Philippine Revolution

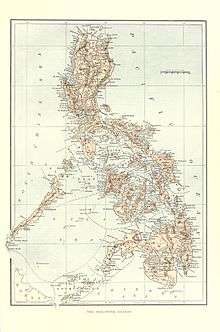

The Philippine Revolution (Filipino: Himagsikang Pilipino; Spanish: Revolución Filipina), called the Tagalog War (Filipino: Digmaang Tagalog; Spanish: Guerra Tagala) by the Spanish,[2] was a revolution and subsequent conflict fought between the people and insurgents of the Philippines and the Spanish colonial authorities of the Spanish East Indies, under the Spanish Empire (Kingdom of Spain).

| Philippine Revolution Himagsikang Pilipino | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

1896–1897

|

1896–1897 | ||||||

|

1898 | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Supremo: |

Queen Regent: Governor-Generals: (1896) (1896–1897) (1897–1898) (1898) (1898) (1898) Other leaders: | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 40,000–60,000 (1896) Filipino Revolutionaries | 12,700–17,700 before the Revolution, around 55,000 (30,000 Spanish; 25,000 Filipino Loyalists) by 1898 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Heavy; official casualties are unknown. | Heavy; official casualties are unknown. | ||||||

The Philippine Revolution began in August 1896, when the Spanish authorities discovered the Katipunan, an anti-colonial secret organization. The Katipunan, led by Andrés Bonifacio, began to influence much of the Philippines. During a mass gathering in Caloocan, the leaders of the Katipunan organized themselves into a revolutionary government, named the newly established government "Haring Bayang Katagalugan", and openly declared a nationwide armed revolution.[3] Bonifacio called for an attack on the capital city of Manila. This attack failed; however, the surrounding provinces began to revolt. In particular, rebels in Cavite led by Mariano Álvarez and Emilio Aguinaldo (who were from two different factions of the Katipunan) won early major victories. A power struggle among the revolutionaries led to Bonifacio's death in 1897, with command shifting to Aguinaldo, who led the newly formed revolutionary government. That year, the revolutionaries and the Spanish signed the Pact of Biak-na-Bato, which temporarily reduced hostilities. Aguinaldo and other Filipino officers exiled themselves in the British colony of Hong Kong in southern China. However, the hostilities never completely ceased.[4]

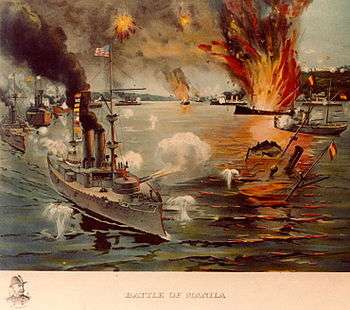

On April 21, 1898, after the sinking of USS Maine in Havana Harbor and prior to its declaration of war on April 25, the United States launched a naval blockade of the Spanish colony island of Cuba, off its southern coast of the peninsula of Florida. This was the first military action of the Spanish–American War of 1898.[5] On May 1, the U.S. Navy's Asiatic Squadron, under Commodore George Dewey, decisively defeated the Spanish Navy in the Battle of Manila Bay, effectively seizing control of Manila. On May 19, Aguinaldo, unofficially allied with the United States, returned to the Philippines and resumed attacks against the Spaniards. By June, the rebels had gained control of nearly all of the Philippines, with the exception of Manila. On June 12, Aguinaldo issued the Philippine Declaration of Independence.[6] Although this signified the end date of the revolution, neither Spain nor the United States recognized Philippine independence.[7]

The Spanish rule of the Philippines officially ended with the Treaty of Paris of 1898, which also ended the Spanish–American War. In the treaty, Spain ceded control of the Philippines and other territories to the United States.[4] There was an uneasy peace around Manila, with the American forces controlling the city and the weaker Philippines forces surrounding them.

On February 4, 1899, in the Battle of Manila, fighting broke out between the Filipino and American forces, beginning the Philippine–American War. Aguinaldo immediately ordered "[t]hat peace and friendly relations with the Americans be broken and that the latter be treated as enemies".[8] In June 1899, the nascent First Philippine Republic formally declared war against the United States.[9][10]

The Philippines would not become an internationally recognized independent state until 1946.

Summary

The main influx of revolutionary ideas came at the start of the 19th century, when the Philippines was opened for world trade. In 1809, the first English firms were established in Manila, followed by a royal decree in 1834 which officially opened the city to world trade. The Philippines had been governed from Mexico since 1565,[11] with colonial administrative costs sustained by subsidies from the galleon trade. Increased competition with foreign traders brought the galleon trade to an end in 1815. After its recognition of Mexican independence in 1821, Spain was forced to govern the Philippines directly from Madrid and to find new sources of revenue to pay for the colonial administration.[12] At this point, post-French Revolution ideas entered the country through literature, which resulted in the rise of an enlightened principalía class in the society.

The 1868 Spanish Revolution brought the autocratic rule of Queen Isabella II to an end. The autocratic government was replaced by a liberal government led by General Francisco Serrano.[13] In 1869, Serrano appointed Carlos María de la Torre as the 91st governor-general. The leadership of de la Torre introduced the idea of liberalism to the Philippines.

The election of Amadeo of Savoy to the throne of Spain led to the replacement of de la Torre in 1871.[14] In 1872, the government of the succeeding governor-general, Rafael de Izquierdo, experienced the uprising of Filipino soldiers at the Fort San Felipe arsenal in Cavite el Viejo. Seven days after the mutiny, many people were arrested and tried. Three of these were secular priests: José Burgos, Mariano Gómez and friar Jacinto Zamora, who were hanged by Spanish authorities in Bagumbayan.[15] Their execution had a profound effect on many Filipinos; José Rizal, the national hero, would dedicate his novel El filibusterismo to their memory.[16]

Many Filipinos who were arrested for possible rebellion were deported to Spanish penal colonies.[17] Some of them, however, managed to escape to Hong Kong, Yokohama, Singapore, Paris, London, Berlin, and some parts of Spain. These people met fellow Filipino students and other exiles who had escaped from penal colonies. Bound together by common fate, they established an organization known as the Propaganda Movement. These émigrés used their writings primarily to condemn Spanish abuses and seek reforms to the colonial government.

José Rizal's novels, Noli Me Tángere (Touch Me Not, 1887) and El Filibusterismo (The Filibuster, 1891), exposed Spanish abuses in socio-political and religious aspects. The publication of his first novel brought the infamous agrarian conflict in his hometown of Calamba, Laguna in 1888, when Dominican haciendas fell into trouble of submitting government taxes. In 1892, after his return from the Americas, Rizal established La Liga Filipina (The Filipino League), a Filipino association organized to seek reforms in the colonial government. When the Spaniards learned that Rizal was in the Philippines, they arrested and deported him a few days after the Liga was established.

Upon hearing that Rizal had been deported to Dapitan, Liga member Andrés Bonifacio and his fellows established a secret organization named Katipunan in a house located in Tondo, Manila, while more conservative members led by Domingo Franco and Numeriano Adriano would later establish the Cuerpo de Compromisarios. The Katipunan obtained overwhelming number of members and attracted the lowly classes. In June 1896, Bonifacio sent an emissary to Dapitan to obtain Rizal's support, but Rizal refused to participate in an armed revolution. On August 19, 1896, Katipunan was discovered by a Spanish friar, which resulted in the start of the Philippine Revolution.

The revolution initially flared up in the eight provinces of Central Luzon. The armed resistance eventually spread throughout the Southern Tagalog region, particularly in Cavite province, where towns were gradually liberated during the early months of the uprising. In 1896 and 1897, successive conventions at Imus and Tejeros decided the new republic's fate. In November 1897, the Republic of Biak-na-Bato was established and a constitution was promulgated by the insurgent government.

On May 1, 1898, the Battle of Manila Bay took place as part of the Spanish–American War. On May 24, Aguinaldo, who had returned from voluntary exile on May 19, announced in Cavite, "... I return to assume command of all the forces for the attainment of our lofty aspirations, establishing a dictatorial government which will set forth decrees under my sole responsibility, ..."[18] On 12 June, Aguinaldo proclaimed Philippine independence.[19] On 18 June, Aguinaldo issued a decree proclaiming a Dictatorial Government led by himself.[20] On June 23, Aguinaldo issued another decree, which replaced the Dictatorial Government with a Revolutionary Government.[21] In 1898, between June and September 10, the Malolos Congress elections were held by the Revolutionary Government, resulting in Emilio Aguinaldo being elected as President of the Philippines. On February 2, 1899, hostilities broke out between U.S. and Filipino forces.[22] The Malolos Constitution was adopted in a session convened on 15 September 1898. It was promulgated on 21 January 1899. creating the First Philippine Republic with Aguinaldo as President. On June 12, 1899, Aguinaldo promulgated a declaration of war against the U.S., beginning the Philippine–American War. U.S. forces captured Aguinaldo on March 23, 1901, and he swore allegiance to the U.S. on April 1. On July 4, 1902, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt proclaimed a complete pardon and amnesty for all Filipinos who had participated in the conflict, effectively ending the war.[23][24]

Origins

The Philippine Revolution was an accumulation of ideas and exposition to the international community, which led to the start of nationalistic endeavors. The rise of Filipino nationalism was slow, but inevitable. Abuses by the Spanish government, military and clergy prevalent during three centuries of colonial rule, and the exposure of these abuses by the "ilustrados" in the late 19th century, paved the way for a united Filipino people.[25][26] However, the growth of nationalism was slow because of the difficulty in social and economic intercourse among the Filipinos. In a dated letter written by the Filipino writer José P. Rizal to Father Vicente García of Ateneo Municipál de Manila, Rizal states that:[27]

There is, then, in the Philippines, a progress or improvement which is individual, but there is no national progress.

— January 17, 1891

Opening of Manila to world trade

Before the opening of Manila to foreign trade, the Spanish authorities discouraged foreign merchants from residing in the colony and engaging in business.[28] The royal decree of February 2, 1800, prohibited foreigners from living in the Philippines.[29] as did the royal decrees of 1807 and 1816.[29] In 1823, Governor-General Mariano Ricafort promulgated an edict prohibiting foreign merchants from engaging in retail trade and visiting the provinces for the purpose of trading. It was reissued by Lardizábal in 1840.[30] A royal decree issued in 1844 prohibited foreigners from traveling to the provinces under any pretext whatsoever, and in 1857, several anti-foreigner laws were renewed.[31]

With the wide acceptance of laissez-faire doctrines in the later part of the 18th century, Spain relaxed its mercantilist policies. The British occupation of Manila in 1762–1764 made Spain realize the impossibility of isolating the colony from world intercourse and commerce.[32] In 1789, foreign vessels were given permission to transport Asian goods to the port of Manila.[33] Even before the 1780s, many foreign ships, including Yankee clipper ships, had visited Manila regardless of anti-foreigner regulations. In 1790, Governor-General Félix Berenguer de Marquina recommended that the King of Spain open Manila to world commerce.[34] Furthermore, the bankruptcy of the Real Compaña de Filipinas (Royal Company of the Philippines) catapulted the Spanish king to open Manila to world trade. In a royal decree issued on September 6, 1834, the privileges of the company were revoked and the port of Manila was opened to trade.[35]

Economic surveys, port openings and admission of foreign firms

Shortly after the opening of Manila to world trade, the Spanish merchants began to lose their commercial supremacy in the Philippines. In 1834, restrictions against foreign traders were relaxed when Manila became an open port. By the end of 1859, there were 15 foreign firms in Manila. Seven of these were British, three were American, two were French, two were Swiss and one was German.[36]

In 1834, some American merchants settled in Manila and invested heavily in business. Two American business firms were established—the Russell, Sturgis & Company and the Peele, Hubbell & Company. These became two of the leading business firms. At first, Americans had an edge over their British competitors, because they offered good prices for Philippine exports like hemp, sugar, and tobacco.[37]

American trade supremacy did not last long. In the face of stiff British competition, they gradually lost control over Philippine business. This decline was due to lack of support from the U.S. government and lack of U.S. trade bases in the Orient.[37] In 1875, Russell, Sturgis & Company went into bankruptcy, followed by Peele, Hubbell & Company in 1887. Soon after, British merchants, including James Adam Smith, Lawrence H. Bell and Robert P. Wood, dominated the financial activities in Manila.[37]

In 1842, alarmed by the domination of the British and Americans in the economy of Manila, the Spanish government sent Sinibaldo de Mas, a Spanish diplomat, to the Philippines in order to conduct an economic survey of the Philippines and submit recommendations.[38] After an intensive investigation of colonial affairs in the Philippines, Mas submitted his official report to the Crown. The report, Informe sobre el estado de las Islas Filipinas en 1842, was published at Madrid in 1843. Mas recommended the following: opening of more ports to promote foreign trade, encouragement of Chinese immigration to stimulate agricultural development, and abolition of the tobacco monopoly.[39]

In response to Sinibaldo de Mas's recommendations, more ports were opened by Spain. The ports of Sual, Pangasinan, Iloilo and Zamboanga were opened in 1855, Cebu was opened in 1860, and both Legazpi and Tacloban were opened in 1873.[40]

Enlightenment

Before the start of the Philippine Revolution, Filipino society was subdivided into social classifications that were based on the economic status of a person. Background, ancestry, and economic status played a huge role in determining standing in the social hierarchy.

The Spanish people as well as Native descendants of precolonial nobility belonged to the upper class, and they were further subdivided into more classes: the peninsulares,creoles, and the Principalía. The peninsulares were people who were Spanish-born, but lived in the Philippines. The creoles, or criollo people, were Spaniards who were born in the colonies. The principalia was a hereditary class of local Indios who descended from precolonial datus, rajah and nobility, and were granted special rights and privileges such as positions in local government and the right to vote, though they were lower than the peninsulares and insulares in social standing. Many members of the Philippine Revolution belonged to the principalia class like Jose Rizal. Although the peninsulares and the creoles enjoyed the same social power, as they both belonged to the upper class, the peninsulares considered themselves as socially superior to the creoles and the native principalia.[41]

The lowest of the two classes was the masses, or Indios. This class included all poor commoners, peasants and laborers. Unlike the principalia class, where the members enjoyed high public offices and recommendations from the King of Spain, the masses only enjoyed a few civil rights and privileges. The highest political office that they could possibly hold was the gobernadorcillo, or the town executive. The members of Katipunan, the secret organization that would trigger the revolution, mainly consisted of the masses.[41]

Material prosperity at the start of 19th century produced an enlightened middle class in the Philippines, consisting of well-to-do farmers, teachers, lawyers, physicians, writers, and government employees. Many of them were able to buy and read books originally withheld from the lowly Filipino class. They discussed political problems and sought government reforms, and eventually, they were able to send their children to colleges and universities in Manila and abroad, particularly to Madrid. The material progress was primarily due to the opening of the Manila ports to world trade.[42]

The leading intellectuals of the country came from the enlightened middle class. They later called themselves the Ilustrados, which means "erudite ones". They also considered themselves to be the intelligentsia branch of the Filipino society. From the Ilustrados rose the prominent members of the Propaganda Movement, who stirred the very first flames of the revolution.[43]

Liberalism (1868–1874)

In 1868, a revolution overthrew the autocratic monarchy of Queen Isabella II of Spain, which was replaced by a civil and liberal government with Republican principles led by Francisco Serrano.[44]:107

The next year, Serrano appointed Carlos María de la Torre, a member of the Spanish army, as the 91st Governor-General of the Philippines. Filipino and Spanish liberals residing in the country welcomed him with a banquet at the Malacañan Palace on June 23, 1869. On the night of July 12, 1869, Filipino leaders, priests and students gathered and serenaded de la Torre at Malacañan Palace to express their appreciation for his liberal policies. The serenade was led by prominent residents of Manila, including José Cabezas de Herrera (the Civil Governor of Manila), José Burgos, Maximo Paterno, Manuel Genato, Joaquín Pardo de Tavera, Ángl Garchitorena, Andrés Nieto and Jacóbo Zóbel y Zangroniz.

An Assembly of Reformists, the Junta General de Reformas, was established in Manila. It consisted of five Filipinos, eleven Spanish civilians and five Spanish friars.[44]:362–363 They had the ability to vote on reforms, subject to ratification by the Home Government.[44]:363 However, none of the reforms were put into effect, due to the friars fearing that the reforms would diminish their influence. The Assembly ceased to exist after the 1874 Restoration.[44]:363

Rise of Filipino nationalism

In 1776, the first major challenge to monarchy in centuries occurred in the American Colonies. Although the American Revolution succeeded, it was in a relatively isolated area. In 1789, however, the French Revolution began to change the political landscape of Europe, as it ended absolute monarchy in France. The power passed from the king to the people through representation in parliament. People in other European countries began asking for representation, as well. In the Philippines, this idea spread through the writings of criollo writers, such as Luis Rodríguez Varela, who called himself "Conde Filipino" (Earl of the Philippines).[45] This was the first time that a colonist called himself a Filipino rather than a Spanish subject. With the increasing economic and political stability in the Philippines, the middle class began demanding that the churches in the Philippines be nationalized through a process known as Secularization. In this process, control of Philippine parishes were to be passed from the religious orders to the secular priests, particularly Philippine-born priests. The religious orders, or friars, reacted negatively and a political struggle between the friars and secular priests began.

The 19th century was also a new era for Europe. Church power was declining, and friars began coming to the Philippines, ending hopes that the friars would relinquish their posts. With the opening of the Suez Canal, the voyage between Spain and the Philippines was made shorter. More peninsulares (Spaniards born in Spain) began pouring into the colony and started to occupy the various government positions traditionally held by the criollos (Spaniards born in the Philippines). In the 300 years of colonial rule, the criollos had been accustomed to being semi-autonomous with the governor-general, who was the only Spaniard (peninsulares) government official. The criollos demanded representation in the Spanish Cortes where they could express their grievances. This, together with the secularization issues, gave rise to the Criollo Insurgencies.

Criollo insurgencies

In the late 18th century, Criollo (or Insulares, "islanders", as they were locally called) writers began spreading the ideals of the French Revolution in the Philippines. At the same time, a royal decree ordered the secularization of Philippine churches, and many parishes were turned over to Philippine-born priests. Halfway through the process, it was aborted due to the return of the Jesuits. The religious orders began retaking Philippine parishes. One instance that enraged the Insulares was the Franciscan takeover of Antipolo, the richest parish in the islands, which had been under the control of Philippine-born priests. In the early 19th century, Fathers Pedro Peláez and Mariano Gómez began organizing activities which demanded that control of Philippine parishes be returned to the Filipino seculars. Father Peláez, who was Archbishop of the Manila Cathedral, died in an earthquake, while Father Gómez retired to private life. The next generation of Insular activists included Father José Burgos, who organized the student rallies in the University of Santo Tomas. On the political front, Insular activists included Joaquín Pardo de Tavera and Jacobo Zobel. The unrest escalated into a large insurgency in 1823 when Andres Novales, a creole captain, declared the Philippines to be independent from Spain and crowned himself Emperor of the Philippines.[45] In January 1872, the Insular uprisings began when soldiers and workers of the Cavite Arsenal of Fort San Felipe mutinied. They were led by Sergeant Ferdinand La Madrid, a Spanish mestizo. The soldiers mistook the fireworks in Quiapo, which were being fired for the feast of St. Sebastian, as the signal to start a long-planned national uprising. The colonial government used the incident to spread a reign of terror and to eliminate subversive political and church figures. Among these were Priest Mariano Gómez, José Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora, who were executed by garrote on February 18, 1872. They are remembered in Philippine history as Gomburza.[45]

Organizations

La Solidaridad, La Liga Filipina and the Propaganda Movement

The Cavite Mutiny of 1872, and the subsequent deportation of criollos and mestizos to the Mariana Islands and Europe, created a colony of Filipino expatriates in Europe, particularly in Madrid. In Madrid, Marcelo H. del Pilar, Mariano Ponce, Eduardo Leyte, and Antonio Luna founded La Solidaridad, a newspaper that pressed for reforms in the Philippines and spread ideas of revolution.[44]:363 This effort is known as the Propaganda Movement, and the result was the founding of secret societies in villages.[44]:363 Among the pioneering editors of the paper were Graciano López Jaena, Marcelo H. del Pilar, and José Rizal. The editors of La Solidaridad also included leading Spanish liberals, such as Morayta.[46] The Propaganda Movement in Europe resulted in the Spanish legislature passing some reforms for the islands, but the colonial government did not implement them. After being published from 1889 to 1895, La Solidaridad began to run out of funds, and it had not accomplished concrete changes in the Philippines. José Rizal decided to return to the Philippines, where he founded La Liga Filipina, the Manila chapter of the Propaganda Movement.

Only days after its founding, Rizal was arrested by colonial authorities and deported to Dapitan, and the Liga was soon disbanded.[46] Ideological differences had contributed to its dissolution. Conservative upper-class members favoring reform, under the leadership of Apolinario Mabini, set up the Cuerpo de Compromisarios, which attempted to revive La Solidaridad in Europe. Other, more radical members belonging to the middle and lower classes, led by Andrés Bonifacio, set up the Katipunan alongside the revived Liga.

The goals of the Propaganda Movement included legal equality of Filipinos and Spaniards, restoration of Philippine representation in the Spanish Cortes, "Filipinization" of the Catholic parishes, and the granting of individual liberties to Filipinos, such as freedom of speech, freedom of press, freedom of assembly, and freedom to petition for grievances.[47]

Katipunan

| Participant at the Philippine Revolution | |

Flag of the Katipunan, 1892 | |

| Background | |

|---|---|

| Events | Various revolts and uprisings |

| Factions | |

| Key organizations | Propaganda Movement La Liga Filipina |

| Objects | Noli Me Tángere El filibusterismo La Solidaridad |

| Organization | |

| Leaders | Andrés Bonifacio Emilio Aguinaldo Ladislao Diwa Gregoria de Jesús Teodoro Plata Román Basa Deodato Arellano Valentín Díaz José Dizon Pio del Pilar |

| Members | Melchora Aquino others |

Andrés Bonifacio, Deodato Arellano, Ladislao Diwa, Teodoro Plata and Valentín Díaz founded the Katipunan (in full, Kataas-taasang, Kagalang-galangang Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan[48] "Supreme and Venerable Society of the Children of the Nation") in Manila on July 7, 1892. The organization, advocating independence through armed revolt against Spain, was influenced by the rituals and organization of Freemasonry; Bonifacio and other leading members were also Freemasons.

From Manila, the Katipunan expanded into several provinces, including Batangas, Laguna, Cavite, Bulacan, Pampanga, Tarlac, Nueva Ecija, Ilocos Sur, Ilocos Norte, Pangasinan, Bicol and Mindanao. Most of the members, called Katipuneros, came from the lower and middle classes. The Katipunan had "its own laws, bureaucratic structure and elective leadership".[3] The Katipunan Supreme Council (Kataas-taasang Kapulungan, of which Bonifacio was a member, and eventually head) coordinated provincial councils (Sangguniang Bayan).[4] The provincial councils were in charge of "public administration and military affairs on the supra-municipal or quasi-provincial level".[3] Local councils (Panguluhang Bayan)[4] were in charge of affairs "on the district or barrio level."[3] By 1895, Bonifacio was the supreme leader (Supremo) or supreme president (Presidente Supremo)[49][50] of the Katipunan and was the head of its Supreme Council. Some historians estimate that there were between 30,000 and 400,000 members by 1896; other historians argue that there were only a few hundred to a few thousand members.[51]

Course of the Revolution

The existence of the Katipunan eventually became known to the colonial authorities through Teodoro Patiño, who revealed it to the Spaniard La Font, general manager of the printing shop Diario de Manila.[49]:29–31 Patiño was engaged in a bitter dispute over pay with a co-worker, Katipunero member Apolonio de la Cruz, and exposed the Katipunan in revenge.[52]:30–31 La Font led a Spanish police lieutenant to the shop and to the desk of Apolonio, where they "found Katipunan paraphernalia such as a rubber stamp, a little book, ledgers, membership oaths signed in blood, and a membership roster of the Maghiganti chapter of the Katipunan."[52]:31

As with the Terror of 1872, colonial authorities made several arrests and used torture to identify other Katipunan members.[52]:31 Despite having no involvement in the secessionist movement, many of them were executed, notably Don Francisco Roxas. Bonifacio had forged their signatures in Katipunan documents, hoping that they would be forced to support the revolution.

On 24 August 1896, Bonifacio called Katipunan members to a mass gathering in Caloocan, where the group decided to start a nationwide armed revolution against Spain.[3][52]:34–35 The event included a mass tearing of cedulas (community tax certificates) accompanied by patriotic cries. The exact date and location are disputed, but two possibilities have been officially endorsed by the Philippine government: August 26 in Balintawak and later, August 23 in Pugad Lawin. Thus, the event is called the "Cry of Pugad Lawin" or "Cry of Balintawak". However, the issue is further complicated by other possible dates such as August 24 and 25 and other locations such as Kangkong, Bahay Toro and Pasong Tamo. Furthermore, at the time, "Balintawak" referred not only to a specific place, but also a general area that included some of the proposed sites, such as Kangkong.[53][54]

Upon the discovery of the Katipunan, Bonifacio called all Katipunan councils to a meeting in Balintawak[55] or Kangkong[52][56] to discuss their situation. According to historian Teodoro Agoncillo, the meeting occurred on August 19;[55] however, revolutionary leader Santiago Álvarez stated that it occurred on August 22.[52][56]

On August 21, Katipuneros were already congregating in Balintawak[55] in Caloocan.[52][56] Late in the evening, amidst heavy rain, the rebels moved to Kangkong in Caloocan, and arrived there past midnight.[52][56] As a precaution, the rebels moved to Bahay Toro[52] or Pugad Lawin[53] on August 23. Agoncillo places the Cry and tearing of certificates at the house of Juan Ramos, which was in Pugad Lawin.[53] Alvarez writes that they met at the house of Melchora Aquino (known as "Tandang Sora", and mother of Juan Ramos) in Bahay Toro on that date.[52][56] Agoncillo places Aquino's house in Pasong Tamo and the meeting there on August 24.[57] The rebels continued to congregate, and by August 24, there were over a thousand.[52][56]

On August 24, it was decided to notify the Katipunan councils of the surrounding towns that an attack on the capital Manila was planned for August 29.[52][56][57] Bonifacio appointed generals to lead rebel forces in Manila. Before hostilities erupted, Bonifacio also reorganized the Katipunan into an open revolutionary government, with himself as president and the Supreme Council of the Katipunan as his cabinet.[4][52]

On the morning of August 25, the rebels came under attack by a Spanish civil guard unit, with the rebels having greater numbers but the Spanish being better armed. The forces disengaged after a brief skirmish and some casualties on both sides.[52][56][57]

Another skirmish took place on August 26, which sent the rebels retreating toward Balara. At noon, Bonifacio and some of his men briefly rested in Diliman. In the afternoon, civil guards sent to Caloocan to investigate attacks on Chinese merchants — done by bandits who had attached themselves to the rebels—came across a group of Katipuneros and briefly engaged them.[44]:367 The commander of the guards, Lieutenant Ros, reported the encounter to the authorities, and the report drove Governor-General Ramón Blanco to prepare for coming hostilities.[52][56] General Blanco had about 10,000 Spanish regulars and the gunboats Isla de Cuba and Isla de Luzon by the end of November.[44]:365

From August 27 to 28, Bonifacio moved from Balara to Mt. Balabak in Hagdang Bato, Mandaluyong. There, he held meetings to finalize plans for the Manila attack the following day. Bonifacio issued the following general proclamation:

This manifesto is for all of you. It is absolutely necessary for us to stop at the earliest possible time the nameless oppositions being perpetrated on the sons of the country who are now suffering the brutal punishment and tortures in jails, and because of this please let all the brethren know that on Saturday, the 29th of the current month, the revolution shall commence according to our agreement. For this purpose, it is necessary for all towns to rise simultaneously and attack Manila at the same time. Anybody who obstructs this sacred ideal of the people will be considered a traitor and an enemy, except if he is ill; or is not physically fit, in which case he shall be tried according to the regulations we have put in force. Mount of Liberty, 28 August 1896 – ANDRÉS BONIFACIO[56]

The conventional view among Filipino historians is that Bonifacio did not carry out the planned Katipunan attack on Manila the following day and instead attacked a powder magazine at San Juan del Monte.[58][59] However, more recent studies have advanced the view that the planned attack did occur; according to this view, Bonifacio's battle at San Juan del Monte (now called the "Battle of Pinaglabanan") was only a part of a bigger "battle for Manila" hitherto unrecognized as such.[4][56]

Hostilities in the area started on the evening of August 29, when hundreds of rebels attacked the Civil Guard garrison in Pasig, just as hundreds of other rebels personally led by Bonifacio were amassing in San Juan del Monte, which they attacked at about 4 a.m. on the 30th.[44]:368 Bonifacio planned to capture the San Juan del Monte powder magazine[44]:368 along with a water station which supplied Manila. The Spaniards, outnumbered, fought a delaying battle until reinforcements arrived. Once reinforced, the Spaniards drove Bonifacio's forces back with heavy casualties. Elsewhere, rebels attacked Mandaluyong, Sampaloc, Sta. Ana, Pandacan, Pateros, Marikina, and Caloocan,[56] as well as Makati and Taguig.[58] Balintawak in Caloocan saw intense fighting. Rebel troops tended to gravitate towards fighting in San Juan del Monte and Sampaloc.[56] South of Manila, a thousand-strong rebel force attacked a small force of civil guards. In Pandacan, Katipuneros attacked the parish church, making the parish priest run for his life.[58]

After their defeat in Battle of San Juan del Monte, Bonifacio's troops regrouped near Marikina, San Mateo and Montalban, where they proceeded to attack these areas. They captured the areas, but were driven back by Spanish counterattacks, and Bonifacio eventually ordered a retreat to Balara. On the way, Bonifacio was nearly killed shielding Emilio Jacinto from a Spanish bullet that grazed his collar.[58] Despite his retreat, Bonifacio was not completely defeated and was still considered to be a threat.[4][56]

South of Manila, the towns of San Francisco de Malabon, Noveleta and Kawit in Cavite rebelled a few days after.[58] In Nueva Ecija, north of Manila, rebels in San Isidro, led by Mariano Llanera, attacked the Spanish garrison on September 2–4; they were repulsed.[60]

By August 30, the revolt had spread to eight provinces. On that date, Governor-General Blanco declared a "state of war" in these provinces and placed them under martial law.[44]:368 These provinces were Manila, Bulacan, Cavite, Pampanga, Tarlac, Laguna, Batangas, and Nueva Ecija.[45][58][61] They would later be represented as the eight rays of the sun in the Filipino flag.

The rebels had few firearms; they were mostly armed with bolo knives and bamboo spears. The lack of guns has been proposed as a possible reason why the Manila attack allegedly never succeeded.[58] Also, the Katipunan leaders from Cavite had earlier expressed reservations about starting an uprising due to their lack of firearms and preparation. As a result, they did not send troops to Manila, but instead attacked garrisons in their own locales. Some historians have argued that the Katipunan defeat in the Manila area was (partly) the fault of the Cavite rebels due to their absence, as their presence would have proved crucial.[4][56] In their memoirs, Cavite rebel leaders justified their absence in Manila by claiming Bonifacio failed to execute pre-arranged signals to begin the uprising, such as setting balloons loose and extinguishing the lights at the Luneta park. However, these claims have been dismissed as "historical mythology"; as reasoned by historians, if they were really waiting for signals before marching on Manila, they would have arrived "too late for the fray". Bonifacio's command for a simultaneous attack is interpreted as evidence that such signals were never arranged.[4][56] Other factors for the Katipunan defeat include the capture of Bonifacio's battle plans by Spanish intelligence. The Spanish concentrated their forces in the Manila area while pulling out troops in other provinces (which proved beneficial for rebels in other areas, particularly Cavite). The authorities also transferred a regiment of 500 native troops to Marawi, Mindanao, where the soldiers later rebelled.[4][56]

Final Statement and Execution of José Rizal

When the revolution broke out, Rizal was in Cavite, awaiting the monthly mailboat to Spain. He had volunteered, and been accepted, for medical service in the Cuban War of Independence. The mailboat left on September 3 and arrived in Barcelona, which was under martial law, on October 3, 1896. After a brief confinement at Montjuich prison, Rizal was told by Captain-General Eulogio Despujol that he would not be going on to Cuba, but would be sent back to the Philippines instead. Upon his return, he was imprisoned in Fort Santiago.

While incarcerated, Rizal petitioned Governor-General Ramón Blanco for permission to make a statement on the rebellion.[62] His petition was granted, and Rizal wrote the Manifesto á Algunos Filipinos, wherein he decried the use of his name "as a war-cry among certain people who were up in arms",[63] stated that "for reforms to bear fruit, they must come from above, since those that come from below will be irregular and uncertain shocks",[64] and affirmed that he "condemn[s], this absurd, savage insurrection".[64] However, the text was suppressed on the recommendation of the Judge-Advocate General.[64]

Revolution in Cavite

By December, there were three major centers of rebellion: Cavite (under Mariano Alvarez, Baldomero Aguinaldo and others), Bulacan (under Mariano Llanera) and Morong (now part of Rizal, under Bonifacio). Bonifacio served as tactician for the rebel guerillas, though his prestige suffered when he lost battles that he personally led.[4]

Meanwhile, in Cavite, Katipuneros under Mariano Álvarez, Bonifacio's uncle by marriage, and Baldomero Aguinaldo of Cavite El Viejo (modern Kawit), won early victories. The Magdalo council commissioned Edilberto Evangelista, an engineer, to plan the defense and logistics of the revolution in Cavite. His first victory was in the Battle of Imus on September 1, 1896, defeating the Spanish forces under General Ernesto Aguirre with the aid of Jose Tagle. The Cavite revolutionaries, particularly Emilio Aguinaldo, won prestige through defeating Spanish troops in "set piece" battles, while other rebels like Bonifacio and Llanera were engaged in guerrilla warfare. Aguinaldo, speaking for the Magdalo ruling council, issued a manifesto proclaiming a provisional and revolutionary government after his early successes, despite the existence of Bonifacio's Katipunan government.[65]

The Katipunan in Cavite was divided into two councils: the Magdiwang (led by Alvarez) and the Magdalo (led by Baldomero Aguinaldo, Emilio's cousin). At first, these two Katipunan councils cooperated with each other in the battlefield, as in the battles of Binakayan and Dalahican, where they won their first major victory over the Spaniards. However, rivalries between command and territory soon developed, and they refused to cooperate with each other in battle.

To unite the Katipunan in Cavite, the Magdiwang, through Artemio Ricarte and Pio Del Pilar, called Bonifacio, who was fighting in Morong (present-day Rizal) province to mediate between the factions. Perhaps due to his kinship ties with their leader, Bonifacio was seen as partial to the Magdiwang.[66]

It was not long before the issue of leadership was debated. The Magdiwang faction recognized Bonifacio as supreme leader, being the head of the Katipunan. The Magdalo faction agitated for Emilio Aguinaldo to be the movement's head because of his successes in the battlefield compared to Bonifacio's record of personal defeats. Meanwhile, the Spanish troops, now under the command of the new Governor-General Camilo de Polavieja, steadily gained ground.

Tejeros Convention

On December 31, an assembly was convened in Imus to settle the leadership dispute. The Magdalo insisted on the establishment of revolutionary government to replace the Katipunan. The Magdiwang favored retention of the Katipunan, arguing that it was already a government in itself. The assembly dispersed without a consensus.[67]

On March 22, 1897, another meeting was held in Tejeros. It called for the election of officers for the revolutionary government, which was in need of united military forces, as there was a pending Spanish offensive against the Magdalo faction. The Magdiwang faction allied with Bonifacio and prepared and hosted the election, as most of the Magdalo faction was occupied by battle preparations. Bonifacio chaired the election and stated that the election results were to be respected. When the voting ended, Bonifacio had lost and the leadership turned over to Aguinaldo, who was away fighting in Pasong Santol. Bonifacio also lost other positions to members of his Magdiwang faction. Instead, he was elected as Director of the Interior, but his qualifications were questioned by a Magdalo, Daniel Tirona. Bonifacio felt insulted and would have shot Tirona if Artemio Ricarte had not intervened. Invoking his position of Supremo of the Katipunan, Bonifacio declared the election void and stomped out in anger.[68] Aguinaldo took his oath of office as president the next day in Santa Cruz de Malabon (present-day Tanza) in Cavite, as did the rest of the officers, except for Bonifacio.[69]

Execution of Bonifacio

Bonifacio moved his headquarters to Naic after the fall of Imus.[49]:112 In Naic, Bonifacio and his officers created the Naic Military Agreement, establishing a rival government to the newly constituted government of Aguinaldo. It rejected the election at Tejeros and asserted that Bonifacio was the leader of the revolution. It also ordered that Filipino men be forced to enlist in Bonifacio's army. The agreement eventually called for a coup d'état against the established government. When Limbon in Indang, a town in Cavite, refused to supply provisions, Bonifacio ordered it to be burned.[49]:117 When Aguinaldo learned about the Naic Military Agreement and the reports of abuse, he ordered the arrest of Bonifacio and his soldiers (without Bonifacio's knowledge) on April 27, 1897.[49]:120 Colonel Agapito Bonzon met with Bonifacio in Limbon and attacked him the next day. Bonifacio and his brother Procopio were wounded, while their brother Ciriaco was killed on April 28.[49]:121 They were taken to Naic to stand trial.[49]:124

The Consejo de Guerra (War Council) sentenced Andrés and Procopio to death on May 10, 1897, for committing sedition and treason.[54] Aguinaldo supported deportation of Andrés and Procopio rather than execution,[49]:140 but withdrew his decision as a result of pressure from Pio Del Pilar and other officers of the revolution.

On May 10, Major Lazaro Makapagal, upon orders from General Mariano Noriel, executed the Bonifacio brothers[49]:143 at the foothills of Mount Buntis,[54] near Maragondon. Andrés and Procopio were buried in a shallow grave, marked only with twigs.

Biak-na-Bato

Augmented by new recruits from Spain, government troops recaptured several towns in Cavite, taking Imus on 25 March 1897.[49]:110 The head of the Spanish expeditionary force, General de Lacambre, then offered amnesty to all who would surrender and accept Spanish authority.[49]:111 In May 1897, the Spanish captured Maragondon, forcing the Government of the Philippine Republic to move to Mt. Buntis.[49]:146 By June, the Spanish had taken Mendez Nunez, Amadeo, Alfonso, Bailen and Magallanes with little resistance.[49]:149 The Spanish planned war, including the concentration of rebel relatives and friends in camps.[49]:222

As argued by Apolinario Mabini and others, the succession of defeats for the rebels could be attributed to discontent that resulted from Bonifacio's death. Mabini wrote:

This tragedy smothered the enthusiasm for the revolutionary cause, and hastened the failure of the insurrection in Cavite, because many from Manila, Laguna and Batangas, who were fighting for the province (of Cavite), were demoralized and quit...[70]

In other areas, some of Bonifacio's associates, such as Emilio Jacinto and Macario Sakay, never subjected their military commands to Aguinaldo's authority.

Aguinaldo and his men retreated northward, from one town to the next, until they finally settled in Biak-na-Bato, in the town of San Miguel de Mayumo in Bulacan. Here they established what became known as the Republic of Biak-na-Bato, with a constitution drafted by Isabelo Artacho and Felix Ferrer; it was based on the first Cuban Constitution.[71]

With the new Spanish Governor-General Fernando Primo de Rivera declaring, "I can take Biak-na-Bato. Any army can capture it. But I cannot end the rebellion[72] ", he proffered peace to the revolutionaries. A lawyer named Pedro Paterno volunteered to be negotiator between the two sides. For four months, he traveled between Manila and Biak-na-Bato. His hard work finally bore fruit when, on December 14 to December 15, 1897, the Pact of Biak-na-Bato was signed. Consisting of three documents, it called for the following agenda:[73]

- The surrender of all weapons of the revolutionaries.

- Amnesty for those who participated in the revolution..

- Exile for the revolutionary leadership.

- Payment by the Spanish government of $400,000 (Mexican peso) to the revolutionaries in three installments: $200,000 (Mexican peso) upon leaving the country, $100,000 (Mexican peso) upon the surrender of at least 700 firearms, and another $200,000 (Mexican peso) upon the declaration of general amnesty.[74]

Leaving Biak-na-Bato on December 24, 1897, Aguinaldo and eighteen other top officials of the revolution, including Mariano Llanera, Tomás Mascardo, Benito Natividad, Gregorio del Pilar, and Vicente Lukban were banished to Hong Kong with $400,000 (Mexican peso) by December 29.[49]:229 The rest of the men got $200,000 (Mexican peso) and the third installment was never received. General amnesty was never declared because sporadic skirmishes continued.

Second Phase of the revolution

Not all the revolutionary generals complied with the treaty. One, General Francisco Macabulos, established a Central Executive Committee to serve as the interim government until a more suitable one was created. Armed conflicts resumed, this time coming from almost every province in the Philippines. The colonial authorities, on the other hand, continued the arrest and torture of those suspected of committing banditry.

The Pact of Biak-na-Bato did not signal an end to the revolution. Aguinaldo and his men were convinced that the Spaniards would never give the rest of the money promised to them as a condition of surrender. Furthermore, they believed that Spain reneged on her promise of amnesty. The Filipino patriots renewed their commitment for complete independence. They purchased more arms and ammunition to ready themselves for another siege.

The Battle of Kakarong de Sili

During the Philippine Revolution, Pandi, Bulacan, played a vital and historical role in the fight for Philippine independence. Pandi is historically known for the Real de Kakarong de Sili Shrine – Inang Filipina Shrine, the site where the bloodiest revolution in Bulacan took place, where more than 3,000 Katipunero revolutionaries died. Likewise, it is on this site where the 'Republic of Real de Kakarong de Sili' of 1896, one of the first Philippine revolutionary republics, was established. It was also in Kakarong de Sili that the Kakarong Republic[75] was organized shortly after the Cry of Pugad Lawin (referred to as "The Cry of Balintawak") by about 6,000 Katipuneros from various towns of Bulacan, headed by Brigadier General Eusebio Roque (better known as "Maestrong Sebio or Dimabungo").[76]

Kakarong Republic

History and researchers, as well as records of the National Historical Commission, tells that the Kakarong Republic was the first truly organized revolutionary government established in the country to overthrow the Spaniards, antedating even the famous Malolos Republic and the Biak-na-Bato Republic. In recognition thereof, these three "Republics" established in Bulacan have been incorporated in the provincial seal. The Kakarong Republic, established in late 1896, grew out of the local Katipunan chapter in the town of Pandi, Bulacan, called the Balangay Dimas-Alang.

According to available records, including the biography of General Gregorio del Pilar, entitled "Life and Death of a Boy General" (written by Teodoro Kalaw, former director of the National Library of the Philippines), a fort was constructed at Kakarong de Sili that was like a miniature city. It had streets, an independent police force, a military band, a military arsenal with factories for bolos and artillery, and repair shops for rifles and cartridges. The Kakarong Republic had a complete set of officials, with Canuto Villanueva as Supreme Chief and Captain General of the military forces, and Eusebio Roque, also known by his nom-de-guerre "Maestrong Sebio", then head of the Katipunan local organization, as Brigadier General of the Army of the Republic. The fort was attacked and completely destroyed on January 1, 1897, by a large Spanish force headed by General Olaguer-Feliu.[77] General Gregorio del Pilar was only a lieutenant at that time, and the Battle of Kakarong de Sili was his first "baptism of fire". This was where he was first wounded and escaped to Manatal, a nearby barangay.

In memory of the 1,200 Katipuneros who perished in the battle, the Kakarong Lodge No. 168 of the Legionarios del Trabajo erected a monument of the Inang Filipina Shrine (Mother Philippines Shrine) in 1924 in the barrio of Kakarong in Pandi, Bulacan. The actual site of the Battle of Kakarong de Sili is now a part of the barangay of Real de Kakarong. Emilio Aguinaldo visited this ground in his late fifties.

Spanish–American War

In February 1898, during an ongoing revolution in Cuba, the explosion and sinking of a U.S. Navy warship in Havana harbor led the United States to issue a declaration of war against Spain in April of that year. On April 25, Commodore George Dewey sailed for Manila with a fleet of seven U.S. ships. Upon arriving on May 1, Dewey encountered a fleet of twelve Spanish ships commanded by Admiral Patricio Montojo. The subsequent Battle of Manila Bay only lasted for a few hours, with all of Montojo's fleet destroyed. Dewey called for armed reinforcements and, while waiting, acted as a blockade for Manila Bay.[78][79]

Aguinaldo returns to the Philippines

On May 7, 1898, USS McCulloch, an American dispatch boat, arrived in Hong Kong from Manila, bringing reports of Dewey's victory in the Battle of Manila Bay, but with no orders regarding the transportation of Aguinaldo. McCulloch again arrived in Hong Kong on May 15, bearing orders to transport Aguinaldo to Manila. Aguinaldo departed Hong Kong aboard McCulloch on May 17, arriving in Manila Bay on May 19.[80] Several revolutionaries, as well as Filipino soldiers employed by the Spanish army, crossed over to Aguinaldo's command.

In the Battle of Alapan on May 28, 1898, Aguinaldo raided the last remaining stronghold of the Spanish Empire in Cavite with fresh reinforcements of about 12,000 men. This battle eventually liberated Cavite from Spanish colonial control and led to the first time the modern flag of the Philippines being unfurled in victory.

Soon after, Imus and Bacoor in Cavite, Parañaque and Las Piñas in Morong, Macabebe, and San Fernando in Pampanga, as well as Laguna, Batangas, Bulacan, Nueva Ecija, Bataan, Tayabas (present-day Quezon), and the Camarines provinces, were liberated by the Filipinos. They were also able to capture the port of Dalahican in Cavite.

Declaration of Independence

By June 1898, the island of Luzon, except for Manila and the port of Cavite, was under Filipino control, after General Monet's retreat to Manila with his remaining force of 600 men and 80 wounded.[44]:445 The revolutionaries were laying siege to Manila and cutting off its food and water supply. With most of the archipelago under his control, Aguinaldo decided it was time to establish a Philippine government. When Aguinaldo arrived from Hong Kong, he had brought with him a copy of a plan drawn by Mariano Ponce, calling for the establishment of a revolutionary government. Upon the advice of Ambrosio Rianzares Bautista, however, an autocratic regime was established on May 24, with Aguinaldo as dictator. It was under this dictatorship that independence was finally proclaimed on June 12, 1898, in Aguinaldo's house in Kawit, Cavite. The first Filipino flag was again unfurled and the national anthem was played for the first time. Apolinario Mabini, Aguinaldo's closest adviser, opposed Aguinaldo's decision to establish an autocracy. He instead urged Aguinaldo to create a revolutionary government. Aguinaldo refused to do so; however, Mabini was eventually able to convince him. Aguinaldo established a revolutionary government on July 23, 1898.

Capture of Manila

The United States Navy continued to wait for reinforcements. Refusing to allow the Filipinos to participate, reinforced U.S. forces captured Manila on August 13, 1898.

First Philippine Republic

.svg.png)

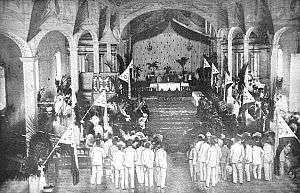

Upon the recommendations of the decree that established the revolutionary government, a Congreso Revolucionario was assembled at Barasoain Church in Malolos, Bulacan on September 15.[44]:469 All of the delegates to the congress were from the ilustrado class. Mabini objected to the call for a constitutional assembly; when he did not succeed, he drafted a constitution of his own, which also failed. A draft by an ilustrado lawyer, Felipe Calderón y Roca, was instead presented, and this became the framework upon which the assembly drafted the first constitution, the Malolos Constitution. On November 29, the assembly, now popularly called the Malolos Congress, finished the draft. However, Aguinaldo, who always placed Mabini in high esteem and heeded most of his advice, refused to sign the draft when the latter objected. On January 21, 1899, after some modifications were made to suit Mabini's arguments, the constitution was finally approved by the Congress and signed by Aguinaldo. Two days later, the Philippine Republic (also called the First Republic and Malolos Republic) was established in Malolos with Aguinaldo as president.[44]:486

Philippine–American War

On February 4, 1899, hostilities between Filipino and American forces began when an American sentry patrolling between Filipino and American lines shot a Filipino soldier. The Filipino forces returned fire, thus igniting a second battle for Manila. Aguinaldo sent a ranking member of his staff to Ellwell Otis, the U.S. military commander, with the message that the firing had been against his orders. According to Aguinaldo, Otis replied, "The fighting, having begun, must go on to the grim end."[81] The Philippines declared war against the United States on June 2, 1899, with Pedro Paterno, President of the Congress of the First Philippine Republic, issuing a Proclamation of War.[10]

As the First Philippine Republic was never recognized as a sovereign state, and the United States never formally declared war, the conflict was not concluded by a treaty. On July 2, 1902, the United States Secretary of War telegraphed that since the insurrection against the United States had ended and provincial civil governments had been established throughout most of the Philippine archipelago, the office of military governor was terminated.[82] On July 4, Theodore Roosevelt, who had succeeded to the U.S. presidency after the assassination of William McKinley, proclaimed an amnesty to those who had participated in the conflict.[82][83] On April 9, 2002, Philippine President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo proclaimed that the Philippine–American War had ended on April 16, 1902 with the surrender of General Miguel Malvar,[84] and declared the centennial anniversary of that date as a national working holiday and as a special non-working holiday in the Province of Batangas and in the Cities of Batangas, Lipa and Tanauan.[85]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Philippine Revolution. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Philippine Revolution. |

Notes

- If one includes the Spanish-American and Philippine-American wars in the period called the "Philippine Revolution", then 1902 would be the end date of that period. To avoid duplication between the Philippine Revolution and the Philippine–American War articles, this article treats the Philippine Revolution as having ended with the naval Mock Battle of Manila in 1898.

- Alexander M. Bielakowski (2013). Ethnic and Racial Minorities in the U.S. Military: A-L. ABC-CLIO. p. 204. ISBN 978-1-59884-427-6.

- Guererro, Milagros; Encarnacion, Emmanuel; Villegas, Ramon (1996), "Andres Bonifacio and the 1896 Revolution", Sulyap Kultura, National Commission for Culture and the Arts, 1 (2): 3–12, archived from the original on 2010-11-15, retrieved 2009-07-08

- Custodio & Dalisay 1998.

- Newton-Matza, Mitchell (March 2014). Disasters and Tragic Events: An Encyclopedia of Catastrophes in American History. ABC-CLIO. p. 165.

- Marshall Cavendish Corporation (2007). World and Its Peoples: Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, and Brunei. Marshall Cavendish. p. 1181.

- Wesling, Meg (2011). Empire's Proxy: American Literature and U.S. Imperialism in the Philippines. NYU Press. p. 39.

- Halstead 1898, p. 318

- Kalaw 1927, pp. 199–200

- Pedro Paterno's Proclamation of War, MSC Schools, Philippines, June 2, 1899, retrieved 17 October 2007

- Bautista, Ma. Lourdes S; Bolton, Kingsley (November 2008). Philippine English: Linguistic and Literary. Hong Kong University Press. p. 2.

- "Spanish Colony 1565–1898". University of Alberta. Retrieved 20 October 2009.

- Tucker, Phillip Thomas (March 2002). Cubans in the Confederacy: Jose Agustin Quintero, Ambrosio Jose Gonzales, and Loreta Janeta Velazquez. McFarland. p. 95.

- O'Gorman Anderson, Benedict Richard (2005). Under Three Flags: Anarchism and the Anti-colonial Imagination. Verso. p. 57.

- Institut Kajian Dasar Malaysia (1996). José Rizal and the Asian renaissance. Institut Kajian Dasar. p. 193.

- "Nationalista Party History". Archived from the original on 27 June 2007. Retrieved 30 July 2007.

- Lone 2007, p. 42

- Titherington 1900, pp. 357–358.

- Kalaw 1927, pp. 413–417 Appendix A

- Guevara 1972, p. 10

- Kalaw 1927, pp. 423–429 Appendix C

- Kalaw 1927, pp. 199–200 Ch.7

- Worcester 1914, p. 180

- "GENERAL AMNESTY FOR THE FILIPINOS; Proclamation Issued by the President" (PDF), The New York Times, 4 July 1902, retrieved 5 February 2008

- "Spanish Occupation". Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- "The Death of Gomburza & The Propaganda Movement". Philippine-History.org. Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- "Letters and Addresses of Jose Rizal", Philippine Education, Manila: 315, December 1915.

- Zaide 1957, p. 63

- Montero y Vidal 1887, p. 360

- Blair & Robertson 1903–1909, p. 10296

- Blair & Robertson 1903–1909, p. 51071

- Zaide 1957, p. 64

- de Moya 1883, p. 183

- Jagor 1873, p. 16

- Diaz Arenas 1838, p. 4

- Diaz Arenas 1838, p. 10

- Regidor & Mason 1905, pp. 19–29

- Blair & Robertson 1903–1909, p. 10315

- Blair & Robertson 1903–1909, p. 10453

- Bowring 1859, p. 247

- Zaide 1957, p. 81

- Zaide 1957, p. 82

- Zaide 1957, p. 107

- Foreman 1906

- Joaquin, Nick (1990). Manila,My Manila. Vera-Reyes, Inc.

- Keat2004, p. 755

- "10. José Rizal and the Propaganda Movement". Philippines: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress. 1991.

- The Project Gutenberg eBook: Kartilyang Makabayan.

- Alvarez 1992

- :244

- Schumacher 1991, p. 196

- Alvarez & Malay 1992

- Agoncillo 1990, pp. 171–172

- Gatbonton 2000.

- Agoncillo 1990, p. 171

- Salazar 1994

- Agoncillo 1990, p. 172

- Agoncillo 1990, p. 173

- Zaide 1954, p. 115.

- Agoncillo 1990, p. 174

- Lone 2007, p. 37

- Anderson 2005, p. 161.

- Anderson 2005, p. 162.

- Anderson 2005, p. 163.

- Constantino 1975, pp. 179–180.

- Rodao & Rodríguez 2001, pp. 40, 287

- Agoncillo 1990, pp. 176–177

- Agoncillo 1990, pp. 177–179

- Sagmit 2007, p. 158

- Mabini 1969

-

- "Secessionist insurgency in south Philippines – 1969/2008 updated at February 2008". bippi.org. February 2008. Archived from the original on 8 August 2009.

- Aguinaldo 1899

- The Mexican dollar at the time was worth about 50 U.S. cents, according to Halstead 1898, p. 126

- "History of Pandi & The Kakarong Republic". sagippandi.blogspot.com. May 19, 2016.

- Halili 2004, p. 145.

- Halili 2004, p. 145-146.

- Battle of Manila Bay, 1 May 1898, Department of the Navy — Naval Historical Center. Retrieved on 10 October 2007.

- The Battle of Manila Bay by Admiral George Dewey, The War Times Journal. Retrieved on 10 October 2007.

- Aguinaldo 1899 Chapter III.

- Blanchard 1996, p. 130

- Worcester 1914, p. 293.

- "General amnesty for the Filipinos; proclamation issued by the President" (PDF). The New York Times. New York City. July 4, 1902.

- "Speech of President Arroyo during the Commemoration of the Centennial Celebration of the end of the Philippine-American War April 16, 2002". Official Gazette. Government of the Philippines. Archived from the original on 2016-10-11.

- Macapagal Arroyo, Gloria (April 9, 2002). "Proclamation No. 173. s. 2002". Manila: Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Archived from the original on December 28, 2016. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

References

- Agoncillo, Teodoro C. (1990) [1960], History of the Filipino People (8th ed.), Quezon City: Garotech Publishing, ISBN 971-8711-06-6

- Aguinaldo y Famy, Emilio (1899), "Chapter II. The Treaty of Biak-na-bató", True Version of the Philippine Revolution, Authorama: Public Domain Books, retrieved 7 February 2008

- Aguinaldo y Famy, Emilio (1899), "Chapter III. Negotiations", True Version of the Philippine Revolution, Authorama: Public Domain Books, retrieved 26 December 2007

- Alvarez, S.V. (1992), Recalling the Revolution, Madison: Center for Southeast Asia Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison, ISBN 1-881261-05-0

- Alvarez, Santiago V.; Malay, Paula Carolina S. (1992), The katipunan and the revolution: memoirs of a general: with the original Tagalog text, Ateneo de Manila University Press, ISBN 978-971-550-077-7, Translated by Paula Carolina S. Malay

- Anderson, Benedict (2005), Under Three Flags: Anarchism and the Anti-Colonial Imagination, London: Verso, ISBN 1-84467-037-6

- Batchelor, Bob (2002), The 1900s : American popular culture through history, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-313-31334-9

- Blanchard, William H. (1996), Neocolonialism American Style, 1960–2000 (illustrated ed.), Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-313-30013-4

- Blair, Emma; Robertson, James (1903–1909), The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898, 1–55, Cleveland

- Bowring, Sir John (1859), A Visit to the Philippine Islands, London: Smith, Elder and Co.

- Constantino, Renato (1975), The Philippines: A Past Revisited, Self-published, Tala Pub. Services

- de Moya, Francisco Javier (1883), Las Islas Filipinas en 1882 (in Spanish), 1–55, Madrid

- Dav, Chaitanya (2007), Crimes Against Humanity: A Shocking History of U.s. Crimes Since 1776, AuthorHouse, ISBN 978-1-4343-0181-9

- Díaz Arenas, Rafaél (1838), Memoria sobre el comercio y navegacion de las islas Filipinas (in Spanish), Cádiz, Spain

- Foreman, J. (1906), The Philippine Islands: A Political, Geographical, Ethnographical, Social, and Commercial History of the Philippine Archipelago, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons

- Gatbonton, Esperanza B., ed. (2000), The Philippines After The Revolution 1898–1945, National Commission for Culture and the Arts, ISBN 971-814-004-2

- Custodio, Teresa Ma; Dalisay, Jose Y. (1998), "Reform and Revolution", Kasaysayan: The History of the Filipino People, 5, Asia Publishing Company Limited, ISBN 962-258-228-1

- Guevara, Sulpico, ed. (2005), The laws of the first Philippine Republic (the laws of Malolos) 1898–1899, Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Library (published 1972), retrieved 26 March 2008 (English translation by Sulpicio Guevara)

- Halili, Maria Christine N. (2004), Philippine History, Manila: Rex Book Store, ISBN 978-971-23-3934-9

- Halstead, Murat (1898), "XII. The American Army in Manila", The Story of the Philippines and Our New Possessions, Including the Ladrones, Hawaii, Cuba and Porto Rico

- Jagor, Feodor (1873), Weidmannsche Buchhandlung (in German), Berlin. An English translation under the title Travels in the Philippines was printed in London, 1875, by Chapman and Hall.

- Kalaw, Maximo Manguiat (1927), The Development of Philippine Politics, Oriental commercial, retrieved 7 February 2008

- Keat, Gin Ooi (2004), Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor, Volume 1, BC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-57607-770-2

- Mabini, Apolinario (1969), "CHAPTER VIII: First Stage of the Revolution", in Guerrero, Leon Ma. (ed.), The Philippine Revolution, National Historical Commission, Translated by Leon Ma. Guerrero.

- Lone, Stewart (2007). Daily Lives of Civilians in Wartime Asia: From the Taiping Rebellion to the Vietnam War. Life Through History Series: Daily Lives of Civilians during Wartime. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-33684-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Montero y Vidal, Jose (1887–1895), Historia general de Filipinas (in Spanish), 1–3, Madrid: Imprenta de Manuel Tello

- Nelson-Pallmeyer, Jack (2005), Saving Christianity from empire, Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-8264-1627-8

- Regidor, Antonio M.; Mason, J. Warren (1905), Commercial Progress in the Philippine Islands, London: Dunn & Chidley

- Rodao, Florentino; Rodríguez, Felice Noelle (2001), The Philippine revolution of 1896: ordinary lives in extraordinary times, Ateneo de Manila University Press, ISBN 978-971-550-386-0

- Salazar, Zeus (1994), Agosto 29-30, 1896: ang pagsalakay ni Bonifacio sa Maynila, Quezon City: Miranda Bookstore

- Seekins, Donald M. (1991), "Historical Setting—Outbreak of War, 1898", in Seekins, Dolan (ed.), Philippines: A Country Study, Washington: Library of Congress, retrieved 25 December 2007

- Sagmit, Rosario S.; Sagmit-Mendosa, Lourdes (2007), The Filipino Moving Onward 5, Rex Bookstore, Inc., ISBN 978-971-23-4154-0

- Schumacher, John N. (1991), The Making of a Nation: Essays on Nineteenth-century Filipino Nationalism, Ateneo de Manila University Press, ISBN 978-971-550-019-7

- Titherington, Richard Handfield (1900), A history of the Spanish–American War of 1898, D. Appleton and Company

- Worcester, Dean Conant (1914), The Philippines: Past and Present (vol. 1 of 2), Macmillan, pp. 75–89, ISBN 1-4191-7715-X, retrieved 7 February 2008

- Zaide, Gregorio (1954), The Philippine Revolution, Manila: The Modern Book Company

- Zaide, Gregorio F. (1957), Philippine Political and Cultural History: The Philippines Since the British Invasion, II (1957 Revised ed.), Manila: McCullough Printing Company

External links

- Don Emilio Aguinaldo y Famy. "True Version of the Philippine Revolution". Authorama Public Domain Books. Retrieved 16 November 2007. (page 1 of 20 linked web pages)

- Hisona, Harold T. "Opening of Manila to World Trade". Philippine Almanac. Archived from the original on 2012-03-21. Retrieved 2011-08-27.

- Coats, Steven D. (2006). "Gathering at the Golden Gate: Mobilizing for War in the Philippines, 1898". Combat studies Institute Press. Part 1 (Ch. I–IV), Part 2 (Ch. V–VIII).

- The Philippine Revolution by Apolinario Mabini

- Centennial Site: The Katipunan

- Leon Kilat covers the Revolution in Cebu (archived from the original on October 26, 2009)

- Another site on the Revolution (archived from the original on October 13, 2007)