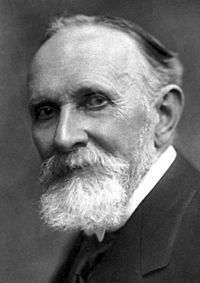

Carl Spitteler

Carl Friedrich Georg Spitteler (24 April 1845 – 29 December 1924) was a Swiss poet who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1919 "in special appreciation of his epic, Olympian Spring". His work includes both pessimistic and heroic poems.

Carl Friedrich Georg Spitteler | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 24 April 1845 Liestal, Switzerland |

| Died | 29 December 1924 (aged 79) Lucerne, Switzerland |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Language | German |

| Nationality | Swiss |

| Education | University of Basel, Heidelberg University |

| Notable awards | Nobel Prize in Literature 1919 |

Biography

Spitteler was born in Liestal. His father was an official of the government, being Federal Secretary of the Treasury from 1849–56. Young Spitteler attended the gymnasium at Basel, having among his teachers philologist Wilhelm Wackernagel and historian Jakob Burckhardt. From 1863 he studied law at the University of Zurich. In 1865–1870 he studied theology in the same institution, at Heidelberg and Basel, though when a position as pastor was offered him, he felt that he must decline it. He had begun to realize his mission as an epic poet and therefore refused to work in the field for which he had prepared himself.[1]

Later he worked in Russia as tutor, starting from August 1871, remaining there (with some periods in Finland) until 1879. Later he was elementary teacher in Bern and La Neuveville, as well as journalist for the Der Kunstwart and as editor for the Neue Zürcher Zeitung. In 1883 Spitteler married Marie op der Hoff, previously his pupil in Neuveville.

In 1881 Spitteler published the allegoric prose poem Prometheus and Epimetheus, published under the pseudonym Carl Felix Tandem, and showing contrasts between ideals and dogmas through the two mythological figures of the titles. This 1881 edition was given an extended psychological exegesis by Carl Gustav Jung in his book Psychological Types (published in 1921). Late in life, Spitteler reworked Prometheus and Epimetheus and published it under his true name, with the new title Prometheus der Dulder (Prometheus the Sufferer, 1924).

In 1882 he published his Extramundana, a collection of poems. He gave up teaching in 1885 and devoted himself to a journalistic career in Basel. Now his works began to come in rapid succession. In 1891 there appeared Friedli, der Kalderi, a collection of short stories, in which Spitteler, as he himself says, depicted Russian realism. Literarische Gleichnisse appeared in 1892, and Balladen in 1896.[1]

In 1900–1905 Spitteler wrote the powerful allegoric-epic poem, in iambic hexameters, Olympischer Frühling (Olympic Spring). This work, mixing fantastic, naturalistic, religions and mythological themes, deals with human concern towards the universe. His prose works include Die Mädchenfeinde (Two Little Misogynists, 1907), about his autobiographical childhood experiences, the dramatic Conrad der Leutnant (1898), in which he show influence from the previously opposed Naturalism, and the autobiographical novella Imago (1906), examining the role of the unconscious in the conflict between a creative mind and the middle-class restrictions with internal monologue.

During World War I he opposed the pro-German attitude of the Swiss German-speaking majority, a position put forward in the essay "Unser Schweizer Standpunkt". In 1919 he won the Nobel Prize. Spitteler died at Lucerne in 1924.

Carl Spitteler's estate is archived in the Swiss Literary Archives in Bern, in the Zürich Central Library and in the Dichter- und Stadtmuseum in Liestal.

Pop Culture

Carl Jung claimed his idea of the archetype of the Anima was based upon what Spitteler described as 'My Lady Soul'. Musician David Bowie, who famously described himself as Jungian, wrote a song in 1973 entitled "Lady Grinning Soul".[2]

Works

- Prometheus und Epimetheus (1881)

- Extramundana (1883, seven cosmic myths)

- Schmetterlinge ("Butterflies", 1889)

- Der Parlamentär (1889)

- Literarische Gleichnisse ("Literary Parables”, 1892)

- Gustav (1892)

- Balladen (1896)

- Conrad der Leutnant (1898)

- Lachende Wahrheiten (1898, essays)

- Der olympische Frühling (1900–1905, revised 1910)

- Glockenlieder ("Grass and Bell Songs", 1906)

- Imago (1906, novel)

- Die Mädchenfeinde (Two Little Misogynists, 1907)

- Meine frühesten Erlebnisse ("My Earliest Experiences", 1914, biographical)

- Prometheus der Dulder ("Prometheus the Suffering”, 1924)

References

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: William F. Hauhart (1920). . In Rines, George Edwin (ed.). Encyclopedia Americana.

- Stark, T., “Crashing Out with Sylvian: David Bowie, Carl Jung and the Unconscious” in Deveroux, E., M.Power and A. Dillane (eds) David Bowie: Critical Perspectives: Routledge Press Contemporary Music Series. 2015 (chapter 5) https://tanjastark.com/2015/06/22/crashing-out-with-sylvian-david-bowie-carl-jung-and-the-unconscious/

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carl Spitteler. |

- Literary estate of Carl Spitteler in the archive database HelveticArchives of the Swiss National Library

- Publications by and about Carl Spitteler in the catalogue Helveticat of the Swiss National Library

- Carl Spitteler on Nobelprize.org

- Official Site of the Carl Spitteler Foundation

- Works by or about Carl Spitteler at Internet Archive

- Works by Carl Spitteler at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Newspaper clippings about Carl Spitteler in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW