de Gaulle decided to construct a space-travel base in French Guiana. It was intended to replace the Sahara base in Algeria and stimulate economic growth in French Guiana. The department was considered particularly suitable for the purpose because it is near the equator and has extensive access to the ocean as a buffer zone. The Guiana Space Centre, located a short distance along the coast from Kourou, has grown considerably since the initial launches of the Véronique rockets. It is now part of the European space industry and has had commercial success with such launches as the Ariane 4 and Ariane 5.

The Guianese General Council officially adopted a departmental flag in 2010.[15] In a referendum that same year, French Guiana voted against autonomy.[16]

On March 20, 2017, French Guianese workers began going on strike and demonstrating for more resources and infrastructure.[17] March 28, 2017 was the day of the largest demonstration ever held in French Guiana.[18]

French Guiana has been impacted severely by the COVID-19 outbreak, with more than 1% of French Guianese testing positive by the end of June 2020.[19]

Geography

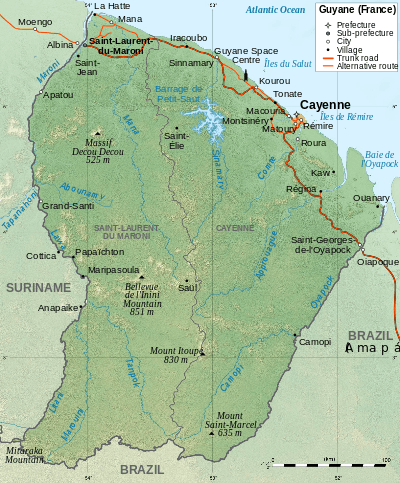

French Guiana lies between latitudes 3° and 6° N, and longitudes 51° and 55° W. It consists of two main geographical regions: a coastal strip where the majority of the people live, and dense, near-inaccessible rainforest which gradually rises to the modest peaks of the Tumuc-Humac mountains along the Brazilian frontier. French Guiana's highest peak is Bellevue de l'Inini in Maripasoula (851 m, 2,792 ft). Other mountains include Mont Machalou (782 m, 2,566 ft), Pic Coudreau (711 m, 2,333 ft), Mont St Marcel (635 m, 2,083 ft), Mont Favard (200 m, 660 ft) and Montagne du Mahury (156 m, 512 ft).

Several small islands are found off the coast, the three Salvation's Islands which include Devil's Island, and the isolated Îles du Connétable bird sanctuary further along the coast towards Brazil.

The Petit-Saut Dam, a hydroelectric dam in the north of French Guiana forms an artificial lake and provides hydroelectricity. There are many rivers in French Guiana, including the Waki River.

As of 2007, the Amazonian forest, located in the most remote part of the department, is protected as the Guiana Amazonian Park, one of the ten national parks of France. The territory of the park covers some 33,900 km2 (13,090 sq mi) upon the communes of Camopi, Maripasoula, Papaïchton, Saint-Élie and Saül.

Climate

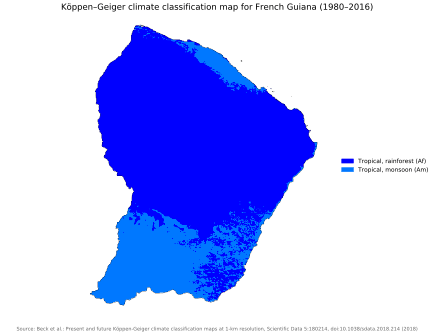

French Guiana has a tropical rainforest climate predominant.[20] Located within six degrees of the Equator and rising only to modest elevations, French Guiana is hot and oppressively humid all year round. During most of the year, rainfall across the country is heavy due to the presence of the Intertropical Convergence Zone and its powerful thunderstorm cells. In most parts of French Guiana, rainfall is always heavy especially from December to June or July – typically over 330 millimetres or 13 inches can be expected each month during this period throughout the department. Between August and November, the eastern half experiences a "dry" season with as little as 30 millimetres or 1.18 inches in September and October, causing eastern French Guiana to be classed as a tropical monsoon climate (Köppen Am); Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni in the west has a tropical rainforest climate (Af).

| Climate data for Cayenne, French Guiana | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 32 (90) |

34 (93) |

33 (91) |

33 (91) |

33 (91) |

34 (93) |

34 (93) |

36 (97) |

36 (97) |

36 (97) |

35 (95) |

34 (93) |

36 (97) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 27 (81) |

28 (82) |

28 (82) |

28 (82) |

28 (82) |

28 (82) |

29 (84) |

30 (86) |

31 (88) |

30 (86) |

30 (86) |

28 (82) |

29 (84) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 23 (73) |

23 (73) |

23 (73) |

23 (73) |

23 (73) |

23 (73) |

23 (73) |

22 (72) |

22 (72) |

22 (72) |

22 (72) |

23 (73) |

23 (73) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 19 (66) |

20 (68) |

19 (66) |

18 (64) |

20 (68) |

21 (70) |

20 (68) |

20 (68) |

21 (70) |

20 (68) |

20 (68) |

20 (68) |

18 (64) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 380 (15.0) |

320 (12.6) |

380 (15.0) |

380 (15.0) |

510 (20.1) |

390 (15.4) |

200 (7.9) |

100 (3.9) |

40 (1.6) |

50 (2.0) |

120 (4.7) |

290 (11.4) |

3,160 (124.6) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 20 | 16 | 22 | 21 | 26 | 23 | 18 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 11 | 18 | 192 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 82 | 80 | 82 | 84 | 85 | 82 | 78 | 74 | 71 | 71 | 76 | 81 | 79 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 155 | 113 | 124 | 120 | 124 | 180 | 217 | 248 | 270 | 279 | 240 | 186 | 2,256 |

| Source: BBC Weather[21] | |||||||||||||

Environment

French Guiana is home to many different ecosystems: tropical rainforests, coastal mangroves, savannahs, inselbergs and many types of wetlands. French Guiana has a high level of biodiversity of both flora and fauna. This is due to the presence of old-growth forests (i.e., ancient/primary forests), which are biodiversity hotspots. The rainforests of French Guiana provide shelter for many species during dry periods and terrestrial glaciation. These forests are protected by a national park (the Guiana Amazonian Park), and six additional nature reserves. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the European Union (EU) have recommended special efforts to protect these areas.[22]

Following the Grenelle Environment Round Table of 2007, the Grenelle Law II was proposed in 2009, under law number 2010–788. Article 49 of the law proposed the creation of a single organization responsible for environmental conservation in French Guiana. Article 64 proposes a "departmental plan of mining orientation" for French Guiana, which would promote mining (specifically of gold) that is compatible with requirements for environmental protection.[23] The coastal environment along the N1 has historically experienced the most changes, but development is occurring locally along the N2, and also in western French Guiana due to gold mining.

5,500 plant species have been recorded, including more than a thousand trees, along with 700 species of birds, 177 species of mammals, over 500 species of fish including 45% of which are endemic and 109 species of amphibians. The micro-organisms would be much more numerous, especially in the north, which competes with the Brazilian Amazon, Borneo and Sumatra. This single French department has at least 98% of vertebrate fauna and 96% of vascular plants as found in all of France and its overseas territories.

Threats to the ecosystem are: habitat fragmentation from roads, which remains very limited compared to other forests of South America; immediate and deferred impacts of EDF's Petit-Saut Dam; gold mining; poor control of hunting and poaching, facilitated by the creation of many tracks; and the introduction of all-terrain vehicles. Logging remains moderate due to the lack of roads, difficult climate, and difficult terrain. The Forest Code of French Guiana was modified by ordinance on 28 July 2005. Logging concessions or free transfers are sometimes granted by local authorities to persons traditionally deriving their livelihood from the forest.

The beaches of the natural reserve of the Amana, the joint Awala-Yalimapo in the west, is an exceptional marine turtle nesting site. This is one of the largest worldwide for the leatherback turtle.

Agriculture

French Guiana has some of the poorest soils in the world. The soil is low in nutrients (e.g., nitrogen, potassium) and organic matter. Soil acidity is another cause of the poor soils, and it requires farmers to add lime to their fields. All of these soil characteristics have led to the use of slash and burn agriculture. The resulting ashes elevate soil pH (i.e., lower soil acidity), and contribute minerals and other nutrients to the soil. Sites of Terra preta (anthropogenic soils) have been discovered in French Guiana, particularly near the border with Brazil. Research is being actively pursued in multiple fields to determine how these enriched soils were historically created, and how this can be done in modern times.

Economy

As a part of France, French Guiana is part of the European Union and the Eurozone; its currency is the euro. The country code top-level domain (ccTLD) for French Guiana is .gf, but .fr is generally used instead.[24]

In 2017, the GDP of French Guiana at market exchange rates was US$5.18 billion (€4.59 billion),[2] ranking as the largest economy in the Guianas, and the 11th largest in South America.[25]

French Guiana is heavily dependent on mainland France for subsidies, trade, and goods. The main traditional industries are fishing (accounting for 5% of exports in 2012), gold mining (accounting for 32% of exports in 2012) and timber (accounting for 1% of exports in 2012).[26] In addition, the Guiana Space Centre has played a significant role in the local economy since it was established in Kourou in 1964: it accounted directly and indirectly for 16% of French Guiana's GDP in 2002 (down from 26% in 1994, as the French Guianese economy is becoming increasingly diversified).[27] The Guiana Space Centre employed 1,659 people in 2012.[28]

There is very little manufacturing. Agriculture is largely undeveloped and is mainly confined to the area near the coast and along the Maroni River. Sugar and bananas were traditionally two of the main cash crops grown for export but have almost completely disappeared. Today they have been replaced by livestock raising (essentially beef cattle and pigs) in the coastal savannas between Cayenne and the second-largest town, Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni, and market gardening (fruits and vegetables) developed by the Hmong communities settled in French Guiana in the 1970s, both destined to the local market. A thriving rice production, developed on polders near Mana from the early 1980s to the late 2000s, has almost completely disappeared since 2011 due to marine erosion and new EU plant health rules which forbid the use of many pesticides and fertilizers. Tourism, especially eco-tourism, is growing. Unemployment has been persistently high in the last few decades: 20% to 25% (22.3% in 2012).[29]

In 2017, the GDP per capita of French Guiana at market exchange rates, not at PPP, was US$18,313 (€16,218),[2] the highest in South America,[30] but only 46.7% of metropolitan France's average GDP per capita that year, and 55.5% of the metropolitan French regions outside the Paris Region.[2] Social unrest in 2017 paralyzed the economy for several weeks and led to an economic recession (−1.9% in real terms), which sunk the GDP per capita that year.[31]

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal GDP (€ bn) | 4.44 | 4.69 | 4.59 |

| GDP per capita (euros) | 16,784 | 17,139 | 16,218 |

| GDP per capita as a % of Metropolitan France's | 50.2 | 50.7 | 46.7 |

| Sources: Eurostat;[2] INSEE for the population.[1] | |||

Demographics

| 1790 estimate | 1839 estimate | 1857 estimate | 1891 estimate | 1936 census | 1946 census | 1952 estimate | 1954 census | 1961 census |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14,520 | 20,940 | 25,561 | 33,500 | 37,005 | 28,506 | 25,459 | 27,863 | 33,505 |

| 1967 census | 1974 census | 1982 census | 1990 census | 1999 census | 2007 census | 2012 census | 2017 census | 2020 estimate |

| 44,392 | 55,125 | 73,022 | 114,678 | 156,790 | 213,031 | 239,648 | 268,700 | 290,691 |

| Official figures from past censuses and INSEE estimates. | ||||||||

French Guiana's population of 290,691 (2020 estimate[1]), most of whom live along the coast, is substantially ethnically diverse. At the 2014 census, 57.3% of the inhabitants of French Guiana were born in French Guiana, 9.3% were born in Metropolitan France, 3.0% were born in the French Caribbean departments and collectivities (Guadeloupe, Martinique, Saint Martin, Saint Barthélemy), and 30.2% were born in foreign countries (primarily Suriname, Brazil and Haiti).[32]

Estimates of the percentages of French Guiana ethnic composition are difficult to produce due to the presence of a large proportion of immigrants. People of mixed African and French ancestry are the largest ethnic group, though estimates vary as to the exact percentage, depending upon whether the large Haitian community is included as well. Generally, the Creole population is judged to be about 60–70% of the total population if Haitians (comprising roughly one-third of Creoles) are included, and 30–50% otherwise. There are also smaller groups from various Caribbean islands, mainly Martinique, Guadeloupe, Saint Lucia as well as Dominica.

Roughly 14% of the population is of European ancestry. The vast majority of these are of French ancestry, though there are also people of Dutch, British, Spanish and Portuguese ancestry.

The main Asian communities are the Chinese (about 3–4%, primarily from Zhejiang Province and Guangdong Province in mainland China) and Hmong from Laos (1–2%). Other groups from Asia include East Indians, Lebanese and Vietnamese.

The main groups living in the interior are the Maroons who are of African descent, and Amerindians. The Maroons, descendants of escaped African slaves, live primarily along the Maroni River. The main Maroon groups are the Saramaca, Aucan (both of whom also live in Suriname), and Boni (Aluku).

The main Amerindian groups (forming about 3–4% of the population) are the Arawak, Carib, Emerillon (now called the Teko), Galibi (now called the Kaliña), Palikur, Wayampi and Wayana. As of the late 1990s, there was evidence of an uncontacted group of Wayampi.

Immigration

| Census | Born in French Guiana | Born in Metropolitan France | Born in the French West Indies | Born in the rest of Overseas France | Born in foreign countries with French citizenship at birth¹ | Immigrants² |

| 2014 | 57.3% | 9.3% | 3.0% | 0.3% | 1.2% | 29.0% |

| 2011 | 56.5% | 9.3% | 3.4% | 0.2% | 1.3% | 29.3% |

| 2006 | 55.3% | 9.6% | 3.1% | 0.2% | 1.4% | 30.4% |

| 1999 | 54.4% | 11.8% | 4.9% | 0.3% | 2.0% | 26.6% |

| 1990 | 50.5% | 11.7% | 5.2% | 0.3% | 1.9% | 30.4% |

| ¹Persons born abroad of French parents, such as Pieds-Noirs and children of French expatriates. ²An immigrant is by French definition a person born in a foreign country and who didn't have French citizenship at birth. Note that an immigrant may have acquired French citizenship since moving to France, but is still listed as an immigrant in French statistics. On the other hand, persons born in France with foreign citizenship (the children of immigrants) are not listed as immigrants. | ||||||

| Source: INSEE[32] | ||||||

Religion

The dominant religion of French Guiana is Roman Catholicism; the Maroons and some Amerindian peoples maintain their own religions. The Hmong people are also largely Catholic owing to the influence of missionaries who helped bring them to French Guiana.[33] Guianan Catholics are part of the Diocese of Cayenne.

Fertility

The total fertility rate in French Guiana has remained high and is today considerably higher than that of metropolitan France, as well as most of the other French overseas departments. It is largely responsible for the rapid population growth of French Guiana.

| 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| French Guiana | 3.87 | 3.93 | 3.79 | 3.73 | 3.77 | 3.47 | 3.79 | 3.80 | 3.73 | 3.57 | 3.49 | 3.37 | 3.42 | 3.60 | 3.47 | 3.44 | 3.44 | 3.61 | 3.93 | 3.82 |

| 4 overseas departmentsA | 2.32 | 2.45 | 2.42 | 2.35 | 2.38 | 2.40 | 2.46 | 2.48 | 2.48 | 2.46 | 2.42 | 2.39 | 2.40 | 2.48 | 2.44 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Metropolitan France | 1.79 | 1.87 | 1.88 | 1.86 | 1.87 | 1.90 | 1.92 | 1.98 | 1.96 | 1.99 | 1.99 | 2.02 | 2.00 | 1.99 | 1.97 | 1.97 | 1.93 | 1.89 | 1.86 | 1.84 |

| Source: INSEE[34] A Data for the four overseas departments of French Guiana, Martinique, Guadeloupe, and Réunion, not including the new overseas department of Mayotte. | ||||||||||||||||||||

Languages

The official language of French Guiana is French, and it is the predominant language of the department, spoken by most residents as a first or second language. In addition, a number of other local languages exist. Regional languages include French Guianese Creole (not to be confused with Guyanese Creole), six Amerindian languages (Arawak, Palijur, Kali'na, Wayana, Wayampi, Emerillon), four Maroon creole languages (Saramaka, Paramaccan, Aluku, Ndyuka), as well as Hmong Njua.[35] Other languages spoken include Portuguese, Hakka, Haitian Creole, Spanish, Dutch, English, and Tamil, and Caribbean Hindustani.

Politics

French Guiana, as part of France, forms part of the European Union – the largest landmass for an area outside of Europe (since Greenland left the European Community in 1985), with one of the longest EU external boundaries. It is one of only three European Union territories outside Europe that is not an island (the others being the Spanish Autonomous Cities in Africa, Ceuta and Melilla). As an integral part of France, its head of state is the President of the French Republic, and its head of government is the Prime Minister of France. The French Government and its agencies have responsibility for a wide range of issues that are reserved to the national executive power, such as defense and external relations.

The President of France appoints a prefect (resident at the prefecture building in Cayenne) as his representative to head the local government of French Guiana. There is one elected, local executive body, the Assemblée de Guyane.[36]

French Guiana sends two deputies to the French National Assembly, one representing the commune (municipality) of Cayenne and the commune of Macouria, and the other representing the rest of French Guiana. This latter constituency is the largest in the French Republic by land area. French Guiana also sends two senators to the French Senate.

The Guianese Socialist Party dominated politics in French Guiana until 2010.

A chronic issue affecting French Guiana is the influx of illegal immigrants and clandestine gold prospectors from Brazil and Suriname. The border between the department and Suriname, the Maroni River, flows through rain forest and is difficult for the Gendarmerie and the French Foreign Legion to patrol. There have been several phases launched by the French government to combat illegal gold mining in French Guiana, beginning with Operation Anaconda beginning in 2003, followed by Operation Harpie in 2008, 2009 and Operation Harpie Reinforce in 2010. Colonel François Müller, the commander of French Guiana's gendarmes, believes these operations have been successful. However, after each operation ends, Brazilian miners, garimpeiros, return.[37] Soon after Operation Harpie Reinforce began, an altercation took place between French authorities and Brazilian miners. On 12 March 2010 a team of French soldiers and border police were attacked while returning from a successful operation, during which "the soldiers had arrested 15 miners, confiscated three boats, and seized 617 grams of gold... currently worth about $22,317". Garimpeiros returned to retrieve their lost loot and colleagues. The soldiers fired warning shots and rubber "flash balls", but the miners managed to retake one of their boats and about 500 grams of gold. "The violent reaction by the garimpeiros can be explained by the exceptional take of 617 grams of gold, about 20 percent of the quantity seized in 2009 during the battle against illegal mining", said Phillipe Duporge, the director of French Guiana's border police, at a press conference the next day.[38]

Transport

French Guiana's main international airport is Cayenne – Félix Eboué Airport, located in the commune of Matoury, a southern suburb of Cayenne. There are two flights a day to Paris (Orly Airport), served by Air France and Air Caraïbes. The flight time from Cayenne to Paris is 8 hours and 10 minutes, and from Paris to Cayenne it is 8 hours and 30 minutes. There are also flights to Fort-de-France, Pointe-à-Pitre, Belém, and Fortaleza.

French Guiana's main seaport is the port of Dégrad des Cannes, located on the estuary of the Mahury River, in the commune of Remire-Montjoly, a south-eastern suburb of Cayenne. Almost all of French Guiana's imports and exports pass through the port of Dégrad des Cannes. Built in 1969, it replaced the old harbour of Cayenne which was congested and could not cope with modern traffic.

An asphalted road from Régina to Saint-Georges de l'Oyapock (a town by the Brazilian border) was opened in 2004, completing the road from Cayenne to the Brazilian border. It is now possible to drive on a fully paved road from Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni on the Surinamese border to Saint-Georges de l'Oyapock on the Brazilian border.

Following a treaty between France and Brazil signed in July 2005, the Oyapock River Bridge over the Oyapock River was built and completed in 2011, becoming the first land crossing ever between French Guiana and the rest of the world (there exists no other bridge crossing the Oyapock River, and no bridge crossing the Maroni River marking the border with Suriname, although there is a ferry crossing to Albina, Suriname). The bridge was officially opened on March 18, 2017. However, since the Brazilian government is yet to complete its border posts, only passenger vehicles will be allowed through the bridge for the time being.[39] The inauguration makes it possible to drive uninterrupted from Cayenne to Macapá, the capital of the state of Amapá in Brazil.

Main settlements

Population figures are those recorded in the 2017 census.[40]

- Cayenne: 61,268 inhabitants in the commune; 118,346 inhabitants in the urban area (which includes the communes of Cayenne, Matoury, and Remire-Montjoly); 138,920 in the metropolitan area (which additionally includes the communes of Macouria, Montsinéry-Tonnegrande, and Roura)

- Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni: 42,612

- Kourou: 25,685

- Maripasoula: 13,227

- Mana: 10,894

- Apatou: 9,241

- Grand-Santi: 7,918

- Papaïchton: 6,668

- Saint-Georges: 4,131

Military, police and security forces

The commander of the French armed forces in French Guiana since July 2009 has been General Jean-Pierre Hestin. The military there is currently 1,900 strong, expected to increase enrollment in 2014–2015.[41]

Among the military, police and security forces in French Guiana, are the following:

- The 3rd Foreign Infantry Regiment (3e REI) of Kourou (Legion).

- The 9th Marine Infantry Regiment (9e RIMa) of Cayenne, the Madeleine.

- The gendarmerie and the police, divided into 16 brigades. These serve Cayenne, Remire-Montjoly, Cacao, Régina, Saint-Georges-de-l'Oyapock, Camopi, Macouria, Kourou, Sinnamary, Iracoubo, Mana, Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni, Apatou, Grand-Santi, Papaïchton, Maripasoula and Matoury.

- The RSMAG Regiment (Adapted Military Service) of Guyana, located in Saint-Jean-du-Maroni, with a detachment in Cayenne.

- Various detachments corps:

- A French Air Force platoon based at the Felix Eboué airport.[42]

- The platoon of the French Navy, based at the naval base of Dégrad des Cannes.

- A detachment of the Paris Fire Brigade in Kourou, ensuring the protection of the Guiana Space Centre.

Culture and sport

At Easter, French Guianese people eat a traditional dish called Awara broth.

As a French Overseas department, French Guiana is not a member of the Pan American Sports Organization; rather, athletes compete within the French National Olympic and Sports Committee and are governed by the Ligue d'Athlétisme de la Guyane, a sub-unit of the Fédération française d'athlétisme.

The Ligue de Football de la Guyane is a member of CONCACAF but not of FIFA, and the French Guiana football team finished third in the 2017 Caribbean Cup. The French Guiana Honor Division is the main football club tournament.

Starting in 1960, the Tour of Guiana, an annual multiple stage bicycle race, is held.[43]

In popular culture

The novel Papillon, by the French convict Henri Charrière, is set in French Guiana. It was first published in France in 1969, describing his escape from a penal colony there. Becoming an instant bestseller, it was translated into English from the original French by June P. Wilson and Walter B. Michaels for a 1970 edition, and by author Patrick O'Brian. Soon afterward the book was adapted for a Hollywood film of the same name. Charrière stated that all events in the book are truthful and accurate, allowing for minor lapses in memory. Since its publication there has been controversy over its accuracy.[44][45]

Notable people

- Alicia Aylies

- Élie Castor

- Justin Catayée

- Léon Damas

- Lucie Décosse

- Félix Éboué

- Odsonne Édouard

- Léopold Héder

- Florent Malouda

- René Maran

- Malia Metella

- Gaston Monnerville

- Kevin Séraphin

- Gadwin Springer

- Christiane Taubira

- Jean-Clair Todibo

- Richard Sele

See also

- Index of French Guiana-related articles

- List of colonial and departmental heads of French Guiana

- Republic of Independent Guyana

References

- INSEE. "Estimation de population par région, sexe et grande classe d'âge – Années 1975 à 2020" (in French). Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- "Gross domestic product (GDP) at current market prices by NUTS 2 regions". Eurostat. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- "FAOSTAT – Land Use". Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- "Parc amazonien de Guyane, le plus vaste Parc national de France et de l'Union européenne". Guiana Amazonian Park. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- "Panorama de la population immigrée en Guyane" (PDF). INSEE. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- "Illegal, polluting and dangerous: the gold rush in French Guiana". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- "The fight against illegal gold mining in French Guiana". France 24. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- "Why one part of South America is facing a total shutdown". BBC News. 10 April 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- Sue Peabody, French Emancipation https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199730414/obo-9780199730414-0253.xml Accessed 27 October 2019.

- University of Stirling. "Stirling Research Database, Prof Bill Marshall".

- Marshall, Bill (2005). France and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, Inc. pp. 372–373. ISBN 1-85109-411-3.

- "French Guiana", Encyclopædia Britannica

- , Convicts, "Collecting and Knowledge Production in the Nineteenth Century", Clare Anderson, Staff Blogs

- Carlos A. Parodi (2002). The Politics of South American Boundaries. Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-275-97194-5.

- "The General Council adopts the Guyanese flag". 97320.com (in French). OuebTV. 26 January 2010. Archived from the original on 31 May 2017.

- Faget, Dominique (3 April 2017). "Cazeneuve calls for continuation of dialogue in French Guiana". Radio France International. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

In a referendum in January 2010, French Guiana voted firmly against autonomy.

- Marot, Laurent (27 March 2017). "La Guyane paralysée par les mouvements sociaux". Le Monde. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- "Guyane : manifestations historiques pour la "journée morte"". Le Point. 28 March 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- Thébia, Marie-Claude (29 June 2020). "Coronavirus : 3 décès en 48h, et 313 nouvelles contaminations indique le Covid info de ce lundi 29 juin". Guyane 1. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- "French Guiana Climate, Average Weather, Temperatures, Rainfall, Sunshine, Humidity, Graphs". www.french-guiana.climatemps.com. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- "Average Conditions Cayenne, French Guiana". BBC Weather. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- Comité français de l’Union Internationale pour la Conservation de la Nature (French Committee of the International Union for Conservation of Nature) (2003). "Guyane (Guyana)" (PDF). Biodiversité et conservation en outre-mer (Biodiversity and conservation overseas). Comité français de l’UICN (French Committee of the IUCN). Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- Borloo, Jean-Louis (12 January 2009). "Portant engagement national pour l'environnement (on national commitment to the environment)". Loi n° 2010-788 (law number 2010-788). Sénat français (French Senate). Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- French Guiana. CIA World Factbook (2004)

- International Monetary Fund. "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019 – Gross domestic product per capita, current prices, U.S. dollars". Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- IEDOM. "Guyane – Rapport annuel 2012" (PDF). p. 46. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- INSEE. "Le poids du spatial diminue, l'économie de la Guyane se diversifie" (PDF). Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- IEDOM. "Guyane – Rapport annuel 2012" (PDF). p. 136. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- INSEE. "T401 : Taux de chômage localisé au deuxième trimestre par département d'outre-mer". Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- International Monetary Fund. "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019 – Gross domestic product per capita, current prices, U.S. dollars". Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- CEROM. "Les comptes économiques de la Guyane en 2017" (PDF). Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- INSEE. "Données harmonisées des recensements de la population 1968–2014" (in French). Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- Palmerlee, Danny (2007). South America. Lonely Planet. ISBN 1-74104-443-X.

- INSEE. "P3D – Indicateurs généraux de la population par département et région – Séries depuis 1990" (in French). Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- "Ethnologue report for French Guiana". Ethnologue (16th ed.). 2009. Retrieved 22 September 2009.

- "Evolution institutionnelle La Collectivité Territoriale de Guyane". Archived from the original on 7 October 2015. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- Tabor, Damon (1 April 2010) French Guiana: Interview with Colonel Francois Müller, Commander of the Gendarmes. untoldstories.pulitzercenter.org

- Tabor, Damon (17 March 2010) French Guiana: Welcome to the Jungle. untoldstories.pulitzercenter.org

- "Ponte entre Brasil e União Europeia é aberta no Amapá após 6 anos pronta". Amapá (in Portuguese). 18 March 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- INSEE. "Historique des populations communales". Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- Journal of Guyana RFO TV 18 August 2009

- Aéroport. guyane.cci.fr

- "Comité Régional de Cyclisme de la Guyane". Guyane Cyclisme (in French). Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- If this is correct; the 'real' Papillon. Rue Rude. December 2005

- Randall, Colin (27 June 2005) Ex-convict aged 104 claims to be Papillon. Telegraph.co.uk

Further reading

- Robert Aldrich and John Connell. France's Overseas Frontier : Départements et territoires d'outre-mer Cambridge University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-521-03036-6.

- René Belbenoit. Dry guillotine: Fifteen years among the living dead 1938, Reprint: Berkley (1975). ISBN 0-425-02950-6.

- René Belbenoit. Hell on Trial 1940, translated from the original French manuscript by Preston Rambo. E. P Dutton & Co. Reprint by Blue Ribbon Books, New York, 194 p. Reprint: Bantam Books, 1971.

- Henri Charrière. Papillon Reprints: Hart-Davis, MacGibbon Ltd. 1970. ISBN 0-246-63987-3 (hbk); Perennial, 2001. ISBN 0-06-093479-4 (sbk).

- John Gimlette, Wild Coast: Travels on South America's Untamed Edge 2011

- Joshua R. Hyles (2013). Guiana and the Shadows of Empire: Colonial and Cultural Negotiations at the Edge of the World. Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739187807.

- Peter Redfield. Space in the Tropics: From Convicts to Rockets in French Guiana ISBN 0-520-21985-6.

- Miranda Frances Spieler. Empire and Underworld: Captivity in French Guiana (Harvard University Press; 2012) studies slaves, criminals, indentured workers, and other marginalized people from 1789 to 1870.

External links

- Worldover.com: French Guiana

- Consular Information Sheet from the United States Department of State

- Ethnologue French Guiana page

- Silvolab Guyanae – scientific interest group in French Guiana

- Article on separatism in French Guiana

- Status of Forests in French Guiana

- French Guiana Travel Guide, Good Addresses and Tips

- Officials reports, thesis, scientific papers about French Guiana (en|fr)

- Training legionnaires to fight in French Guiana

- The IRD's database AUBLET2 stores information about botanical specimens collected in the Guianas, mainly in French Guiana

- James Rogers and Luis Simón. The Status and Location of the Military Installations of the Member States of the European Union and Their Potential Role for the European Security and Defence Policy (ESDP). Brussels: European Parliament, 2009. 25 pp.

.jpg)

.svg.png)