Hermann Hesse

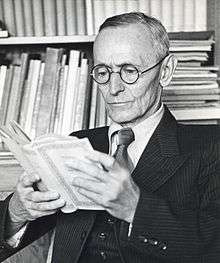

Hermann Karl Hesse (German: [ˈhɛʁ.man ˈhɛ.sə]] (![]()

Hermann Hesse | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 2 July 1877 Calw, Oberamt Calw, Schwarzwaldkreis, Kingdom of Württemberg, German Empire |

| Died | 9 August 1962 (aged 85) Montagnola, Ticino, Switzerland |

| Resting place | Cimitero di S. Abbondio Montagnola, Ticino |

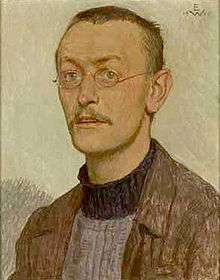

| Occupation | Novelist, short story author, essayist, poet, painter |

| Nationality | German, Swiss |

| Period | 1904–1953 |

| Genre | Fiction |

| Notable works | The Glass Bead Game Siddhartha Steppenwolf Narcissus and Goldmund Demian |

| Notable awards |

|

| Signature |  |

Life and work

Family background

Hermann Karl Hesse[1] was born on 2 July 1877 in the Black Forest town of Calw in Württemberg, German Empire. His grandparents served in India at a mission under the auspices of the Basel Mission, a Protestant Christian missionary society. His grandfather Hermann Gundert compiled the current grammar in Malayalam language, compiled a Malayalam-English dictionary, and also contributed to the work in translating the Bible to Malayalam.[2] Hesse's mother, Marie Gundert, was born at such a mission in India in 1842. In describing her own childhood, she said, "A happy child I was not..." As was usual among missionaries at the time, she was left behind in Europe at the age of four when her parents returned to India.[3]

Hesse's father, Johannes Hesse, the son of a doctor, was born in 1847 in Weissenstein, Governorate of Estonia in the Russian Empire (now Paide, Järva County, Estonia). Johannes Hesse belonged to the Baltic German minority in the Russian-ruled Baltic region: thus his son Hermann was at birth both a citizen of the German Empire and the Russian Empire.[4] Hermann had five siblings, but two of them died in infancy. In 1873, the Hesse family moved to Calw, where Johannes worked for the Calwer Verlagsverein, a publishing house specializing in theological texts and schoolbooks. Marie's father, Hermann Gundert (also the namesake of his grandson), managed the publishing house at the time, and Johannes Hesse succeeded him in 1893.

Hesse grew up in a Swabian Pietist household, with the Pietist tendency to insulate believers into small, deeply thoughtful groups. Furthermore, Hesse described his father's Baltic German heritage as "an important and potent fact" of his developing identity. His father, Hesse stated, "always seemed like a very polite, very foreign, lonely, little-understood guest."[5] His father's tales from Estonia instilled a contrasting sense of religion in young Hermann. "[It was] an exceedingly cheerful, and, for all its Christianity, a merry world... We wished for nothing so longingly as to be allowed to see this Estonia... where life was so paradisiacal, so colourful and happy." Hermann Hesse's sense of estrangement from the Swabian petite bourgeoisie grew further through his relationship with his maternal grandmother Julie Gundert, née Dubois, whose French-Swiss heritage kept her from ever quite fitting in among that milieu.[5]

Childhood

From childhood, Hesse was headstrong and hard for his family to handle. In a letter to her husband, Hermann's mother Marie wrote: "The little fellow has a life in him, an unbelievable strength, a powerful will, and, for his four years of age, a truly astonishing mind. How can he express all that? It truly gnaws at my life, this internal fighting against his tyrannical temperament, his passionate turbulence [...] God must shape this proud spirit, then it will become something noble and magnificent – but I shudder to think what this young and passionate person might become should his upbringing be false or weak."[6]

Hesse showed signs of serious depression as early as his first year at school.[7] In his juvenilia collection Gerbersau, Hesse vividly describes experiences and anecdotes from his childhood and youth in Calw: the atmosphere and adventures by the river, the bridge, the chapel, the houses leaning closely together, hidden nooks and crannies, as well as the inhabitants with their admirable qualities, their oddities, and their idiosyncrasies. The fictional town of Gerbersau is pseudonymous for Calw, imitating the real name of the nearby town of Hirsau. It is derived from the German words gerber, meaning "tanner," and aue, meaning "meadow."[8] Calw had a centuries-old leather-working industry, and during Hesse's childhood the tanneries' influence on the town was still very much in evidence.[9] Hesse's favourite place in Calw was the St. Nicholas-Bridge (Nikolausbrücke), which is why a Hesse monument was built there in 2002.[10]

Hermann Hesse's grandfather Hermann Gundert, a doctor of philosophy and fluent in multiple languages, encouraged the boy to read widely, giving him access to his library, which was filled with the works of world literature. All this instilled a sense in Hermann Hesse that he was a citizen of the world. His family background became, he noted, "the basis of an isolation and a resistance to any sort of nationalism that so defined my life."[5]

Young Hesse shared a love of music with his mother. Both music and poetry were important in his family. His mother wrote poetry, and his father was known for his use of language in both his sermons and the writing of religious tracts. His first role model for becoming an artist was his half-brother, Theo, who rebelled against the family by entering a music conservatory in 1885.[11] Hesse showed a precocious ability to rhyme, and by 1889–90 had decided that he wanted to be a writer.[12]

Education

In 1881, when Hesse was four, the family moved to Basel, Switzerland, staying for six years and then returning to Calw. After successful attendance at the Latin School in Göppingen, Hesse entered the Evangelical Theological Seminary of Maulbronn Abbey in 1891. The pupils lived and studied at the abbey, one of Germany's most beautiful and well-preserved, attending 41 hours of classes a week. Although Hesse did well during the first months, writing in a letter that he particularly enjoyed writing essays and translating classic Greek poetry into German, his time in Maulbronn was the beginning of a serious personal crisis.[13] In March 1892, Hesse showed his rebellious character, and, in one instance, he fled from the Seminary and was found in a field a day later. Hesse began a journey through various institutions and schools and experienced intense conflicts with his parents. In May, after an attempt at suicide, he spent time at an institution in Bad Boll under the care of theologian and minister Christoph Friedrich Blumhardt. Later, he was placed in a mental institution in Stetten im Remstal, and then a boys' institution in Basel. At the end of 1892, he attended the Gymnasium in Cannstatt, now part of Stuttgart. In 1893, he passed the One Year Examination, which concluded his schooling. The same year, he began spending time with older companions and took up drinking and smoking.[14]

After this, Hesse began a bookshop apprenticeship in Esslingen am Neckar, but quit after three days. Then, in the early summer of 1894, he began a 14-month mechanic apprenticeship at a clock tower factory in Calw. The monotony of soldering and filing work made him turn himself toward more spiritual activities. In October 1895, he was ready to begin wholeheartedly a new apprenticeship with a bookseller in Tübingen. This experience from his youth, especially his time spent at the Seminary in Maulbronn, he returns to later in his novel Beneath the Wheel.

Becoming a writer

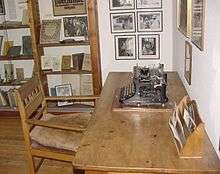

On 17 October 1895, Hesse began working in the bookshop in Tübingen, which had a specialized collection in theology, philology, and law.[15] Hesse's tasks consisted of organizing, packing, and archiving the books. After the end of each twelve-hour workday, Hesse pursued his own work, and he spent his long, idle Sundays with books rather than friends. Hesse studied theological writings and later Goethe, Lessing, Schiller, and Greek mythology. He also began reading Nietzsche in 1895,[16] and that philosopher's ideas of "dual… impulses of passion and order" in humankind was a heavy influence on most of his novels.[17]

By 1898, Hesse had a respectable income that enabled financial independence from his parents.[18] During this time, he concentrated on the works of the German Romantics, including much of the work from Clemens Brentano, Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff, Friedrich Hölderlin, and Novalis. In letters to his parents, he expressed a belief that "the morality of artists is replaced by aesthetics".

During this time, he was introduced to the home of Fräulein von Reutern, a friend of his family's. There he met with people his own age. His relationships with his contemporaries were "problematic", in that most of them were now at university. This usually left him feeling awkward in social situations.[19]

In 1896, his poem "Madonna" appeared in a Viennese periodical and Hesse released his first small volume of poetry, Romantic Songs. In 1897, a published poem of his, "Grand Valse", drew him a fan letter. It was from Helene Voigt, who the next year married Eugen Diederichs, a young publisher. To please his wife, Diederichs agreed to publish Hesse's collection of prose entitled One Hour After Midnight in 1898 (although it is dated 1899).[20] Both works were a business failure. In two years, only 54 of the 600 printed copies of Romantic Songs were sold, and One Hour After Midnight received only one printing and sold sluggishly. Furthermore, Hesse "suffered a great shock" when his mother disapproved of "Romantic Songs" on the grounds that they were too secular and even "vaguely sinful."[21]

From late 1899, Hesse worked in a distinguished antique book shop in Basel. Through family contacts, he stayed with the intellectual families of Basel. In this environment with rich stimuli for his pursuits, he further developed spiritually and artistically. At the same time, Basel offered the solitary Hesse many opportunities for withdrawal into a private life of artistic self-exploration, journeys and wanderings. In 1900, Hesse was exempted from compulsory military service due to an eye condition. This, along with nerve disorders and persistent headaches, affected him his entire life.

In 1901, Hesse undertook to fulfill a long-held dream and travelled for the first time to Italy. In the same year, Hesse changed jobs and began working at the antiquarium Wattenwyl in Basel. Hesse had more opportunities to release poems and small literary texts to journals. These publications now provided honorariums. His new bookstore agreed to publish his next work, Posthumous Writings and Poems of Hermann Lauscher.[22] In 1902, his mother died after a long and painful illness. He could not bring himself to attend her funeral, stating in a letter to his father: "I think it would be better for us both that I do not come, in spite of my love for my mother."[23]

Due to the good notices that Hesse received for Lauscher, the publisher Samuel Fischer became interested in Hesse[24] and, with the novel Peter Camenzind, which appeared first as a pre-publication in 1903 and then as a regular printing by Fischer in 1904, came a breakthrough: from now on, Hesse could make a living as a writer. The novel became popular throughout Germany.[25] Sigmund Freud "praised Peter Camenzind as one of his favourite readings."[26]

Between Lake Constance and India

Having realised he could make a living as a writer, Hesse finally married Maria Bernoulli (of the famous family of mathematicians[27]) in 1904, while her father, who disapproved of their relationship, was away for the weekend. The couple settled down in Gaienhofen on Lake Constance, and began a family, eventually having three sons. In Gaienhofen, he wrote his second novel, Beneath the Wheel, which was published in 1906. In the following time, he composed primarily short stories and poems. His story "The Wolf", written in 1906–07, was "quite possibly" a foreshadowing of Steppenwolf.[28]

His next novel, Gertrude, published in 1910, revealed a production crisis. He had to struggle through writing it, and he later would describe it as "a miscarriage". Gaienhofen was the place where Hesse's interest in Buddhism was re-sparked. Following a letter to Kapff in 1895 entitled Nirvana, Hesse had ceased alluding to Buddhist references in his work. In 1904, however, Arthur Schopenhauer and his philosophical ideas started receiving attention again, and Hesse discovered theosophy. Schopenhauer and theosophy renewed Hesse's interest in India. Although it was many years before the publication of Hesse's Siddhartha (1922), this masterpiece was to be derived from these new influences.

During this time, there also was increased dissonance between him and Maria, and in 1911 Hesse left for a long trip to Sri Lanka and Indonesia. He also visited Sumatra, Borneo, and Burma, but "the physical experience... was to depress him."[29] Any spiritual or religious inspiration that he was looking for eluded him,[30] but the journey made a strong impression on his literary work. Following Hesse's return, the family moved to Bern (1912), but the change of environment could not solve the marriage problems, as he himself confessed in his novel Rosshalde from 1914.

During the First World War

At the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Hesse registered himself as a volunteer with the Imperial army, saying that he could not sit inactively by a warm fireplace while other young authors were dying on the front. He was found unfit for combat duty, but was assigned to service involving the care of prisoners of war.[31] While most poets and authors of the warring countries quickly became embroiled in a tirade of mutual hate, Hesse, seemingly immune to the general war enthusiasm of the time,[32] wrote an essay titled "O Friends, Not These Tones" ("O Freunde, nicht diese Töne"),[a] which was published in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, on 3 November.[33] In this essay he appealed to his fellow intellectuals not to fall for nationalistic madness and hatred.[32][33] Calling for subdued voices and a recognition of Europe's common heritage,[34] Hesse wrote: [...] That love is greater than hate, understanding greater than ire, peace nobler than war, this exactly is what this unholy World War should burn into our memories, more so than ever felt before.[35] What followed from this, Hesse later indicated, was a great turning point in his life: For the first time, he found himself in the middle of a serious political conflict, attacked by the German press, the recipient of hate mail, and distanced from old friends. However, he did receive support from his friend Theodor Heuss, and the French writer Romain Rolland, who visited Hesse in August 1915.[36] In 1917, Hesse wrote to Rolland, "The attempt...to apply love to matters political has failed."[37]

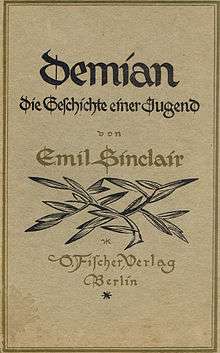

This public controversy was not yet resolved when a deeper life crisis befell Hesse with the death of his father on 8 March 1916, the serious illness of his son Martin, and his wife's schizophrenia. He was forced to leave his military service and begin receiving psychotherapy. This began for Hesse a long preoccupation with psychoanalysis, through which he came to know Carl Jung personally, and was challenged to new creative heights. Hesse and Jung both later maintained a correspondence with Chilean author, diplomat and Nazi sympathizer Miguel Serrano, who detailed his relationship with both figures in the book C.G. Jung & Hermann Hesse: A Record of Two Friendships. During a three-week period in September and October 1917, Hesse penned his novel Demian, which would be published following the armistice in 1919 under the pseudonym Emil Sinclair.

Casa Camuzzi

By the time Hesse returned to civilian life in 1919, his marriage had fallen apart. His wife had a severe episode of psychosis, but, even after her recovery, Hesse saw no possible future with her. Their home in Bern was divided, their children were accommodated in boarding houses and by relatives,[38] and Hesse resettled alone in the middle of April in Ticino. He occupied a small farm house near Minusio (close to Locarno), living from 25 April to 11 May in Sorengo. On 11 May, he moved to the town Montagnola and rented four small rooms in a castle-like building, the Casa Camuzzi. Here, he explored his writing projects further; he began to paint, an activity reflected in his next major story, "Klingsor's Last Summer", published in 1920. This new beginning in different surroundings brought him happiness, and Hesse later called his first year in Ticino "the fullest, most prolific, most industrious and most passionate time of my life."[39] In 1922, Hesse's novella Siddhartha appeared, which showed the love for Indian culture and Buddhist philosophy that had already developed earlier in his life. In 1924, Hesse married the singer Ruth Wenger, the daughter of the Swiss writer Lisa Wenger and aunt of Méret Oppenheim. This marriage never attained any stability, however.

In 1923, Hesse was granted Swiss citizenship. His next major works, Kurgast (1925) and The Nuremberg Trip (1927), were autobiographical narratives with ironic undertones and foreshadowed Hesse's following novel, Steppenwolf, which was published in 1927. In the year of his 50th birthday, the first biography of Hesse appeared, written by his friend Hugo Ball. Shortly after his new successful novel, he turned away from the solitude of Steppenwolf and married art historian Ninon Dolbin, née Ausländer. This change to companionship was reflected in the novel Narcissus and Goldmund, appearing in 1930. In 1931, Hesse left the Casa Camuzzi and moved with Ninon to a large house (Casa Hesse) near Montagnola, which was built according to his wishes.

In 1931, Hesse began planning what would become his last major work, The Glass Bead Game (a.k.a. Magister Ludi). In 1932, as a preliminary study, he released the novella Journey to the East. The Glass Bead Game was printed in 1943 in Switzerland. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1946.

Religious views

As reflected in Demian, and other works, he believed that "for different people, there are different ways to God";[40] but despite the influence he drew from Indian and Buddhist philosophies, he stated about his parents: “their Christianity, one not preached but lived, was the strongest of the powers that shaped and moulded me".[41][42]

Later life and death

Hesse observed the rise to power of Nazism in Germany with concern. In 1933, Bertolt Brecht and Thomas Mann made their travels into exile, each aided by Hesse. In this way, Hesse attempted to work against Hitler's suppression of art and literature that protested Nazi ideology. Hesse's third wife was Jewish, and he had publicly expressed his opposition to anti-Semitism long before then.[43] Hesse was criticized not for condemning the Nazi party, but his failure to criticize or support any political idea stemmed from his "politics of detachment [...] At no time did he openly condemn (the Nazis), although his detestation of their politics is beyond question."[44] Nazism, with its blood sacrifice of the individual to the state and the race, represented the opposite of everything he believed in. In March 1933, seven weeks after Hitler took power, Hesse wrote to a correspondent in Germany, "It is the duty of spiritual types to stand alongside the spirit and not to sing along when the people start belting out the patriotic songs their leaders have ordered them to sing." In the nineteen-thirties, Hesse made a quiet statement of resistance by reviewing and publicizing the work of banned Jewish authors, including Franz Kafka.[45] In the late 1930s, German journals stopped publishing Hesse's work, and the Nazis eventually banned it.

The Glass Bead Game was Hesse's last novel. During the last twenty years of his life, Hesse wrote many short stories (chiefly recollections of his childhood) and poems (frequently with nature as their theme). Hesse also wrote ironic essays about his alienation from writing (for instance, the mock autobiographies: Life Story Briefly Told and Aus den Briefwechseln eines Dichters) and spent much time pursuing his interest in watercolours. Hesse also occupied himself with the steady stream of letters he received as a result of the Nobel Prize and as a new generation of German readers explored his work. In one essay, Hesse reflected wryly on his lifelong failure to acquire a talent for idleness and speculated that his average daily correspondence exceeded 150 pages. He died on 9 August 1962, aged 85, and was buried in the cemetery at San Abbondio in Montagnola, where Hugo Ball and the conductor Bruno Walter are also buried.[46]

Influence

In his time, Hesse was a popular and influential author in the German-speaking world; worldwide fame only came later. Hesse's first great novel, Peter Camenzind, was received enthusiastically by young Germans desiring a different and more "natural" way of life in this time of great economic and technological progress in the country (see also Wandervogel movement).[47] Demian had a strong and enduring influence on the generation returning home from the First World War.[48] Similarly, The Glass Bead Game, with its disciplined intellectual world of Castalia and the powers of meditation and humanity, captivated Germans' longing for a new order amid the chaos of a broken nation following the loss in the Second World War.[49]

Towards the end of his life, German (born Bavarian) composer Richard Strauss (1864–1949) set three of Hesse's poems to music in his song cycle Four Last Songs for soprano and orchestra (composed 1948, first performed posthumously in 1950): "Frühling" ("Spring"), "September", and "Beim Schlafengehen" ("On Going to Sleep").

In the 1950s, Hesse's popularity began to wane, while literature critics and intellectuals turned their attention to other subjects. In 1955, the sales of Hesse's books by his publisher Suhrkamp reached an all-time low. However, after Hesse's death in 1962, posthumously published writings, including letters and previously unknown pieces of prose, contributed to a new level of understanding and appreciation of his works.[50]

By the time of Hesse's death in 1962, his works were still relatively little read in the United States, despite his status as a Nobel laureate. A memorial published in The New York Times went so far as to claim that Hesse's works were largely "inaccessible" to American readers. The situation changed in the mid-1960s, when Hesse's works suddenly became bestsellers in the United States.[51] The revival in popularity of Hesse's works has been credited to their association with some of the popular themes of the 1960s counterculture (or hippie) movement. In particular, the quest-for-enlightenment theme of Siddhartha, Journey to the East, and Narcissus and Goldmund resonated with those espousing counter-cultural ideals. The "magic theatre" sequences in Steppenwolf were interpreted by some as drug-induced psychedelia although there is no evidence that Hesse ever took psychedelic drugs or recommended their use.[52] To a large part, the Hesse boom in the United States can be traced back to enthusiastic writings by two influential counter-culture figures: Colin Wilson and Timothy Leary.[53] From the United States, the Hesse renaissance spread to other parts of the world and even back to Germany: more than 800,000 copies were sold in the German-speaking world from 1972 to 1973. In a space of just a few years, Hesse became the most widely read and translated European author of the 20th century.[51] Hesse was especially popular among young readers, a tendency which continues today.[54]

There is a quote from Demian on the cover of Santana's 1970 album Abraxas, revealing the source of the album's title.

Hesse's Siddhartha is one of the most popular Western novels set in India. An authorised translation of Siddhartha was published in the Malayalam language in 1990, the language that surrounded Hesse's grandfather, Hermann Gundert, for most of his life. A Hermann Hesse Society of India has also been formed. It aims to bring out authentic translations of Siddhartha in all Indian languages and has already prepared the Sanskrit,[55] Malayalam[56] and Hindi[57] translations of Siddhartha. One enduring monument to Hesse's lasting popularity in the United States is the Magic Theatre in San Francisco. Referring to "The Magic Theatre for Madmen Only" in Steppenwolf (a kind of spiritual and somewhat nightmarish cabaret attended by some of the characters, including Harry Haller), the Magic Theatre was founded in 1967 to perform works by new playwrights. Founded by John Lion, the Magic Theatre has fulfilled that mission for many years, including the world premieres of many plays by Sam Shepard.

There is also a theater in Chicago named after the novel, Steppenwolf Theater.

Throughout Germany, many schools are named after him. The Hermann-Hesse-Literaturpreis is a literary prize associated with the city of Karlsruhe that has been awarded since 1957.[58] Since 1990,[59] the Calw Hermann Hesse Prize has been awarded every two years alternately to a German-language literary journal and a translator of Hesse's work.[60] The Internationale Hermann-Hesse-Gesellschaft (unofficial English name: International Hermann Hesse Society) was founded in 2002 on the 125th birthday of Hesse and began awarding its Hermann Hesse prize in 2017.[61]

Musician Steve Adey adapted the poem How Heavy the Days on his 2017 LP "Do Me a Kindness".

The band Steppenwolf took its name from Hesse's novel.

Awards

- 1906 – Bauernfeld-Preis

- 1928 – Mejstrik-Preis of the Schiller Foundation in Vienna

- 1936 – Gottfried-Keller-Preis

- 1946 – Goethe Prize

- 1946 – Nobel Prize in Literature

- 1947 – Honorary Doctorate from the University of Bern

- 1950 – Wilhelm Raabe Literature Prize

- 1954 – Pour le Mérite

- 1955 – Peace Prize of the German Book Trade

Bibliography

- (1899) Eine Stunde hinter Mitternacht—novella

- (1900) Hermann Lauscher—collection of poetry and prose

- (1904) Peter Camenzind—novel

- (1906) Unterm Rad (Beneath the Wheel; also published as The Prodigy)—novel

- (1908) Freunde—novella

- (1910) Gertrud—novel

- (1913) Besuch aus Indien (Visitor from India)—nonfiction/philosophy

- (1914) In the Old Sun—novella

- (1914) Roßhalde—novel

- (1915) Knulp (also published as Three Tales from the Life of Knulp)—novel

- (1916) Schön ist die Jugend—novella

- (1919) Strange News from Another Star (originally published as Märchen)—collection of short stories written between 1913 and 1918

- (1919) Demian (published under the pen name Emil Sinclair)—novel

- (1919) Klein und Wagner—novella

- (1920) Blick ins Chaos (A Glimpse into Chaos)—essays

- (1920) Klingsors letzter Sommer (Klingsor's Last Summer)—novella

- (1920) Wandering—notes and sketches

- (1922) Siddhartha—novel

- (1927) Der Steppenwolf—novel

- (1930) Narziß und Goldmund (Narcissus and Goldmund; also published as Death and the Lover)—novel

- (1932) Die Morgenlandfahrt (Journey to the East)—novel

- (1943) Das Glasperlenspiel (The Glass Bead Game; also published as Magister Ludi)—novel

- (1970) Poems (21 poems written between 1899 and 1921)—poetry

- (1971) If the War Goes On—essays

- (1972) Stories of Five Decades (23 stories written between 1899 and 1948)—collection of stories

- (1972) Autobiographical Writings (including "A Guest at the Spa")—collection of prose pieces

- (1975) Crisis: Pages from a Diary—poetry

- (1979) Hours in the Garden and Other Poems (written during the same period as The Glass Bead Game)—poetry

Film adaptations

- 1966: El lobo estepario (based on Steppenwolf)

- 1971: Zachariah (based on Siddartha)

- 1972: Siddhartha

- 1974: Steppenwolf

- 1981: Kinderseele

- 1989: Francesco

- 1996: Ansatsu (based on Demian)

- 2003: Poem: I Set My Foot Upon the Air and It Carried Me

- 2003: Siddhartha

- 2012: Die Heimkehr

References

- German Wikipedia, other sources.

- Gundert, Hermann (1872). A Malayalam and English Dictionary. C. Stolz. p. 14.

- Gundert, Adele, Marie Hesse: Ein Lebensbild in Briefen und Tagebuchern [Marie Hesse: A life picture in letters and diaries] (in German) as quoted in Freedman (1978) pp. 18–19.

- Weltbürger – Hermann Hesses übernationales und multikulturelles Denken und Wirken [Hermann Hesse's international and multicultural thinking and work] (exhibition) (in German), City of Calw: Hermann-Hesse-Museum, 2 July 2010 – 7 February 2010.

- Hesse, Hermann (1964), Briefe [Letters] (in German), Frankfurt am Main: Verlag Suhrkamp, p. 414.

- Volker Michels (ed.): Über Hermann Hesse. Verlag Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main, vol 1: 1904–1962, Repräsentative Textsammlung zu Lebzeiten Hesses. 2nd ed., 1979, ISBN 3-518-06831-8, p. 400.

- Freedman, p. 30

- An English equivalent would be "Tannersmead."

- Siegfried Greiner Hermann Hesse, Jugend in Calw, Thorbecke (1981), ISBN 3799520090 p. viii

- Smith, Rocky (5 April 2010). "A Special Fondness". Mr. Writer. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- Freedman (1978) pp. 30–32

- Freedman (1978) p. 39

- Zeller, pp. 26–30

- Freedman (1978) p. 53

- J. J. Heckenhauer.

- Freedman (1978) p. 69.

- Freedman (1978) p. 111.

- Franklin, Wilbur (1977). The concept of 'the human' in the work of Hermann Hesse and Paul Tillich (PDF) (Thesis). St Andrews University.

- Freedman (1978) p. 64.

- Freedman(1978) pp. 78–80.

- Freedman(1978), p. 79.

- Freedman(1978) p. 97.

- Freedman (1978), pp. 99–101.

- Freedman (1978) p. 107.

- Freedman (1978) p. 108.

- Freedman (1978) p. 117.

- Gustav Emil Müller, Philosophy of Literature, Ayer Publishing, 1976.

- Freedman (1978) p. 140

- Freedman (1978) p. 149

- Kirsch, Adam (19 November 2018). "Hermann Hesse's arrested development". The New Yorker. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- "Hermann Hesse Schriftsteller" (in German). Deutsches Historisches Museum. Retrieved 15 January 2008.

- Zeller, p. 83

- Mileck, Joseph (1977). Hermann Hesse: Biography and Bibliography. Vol.1. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-520-02756-5. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- Freedman (1978) p. 166

- Zeller, pp. 83–84

- Freedman (1978) pp. 170–71.

- Freedman (1978) p. 189

- Zeller, p. 93

- Zeller, p. 94

- "The Religious Affiliation of Nobel Prize-winning author Hermann Hesse", Adherents.

- Hesse, Hermann (1951), Gesammelte Werke [Collected Works] (in German), Suhrkamp Verlag, p. 378,

Von ihnen bin ich erzogen, von ihnen habe ich die Bibel und Lehre vererbt bekommen, Ihr nicht gepredigtes, sondern gelebtes Christentum ist unter den Mächten, die mich erzogen und geformt haben, die stärkste gewesen [I have been educated by them; I have inherited the Bible and doctrine from them; their Christianity, not preached, but lived, has been the strongest among the powers that educated and formed me]

. Another translation: "Not the preached, but their practiced Christianity, among the powers that shaped and molded me, has been the strongest". - Hilbert, Mathias (2005), Hermann Hesse und sein Elternhaus – Zwischen Rebellion und Liebe: Eine biographische Spurensuche [Hermann Hesse and his Parents’ House – Between Rebellion and Love: A biographical search] (in German), Calwer Verlag, p. 226.

- Galbreath (1974) Robert. "Hermann Hesse and the Politics of Detachment", p. 63, Political Theory, vol. 2, No 1 (Feb 1974).

- Galbreath (1974) Robert. "Hermann Hesse and the Politics of Detachment", p. 64, Political Theory, vol. 2, No 1 (Feb 1974)

- https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/11/19/hermann-hesses-arrested-development

- Mileck, Joseph (29 January 1981). Hermann Hesse: Life and Art. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 360. ISBN 9780520041523.

- Prinz, pp. 139–42

- Zeller, p. 90

- Zeller, p. 186

- Zeller, pp. 180–81

- Zeller, p. 185

- Zeller p. 189

- Zeller, p. 188

- Zeller p. 186

- Hesse, Hermann. Siddhartha. Sanskrit Translation by L. Sulochana Devi. Trivandrum,Hermann Hesse Society of India, 2008

- Hesse, Hermann. Siddhartha. Malaylam Translation by R. Raman Nair. Trivandrum, CSIS, 1993

- Hesse, Hermann. Siddhartha. Hindi Translation by Prabakaran, hebbar Illath. Trivandrum,Hermann Hesse Society of India, 2012

- Hermann-Hesse-Preis 2003 Archived 9 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine. karlsruhe.de

- The winners of the Calw Hermann Hesse Prize

- Calw Hermann Hesse Prize. Hermann-hesse.de (18 September 2012). Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- Adolf Muschg erster Preisträger des neu ausgelobten Preis der Internationalen Hermann Hesse Gesellschaft (in German)

Sources

- Freedman, Ralph, Hermann Hesse: Pilgrim of Crisis: A Biography, Pantheon Books, NY, 1978.

- Montalbán, Manuel Vázquez, Scenes from World Literature and Portraits of Greatest Authors, illustrated by Willi Glasauer, Círculo de Lectores, Barcelona, Spain, 1988.

- Zeller, Bernhard, Hermann Hesse, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg, 2005. ISBN 3499506769.

- Prinz, Alois, Und jedem Anfang wohnt ein Zauber inne: Die Lebensgeschichte des Hermann Hesse, Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, 2006. ISBN 9783518457429.

External links

- Publications by and about Hermann Hesse in the catalogue Helveticat of the Swiss National Library

- "Literary estate of Hermann Hesse". HelveticArchives. Swiss National Library.

- Complete bibliography at Nobelprize.org

- Works by Hermann Hesse at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Hermann Hesse at Internet Archive

- Works by Hermann Hesse at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Hermann Hesse at Open Library

- Hermann Hesse Page – in German and English, maintained by Professor Gunther Gottschalk

- Hermann Hesse Portal

- Hesse-Film.de, German Documentary about his life – in German

- Community of the Journeyer to the East – in German and English

- The painter Hermann Hesse Galerie Ludorff, Düsseldorf, Germany

- "Hermann, Hesse". SIKART Lexicon on art in Switzerland.

- Lajos Kovács. "Erziehung in Hermann Hesses "Glasperlenspiel" – Diplomarbeit". GRIN.