North Germanic languages

The North Germanic languages make up one of the three branches of the Germanic languages—a sub-family of the Indo-European languages—along with the West Germanic languages and the extinct East Germanic languages. The language group is also referred to as the "Nordic languages", a direct translation of the most common term used among Danish, Faroese, Icelandic, Norwegian, and Swedish scholars and laypeople.

| North Germanic | |

|---|---|

| Nordic Scandinavian | |

| Ethnicity | North Germanic peoples |

| Geographic distribution | Northern Europe |

| Linguistic classification | Indo-European

|

| Proto-language | Proto-Norse (attested), later Old Norse |

| Subdivisions |

|

| ISO 639-5 | gmq |

| Glottolog | nort3160[1] |

North Germanic-speaking lands

Continental Scandinavian languages: Insular Nordic languages: Greenlandic Norse (†)

| |

The term "North Germanic languages" is used in comparative linguistics,[2] whereas the term "Scandinavian languages" appears in studies of the modern standard languages and the dialect continuum of Scandinavia.[3][4]

Approximately 20 million people in the Nordic countries speak a Scandinavian language as their native language,[5] including an approximately 5% minority in Finland. Languages belonging to the North Germanic language tree are also commonly spoken in Greenland and, to a lesser extent, by immigrants in North America.

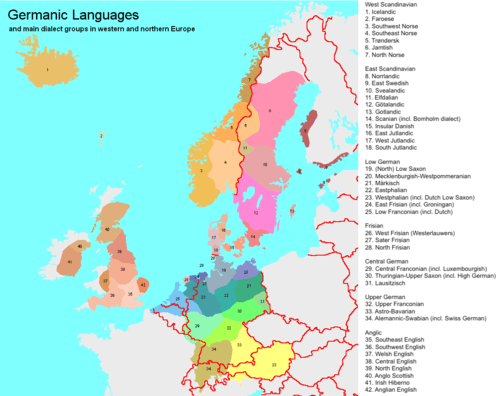

Modern languages and dialects

The modern languages and their dialects in this group are:

- Danish

- Jutlandic dialect

- North Jutlandic

- East Jutlandic

- West Jutlandic

- South Jutlandic

- Insular Danish

- Bornholmsk dialect

- Jutlandic dialect

- Swedish[6]

- South Swedish dialects

- Göta dialects

- Gotland dialects

- Svea dialects

- Norrland dialects

- East Swedish dialects

- Dalecarlian dialects

- Norwegian

- Bokmål (written)

- Nynorsk (written)

- Trønder dialects

- East Norwegian dialects

- West Norwegian dialects

- North Norwegian dialects

- Faroese

- Icelandic

History

Distinction from East and West Germanic

The Germanic languages are traditionally divided into three groups: West, East and North Germanic.[8] Their exact relation is difficult to determine from the sparse evidence of runic inscriptions, and they remained mutually intelligible to some degree during the Migration Period, so that some individual varieties are difficult to classify. Dialects with the features assigned to the northern group formed from the Proto-Germanic language in the late Pre-Roman Iron Age in Northern Europe.

Eventually, around the year 200 AD, speakers of the North Germanic branch became distinguishable from the other Germanic language speakers. The early development of this language branch is attested through runic inscriptions.

Features shared with West Germanic

The North Germanic group is characterized by a number of phonological and morphological innovations shared with West Germanic:

- The retraction of Proto-Germanic ē (/ɛː/, also written ǣ) to ā.[9]

- Proto-Germanic *jērą 'year' > Northwest Germanic *jārą, whence

- North Germanic *āra > Old Norse ár,

- West Germanic *jāra > Old High German jār, Old English ġēar [jæ͡ɑːr] vs. Gothic jēr.

- Proto-Germanic *jērą 'year' > Northwest Germanic *jārą, whence

- The raising of [ɔː] to [oː] (and word-finally to [uː]). The original vowel remained when nasalised *ǭ [ɔ̃ː] and when before /z/, and was then later lowered to [ɑː].

- Proto-Germanic *gebō 'gift' [ˈɣeβɔː] > Northwest Germanic *geƀu, whence

- North Germanic *gjavu > with u-umlaut *gjǫvu > ON gjǫf,

- West Germanic *gebu > OE giefu vs. Gothic giba (vowel lowering).

- Proto-Germanic *tungǭ 'tongue' [ˈtuŋɡɔ̃ː] > late Northwest Germanic *tungā > *tunga > ON tunga, OHG zunga, OE tunge (unstressed a > e) vs. Gothic tuggō.

- Proto-Germanic gen. sg. *gebōz 'of a gift' [ˈɣeβɔːz] > late Northwest Germanic *gebāz, whence

- North Germanic *gjavaz > ON gjafar,

- West Germanic *geba > OHG geba, OE giefe (unstressed a > e) vs. Gothic gibōs.

- Proto-Germanic *gebō 'gift' [ˈɣeβɔː] > Northwest Germanic *geƀu, whence

- The development of i-umlaut.

- The rhotacism of /z/ to /r/, with presumably a rhotic fricative of some kind as an earlier stage.

- This change probably affected West Germanic much earlier and then spread from there to North Germanic, but failed to reach East Germanic which had already split off by that time. This is confirmed by an intermediate stage ʀ, clearly attested in late runic East Norse at a time when West Germanic had long merged the sound with /r/.

- The development of the demonstrative pronoun ancestral to English this.

- Germanic *sa, sō, þat 'this, that' (cf. ON sá m., sú f., þat n.; OE se, sēo, þæt; Gothic sa m., so f., þata n.) + proximal *si 'here' (cf. ON si, OHG sē, Gothic sai 'lo!, behold!’);

- Runic Norse: nom. sg. sa-si, gen. þes-si, dat. þeim-si etc., with declension of the first part;

- fixed form with declension on the second part: ON sjá, þessi m., OHG these m., OE þes m., þēos f., þis n.

- Germanic *sa, sō, þat 'this, that' (cf. ON sá m., sú f., þat n.; OE se, sēo, þæt; Gothic sa m., so f., þata n.) + proximal *si 'here' (cf. ON si, OHG sē, Gothic sai 'lo!, behold!’);

Some have argued that after East Germanic broke off from the group, the remaining Germanic languages, the Northwest Germanic languages, divided into four main dialects:[10] North Germanic, and the three groups conventionally called "West Germanic", namely

- North Sea Germanic (Ingvaeonic languages, ancestral to the Anglo-Frisian languages and Low German),

- Weser-Rhine Germanic (Low Franconian languages) and

- Elbe Germanic (High German languages).

Inability of the tree model to explain the existence of some features in the West Germanic languages stimulated the development of an alternative, the so-called wave model.

Under this view, the properties that the West Germanic languages have in common separate from the North Germanic languages are not inherited from a "Proto-West-Germanic" language, but rather spread by language contact among the Germanic languages spoken in central Europe, not reaching those spoken in Scandinavia.

North Germanic features

Some innovations are not found in West and East Germanic, such as:

- Sharpening of geminate /jj/ and /ww/ according to Holtzmann's law

- Occurred also in East Germanic, but with a different outcome.

- Proto-Germanic *twajjǫ̂ ("of two") > Old Norse tveggja, Gothic twaddjē, but > Old High German zweiio

- Word-final devoicing of stop consonants.

- Proto-Germanic *band ("I/he bound") > *bant > Old West Norse batt, Old East Norse bant, but Old English band

- Loss of medial /h/ with compensatory lengthening of the preceding vowel and the following consonant, if present.

- Proto-Germanic *nahtų ("night", accusative) > *nāttu > (by u-umlaut) *nǭttu > Old Norse nótt

- /ɑi̯/ > /ɑː/ before /r/ (but not /z/)

- Proto-Germanic *sairaz ("sore") > *sāraz > *sārz > Old Norse sárr, but > *seira > Old High German sēr.

- With original /z/ Proto-Germanic *gaizaz > *geizz > Old Norse geirr.

- General loss of word-final /n/, following the loss of word-final short vowels (which are still present in the earliest runic inscriptions).

- Proto-Germanic *bindaną > *bindan > Old Norse binda, but > Old English bindan.

- This also affected stressed syllables: Proto-Germanic *in > Old Norse í

- Vowel breaking of /e/ to /jɑ/ except after w, r or l (see "gift" above).

- The diphthong /eu/ was also affected (also l), shifting to /jɒu/ at an early stage. This diphthong is preserved in Old Gutnish and survives in modern Gutnish. In other Norse dialects, the /j/-onset and length remained, but the diphthong simplified resulting in variously /juː/ or /joː/.

- This affected only stressed syllables. The word *ek ("I"), which could occur both stressed and unstressed, appears varyingly as ek (unstressed, with no breaking) and jak (stressed, with breaking) throughout Old Norse.

- Loss of initial /j/ (see "year" above), and also of /w/ before a round vowel.

- Proto-Germanic *wulfaz > North Germanic ulfz > Old Norse ulfr

- The development of u-umlaut, which rounded stressed vowels when /u/ or /w/ followed in the next syllable. This followed vowel breaking, with ja /jɑ/ being u-umlauted to jǫ /jɒ/.

Middle Ages

After the Old Norse period, the North Germanic languages developed into an East Scandinavian branch, consisting of Danish and Swedish; and, secondly, a West Scandinavian branch, consisting of Norwegian, Faroese and Icelandic and, thirdly, an Old Gutnish branch.[11] Norwegian settlers brought Old West Norse to Iceland and the Faroe Islands around 800. Of the modern Scandinavian languages, written Icelandic is closest to this ancient language.[12] An additional language, known as Norn, developed on Orkney and Shetland after Vikings had settled there around 800, but this language became extinct around 1700.[5]

In medieval times, speakers of all the Scandinavian languages could understand one another to a significant degree, and it was often referred to as a single language, called the "Danish tongue" until the 13th century by some in Sweden[12] and Iceland.[13] In the 16th century, many Danes and Swedes still referred to North Germanic as a single language, which is stated in the introduction to the first Danish translation of the Bible and in Olaus Magnus' A Description of the Northern Peoples. Dialectal variation between west and east in Old Norse however was certainly present during the Middle Ages and three dialects had emerged: Old West Norse, Old East Norse and Old Gutnish. Old Icelandic was essentially identical to Old Norwegian, and together they formed the Old West Norse dialect of Old Norse and were also spoken in settlements in Faroe Islands, Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, and Norwegian settlements in Normandy.[14] The Old East Norse dialect was spoken in Denmark, Sweden, settlements in Russia,[15] England, and Danish settlements in Normandy. The Old Gutnish dialect was spoken in Gotland and in various settlements in the East.

Yet, by 1600, another classification of the North Germanic language branches had arisen from a syntactic point of view,[5] dividing them into an insular group (Icelandic and Faroese) and a continental group (Danish, Norwegian and Swedish). The division between Insular Nordic (önordiska/ønordisk/øynordisk)[16] and Continental Scandinavian (Skandinavisk)[17] is based on mutual intelligibility between the two groups and developed due to different influences, particularly the political union of Denmark and Norway (1536–1814) which led to significant Danish influence on central and eastern Norwegian dialects (Bokmål or Dano-Norwegian).[4]

Demographics

The North Germanic languages are national languages in Denmark, Iceland, Norway and Sweden, whereas the non-Germanic Finnish is spoken by the majority in Finland. In inter-Nordic contexts, texts are today often presented in three versions: Finnish, Icelandic, and one of the three languages Danish, Norwegian and Swedish.[18] Another official language in the Nordic countries is Greenlandic (in the Eskimo–Aleut family), the sole official language of Greenland.

In Southern Jutland in southwestern Denmark, German is also spoken by the North Schleswig Germans, and German is a recognized minority language in this region. German is the primary language among the Danish minority of Southern Schleswig, and likewise, Danish is the primary language of the North Schleswig Germans. Both minority groups are highly bilingual.

Traditionally, Danish and German were the two official languages of Denmark–Norway; laws and other official instruments for use in Denmark and Norway were written in Danish, and local administrators spoke Danish or Norwegian. German was the administrative language of Holstein and the Duchy of Schleswig.

Sami languages form an unrelated group that has coexisted with the North Germanic language group in Scandinavia since prehistory.[19] Sami, like Finnish, is part of the group of the Uralic languages.[20] During centuries of interaction, Finnish and Sami have imported many more loanwords from North Germanic languages than vice versa.

| Language | Speakers | Official Status |

|---|---|---|

| Swedish | 9,200,000* | |

| Danish | 5,600,000 | |

| Norwegian | 5,000,000 | |

| Icelandic | 358,000 | |

| Faroese | 90,000 | |

| Elfdalian | 3,500 | |

| Total | 20,251,500 |

- * The figure includes 450,000 members of the Swedish-speaking population of Finland

Classification

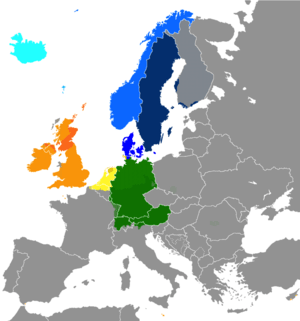

North Germanic languages West Germanic languages Dots indicate a few of the areas where multilingualism is common.

In historical linguistics, the North Germanic family tree is divided into two main branches, West Scandinavian languages (Norwegian, Faroese and Icelandic) and East Scandinavian languages (Danish and Swedish), along with various dialects and varieties. The two branches are derived from the western and eastern dialect groups of Old Norse respectively. There was also an Old Gutnish branch spoken on the island of Gotland. The continental Scandinavian languages (Swedish, Norwegian and Danish) were heavily influenced by Middle Low German during the period of Hanseatic expansion.

Another way of classifying the languages – focusing on mutual intelligibility rather than the tree-of-life model – posits Norwegian, Danish, and Swedish as Continental Scandinavian, and Faroese and Icelandic as Insular Scandinavian.[4] Because of the long political union between Norway and Denmark, moderate and conservative Norwegian Bokmål share most of the Danish vocabulary and grammar, and was nearly identical to written Danish until the spelling reform of 1907. (For this reason, Bokmål and its unofficial, more conservative variant Riksmål are sometimes considered East Scandinavian, and Nynorsk West Scandinavian via the west–east division shown above.)[21]

However, Danish has developed a greater distance between the spoken and written versions of the language, so the differences between spoken Norwegian and spoken Danish are somewhat more significant than the difference between their respective written forms. Written Danish is relatively close to the other Continental Scandinavian languages, but the sound developments of spoken Danish include reduction and assimilation of consonants and vowels, as well as the prosodic feature called stød in Danish, developments which have not occurred in the other languages (though the stød corresponds to the changes in pitch in Norwegian and Swedish, which are pitch-accent languages. Scandinavians are widely expected to understand some of the other spoken Scandinavian languages. There may be some difficulty particularly with elderly dialect speakers, however public radio and television presenters are often well understood by speakers of the other Scandinavian countries, although there are various regional differences of mutual intelligibility for understanding mainstream dialects of the languages between different parts of the three language areas.

Sweden left the Kalmar Union in 1523 due to conflicts with Denmark, leaving two Scandinavian units: The union of Denmark–Norway (ruled from Copenhagen, Denmark) and Sweden (including present-day Finland). The two countries took different sides during several wars until 1814, when the Denmark-Norway unit was disestablished, and made different international contacts. This led to different borrowings from foreign languages (Sweden had a francophone period), for example the Old Swedish word vindöga 'window' was replaced by fönster (from Middle Low German), whereas native vindue was kept in Danish. Norwegians, who spoke (and still speak) the Norwegian dialects derived from Old Norse, would say vindauga or similar. The written language of Denmark-Norway however, was based on the dialect of Copenhagen and thus had vindue. On the other hand, the word begynde 'begin' (now written begynne in Norwegian Bokmål) was borrowed into Danish and Norwegian, whereas native börja was kept in Swedish. Even though standard Swedish and Danish were moving apart, the dialects were not influenced that much. Thus Norwegian and Swedish remained similar in pronunciation, and words like børja were able to survive in some of the Norwegian dialects whereas vindöga survived in some of the Swedish dialects. Nynorsk incorporates much of these words, like byrja (cf. Swedish börja, Danish begynde), veke (cf. Sw vecka, Dan uge) and vatn (Sw vatten, Dan vand) whereas Bokmål has retained the Danish forms (begynne, uke, vann). As a result, Nynorsk does not conform the above east–west split model, since it shares a lot of features with Swedish. According to the Norwegian linguist Arne Torp, the Nynorsk project (which had as a goal to re-establish a written Norwegian language) would have been much harder to carry out if Norway had been in a union with Sweden instead of with Denmark, simply because the differences would have been smaller.[22]

Currently, English loanwords are influencing the languages. A 2005 survey of words used by speakers of the Scandinavian languages showed that the number of English loanwords used in the languages has doubled during the last 30 years and is now 1.2%. Icelandic has imported fewer English words than the other North Germanic languages, despite the fact that it is the country that uses English most.[23]

Mutual intelligibility

The mutual intelligibility between the Continental Scandinavian languages is asymmetrical. Various studies have shown Norwegian speakers to be the best in Scandinavia at understanding other languages within the language group.[24][25] According to a study undertaken during 2002–2005 and funded by the Nordic Cultural Fund, Swedish speakers in Stockholm and Danish speakers in Copenhagen have the greatest difficulty in understanding other Nordic languages.[23] The study, which focused mainly on native speakers under the age of 25, showed that the lowest ability to comprehend another language is demonstrated by youth in Stockholm in regard to Danish, producing the lowest ability score in the survey. The greatest variation in results between participants within the same country was also demonstrated by the Swedish speakers in the study. Participants from Malmö, located in the southernmost Swedish province of Scania (Skåne), demonstrated a better understanding of Danish than Swedish speakers to the north.

Access to Danish television and radio, direct trains to Copenhagen over the Øresund Bridge and a larger number of cross-border commuters in the Øresund Region contribute to a better knowledge of spoken Danish and a better knowledge of the unique Danish words among the region's inhabitants. According to the study, youth in this region were able to understand the Danish language (slightly) better than the Norwegian language. But they still could not understand Danish as well as the Norwegians could, demonstrating once again the relative distance of Swedish from Danish. Youth in Copenhagen had a very poor command of Swedish, showing that the Øresund connection was mostly one-way.

The results from the study of how well native youth in different Scandinavian cities did when tested on their knowledge of the other Continental Scandinavian languages are summarized in table format,[24] reproduced below. The maximum score was 10.0:

| City | Comprehension of Danish |

Comprehension of Swedish |

Comprehension of Norwegian |

Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Århus, Denmark | N/A | 3.74 | 4.68 | 4.21 |

| Copenhagen, Denmark | N/A | 3.60 | 4.13 | 3.87 |

| Malmö, Sweden | 5.08 | N/A | 4.97 | 5.02 |

| Stockholm, Sweden | 3.46 | N/A | 5.56 | 4.51 |

| Bergen, Norway | 6.50 | 6.15 | N/A | 6.32 |

| Oslo, Norway | 6.57 | 7.12 | N/A | 6.85 |

Faroese speakers (of the Insular Scandinavian languages group) are even better than the Norwegians at comprehending two or more languages within the Continental Scandinavian languages group, scoring high in both Danish (which they study at school) and Norwegian and having the highest score on a Scandinavian language other than their native language, as well as the highest average score. Icelandic speakers, in contrast, have a poor command of Norwegian and Swedish. They do somewhat better with Danish, as they are taught Danish in school. When speakers of Faroese and Icelandic were tested on how well they understood the three Continental Scandinavian languages, the test results were as follows (maximum score 10.0):[24]

| Area/ Country |

Comprehension of Danish |

Comprehension of Swedish |

Comprehension of Norwegian |

Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Faroe Islands | 8.28 | 5.75 | 7.00 | 7.01 |

| Iceland | 5.36 | 3.34 | 3.40 | 4.19 |

Vocabulary

The North Germanic languages share many lexical, grammatical, phonological, and morphological similarities, to a more significant extent than the West Germanic languages do. These lexical, grammatical, and morphological similarities can be outlined in the table below.

| Language | Sentence |

|---|---|

| English | It was a humid, grey summer day at the end of June. |

| Frisian | It wie in stribbelige/fochtige, graue simmerdei oan de ein fan Juny. |

| Low Saxon | Dat weer/was een vuchtige, griese Summerdag an't Enn vun Juni. |

| Afrikaans | Dit was 'n vogtige, grou somer dag aan die einde van Junie. |

| Dutch | Het was een vochtige, grauwe zomerdag eind juni. |

| German | Es war ein feuchter, grauer Sommertag Ende Juni. |

| Swedish | Det var en fuktig, grå sommardag i slutet av juni. |

| Danish | Det var en fugtig, grå sommerdag i slutningen af juni. |

| Norwegian (Bokmål) | Det var en fuktig, grå sommerdag i slutten av juni. |

| Norwegian (Nynorsk) | Det var ein fuktig, grå sommardag i slutten av juni. |

| Icelandic | Það var rakur, grár sumardagur í lok júní. |

| Faroese | Tað var ein rakur, gráur summardagur síðst í juni. |

Language boundaries

Given the aforementioned homogeneity, there exists some discussion on whether the continental group should be considered one or several languages.[26] The Scandinavian languages (in the narrow sense, i.e. the languages of Scandinavia) are often cited as proof of the aphorism "A language is a dialect with an army and navy". The differences in dialects within the countries of Norway, Sweden, and Denmark can often be greater than the differences across the borders, but the political independence of these countries leads continental Scandinavian to be classified into Norwegian, Swedish, and Danish in the popular mind as well as among most linguists. The generally agreed upon language border is, in other words, politically shaped. This is also because of the strong influence of the standard languages, particularly in Denmark and Sweden.[26] Even if the language policy of Norway has been more tolerant of rural dialectal variation in formal language, the prestige dialect often referred to as "Eastern Urban Norwegian", spoken mainly in and around the Oslo region, is sometimes considered normative. The influence of a standard Norwegian is nevertheless less so than in Denmark and Sweden, since the prestige dialect in Norway has moved geographically several times over the past 200 years. The organised formation of Nynorsk out of western Norwegian dialects after Norway became independent from Denmark in 1814 intensified the politico-linguistic divisions.

The Nordic Council has on several occasions referred to the (Germanic) languages spoken in Scandinavia as the "Scandinavian language" (singular); for instance, the official newsletter of the Nordic Council is written in the "Scandinavian language".[27] The creation of one unified written language has been considered as highly unlikely, given the failure to agree upon a common standardized language in Norway. However, there is a slight chance of "some uniformization of spelling" between Norway, Sweden and Denmark.[28][29]

Family tree

All North Germanic languages are descended from Old Norse. Divisions between subfamilies of North Germanic are rarely precisely defined: Most form continuous clines, with adjacent dialects being mutually intelligible and the most separated ones not.

- Old Norse

- West Scandinavian

- Faroese

- Greenlandic Norse (extinct)

- Icelandic

- Norn (extinct)

- Norwegian

- Nordnorsk (Northern Norway)

- Bodø dialect (Bodø)

- Brønnøy dialect (Brønnøy)

- Helgeland dialect (Helgeland)

- other dialects

- Trøndersk (Trøndelag)

- Fosen dialect (Fosen)

- Härjedal dialect (Härjedalen)

- Jämtland dialects (Jämtland province) (Wide linguistic similarity with the Trøndersk dialects in Norway)

- Meldal dialect (Meldal)

- Tydal dialect (Tydal)

- other dialects

- Vestlandsk (Western and Southern Norway)

- West (Vestlandet)

- Bergen dialect (Bergen)

- Haugesund dialect (Haugesund)

- Jærsk dialect (Jæren district)

- Karmøy dialect (Karmøy)

- Nordmøre dialects (Nordmøre)

- Sunndalsøra dialect (Sunndalsøra)

- Romsdal dialect (Romsdal)

- Sandnes dialect (Sandnes)

- Sogn dialect (Sogn district)

- Sunnmøre dialect (Sunnmøre)

- Stavanger dialect (Stavanger)

- Strilar dialect (Midhordland district)

- South (Sørlandet)

- Arendal dialect (Arendal region)

- Valle-Setesdalsk dialect (Upper Setesdal, Valle)

- other dialects

- West (Vestlandet)

- Østlandsk (Eastern Norway)

- Flatbygd dialects (Lowland districts)

- Vikværsk dialects (Viken district)

- Andebu dialect (Andebu)

- Bohuslän dialect (Bohuslän province) (Influenced by Swedish in retrospective)

- Grenland dialect (Grenland district)

- Oslo dialect (Oslo)

- Midtøstland dialects (Mid-east districts)

- Ringerike dialects (Ringerike district)

- Oppland dialect (Opplandene district)

- Hadeland dialect (Hadeland district)

- Østerdal dialect (Viken district)

- Särna-Idre dialect (Särna and Idre)

- Vikværsk dialects (Viken district)

- Midland dialects (Midland districts)

- Gudbrandsdal dialect (Gudbrandsdalen, Oppland and Upper Folldal, Hedmark)

- Hallingdal-Valdres dialects (Hallingdal, Valdres)

- Hallingdal dialect

- Valdris dialect (Valdres district)

- Telemark-Numedal dialects (Telemark and Numedal)

- Bø dialect

- other dialects

- Flatbygd dialects (Lowland districts)

- Nordnorsk (Northern Norway)

- Dalecarlian (Dalarna), including Elfdalian (which is considered a separate language from Swedish, Älvdalen locality)[7]

- East Scandinavian

- Danish

- Insular Danish (Ømål)

- East Danish (Bornholmsk along with former East Danish dialects in Blekinge, Halland and Skåne (Scanian dialect) as well as the southern parts of Småland, now generally considered South Swedish dialects)

- Jutlandic (or Jutish, in Jutland)

- Northern Jutlandic

- East Jutlandic

- West Jutlandic

- Southern Jutlandic (in Southern Jutland and Southern Schleswig)

- Northern Jutlandic

- Urban East Norwegian (generally considered a Norwegian dialect)

- Swedish

- Sveamål (Svealand)

- Norrland dialects (Norrland, including Westrobothnian and Kalix)

- Götamål (Götaland)

- Swedish dialects in Ostrobothnia (Finland and Estonia)

- Gutnish (Gotland)

- other dialects

- Danish

- West Scandinavian

Classification difficulties

The Jamtlandic dialects share many characteristics with both Trøndersk and with Norrländska mål. Due to this ambiguous position, it is contested whether Jamtlandic belongs to the West Scandinavian or the East Scandinavian group.[30]

Elfdalian (Älvdalen speech), generally considered a Sveamål dialect, today has an official orthography and is, because of a lack of mutual intelligibility with Swedish, considered as a separate language by many linguists. Traditionally regarded as a Swedish dialect,[31] but by several criteria closer to West Scandinavian dialects,[7] Elfdalian is a separate language by the standard of mutual intelligibility.[32][33][34][35]

Traveller Danish, Rodi, and Swedish Romani are varieties of Danish, Norwegian and Swedish with Romani vocabulary or Para-Romani known collectively as the Scandoromani language.[36] They are spoken by Norwegian and Swedish Travellers. The Scando-Romani varieties in Sweden and Norway combine elements from the dialects of Western Sweden, Eastern Norway (Østlandet) and Trøndersk.

Written norms of Norwegian

Norwegian has two official written norms, Bokmål and Nynorsk. In addition, there are some unofficial norms. Riksmål is more conservative than Bokmål (that is, closer to Danish) and is used to various extents by numerous people, especially in the cities and by the largest newspaper in Norway, Aftenposten. On the other hand, Høgnorsk (High Norwegian) is similar to Nynorsk and is used by a very small minority.

See also

- Comparison of Norwegian Bokmål and Standard Danish

- Ingvaeonic languages

- Low Franconian languages

- Gender in Danish and Swedish

- High German languages

- Scanian dialect

- Svorsk

- East Germanic languages

- West Germanic languages

- South Germanic languages

References

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "North Germanic". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.), 2005. Language Family Trees Indo-European, Germanic, North. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition. Dallas, Texas: SIL International

- Scandinavian Dialect Syntax. Network for Scandinavian Dialect Syntax. Retrieved 11 November 2007.

- Torp, Arne (2004). Nordiske sprog i fortid og nutid. Sproglighed og sprogforskelle, sprogfamilier og sprogslægtskab Archived 4 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Moderne nordiske sprog. In Nordens sprog – med rødder og fødder. Nord 2004:010, ISBN 92-893-1041-3, Nordic Council of Ministers' Secretariat, Copenhagen 2004. (In Danish).

- Holmberg, Anders and Christer Platzack (2005). "The Scandinavian languages". In The Comparative Syntax Handbook, eds Guglielmo Cinque and Richard S. Kayne. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. Excerpt at Durham University Archived 3 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- Leinonen, Therese (2011), "Aggregate analysis of vowel pronunciation in Swedish dialects", Oslo Studies in Language 3 (2) Aggregate analysis of vowel pronunciation in Swedish dialects]", Oslo Studies in Language 3 (2); Dahl, Östen (2000), Språkets enhet och mångfald., Lund: Studentlitteratur, pp. 117–119; Lars-Erik Edlund "Språklig variation i tid och rum" in Dahl, Östen & Edlund, Lars-Erik, eds. (2010), Sveriges nationalatlas. Språken i Sverige.Stockholm: Kungl. Vitterhets historie och antikvitets akademien, p. 9

- Kroonen, Guus. "On the origins of the Elfdalian nasal vowels from the perspective of diachronic dialectology and Germanic etymology" (PDF). Department of Nordic Studies and Linguistics. University of Copenhagen. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

In many aspects, Elfdalian, takes up a middle position between East and West Nordic. However, it shares some innovations with West Nordic, but none with East Nordic. This invalidates the claim that Elfdalian split off from Old Swedish.

- Hawkins, John A. (1987). "Germanic languages". In Bernard Comrie (ed.). The World's Major Languages. Oxford University Press. pp. 68–76. ISBN 0-19-520521-9.

- But see Cercignani, Fausto, Indo-European ē in Germanic, in «Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung», 86/1, 1972, pp. 104–110.

- Kuhn, Hans (1955–56). "Zur Gliederung der germanischen Sprachen". Zeitschrift für deutsches Altertum und deutsche Literatur. 86: 1–47.

- Bandle, Oskar (ed.)(2005). The Nordic Languages: An International Handbook of the History of the North Germanic Languages. Walter de Gruyter, 2005, ISBN 3-11-017149-X.

- Lund, Jørn. Language Archived 15 August 2004 at the Wayback Machine. Published online by Royal Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Version 1 – November 2003. Retrieved 13 November 2007.

- Lindström, Fredrik; Lindström, Henrik (2012). Svitjods undergång och Sveriges födelse. Albert Bonniers Förlag. ISBN 978-91-0-013451-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link), p. 259

- Adams 1895, pp. 336–338.

- Article Nordiska språk, section Historia, subsection Omkring 800–1100, in Nationalencyklopedin (1994).

- Jónsson, Jóhannes Gísli and Thórhallur Eythórsson (2004). "Variation in subject case marking in Insular Scandinavian". Nordic Journal of Linguistics (2005), 28: 223–245 Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 9 November 2007.

- Heine, Bernd and Tania Kuteva (2006). The Changing Languages of Europe. Oxford University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-19-929734-7.

- The Nordic Council's/Nordic Council of Ministers' political magazine Analys Norden offers three versions: a section labeled "Íslenska" (Icelandic), a section labeled "Skandinavisk" (in either Danish, Norwegian or Swedish), and a section labeled "Suomi" (Finnish).

- Sammallahti, Pekka, 1990. "The Sámi Language: Past and Present". In Arctic Languages: An Awakening. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Paris. ISBN 92-3-102661-5, p. 440: "the arrival of a Uralic population and language in Samiland [...] means that there has been a period of at least 5000 years of uninterrupted linguistic and cultural development in Samiland. [...] It is also possible, however, that the earlier inhabitants of the area also spoke a Uralic language: we do not know of any linguistic groups in the area other than the Uralic and Indo-Europeans (represented by the present Scandinavian languages)."

- Inez Svonni Fjällström (2006). "A language with deep roots" Archived 5 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine.Sápmi: Language history, 14 November 2006. Samiskt Informationscentrum Sametinget: "The Scandinavian languages are Northern Germanic languages. [...] Sami belongs to the Finno-Ugric language family. Finnish, Estonian, Livonian and Hungarian belong to the same language family and are consequently related to each other."

- Victor Ginsburgh, Shlomo Weber (2011). How many languages do we need?: the economics of linguistic diversity, Princeton University Press. p. 42.

- http://www.uniforum.uio.no/nyheter/2005/03/nynorsk-noe-for-svensker.html

- "Urban misunderstandings". In Norden this week – Monday 01.17.2005. The Nordic Council and the Nordic Council of Ministers. Retrieved 13 November 2007.

- Delsing, Lars-Olof and Katarina Lundin Åkesson (2005). Håller språket ihop Norden? En forskningsrapport om ungdomars förståelse av danska, svenska och norska. Available in pdf format Archived 14 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Numbers are from Figure 4:11. "Grannspråksförståelse bland infödda skandinaver fördelade på ort", p. 65 and Figure 4:6. "Sammanlagt resultat på grannspråksundersökningen fördelat på område", p. 58.

- Maurud, Ø (1976). Nabospråksforståelse i Skandinavia. En undersøkelse om gjensidig forståelse av tale- og skriftspråk i Danmark, Norge og Sverige. Nordisk utredningsserie 13. Nordiska rådet, Stockholm.

- Nordens språk – med rötter och fötter

- Hello Norden newsletter's language of publication is described as skandinaviska (in Swedish)

- The Scandinavian Languages: Their Histories and Relationships

- Finlandssvensk som hovedspråk (in Norwegian bokmål)

- Dalen, Arnold (2005). Jemtsk og trøndersk – to nære slektningar Archived 18 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Språkrådet, Norway. (In Norwegian). Retrieved 13 November 2007.

- Ekberg, Lena (2010). "The National Minority Languages in Sweden". In Gerhard Stickel (ed.). National, Regional and Minority Languages in Europe: Contributions to the Annual Conference 2009 of Efnil in Dublin. Peter Lang. pp. 87–92. ISBN 9783631603659.

- Dahl, Östen; Dahlberg, Ingrid; Delsing, Lars-Olof; Halvarsson, Herbert; Larsson, Gösta; Nyström, Gunnar; Olsson, Rut; Sapir, Yair; Steensland, Lars; Williams, Henrik (8 February 2007). "Älvdalskan är ett språk – inte en svensk dialekt" [Elfdalian is a language – not a Swedish dialect]. Aftonbladet (in Swedish). Stockholm. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- Dahl, Östen (December 2008). "Älvdalska – eget språk eller värsting bland dialekter?" [Elfdalian – its own language or an outstanding dialect?]. Språktidningen (in Swedish). Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- Zach, Kristine (2013). "Das Älvdalische – Sprache oder Dialekt? (Diplomarbeit)" [Elfdalian – Language or dialect? (Masters thesis)] (PDF) (in German). University of Vienna.

- Sapir, Yair (2004). Elfdalian, the Vernacular of Övdaln. Conference paper, 18–19 juni 2004. Available in pdf format at Uppsala University online archive Archived 22 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- LLOW – Traveller Danish

Sources

- Adams, Charles Kendall (1895). Johnson's Universal Cyclopedia: A New Edition. D. Appleton, A. J. Johnson.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jervelund, Anita (2007), Sådan Staver Vi.

- Kristiansen, Tore m.fl. (1996), Dansk Sproglære.

- Lucazin, M (2010), Utkast till ortografi över skånska språket med morfologi och ordlista. Första. revisionen (PDF), ISBN 978-91-977265-2-8, archived from the original (PDF) on 8 August 2011, retrieved 21 January 2011 Outlined Scanian orthography including morphology and word index. First revision.

- Maurer, Friedrich (1942), Nordgermanen und Alemannen: Studien zur germanischen und frühdeutschen Sprachgeschichte, Stammes- und Volkskunde, Strasbourg: Hünenburg.

- Rowe, Charley. The problematic Holtzmann's Law in Germanic. (Indogermanische Forschungen Bd. 108, 2003).

- Iben Stampe Sletten red., Nordens sprog – med rødder og fødder, 2005, ISBN 92-893-1041-3, available online, also available in the other Scandinavian languages.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Scandinavian Languages. |