Aachen

Aachen (/ˈɑːxən/,[2][3] German: [ˈʔaːxn̩] (![]()

Aachen | |

|---|---|

Panoramic view of Aachen, including Kaiser-Karls-Gymnasium (foreground), city hall (back centre) and cathedral (back right) | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

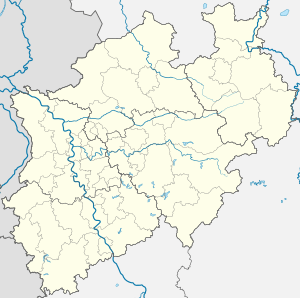

Location of Aachen within Aachen district .svg.png) | |

Aachen  Aachen | |

| Coordinates: 50°46′32″N 06°05′01″E | |

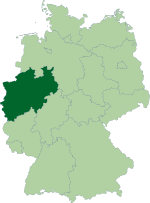

| Country | Germany |

| State | North Rhine-Westphalia |

| Admin. region | Cologne |

| District | Aachen |

| Government | |

| • Lord Mayor | Marcel Philipp (CDU) |

| • Governing parties | CDU / SPD |

| Area | |

| • Total | 160.85 km2 (62.10 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 173 m (568 ft) |

| Population (2018-12-31)[1] | |

| • Total | 247,380 |

| • Density | 1,500/km2 (4,000/sq mi) |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) |

| Postal codes | 52062–52080 |

| Dialling codes | 0241 / 02405 / 02407 / 02408 |

| Vehicle registration | AC / MON |

| Website | aachen |

Aachen is the westernmost city in Germany, located near the borders with Belgium and the Netherlands, 61 km (38 mi) west of Cologne[8][9] in a former coal-mining area.[9] One of Germany's leading institutes of higher education in technology, the RWTH Aachen University, is located in the city.[lower-alpha 2][10] Aachen's industries include science, engineering and information technology. In 2009, Aachen was ranked eighth among cities in Germany for innovation.[11]

Name

The name Aachen is a modern descendant, like southern German Ach(e), German: Aach, meaning "river" or "stream", from Old High German ahha, meaning "water" or "stream", which directly translates (and etymologically corresponds) to Latin Aquae, referring to the springs. The location has been inhabited by humans since the Neolithic era, about 5,000 years ago, attracted to its warm mineral springs. Latin Aquae figures in Aachen's Roman name Aquae granni, which meant "waters of Grannus", referring to the Celtic god of healing who was worshipped at the springs.[7][12] This word became Åxhe in Walloon and Aix in French, and subsequently Aix-la-Chapelle after Charlemagne had his palatine chapel built there in the late 8th century and then made the city his empire's capital.

As a spa city, Aachen has the right to name itself Bad Aachen, but chooses not to, so it remains on the top of alphabetical lists.

Aachen's name in French and German evolved in parallel. The city is known by a variety of different names in other languages:

| Language | Name | Pronunciation in IPA |

|---|---|---|

| Aachen dialect | Oche | [ˈɔːxə] |

| Catalan | Aquisgrà | [əkizˈɡɾa] |

| Czech | Cáchy | [ˈtsaːxɪ] |

| Dutch / Low German | Aken[13] | [ˈaːkə(n)] ( |

| French | Aix-la-Chapelle[13] | [ɛks la ʃapɛl] |

| Greek | Ἀκυΐσγρανον (Akyísgranon) | [aciˈizɣranon] |

| Italian | Aquisgrana | [akwizˈɡraːna] |

| Latin | Aquisgrana[14] Aquae granni[7] Aquis Granum[15] | |

| Limburgish | Aoke | [ˈɒ̀ːkə] |

| Luxembourgish | Oochen | [ˈoːχən] |

| Polish | Akwizgran | [aˈkfizɡran] |

| Portuguese | Aquisgrano, Aquisgrão | [ɐkiʒˈɡɾɐnu], [ɐkiʒˈɡɾɐ̃w̃] |

| Spanish | Aquisgrán[13] | [akizˈɣɾan] |

| Walloon | Åxhe | [ɑːç] |

Aachen dialect

Aachen is at the western end of the Benrath line that divides High German to the south from the rest of the West Germanic speech area to the north.[16] Aachen's local dialect is called Öcher Platt and belongs to the Ripuarian language.

History

Early history

Flint quarries on the Lousberg, Schneeberg, and Königshügel, first used during Neolithic times (3000–2500 BC), attest to the long occupation of the site of Aachen, as do recent finds under the modern city's Elisengarten pointing to a former settlement from the same period. Bronze Age (around 1600 BC) settlement is evidenced by the remains of barrows (burial mounds) found, for example, on the Klausberg. During the Iron Age, the area was settled by Celtic peoples[17] who were perhaps drawn by the marshy Aachen basin's hot sulphur springs where they worshipped Grannus, god of light and healing.

Later, the 25-hectare Roman spa resort town of Aquae Granni was, according to legend, founded by Grenus, under Hadrian, around 124 AD. Instead, the fictitious founder refers to the Celtic god, and it seems it was the Roman 6th Legion at the start of the 1st century AD that first channelled the hot springs into a spa at Büchel,[8][lower-alpha 3] adding at the end of the same century the Münstertherme spa,[18] two water pipelines, and a probable sanctuary dedicated to Grannus. A kind of forum, surrounded by colonnades, connected the two spa complexes. There was also an extensive residential area, part of it inhabited by a flourishing Jewish community.[19] The Romans built bathhouses near Burtscheid. A temple precinct called Vernenum was built near the modern Kornelimünster/Walheim. Today, remains have been found of three bathhouses,[20] including two fountains in the Elisenbrunnen and the Burtscheid bathhouse.

Roman civil administration in Aachen broke down between the end of the 4th and beginning of the 5th centuries. Rome withdrew its troops from the area, but the town remained populated. By 470, the town came to be ruled by the Ripuarian Franks[21] and subordinated to their capital, Cologne.

Middle Ages

After Roman times, Pepin the Short had a castle residence built in the town, due to the proximity of the hot springs and also for strategic reasons as it is located between the Rhineland and northern France.[22] Einhard mentions that in 765–6 Pepin spent both Christmas and Easter at Aquis villa (Et celebravit natalem Domini in Aquis villa et pascha similiter.),[23] ("and [he] celebrated Christmas in the town Aquis, and similarly Easter") which must have been sufficiently equipped to support the royal household for several months. In the year of his coronation as king of the Franks, 768, Charlemagne came to spend Christmas at Aachen for the first time.[lower-alpha 4] He remained there in a mansion which he may have extended, although there is no source attesting to any significant building activity at Aachen in his time, apart from the building of the Palatine Chapel (since 1930, cathedral) and the Palace. Charlemagne spent most winters in Aachen between 792 and his death in 814. Aachen became the focus of his court and the political centre of his empire. After his death, the king was buried in the church which he had built;[25] his original tomb has been lost, while his alleged remains are preserved in the Karlsschrein, the shrine where he was reburied after being declared a saint; his saintliness, however, was never officially acknowledged by the Roman Curia as such.

In 936, Otto I was crowned king of East Francia in the collegiate church built by Charlemagne. During the reign of Otto II, the nobles revolted and the West Franks, under Lothair,[26] raided Aachen in the ensuing confusion.[27][lower-alpha 5] Aachen was attacked again by Odo of Champagne, who attacked the imperial palace while Conrad II was absent. Odo relinquished it quickly and was killed soon afterwards.[28] The palace and town of Aachen had fortifying walls built by order of Emperor Frederick Barbarossa between 1172 and 1176.[20] Over the next 500 years, most kings of Germany destined to reign over the Holy Roman Empire were crowned in Aachen. The original audience hall built by Charlemagne was torn down and replaced by the current city hall in 1330.[lower-alpha 6][20] The last king to be crowned here was Ferdinand I in 1531.[8][29] During the Middle Ages, Aachen remained a city of regional importance, due to its proximity to Flanders; it achieved a modest position in the trade in woollen cloths, favoured by imperial privilege. The city remained a free imperial city, subject to the emperor only, but was politically far too weak to influence the policies of any of its neighbours. The only dominion it had was over Burtscheid, a neighbouring territory ruled by a Benedictine abbess. It was forced to accept that all of its traffic must pass through the "Aachener Reich". Even in the late 18th century the Abbess of Burtscheid was prevented from building a road linking her territory to the neighbouring estates of the duke of Jülich; the city of Aachen even deployed its handful of soldiers to chase away the road-diggers.

As an imperial city, Aachen held certain political privileges that allowed it to remain independent of the troubles of Europe for many years. It remained a direct vassal of the Holy Roman Empire throughout most of the Middle Ages. It was also the site of many important church councils, including the Council of 837[30] and the Council of 1166, a council convened by the antipope Paschal III.[9]

Manuscript production

Aachen has proved an important site for the production of historical manuscripts. Under Charlemagne's purview, both the Ada Gospels and the Coronation Gospels may have been produced in Aachen.[31] In addition, quantities of the other texts in the court library were also produced locally. During the reign of Louis the Pious (814–840), substantial quantities of ancient texts were produced at Aachen, including legal manuscripts such as the leges scriptorium group, patristic texts including the five manuscripts of the Bamberg Pliny Group.[31] Finally, under Lothair I (840–855), texts of outstanding quality were still being produced. This however marked the end of the period of manuscript production at Aachen.[31]

16th–18th centuries

In 1598, following the invasion of Spanish troops from the Netherlands, Rudolf deposed all Protestant office holders in Aachen and even went as far as expelling them from the city.[32] From the early 16th century, Aachen started to lose its power and influence. First the coronations of emperors were moved from Aachen to Frankfurt. This was followed by the religious wars, and the great fire of 1656.[33] After the destruction of most of the city in 1656, the rebuilding was mostly in the Baroque style.[20] The decline of Aachen culminated in 1794, when the French, led by General Charles Dumouriez,[21] occupied Aachen.[29]

In 1542, the Dutch humanist and physician Francis Fabricius published his study of the health benefits of the hot springs in Aachen,[34] and by the middle of the 17th century the city had developed a considerable reputation as a spa, although this was in part because Aachen was then – and remained well into the 19th century – a place of high-level prostitution. Traces of this hidden agenda of the city's history are found in the 18th-century guidebooks to Aachen as well as to the other spas.

The main indication for visiting patients, ironically, was syphilis; only by the end of the 19th century had rheumatism become the most important object of cures at Aachen and Burtscheid.

Aachen was chosen as the site of several important congresses and peace treaties: the first congress of Aachen (often referred to as the Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle in English) on 2 May 1668,[35] leading to the First Treaty of Aachen in the same year which ended the War of Devolution.[36] The second congress ended with the second treaty in 1748, ending the War of the Austrian Succession.[8][37] In 1789, there was a constitutional crisis in the Aachen government,[38] and in 1794 Aachen lost its status as a free imperial city.[20]

19th century

On 9 February 1801, the Peace of Lunéville removed the ownership of Aachen and the entire "left bank" of the Rhine from Germany (the Holy Roman Empire) and granted it to France.[21] In 1815, control of the town was passed to the Kingdom of Prussia through an act passed by the Congress of Vienna.[20][29] The third congress took place in 1818, to decide the fate of occupied Napoleonic France.

By the middle of the 19th century, industrialisation had swept away most of the city's medieval rules of production and commerce, although the entirely corrupt remains of the city's medieval constitution were kept in place (compare the famous remarks of Georg Forster in his Ansichten vom Niederrhein) until 1801, when Aachen became the "chef-lieu du département de la Roer" in Napoleon's First French Empire. In 1815, after the Napoleonic Wars, the Kingdom of Prussia took over within the new German Confederation. The city was one of its most socially and politically backward centres until the end of the 19th century.[8] Administered within the Rhine Province, by 1880 the population was 80,000. Starting in 1838, the railway from Cologne to Belgium passed through Aachen.[39] The city suffered extreme overcrowding and deplorable sanitary conditions until 1875, when the medieval fortifications were finally abandoned as a limit to building and new, better housing was built in the east of the city, where sanitary drainage was easiest. In December 1880, the Aachen tramway network was opened, and in 1895 it was electrified.[40] In the 19th century and up to the 1930s, the city was important in the production of railway locomotives and carriages, iron, pins, needles, buttons, tobacco, woollen goods, and silk goods.

20th century

World War II

After World War I, Aachen was occupied by the Allies until 1930, along with the rest of German territory west of the Rhine.[29] Aachen was one of the locations involved in the ill-fated Rhenish Republic. On 21 October 1923, an armed mob took over the city hall. Similar actions took place in Mönchen-Gladbach, Duisburg, and Krefeld. This republic lasted only about a year.[41] Aachen was heavily damaged during World War II. According to Jörg Friedrich in The Fire (2008), two Allied air raids on 11 April and 24 May 1944 "radically destroyed" the city. The first killed 1,525, including 212 children, and bombed six hospitals. During the second, 442 aircraft hit two railway stations, killed 207, and left 15,000 homeless. The raids also destroyed Aachen-Eilendorf and Aachen-Burtscheid.[42]

The city and its fortified surroundings were laid siege to from 12 September to 21 October 1944 by the US 1st Infantry Division[43] with the 3rd Armored Division assisting from the south.[44] Around 13 October the US 2nd Armored Division played their part, coming from the north and getting as close as Würselen,[45] while the 30th Infantry Division played a crucial role in completing the encirclement of Aachen on 16 October 1944.[46] With reinforcements from the US 28th Infantry Division[47] the Battle of Aachen then continued involving direct assaults through the heavily defended city, which finally forced the German garrison to surrender on 21 October 1944.[43]

Aachen was the first German city to be captured by the Allies, and its residents welcomed the soldiers as liberators.[48] What remained of the city was destroyed—in some areas completely—during the fighting,[8] mostly by American artillery fire and demolitions carried out by the Waffen-SS defenders. Damaged buildings included the medieval churches of St. Foillan, St. Paul and St. Nicholas, and the Rathaus (city hall), although Aachen Cathedral was largely unscathed. Only 4,000 inhabitants remained in the city; the rest had followed evacuation orders. Its first Allied-appointed mayor, Franz Oppenhoff, was assassinated by an SS commando unit.

History of Aachen Jews

During the Roman period, Aachen was the site of a flourishing Jewish community. Later, during the Carolingian empire, a Jewish community lived near the royal palace.[19] In 797, Isaac, a Jewish merchant, accompanied two ambassadors of Charlemagne to the court of Harun al-Rashid. He returned to Aachen in July 802, bearing an elephant called Abul-Abbas as a gift for the emperor.[49] During the 13th century, many Jews converted to Christianity, as shown in the records of the Aachen Minster (today's Cathedral). In 1486, the Jews of Aachen offered gifts to Maximilian I during his coronation ceremony. In 1629, the Aachen Jewish community was expelled from the city. In 1667, six Jews were allowed to return. Most of the Aachen Jews settled in the nearby town of Burtscheid. On 16 May 1815, the Jewish community of the city offered an homage in its synagogue to the Prussian king, Friedrich Wilhelm III. A Jewish cemetery was acquired in 1851. 1,345 Jews lived in the city in 1933. The synagogue was destroyed during Kristallnacht in 1938. In 1939, after emigration and arrests, 782 Jews remained in the city. After World War II, only 62 Jews lived there. In 2003, 1,434 Jews were living in Aachen. In Jewish texts, the city of Aachen was called Aish or Ash (אש).

21st century

The city of Aachen has developed into a technology hub as a by-product of hosting one of the leading universities of technology in Germany with the RWTH Aachen (Rheinisch-Westfälische Technische Hochschule), known especially for mechanical engineering, automotive and manufacturing technology as well as for its research and academic hospital Klinikum Aachen, one of the largest medical facilities in Europe.

Geography

Aachen is located in the middle of the Meuse–Rhine Euroregion, close to the border tripoint of Germany, the Netherlands, and Belgium. The town of Vaals in the Netherlands lies nearby at about 6 km (4 mi) from Aachen's city centre, while the Dutch city of Heerlen and Eupen, the capital of the German-speaking Community of Belgium, are both located about 20 km (12 mi) from Aachen city centre. Aachen lies near the head of the open valley of the Wurm (which today flows through the city in canalised form), part of the larger basin of the Meuse, and about 30 km (19 mi) north of the High Fens, which form the northern edge of the Eifel uplands of the Rhenish Massif.

The maximum dimensions of the city's territory are 21.6 km (13 3⁄8 mi) from north to south, and 17.2 km (10 3⁄4 mi) from east to west. The city limits are 87.7 km (54 1⁄2 mi) long, of which 23.8 km (14 3⁄4 mi) border Belgium and 21.8 km (13 1⁄2 mi) the Netherlands. The highest point in Aachen, located in the far southeast of the city, lies at an elevation of 410 m (1,350 ft) above sea level. The lowest point, in the north, and on the border with the Netherlands, is at 125 m (410 ft).

Climate

As the westernmost city in Germany[7] (and close to the Low Countries), Aachen and the surrounding area belongs to a temperate climate zone, with humid weather, mild winters, and warm summers. Because of its location north of the Eifel and the High Fens and its subsequent prevailing westerly weather patterns, rainfall in Aachen (on average 805 mm/year) is comparatively higher than, for example, in Bonn (with 669 mm/year). Another factor in the local weather forces of Aachen is the occurrence of Foehn winds on the southerly air currents, which results from the city's geographic location on the northern edge of the Eifel.[50]

Because the city is surrounded by hills, it suffers from inversion-related smog. Some areas of the city have become urban heat islands as a result of poor heat exchange, both because of the area's natural geography and from human activity. The city's numerous cold air corridors, which are slated to remain as free as possible from new construction, therefore play an important role in the urban climate of Aachen.[51]

The January average is 3.0 °C (37 °F), while the July average is 18.5 °C (65 °F). Precipitation is almost evenly spread throughout the year.

| Climate data for Aachen, Germany for 1981–2010 (Source: DWD) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.2 (61.2) |

20.2 (68.4) |

23.1 (73.6) |

28.7 (83.7) |

32.8 (91.0) |

34.5 (94.1) |

36.7 (98.1) |

36.8 (98.2) |

32.2 (90.0) |

26.9 (80.4) |

22.1 (71.8) |

16.8 (62.2) |

36.8 (98.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 5.4 (41.7) |

6.2 (43.2) |

10.1 (50.2) |

14.1 (57.4) |

18.2 (64.8) |

20.8 (69.4) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.0 (73.4) |

19.2 (66.6) |

14.8 (58.6) |

9.3 (48.7) |

5.9 (42.6) |

14.2 (57.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 3.0 (37.4) |

3.2 (37.8) |

6.4 (43.5) |

9.5 (49.1) |

13.6 (56.5) |

16.2 (61.2) |

18.5 (65.3) |

18.0 (64.4) |

14.6 (58.3) |

11.0 (51.8) |

6.6 (43.9) |

3.7 (38.7) |

10.4 (50.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 0.7 (33.3) |

0.6 (33.1) |

3.2 (37.8) |

5.5 (41.9) |

9.2 (48.6) |

11.8 (53.2) |

14.1 (57.4) |

13.9 (57.0) |

11.2 (52.2) |

7.9 (46.2) |

4.3 (39.7) |

1.5 (34.7) |

7.0 (44.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −16.4 (2.5) |

−15.8 (3.6) |

−9.9 (14.2) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

0.4 (32.7) |

3.9 (39.0) |

5.8 (42.4) |

6.7 (44.1) |

3.8 (38.8) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

−7.6 (18.3) |

−14.3 (6.3) |

−16.4 (2.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 68.1 (2.68) |

63.6 (2.50) |

67.0 (2.64) |

55.7 (2.19) |

72.0 (2.83) |

80.3 (3.16) |

75.2 (2.96) |

74.8 (2.94) |

69.2 (2.72) |

70.1 (2.76) |

66.1 (2.60) |

74.9 (2.95) |

836.8 (32.94) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 63.5 | 83.0 | 119.3 | 163.4 | 195.6 | 196.6 | 208.5 | 195.7 | 149.3 | 120.4 | 71.0 | 50.2 | 1,616.5 |

| Source: Data derived from Deutscher Wetterdienst[52] | |||||||||||||

Geology

The geology of Aachen is very structurally heterogeneous. The oldest occurring rocks in the area surrounding the city originate from the Devonian period and include carboniferous sandstone, greywacke, claystone and limestone. These formations are part of the Rhenish Massif, north of the High Fens. In the Pennsylvanian subperiod of the Carboniferous geological period, these rock layers were narrowed and folded as a result of the Variscan orogeny. After this event, and over the course of the following 200 million years, this area has been continuously flattened.[53]

During the Cretaceous period, the ocean penetrated the continent from the direction of the North Sea up to the mountainous area near Aachen, bringing with it clay, sand, and chalk deposits. While the clay (which was the basis for a major pottery industry in nearby Raeren) is mostly found in the lower areas of Aachen, the hills of the Aachen Forest and the Lousberg were formed from upper Cretaceous sand and chalk deposits. More recent sedimentation is mainly located in the north and east of Aachen and was formed through tertiary and quaternary river and wind activities.

Along the major thrust fault of the Variscan orogeny, there are over 30 thermal springs in Aachen and Burtscheid. Additionally, the subsurface of Aachen is traversed by numerous active faults that belong to the Rurgraben fault system, which has been responsible for numerous earthquakes in the past, including the 1756 Düren earthquake[54] and the 1992 Roermond earthquake,[55] which was the strongest earthquake ever recorded in the Netherlands.

Demographics

Aachen has 245,885 inhabitants (as of 31 December 2015), of whom 118,272 are female, and 127,613 are male.[56]

The unemployment rate in the city is, as of April 2012, 9.7 percent.[57] At the end of 2009, the foreign-born residents of Aachen made up 13.6 percent of the total population.[58] A significant portion of foreign residents are students at the RWTH Aachen University.[59]

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1994 | 246,570[60] |

| 2007 | 247,740[24] |

| 2011 | 238,665[56] |

| 2014 | 243,336[56] |

| 2015 | 245,885[56] |

| Largest groups of foreign residents | |

|---|---|

| Nationality | Population (2019)[61] |

| 6,140 | |

| 3,225 | |

| 3,091 | |

| 1,925 | |

| 1,879 | |

| 1,836 | |

| 1,581 | |

| 1,543 | |

Boroughs

The city is divided into seven administrative districts, or boroughs, each with its own district council, district leader, and district authority. The councils are elected locally by those who live within the district, and these districts are further subdivided into smaller sections for statistical purposes, with each sub-district named by a two-digit number.

The districts of Aachen, including their constituent statistical districts, are:

- Aachen-Mitte: 10 Markt, 13 Theater, 14 Lindenplatz, 15 St. Jakob, 16 Westpark, 17 Hanbruch, 18 Hörn, 21 Ponttor, 22 Hansemannplatz, 23 Soers, 24 Jülicher Straße, 25 Kalkofen, 31 Kaiserplatz, 32 Adalbertsteinweg, 33 Panneschopp, 34 Rothe Erde, 35 Trierer Straße, 36 Frankenberg, 37 Forst, 41 Beverau, 42 Burtscheid Kurgarten, 43 Burtscheid Abbey, 46 Burtscheid Steinebrück, 47 Marschiertor, 48 Hangeweiher

- Brand: 51 Brand

- Eilendorf: 52 Eilendorf

- Haaren: 53 Haaren (including Verlautenheide)

- Kornelimünster/Walheim: 61 Kornelimünster, 62 Oberforstbach, 63 Walheim

- Laurensberg: 64 Vaalserquartier, 65 Laurensberg

- Richterich: 88 Richterich

Regardless of official statistical designations, there are 50 neighbourhoods and communities within Aachen, here arranged by district:

- Aachen-Mitte: Beverau, Bildchen, Burtscheid, Forst, Frankenberg, Grüne Eiche, Hörn, Lintert, Pontviertel, Preuswald, Ronheide, Rosviertel, Rothe Erde, Stadtmitte, Steinebrück, West

- Brand: Brand, Eich, Freund, Hitfeld, Niederforstbach

- Eilendorf: Eilendorf, Nirm

- Haaren: Haaren, Hüls, Verlautenheide

- Kornelimünster/Walheim: Friesenrath, Hahn, Kitzenhaus, Kornelimünster, Krauthausen, Lichtenbusch, Nütheim, Oberforstbach, Sief, Schleckheim, Schmithof, Walheim

- Laurensberg: Gut Kullen, Kronenberg, Laurensberg, Lemiers, Melaten, Orsbach, Seffent, Soers, Steppenberg, Vaalserquartier, Vetschau

- Richterich: Horbach, Huf, Richterich

Neighbouring communities

The following cities and communities border Aachen, clockwise from the northwest: Herzogenrath, Würselen, Eschweiler, Stolberg and Roetgen (which are all in the district of Aachen); Raeren, Kelmis and Plombières (Lüttich Province in Belgium) as well as Vaals, Gulpen-Wittem, Simpelveld, Heerlen and Kerkrade (all in Limburg Province in the Netherlands).

Main sights

Aachen Cathedral

Aachen Cathedral was erected on the orders of Charlemagne. Construction began c. AD 796[9] and it was, on completion c. 798,[62] the largest cathedral north of the Alps. It was modelled after the Basilica of San Vitale, in Ravenna, Italy,[29] and was built by Odo of Metz.[9] Charlemagne also desired for the chapel to compete with the Lateran Palace, both in quality and authority.[63] It was originally built in the Carolingian style, including marble covered walls, and mosaic inlay on the dome.[64] On his death, Charlemagne's remains were interred in the cathedral and can be seen there to this day. The cathedral was extended several times in later ages, turning it into a curious and unique mixture of building styles. The throne and gallery portion date from the Ottonian, with portions of the original opus sectile floor still visible.[64] The 13th century saw gables being added to the roof, and after the fire of 1656, the dome was rebuilt. Finally, a choir was added around the start of the 15th century.[25]

After Frederick Barbarossa canonised Charlemagne in 1165 the chapel became a destination for pilgrims.[25] For 600 years, from 936 to 1531, Aachen Cathedral was the church of coronation for 30 German kings and 12 queens. The church built by Charlemagne is still the main attraction of the city.[65] In addition to holding the remains of its founder, it became the burial place of his successor Otto III. In the upper chamber of the gallery, Charlemagne's marble throne is housed.[66] Aachen Cathedral has been designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[67]

Most of the marble and columns used in the construction of the cathedral were brought from Rome and Ravenna, including the sarcophagus in which Charlemagne was eventually laid to rest.[63] A bronze bear from Gaul was placed inside, along with an equestrian statue from Ravenna, believed to be Theodric, in contrast to a wolf and a statue of Marcus Aurelius in the Capitoline.[63] Bronze pieces such as the doors and railings, some of which have survived to present day, were cast in a local foundry. Finally, there is uncertainty surrounding the bronze pine cone in the chapel, and where it was created. Wherever it was made, it was also a parallel to a piece in Rome, this in Old St. Peter's Basilica.[63]

Cathedral Treasury

Aachen Cathedral Treasury has housed, throughout its history, a collection of liturgical objects. The origin of this church treasure is in dispute as some say Charlemagne himself endowed his chapel with the original collection, while the rest were collected over time. Others say all of the objects were collected over time, from such places as Jerusalem and Constantinople.[63] The location of this treasury has moved over time and was unknown until the 15th century when it was located in the Matthiaskapelle (St. Matthew's Chapel) until 1873, when it was moved to the Karlskapelle (Charles' Chapel). From there it was moved to the Hungarian Chapel in 1881 and in 1931 to its present location next to the Allerseelenkapelle (Poor Souls' Chapel).[63] Only six of the original Carolingian objects have remained, and of those only three are left in Aachen: the Aachen Gospels, a diptych of Christ, and an early Byzantine silk. The Coronation Gospels and a reliquary burse of St. Stephen were moved to Vienna in 1798 and the Talisman of Charlemagne was given as a gift in 1804 to Josephine Bonaparte and subsequently to Rheims Cathedral.[63] 210 documented pieces have been added to the treasury since its inception, typically to receive in return legitimisation of linkage to the heritage of Charlemagne. The Lothar Cross, the Gospels of Otto III and multiple additional Byzantine silks were donated by Otto III. Part of the Pala d'Oro and a covering for the Aachen Gospels were made of gold donated by Henry II.[63] Frederick Barbarossa donated the candelabrum that adorns the dome and also once "crowned" the Shrine of Charlemagne, which was placed underneath in 1215. Charles IV donated a pair of reliquaries. Louis XI gave, in 1475, the crown of Margaret of York, and, in 1481, another arm reliquary of Charlemagne. Maximilian I and Charles V both gave numerous works of art by Hans von Reutlingen.[63] Continuing the tradition, objects continued to be donated until the present, each indicative of the period of its gifting, with the last documented gift being a chalice from 1960 made by Ewald Mataré.[63]

Aachen Rathaus

The Aachen Rathaus, (English: Aachen City Hall or Aachen Town Hall) dated from 1330,[24] lies between two central squares, the Markt (marketplace) and the Katschhof (between city hall and cathedral). The coronation hall is on the first floor of the building. Inside one can find five frescoes by the Aachen artist Alfred Rethel which show legendary scenes from the life of Charlemagne, as well as Charlemagne's signature. Also, precious replicas of the Imperial Regalia are kept here.[66]

Since 2009, the city hall has been a station on the Route Charlemagne, a tour programme by which historical sights of Aachen are presented to visitors. At the city hall, a museum exhibition explains the history and art of the building and gives a sense of the historical coronation banquets that took place there. A portrait of Napoleon from 1807 by Louis-André-Gabriel Bouchet and one of his wife Joséphine from 1805 by Robert Lefèvre are viewable as part of the tour.

As before, the city hall is the seat of the mayor of Aachen and of the city council, and annually the Charlemagne Prize is awarded there.

Other sights

The Grashaus, a late medieval house at the Fischmarkt, is one of the oldest non-religious buildings in central Aachen. It hosted the city archive, and before that, the Grashaus was the city hall until the present building took over this function.

The Elisenbrunnen is one of the most famous sights of Aachen. It is a neo-classical hall covering one of the city's famous fountains. It is just a minute away from the cathedral. Just a few steps in a south-easterly direction lies the 19th-century theatre.

Also of note are two remaining city gates, the Ponttor (Pont gate), 800 metres (1⁄2 mile) northwest of the cathedral, and the Marschiertor (marching gate), close to the central railway station. There are also a few parts of both medieval city walls left, most of them integrated into more recent buildings, but some others still visible. There are even five towers left, some of which are used for housing.

St. Michael's Church, Aachen was built as a church of the Aachen Jesuit Collegium in 1628. It is attributed to the Rhine mannerism, and a sample of a local Renaissance architecture. The rich façade remained unfinished until 1891, when the architect Peter Friedrich Peters added to it. The church is a Greek Orthodox church today, but the building is used also for concerts because of its good acoustics.

The synagogue in Aachen, which was destroyed on the Night of Broken Glass (Kristallnacht), 9 November 1938, was reinaugurated on 18 May 1995.[68][69] One of the contributors to the reconstructions of the synagogue was Jürgen Linden, the Lord Mayor of Aachen from 1989 to 2009.

There are numerous other notable churches and monasteries, a few remarkable 17th- and 18th-century buildings in the particular Baroque style typical of the region, a synagogue, a collection of statues and monuments, park areas, cemeteries, among others. Among the museums in the town are the Suermondt-Ludwig Museum, which has a fine sculpture collection and the Aachen Museum of the International Press, which is dedicated to newspapers from the 16th century to the present.[70] The area's industrial history is reflected in dozens of 19th- and early 20th-century manufacturing sites in the city.

Grashaus

Grashaus Elisenbrunnen in Aachen

Elisenbrunnen in Aachen Aachen Theatre

Aachen Theatre Neues Kurhaus

Neues Kurhaus- Carolus Thermen, thermal baths named after Charlemagne

- A statue commemorating David Hansemann

Economy

Aachen is the administrative centre for the coal-mining industries in neighbouring places to the northeast.[20]

Products manufactured in Aachen include electrical goods, textiles, foodstuffs (chocolate and candy), glass, machinery, rubber products, furniture, metal products.[60] Also in and around Aachen chemicals, plastics, cosmetics, and needles and pins are produced.[29] Though once a major player in Aachen's economy, today glassware and textile production make up only 10% of total manufacturing jobs in the city.[13] There have been a number of spin-offs from the university's IT technology department.

Electric vehicle manufacturing

In June 2010, Achim Kampker, together with Günther Schuh, founded a small company to develop Street Scooter GmbH; in August 2014, it was renamed StreetScooter GmbH. This was a privately organised research initiative at the RWTH Aachen University which later became an independent company in Aachen. Kampker was also the founder and chairman of the European Network for Affordable and Sustainable Electromobility. In May 2014, the company announced that the city of Aachen, the city council Aachen and the savings bank Aachen had ordered electric vehicles from the company. In late 2014, approximately 70 employees were manufacturing 200 vehicles annually in the premises of the Waggonfabrik Talbot, the former Talbot/Bombardier plant in Aachen.[71]

In December 2014 Deutsche Post DHL Group purchased the StreetScooter company, which became its wholly owned subsidiary.[72] By April 2016, the company announced that it would produce 2000 of its electric vans branded Work in Aachen by the end of the year.

In 2015, the electric vehicle start-up e.GO Mobile was founded by Günther Schuh, which started producing the e.GO Life electric passenger car and other vehicles in April 2019.

In April 2016, StreetScooter GmbH announced that it would be scaling up to manufacture approximately 10,000 of the Work vehicles annually, starting in 2017, also in Aachen.[73] If that goal is achieved, it will become the largest electric light utility vehicle manufacturer in Europe, surpassing Renault which makes the smaller Kangoo Z.E..[74]

Culture

- In 1372, Aachen became the first coin-minting city in the world to regularly place an anno Domini date on a general circulation coin, a groschen.

- The Scotch Club in Aachen was the first discothèque; it has been open since 19 October 1959. Klaus Quirini as DJ Heinrich was the first DJ ever.

- The thriving Aachen black metal scene is among the most notable in Germany, with such bands as Nagelfar, The Ruins of Beverast, Graupel and Verdunkeln.

- The local speciality of Aachen is an originally hard type of sweet bread, baked in large flat loaves, called Aachener Printen. Unlike Lebkuchen, a German form of gingerbread sweetened with honey, Printen use a syrup made from sugar. Today, a soft version is sold under the same name which follows an entirely different recipe.

- Asteroid 274835 Aachen, discovered by amateur astronomer Erwin Schwab in 2009, was named after the city.[75] The official naming citation was published by the Minor Planet Center on 8 November 2019 (M.P.C. 118221).[76]

Education

RWTH Aachen University, established as Polytechnicum in 1870, is one of Germany's Universities of Excellence with strong emphasis on technological research, especially for electrical and mechanical engineering, computer sciences, physics, and chemistry. The university clinic attached to the RWTH, the Klinikum Aachen, is the biggest single-building hospital in Europe.[77] Over time, a host of software and computer industries have developed around the university. It also maintains a botanical garden (the Botanischer Garten Aachen).

FH Aachen, Aachen University of Applied Sciences (AcUAS) was founded in 1971. The AcUAS offers a classic engineering education in professions such as mechatronics, construction engineering, mechanical engineering or electrical engineering. German and international students are educated in more than 20 international or foreign-oriented programmes and can acquire German as well as international degrees (Bachelor/Master) or Doppelabschlüsse (double degrees). Foreign students account for more than 21% of the student body.

The Katholische Hochschule Nordrhein-Westfalen – Abteilung Aachen (Catholic University of Applied Sciences Northrhine-Westphalia – Aachen department)[78] offers its some 750 students a variety of degree programmes: social work, childhood education, nursing, and co-operative management. It also has the only programme of study in Germany especially designed for mothers.[79]

The Hochschule für Musik und Tanz Köln (Cologne University of Music) is one of the world's foremost performing arts schools and one of the largest music institutions for higher education in Europe[80] with one of its three campuses in Aachen.[81] The Aachen campus substantially contributes to the Opera/Musical Theatre master's programme by collaborating with the Theater Aachen and the recently established musical theatre chair through the Rheinische Opernakademie.

The German army's Technical School (Ausbildungszentrum Technik Landsysteme) is in Aachen.[82]

Sports

The annual CHIO (short for the French term Concours Hippique International Officiel) is the biggest equestrian meeting of the world and among horsemen is considered to be as prestigious for equitation as the tournament of Wimbledon for tennis. Aachen hosted the 2006 FEI World Equestrian Games.

The local football team Alemannia Aachen had a short run in Germany's first division, after its promotion in 2006. However, the team could not sustain its status and is now back in the fourth division. The stadium "Tivoli", opened in 1928, served as the venue for the team's home games and was well known for its incomparable atmosphere throughout the whole of the second division.[83] Before the old stadium's demolition in 2011, it was used by amateurs, whilst the Bundesliga Club held its games in the new stadium "Neuer Tivoli" – meaning New Tivoli—a couple of metres down the road. The building work for the stadium which has a capacity of 32,960, began in May 2008 and was completed by the beginning of 2009.

The Ladies in Black women's volleyball team (part of the "PTSV Aachen" sports club since 2013) has played in the first German volleyball league (DVL) since 2008.

Transport

Rail

Aachen's railway station, the Hauptbahnhof (Central Station), was constructed in 1841 for the Cologne–Aachen railway line. In 1905 it was moved closer to the city centre. It serves main lines to Cologne, Mönchengladbach and Liège as well as branch lines to Heerlen, Alsdorf, Stolberg and Eschweiler. ICE high speed trains from Brussels via Cologne to Frankfurt am Main and Thalys trains from Paris to Cologne also stop at Aachen Central Station. Four RE lines and two RB lines connect Aachen with the Ruhrgebiet, Mönchengladbach, Spa (Belgium), Düsseldorf and the Siegerland. The Euregiobahn, a regional railway system, reaches several minor cities in the Aachen region.

There are four smaller stations in Aachen: Aachen West, Aachen Schanz, Aachen-Rothe Erde and Eilendorf. Slower trains stop at these. Aachen West has gained in importance with the expansion of RWTH Aachen University.

Intercity bus stations

There are two stations for intercity bus services in Aachen: Aachen West station, in the north-west of the city, and Aachen Wilmersdorfer Straße, in the north-east.[84]

Public transport

The first horse tram line in Aachen opened in December 1880. After electrification in 1895, it attained a maximum length of 213.5 kilometres (132 5⁄8 miles) in 1915, becoming the fourth-longest tram network in Germany. Many tram lines extended to the surrounding towns of Herzogenrath, Stolberg, Alsdorf as well as the Belgian and Dutch communes of Vaals, Kelmis (then Altenberg) and Eupen. The Aachen tram system was linked with the Belgian national interurban tram system. Like many tram systems in Western Europe, the Aachen tram suffered from poorly-maintained infrastructure and was so deemed unnecessary and disrupting for car drivers by local politics. On 28 September 1974 the last line 15 (Vaals–Brand) operated for one last day and was then replaced by buses. A proposal to reinstate a tram/light rail system under the name Campusbahn was dropped after a referendum.

Today, the ASEAG (Aachener Straßenbahn und Energieversorgungs-AG, literally "Aachen tram and power supply company") operates a 1,240.8-kilometre-long (771 mi) bus network with 68 bus routes. Because of the location at the border, many bus routes extend to Belgium and the Netherlands. Lines 14 to Eupen, Belgium and 44 to Heerlen, Netherlands are jointly operated with Transport en Commun and Veolia Transport Nederland, respectively. ASEAG is one of the main participants in the Aachener Verkehrsverbund (AVV), a tariff association in the region. Along with ASEAG, city bus routes of Aachen are served by private contractors such as Sadar, Taeter, Schlömer, or DB Regio Bus. Line 350, which runs from Maastricht, also enters Aachen.

Roads

Aachen is connected to the Autobahn A4 (west-east), A44 (north-south) and A544 (a smaller motorway from the A4 to the Europaplatz near the city centre). There are plans to eliminate traffic jams at the Aachen road interchange.

Airport

Maastricht Aachen Airport (IATA: MST, ICAO: EHBK) is the main airport of Aachen and Maastricht. It is located around 15 nautical miles (28 km; 17 mi) northwest of Aachen. There is a shuttle-service between Aachen and the airport.

Recreational aviation is served by the (formerly military) Aachen Merzbrück Airfield.

Charlemagne Prize

Since 1950, a committee of Aachen citizens annually awards the Charlemagne Prize (German: Karlspreis) to personalities of outstanding service to the unification of Europe. It is traditionally awarded on Ascension Day at the City Hall. In 2016, the Charlemagne Award was awarded to Pope Francis.

The International Charlemagne Prize of Aachen was awarded in the year 2000 to US president Bill Clinton, for his special personal contribution to co-operation with the states of Europe, for the preservation of peace, freedom, democracy and human rights in Europe, and for his support of the enlargement of the European Union. In 2004, Pope John Paul II's efforts to unite Europe were honoured with an "Extraordinary Charlemagne Medal", which was awarded for the only time ever.

Notable people

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Aachen is twinned with:[85]

See also

Notes

- UK: /ˌɛks lə ʃəˈpɛl/, US: /ˌɛks lɑː ʃɑːˈpɛl, ˌeɪks-/,[3][4] French: [ɛks la ʃapɛl].

- "RWTH" is the abbreviation of "Rheinisch-Westfälische Technische Hochschule", which translates into "Rhine-Westphalian Technical University". The institution is commonly referred to as "RWTH Aachen" or simply "RWTH", with the abbreviation remaining untranslated in other languages to avoid the use of the "Hochschule" term, which is sometimes mistakenly translated as high school. Sometimes, RWTH Aachen is also referred to as "TH Aachen" or "Aachen University". However, the term "FH Aachen" does not refer to the RWTH but to the Fachhochschule Aachen, a university of applied sciences, which is also in Aachen.

- This audio file is Andreas Schaub explaining the archaeological record in court in Archäologie am Hof.

- This is in dispute, as some history books state that Charlemagne was in fact born in Aachen in 742.[24]

- This was between 970 and 980.[26]

- Sources differ on the age of the city hall, as the dates used for the construction were 1334–1349.[20]

- Twinning started by then independent municipality Walheim, now continued by borough Aachen-Kornelimünster/Walheim.[86]

References

- "Bevölkerung der Gemeinden Nordrhein-Westfalens am 31. Dezember 2018" (in German). Landesbetrieb Information und Technik NRW. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- "Aachen". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- "Aachen". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- "Aix-la-Chapelle" (US) and "Aix-la-Chapelle". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- Young & Stetler 1987, p. 272.

- Mueller, Joerg (26 July 2017). "Aachen | Historic Highlights of Germany". www.historicgermany.travel. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- Munro 1995, p. 1.

- Bridgwater & Aldrich 1968, p. 11.

- Bayer 2000, p. 1.

- RWTH Aachen University 2013.

- Anon 2009.

- Mielke 2013.

- Kerner 2013

- Egger 1977, p. 15

- Canby 1984, p. 1

- Anon 2013.

- Schumacher 2009.

- Anon 2013a.

- Freimann 1906, p. 301.

- McClendon 1996, p. 1.

- Held 1997, p. 2.

- McClendon 1996a, p. 1.

- Eginhard 2012, p. 10.

- Merkl 2007, p. 2

- McClendon 1996a, p. 4.

- Dupuy & Dupuy 1986, p. 258.

- Kitchen 1996, p. 35.

- Kitchen 1996, p. 40.

- Ranson 1998, p. 45.

- De Jong 1996, p. 279

- McKitterick 1996, p. 1.

- Holborn 1982, p. 295.

- Encyclopædia Britannica Online 2006.

- "Fabricius, François", in Dictionnaire des sciences médicales: biographie médicale, vol. 4 (Paris, C. L. F. Panckoucke, 1821), p. 92. On Google Books.

- Dupuy & Dupuy 1986, p. 563.

- Holborn 1982a, p. 70.

- Holborn 1982a, p. 217.

- Wilson 2004, p. 301.

- Holborn 1982b, p. 11.

- Van der Gragt 1968, p. 137.

- Holborn 1982b, p. 614.

- Friedrich 2008, p. 117.

- Stanton 2006, p. 76.

- Stanton 2006, p. 51.

- Stanton 2006, p. 50.

- Stanton 2006, p. 109.

- Stanton 2006, p. 105.

- Baker 2004, p. 37.

- "Baghdad, Jerusalem, Aachen -- On the Trail of the White Elephant". Deutsche Welle. 21 July 2003. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- Anon 2013b.

- Aachen Department of Environment 2013.

- Federal Ministry of Transport, Building, and Urban Development 2013.

- Anderson, Ernest Masson (2012). Healy, David (ed.). Faulting, Fracturing and Igneous Intrusion in the Earth's Crust. 367. Geological Society of London. ISBN 978-1-86239-347-9. ISSN 0305-8719.

- University of Cologne, Seismological Station Bensberg 2013.

- Geological Survey of North Rhine-Westphalia 2013.

- Information und Technik Nordrhein-Westfalen. "Bevölkerung im Regierungsbezirk Köln". Archived from the original on 8 April 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- Aktualisierung 2012.

- City of Aachen 2012.

- RWTH Aachen University 2013a.

- Cohen 1998, p. 1.

- "Aachen zählt jetzt mehr als 257.000 Bürger". Aachener Zeitung. 25 January 2019.

- McClendon 1996a, p. 2.

- Gaehde 1996, p. 4.

- McClendon 1996a, p. 3.

- City of Aachen 2013.

- Young & Stetler 1987, p. 273.

- "Aachen | Germany". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise 2013.

- Knufinke 2013.

- Hoiberg 2010, pp. 1–2.

- "Deutsche Post DHL acquires StreetScooter GmbH". DHL. DHL. 9 December 2014. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- Deutsche Post DHL übernimmt StreetScooter GmbH 9.

- "Streetscooter – Der tausendste Elektro-Transporter der Post". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung GmbH. 23 August 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

Die Post will ihren gesamten Fuhrpark auf Elektro-Autos umstellen. Bis dahin dauert es noch. Einen wichtigen Schritt hat das Unternehmen nun aber gemacht.

- Weiss, Richard (24 March 2017). "Even Germany's post office is building an electric car". Waterloo Region Record. Kitchener, Ontario. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- "(274835) Aachen". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- "MPC/MPO/MPS Archive". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Aachen Institute for Advanced Study in Computational Engineering Science 2009.

- Catholic University of Applied Sciences 2014.

- Catholic University of Applied Sciences 2014a.

- Academy of Music and Dance Cologne 2014.

- Academy of Music and Dance Cologne 2014a.

- Van der Meer, Richter & Opitz 1998, p. 718.

- Gdawietz & Leroi 2008, p. 28.

- Travelinho. "Aachen: Stations". Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- "Städtepartnerschaften". aachen.de (in German). Aachen. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- "Montebourg – Frankreich". Retrieved 3 November 2016.

Sources

- Aachen Department of Environment (2013). "Stadtklima" [Urban Climate] (in German). Retrieved 9 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Aachen Institute for Advanced Study in Computational Engineering Science (2009). "About Aachen". RWTH Aachen University. Retrieved 9 February 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Academy of Music and Dance Cologne (2014). "Profile" (in German). Cologne University of Music. Retrieved 3 August 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Academy of Music and Dance Cologne (2014a). "Homepage" (in German). Cologne University of Music. Archived from the original on 25 July 2014. Retrieved 3 August 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Anon (28 July 2009). "2thinknow Innovation Cities™ Global 256 Index". Innovation Cities. Archived from the original on 9 April 2014. Retrieved 4 September 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ActiLingua Academy (2013). "The German Language and Its Many Forms". Vienna. Retrieved 4 September 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Anon (2013). "Aachen – römische Bäderstadt: Badeleben in einer römischen Therme" [Aachen – City Roman Baths: Life in a Roman thermal bath]. Archaeology in Aachen (in German). Retrieved 9 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wetter – Deutschland (4 September 2016). "Wetter Aachen" [Aachen Weather] (in German). Retrieved 4 September 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- DB – City (2013). "Aachen, Aachen, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany – City, Town and Village of the world". Retrieved 9 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Anon (2014). "Search: Aachen". The Coordination Forum for Countering Antisemitism. Archived from the original on 29 April 2015. Retrieved 31 July 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Aktualisierung, Letzte (2 May 2012). "Aachen: Wieder mehr Arbeitslose" [Aachen: Again, More Unemployed]. Aachener Nachrichten (in German). Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise (2013). "The Holocaust:Photographs". Jewish Virtual Library. American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise. Retrieved 9 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise (2013a). "The Holocaust:Photographs". Jewish Virtual Library. American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise. Retrieved 28 January 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Baker, Anni P. (2004). American Soldiers Overseas: The Global Military Presence. Perspectives on the Twentieth Century. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-275-97354-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bayer, Patricia, ed. (2000). "Aachen". Encyclopedia Americana. I A-Anjou (1st ed.). Danbury, CT: Grolier Incorporated. ISBN 0-7172-0133-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bridgwater, W.; Aldrich, Beatrice, eds. (1968). "Aachen". The Columbia-Viking Desk Encyclopædia (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ASIN B000UUM90Y.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Calderdale Council (2012). "Aachen: Twin Towns". Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 9 February 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Canby, Courtlandt (1984). "Aachen". In Carruth, Gorton (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Historic Places. I: A-L. New York, NY: Fact on File Publications. ISBN 0-87196-126-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Catholic University of Applied Sciences (2014). "Homepage". Catholic University of Applied Sciences. Archived from the original on 9 July 2014. Retrieved 3 August 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Catholic University of Applied Sciences (2014a). "Aachen". Catholic University of Applied Sciences. Archived from the original on 29 July 2014. Retrieved 3 August 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- City of Aachen (2012). "Bevölkerungsstand" [Population as of] (in German). aachen.de. Retrieved 9 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- City of Aachen (2013). "Cathedral of Aachen". City of Aachen. Archived from the original on 26 September 2013. Retrieved 9 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cohen, Saul B., ed. (1998). "Aachen". The Columbia Gazetteer of the World. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-11040-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- De Jong, Mayke (1996). In Samuel's Image: Child Oblation in the Early Medieval West. Leiden, Netherlands: E. J. Brill. ISBN 90-04-10483-6. LCCN 95025956.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dupuy, R. Ernest; Dupuy, Trevor N. (1986). The Encyclopedia of Military History from 3500 B.C. to the Present (2nd Revised ed.). New York, NY: Harper & Row, Publishers. ISBN 0-06-181235-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Egger, Carlo (1977). Lexicon nominum locorum [Lexicon of Place Names] (in Latin). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. ISBN 978-88-209-1254-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eginhard (2012) [1824]. Annales D'Eginhard; Vie de Charlemagne. Des Faits Et Gestes de Charlemagne [Annals of Eginhard Life of Charlemagne. Facts and gestures of Charlemagne] (in French). Hachette Livre – Bnf. ISBN 978-2-01-252304-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Aachen". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2006. Retrieved 8 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Federal Ministry of Transport, Building, and Urban Development (2013). "Ausgabe der Klimadaten: Monatswerte" [Issue of climate data: monthly data] (in German). Retrieved 9 February 2014.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Freimann, A. J. (1906). "Aix-La-Chapelle (Aachen)". In Singer, Isidore (ed.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. 1: Aach – Apocalyptic Lit. New York, NY: KTAV Publishing House.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Friedrich, Jörg (2008). The Fire: The Bombing of Germany, 1940–1945. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231133814.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gaehde, Joachim E. (1996). "Aachen: Buildings: Palatine Chapel: Sculpture and Treasury". In Turner, Jane; Brigstocke, Hugh (eds.). The Dictionary of Art. 1: A to Anckerman. New York, NY: Grove. pp. 4–5. ISBN 0-19-517068-7. LCCN 96013628.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gdawietz, Gregor; Leroi, Roland (2008). Von Aachen bis Bielefeld – Vom Tivoli zur Alm [From Aachen to Bielefeld – From Tivoli to the Pasture] (in German). Aachen, Germany: Meyer + Meyer Fachverlag. ISBN 978-3-89899-315-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Geological Survey of North Rhine-Westphalia (2013). "Erdbeben bei Roermond am 13. April 1992" [Earthquake in Roermond on 13 April 1992] (PDF) (in German). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 9 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Held, Colbert C. (1997). "Aachen". In Johnston, Bernard (ed.). Collier's Encyclopedia. I: A to Ameland (1st ed.). New York, NY: P. F. Collier.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hoiberg, Dale H., ed. (2010). "Aachen". Encyclopædia Britannica. I: A-Ak – Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, IL: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Holborn, Hajo (1982) [1959]. A History of Modern Germany. 1: The Reformation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00795-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Holborn, Hajo (1982a) [1964]. A History of Modern Germany. 2: 1648–1840. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00796-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Holborn, Hajo (1982b) [1969]. A History of Modern Germany. 3: 1840–1945. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00797-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kerner, Maximillian (2013). "Aachen and Europe". City of Aachen. Archived from the original on 18 February 2014. Retrieved 9 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kitchen, Martin (1996). The Cambridge Illustrated History of Germany. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-45341-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Knufinke, Ulrich (2013). "Aachen: Synagoge und Gemeindezentrum Synagogenplatz" [Aachen: Synagogue and community centre Synagogenplatz]. Zentralrat der Juden in Deutschland. Retrieved 9 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McClendon, Charles B. (1996). "Aachen". In Turner, Jane; Brigstocke, Hugh (eds.). The Dictionary of Art. 1: A to Anckerman. New York, NY: Grove. ISBN 0-19-517068-7. LCCN 96013628.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McClendon, Charles B. (1996a). "Aachen: Buildings". In Turner, Jane; Brigstocke, Hugh (eds.). The Dictionary of Art. 1: A to Anckerman. New York, NY: Grove. pp. 1–4. ISBN 0-19-517068-7. LCCN 96013628.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McKitterick, Rosamond D. (1996). "Aachen: Centre of Manuscript Production". In Turner, Jane; Brigstocke, Hugh (eds.). The Dictionary of Art. 1: A to Anckerman. New York, NY: Grove. ISBN 0-19-517068-7. LCCN 96013628.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Merkl, Peter H. (2007). "Aachen". In Kobasa, Paul A. (ed.). World Book. I: A (1st ed.). Chicago, IL: World Book Inc. ISBN 978-0-7166-0107-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mielke, Rita (2013). "History of Bathing". City of Aachen. Retrieved 9 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Munro, David, ed. (1995). "Aachen (Aix-la-Chapelle)". The Oxford Dictionary of the World. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-866184-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pecinovský, Jindřich (1 December 2009). "Partnerská města Kladna" [Partner of Kladno] (in Czech). Retrieved 9 February 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ranson, K. Anne, ed. (1998). "Aachen". Academic American Encyclopedia. I: A – Ang (First ed.). Danbury, CT: Grolier Incorporated. ISBN 0-7172-2068-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- RWTH Aachen University (2013). "Excellence Initiative". RWTH Aachen University. Retrieved 9 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- RWTH Aachen University (31 May 2016). "Internationalisierung" [Internationalisation] (PDF). Aachen University. Retrieved 4 September 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schäfer, Burkhard; Schäfer, Sibylle (2010). "Biography David Garrett". David Garrett.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schaub, Andreas (2013). Andreas Schaub explains the archaeological record in court in Archäologie am Hof. City of Aachen (MP3) (Audio) (in German). Retrieved 9 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schmetz, Oliver (2011). "Bestürzung über Nazi-Attacke auf Synagoge" [Dismay over Nazi attack on synagogue]. Aachener Zeitung. Retrieved 9 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schumacher, Wolfgang (23 January 2009). "Keltisches Glas und eine römische Villa im Elisengarten" [Celtic glass and a Roman villa in Elisengarten]. Aachener Nachrichten (in German). Retrieved 9 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Der Spiegel (9 May 2013). "Karlspreis-Trägerin Grybauskaite: Macht eure Hausaufgaben!" [Charlemagne Prize winner Grybauskaite: Does your homework!] (in German). Hamburg. Retrieved 4 September 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stanton, Shelby L. (2006) [1984]. World War II Order of Battle: An Encyclopedic Reference to U.S. Army Ground Forces from Battalion through Division, 1939–1946 (2nd ed.). Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0157-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- University of Cologne, Seismological Station Bensberg (2013). "Zum 250. Jahrestag des Dürener Erdbebens" [The 250th Anniversary of the Düren earthquake] (in German). Retrieved 9 February 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Van der Gragt, F. (1968). Europe's Greatest Tramways Network. Leiden, Netherlands: E. J. Brill. ASIN B000MOT6T0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Van der Meer, Willemina; Richter, Elisabeth; Opitz, Helmut, eds. (1998). World guide to special libraries. 2 (4th ed.). K G Saur Verlag Gmbh & Co. ISBN 978-3-598-22249-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilson, Peter H. (2004). Black, Jeremy (ed.). From Reich to Revolution: German History, 1558–1806. European History in Perspective. Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-65244-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Young, Margaret Walsh; Stetler, Susan L., eds. (1987). "Germany, Federal Republic of". Aachen. Cities of the World. 3: Europe and the Mediterranean Middle East (3rd ed.). Detroit, MI: Gale Research Company. ISBN 0-8103-2541-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Hunt, Frederick Knight (1845). "Interchapter – Aix-la-Chapelle". The Rhine: Its Scenery, and Historical and Legendary Associations. London, UK: Jeremiah How. pp. 77–83. LCCN 04028368.

- Murray, John (1845) [1837]. A Hand-book for Travellers on the Continent: Being a Guide Through Holland, Belgium, Prussia, and Northern Germany, and Along the Rhine, from Holland to Switzerland (5th ed.). London, UK: John Murray and Son. pp. 216–222. LCCN 14015908.

- Baedeker, Karl (1911) [1868]. The Rhine, including the Black Forest & the Vosges. Baedeker's Guide Books (17th ed.). Leipzig, Germany: Karl Baedeker, Publishers. pp. 12–15. LCCN 11015867. OL 6532082M.

- Bischoff, Bernhard (1981). "Die Hofbibliothek Karls des Grossen [The Court Library of Charlemagne] and Die Hofbibliothek unter Ludwig dem Frommen [The Court Library under Louis the Pious]". Mittelalterliche Studien [Medieval Studies] (in German). III. Stuttgart, Germany: A. Hiersemann. pp. 149–186.

- Braunfels, Wolfgang; Schnitzler, H., eds. (1966). Karl der Grosse: Lebenswerk und Nachleben [Charlemagne: Lifetime and Legacy] (in German). Düsseldorf, Germany: L. Schwann. LCCN 66055599.

- Cüppers, von Heinz (1982). Aquae Granni: Beiträge zur Archäologie von Aachen: Rheinische Ausgrabungen [Aquae Granni: Contributions to Archaeology of Aachen: Excavations of the Rhineland] (in German). Cologne, Germany: Rheinland-verlag. ISBN 3-7927-0313-0. LCCN 82178009.

- Faymonville, D. (1916). Die Kunstdenkmäler der Stadt Aachen [The Monuments of the City of Aachen] (in German). Düsseldorf, Germany: L. Schwann.

- Grimme, Ernst Günther (1972). Der Aachener Domschatz [The Aachen Cathedral Treasury]. Aachener Kunstblätter [Written Works on Aachen] (in German). Düsseldorf, Germany: L. Schwann. LCCN 72353488.

- Kaemmerer, Walter (1955). Geschichtliches Aachen: Von Werden und Wesen einer Reichsstadt [History of Aachen: From Will and Essence of an Imperial City] (in German). Aachen, Germany: M. Brimberg. LCCN 56004784.

- Koehler, Wilhelm Reinhold Walter (1958). Die karolingischen Miniaturen [The Carolingian Miniatures] (in German). II-IV. Berlin, Germany: B. Cassirer. LCCN 57050855.

- McKitterick, Rosamond (1990). "Carolingian Uncial: A Context for the Lothar Psalter" (PDF). The British Library Journal. British Library. 16 (1): 1–15.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Aachen. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aachen. |

- Official website