Banat

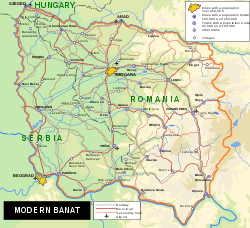

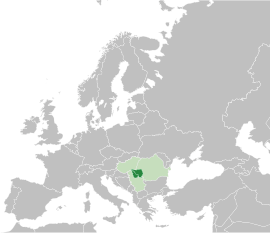

The Banat (UK: /ˈbænɪt, ˈbɑːn-/, US: /bɑːˈnɑːt/)[1] is a geographical and historical region straddling between Central and Eastern Europe that is currently divided among three countries: the eastern part lies in western Romania (the counties of Timiș, Caraș-Severin, Arad south of the Mureș river, and the western part of Mehedinți); the western part in northeastern Serbia (mostly included in Vojvodina, except a small part included in the Belgrade Region); and a small northern part lies within southeastern Hungary (Csongrád-Csanád County).[2][3][4][5][6]

Banat | |

|---|---|

Historical region | |

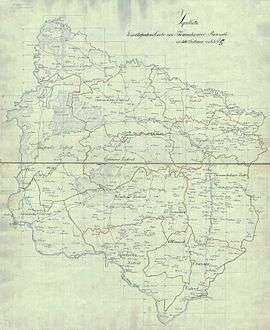

Map of the Banat region | |

| Coordinates: 45.7000°N 20.9000°E | |

| Country | |

| Largest city | Timișoara |

| Area | |

| • Total | 27,104 km2 (10,465 sq mi) |

| Population (2017 est) | |

| • Total | 979,119 |

| • Density | 36/km2 (94/sq mi) |

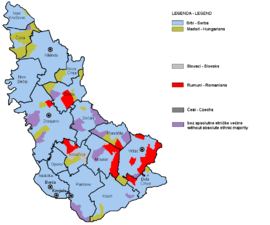

The region's historical ethnic diversity was severely affected by the events of World War II, and today Banat is overwhelmingly populated by ethnic Romanians, Serbs and Hungarians but small populations of other ethnic groups also live in the region and nearly all are citizens of either Serbia, Romania or Hungary.

Names

During the Middle Ages, the term "banate" was designating a frontier province led by a military governor who was called ban. Such provinces existed mainly in South Slavic, Hungarian and Romanian lands. In South Slavic and other regional languages, terms for "banate" were: Serbian – бановина / banovina, Hungarian – bánság, Romanian – banat and Latin – banatus.

At the time of the medieval Hungarian kingdom, the territory of modern-day Banat appeared in written sources as "Temesköz" (first mentioned in 1374).[7] The Hungarian name mainly referred to the lowland areas between the Mureş, Tisza and Danube Rivers.[7][8] Its Ottoman name was "Eyalet of Temeşvar" (later "Eyalet of Yanova"). During the Turkish occupation, the territory of Temesköz (Banat) was also called "Rascia" ("the country of the Serbs", 1577).[9]

In the early modern period, there were two banates that partially or entirely included the territory of what is referred to in the current era as Banat: the Banate of Lugoj and Caransebeș in 16th and 17th century and the Banat of Temeswar or Banat of Temes in 18th and 19th centuries. The word "Banat" without any other qualification, typically refers to the historical Banat of Temeswar, which acquired this title after the 1718 Treaty of Passarowitz. The name was also used from 1941 to 1944, during Axis occupation, for the short-lived political entity (see: Banat (1941–44)), which covered only today's Serbian part of the historical Banat.

The name Banat is similar in different languages of the region; Romanian: Banat, Serbo-Croatian: Banat / Банат (pronounced [bǎnaːt]), Hungarian: Bánát or Bánság, Bulgarian: Банат, German: Banat, Ukrainian: Банат, Turkish: Banat, Slovak: Banát, Czech: Banát, Greek: Βάνατον, Vànaton. Some of these languages would also have other terms, from their own frame of reference, to describe this historical and geographic region.

Geography

The Banat is defined as the part of the Pannonian Basin bordered by the River Danube to the south, the River Tisa to the west, the River Mureș to the north, and the Southern Carpathian Mountains to the east. The total area of the region is 28,526 km2 (11,014 sq mi).[10] Its historical capital was Timișoara, now in Timiș County in Romania.

The territory of the Banat is presently part of the Romanian counties Timiș, Caraș-Severin, Arad and Mehedinți; the Serbian autonomous province of Vojvodina and Belgrade City District; and the Hungarian Csongrád-Csanád County.

The Romanian Banat, with an area of 18,966 km2 (7,323 sq mi),[10] is mountainous in the south and southeast, while in the north, west and south-west it is flat and in some places marshy. The climate, except in the marshy parts, is generally healthy. Wheat, barley, oats, rye, maize, flax, hemp and tobacco are grown in large quantities, and the products of the vineyards are of a good quality. Game is plentiful and the rivers swarm with fish. The mineral wealth is great, including copper, tin, lead, zinc, iron and especially coal. Amongst its numerous mineral springs, the most important are those of Mehadia, with sulphurous waters, which were already known in the Roman period as the Termae Herculis (Băile Herculane). The present "Banat Region" of Romania includes some areas that are mountainous and were not part of the historical Banat or of the Pannonian plain.

In Serbia, the Banat is mostly plains. Wheat, barley, oats, rye, maize, hemp and sunflower are grown, and mineral wealth consists of oil and natural gas. A popular tourist destination in the Banat is Deliblatska Peščara. There are also several ethnic minorities in the region, including Hungarians (10.21% of the population), Romanians, Slovaks, Bulgarians, Macedonians, Roma people, and others.

History

| History of Banat |

|---|

|

| Historical Banat |

|

| Modern Romanian Banat |

| Modern Serbian Banat |

| Modern Hungarian Banat |

Prehistory and antiquity

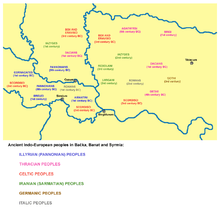

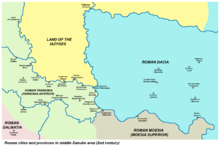

The first known inhabitants of present-day Banat were the Neolithic populations. In the 4th century BC, Celtic tribes settled in this area. Various Hallstatt and La Tène objects were found in this area. The most important tribes were the Scordisci and the Taurisci. The Scordisci, who formed a powerful state even minted their own coins, imitating the Macedonian tetradrachm. The Scordisci subdued as all the other tribes in the region to the getic ruler Burebista, therefore their region was part of the Dacian kingdom under Burebista in the first century BC, but the balance of power in the area partially changed during the campaigns of Augustus. At the beginning of the 2nd century A.D., Trajan led two wars against the Dacians: the campaigns of 101–102, and 105–106. Eventually, the territory of Banat fell under Roman rule. It became an important link between Dacia province and the other parts of the Empire. Roman rule had a significant impact: castra and guard stations were established and roads and public buildings built. The public bath establishments of Ad Aquas Herculis, modern-day Băile Herculane were also established. Some of the important Roman settlements in Banat were: Arcidava (today Vărădia), Centum Putea (today Surducu Mare), Berzobis (today Berzovia), Tibiscum (today Jupa), Agnaviae (today Zăvoi), Ad Pannonios (today Teregova), Praetorium (today Mehadia), and Dierna (today Orșova).

In 273 A.D. Emperor Aurelian withdrew the Roman Army from Dacia. The area fell into the hands of foederati such as the Sarmatians (Iazyges, Roxolani, Limigantes) and later the Goths, who also took control of other parts of Dacia.

Ancient Indo-European peoples in Banat

Ancient Indo-European peoples in Banat Ancient Roman cities in Banat

Ancient Roman cities in Banat

Migration Period and Early Middle Ages

The Goths were forced out by the Huns, who organized their ruling center in the Pannonian Basin (the Pannonian Plain), an area that included the northwestern part of today's Banat. After the death of Attila, the Hunnic empire disintegrated in days. The previously subjected Gepids formed a new kingdom in the area, only to be defeated 100 years later by the Avars.

One governing center of the Avars was formed in the region, which played an important role in the Avar–Byzantine wars. An inscription on one of the vessels from the Treasure of Sânnicolau Mare (which origin is disputed) recorded names of two local rulers, Butaul and Buyla, who bore Slavic ruling titles of župan. The Avar rule over the area lasted until the 9th century, until Charlemagne's campaigns. The Banat region became part of the First Bulgarian Empire a few decades later. Archaeological evidence shows the Avars and Gepids lived here until the middle of the 10th century. The Avar rule had triggered considerable Slavic migration to the southern Pannonian plain and to the Balkans.

In 895, the Hungarians living in Etelköz entered the Byzantine-Bulgarian war as allies of Byzantium, and defeated the Bulgars. Because of this, the Bulgarians allied with the Pechenegs, who attacked the Hungarian settlements. This led to the process of what is known as the Hungarian conquest of the Pannonian basin, referred to by them as "hometaking" (honfoglalás) in Hungarian. This also resulted in the loss of part of the territories north of the Danube for the Bulgarian Empire.

According to Gesta Hungarorum chronicle, a local ruler known as Glad ruled over the Banat and his army was formed by Vlachs, Bulgarians, and Cumans[11] Ahtum was another early-11th-century ruler in the territory now known as Banat. His primary source is the Long Life of Saint Gerard, a 14th-century hagiography. Chanadinus, Ahtum's former commander-in-chief, defeated and killed Ahtum, occupying his realm.[11]

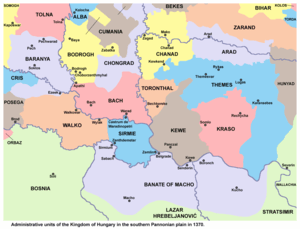

Hungarian administration (11th–16th centuries)

Banat was administered by the First Bulgarian Empire from the 9th to the 11th century, but that control gradually migrated to the Kingdom of Hungary which administered it from the 11th century up until 1552, when the region of Temesvár (today Timișoara) was captured by the Ottoman Empire. The area of the Timiș river was not the land of the Hungarian royal tribe. When nomadic Hungarians came to Transylvania there was no direct Bulgarian political rule there.[12] In the eastern part of the Carpathian basin the Byzantine rite became more influential after Ajtony's (Latin: Ahtum) conversion to Christianity. This was halted with the establishment of the Kingdom of Hungary. István I reasserted dominance over the last local leader, Ajtony. He was a semi-independent ruler of Banat and an Orthodox Christian who constructed a Byzantine monastery at Morisena. His vassal Csanád defeated him by the will of King Stephen I of Hungary. The territory of the modern Banat did not form a separate territorial unit in medieval Kingdom of Hungary, it was an integral part of it. The territory was shared by Krassó, Keve, Temes, Csanád, Arad and Torontál Counties.

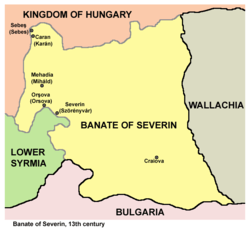

In 1233, under the Kingdom of Hungary administration, the Banate of Severin, a military frontier area was formed, including some eastern parts of the modern Banat. In the 14th century, the region became of priority concern to the Kingdom, as the southern border of the Banat was the most important defensive line against Ottoman expansion from the Southeast.

Ottoman administration (1552–1716)

The Ottoman Empire took over the area and incorporated the Banat in 1552. It was absorbed as an Ottoman eyalet (province) named the Eyalet of Temeşvar. The Banat region was mainly populated by Rascians (Serbs) in the west and Vlachs (Romanians) in the east; thus, in some historical sources it was referred to as Rascia and in others Wallachia. Numerous Ottoman Muslims settled in the area, living mostly in the cities and associated with trade and administration.

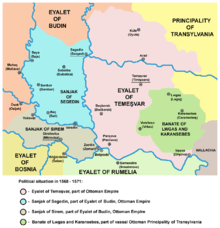

Not all of the Banat fell immediately under Turkish rule. Eastern regions around Lugoj and Caransebeș came under the rule of Princes of Transylvania. In that area, a new banate was formed, known as the Banate of Lugoj and Caransebeș.

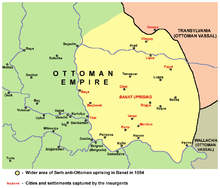

In the spring of 1594, shortly after the beginning of Austro-Turkish War (1593-1606), Serbian Christians in Eyalet of Temeşvar started an Uprising against Turkish rule. The local Romanians also participated in this uprising. At first, rebels were successful. They took the city of Vršac and various other towns in Banat and started negotiations with Prince of Transylvania. One of the leaders of the uprising was local Serbian Orthodox Bishop Theodore.[13]

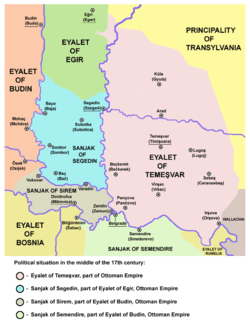

In the middle of the 17th century, the territory of Banate of Lugoj and Caransebeș finally fell under Turkish rule and was incorporated into Eyalet of Temeşvar.

During Austro-Turkish War (1683-1699), local Serbian uprisings broke out in various parts of Eyalet of Temeşvar. Austrian armies and Serbian militia tried to drive out sultans army from the province, but Turks succeeded in holding the fort of Temesvár. In 1689, Serbian patriarch Arsenije III sided with Austrians. His jurisdiction (including the province) was officially recognized by the charters of emperor Leopold I in 1690, 1691 and 1695. Under the Treaty of Karlowitz (1699), northern parts of the Eyalet of Temeşvar were incorporated into the Habsburg Monarchy, but the territory of Banat remained under Turkish rule.

Jurisdiction of Serbian Patriarchate in 16th and 17th century

Jurisdiction of Serbian Patriarchate in 16th and 17th century Eyalet of Temeşvar and Banate of Lugoj and Caransebeș in 1568

Eyalet of Temeşvar and Banate of Lugoj and Caransebeș in 1568 Uprising in Banat in 1594

Uprising in Banat in 1594 Eyalet of Temeşvar in the middle of the 17th century

Eyalet of Temeşvar in the middle of the 17th century Eyalet of Temeşvar and the surrounding regions in 1683

Eyalet of Temeşvar and the surrounding regions in 1683 Eyalet of Temeşvar, from 1699 to 1716

Eyalet of Temeşvar, from 1699 to 1716

Habsburg administration (1716–1867)

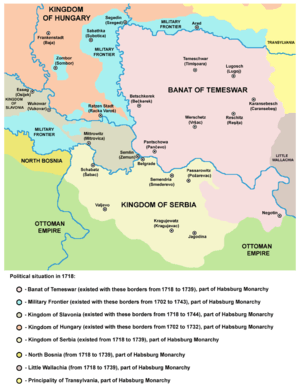

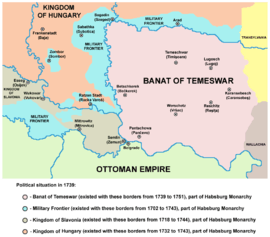

At the beginning of the next Austro-Turkish War (1716–1718), Prince Eugene of Savoy took the Banat region from the Turks. After the Treaty of Passarowitz (1718), the region became a province of the Habsburg Monarchy. It was not incorporated into the Kingdom of Hungary. Special provincial administration was established, centered in Temesvár.

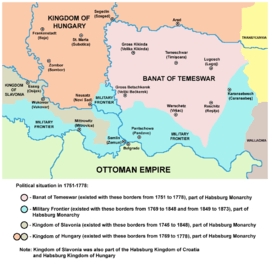

In 1738, over 50 Romanian villages from Serbia and Banat were destroyed and dwellers murdered by Austrians and Serb militia during a revolt of Romanians.[14] Also governor of the province was not given the title of "ban", the region became known as the Banate of Temes or Banat of Temeswar. It remained a separate province within the Habsburg Monarchy and under military administration until 1751, when Empress Maria Theresa of Austria reorganized the province, dividing it between military and civil administration. The Banat of Temeswar province was abolished in 1778, when civilian part of the region was incorporated into the Kingdom of Hungary and divided into counties. The southern part of the Banat region remained within the Military Frontier (Banat Krajina) until the Frontier was abolished in 1871.

During the Ottoman rule, parts of Banat had a low population density due to years of warfare, and some local residents also lost their lives during Habsburg-Ottoman wars and Prince Eugene of Savoy's conquest. Much of the area had reverted to nearly uninhabited marsh, heath and forest. Count Claudius Mercy (1666–1734), who was appointed governor of the Banat of Temeswar in 1720, took numerous measures for the regeneration of the Banat. He recruited German artisans and especially farmers from Bavaria and other southern areas as colonists, allowing them privileges such as keeping their language and religion in their settlements. Farmers brought their families and belongings on rafts down the Danube River, and were encouraged to restore farming in the area. They cleared the marshes near the Danube and Tisa rivers, helped build roads and canals, and re-established agriculture. Trade was also encouraged.[15]

Maria Theresa also took a direct interest in the Banat; she colonized the region with large numbers of German farmers, who were admired for their agricultural skills. She encouraged the exploitation of the mineral wealth of the country, and generally developed the measures that were introduced by Count Mercy.[15] German settlers arrived from Swabia, Alsace and Bavaria, as did German-speaking colonists from Austria. Many settlements in the eastern Banat were developed by Germans and had ethnic-German majorities. The ethnic Germans in the Banat region became known as the Danube Swabians, or Donauschwaben. After years of separation from their original German provinces, their language was markedly different, preserving historic characteristics.

Similarly, a minority coming from French-speaking or linguistically mixed communes in Lorraine maintained the French language for several generations, and developed a specific ethnic identity, later known as Banat French, Français du Banat.[16]

In 1779, the Banat region was incorporated into the Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary, and the three counties of Torontal, Temes and Karasch were created. In 1848, after the May Assembly, the western Banat became part of the Serbian Vojvodina, a Serbian autonomous region within the Habsburg Monarchy. During the Revolutions of 1848–1849, the Banat was respectively held by Serbian and Hungarian troops.

After the Revolution of 1848–1849, the Banat (together with Syrmia and Bačka) was designated as a separate Austrian crownland known as the Voivodeship of Serbia and Temes Banat. In 1860 this province was abolished and most of its territory was incorporated into the Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary.

The Serbian Banat (Western Banat) was part of Serbian Vojvodina (1848–1849) and part of the Voivodeship of Serbia and Temes Banat (1849–1860). After 1860, later Serbian Banat was part of Torontal and Temes counties of Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary. The center of Torontal county was Großbetschkerek (Hungarian: Nagybecskerek, Serbian: Veliki Bečkerek), the current Zrenjanin.

Hungarian administration (1867–1918)

In 1867, after the Austro-Hungarian compromise the territory returned again to Hungarian administration. After 1871, the former Military Frontier, located in southern parts of the Banat, came under civil administration and was incorporated into the Banat counties. Krassó and Szörény were united into Krassó-Szörény in 1881.

Proclaimed borders of Serbian Vojvodina in 1848 (including Western Banat)

Proclaimed borders of Serbian Vojvodina in 1848 (including Western Banat).png) Voivodeship of Serbia and Temes Banat (1849–1860)

Voivodeship of Serbia and Temes Banat (1849–1860)

The Banat Question at the end of First World War

In 1918, the Banat Republic was proclaimed in Timișoara in October, and the government of Hungary recognized its independence. However, it was short-lived. After just two weeks, Serbian troops invaded the region and took control. From November 1918 to March 1919, western and central parts of Banat were governed by Serbian administration from Novi Sad, as part of the Banat, Bačka and Baranja province of the Kingdom of Serbia and newly formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (which was later renamed as Yugoslavia).

In the wake of the Declaration of Union of Transylvania with Romania on December 1, 1918 and the Declaration of Unification of Banat, Bačka and Baranja with Serbia on November 25, 1918, most of the Banat was (in 1919) divided between Romania (Krassó-Szörény completely, two-thirds of Temes, and a small part of Torontál) and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (most of Torontál, and one-third of Temes). A small area near Szeged was assigned to the newly independent Hungary. These borders were confirmed by the 1919 Treaty of Versailles and the 1920 Treaty of Trianon.

At the dissolution of Austria-Hungary, the delegates of the Romanian and some German communities voted for union with Romania;[17][18] the delegates of the Serbian, Bunjevac and other Slavic and non-Slavic communities (including some Germans) voted for union with Serbia; while the Hungarian minority remained loyal to the government in Budapest. Besides these declarations, no other plebiscite was held.

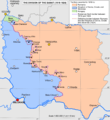

Self-proclaimed Banat Republic in 1918

Self-proclaimed Banat Republic in 1918 Situation around Banat in 1918

Situation around Banat in 1918 Situation around Banat in 1919–1921

Situation around Banat in 1919–1921 Division of Banat in 1919–1923

Division of Banat in 1919–1923

Romanian Banat since the First World War

.svg.png)

In 1938, the counties of Timiș-Torontal, Caraș, Severin, Arad and Hunedoara were joined to form ținutul Timiș, which roughly encompassed the area typically called Banat in Romania.

On 6 September 1950, the province was replaced by the Timișoara Region (formed by the present-day counties of Timiș and Caraș-Severin). In 1956, the southern half of the existing Arad Region was incorporated to the Timișoara Region. In December 1960, the Timișoara Region was renamed the Banat Region.

On 17 February 1968, a new territorial division was made and today's Timiș, Caraș-Severin and Arad counties were formed.

Since 1998, Romania has been divided into eight development regions, acting as divisions that coordinate and implement regional development. The Vest development region is composed of four counties: Arad, Timiș, Hunedoara and Caraș-Severin; thus it has almost same borders as the Timiș Province (ținutul Timiș) of 1938. The Vest development region is also a part of the Danube-Criș-Mureș-Tisa Euroregion.

Ethnic minorities in the region include Hungarians (5.6% of the population), Serbs, Croats (Krashovans), Bulgarians, Ukrainians, and others. The area has been inhabited by Serbs since medieval times, with the largest numbers of inhabitants in 18th century. The main areas of Serb settlements were along the Mureş in Sânnicolau Mare, Cena, Sânpetru Mare and Recaş. Croats are settled in Caraşova and the neighbouring villages of Anina and Reşiţa. Albanians who arrived in 1740 were assimilated by the majority Caraşoveni. At the beginning of the 19th century, the villages of Ceneiul Croat and Checea Croată were established which are connected with Croatian presence in that area.[19]

Serbian Banat since the First World War

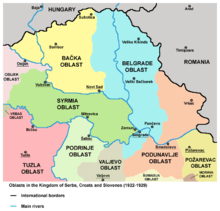

The region was claimed by the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes between 1918 and 1922 (as the province of Banat, Bačka and Baranja between 1918–1919]) and from 1922 to 1929 it was divided between Belgrade oblast and Podunavlje oblast. In 1929, most of the region was incorporated into the Danube Banovina (Danubian Banat), a province of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, while the city of Pančevo was incorporated into self-governed Belgrade district.

During World War II, the Axis Powers occupied this area and partitioned it. Nazi Germany had been intent on expanding into eastern Europe to incorporate what it called the Volksdeutsche, people of ethnic German descent. They established the political entity known as Banat in 1941. It included only the western part of the historical Banat region, which was formerly part of Yugoslavia. It was formally under the control of the Serbian puppet Government of National Salvation in Belgrade led by Milan Nedić. It theoretically had limited jurisdiction over all of the territory under German Military Administration in Serbia, but in practice the local minority of ethnic Germans (Danube Swabians or Shwoveh) held the political power within the Banat. The regional civilian commissioner was Josef Lapp. The head of the ethnic German group was Sepp Janko. Following the ousting of Axis forces in 1944, this German-ruled region was dissolved. As a consequence, much of the local Germans fled from the region together with defeated German army in 1944. Most of its territory was included in the Vojvodina, one of the two autonomous provinces of Serbia within the new SFR Yugoslavia. Following WWII, most ethnic Germans were expelled from the Banat and eastern Europe. Those Germans who remained in the country were sent to prison camps run by the new communist authorities. After prison camps were dissolved (in 1948), most of the remaining German population left Serbia because of economic reasons. Many went to Germany; others emigrated to western Europe and the United States.

Since 1944–1945, the Serbian Banat (together with Bačka and Syrmia), has been part of the Serbian Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, first as part of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and then as part of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and Serbia and Montenegro. Since 2006, it has been part of an independent Serbia.

The districts of Serbia in Banat are: North Banat okrug (which also includes municipalities of Ada, Senta and Kanjiža, which are situated in the region of Bačka), Central Banat okrug, and South Banat okrug.

Serbian Banat also includes the area known as Pančevački Rit, which belongs to the Belgrade municipality of Palilula.

See also: Geographical regions in Serbia

Hungarian Banat since the First World War

The Hungarian Banat consists of a small northern part of the region, which is part of the Csongrád-Csanád County of Hungary and is made up of 7 villages and the district of Szeged, Újszeged. The Hungarian part of Banat used to be the northernmost region of the Torontál County in the Kingdom of Hungary. In addition to the Hungarian population, there is a small minority of Serbs (e.g. in Deszk, Szőreg).

Demographics

The whole Banat

1660–1666

In 1660–1666, Serbs lived in western (flat) part of the Banat, while Romanians lived in the eastern (mountainous) part.[20]

1743–1753

In 1743–1753, ethnic composition of Banat looked as follows:[21]

- Three eastern districts had a Romanian population: Lugoj, Caransebeș, and Orșova.

- Three western districts had a Serbian population: Veliki Bečkerek, Pančevo, and Velika Kikinda.

- Six central districts had a mixed Serb-Romanian population: Timișoara, Lipova, Vršac, Nova Palanka, Ciacova, and Cenad.

Ethnic Hungarians were almost totally absent from the region in the first half of the 18th century.[22] They were considered politically unreliable, but in 1730 some Catholic Hungarians were allowed to settle down in the Banat.[23]

1774

According to 1774 data, the population of the Banat of Temeswar numbered 375,740 people and was composed of:[24]

- 220,000 (58.55%) Romanians

- 100,000 (26.61%) Serbs and Greeks

- 53,000 (14.11%) Germans

- 2,400 (0.64%) Hungarians and Bulgarians

- 340 (0.09%) Jews

1840

Banat had in 1840 a population of over a million which included:[23]

- 570,000 (55.34%) Romanians

- 200,000 (19.42%) Germans

- 200,000 (19.42%) Serbs

- 60,000 (5.83%) Hungarians

1900

In 1900, the population of Banat numbered 1,431,329 people, including:[25]

- 578,789 (40.4%) Romanians

- 362,487 (25.3%) Germans

- 251,938 (17.6%) Serbs

- 170,124 (11.9%) Hungarians

1910

According to the 1910 census, the population of the Banat region (counties of Torontál, Temes and Krassó-Szörény) numbered 1,582,133 people, including:[26][27][28] (*)

- 592,049 (37.42%) Romanians

- 387,545 (24.50%) Germans

- 284,329 (17.97%) Serbs

- 242,152 (15.31%) Hungarians

- smaller numbers of other ethnic groups such as the Czechs, Slovaks, Croats, Rusyns, Ukrainians, Bulgarians, etc.

(*) Note: according to the 1910 census, the population of Romanian Banat included 52.6% Romanians, 25.6% Germans, 12.2% Hungarians, and 4.9% Serbs, while population of Serbian Banat included 40.53% Serbs, 22.14% Germans, 19.18% Hungarians, 12.94% Romanians, and 2.86% Slovaks. In Serbia the majority of the Banat Swabian or Shwovish population fled from the region together with the defeated German army in the Fall of 1944, as one can see in the population Table below, where the German-speaking Shwovish population dropped from about 120,000 in 1931 to about 17,000 in 1948. Those who remained in the country were sent to prison camps run by the new communist authorities, where many died from hunger, disease and cold, but many also escaped. After the prison camps were dissolved (in 1948), most of the remaining German population left Serbia and Yugoslavia because of economic reasons. Their flight was mainly a consequence of wartime events and Axis occupation of Yugoslavia, but partly also a consequence of the economic situation in the post-war years. In Romania ethnic Germans mostly emigrated after 1989 for economic reasons.

1930

Distribution of ethnicities in Banat from 1930:[29]

- 511,100 (54,4%) Romanians

- 223,200 (23,7%) Germans

- 97,800 (10,4%) Hungarians

- 40,500 (4,3%) Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

Population table

The historical population of the Banat region in different time periods:

| Year | Total |

|---|---|

| 1717 | 85,166 |

| 1743 | 125,000 |

| 1753 | 210,992 |

| 1774 | 375,740 |

| 1797 | 667,912 |

| 1900 | 1,431,329 |

| 1910 | 1,582,133 |

Romanian Banat

The historical population of the Romanian Banat (the Timiș,[30][31] and Caraș-Severin,[32][33] counties)[34] was as following:

| Year | Total | Romanians | Hungarians | Germans | Serbs | Roma |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 744,367 | 426,368 (57.3%) | 37,586 (5.0%) | 202,698 (27.2%) | 46,983 (6.3%) | n/a |

| 1890 | 812,799 | 446,816 (55.0%) | 50,899 (6.3%) | 233,006 (29.9%) | 41,356 (5.1%) | n/a |

| 1900 | 871,598 | 468,508 (53.8%) | 78,656 (9.0%) | 243,582 (27.9%) | 41,960 (4.8%) | n/a |

| 1910 | 902,210 | 474,787 (52.6%) | 109,873 (12.2%) | 231,391 (25.6%) | 44,598 (4.9%) | n/a |

| 1920 | 822,639 | 450,817 (54.8%) | 79,955 (9.7%) | 208,774 (25.4%) | n/a | n/a |

| 1930 | 878,877 | 473,781 (53.9%) | 91,421 (10.4%) | 215,031 (24.5%) | 37,113 (4.2%) | 16,471 (1.9%) |

| 1941 | 898,262 | 505,448 (56.3%) | 80,575 (9.0%) | 213,840 (23.8%) | n/a | n/a |

| 1956 | 896,668 | 589,369 (65.7%) | 85,790 (9.6%) | 137,697 (15.4%) | 40,018 (4.5%) | 9,309 (1.0%) |

| 1966 | 966,322 | 674,062 (69.8%) | 85,358 (8.8%) | 133,197 (13.8%) | 38,535 (4.0%) | 6,769 (0.7%) |

| 1977 | 1,082,461 | 796,007 (73.5%) | 86,763 (8.0%) | 119,972 (11.1%) | 29,514 (2.7%) | 15,755 (1.5%) |

| 1992 | 1,076,380 | 886,958 (82.4%) | 70,742 (6.6%) | 38,658 (3.6%) | 25,029 (2.3%) | 22,612 (2.1%) |

| 2002 | 1,011,145 | 859,690 (85.0%) | 56,380 (5.6%) | 20,323 (2.0%) | 19,355 (1.9%) | 23,998 (2.4%) |

| 2011 | 979,119 | 794,769 (81.2%) | 38,233 (3.9%) | 11,401 (1.2%) | 20,474 (2.1%) | 21,797 (2.2%) |

Serbian Banat

| Year | Total | Serbs | Hungarians | Germans | Romanians | Slovaks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 566,400 | 229,568 (40.5%) | 108,622 (19.2%) | 125,374 (22.1%) | 73,303 (12.9%) | 16,223 (2,9%) |

| 1921 | 559,096 | 235,148 (42.1%) | 98,463 (17.6%) | 126,519 (22.6%) | 66,433 (11,9%) | 17,595 (3,2%) |

| 1931 | 585,579 | 261,123 (44,6%) | 95,867 (16,4%) | 120,541 (20,6%) | 62,365 (10,7%) | 17,900 (2,1%) |

| 1948 | 601,626 | 358,067 (59,6%) | 110,446 (18,4%) | 17,522 (2,9%) | 55,678 (9,3%) | 20,685 (2,4%) |

| 1953 | 617,163 | 374,258 (60,6%) | 112,683 (18,4%) | n/a | 55,094 (8,9%) | 21,299 (3,4%) |

| 1961 | 655,868 | 423,837 (64,6%) | 111,944 (17,1%) | n/a | 54,447 (8,3%) | 22,306 (3,4%) |

| 1971 | 666,559 | 434,810 (65,2%) | 103,090 (15.5%) | n/a | 49,455 (7,4%) | 22,173 (3,3%) |

| 1981 | 672,884 | 424,765 (65,7%) | 90,445 (14,0%) | n/a | 43,474 (6,7%) | 21,392 (3,3%) |

| 1991 | 648,390 | 423,475 (65,1%) | 76,153 (11.7%) | n/a | 35,935 (5,5%) | 19,903 (3.1%) |

| 2002 | 665,397 | 477,890 (71.8%) | 63,047 (9.5%) | 908 (0,1%) | 27,661 (4,1%) | 17,994 (2,7%) |

Symbols

The traditional heraldic symbol of the Banat is a lion, which is nowadays present in both the coat of arms of Romania and the coat of arms of Vojvodina.

Cities

The largest cities in the Banat are:

Tourist spots

- Museum of Banat

- Huniade Castle

- Mühle House

- Cetate Synagogue

- Fabric Synagogue

- Iosefin Synagogue

- Timișoara Orthodox Cathedral

- St. George's Cathedral, Timișoara

- Millennium Church

- Sveti Đurađ monastery

- Theresia Bastion

- Capitoline Wolf Statue

- Cheile Nerei-Beușnița National Park

- Semenic-Cheile Carașului National Park

- Domogled-Valea Cernei National Park

Gallery

Timișoara

Timișoara

Lugoj

Lugoj Caransebeș

Caransebeș

References

- "Banat". Collins English Dictionary/Webster's New World College Dictionary.

- "Banat – NVBNT". nvbnt.wordpress.com (in Romanian). Retrieved 2017-05-06.

- "EXCLUSIV A fost conceput primul steag al Banatului: o cruce albă pe fundal verde". m.adevarul.ro. Retrieved 2017-05-06.

- SRL, SC Webforyou. "Sfântul Gheorghe – calendar intercultural". www.calendarintercultural.ro. Archived from the original on 2018-01-08. Retrieved 2017-05-06.

- Bălan, Titus. "Avem sau nu avem nevoie de un steag al Banatului?". www.banatulazi.ro (in Romanian). Retrieved 2017-05-06.

- Călin, Drd. Claudiu (2016). "Prezența călugărilor greci la Cenad în sec. al XI-lea și transferarea lor la Oroszlámos/Banatsko Aranđelovo. O pseudo-dispută". Morisena.

- "Temesköz". MAGYAR NÉPRAJZI LEXIKON (Hungarian Ethnographic Lexicon). Akademiai Kiado (1977–1982).

- "Temesköz". Magyar Katolikus Lexikon (Hungarian Catholic Lexicon).

- Pálffy, Géza (2001). "The Impact of the Ottoman rule on Hungary" (PDF). Hungarian Studies Review. XXVIII (1–2): 109–132. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- Aspecte geografice ale evoluției structurii etnice a populației Banatului

- Madgearu, Alexandru – Geneza și evoluția voievodatului bănățean din secolul al X-lea.(Origins and evolution of Banat duchy in the 19th century). Studii și Materiale de Istorie Medie, 16, 1998, p. 191-207

- Victor Spinei, The Romanians and the Turkic Nomads North of the Danube Delta from the Tenth to the Mid-Thirteenth Century (East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages), 450–1450, Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2009 p.59, ISBN 9789004175365,

- Ćirković 2004, p. 141-142.

- Picot, Emile, Les serbes de Hongrie, leur histoire, leurs privileges, leur église, leur état politique et social. Prague. Grégr & Dattel libraires éditeurs. 1873. p.113

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Smaranda Vultur, De l’Ouest à l’Est et de l’Est à l’Ouest : les avatars identitaires des Français du Banat, Texte presenté a la conférence d'histoire orale: Visibles mais pas nombreuses : les circulations migratoires roumaines, Paris, 2001

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on June 8, 2011. Retrieved January 13, 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-01-27. Retrieved 2011-01-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Remus Creţan, David Turnock et Jaco Woudstra: (2008) Identity and multiculturalism in the Romanian Banat p. 19;

- Dr. Dušan J. Popović, Srbi u Vojvodini, knjiga 2, Novi Sad, 1990.

- Dr. Dušan J. Popović (see above)

- Ethnic Geography of the Hungarian Minorities in the Carpathian Basin – By Károly Kocsis, Eszter Kocsisné Hodosi, page 140.

- Judy Batt, Kataryna Wolczuk. Region State and Identity in Central and Eastern Europe

- Miodrag Milin, Vekovima zajedno (iz istorije srpsko-rumunskih odnosa), Temišvar, 1995.

- Banatul.com – History and Information about Banat, Serbia and Banat, Romania Archived 2006-02-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Torontál County

- Temes County Archived March 9, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Krassó-Szörény County

- Remus Creţan, David Turnock et Jaco Woudstra: (2008) Identity and multiculturalism in the Romanian Banat p. 21;

- Ethnic composition of the Timiș County (1850–1992)

- Recensământ 2002, Census 2002: Timiș County Archived 2007-06-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Ethnic composition of the Caraș-Severin County (1850–1992)

- Recensământ 2002, Census 2002: Caraș-Severin County Archived June 26, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Populaţia după etnie la recensămintele din perioada 1930–2011 – judeţe". Retrieved 7 August 2018.

Sources

- Dušan Belča, Mala istorija Vršca, Vršac, 1997.

- Bocşan, Nicolae (2015). "Illyrian privileges and the Romanians from the Banat" (PDF). Banatica. 25: 243–258.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Milojko Brusin, Naša razgraničenja sa susedima 1919–1920, Novi Sad, 1998.

- Branislav Bukurov, Bačka, Banat i Srem, Novi Sad, 1978.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fodor, Pál; Dávid, Géza, eds. (2000). Ottomans, Hungarians, and Habsburgs in Central Europe: The Military Confines in the Era of Ottoman Conquest. BRILL. ISBN 9004119078.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ingrao, Charles; Samardžić, Nikola; Pešalj, Jovan, eds. (2011). The Peace of Passarowitz, 1718. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. ISBN 9781557535948.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Miodrag Milin, Vekovima zajedno (Iz istorije srpsko-rumunskih odnosa), Temišvar, 1995.

- Jovan M. Pejin, Iz prošlosti Kikinde, Kikinda, 2000.

- Pešalj, Jovan (2010). "Early 18th-Century Peacekeeping: How Habsburgs and Ottomans Resolved Several Border Disputes after Karlowitz". Empires and Peninsulas: Southeastern Europe between Karlowitz and the Peace of Adrianople, 1699–1829. Berlin: LIT Verlag. pp. 29–42. ISBN 9783643106117.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spinei, Victor (2009). The Romanians and the Turkic Nomads North of the Danube Delta from the Tenth to the Mid-Thirteenth Century. leiden and Boston: Brill.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Milan Tutorov, Mala Raška a u Banatu, istorika Zrenjanina i Banata, Zrenjanin, 1991.

- Josef Wolf, Entwicklung der ethnischen Struktur des Banats 1890–1992 (Atlas Ost- und Südosteuropa / Hrsg.: Österreichisches Ost- und Südosteuropa-Institut; 2: Bevölkerung; 8 = H/R/YU 1, Ungarn/Rumänien/Jugoslawien), Berlin – Stuttgart, 2004.

- Tiberiu Schatteles, EVREII DIN TIMISOARA IN PERSPECTIVA ISTORICA Editura "HASEFER" Bucuresti, 2013

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Banat. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Banat. |

- Banat social networking website

- banatul.com (in English and Romanian)

- backabanat.com (in Serbian)

- Development of Ethnic Structure in the Banat 1890 – 1992

- Regions Banat (in English, Romanian, French, and German)

- Návštěva Svaté Heleny, reportáž z expedice Roadtrip 2007 – návštěva Banátu (Svaté Heleny) (in Czech)

- Penka Peykovska, Írás-olvasástudás és analfabetizmus a többnemzetiségű Bánságban (in Hungarian)

- Smaranda Vultur, De l’Ouest à l’Est et de l’Est à l’Ouest : les avatars identitaires des Français du Banat (in French)

- Remembering Molidorf (in English, Romanian, French, and German)

- Family Books of the Banat (in English, Romanian, French, and German)

- Danube Swabian Resources (in English, Romanian, and German)

- Donauschwaben Villages Helping Hands Nonprofit (in English)

- Danube Swabians in Banat (in English)

- Stanko Trifunović (1997). "Slovenska naselja V-VIII veka u Bačkoj i Banatu". Novi Sad: Muzej Vojvodine.