Saxony

Saxony (German: Sachsen [ˌzaksn̩] (![]()

Free State of Saxony Freistaat Sachsen | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: Sachsenlied | |

| |

| Coordinates: 51°1′37″N 13°21′32″E | |

| Country | Germany |

| Largest city | Leipzig |

| Capital | Dresden |

| Government | |

| • Body | Landtag of the Free State of Saxony |

| • Minister-President | Michael Kretschmer (CDU) |

| • Governing parties | CDU / Greens / SPD |

| • Bundesrat votes | 4 (of 69) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 18,415.66 km2 (7,110.33 sq mi) |

| Population (31 December 2018) | |

| • Total | 4,077,937 |

| • Density | 220/km2 (570/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| ISO 3166 code | DE-SN |

| GRP (nominal) | €128 billion (2019)[1] |

| GRP per capita | €31,000 (2019) |

| NUTS Region | DED |

| HDI (2018) | 0.930[2] very high · 9th of 16 |

| Website | sachsen.de |

The history of Saxony spans more than a millennium. It has been a medieval duchy, an electorate of the Holy Roman Empire, a kingdom, and twice a republic. The first Free State of Saxony was established in 1918 as a constituent state of the Weimar Republic. After World War II, it became part of the German Democratic Republic and was abolished by the communist government in 1952. Following German reunification, the Free State of Saxony was reconstituted with slightly altered borders in 1990 and became one of the Federal Republic of Germany's new states.

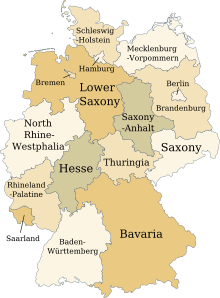

The area of the modern state of Saxony should not be confused with Old Saxony, the area inhabited by Saxons. Old Saxony corresponds roughly to the modern German states of Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and the Westphalian part of North Rhine-Westphalia.

History

Saxony has a long history as a duchy, an electorate of the Holy Roman Empire (the Electorate of Saxony), and finally as a kingdom (the Kingdom of Saxony). In 1918, after Germany's defeat in World War I, its monarchy was overthrown and a republican form of government was established under the current name. The state was broken up into smaller units during communist rule (1949–1989), but was re-established on 3 October 1990 on the reunification of East and West Germany.

Prehistory

In prehistoric times, the territory of present-day Saxony was the site of some of the largest of the ancient central European monumental temples, dating from the fifth century BC. Notable archaeological sites have been discovered in Dresden and the villages of Eythra and Zwenkau near Leipzig. The Slavic and Germanic presence in the territory of today's Saxony is thought to have begun in the first century BC.

Parts of Saxony were possibly under the control of the Germanic King Marobod during the Roman era. By the late Roman period, several tribes known as the Saxons emerged, from which the subsequent state(s) draw their name.

Duchy of Saxony

The first medieval Duchy of Saxony was a late Early Middle Ages "Carolingian stem duchy", which emerged around the start of the 8th century AD and grew to include the greater part of Northern Germany, what are now the modern German states of Bremen, Hamburg, Lower Saxony, North Rhine-Westphalia, Schleswig-Holstein and Saxony-Anhalt. The Saxons converted to Christianity during this period. This geographical region is unrelated to present-day Saxony but the name moved southwards due to certain historical events (see below).

The territory of the Free State of Saxony, called White Serbia was, since the 5th century, populated by Slavs before being conquered by Germans e.g. Saxons and Thuringii. It was not part of the old Saxon stem duchy. A legacy of this period is the Sorb population in Saxony. Eastern parts of present Saxony were ruled by Poland between 1002 and 1032 and by Bohemia since 1293.

Holy Roman Empire

The territory of the Free State of Saxony became part of the Holy Roman Empire by the 10th century, when the dukes of Saxony were also kings (or emperors) of the Holy Roman Empire, comprising the Ottonian, or Saxon, Dynasty. Around this time, the Billungs, a Saxon noble family, received extensive fields in Saxony. The emperor eventually gave them the title of dukes of Saxony. After Duke Magnus died in 1106, causing the extinction of the male line of Billungs, oversight of the duchy was given to Lothar of Supplinburg, who also became emperor for a short time.

The Margravate of Meissen was founded in 985 as a frontier march, that soon extended to the Kwisa (Queis) river to the east and as far as the Ore Mountains. In the process of Ostsiedlung, settlement of German farmers in the sparsely populated area was promoted.

In 1137, control of Saxony passed to the Guelph dynasty, descendants of Wulfhild Billung, eldest daughter of the last Billung duke, and the daughter of Lothar of Supplinburg. In 1180 large portions west of the Weser were ceded to the Bishops of Cologne, while some central parts between the Weser and the Elbe remained with the Guelphs, becoming later the Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg. The remaining eastern lands, together with the title of Duke of Saxony, passed to an Ascanian dynasty (descended from Eilika Billung, Wulfhild's younger sister) and were divided in 1260 into the two small states of Saxe-Lauenburg and Saxe-Wittenberg. The former state was also named Lower Saxony, the latter Upper Saxony, thence the later names of the two Imperial Circles Saxe-Lauenburg and Saxe-Wittenberg. Both claimed the Saxon electoral privilege for themselves, but the Golden Bull of 1356 accepted only Wittenberg's claim, with Lauenburg nevertheless continuing to maintain its claim. In 1422, when the Saxon electoral line of the Ascanians became extinct, the Ascanian Eric V of Saxe-Lauenburg tried to reunite the Saxon duchies.

However, Sigismund, King of the Romans, had already granted Margrave Frederick IV the Warlike of Meissen (House of Wettin) an expectancy of the Saxon electorate in order to remunerate his military support. On 1 August 1425 Sigismund enfeoffed the Wettinian Frederick as Prince-Elector of Saxony, despite the protests of Eric V. Thus the Saxon territories remained permanently separated.

The Electorate of Saxony was then merged with the much bigger Wettinian Margraviate of Meissen, however using the higher-ranking name Electorate of Saxony and even the Ascanian coat-of-arms for the entire monarchy.[3] Thus Saxony came to include Dresden and Meissen. Hence, the territory of the Freestate of Saxony today is for historical and dynastic reasons sharing the name with the old Saxon stem duchy but without a significant ethnic relationship, neither by descent, language nor by culture. In the 18th and 19th centuries Saxe-Lauenburg was colloquially called the Duchy of Lauenburg, which in 1876 merged with Prussia as the Duchy of Lauenburg district.

Foundation of the second Saxon state

.svg.png)

Saxony-Wittenberg, in modern Saxony-Anhalt, became subject to the margravate of Meissen, ruled by the Wettin dynasty in 1423. This established a new and powerful state, occupying large portions of the present Free State of Saxony, Thuringia, Saxony-Anhalt and Bavaria (Coburg and its environs). Although the centre of this state was far to the southeast of the former Saxony, it came to be referred to as Upper Saxony and then simply Saxony, while the former Saxon territories in the north were now known as Lower Saxony (the modern term Niedersachsen deriving from this).

In 1485, Saxony was split in the Treaty of Leipzig. A collateral line of the Wettin princes received what later became Thuringia and founded several small states there (see Ernestine duchies). Since these princes were allowed to use the Saxon coat of arms, in many towns of Thuringia, the coat of arms can still be found on historical buildings.

The remaining Saxon state became still more powerful, also incorporating new territories and was known in the 18th century for its cultural achievements, although it was politically weaker than Prussia and Austria, states which oppressed Saxony from the north and south, respectively.

Between 1697 and 1763, the Electors of Saxony were also elected Kings of Poland in personal union.

In 1756, Saxony joined a coalition of Austria, France and Russia against Prussia. Frederick II of Prussia chose to attack preemptively and invaded Saxony in August 1756, precipitating the Third Silesian War (part of the Seven Years' War). The Prussians quickly defeated Saxony and incorporated the Saxon army into the Prussian army. At the end of the Seven Years' War, Saxony recovered its independence in the 1763 Treaty of Hubertusburg.

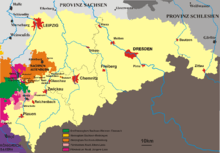

19th century

In 1806, French Emperor Napoleon abolished the Holy Roman Empire and established the Electorate of Saxony as a kingdom in exchange for military support. The Elector Frederick Augustus III accordingly became King Frederick Augustus I of Saxony. Frederick Augustus remained loyal to Napoleon during the wars that swept Europe in the following years; he was taken prisoner and his territories declared forfeit by the allies in 1813, after the defeat of Napoleon. Prussia intended the annexation of Saxony but the opposition of Austria, France, and the United Kingdom to this plan resulted in the restoration of Frederick Augustus to his throne at the Congress of Vienna although he was forced to cede the northern part of the kingdom to Prussia, which led to the loss of nearly 50% of the Saxon territory.[4] These lands became the Prussian province of Saxony, now incorporated in the modern state of Saxony-Anhalt, except the westernmost part around Bad Langensalza, now in the state of Thuringia. Also Lower Lusatia became part of Province of Brandenburg and northeastern part of Upper Lusatia became part of Silesia Province. The remnant of the Kingdom of Saxony was roughly identical with the present state, albeit slightly smaller.

Meanwhile, in 1815, the southern part of Saxony, now called the "State of Saxony" joined the German Confederation.[5] (This German Confederation should not be confused with the North German Confederation mentioned below.) In the politics of the Confederation, Saxony was overshadowed by Prussia. King Anthony of Saxony came to the throne of Saxony in 1827. Shortly thereafter, liberal pressures in Saxony mounted and broke out in revolt during 1830—a year of revolution in Europe.[5] The revolution in Saxony resulted in a constitution for the State of Saxony that served as the basis for its government until 1918.[5]

During the 1848–49 constitutionalist revolutions in Germany, Saxony became a hotbed of revolutionaries, with anarchists such as Mikhail Bakunin and democrats including Richard Wagner and Gottfried Semper taking part in the May Uprising in Dresden in 1849. (Scenes of Richard Wagner's participation in the May 1849 uprising in Dresden are depicted in the 1983 movie Wagner starring Richard Burton as Richard Wagner.) The May uprising in Dresden forced King Frederick Augustus II of Saxony to concede further reforms to the Saxon government.[5]

In 1854 Frederick Augustus II's brother, King John of Saxony, succeeded to the throne. A scholar, King John translated Dante.[5] King John followed a federalistic and pro-Austrian policy throughout the early 1860s until the outbreak of the Austro-Prussian War. During that war, Prussian troops overran Saxony without resistance and then invaded Austrian (today's Czech) Bohemia.[6] After the war, Saxony was forced to pay an indemnity and to join the North German Confederation in 1867.[7] Under the terms of the North German Confederation, Prussia took over control of the Saxon postal system, railroads, military and foreign affairs.[7] In the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, Saxon troops fought together with Prussian and other German troops against France.[7] In 1871, Saxony joined the newly formed German Empire.[7]

20th century

After King Frederick Augustus III of Saxony abdicated on 13 November 1918, Saxony, remaining a constituent state of Germany (Weimar Republic), became the Free State of Saxony under a new constitution enacted on 1 November 1920. In October 1923 the federal government under Chancellor Gustav Stresemann overthrew the legally elected SPD-Communist coalition government of Saxony. The state retained its name and borders during the Nazi era as a Gau (Gau Saxony), but lost its quasi-autonomous status and its parliamentary democracy.

As World War II drew to its end, U.S. troops under General George Patton occupied the western part of Saxony in April 1945, while Soviet troops occupied the eastern part. That summer, the entire state was handed over to Soviet forces as agreed in the London Protocol of September 1944. Britain, the US, and the USSR then negotiated Germany's future at the Potsdam Conference. Under the Potsdam Agreement, all German territory East of the Oder-Neisse line was annexed by Poland and the Soviet Union, and, unlike in the aftermath of World War I, the annexing powers were allowed to expel the inhabitants. During the following three years, Poland and Czechoslovakia forcibly expelled German-speaking people from their territories, and some of these expellees came to Saxony. Only a small area of Saxony lying east of the Neisse River and centred around the town of Reichenau (now called Bogatynia), was annexed by Poland. The Soviet Military Administration in Germany (SVAG) merged that very small part of the Prussian province of Lower Silesia that remained in Germany with Saxony.

Traditional close relations of Saxony with neighouring German-speaking Egerland was thus completely destroyed, making the border of Saxony along the Ore Mountains a linguistic border.

On 20 October 1946, SVAG organised elections for the Saxon state parliament (Landtag), but many people were arbitrarily excluded from candidacy and suffrage, and the Soviet Union openly supported the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED). The new minister-president Rudolf Friedrichs (SED), had been a member of the SPD until April 1946. He met his Bavarian counterparts in the U.S. zone of occupation in October 1946 and May 1947, but died suddenly in mysterious circumstances the following month. He was succeeded by Max Seydewitz, a loyal follower of Joseph Stalin.

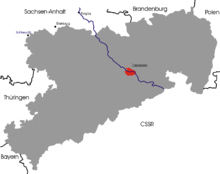

The German Democratic Republic (East Germany), including Saxony, was established in 1949 out of the Soviet zone of Occupied Germany, becoming a constitutionally socialist state, part of COMECON and the Warsaw Pact, under the leadership of the SED. In 1952 the government abolished the Free State of Saxony, and divided its territory into three Bezirke: Leipzig, Dresden, and Karl-Marx-Stadt (formerly and currently Chemnitz). Areas around Hoyerswerda were also part of the Cottbus Bezirk.

The Free State of Saxony was reconstituted with slightly altered borders in 1990, following German reunification. Besides the formerly Silesian area of Saxony, which was mostly included in the territory of the new Saxony, the free state gained further areas north of Leipzig that had belonged to Saxony-Anhalt until 1952.

Geography

Topography

The highest mountain in Saxony is the Fichtelberg (1,215 m) in the Western Ore Mountains.

Rivers

There are numerous rivers in Saxony. The Elbe is the most dominant one. The Neisse defines the border between Saxony and Poland. Other rivers include the Mulde and the White Elster.

Largest cities and towns

The largest cities and towns in Saxony according to the 30 September 2018 estimate are listed below.[8] To this can be added that Leipzig forms a metropolitan-like region with Halle, known as Ballungsraum Leipzig/Halle.[9] The latter city is located just across the border of Saxony-Anhalt. Leipzig shares, for instance, an S-train system (known as S-Bahn Mitteldeutschland)[10] and an airport[11] with Halle.

| Rank | City | Population |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Leipzig | 584,775 |

| 2 | Dresden | 553,128 |

| 3 | Chemnitz | 247,191 |

| 4 | Zwickau | 89,764 |

| 5 | Plauen | 65,051 |

| 6 | Görlitz | 56,265 |

| 7 | Freiberg | 40,893 |

| 8 | Freital | 39,529 |

| 9 | Bautzen | 39,262 |

| 10 | Pirna | 38,366 |

Governance

Politics

Saxony is a parliamentary democracy. A Minister President heads the government of Saxony. Michael Kretschmer has been Minister President since 13 December 2017.

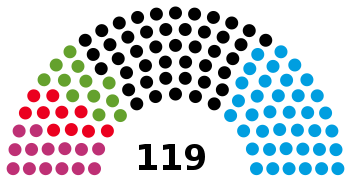

2019 state election

In the 2019 state election the AfD received its highest share of the vote in any state or federal election, while the CDU and The Left both fell to record lows in Saxony. The CDU formed a government coalition with the Greens and the SPD.

Summary of the 1 September 2019 election results[12] for the Landtag of Saxony

| ||||||||

| Party | Ideology | Votes | Votes % (change) | Seats (change) | Seats % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christian Democratic Union (CDU) | Christian democracy | 695,560 | 32.1% | −7.3pp | 45 | −14 | 37.8% | |

| Alternative for Germany (AfD) | German nationalism | 595,671 | 27.5% | +17.7pp | 38 | +24 | 31.9% | |

| The Left (Die Linke) | Democratic socialism | 224,354 | 10.4% | −8.5pp | 14 | −13 | 11.8% | |

| Alliance '90/The Greens (Grünen) | Green politics | 187,015 | 8.6% | +2.9pp | 12 | +4 | 10.1% | |

| Social Democratic Party (SPD) | Social democracy | 167,289 | 7.7% | −4.6pp | 10 | −8 | 8.4% | |

| Free Democratic Party (FDP) | Liberalism | 97,438 | 4.5% | +0.7pp | 0 | ±0 | 0% | |

| Free Voters | Direct democracy | 72,897 | 3.4% | +1.8pp | 0 | ±0 | 0% | |

| Others | 126,233 | 5.8% | −2.7pp | 0 | ±0 | 0% | ||

| Total | 2,166,457 | 100.0% | 119 | −7 | 100.0% | |||

| Blank and invalid votes | 22,029 | 1.02 | ||||||

| Registered voters / turnout | 3,288,643 | 66.5 | ||||||

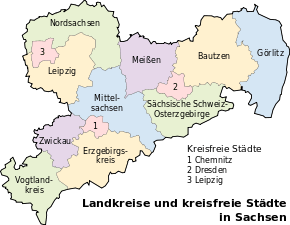

Administration

Saxony is divided into 10 districts:

1. Bautzen (BZ)

2. Erzgebirgskreis (ERZ)

3. Görlitz (GR)

4. Leipzig (L)

5. Meissen (MEI) (Meissen)

6. Mittelsachsen (FG)

7. Nordsachsen (TDO)

8. Sächsische Schweiz-Osterzgebirge (PIR)

9. Vogtlandkreis (V)

10. Zwickau (Z)

In addition, three cities have the status of an urban district (German: kreisfreie Städte):

Between 1990 and 2008, Saxony was divided into the three regions (Regierungsbezirke) of Chemnitz, Dresden, and Leipzig. After a reform in 2008, these regions - with some alterations of their respective areas - were called Direktionsbezirke. In 2012, the authorities of these regions were merged into one central authority, the Landesdirektion Sachsen.

Demographics

Population change

Saxony is a densely populated state if compared with more rural German states such as Bavaria or Lower Saxony. However, the population has declined over time. The population of Saxony began declining in the 1950s due to emigration, a process which accelerated after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. After bottoming out in 2013, the population has stabilized thanks to increased immigration and higher fertility rates. The cities of Leipzig, Dresden and Chemnitz, and the towns of Radebeul and Markkleeberg in their vicinity, have seen their populations increase since 2000. The following tables illustrate the foreign resident populations and the population of Saxony since 1816:

| Significant foreign resident populations[13] | |

| Nationality | Population (31.12 2019) |

|---|---|

| 24,310 | |

| 18,730 | |

| 11,725 | |

| 11,620 | |

| 9,570 | |

| 8,435 | |

| 6,940 | |

| 6,795 | |

| 6,725 | |

| 6,575 | |

|

|

|

|

Birthrate

The average number of children per woman in Saxony was 1.60 in 2018, the fourth-highest rate of all German states.[14] Within Saxony, the highest is the Bautzen district with 1.77, while Leipzig is the lowest with 1.49. Dresden's fertility rate of 1.58 is the highest of all German cities with more than 500,000 inhabitants.

Sorbian population

Saxony is home to the Sorbs. There are currently between 45,000 and 60,000 Sorbs living in Saxony (Upper Lusatia region).[15][16] Today's Sorb minority is the remainder of the Slavic population that settled throughout Saxony in the early Middle Ages and over time slowly assimilated into the German speaking society. Many geographic names in Saxony are of Sorbic origin (including the three largest cities Chemnitz, Dresden and Leipzig). The Sorbic language and culture are protected by special laws and cities and villages in eastern Saxony that are inhabited by a significant number of Sorbian inhabitants have bilingual street signs and administrative offices provide service in both, German and Sorbian. The Sorbs enjoy cultural self-administration which is exercised through the Domowina. Former Minister President Stanislaw Tillich is of Sorbian ancestry and has been the first leader of a German state from a national minority.

Religion

As of 2011, the Evangelical Church in Germany represented the largest faith in the state, adhered to by 21.4% of the population. Members of the Roman Catholic Church formed a minority of 3.8%. About 0.9% of the Saxons belonged to an Evangelical free church (Evangelische Freikirche, i.e. various Protestants outside the EKD), 0.3% to Orthodox churches and 1% to other religious communities, while 72.6% did not belong to any public-law religious society.[17] The Moravian Church (see above) still maintains its religious centre in Herrnhut and it is there where 'The Daily Watchwords' (Losungen) are selected each year which are in use in many churches worldwide. In particular in the larger cities, there are numerous smaller religious communities. The international Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has a presence in the Freiberg Germany Temple which was the first of its kind in Germany, opened in 1985 even before its counterpart in Western Germany. It now also serves as a religious center for the church members in Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Hungary.[18] In Leipzig, there is a significant Buddhist community, which mainly caters to the population of Vietnamese origin, with one Buddhist temple built in 2008 and another one currently under construction.[19]

Economy

The Gross domestic product (GDP) of the state was 124.6 billion euros in 2018, accounting for 3.7% of German economic output. GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power was 28,100 euros or 93% of the EU27 average in the same year. The GDP per employee was 85% of the EU average. The GDP per capita was the highest of the states of the former GDR.[20] Saxony has a 'very high' Human Development Index value of 0.930 (2018), which is at the same level as Denmark.[2] Within Germany Saxony is ranked 9th.

Saxony has, after Saxony Anhalt,[21] the most vibrant economy of the states of the former East Germany (GDR). Its economy grew by 1.9% in 2010.[22] Nonetheless, unemployment remains above the German average. The eastern part of Germany, excluding Berlin, qualifies as an "Objective 1" development-region within the European Union, and was eligible to receive investment subsidies up to 30% until 2013. FutureSAX, a business plan competition and entrepreneurial support organisation, has been in operation since 2002.

Microchip-makers near Dresden have given the region the nickname "Silicon Saxony". The publishing and porcelain industries of the region are well known, although their contributions to the regional economy are no longer significant. Today, the automobile industry, machinery production, and services mainly contribute to the economic development of the region.

Saxony reported an average unemployment of 5.5% in 2019.[23]

| Year | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unemployment rate in % | 17.2 | 17.0 | 17.5 | 17.8 | 17.9 | 17.8 | 18.3 | 17.0 | 14.7 | 12.8 | 12.9 | 11.8 | 10.6 | 9.8 | 9.4 | 8.8 | 8.2 | 7.5 | 6.7 | 6.0 | 5.5 |

The Leipzig area, which until recently was among the regions with the highest unemployment rate, could benefit greatly from investments by Porsche and BMW. With the VW Phaeton factory in Dresden, and many parts suppliers, the automobile industry has again become one of the pillars of Saxon industry, as it was in the early 20th century. Zwickau is another major Volkswagen location. Freiberg, a former mining town, has emerged as a foremost location for solar technology. Dresden and some other regions of Saxony play a leading role in some areas of international biotechnology, such as electronic bioengineering. While these high-technology sectors do not yet offer a large number of jobs, they have stopped or even reversed the brain drain that was occurring until the early 2000s in many parts of Saxony. Regional universities have strengthened their positions by partnering with local industries. Unlike smaller towns, Dresden and Leipzig in the past experienced significant population growth.[24]

Dresden is the hub of Silicon Saxony.

Dresden is the hub of Silicon Saxony. Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk is one of Germany's public broadcasters.

Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk is one of Germany's public broadcasters. Leipzig/Halle Airport is the main hub of DHL and the fifth-busiest airport in Europe in terms of cargo traffic.

Leipzig/Halle Airport is the main hub of DHL and the fifth-busiest airport in Europe in terms of cargo traffic. VNG – Verbundnetz Gas in Leipzig is the third-largest natural-gas importer in Germany.

VNG – Verbundnetz Gas in Leipzig is the third-largest natural-gas importer in Germany. Porsche customer center in Leipzig

Porsche customer center in Leipzig BMW production facility in Leipzig

BMW production facility in Leipzig Bombardier Transportation in Bautzen

Bombardier Transportation in Bautzen

International trade

Saxony is a strongly export-oriented economy. In 2018, exports amounted to 40,48 billion euro while imports stood at 24,41 billion euro. The largest export partner of Saxony is China with an amount of 6,72 billion euro, while the second largest export market are the United States with 3.59 billion.[25] The largest exporting sectors are the automobile industry and mechanical engineering.

Tourism

Saxony is a renowned tourist destination in Germany. The cities of Dresden and Leipzig are two of Germany's most visited cities.[26] Areas along the border with the Czech Republic, such as the Lusatian Mountains, Ore Mountains, Saxon Switzerland, and Vogtland, attract significant numbers of visitors. In addition, Saxony has well-preserved historic towns such as Görlitz, Bautzen, Freiberg, Pirna, Meissen and Stolpen as well as numerous castles and palaces. New tourist destinations are developing, notably in the Lusatian Lake District.[27]

Dresden is one of the most visited cities in Germany and Europe.

Dresden is one of the most visited cities in Germany and Europe. The Dresden Frauenkirche. It now serves as a symbol of reconciliation between former warring enemies.

The Dresden Frauenkirche. It now serves as a symbol of reconciliation between former warring enemies. Leipziger Neuseenland is a large lake district south of Leipzig, one of Germany's most vibrant cities.

Leipziger Neuseenland is a large lake district south of Leipzig, one of Germany's most vibrant cities..jpg) The Bastei bridge in Saxon Switzerland

The Bastei bridge in Saxon Switzerland- The Rakotz bridge at Azalea and Rhododendron Park Kromlau

The historical city of Görlitz

The historical city of Görlitz The Elbe valley with Meissen in the background

The Elbe valley with Meissen in the background.jpeg) Saxony is home to numerous castles, such as Schloss Moritzburg north of Dresden.

Saxony is home to numerous castles, such as Schloss Moritzburg north of Dresden.

Education

Saxony's school system belongs to the most excelling ones in Germany. It has been ranked first in the German school assessment (Bildungsmonitor) for several years.[28]

Saxony has four large universities and five Fachhochschulen or Universities of Applied Sciences. The Dresden University of Technology (TU Dresden), founded in 1828, is one of Germany's oldest universities. With 36,066 students as of 2010, it is the largest university in Saxony and one of the ten largest universities in Germany. It is a member of TU9, a consortium of nine leading German Institutes of Technology.

Leipzig University is one of the oldest universities in the world and the second-oldest university (by consecutive years of existence) in Germany, founded in 1409. Famous alumni include Leibniz, Goethe, Ranke, Nietzsche, Wagner, Cai Yuanpei, Angela Merkel, Raila Odinga, Tycho Brahe, and nine Nobel laureates are associated with this university.

Saxony is home to several Max Planck Institutes.

One of the two main campuses of the German National Library is located in Leipzig.

Culture

Saxony is part of 'Central Germany' as a cultural area. As such, throughout German history it played an important role in shaping German culture.

Languages

The most common patois spoken in Saxony are combined in the group of "Thuringian and Upper Saxon dialects". Due to the inexact use of the term "Saxon dialects" in colloquial language, the Upper Saxon attribute has been added to distinguish it from Old Saxon and Low Saxon. Other German dialects spoken in Saxony are the dialects of the Erzgebirge (Ore Mountains), which have been affected by Upper Saxon dialects, and the dialects of the Vogtland, which are more affected by the East Franconian languages.

Upper Sorbian (a West Slavic language) is spoken in the parts of Upper Lusatia that are inhabited by the Sorbian minority. The Germans in Upper Lusatia speak distinct dialects of their own (Lusatian dialects).

Sports

The most popular sport in Saxony is football. With RB Leipzig there is one Saxon team playing in the Bundesliga as well as the European Champions League. Leipzig is notable for a longstanding football tradition, a Leipzig team having been the first national football champion in German history. Another popular sport is handball with several Bundesliga teams from Saxony. On a local level such sports as table tennis, cycling, mountaineering and volleyball are popular. In 2020, there were 4.447 registered sports clubs of various disciplines with over 600.000 members in Saxony.[29]

Motherland of the Reformation

Saxony is often seen as the motherland of the Reformation.[30] It was predominantly Lutheran Protestant from the Reformation until the late 20th century.

The Electoral Saxony, a predecessor of today's Saxony, was the original birthplace of the Reformation. The elector was Lutheran starting in 1525. The Lutheran church was organized through the late 1510s and the early 1520s. It was officially established in 1527 by John the Steadfast. Although some of the sites associated with Martin Luther also lie in the current state of Saxony-Anhalt (including Wittenberg, Eisleben and Mansfeld), today's Saxony is usually viewed as the formal successor to what used to be Luther's country back in the 16th century (i.e. the Electoral Saxony).

Martin Luther personally oversaw the Lutheran church in Saxony and shaped it consistently with his own views and ideas. The 16th, 17th and 18th centuries were heavily dominated by Lutheran orthodoxy. In addition, the Reformed faith made inroads with the so-called crypto Calvinists, but was strongly persecuted in an overwhelmingly Lutheran state. In the 17th century, Pietism became an important influence. In the 18th century, the Moravian Church was set up on Count von Zinzendorf's property at Herrnhut. From 1525, the rulers were traditionally Lutheran and widely acknowledged as defenders of the Protestant faith, although – beginning with Augustus II the Strong, who was required to convert to Roman Catholicism in 1697 in order to become King of Poland – its monarchs were exclusively Roman Catholic. That meant Augustus and the subsequent Electors of Saxony, who were Roman Catholic, ruled over a state with an almost entirely Protestant population.

In 1925, 90.3% of the Saxon population was Protestant, 3.6% was Roman Catholic, 0.4% was Jewish and 5.7% was placed in other religious categories.[31]

After World War II, Saxony was incorporated into East Germany which pursued a policy of state atheism. After 45 years of Communist rule, the majority of the population has become unaffiliated. Nonetheless, even during this time Saxony remained an important place of religious dialogue and it was at Meissen where the agreement on mutual recognition between the German Evangelical Church and the Church of England was signed in 1988.[32]

Cuisine

Saxon cuisine encompasses regional cooking traditions of Saxony. In general the cuisine is very hearty and features many peculiarities of Mid-Germany such as a great variety of sauces which accompany the main dish and the fashion to serve potatoe dumplings (Klöße/Knödel) as a side dish instead of potatoes, pasta or rice. Also much freshwater fish is used in Saxon cuisine. The area around Dresden is home to the easternmost wine region in Germany (see: Saxony (wine region)).

Art

The two major cultural centers of Saxony are Dresden and Leipzig. The two cities have each a unique character which is reflecting the role they played throughout Saxon and German history, Dresden being a political center while Leipzig has been a major trading city. Thus, Dresden is well known for the art collections of the former Saxon kings (Green Vault, Zwinger).

Leipzig on the other hand never had a royal court, so its culture is borne largely by its citizens. The city is famous for its relationship with classical music and names like Johann Sebastian Bach, Mendelssohn or Wagner are linked to it. Over the past decades the city became famous for its modern art szene, most notably the Leipzig School (Neue Leipziger Schule).

Porcelain

Saxony was the first place in Europe to develop and produce white porcelain, a luxury good until than imported only from China. The Meissen Porcelain Manufactory exists until today.

Rock Climbing

Saxony prides itself to have been one of the first places in the world where modern recreational rock climbing was developed. Falkenstein rock in the area of Bad Schandau is considered to be the place were the German rock climbing tradition started in 1864.

Anthem

Saxony (as other German states) has its own anthem, dating back to the monarchy of the 19th century. 'Gott segne Sachsenland' (God save Saxony) is based on the melody of God save the queen.

See also

References

- "Bruttoinlandsprodukt – in jeweiligen Preisen – 1991 bis 2019". statistik-bw.de.

- "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- The Ascanian coat-of-arms shows the Ascanian barry of ten, in sable and or, covered by a crancelin of rhombs bendwise in vert.

- Pollock & Thomas (1952), p. 486

- Pollock & Thomas (1952), p. 510

- Pollock & Thomas (1952), pp. 510–511

- Pollock & Thomas (1952), p. 511

- "Bevölkerung des Freistaates Sachsen jeweils am Monatsende ausgewählter Berichtsmonate nach Gemeinden" (PDF). Statistik.sachsen.de. 30 September 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- Stadtplan.net. "Ballungsraum Leipzig/Halle". Stadtplan.net. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- eCommerce, Deutsche Bahn AG, Unternehmensbereich Personenverkehr, Marketing. "S-Bahn Mitteldeutschland". S-bahn-mitteldeutschland.de. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- "Flughafen Leipzig/Halle - Passengers and visitors > Flights > Flights". Leipzig-halle-airport.de. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- "Zensus 2014: Bevölkerung" (PDF). German Statistical Office. 31 December 2014.

- "Gestiegene Geburtenhäufigkeit bei älteren Müttern". Destatis. 3 September 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Jana Šołćina, Edward Wornar: Obersorbisch im Selbststudium, Hornjoserbšćina za samostudij. Bautzen: Domowina-Verlag, 2000. Page 10.

- Gebel, K. (2002). Language and ethnic national identity in Europe: the importance of Gaelic and Sorbian to the maintenance of associated cultures and ethno cultural identities (PDF). London: Middlesex University.

- "Zensusdatenbank". Ergebnisse.zensus2011.de.

- Taylor, Scott (6 September 2010). "Non-Mormons call Freiberg Germany LDS temple their own". Deseret News. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- https://www.sachsen-fernsehen.de/hier-entsteht-der-groesste-buddhistische-tempel-sachsens-410220/

- "Regional GDP per capita ranged from 30% to 263% of the EU average in 2018". Eurostat.

- "Die Arbeitsmarkt im Juli 2014" (PDF). IHK Berlin. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- Freistaat Sachsen - Die angeforderte Seite existiert leider nicht Archived 30 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Smwa.sachsen.de. Retrieved on 2013-07-16.

- "Arbeitslosenquote* in Sachsen von 1999 bis 2019". Statista. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- "Arbeitslosenquote in Deutschland nach Bundesländern 2013". De.statista.com. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- title=Saechsisches Landesamt fuer Statistik (Saxon Statistics Authority)|website=https://standort-sachsen.de/de/exporteure/sachsens-aussenhandel%7Caccessdate=7 June 2019

- Zahlen Daten Fakten 2012 (in German), German National Tourist Board

- "Still Troubled". The Economist. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- https://www.schule.sachsen.de/6622.htm

- https://www.sport-fuer-sachsen.de/de/presse/pressemitteilungen/?tx_ifabprins_pressmanagement%5Bid%5D=654&tx_ifabprins_pressmanagement%5Baction%5D=show&tx_ifabprins_pressmanagement%5Bcontroller%5D=PressManagement&cHash=0cd8f0d3dda23366d10ae368459b0d50

- "Motherland of the Reformation". sachsen-tourismus.de. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Grundriss der Statistik. II. Gesellschaftsstatistik by Wilhelm Winkler, p. 36

- https://www.churchofengland.org/media/3320&ved=2ahUKEwjUh6uiztfpAhWKFMAKHbW8DpYQFjACegQIBRAC&usg=AOvVaw1xmR136YlRRPfMCxfjH_cG

Bibliography

- Pollock, James K.; Thomas, Homer (1952). Germany in Power and Eclipse. New York, NY: D. Van Nostrand.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Saxony. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Saxony. |

- Official governmental portal