German language

German (Deutsch, pronounced [dɔʏtʃ] (![]()

| German | |

|---|---|

| Deutsch | |

| Pronunciation | [dɔʏtʃ] |

| Native to | German-speaking Europe |

| Region | Germany, Austria and Switzerland |

| Ethnicity | German-speaking peoples

|

Native speakers | 90 million (2010) to 95 million (2014) L2 speakers: 10–15 million (2014)[1] |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | |

Standard forms |

Austrian Standard German

|

| Latin (German alphabet) German Braille | |

| Signed German, LBG (Lautsprachbegleitende / Lautbegleitende Gebärden) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

Several international institutions |

Recognised minority language in |

|

| Regulated by | No official regulation (German orthography regulated by the Council for German Orthography)[2] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | de |

| ISO 639-2 | ger (B) deu (T) |

| ISO 639-3 | Variously:deu – Germangmh – Middle High Germangoh – Old High Germangct – Colonia Tovar Germanbar – Bavariancim – Cimbriangeh – Hutterite Germanksh – Kölschnds – Low German[note 1]sli – Lower Silesianltz – Luxembourgish[note 2]vmf – Mainfränkischmhn – Mòchenopfl – Palatinate Germanpdc – Pennsylvania Germanpdt – Plautdietsch[note 3]swg – Swabian Germangsw – Swiss Germanuln – Unserdeutschsxu – Upper Saxonwae – Walser Germanwep – Westphalianhrx – Riograndenser Hunsrückischyec – Yenish |

| Glottolog | high1287 High Franconian[4]uppe1397 Upper German[5] |

| Linguasphere | |

(Co-)Official and majority language

Co-official, but not majority language

Statutory minority/cultural language

Non-statutory minority language | |

One of the major languages of the world, German is a native language to almost 100 million people worldwide and the most widely spoken native language in the European Union.[6] German is the third most commonly spoken foreign language in the EU after English and French, making it the second biggest language in the EU in terms of overall speakers. German is also the second most widely taught foreign language in the EU after English at primary school level (but third after English and French at lower secondary level), the fourth most widely taught non-English language in the US (after Spanish, French and American Sign Language), the second most commonly used scientific language and the third most widely used language on websites after English and Russian. The German-speaking countries are ranked fifth in terms of annual publication of new books, with one tenth of all books (including e-books) in the world being published in German. In the United Kingdom, German and French are the most sought-after foreign languages for businesses (with 49% and 50% of businesses identifying these two languages as the most useful, respectively).[7]

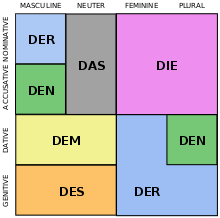

German is an inflected language with four cases for nouns, pronouns and adjectives (nominative, accusative, genitive, dative), three genders (masculine, feminine, neuter), two numbers (singular, plural), and strong and weak verbs. It derives the majority of its vocabulary from the ancient Germanic branch of the Indo-European language family. Some of its vocabulary is derived from Latin and Greek, and fewer are borrowed from French and Modern English. German is a pluricentric language, with its standardized variants being (German, Austrian, and Swiss Standard German). It is also notable for its broad spectrum of dialects, with many unique varieties existing in Europe and other parts of the world. Italy recognizes all the German-speaking minorities in its territory as national historic minorities and protects the varieties of German spoken in several regions of Northern Italy besides South Tyrol.[8][9] Due to the limited intelligibility between certain varieties and Standard German, as well as the lack of an undisputed, scientific difference between a "dialect" and a "language", some German varieties or dialect groups (e.g. Low German or Plautdietsch[3]) can be described as either "languages" or "dialects".

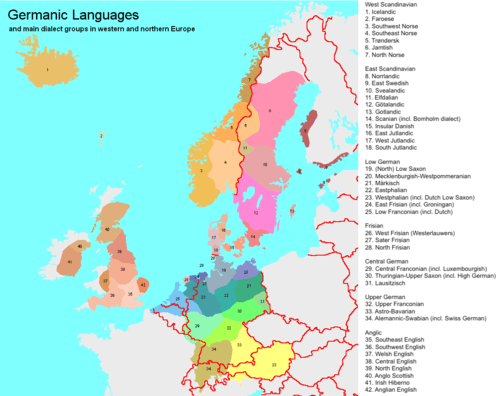

Classification

Modern Standard German is a West Germanic language in the Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages. The Germanic languages are traditionally subdivided into three branches: North Germanic, East Germanic, and West Germanic. The first of these branches survives in modern Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Faroese, and Icelandic, all of which are descended from Old Norse. The East Germanic languages are now extinct, and Gothic is the only language in this branch which survives in written texts. The West Germanic languages, however, have undergone extensive dialectal subdivision and are now represented in modern languages such as English, German, Dutch, Yiddish, Afrikaans, and others.[10]

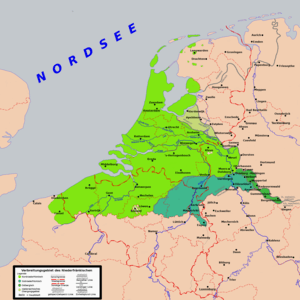

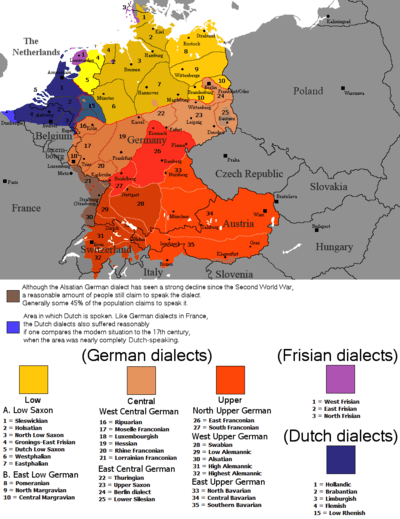

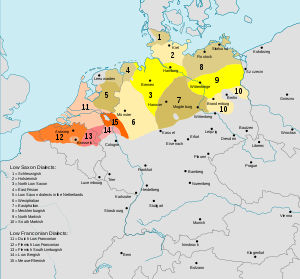

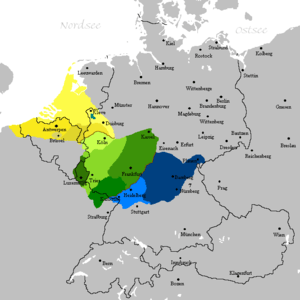

Within the West Germanic language dialect continuum, the Benrath and Uerdingen lines (running through Düsseldorf-Benrath and Krefeld-Uerdingen, respectively) serve to distinguish the Germanic dialects that were affected by the High German consonant shift (south of Benrath) from those that were not (north of Uerdingen). The various regional dialects spoken south of these lines are grouped as High German dialects (nos. 29–34 on the map), while those spoken to the north comprise the Low German/Low Saxon (nos. 19–24) and Low Franconian (no. 25) dialects. As members of the West Germanic language family, High German, Low German, and Low Franconian can be further distinguished historically as Irminonic, Ingvaeonic, and Istvaeonic, respectively. This classification indicates their historical descent from dialects spoken by the Irminones (also known as the Elbe group), Ingvaeones (or North Sea Germanic group), and Istvaeones (or Weser-Rhine group).[10]

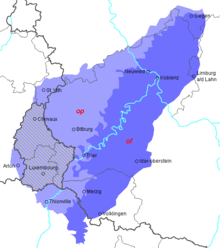

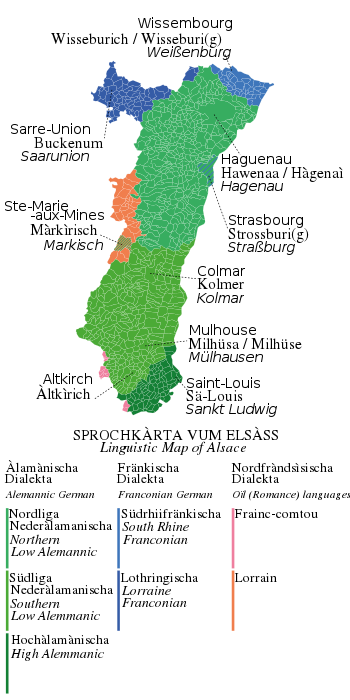

Standard German is based on a combination of Thuringian-Upper Saxon and Upper Franconian and Bavarian dialects, which are Central German and Upper German dialects, belonging to the Irminonic High German dialect group (nos. 29–34). German is therefore closely related to the other languages based on High German dialects, such as Luxembourgish (based on Central Franconian dialects – no. 29), and Yiddish. Also closely related to Standard German are the Upper German dialects spoken in the southern German-speaking countries, such as Swiss German (Alemannic dialects – no. 34), and the various Germanic dialects spoken in the French region of Grand Est, such as Alsatian (mainly Alemannic, but also Central- and Upper Franconian (no. 32) dialects) and Lorraine Franconian (Central Franconian – no. 29).

After these High German dialects, standard German is less closely related to languages based on Low Franconian dialects (e.g. Dutch and Afrikaans) or Low German/Low Saxon dialects (spoken in northern Germany and southern Denmark), neither of which underwent the High German consonant shift. As has been noted, the former of these dialect types is Istvaeonic and the latter Ingvaeonic, whereas the High German dialects are all Irminonic: the differences between these languages and standard German are therefore considerable. Also related to German are the Frisian languages—North Frisian (spoken in Nordfriesland – no. 28), Saterland Frisian (spoken in Saterland – no. 27), and West Frisian (spoken in Friesland – no. 26)—as well as the Anglic languages of English and Scots. These Anglo-Frisian dialects are all members of the Ingvaeonic family of West Germanic languages, which did not take part in the High German consonant shift.

History

Old High German

The history of the German language begins with the High German consonant shift during the migration period, which separated Old High German (OHG) dialects from Old Saxon. This sound shift involved a drastic change in the pronunciation of both voiced and voiceless stop consonants (b, d, g, and p, t, k, respectively). The primary effects of the shift were the following:

- Voiceless stops became long (geminated) voiceless fricatives following a vowel;

- Voiceless stops became affricates in word-initial position, or following certain consonants;

- Voiced stops became voiceless in certain phonetic settings.[11]

| Voiceless stop following a vowel |

Word-initial voiceless stop |

Voiced stop |

|---|---|---|

| /p/→/ff/ | /p/→/pf/ | /b/→/p/ |

| /t/→/ss/ | /t/→/ts/ | /d/→/t/ |

| /k/→/xx/ | /k/→/kx/ | /g/→/k/ |

While there is written evidence of the Old High German language in several Elder Futhark inscriptions from as early as the 6th century AD (such as the Pforzen buckle), the Old High German period is generally seen as beginning with the Abrogans (written c.765–775), a Latin-German glossary supplying over 3,000 OHG words with their Latin equivalents. After the Abrogans, the first coherent works written in OHG appear in the 9th century, chief among them being the Muspilli, the Merseburg Charms, and the Hildebrandslied, as well as a number of other religious texts (the Georgslied, the Ludwigslied, the Evangelienbuch, and translated hymns and prayers).[11][12] The Muspilli is a Christian poem written in a Bavarian dialect offering an account of the soul after the Last Judgment, and the Merseburg Charms are transcriptions of spells and charms from the pagan Germanic tradition. Of particular interest to scholars, however, has been the Hildebrandslied, a secular epic poem telling the tale of an estranged father and son unknowingly meeting each other in battle. Linguistically this text is highly interesting due to the mixed use of Old Saxon and Old High German dialects in its composition. The written works of this period stem mainly from the Alamanni, Bavarian, and Thuringian groups, all belonging to the Elbe Germanic group (Irminones), which had settled in what is now southern-central Germany and Austria between the 2nd and 6th centuries during the great migration.[11]

In general, the surviving texts of OHG show a wide range of dialectal diversity with very little written uniformity. The early written tradition of OHG survived mostly through monasteries and scriptoria as local translations of Latin originals; as a result, the surviving texts are written in highly disparate regional dialects and exhibit significant Latin influence, particularly in vocabulary.[11] At this point monasteries, where most written works were produced, were dominated by Latin, and German saw only occasional use in official and ecclesiastical writing.

The German language through the OHG period was still predominantly a spoken language, with a wide range of dialects and a much more extensive oral tradition than a written one. Having just emerged from the High German consonant shift, OHG was also a relatively new and volatile language still undergoing a number of phonetic, phonological, morphological, and syntactic changes. The scarcity of written work, instability of the language, and widespread illiteracy of the time explain the lack of standardization up to the end of the OHG period in 1050.

Middle High German

While there is no complete agreement over the dates of the Middle High German (MHG) period, it is generally seen as lasting from 1050 to 1350.[13][14] This was a period of significant expansion of the geographical territory occupied by Germanic tribes, and consequently of the number of German speakers. Whereas during the Old High German period the Germanic tribes extended only as far east as the Elbe and Saale rivers, the MHG period saw a number of these tribes expanding beyond this eastern boundary into Slavic territory (known as the Ostsiedlung). With the increasing wealth and geographic spread of the Germanic groups came greater use of German in the courts of nobles as the standard language of official proceedings and literature.[14][15] A clear example of this is the mittelhochdeutsche Dichtersprache employed in the Hohenstaufen court in Swabia as a standardized supra-dialectal written language. While these efforts were still regionally bound, German began to be used in place of Latin for certain official purposes, leading to a greater need for regularity in written conventions.

While the major changes of the MHG period were socio-cultural, German was still undergoing significant linguistic changes in syntax, phonetics, and morphology as well (e.g. diphthongization of certain vowel sounds: hus (OHG "house")→haus (MHG), and weakening of unstressed short vowels to schwa [ə]: taga (OHG "days")→tage (MHG)).[16]

A great wealth of texts survives from the MHG period. Significantly, these texts include a number of impressive secular works, such as the Nibelungenlied, an epic poem telling the story of the dragon-slayer Siegfried (c. 13th century), and the Iwein, an Arthurian verse poem by Hartmann von Aue (c. 1203), as well as several lyric poems and courtly romances such as Parzival and Tristan. Also noteworthy is the Sachsenspiegel, the first book of laws written in Middle Low German (c. 1220). The abundance and especially the secular character of the literature of the MHG period demonstrate the beginnings of a standardized written form of German, as well as the desire of poets and authors to be understood by individuals on supra-dialectal terms.

The Middle High German period is generally seen as ending when the 1346-53 Black Death decimated Europe's population.[13]

Early New High German

.png)

Modern German begins with the Early New High German (ENHG) period, which the influential German philologist Wilhelm Scherer dates 1350–1650, terminating with the end of the Thirty Years' War.[13] This period saw the further displacement of Latin by German as the primary language of courtly proceedings and, increasingly, of literature in the German states. While these states were still under the control of the Holy Roman Empire and far from any form of unification, the desire for a cohesive written language that would be understandable across the many German-speaking principalities and kingdoms was stronger than ever. As a spoken language German remained highly fractured throughout this period, with a vast number of often mutually incomprehensible regional dialects being spoken throughout the German states; the invention of the printing press c. 1440 and the publication of Luther's vernacular translation of the Bible in 1534, however, had an immense effect on standardizing German as a supra-dialectal written language.

The ENHG period saw the rise of several important cross-regional forms of chancery German, one being gemeine tiutsch, used in the court of the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, and the other being Meißner Deutsch, used in the Electorate of Saxony in the Duchy of Saxe-Wittenberg.[17] Alongside these courtly written standards, the invention of the printing press led to the development of a number of printers' languages (Druckersprachen) aimed at making printed material readable and understandable across as many diverse dialects of German as possible.[18] The greater ease of production and increased availability of written texts brought about increased standardization in the written form of German.

One of the central events in the development of ENHG was the publication of Luther's translation of the Bible into German (the New Testament was published in 1522; the Old Testament was published in parts and completed in 1534). Luther based his translation primarily on the Meißner Deutsch of Saxony, spending much time among the population of Saxony researching the dialect so as to make the work as natural and accessible to German speakers as possible. Copies of Luther's Bible featured a long list of glosses for each region, translating words which were unknown in the region into the regional dialect. Luther said the following concerning his translation method:

One who would talk German does not ask the Latin how he shall do it; he must ask the mother in the home, the children on the streets, the common man in the market-place and note carefully how they talk, then translate accordingly. They will then understand what is said to them because it is German. When Christ says 'ex abundantia cordis os loquitur,' I would translate, if I followed the papists, aus dem Überflusz des Herzens redet der Mund. But tell me is this talking German? What German understands such stuff? No, the mother in the home and the plain man would say, Wesz das Herz voll ist, des gehet der Mund über.[19]

With Luther's rendering of the Bible in the vernacular, German asserted itself against the dominance of Latin as a legitimate language for courtly, literary, and now ecclesiastical subject-matter. Furthermore, his Bible was ubiquitous in the German states: nearly every household possessed a copy.[20] Nevertheless, even with the influence of Luther's Bible as an unofficial written standard, a widely accepted standard for written German did not appear until the middle of the 18th century.[21]

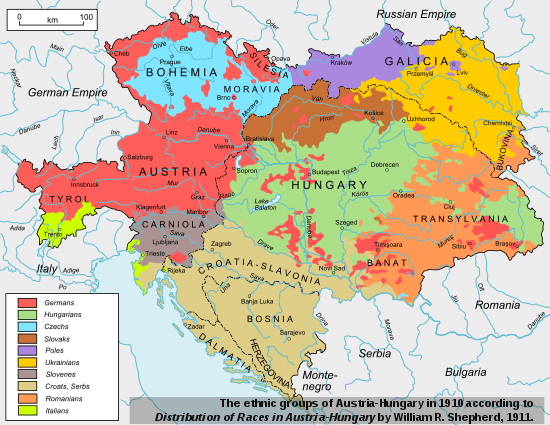

Austrian Empire

German was the language of commerce and government in the Habsburg Empire, which encompassed a large area of Central and Eastern Europe. Until the mid-19th century, it was essentially the language of townspeople throughout most of the Empire. Its use indicated that the speaker was a merchant or someone from an urban area, regardless of nationality.

Some cities, such as Prague (German: Prag) and Budapest (Buda, German: Ofen), were gradually Germanized in the years after their incorporation into the Habsburg domain. Others, such as Pozsony (German: Pressburg, now Bratislava), were originally settled during the Habsburg period and were primarily German at that time. Prague, Budapest and Bratislava, as well as cities like Zagreb (German: Agram) and Ljubljana (German: Laibach), contained significant German minorities.

In the eastern provinces of Banat, Bukovina, and Transylvania (German: Banat, Buchenland, Siebenbürgen), German was the predominant language not only in the larger towns – such as Temeschburg (Timișoara), Hermannstadt (Sibiu) and Kronstadt (Brașov) – but also in many smaller localities in the surrounding areas.[22]

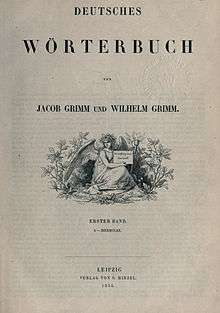

Standardization

The most comprehensive guide to the vocabulary of the German language is found within the Deutsches Wörterbuch. This dictionary was created by the Brothers Grimm and is composed of 16 parts which were issued between 1852 and 1860.[23] In 1872, grammatical and orthographic rules first appeared in the Duden Handbook.[24]

In 1901, the 2nd Orthographical Conference ended with a complete standardization of the German language in its written form and the Duden Handbook was declared its standard definition.[25] The Deutsche Bühnensprache (literally, German stage language) had established conventions for German pronunciation in theatres (Bühnendeutsch[26]) three years earlier; however, this was an artificial standard that did not correspond to any traditional spoken dialect. Rather, it was based on the pronunciation of Standard German in Northern Germany, although it was subsequently regarded often as a general prescriptive norm, despite differing pronunciation traditions especially in the Upper-German-speaking regions that still characterize the dialect of the area today – especially the pronunciation of the ending -ig as [ɪk] instead of [ɪç]. In Northern Germany, Standard German was a foreign language to most inhabitants, whose native dialects were subsets of Low German. It was usually encountered only in writing or formal speech; in fact, most of Standard German was a written language, not identical to any spoken dialect, throughout the German-speaking area until well into the 19th century.

Official revisions of some of the rules from 1901 were not issued until the controversial German orthography reform of 1996 was made the official standard by governments of all German-speaking countries.[27] Media and written works are now almost all produced in Standard German (often called Hochdeutsch, "High German") which is understood in all areas where German is spoken.

Geographic distribution

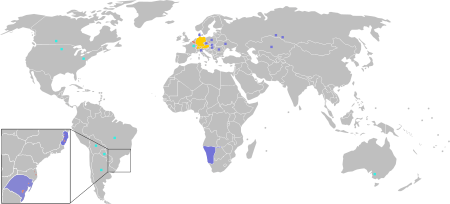

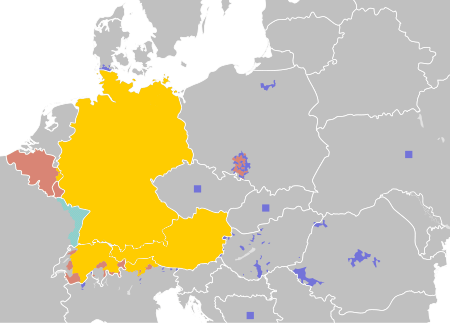

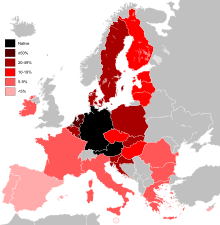

Approximate distribution of native German speakers (assuming a rounded total of 95 million) worldwide

Due to the German diaspora as well as German being the second most widely spoken language in Europe and the third most widely taught foreign language in the US[28] and the EU (in upper secondary education)[29] amongst others, the geographical distribution of German speakers (or "Germanophones") spans all inhabited continents. As for the number of speakers of any language worldwide, an assessment is always compromised by the lack of sufficient, reliable data. For an exact, global number of native German speakers, this is further complicated by the existence of several varieties whose status as separate "languages" or "dialects" is disputed for political and/or linguistic reasons, including quantitatively strong varieties like certain forms of Alemannic (e.g., Alsatian) and Low German/Plautdietsch.[3] Depending on the inclusion or exclusion of certain varieties, it is estimated that approximately 90–95 million people speak German as a first language,[30][31] 10–25 million as a second language,[30] and 75–100 million as a foreign language.[1] This would imply the existence of approximately 175–220 million German speakers worldwide.[32] It is estimated that including every person studying German, regardless of their actual proficiency, would amount to about 280 million people worldwide with at least some knowledge of German.

Europe and Asia

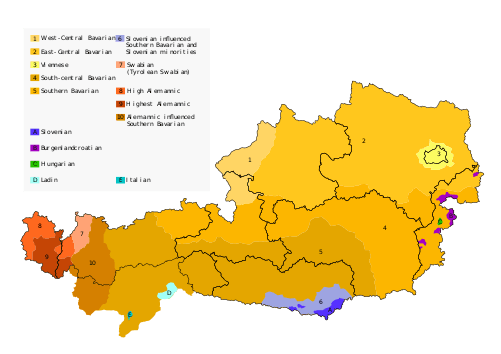

German Sprachraum

In Europe, German is the second most widely spoken mother tongue (after Russian) and the second biggest language in terms of overall speakers (after English). The area in central Europe where the majority of the population speaks German as a first language and has German as a (co-)official language is called the "German Sprachraum". It comprises an estimated 88 million native speakers and 10 million who speak German as a second language (e.g. immigrants).[30] Excluding regional minority languages, German is the only official language of the following countries:

- Germany (de facto, not specified in the constitution);

- Austria (de jure);

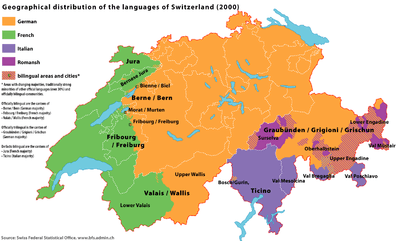

- 17 cantons of Switzerland (de jure);

- Liechtenstein (de jure).

German is a co-official language of the following countries:

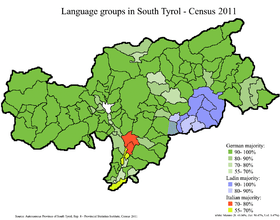

- Italian Autonomous Province of South Tyrol (also majority language);

- Belgium (as majority language only in the German-speaking Community);

- four cantons of Switzerland (majority language in certain areas of these);

- Luxembourg.

Outside the Sprachraum

Although expulsions and (forced) assimilation after the two World Wars greatly diminished them, minority communities of mostly bilingual German native speakers exist in areas both adjacent to and detached from the Sprachraum.

Within Europe and Asia, German is a recognized minority language in the following countries:

- Bosnia and Herzegovina[33] (see also: Donauschwaben)

- Czech Republic[33] (see also: Germans in the Czech Republic)

- Denmark[33] (see also: North Schleswig Germans)

- Hungary[33] (see also: Germans of Hungary)

- Italy[34] (outside of South Tyrol; see also: Cimbrian, Mòcheno/Fersentalerisch, Walser German)

- Kazakhstan[35][36] (see also: Germans of Kazakhstan)

- Poland[33] (see also German minority in Poland; German is an auxiliary language in 31 communes[37])

- Romania[33] (see also: Germans of Romania)

- Russia[38] (see also: Germans in Russia)

- Slovakia[33] (see also: Carpathian Germans)

- Ukraine[33] (see also: Germans in Ukraine)

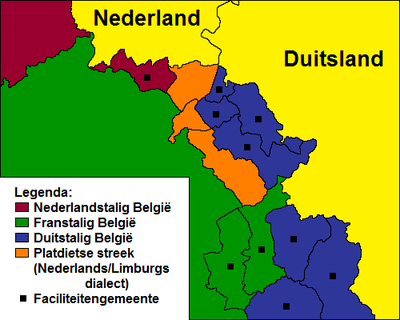

In France, the High German varieties of Alsatian and Moselle Franconian are identified as "regional languages", but the European Charter for Regional and Minority Languages of 1998 has not yet been ratified by the government.[39] In the Netherlands, the Limburgish, Frisian, and Low German languages are protected regional languages according to the European Charter for Regional and Minority Languages;[33] however, they are widely considered separate languages and neither German nor Dutch dialects.

Africa

Namibia

Namibia was a colony of the German Empire from 1884 to 1919. Mostly descending from German settlers who immigrated during this time, 25–30,000 people still speak German as a native tongue today.[40] The period of German colonialism in Namibia also led to the evolution of a Standard German-based pidgin language called "Namibian Black German", which became a second language for parts of the indigenous population. Although it is nearly extinct today, some older Namibians still have some knowledge of it.[41]

German, along with English and Afrikaans, was a co-official language of Namibia from 1984 until its independence from South Africa in 1990. At this point, the Namibian government perceived Afrikaans and German as symbols of apartheid and colonialism, and decided English would be the sole official language, stating that it was a "neutral" language as there were virtually no English native speakers in Namibia at that time.[40] German, Afrikaans and several indigenous languages became "national languages" by law, identifying them as elements of the cultural heritage of the nation and ensuring that the state acknowledged and supported their presence in the country. Today, German is used in a wide variety of spheres, especially business and tourism, as well as the churches (most notably the German-speaking Evangelical Lutheran Church in Namibia (GELK)), schools (e.g. the Deutsche Höhere Privatschule Windhoek), literature (German-Namibian authors include Giselher W. Hoffmann), radio (the Namibian Broadcasting Corporation produces radio programs in German), and music (e.g. artist EES). The Allgemeine Zeitung is one of the three biggest newspapers in Namibia and the only German-language daily in Africa.[40]

South Africa

Mostly originating from different waves of immigration during the 19th and 20th centuries, an estimated 12,000 people speak German or a German variety as a first language in South Africa.[42] One of the largest communities consists of the speakers of "Nataler Deutsch",[43] a variety of Low German concentrated in and around Wartburg. The small town of Kroondal in the North-West Province also has a mostly German-speaking population. The South African constitution identifies German as a "commonly used" language and the Pan South African Language Board is obligated to promote and ensure respect for it.[44] The community is strong enough that several German International schools are supported, such as the Deutsche Schule Pretoria.

North America

In the United States, the states of North Dakota and South Dakota are the only states where German is the most common language spoken at home after English.[45] German geographical names can be found throughout the Midwest region of the country, such as New Ulm and many other towns in Minnesota; Bismarck (North Dakota's state capital), Munich, Karlsruhe, and Strasburg (named after a town near Odessa in Ukraine)[46] in North Dakota; New Braunfels, Fredericksburg, Weimar, and Muenster in Texas; Corn (formerly Korn), Kiefer and Berlin in Oklahoma; and Kiel, Berlin, and Germantown in Wisconsin.

South America

Brazil

In Brazil, the largest concentrations of German speakers are in the states of Rio Grande do Sul (where Riograndenser Hunsrückisch developed), Santa Catarina, Paraná, São Paulo and Espírito Santo.[47]

Co-official statuses of German in Brazil

- Espírito Santo (statewide cultural language)[47][48][49][50]

- Rio Grande do Sul (Riograndenser Hunsrückisch German is an integral part of the historical and cultural heritage of this state)[53][47]

- Santa Catarina[47]

Other South American countries

- Main articles: Colonia Tovar dialect, Chilean German

There are important concentrations of German-speaking descendants in Argentina, Chile, Paraguay, Venezuela, Peru, and Bolivia.[42]

The impact of nineteenth century German immigration to southern Chile was such that Valdivia was for a while a Spanish-German bilingual city with "German signboards and placards alongside the Spanish".[54] The prestige[note 4] the German language caused it to acquire qualities of a superstratum in southern Chile.[56] The word for blackberry, a ubiquitous plant in southern Chile, is murra, instead of the ordinary Spanish words mora and zarzamora, from Valdivia to the Chiloé Archipelago and in some towns in the Aysén Region.[56] The use of rr is an adaptation of guttural sounds found in German but difficult to pronounce in Spanish.[56] Similarly the name for marbles, a traditional children's game, is different in Southern Chile compared to areas further north. From Valdivia to the Aysén Region this game is called bochas, in contrast to the word bolitas used further north.[56] The word bocha is likely a derivative of the German Bocciaspiel.[56]

Oceania

In Australia, the state of South Australia experienced a pronounced wave of immigration in the 1840s from Prussia (particularly the Silesia region). With the prolonged isolation from other German speakers and contact with Australian English, a unique dialect known as Barossa German developed, spoken predominantly in the Barossa Valley near Adelaide. Usage of German sharply declined with the advent of World War I, due to the prevailing anti-German sentiment in the population and related government action. It continued to be used as a first language into the 20th century, but its use is now limited to a few older speakers.[57]

German migration to New Zealand in the 19th century was less pronounced than migration from Britain, Ireland, and perhaps even Scandinavia. Despite this there were significant pockets of German-speaking communities which lasted until the first decades of the 20th century. German speakers settled principally in Puhoi, Nelson, and Gore. At the last census (2013), 36,642 people in New Zealand spoke German, making it the third most spoken European language after English and French and overall the ninth most spoken language.[58]

There is also an important German creole being studied and recovered, named Unserdeutsch, spoken in the former German colony of German New Guinea, across Micronesia and in northern Australia (i.e. coastal parts of Queensland and Western Australia) by a few elderly people. The risk of its extinction is serious and efforts to revive interest in the language are being implemented by scholars.[59]

German as a foreign language

Like French and Spanish, German has become a standard second foreign language in the western world.[1][60] German ranks second (after English) among the best known foreign languages in the EU (on a par with French)[1] as well as in Russia.[61] In terms of student numbers across all levels of education, German ranks third in the EU (after English and French)[29] as well as in the United States (after Spanish and French).[28][62] In 2015, approximately 15.4 million people were in the process of learning German across all levels of education worldwide.[60] As this number remained relatively stable since 2005 (± 1 million), roughly 75–100 million people able to communicate in German as a foreign language can be inferred, assuming an average course duration of three years and other estimated parameters. According to a 2012 survey, 47 million people within the EU (i.e., up to two-thirds of the 75–100 million worldwide) claimed to have sufficient German skills to have a conversation. Within the EU, not counting countries where it is an official language, German as a foreign language is most popular in Eastern and northern Europe, namely the Czech Republic, Croatia, Denmark, the Netherlands, Slovakia, Hungary, Slovenia, Sweden and Poland.[1][63] German was once, and to some extent still is, a lingua franca in those parts of Europe.[64]

Standard German

The basis of Standard German is the Luther Bible, which was translated by Martin Luther and which had originated from the Saxon court language (it being a convenient norm).[65] However, there are places where the traditional regional dialects have been replaced by new vernaculars based on standard German; that is the case in large stretches of Northern Germany but also in major cities in other parts of the country. It is important to note, however, that the colloquial standard German differs greatly from the formal written language, especially in grammar and syntax, in which it has been influenced by dialectal speech.

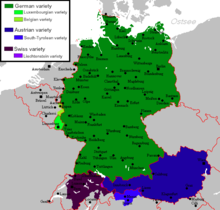

Standard German differs regionally among German-speaking countries in vocabulary and some instances of pronunciation and even grammar and orthography. This variation must not be confused with the variation of local dialects. Even though the regional varieties of standard German are only somewhat influenced by the local dialects, they are very distinct. German is thus considered a pluricentric language.

In most regions, the speakers use a continuum from more dialectal varieties to more standard varieties depending on the circumstances.

Varieties of Standard German

In German linguistics, German dialects are distinguished from varieties of standard German. The varieties of standard German refer to the different local varieties of the pluricentric standard German. They differ only slightly in lexicon and phonology. In certain regions, they have replaced the traditional German dialects, especially in Northern Germany.

- German Standard German

- Austrian Standard German

- Swiss Standard German

In the German-speaking parts of Switzerland, mixtures of dialect and standard are very seldom used, and the use of Standard German is largely restricted to the written language. About 11% of the Swiss residents speak High German (Standard German) at home, but this is mainly due to German immigrants.[67] This situation has been called a medial diglossia. Swiss Standard German is used in the Swiss education system, while Austrian Standard German is officially used in the Austrian education system.

A mixture of dialect and standard does not normally occur in Northern Germany either. The traditional varieties there are Low German, whereas Standard German is a High German "variety". Because their linguistic distance is greater, they do not mesh with Standard German the way that High German dialects (such as Bavarian, Swabian, and Hessian) can.

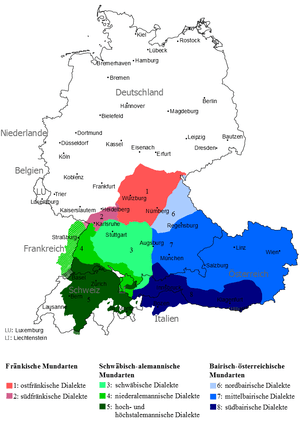

Dialects

The German dialects are the traditional local varieties of the language; many of them are not mutually intelligibile with standard German, and they have great differences in lexicon, phonology, and syntax. If a narrow definition of language based on mutual intelligibility is used, many German dialects are considered to be separate languages (for instance in the Ethnologue). However, such a point of view is unusual in German linguistics.

The German dialect continuum is traditionally divided most broadly into High German and Low German, also called Low Saxon. However, historically, High German dialects and Low Saxon/Low German dialects do not belong to the same language. Nevertheless, in today's Germany, Low Saxon/Low German is often perceived as a dialectal variation of Standard German on a functional level even by many native speakers. The same phenomenon is found in the eastern Netherlands, as the traditional dialects are not always identified with their Low Saxon/Low German origins, but with Dutch.[68]

The variation among the German dialects is considerable, with often only neighbouring dialects being mutually intelligible. Some dialects are not intelligible to people who know only Standard German. However, all German dialects belong to the dialect continuum of High German and Low Saxon.

Low German and Low Saxon

Middle Low German was the lingua franca of the Hanseatic League. It was the predominant language in Northern Germany until the 16th century. In 1534, the Luther Bible was published. The translation is considered to be an important step towards the evolution of the Early New High German. It aimed to be understandable to a broad audience and was based mainly on Central and Upper German varieties. The Early New High German language gained more prestige than Low German and became the language of science and literature. Around the same time, the Hanseatic League, based around northern ports, lost its importance as new trade routes to Asia and the Americas were established, and the most powerful German states of that period were located in Middle and Southern Germany.

The 18th and 19th centuries were marked by mass education in Standard German in schools. Gradually, Low German came to be politically viewed as a mere dialect spoken by the uneducated. Today, Low Saxon can be divided in two groups: Low Saxon varieties with a reasonable level of Standard German influence and varieties of Standard German with a Low Saxon influence known as Missingsch. Sometimes, Low Saxon and Low Franconian varieties are grouped together because both are unaffected by the High German consonant shift. However, the proportion of the population who can understand and speak it has decreased continuously since World War II. The largest cities in the Low German area are Hamburg and Dortmund.

Low Franconian

The Low Franconian dialects are the dialects that are more closely related to Dutch than to Low German. Most of the Low Franconian dialects are spoken in the Netherlands and Belgium, where they are considered as dialects of Dutch, which is itself a Low Franconian language. In Germany, Low Franconian dialects are spoken in the northwest of North Rhine-Westphalia, along the Lower Rhine. The Low Franconian dialects spoken in Germany are referred to as Meuse-Rhenish or Low Rhenish. In the north of the German Low Franconian language area, North Low Franconian dialects (also referred to as Cleverlands or as dialects of South Guelderish) are spoken. These dialects are more closely related to Dutch (also North Low Franconian) than the South Low Franconian dialects (also referred to as East Limburgish and, east of the Rhine, Bergish), which are spoken in the south of the German Low Franconian language area. The South Low Franconian dialects are more closely related to Limburgish than to Dutch, and are transitional dialects between Low Franconian and Ripuarian (Central Franconian). The East Bergish dialects are the easternmost Low Franconian dialects, and are transitional dialects between North- and South Low Franconian, and Westphalian (Low German), with most of their features being North Low Franconian. The largest cities in the German Low Franconian area are Düsseldorf and Duisburg.

High German

The High German dialects consist of the Central German, High Franconian, and Upper German dialects. The High Franconian dialects are transitional dialects between Central and Upper German. The High German varieties spoken by the Ashkenazi Jews have several unique features and are considered as a separate language, Yiddish, written with the Hebrew alphabet.

Central German

The Central German dialects are spoken in Central Germany, from Aachen in the west to Görlitz in the east. They consist of Franconian dialects in the west (West Central German) and non-Franconian dialects in the east (East Central German). Modern Standard German is mostly based on Central German dialects.

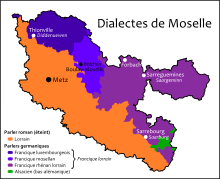

The Franconian, West Central German dialects are the Central Franconian dialects (Ripuarian and Moselle Franconian) and the Rhine Franconian dialects (Hessian and Palatine). These dialects are considered as

- German in Germany and Belgium

- Luxembourgish in Luxembourg

- Lorraine Franconian (spoken in Moselle) and as a Rhine Franconian variant of Alsatian (spoken in Alsace bossue only) in France

- Limburgish or Kerkrade dialect in the Netherlands.

Luxembourgish as well as the Transylvanian Saxon dialect spoken in Transylvania are based on Moselle Franconian dialects. The largest cities in the Franconian Central German area are Cologne and Frankfurt.

Further east, the non-Franconian, East Central German dialects are spoken (Thuringian, Upper Saxon, Ore Mountainian, and Lusatian-New Markish, and earlier, in the then German-speaking parts of Silesia also Silesian, and in then German southern East Prussia also High Prussian). The largest cities in the East Central German area are Berlin and Leipzig.

High Franconian

The High Franconian dialects are transitional dialects between Central and Upper German. They consist of the East and South Franconian dialects.

The East Franconian dialect branch is one of the most spoken dialect branches in Germany. These dialects are spoken in the region of Franconia and in the central parts of Saxon Vogtland. Franconia consists of the Bavarian districts of Upper, Middle, and Lower Franconia, the region of South Thuringia (Thuringia), and the eastern parts of the region of Heilbronn-Franken (Tauber Franconia and Hohenlohe) in Baden-Württemberg. The largest cities in the East Franconian area are Nuremberg and Würzburg.

South Franconian is mainly spoken in northern Baden-Württemberg in Germany, but also in the northeasternmost part of the region of Alsace in France. While these dialects are considered as dialects of German in Baden-Württemberg, they are considered as dialects of Alsatian in Alsace (most Alsatian dialects are Low Alemannic, however). The largest cities in the South Franconian area are Karlsruhe and Heilbronn.

Upper German

The Upper German dialects are the Alemannic dialects in the west and the Bavarian dialects in the east.

Alemannic

Alemannic dialects are spoken in Switzerland (High Alemannic in the densely populated Swiss Plateau, in the south also Highest Alemannic, and Low Alemannic in Basel), Baden-Württemberg (Swabian and Low Alemannic, in the southwest also High Alemannic), Bavarian Swabia (Swabian, in the southwesternmost part also Low Alemannic), Vorarlberg (Low, High, and Highest Alemannic), Alsace (Low Alemannic, in the southernmost part also High Alemannic), Liechtenstein (High and Highest Alemannic), and in the Tyrolean district of Reutte (Swabian). The Alemannic dialects are considered as Alsatian in Alsace. The largest cities in the Alemannic area are Stuttgart and Zürich.

Bavarian

Bavarian dialects are spoken in Austria (Vienna, Lower and Upper Austria, Styria, Carinthia, Salzburg, Burgenland, and in most parts of Tyrol), Bavaria (Upper and Lower Bavaria as well as Upper Palatinate), South Tyrol, southwesternmost Saxony (Southern Vogtlandian), and in the Swiss village of Samnaun. The largest cities in the Bavarian area are Vienna and Munich.

Grammar

German is a fusional language with a moderate degree of inflection, with three grammatical genders; as such, there can be a large number of words derived from the same root.

Noun inflection

German nouns inflect by case, gender, and number:

- four cases: nominative, accusative, genitive, and dative.

- three genders: masculine, feminine, and neuter. Word endings sometimes reveal grammatical gender: for instance, nouns ending in -ung (-ing), -schaft (-ship), -keit or heit (-hood, -ness) are feminine, nouns ending in -chen or -lein (diminutive forms) are neuter and nouns ending in -ismus (-ism) are masculine. Others are more variable, sometimes depending on the region in which the language is spoken. And some endings are not restricted to one gender: for example, -er (-er), such as Feier (feminine), celebration, party, Arbeiter (masculine), labourer, and Gewitter (neuter), thunderstorm.

- two numbers: singular and plural.

This degree of inflection is considerably less than in Old High German and other old Indo-European languages such as Latin, Ancient Greek, and Sanskrit, and it is also somewhat less than, for instance, Old English, modern Icelandic, or Russian. The three genders have collapsed in the plural. With four cases and three genders plus plural, there are 16 permutations of case and gender/number of the article (not the nouns), but there are only six forms of the definite article, which together cover all 16 permutations. In nouns, inflection for case is required in the singular for strong masculine and neuter nouns only in the genitive and in the dative (only in fixed or archaic expressions), and even this is losing ground to substitutes in informal speech.[69] The singular dative noun ending is considered archaic or at least old-fashioned in almost all contexts and is almost always dropped in writing, except in poetry, songs, proverbs, and other petrified forms. Weak masculine nouns share a common case ending for genitive, dative, and accusative in the singular. Feminine nouns are not declined in the singular. The plural has an inflection for the dative. In total, seven inflectional endings (not counting plural markers) exist in German: -s, -es, -n, -ns, -en, -ens, -e.

In German orthography, nouns and most words with the syntactical function of nouns are capitalised to make it easier for readers to determine the function of a word within a sentence (Am Freitag ging ich einkaufen. – "On Friday I went shopping."; Eines Tages kreuzte er endlich auf. – "One day he finally showed up.") This convention is almost unique to German today (shared perhaps only by the closely related Luxembourgish language and several insular dialects of the North Frisian language), but it was historically common in other languages such as Danish (which abolished the capitalization of nouns in 1948) and English.

Like the other Germanic languages, German forms noun compounds in which the first noun modifies the category given by the second: Hundehütte ("dog hut"; specifically: "dog kennel"). Unlike English, whose newer compounds or combinations of longer nouns are often written "open" with separating spaces, German (like some other Germanic languages) nearly always uses the "closed" form without spaces, for example: Baumhaus ("tree house"). Like English, German allows arbitrarily long compounds in theory (see also English compounds). The longest German word verified to be actually in (albeit very limited) use is Rindfleischetikettierungsüberwachungsaufgabenübertragungsgesetz, which, literally translated, is "beef labelling supervision duties assignment law" [from Rind (cattle), Fleisch (meat), Etikettierung(s) (labelling), Überwachung(s) (supervision), Aufgaben (duties), Übertragung(s) (assignment), Gesetz (law)]. However, examples like this are perceived by native speakers as excessively bureaucratic, stylistically awkward, or even satirical.

Verb inflection

The inflection of standard German verbs includes:

- two main conjugation classes: weak and strong (as in English). Additionally, there is a third class, known as mixed verbs, whose conjugation combines features of both the strong and weak patterns.

- three persons: first, second and third.

- two numbers: singular and plural.

- three moods: indicative, imperative and subjunctive (in addition to infinitive).

- two voices: active and passive. The passive voice uses auxiliary verbs and is divisible into static and dynamic. Static forms show a constant state and use the verb ’'to be'’ (sein). Dynamic forms show an action and use the verb "to become'’ (werden).

- two tenses without auxiliary verbs (present and preterite) and four tenses constructed with auxiliary verbs (perfect, pluperfect, future and future perfect).

- the distinction between grammatical aspects is rendered by combined use of the subjunctive and/or preterite marking so the plain indicative voice uses neither of those two markers; the subjunctive by itself often conveys reported speech; subjunctive plus preterite marks the conditional state; and the preterite alone shows either plain indicative (in the past), or functions as a (literal) alternative for either reported speech or the conditional state of the verb, when necessary for clarity.

- the distinction between perfect and progressive aspect is and has, at every stage of development, been a productive category of the older language and in nearly all documented dialects, but strangely enough it is now rigorously excluded from written usage in its present normalised form.

- disambiguation of completed vs. uncompleted forms is widely observed and regularly generated by common prefixes (blicken [to look], erblicken [to see – unrelated form: sehen]).

Verb prefixes

The meaning of basic verbs can be expanded and sometimes radically changed through the use of a number of prefixes. Some prefixes have a specific meaning; the prefix zer- refers to destruction, as in zerreißen (to tear apart), zerbrechen (to break apart), zerschneiden (to cut apart). Other prefixes have only the vaguest meaning in themselves; ver- is found in a number of verbs with a large variety of meanings, as in versuchen (to try) from suchen (to seek), vernehmen (to interrogate) from nehmen (to take), verteilen (to distribute) from teilen (to share), verstehen (to understand) from stehen (to stand).

Other examples include the following: haften (to stick), verhaften (to detain); kaufen (to buy), verkaufen (to sell); hören (to hear), aufhören (to cease); fahren (to drive), erfahren (to experience).

Many German verbs have a separable prefix, often with an adverbial function. In finite verb forms, it is split off and moved to the end of the clause and is hence considered by some to be a "resultative particle". For example, mitgehen, meaning "to go along", would be split, giving Gehen Sie mit? (Literal: "Go you with?"; Idiomatic: "Are you going along?").

Indeed, several parenthetical clauses may occur between the prefix of a finite verb and its complement (ankommen = to arrive, er kam an = he arrived, er ist angekommen = he has arrived):

- Er kam am Freitagabend nach einem harten Arbeitstag und dem üblichen Ärger, der ihn schon seit Jahren immer wieder an seinem Arbeitsplatz plagt, mit fraglicher Freude auf ein Mahl, das seine Frau ihm, wie er hoffte, bereits aufgetischt hatte, endlich zu Hause an.

A selectively literal translation of this example to illustrate the point might look like this:

- He "came" on Friday evening, after a hard day at work and the usual annoyances that had time and again been troubling him for years now at his workplace, with questionable joy, to a meal which, as he hoped, his wife had already put on the table, finally home "to".

Word order

German word order is generally with the V2 word order restriction and also with the SOV word order restriction for main clauses. For polar questions, exclamations, and wishes, the finite verb always has the first position. In subordinate clauses, the verb occurs at the very end.

German requires a verbal element (main verb or auxiliary verb) to appear second in the sentence. The verb is preceded by the topic of the sentence. The element in focus appears at the end of the sentence. For a sentence without an auxiliary, these are several possibilities:

- Der alte Mann gab mir gestern das Buch. (The old man gave me yesterday the book; normal order)

- Das Buch gab mir gestern der alte Mann. (The book gave [to] me yesterday the old man)

- Das Buch gab der alte Mann mir gestern. (The book gave the old man [to] me yesterday)

- Das Buch gab mir der alte Mann gestern. (The book gave [to] me the old man yesterday)

- Gestern gab mir der alte Mann das Buch. (Yesterday gave [to] me the old man the book, normal order)

- Mir gab der alte Mann das Buch gestern. ([To] me gave the old man the book yesterday (entailing: as for someone else, it was another date))

The position of a noun in a German sentence has no bearing on its being a subject, an object or another argument. In a declarative sentence in English, if the subject does not occur before the predicate, the sentence could well be misunderstood.

However, German's flexible word order allows one to emphasise specific words:

Normal word order:

- Der Direktor betrat gestern um 10 Uhr mit einem Schirm in der Hand sein Büro.

- The manager entered yesterday at 10 o'clock with an umbrella in the hand his office.

Object in front:

- Sein Büro betrat der Direktor gestern um 10 Uhr mit einem Schirm in der Hand.

- His office entered the manager yesterday at 10 o'clock with an umbrella in the hand.

- The object Sein Büro (his office) is thus highlighted; it could be the topic of the next sentence.

Adverb of time in front:

- Gestern betrat der Direktor um 10 Uhr mit einem Schirm in der Hand sein Büro. (aber heute ohne Schirm)

- Yesterday entered the manager at 10 o'clock with an umbrella in the hand his office. (but today without umbrella)

Both time expressions in front:

- Gestern um 10 Uhr betrat der Direktor mit einem Schirm in der Hand sein Büro.

- Yesterday at 10 o'clock entered the manager with an umbrella in the hand his office.

- The full-time specification Gestern um 10 Uhr is highlighted.

Another possibility:

- Gestern um 10 Uhr betrat der Direktor sein Büro mit einem Schirm in der Hand.

- Yesterday at 10 o'clock the manager entered his office with an umbrella in the hand.

- Both the time specification and the fact he carried an umbrella are accentuated.

Swapped adverbs:

- Der Direktor betrat mit einem Schirm in der Hand gestern um 10 Uhr sein Büro.

- The manager entered with an umbrella in the hand yesterday at 10 o'clock his office.

- The phrase mit einem Schirm in der Hand is highlighted.

Swapped object:

- Der Direktor betrat gestern um 10 Uhr sein Büro mit einem Schirm in der Hand.

- The manager entered yesterday at 10 o'clock his office with an umbrella in the hand.

- The time specification and the object sein Büro (his office) are lightly accentuated.

The flexible word order also allows one to use language "tools" (such as poetic meter and figures of speech) more freely.

Auxiliary verbs

When an auxiliary verb is present, it appears in second position, and the main verb appears at the end. This occurs notably in the creation of the perfect tense. Many word orders are still possible:

- Der alte Mann hat mir heute das Buch gegeben. (The old man has me today the book given.)

- Das Buch hat der alte Mann mir heute gegeben. (The book has the old man me today given.)

- Heute hat der alte Mann mir das Buch gegeben. (Today has the old man me the book given.)

The main verb may appear in first position to put stress on the action itself. The auxiliary verb is still in second position.

- Gegeben hat mir der alte Mann das Buch heute. (Given has me the old man the book today.) The bare fact that the book has been given is emphasized, as well as 'today'.

Modal verbs

Sentences using modal verbs place the infinitive at the end. For example, the English sentence "Should he go home?" would be rearranged in German to say "Should he (to) home go?" (Soll er nach Hause gehen?). Thus, in sentences with several subordinate or relative clauses, the infinitives are clustered at the end. Compare the similar clustering of prepositions in the following (highly contrived) English sentence: "What did you bring that book that I do not like to be read to out of up for?"

Multiple infinitives

German subordinate clauses have all verbs clustered at the end. Given that auxiliaries encode future, passive, modality, and the perfect, very long chains of verbs at the end of the sentence can occur. In these constructions, the past participle formed with ge- is often replaced by the infinitive.

- Man nimmt an, dass der Deserteur wohl erschossenV wordenpsv seinperf sollmod

- One suspects that the deserter probably shot become be should.

- ("It is suspected that the deserter probably had been shot")

- Er wusste nicht, dass der Agent einen Nachschlüssel hatte machen lassen

- He knew not that the agent a picklock had make let

- Er wusste nicht, dass der Agent einen Nachschlüssel machen lassen hatte

- He knew not that the agent a picklock make let had

- ("He did not know that the agent had had a picklock made")

The order at the end of such strings is subject to variation, but the second one in the last example is unusual.

Vocabulary

Most German vocabulary is derived from the Germanic branch of the Indo-European language family.[70] However, there is a significant amount of loanwords from other languages, in particular Latin, Greek, Italian, French, and most recently English.[71] In the early 19th century, Joachim Heinrich Campe estimated that one fifth of the total German vocabulary was of French or Latin origin.[72]

Latin words were already imported into the predecessor of the German language during the Roman Empire and underwent all the characteristic phonetic changes in German. Their origin is thus no longer recognizable for most speakers (e.g. Pforte, Tafel, Mauer, Käse, Köln from Latin porta, tabula, murus, caseus, Colonia). Borrowing from Latin continued after the fall of the Roman Empire during Christianization, mediated by the church and monasteries. Another important influx of Latin words can be observed during Renaissance humanism. In a scholarly context, the borrowings from Latin have continued until today, in the last few decades often indirectly through borrowings from English. During the 15th to 17th centuries, the influence of Italian was great, leading to many Italian loanwords in the fields of architecture, finance, and music. The influence of the French language in the 17th to 19th centuries resulted in an even greater import of French words. The English influence was already present in the 19th century, but it did not become dominant until the second half of the 20th century.

Thus, Notker Labeo was able to translate Aristotelian treatises into pure (Old High) German in the decades after the year 1000.[73] The tradition of loan translation was revitalized in the 18th century with linguists like Joachim Heinrich Campe, who introduced close to 300 words that are still used in modern German. Even today, there are movements that try to promote the Ersatz (substitution) of foreign words that are deemed unnecessary with German alternatives.[74] It is claimed that this would also help in spreading modern or scientific notions among the less educated and as well democratise public life.

As in English, there are many pairs of synonyms due to the enrichment of the Germanic vocabulary with loanwords from Latin and Latinized Greek. These words often have different connotations from their Germanic counterparts and are usually perceived as more scholarly.

- Historie, historisch – "history, historical", (Geschichte, geschichtlich)

- Humanität, human – "humaneness, humane", (Menschlichkeit, menschlich)[note 5]

- Millennium – "millennium", (Jahrtausend)

- Perzeption – "perception", (Wahrnehmung)

- Vokabular – "vocabulary", (Wortschatz)

The size of the vocabulary of German is difficult to estimate. The Deutsches Wörterbuch (German Dictionary) initiated by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm already contained over 330,000 headwords in its first edition. The modern German scientific vocabulary is estimated at nine million words and word groups (based on the analysis of 35 million sentences of a corpus in Leipzig, which as of July 2003 included 500 million words in total).[75]

The Duden is the de facto official dictionary of the German language, first published by Konrad Duden in 1880. The Duden is updated regularly, with new editions appearing every four or five years. As of August 2017, it was in its 27th edition and in 12 volumes, each covering different aspects such as loanwords, etymology, pronunciation, synonyms, and so forth.

The first of these volumes, Die deutsche Rechtschreibung (German Orthography), has long been the prescriptive source for the spelling of German. The Duden has become the bible of the German language, being the definitive set of rules regarding grammar, spelling and usage of German.[76]

The Österreichisches Wörterbuch ("Austrian Dictionary"), abbreviated ÖWB, is the official dictionary of the German language in the Republic of Austria. It is edited by a group of linguists under the authority of the Austrian Federal Ministry of Education, Arts and Culture (German: Bundesministerium für Unterricht, Kunst und Kultur). It is the Austrian counterpart to the German Duden and contains a number of terms unique to Austrian German or more frequently used or differently pronounced there.[77] A considerable amount of this "Austrian" vocabulary is also common in Southern Germany, especially Bavaria, and some of it is used in Switzerland as well. Since the 39th edition in 2001 the orthography of the ÖWB has been adjusted to the German spelling reform of 1996. The dictionary is also officially used in the Italian province of South Tyrol.

English to German cognates

This is a selection of cognates in both English and German. Instead of the usual infinitive ending -en, German verbs are indicated by a hyphen after their stems. Words that are written with capital letters in German are nouns.

| English | German | English | German | English | German | English | German | English | German | English | German | English | German | English | German | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| and | und | arm | Arm | bear | Bär | beaver | Biber | bee | Biene | beer | Bier | best | best | better | besser | |||||||

| blink | blink- | bloom | blüh- | blue | blau | boat | Boot | book | Buch | brew | brau- | brewery | Brauerei | bridge | Brücke | |||||||

| brow | Braue | brown | braun | church | Kirche | cold | kalt | cool | kühl | dale | Tal | dam | Damm | dance | tanz- | |||||||

| dough | Teig | dream | Traum | dream | träum- | drink | Getränk | drink | trink- | ear | Ohr | earth | Erde | eat | ess- | |||||||

| far | fern | feather | Feder | fern | Farn | field | Feld | finger | Finger | fish | Fisch | fisher | Fischer | flee | flieh- | |||||||

| flight | Flug | flood | Flut | flow | fließ- | flow | Fluss | fly | Fliege | fly | flieg- | for | für | ford | Furt | |||||||

| four | vier | fox | Fuchs | glass | Glas | go | geh- | gold | Gold | good | gut | grass | Gras | grasshopper | Grashüpfer | |||||||

| green | grün | grey | grau | hag | Hexe | hail | Hagel | hand | Hand | hat | Hut | hate | Hass | haven | Hafen | |||||||

| hay | Heu | hear | hör- | heart | Herz | heat | Hitze | heath | Heide | high | hoch | honey | Honig | hornet | Hornisse | |||||||

| hundred | hundert | hunger | Hunger | hut | Hütte | ice | Eis | king | König | kiss | Kuss | kiss | küss- | knee | Knie | |||||||

| land | Land | landing | Landung | laugh | lach- | lie, lay | lieg-, lag | lie, lied | lüg-, log | light (A) | leicht | light | Licht | live | leb- | |||||||

| liver | Leber | love | Liebe | man | Mann | middle | Mitte | midnight | Mitternacht | moon | Mond | moss | Moos | mouth | Mund | |||||||

| mouth (river) | Mündung | night | Nacht | nose | Nase | nut | Nuss | over | über | plant | Pflanze | quack | quak- | rain | Regen | |||||||

| rainbow | Regenbogen | red | rot | ring | Ring | sand | Sand | say | sag- | sea | See (f) | seam | Saum | seat | Sitz | |||||||

| see | seh- | sheep | Schaf | shimmer | schimmer- | shine | schein- | ship | Schiff | silver | Silber | sing | sing- | sit | sitz- | |||||||

| snow | Schnee | soul | Seele | speak | sprech- | spring | spring- | star | Stern | stitch | Stich | stork | Storch | storm | Sturm | |||||||

| stormy | stürmisch | strand | strand- | straw | Stroh | straw bale | Strohballen | stream | Strom | stream | ström- | stutter | stotter- | summer | Sommer | |||||||

| sun | Sonne | sunny | sonnig | swan | Schwan | tell | erzähl- | that (C) | dass | the | der, die, das, den, dem | then | dann | thirst | Durst | |||||||

| thistle | Distel | thorn | Dorn | thousand | tausend | thunder | Donner | zwitscher- | upper | ober | warm | warm | wasp | Wespe | ||||||||

| water | Wasser | weather | Wetter | weave | web- | well | Quelle | well | wohl | which | welch | white | weiß | wild | wild | |||||||

| wind | Wind | winter | Winter | wolf | Wolf | word | Wort | world | Welt | yarn | Garn | year | Jahr | yellow | gelb | |||||||

| English | German | English | German | English | German | English | German | English | German | English | German | English | German | English | German |

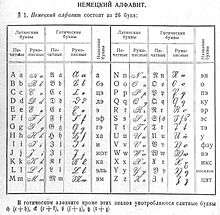

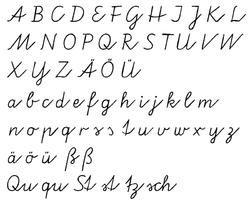

Orthography

German is written in the Latin alphabet. In addition to the 26 standard letters, German has three vowels with an umlaut mark, namely ä, ö and ü, as well as the eszett or scharfes s (sharp s): ß. In Switzerland and Liechtenstein, ss is used instead of ß. Since ß can never occur at the beginning of a word, it has no traditional uppercase form.

Written texts in German are easily recognisable as such by distinguishing features such as umlauts and certain orthographical features – German is the only major language that capitalizes all nouns, a relic of a widespread practice in Northern Europe in the early modern era (including English for a while, in the 1700s) – and the frequent occurrence of long compounds. Because legibility and convenience set certain boundaries, compounds consisting of more than three or four nouns are almost exclusively found in humorous contexts. (In contrast, although English can also string nouns together, it usually separates the nouns with spaces. For example, "toilet bowl cleaner".)

Present

Before the German orthography reform of 1996, ß replaced ss after long vowels and diphthongs and before consonants, word-, or partial-word endings. In reformed spelling, ß replaces ss only after long vowels and diphthongs.

Since there is no traditional capital form of ß, it was replaced by SS when capitalization was required. For example, Maßband (tape measure) became MASSBAND in capitals. An exception was the use of ß in legal documents and forms when capitalizing names. To avoid confusion with similar names, lower case ß was maintained (thus "KREßLEIN" instead of "KRESSLEIN"). Capital ß (ẞ) was ultimately adopted into German orthography in 2017, ending a long orthographic debate (thus "KREẞLEIN and KRESSLEIN").[78]

Umlaut vowels (ä, ö, ü) are commonly transcribed with ae, oe, and ue if the umlauts are not available on the keyboard or other medium used. In the same manner ß can be transcribed as ss. Some operating systems use key sequences to extend the set of possible characters to include, amongst other things, umlauts; in Microsoft Windows this is done using Alt codes. German readers understand these transcriptions (although they appear unusual), but they are avoided if the regular umlauts are available, because they are a makeshift and not proper spelling. (In Westphalia and Schleswig-Holstein, city and family names exist where the extra e has a vowel lengthening effect, e.g. Raesfeld [ˈraːsfɛlt], Coesfeld [ˈkoːsfɛlt] and Itzehoe [ɪtsəˈhoː], but this use of the letter e after a/o/u does not occur in the present-day spelling of words other than proper nouns.)

There is no general agreement on where letters with umlauts occur in the sorting sequence. Telephone directories treat them by replacing them with the base vowel followed by an e. Some dictionaries sort each umlauted vowel as a separate letter after the base vowel, but more commonly words with umlauts are ordered immediately after the same word without umlauts. As an example in a telephone book Ärzte occurs after Adressenverlage but before Anlagenbauer (because Ä is replaced by Ae). In a dictionary Ärzte comes after Arzt, but in some dictionaries Ärzte and all other words starting with Ä may occur after all words starting with A. In some older dictionaries or indexes, initial Sch and St are treated as separate letters and are listed as separate entries after S, but they are usually treated as S+C+H and S+T.

Written German also typically uses an alternative opening inverted comma (quotation mark) as in "Guten Morgen!".

Past

Until the early 20th century, German was mostly printed in blackletter typefaces (mostly in Fraktur, but also in Schwabacher) and written in corresponding handwriting (for example Kurrent and Sütterlin). These variants of the Latin alphabet are very different from the serif or sans-serif Antiqua typefaces used today, and the handwritten forms in particular are difficult for the untrained to read. The printed forms, however, were claimed by some to be more readable when used for Germanic languages.[79] (Often, foreign names in a text were printed in an Antiqua typeface even though the rest of the text was in Fraktur.) The Nazis initially promoted Fraktur and Schwabacher because they were considered Aryan, but they abolished them in 1941, claiming that these letters were Jewish.[80] It is also believed that the Nazi régime had banned this script as they realized that Fraktur would inhibit communication in the territories occupied during World War II.[81]

The Fraktur script however remains present in everyday life in pub signs, beer brands and other forms of advertisement, where it is used to convey a certain rusticality and antiquity.

A proper use of the long s (langes s), ſ, is essential for writing German text in Fraktur typefaces. Many Antiqua typefaces also include the long s. A specific set of rules applies for the use of long s in German text, but nowadays it is rarely used in Antiqua typesetting. Any lower case "s" at the beginning of a syllable would be a long s, as opposed to a terminal s or short s (the more common variation of the letter s), which marks the end of a syllable; for example, in differentiating between the words Wachſtube (guard-house) and Wachstube (tube of polish/wax). One can easily decide which "s" to use by appropriate hyphenation, (Wach-ſtube vs. Wachs-tube). The long s only appears in lower case.

Reform of 1996

The orthography reform of 1996 led to public controversy and considerable dispute. The states (Bundesländer) of North Rhine-Westphalia and Bavaria refused to accept it. At one point, the dispute reached the highest court, which quickly dismissed it, claiming that the states had to decide for themselves and that only in schools could the reform be made the official rule – everybody else could continue writing as they had learned it. After 10 years, without any intervention by the federal parliament, a major revision was installed in 2006, just in time for the coming school year. In 2007, some traditional spellings were finally invalidated; however, in 2008, many of the old comma rules were again put in force.

The most noticeable change was probably in the use of the letter ß, called scharfes s (Sharp S) or ess-zett (pronounced ess-tsett). Traditionally, this letter was used in three situations:

- After a long vowel or vowel combination;

- Before a t;

- At the end of a syllable.

Examples are Füße, paßt, and daß. Currently, only the first rule is in effect, making the correct spellings Füße, passt, and dass. The word Fuß 'foot' has the letter ß because it contains a long vowel, even though that letter occurs at the end of a syllable. The logic of this change is that an 'ß' is a single letter whereas 'ss' are two letters, so the same distinction applies as (for example) between the words den and denn.

Phonology

Vowels

In German, vowels (excluding diphthongs; see below) are either short or long, as follows:

| A | Ä | E | I | O | Ö | U | Ü | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short | /a/ | /ɛ/ | /ɛ/, /ə/ | /ɪ/ | /ɔ/ | /œ/ | /ʊ/ | /ʏ/ |

| Long | /aː/ | /ɛː/, /eː/ | /eː/ | /iː/ | /oː/ | /øː/ | /uː/ | /yː/ |

Short /ɛ/ is realized as [ɛ] in stressed syllables (including secondary stress), but as [ə] in unstressed syllables. Note that stressed short /ɛ/ can be spelled either with e or with ä (for instance, hätte 'would have' and Kette 'chain' rhyme). In general, the short vowels are open and the long vowels are close. The one exception is the open /ɛː/ sound of long Ä; in some varieties of standard German, /ɛː/ and /eː/ have merged into [eː], removing this anomaly. In that case, pairs like Bären/Beeren 'bears/berries' or Ähre/Ehre 'spike (of wheat)/honour' become homophonous (see: Captain Bluebear).

In many varieties of standard German, an unstressed /ɛr/ is not pronounced [ər] but vocalised to [ɐ].

Whether any particular vowel letter represents the long or short phoneme is not completely predictable, although the following regularities exist:

- If a vowel (other than i) is at the end of a syllable or followed by a single consonant, it is usually pronounced long (e.g. Hof [hoːf]).

- If a vowel is followed by h or if an i is followed by an e, it is long.

- If the vowel is followed by a double consonant (e.g. ff, ss or tt), ck, tz or a consonant cluster (e.g. st or nd), it is nearly always short (e.g. hoffen [ˈhɔfən]). Double consonants are used only for this function of marking preceding vowels as short; the consonant itself is never pronounced lengthened or doubled, in other words this is not a feeding order of gemination and then vowel shortening.

Both of these rules have exceptions (e.g. hat [hat] "has" is short despite the first rule; Mond [moːnt] "moon" is long despite the second rule). For an i that is neither in the combination ie (making it long) nor followed by a double consonant or cluster (making it short), there is no general rule. In some cases, there are regional differences. In central Germany (Hesse), the o in the proper name "Hoffmann" is pronounced long, whereas most other Germans would pronounce it short. The same applies to the e in the geographical name "Mecklenburg" for people in that region. The word Städte "cities" is pronounced with a short vowel [ˈʃtɛtə] by some (Jan Hofer, ARD Television) and with a long vowel [ˈʃtɛːtə] by others (Marietta Slomka, ZDF Television). Finally, a vowel followed by ch can be short (Fach [fax] "compartment", Küche [ˈkʏçə] "kitchen") or long (Suche [ˈzuːxə] "search", Bücher [ˈbyːçɐ] "books") almost at random. Thus, Lache is homographous between [laːxə] Lache "puddle" and [laxə] Lache "manner of laughing" (colloquial) or lache! "laugh!" (imperative).

German vowels can form the following digraphs (in writing) and diphthongs (in pronunciation); note that the pronunciation of some of them (ei, äu, eu) is very different from what one would expect when considering the component letters:

| Spelling | ai, ei, ay, ey | au | äu, eu |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /aɪ̯/ | /aʊ̯/ | /ɔʏ̯/ |

Additionally, the digraph ie generally represents the phoneme /iː/, which is not a diphthong. In many varieties, an /r/ at the end of a syllable is vocalised. However, a sequence of a vowel followed by such a vocalised /r/ is not a phonemic diphthong: Bär [bɛːɐ̯] "bear", er [eːɐ̯] "he", wir [viːɐ̯] "we", Tor [toːɐ̯] "gate", kurz [kʊɐ̯ts] "short", Wörter [vœɐ̯tɐ] "words".

In most varieties of standard German, syllables that begin with a vowel are preceded by a glottal stop [ʔ].

Consonants

With approximately 26 phonemes, the German consonant system exhibits an average number of consonants in comparison with other languages. One of the more noteworthy ones is the unusual affricate /p͡f/. The consonant inventory of the standard language is shown below.

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||

| Plosive | p3 b | t3 d | k3 ɡ | |||

| Affricate | pf | ts | tʃ (dʒ)4 | |||

| Fricative | f v | s z | ʃ (ʒ)4 | x1 | (ʁ)2 | h |

| Trill | r2 | (ʀ)2 | ||||

| Approximant | l | j |

- 1/x/ has two allophones, [x] and [ç], after back and front vowels, respectively.

- 2/r/ has three allophones in free variation: [r], [ʁ] and [ʀ]. In the syllable coda, the allophone [ɐ] is found in many varieties.

- 3 The voiceless stops /p/, /t/, /k/ are aspirated except when preceded by a sibilant, identical to English usage.

- 4/d͡ʒ/ and /ʒ/ occur only in words of foreign (usually English or French) origin.

- Where a stressed syllable has an initial vowel, it is preceded by [ʔ]. As its presence is predictable from context, [ʔ] is not considered a phoneme.

Consonant spellings

- c standing by itself is not a German letter. In borrowed words, it is usually pronounced [t͡s] (before ä, äu, e, i, ö, ü, y) or [k] (before a, o, u, and consonants). The combination ck is, as in English, used to indicate that the preceding vowel is short.

- ch occurs often and is pronounced either [ç] (after ä, ai, äu, e, ei, eu, i, ö, ü and consonants; in the diminutive suffix -chen; and at the beginning of a word), [x] (after a, au, o, u), or [k] at the beginning of a word before a, o, u and consonants. Ch never occurs at the beginning of an originally German word. In borrowed words with initial Ch before front vowels (Chemie "chemistry" etc.), [ç] is considered standard. However, Upper Germans and Franconians (in the geographical sense) replace it with [k], as German as a whole does before darker vowels and consonants such as in Charakter, Christentum. Middle Germans (except Franconians) will borrow a [ʃ] from the French model. Both consider the other's variant, and Upper Germans also the standard [ç], to be particularly awkward and unusual.

- dsch is pronounced [d͡ʒ] (e.g. Dschungel /ˈd͡ʒʊŋəl/ "jungle") but appears in a few loanwords only.

- f is pronounced [f] as in "father".

- h is pronounced [h] as in "home" at the beginning of a syllable. After a vowel it is silent and only lengthens the vowel (e.g. Reh [ʁeː] = roe deer).

- j is pronounced [j] in Germanic words (Jahr [jaːɐ̯]) like "y" in "year". In recent loanwords, it follows more or less the respective languages' pronunciations.

- l is always pronounced [l], never *[ɫ] (the English "dark L").

- q only exists in combination with u and is pronounced [kv]. It appears in both Germanic and Latin words (quer [kveːɐ̯]; Qualität [kvaliˈtɛːt]). But as most words containing q are Latinate, the letter is considerably rarer in German than it is in English.

- r is usually pronounced in a guttural fashion (a voiced uvular fricative [ʁ] or uvular trill [ʀ]) in front of a vowel or consonant (Rasen [ˈʁaːzən]; Burg [bʊʁk]). In spoken German, however, it is commonly vocalised after a vowel (er being pronounced rather like [ˈɛɐ̯] – Burg [bʊɐ̯k]). In some varieties, the r is pronounced as a "tongue-tip" r (the alveolar trill [r]).