South African English

South African English (SAfrE, SAfrEng, SAE, en-ZA)[1] is the set of English dialects native to South Africans.

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of South Africa |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Cuisine |

|

Festivals |

| Religion |

| Art |

|

Media |

| Sport |

|

Monuments |

|

| Part of a series on |

| The English language |

|---|

| Topics |

|

| Advanced topics |

|

| Phonology |

| Dialects |

|

| Teaching |

Higher category: Language |

History

British colonists first colonised the South African region in 1795, when they established a military holding operation at the Cape Colony. The goal of this first endeavour was to gain control of a key Cape sea route, not to establish a permanent settler colony.[2] The first major influx of English speakers arrived in 1820. About 5000 British settlers, mostly rural or working class, settled in the eastern Cape.[2] Though the British were a minority colonist group (the Dutch had been in the region since 1652, when traders from the Dutch East India Company developed an outpost), the Cape Colony governor, Lord Charles Somerset, declared English an official language in 1822.[2] To spread the influence of English in the colony, officials began to recruit British schoolmasters and Scottish clergy to occupy positions in the education and church systems.[2] Another group of English speakers arrived from Britain in the 1840s and 1850s, along with the Natal settlers. These individuals were largely "standard speakers" like retired military personnel and aristocrats.[2] A third wave of English settlers arrived between 1875 and 1904, and brought with them a diverse variety of English dialects. These last two waves did not have as large of an influence on South African English (SAE), for "the seeds of development were already sown in 1820".[2] However, the Natal wave brought nostalgia for British customs and helped to define the idea of a "standard" variety that resembled Southern British English.[2]

When the Union of South Africa was formed in 1910, English and Dutch were the official state languages, although Afrikaans effectively replaced Dutch in 1925.[3] After 1994, these two languages along with nine other Southern Bantu languages achieved equal official status.[3]

SAE is an extraterritorial (ET) variety of English, or a language variety that has been transported outside its mainland home. More specifically, SAE is a Southern hemisphere ET originating from later English colonisation in the 18th and 19th centuries (Zimbabwean, Australian, and New Zealand English are also Southern hemisphere ET varieties).[2] SAE resembles British English more closely than it does American English due to the close ties that South African colonies maintained with the mainland in the 19th and 20th centuries. However, with the increasing influence of American pop-culture around the world via modes of contact like television, American English has become more familiar in South Africa. Indeed, some American lexical items are becoming alternatives to comparable British terms.[2]

Varieties

White South African English

Several South African English varieties have emerged, accompanied by varying levels of perceived social prestige. Roger Lass describes White South African English as a system of three sub-varieties spoken primarily by White South Africans, called "The Great Trichotomy" (a term first used to categorise Australian English varieties and subsequently applied to South African English).[2] In this classification, the "Cultivated" variety closely approximates England's standard Received Pronunciation and is associated with the upper class; the "General" variety is a social indicator of the middle class and is the common tongue; and the "Broad" variety is most associated with the working class, low socioeconomic status, and little education.[2] These three sub-varieties have also been called "Conservative SAE", "Respectable SAE", and "Extreme SAE", respectively.[2] Broad White SAE closely approximates the second-language variety of (Afrikaans-speaking) Afrikaners called Afrikaans English. This variety has been stigmatised by middle and upper class SAE speakers and is considered a vernacular form of SAE.[2]

Black South African English

Black South African English, or BSAE, is spoken by individuals whose first language is an indigenous African tongue.[4] BSAE is considered a "new" English because it has emerged through the education system among second-language speakers in places where English is not the majority language.[4] At least two sociolinguistic variants have been definitively studied on a post-creole continuum for the second-language Black South African English spoken by most Black South Africans: a high-end, prestigious "acrolect" and a more middle-ranging, mainstream "mesolect". The "basilect" variety is less similar to the colonial language (natively-spoken English), while the "mesolect" is somewhat more so.[2] Historically, BSAE has been considered a "non-standard" variety of English, inappropriate for formal contexts and influenced by indigenous African languages.[4]

According to the Central Statistical Services, as of 1994 about 7 million black people spoke English in South Africa.[4] BSAE originated in the South African school system, when the 1953 Bantu Education Act mandated the use of native African languages in the classroom. When this law was established, most of the native English-speaking teachers were removed from schools. This limited the exposure that black students received to standard varieties of English. As a result, the English spoken in black schools developed distinctive patterns of pronunciation and syntax, leading to the formation of BSAE.[4] Some of these characteristic features can be linked to the mother tongues of the early BSAE speakers. The policy of mother tongue promotion in schools ultimately failed, and in 1979, the Department of Bantu Education allowed schools to choose their own language of instruction. English was largely the language of choice, because it was viewed as a key tool of social and economic advancement.[4]

Indian South African English

Indian South African English (ISAE) is a sub-variety that developed among the descendants of Indian immigrants to South Africa.[2] The Apartheid policy, in effect from 1948 to 1991, prevented Indian children from publicly interacting with people of English heritage. This separation caused an Indian variety to develop independently from White South African English, though with phonological and lexical features still fitting under the South African English umbrella.[2] Indian South African English includes a "basilect", "mesolect", and "acrolect".[2] These terms describe varieties of a given language on a spectrum of similarity to the colonial version of that language: the "acrolect" being the most similar.[2] Today, basilect speakers are generally older non-native speakers with little education; acrolect speakers closely resemble colonial native English speakers, with a few phonetic/syntactic exceptions; and mesolect speakers fall somewhere in-between.[2]

ISAE resembles Indian English in some respects, possibly because the varieties contain speakers with shared mother tongues or because early English teachers were brought to South Africa from India, or both.[2] Four prominent education-related lexical features shared by ISAE and Indian English are: tuition(s), which means "extra lessons outside school that one pays for"; further studies, which means "higher education"; alphabets, which means "the alphabet, letters of the alphabet"; and by-heart, which means "to learn off by heart"; these items show the influence of Indian English teachers in South Africa.[2] Phonologically, ISAE also shares several similarities with Indian English, though certain common features are decreasing in the South African variety. For instance, consonant retroflexion in phonemes like /ḍ/ and strong aspiration in consonant production (common in North Indian English) are present in both varieties, but declining in ISAE. Syllable-timed rhythm, instead of stress-timed rhythm, is still a prominent feature in both varieties, especially in more colloquial sub-varieties.[2]

Cape Flats English

Another variety of South African English is Cape Flats English, originally and best associated with inner-city Cape Coloured speakers.[5]

Phonology

Vowels

- Allophonic variation in the KIT vowel (from Wells' 1982 lexical sets). In some contexts, such as after /h/, the KIT vowel is pronounced [ɪ]; before tautosyllabic /l/ it is pronounced [ɤ]; and in other contexts it is pronounced [ə].[6] This feature is not present in Conservative SAE, and may have resulted from a vocalic chain shift in White SAE.[2]

- Pronunciation of the FLEECE vowel with the long monophthongal [iː]. In contrast, other Southern Hemisphere Englishes like Australian English and New Zealand English have diphthongised FLEECE ([ɪi ~ əi]).[6]

- Back BATH, with lip rounding in the broader dialects ([ɑː] or [ɒː]). This differs from Australian English and New Zealand English, which have central [aː] instead.[6]

- Short TRAP ([æ]), resulting in a BATH/TRAP split. Australian English and New Zealand English also demonstrate this split.[2]

- LOT is short, open, weakly rounded, and centralised, around [ɒ̽].[2]

- FOOT is short, half-closed back and centralised, around [ʊ].[2]

- NURSE tends to resemble the Received Pronunciation non-rhotic [ɜː] among Conservative SAE speakers, while the vowel is front, half-close, centralised [øː] in other varieties.[2]

Consonants

- In Conservative and Respectable SAE, /h/ is the voiceless glottal fricative [h]. In Extreme SAE, /h/ has a more breathy-voiced pronunciation, [ɦ]. /h/ is sometimes deleted in Extreme SAE where it is preserved in Conservative and Respectable SAE. For instance, when it occurs initially in stressed syllables in words like "house", it is deleted in Extreme SAE.[2]

- Conservative SAE is completely non-rhotic like Received Pronunciation, while Respectable SAE has sporadic moments of rhoticity. These rhotic moments generally occur in /r/-final words. More frequent rhoticity is a marker of Extreme SAE.[2]

- Unaspirated voiceless plosives (like /p/, /t/, and /k/) in stressed word-initial environments.[6]

- Yod-assimilation: tune and dune tend to be realised as [t͡ʃʉːn] and [d͡ʒʉːn], instead of the Received Pronunciation [tjuːn] and [djuːn].[6]

Lexicon

History of SAE Dictionaries

In 1913, Charles Pettman created the first South African English dictionary, entitled Africanderisms. This work sought to identify Afrikaans terms that were emerging in the English language in South Africa.[7] In 1924, the Oxford University Press published its first version of a South African English dictionary, The South African Pocket Oxford Dictionary. Subsequent editions of this dictionary have tried to take a "broad editorial approach" in including vocabulary terms native to South Africa, though the extent of this inclusion has been contested.[7] Rhodes University (South Africa) and Oxford University (Great Britain) worked together to produce the 1978 Dictionary of South African English, which adopted a more conservative approach in its inclusion of terms. This dictionary did include, for the first time, what the dictionary writers deemed "the jargon of townships", or vocabulary terms found in Black journalism and literary circles.[7] Dictionaries specialising in scientific jargon, such as the common names of South African plants, also emerged in the twentieth century. However, these works still often relied on Latin terminology and European pronunciation systems.[7] As of 1992, Rajend Mesthrie had produced the only available dictionary of South African Indian English.[7]

Vocabulary

SAE includes lexical items borrowed from other South African Languages. The following list provides a sample of some of these terms:

- braai (barbecue) from Afrikaans[6]

- impimpi (police informant)[4]

- indaba (conference; meeting) from Zulu[6]

- kwela-kwela (taxi or police pick-up van)[4]

- madumbies (a type of edible root) found in Natal

- mama (term of address for a senior woman)[4]

- mbaqanga (type of music)[4]

- morabaraba (board game)[4]

- sgebengu (criminal) found in IsiXhosa and IsiZulu speaking areas[4]

- skebereshe (a loose woman) found in Gauteng

- y'all (the contraction of "you all") for second person plural pronouns in ISAE[6]

British Lexical Items

SAE also contains several lexical items that demonstrate the British influence on this variety:

Expressions

A range of SAE expressions have been borrowed from other South African languages, or are uniquely used in this variety of English. Some common expressions include:

- The borrowed Afrikaans interjection ag, meaning "oh!", as in, "Ag, go away man"! (Equivalent to German "ach"). SAE uses a number of discourse markers from Afrikaans in colloquial speech.[6]

- The expression to come with, common especially among Afrikaans people, as in "are they coming with?"[8] This is influenced by the Afrikaans phrase hulle kom saam, literally "they come together", with saam being misinterpreted as with.[9] In Afrikaans, saamkom is a separable verb, similar to meekomen in Dutch and mitkommen in German, which is translated into English as "to come along".[10] "Come with?" is also encountered in areas of the Upper Midwest of the United States, which had a large number of Scandinavian, Dutch and German immigrants, who, when speaking English, translated equivalent phrases directly from their own languages.[11]

- The use of the "strong obligative modal" must as a synonym for the polite should/shall. "Must" has "much less social impact" in SAE than in other varieties.[6]

- Now-now, as in "I'll do it now-now". Likely borrowed from the Afrikaans nou-nou, this expression describes a time later than that referenced in the phrase "I'll do it now".[6]

- A large amount of slang comes from British origin, such as "naff" (boring, dull or plain).

Demographics

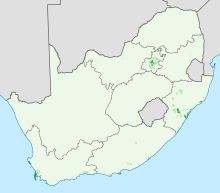

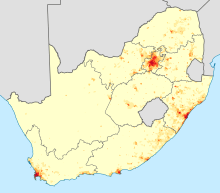

The South African National Census of 2011 found a total of 4,892,623 speakers of English as a first language,[12]:23 making up 9.6% of the national population.[12]:25 The provinces with significant English-speaking populations were the Western Cape (20.2% of the provincial population), Gauteng (13.3%) and KwaZulu-Natal (13.2%).[12]:25

English was spoken across all ethnic groups in South Africa. The breakdown of English-speakers according to the conventional racial classifications used by Statistics South Africa is described in the following table.

| Population group | English-speakers[12]:26 | % of population group[12]:27 | % of total English-speakers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Black African | 1,167,913 | 2.9 | 23.9 |

| Coloured | 945,847 | 20.8 | 19.3 |

| Indian or Asian | 1,094,317 | 86.1 | 22.4 |

| White | 1,603,575 | 35.9 | 32.8 |

| Other | 80,971 | 29.5 | 1.7 |

| Total | 4,892,623 | 9.6 | 100.0 |

Examples of South African accents

The following examples of South African accents were obtained from George Mason University:

- Native English: Male (Cape Town, South Africa)

- Native English: Female (Cape Town, South Africa)

- Native English: Male (Port Elizabeth, South Africa)

- Native English: Male (Nigel, South Africa)

See also

- List of English words of Afrikaans origin

- List of lexical differences in South African English

- List of South African slang words

- Standard written English

- Regional accents of English

References

-

en-ZAAfrikaans: Suid Afrikaans Engels is the language code for South African English, as defined by ISO standards (see ISO 639-1 and ISO 3166-1 alpha-2) and Internet standards (see IETF language tag). - Mesthrie, Rajend, ed. (2002). Language in South Africa. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521791052. OCLC 56218975.

- Mesthrie, R. (2006). "South Africa: Language Situation". Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics. pp. 539–542. doi:10.1016/b0-08-044854-2/01664-3. ISBN 9780080448541.

- De Klerk, Vivian; Gough, David (2002). Language in South Africa. pp. 356–378. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511486692.019. ISBN 9780511486692.

- Kortmann, Bernd; Schneider, Edgar W., eds. (2004). A Handbook of Varieties of English. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-017532-5.

- Bekker, Ian (1 January 2012). "The story of South African English: A brief linguistic overview". International Journal of Language, Translation and Intercultural Communication. 1 (0): 139–150. doi:10.12681/ijltic.16. ISSN 2241-7214.

- Taylor, Tim (1994). "Review of A Lexicon of South African Indian English". Anthropological Linguistics. 36 (4): 521–524. JSTOR 30028394.

- Mesthrie, Rajend, ed. (2008). Africa, South and Southeast Asia. Mouton de Gruyter. p. 475. ISBN 9783110196382.

- A handbook of varieties of English: a multimedia reference tool. Morphology and syntax, Volume 2, Bernd Kortmann, Mouton de Gruyter, 2004, page 951

- Pharos Tweetalige skoolwoordeboek/Pharos Bilingual school dictionary Archived 19 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Pharos Dictionaries, Pharos, 2014

- What's with 'come with'?, Chicago Tribune, 8 December 2010

- Census 2011: Census in brief (PDF). Pretoria: Statistics South Africa. 2012. ISBN 9780621413885. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 May 2015.

Bibliography

- de Gruyter, Walter (2008). Africa, South and Southeast Asia (PhD).

- Lass, Roger (2002), "South African English", in Mesthrie, Rajend (ed.), Language in South Africa, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521791052

Further reading

- Bekker, Ian (2012), "The story of South African English: A brief linguistic overview", International Journal of Language, Translation and Intercultural Communication, 1, doi:10.12681/ijltic.16, archived from the original on 31 October 2015, retrieved 21 August 2015

- Branford, William (1994), "9: English in South Africa", in Burchfield, Robert (ed.), The Cambridge History of the English Language, 5: English in Britain and Overseas: Origins and Development, Cambridge University Press, pp. 430–496, ISBN 0-521-26478-2

- De Klerk, Vivian, ed. (1996), Focus on South Africa, John Benjamins Publishing, ISBN 90-272-4873-7

- Lanham, Len W. (1979), The Standard in South African English and Its Social History, Heidelberg: Julius Groos Verlag, ISBN 3-87276-210-9

External links

- English Academy of South Africa

- Picard, Brig (Dr) J. H, SM, MM. "English for the South African Armed Forces" at the Wayback Machine (archived 22 June 2008)

- Zimbabwean Slang Dictionary

- "Surfrikan", South African surfing slang

- The influence of Afrikaans on SA English (in Dutch)

- The Expat Portal RSA Slang

- Several Samples of The Dialect

Countries.png)