Etymology

Etymology (/ˌɛtɪˈmɒlədʒi/)[1] is the study of the history of words.[1] By extension, the phrase "the etymology of [a word]" means the origin of a particular word. For place names, there is a specific term, toponymy.

| Part of a series on |

| Linguistics |

|---|

|

|

For languages with a long written history, etymologists make use of texts, and texts about the language, to gather knowledge about how words were used during earlier periods, how they developed in meaning and form, or when and how they entered the language. Etymologists also apply the methods of comparative linguistics to reconstruct information about forms that are too old for any direct information to be available.

By analyzing related languages with a technique known as the comparative method, linguists can make inferences about their shared parent language and its vocabulary. In this way, word roots in European languages, for example, can be traced all the way back to the origin of the Indo-European language family.

Even though etymological research originally grew from the philological tradition, much current etymological research is done on language families where little or no early documentation is available, such as Uralic and Austronesian.

The word etymology derives from the Greek word ἐτυμολογία (etumología), itself from ἔτυμον (étumon), meaning "true sense or sense of a truth", and the suffix -logia, denoting "the study of".[2][3]

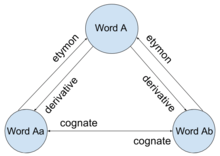

The term etymon refers to a word or morpheme (e.g., stem[4] or root[5]) from which a later word or morpheme derives. For example, the Latin word candidus, which means "white", is the etymon of English candid. Relationships are often less transparent, however. English place names such as Winchester, Gloucester, Tadcaster share in different modern forms a suffixed etymon that was once meaningful, Latin castrum 'fort'.

Methods

Etymologists apply a number of methods to study the origins of words, some of which are:

- Philological research. Changes in the form and meaning of the word can be traced with the aid of older texts, if such are available.

- Making use of dialectological data. The form or meaning of the word might show variations between dialects, which may yield clues about its earlier history.

- The comparative method. By a systematic comparison of related languages, etymologists may often be able to detect which words derive from their common ancestor language and which were instead later borrowed from another language.

- The study of semantic change. Etymologists must often make hypotheses about changes in the meaning of particular words. Such hypotheses are tested against the general knowledge of semantic shifts. For example, the assumption of a particular change of meaning may be substantiated by showing that the same type of change has occurred in other languages as well.

Types of word origins

Etymological theory recognizes that words originate through a limited number of basic mechanisms, the most important of which are language change, borrowing (i.e., the adoption of "loanwords" from other languages); word formation such as derivation and compounding; and onomatopoeia and sound symbolism (i.e., the creation of imitative words such as "click" or "grunt").

While the origin of newly emerged words is often more or less transparent, it tends to become obscured through time due to sound change or semantic change. Due to sound change, it is not readily obvious that the English word set is related to the word sit (the former is originally a causative formation of the latter). It is even less obvious that bless is related to blood (the former was originally a derivative with the meaning "to mark with blood").

Semantic change may also occur. For example, the English word bead originally meant "prayer". It acquired its modern meaning through the practice of counting the recitation of prayers by using beads.

English language

English derives from Old English (sometimes referred to as Anglo-Saxon), a West Germanic variety, although its current vocabulary includes words from many languages.[6] The Old English roots may be seen in the similarity of numbers in English and German, particularly seven/sieben, eight/acht, nine/neun, and ten/zehn. Pronouns are also cognate: I/mine/me and ich/mein/mich; thou/thine/thee and du/dein/dich; we/wir and us/uns; she/sie; your/ihr. However, language change has eroded many grammatical elements, such as the noun case system, which is greatly simplified in modern English. Certain elements of vocabulary are borrowed from French and other Romance languages, but most of the common words used in English are of Germanic origin.

When the Normans conquered England in 1066 (see Norman Conquest), they brought their Norman language with them. During the Anglo-Norman period, which united insular and continental territories, the ruling class spoke Anglo-Norman, while the peasants spoke the vernacular English of the time. Anglo-Norman was the conduit for the introduction of French into England, aided by the circulation of Langue d'oïl literature from France.

This led to many paired words of French and English origin. For example, beef is related, through borrowing, to modern French bœuf, veal to veau, pork to porc, and poultry to poulet. All these words, French and English, refer to the meat rather than to the animal. Words that refer to farm animals, on the other hand, tend to be cognates of words in other Germanic languages. For example, swine/Schwein, cow/Kuh, calf/Kalb, and sheep/Schaf. The variant usage has been explained by the proposition that it was the Norman rulers who mostly ate meat (an expensive commodity) and the Anglo-Saxons who farmed the animals. This explanation has passed into common folklore but has been disputed.

Assimilation of foreign words

English has proved accommodating to words from many languages. Scientific terminology, for example, relies heavily on words of Latin and Greek origin, but there are a great many non-scientific examples. Spanish has contributed many words, particularly in the southwestern United States. Examples include buckaroo, alligator, rodeo, savvy, and states' names such as Colorado and Florida. Albino, palaver, lingo, verandah, and coconut from Portuguese; diva and prima donna from Italian. Modern French has contributed café, cinema, naive, nicotine and many more.

Smorgasbord, slalom, and ombudsman are from Swedish, Norwegian and Danish; sauna from Finnish; adobe, alcohol, algebra, algorithm, apricot, assassin, caliber, cotton, hazard, jacket, jar, julep, mosque, Muslim, orange, safari, sofa, and zero from Arabic (often via other languages); behemoth, hallelujah, Satan, jubilee, and rabbi from Hebrew; taiga, steppe, Bolshevik, and sputnik from Russian.

Bandanna, bungalow, dungarees, guru, karma, and pundit come from Urdu, Hindi and ultimately Sanskrit; curry from Tamil; honcho, sushi, and tsunami from Japanese; dim sum, gung ho, kowtow, kumquat and typhoon from Cantonese. Kampong and amok are from Malay; and boondocks from the Tagalog word for hills or mountains, bundok. Ketchup derives from one or more South-East Asia and East Indies words for fish sauce or soy sauce, likely by way of Chinese, though the precise path is unclear: Malay kicap, Indonesian kecap, Chinese Min Nan kê-chiap and cognates in other Chinese dialects.

Surprisingly few loanwords, however, come from other languages native to the British Isles. Those that exist include coracle, cromlech and (probably) flannel, gull and penguin from Welsh; galore and whisky from Scottish Gaelic; phoney, trousers, and Tory from Irish; and eerie and canny from Scots (or related Northern English dialects).

Many Canadian English and American English words (especially but not exclusively plant and animal names) are loanwords from Indigenous American languages, such as barbecue, bayou, chili, chipmunk, hooch, hurricane, husky, mesquite, opossum, pecan, squash, toboggan, and tomato.

History

The search for meaningful origins for familiar or strange words is far older than the modern understanding of linguistic evolution and the relationships of languages, which began no earlier than the 18th century. From Antiquity through the 17th century, from Pāṇini to Pindar to Sir Thomas Browne, etymology had been a form of witty wordplay, in which the supposed origins of words were creatively imagined to satisfy contemporary requirements; for example, the Greek poet Pindar (born in approximately 522 BCE) employed inventive etymologies to flatter his patrons. Plutarch employed etymologies insecurely based on fancied resemblances in sounds. Isidore of Seville's Etymologiae was an encyclopedic tracing of "first things" that remained uncritically in use in Europe until the sixteenth century. Etymologicum genuinum is a grammatical encyclopedia edited at Constantinople in the ninth century, one of several similar Byzantine works. The thirteenth-century Legenda Aurea, as written by Jacobus de Vorgagine, begins each vita of a saint with a fanciful excursus in the form of an etymology.[7]

Ancient Sanskrit

The Sanskrit linguists and grammarians of ancient India were the first to make a comprehensive analysis of linguistics and etymology. The study of Sanskrit etymology has provided Western scholars with the basis of historical linguistics and modern etymology. Four of the most famous Sanskrit linguists are:

- Yaska (c. 6th–5th centuries BCE)

- Pāṇini (c. 520–460 BCE)

- Kātyāyana (2nd century BCE)

- Patañjali (2nd century BCE)

These linguists were not the earliest Sanskrit grammarians, however. They followed a line of ancient grammarians of Sanskrit who lived several centuries earlier like Sakatayana of whom very little is known. The earliest of attested etymologies can be found in Vedic literature in the philosophical explanations of the Brahmanas, Aranyakas, and Upanishads.

The analyses of Sanskrit grammar done by the previously mentioned linguists involved extensive studies on the etymology (called Nirukta or Vyutpatti in Sanskrit) of Sanskrit words, because the ancient Indo-Aryans considered sound and speech itself to be sacred and, for them, the words of the sacred Vedas contained deep encoding of the mysteries of the soul and God.

Ancient Greco-Roman

One of the earliest philosophical texts of the Classical Greek period to address etymology was the Socratic dialogue Cratylus (c. 360 BCE) by Plato. During much of the dialogue, Socrates makes guesses as to the origins of many words, including the names of the gods. In his Odes Pindar spins complimentary etymologies to flatter his patrons. Plutarch (Life of Numa Pompilius) spins an etymology for pontifex, while explicitly dismissing the obvious, and actual "bridge-builder":

the priests, called Pontifices.... have the name of Pontifices from potens, powerful, because they attend the service of the gods, who have power and command over all. Others make the word refer to exceptions of impossible cases; the priests were to perform all the duties possible to them; if anything lay beyond their power, the exception was not to be cavilled at. The most common opinion is the most absurd, which derives this word from pons, and assigns the priests the title of bridge-makers. The sacrifices performed on the bridge were amongst the most sacred and ancient, and the keeping and repairing of the bridge attached, like any other public sacred office, to the priesthood.

Medieval

Isidore of Seville compiled a volume of etymologies to illuminate the triumph of religion. Each saint's legend in Jacob de Voragine's Legenda Aurea begins with an etymological discourse on the saint's name:

Lucy is said of light, and light is beauty in beholding, after that S. Ambrose saith: The nature of light is such, she is gracious in beholding, she spreadeth over all without lying down, she passeth in going right without crooking by right long line; and it is without dilation of tarrying, and therefore it is showed the blessed Lucy hath beauty of virginity without any corruption; essence of charity without disordinate love; rightful going and devotion to God, without squaring out of the way; right long line by continual work without negligence of slothful tarrying. In Lucy is said, the way of light.[8]

Modern era

Etymology in the modern sense emerged in the late 18th-century European academia, within the context of the wider "Age of Enlightenment," although preceded by 17th century pioneers such as Marcus Zuerius van Boxhorn, Gerardus Vossius, Stephen Skinner, Elisha Coles, and William Wotton. The first known systematic attempt to prove the relationship between two languages on the basis of similarity of grammar and lexicon was made in 1770 by the Hungarian, János Sajnovics, when he attempted to demonstrate the relationship between Sami and Hungarian (work that was later extended to the whole Finno-Ugric language family in 1799 by his fellow countryman, Samuel Gyarmathi).[9]

The origin of modern historical linguistics is often traced to Sir William Jones, a Welsh philologist living in India, who in 1782 observed the genetic relationship between Sanskrit, Greek and Latin. Jones published his The Sanscrit Language in 1786, laying the foundation for the field of Indo-European linguistics.[10]

The study of etymology in Germanic philology was introduced by Rasmus Christian Rask in the early 19th century and elevated to a high standard with the German Dictionary of the Brothers Grimm. The successes of the comparative approach culminated in the Neogrammarian school of the late 19th century. Still in the 19th century, German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche used etymological strategies (principally and most famously in On the Genealogy of Morals, but also elsewhere) to argue that moral values have definite historical (specifically, cultural) origins where modulations in meaning regarding certain concepts (such as "good" and "evil") show how these ideas had changed over time—according to which value-system appropriated them. This strategy gained popularity in the 20th century, and philosophers, such as Jacques Derrida, have used etymologies to indicate former meanings of words to de-center the "violent hierarchies" of Western philosophy.

See also

- Bongo-Bongo

- Cognate

- Epeolatry

- Etymological dictionary

- Etymological fallacy

- False cognate

- False etymology

- Folk etymology

- Historical linguistics

- Lexicology

- Lists of etymologies

- Malapropism

- Medieval etymology

- Neologism

- Philology

- Phono-semantic matching

- Proto-language

- Pseudoscientific language comparison

- Semantic change

- Suppletion

- Toponymy

- Wörter und Sachen

Notes

- The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) ISBN 0-19-861263-X – p. 633 "Etymology /ˌɛtɪˈmɒlədʒi/ the study of the class in words and the way their meanings have changed throughout time".

- Harper, Douglas. "etymology". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ἐτυμολογία, ἔτυμον. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- According to Ghil'ad Zuckermann, the ultimate etymon of the English word machine is the Proto-Indo-European stem *māgh "be able to", see p. 174, Zuckermann, Ghil'ad (2003). Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1403917232.

- According to Ghil'ad Zuckermann, the co-etymon of the Israeli word glida "ice cream" is the Hebrew root gld "clot", see p. 132, Zuckermann, Ghil'ad (2003). Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1403917232.

- The American educator: a library of universal knowledge ..., Volume 3 By Charles Smith Morris, Amos Emerson Dolbear

- Jacobus; Tracy, Larissa (2003). Women of the Gilte Legende: A Selection of Middle English Saints Lives. DS Brewer. ISBN 9780859917711.

- Medieval Sourcebook: The Golden Legend: Volume 2 (full text)

- Szemerényi 1996:6

- "Sir William Jones, British philologist".

References

- Bammesberger, Alfred. English Etymology. Heidelberg: Carl Winter, 1984.

- Barnhart, Robert K. & Sol Steinmetz, eds. Barnhart Dictionary of Etymology. Bronx, NY: H. W. Wilson, 1988.

- Durkin, Philip. The Oxford Guide to Etymology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Liberman, Anatoly. Word Origins...and How We Know Them: Etymology for Everyone. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. (ISBN 0-19-516147-5)

- Mailhammer, Robert, ed. Lexical and Structural Etymology: Beyond Word Histories. Boston–Berlin: de Gruyter Mouton, 2013.

- Malkiel, Yakov. Etymological Dictionaries: A Tentative Typology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976.

- Malkiel, Yakov. Theory and Practice of Romance Etymology. London: Variorum, 1989.

- Malkiel, Yakov. Etymology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Onions, C. T., G. W. S. Friedrichsen, & R. W. Burchfield, eds. Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1966 (many reprints). (ISBN 0-19-861112-9)

- Ross, Alan Strode Campbell. Etymology, with Special Reference to English. London: Deutsch, 1958.

- Seebold, Elmar. Etymologie: Eine Einführung am Beispiel der deutschen Sprache. Munich: Beck, 1981.

- Skeat, Walter W. (2000). The Concise Dictionary of English Etymology, repr ed., Diane. (ISBN 0-7881-9161-6)

- Skeat, Walter W. An Etymological Dictionary of the English Language. 4 vols. Oxford: Clarendon Press; NY: Macmillan, 1879–1882 (rev. and enlarged, 1910). (ISBN 0-19-863104-9)

- Snoj, Marko. "Etymology", in Encyclopedia of Linguistics, vol. 1: A–L. Edited by Philipp Strazny. New York: Fitzroy Dearborn, 2005, pp. 304–6.

- Zuckermann, Ghil'ad (2003). Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1403917232.

External links

| Look up etymology in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Etymology at Curlie.

- List of etymologies of words in 90+ languages.

- Online Etymology Dictionary.