Languages of the Netherlands

The official language of the Netherlands is Dutch, spoken by almost all people in the Netherlands. Dutch is also spoken and official in Aruba, Bonaire, Belgium, Curaçao, Saba, Sint Eustatius, Sint Maarten and Suriname. It is a West Germanic, Low Franconian language that originated in the Early Middle Ages (c. 470) and was standardised in the 16th century.

| Languages of Netherlands | |

|---|---|

| Official | Dutch (>98%) |

| Regional | West Frisian (2.50%),[1] English (BES Islands),[2] Papiamento (Bonaire);[2][3] Dutch Low Saxon (10.9%)[4] Limburgish (4.50%) |

| Immigrant | Indonesian (2%), Varieties of Arabic (1.5%), Turkish (1.5%), Berber languages (1%), Polish (1%) See further: Immigration to the Netherlands |

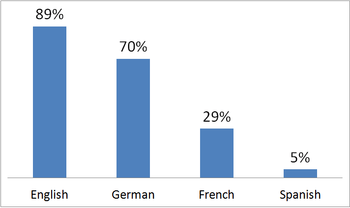

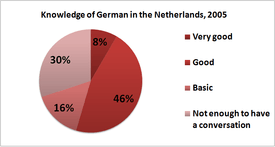

| Foreign | English (89%) (excluding the BES Islands) German (71%), French (29%), Spanish (5%)[5] |

| Signed | Dutch Sign Language |

| Keyboard layout | US international QWERTY  |

| Life in the Netherlands |

|---|

|

|

Society

|

|

Government |

| This article is a part of a series on |

| Dutch |

|---|

| Dutch Low Saxon dialects |

| West Low Franconian dialects |

| East Low Franconian dialects |

|

There are also some recognised provincial languages and regional dialects.

- West Frisian is a co-official language in the province of Friesland. West Frisian is spoken by 453,000 speakers.[7]

- English is an official language in the special municipalities of Saba and Sint Eustatius (BES Islands), as well as the autonomous states of Curaçao and Sint Maarten. It is widely spoken on Saba and Sint Eustatius (see also: English language in the Netherlands). On Saba and St. Eustatius, the majority of the education is in English only, with some bilingual English-Dutch schools.

- Papiamento is an official language in the special municipality of Bonaire. It is also the native language in the autonomous states of Curaçao and Aruba.

- Several dialects of Dutch Low Saxon (Nederlands Nedersaksisch in Dutch) are spoken in much of the north-east of the country and are recognised as regional languages according to the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. Low Saxon is spoken by 1,798,000 speakers.[4]

- Another Low Franconian dialect is Limburgish, which is spoken in the south-eastern province of Limburg. Limburgish is spoken by 825,000 speakers. Though there are movements to have Limburgish recognised as an official language (meeting with varying amounts of success,) it is important to note that Limburgish in fact consists of many differing dialects that share some common aspects, but are quite different.[8]

However, both Low Saxon and Limburgish spread across the Dutch-German border and belong to a common Dutch-German dialect continuum.

The Netherlands also has its separate Dutch Sign Language, called Nederlandse Gebarentaal (NGT). It is still waiting for recognition and has 17,500 users.[9]

There is a trend of learning foreign languages in the Netherlands: between 90%[6] and 93%[10] of the total population are able to converse in English, 71% in German, 29% in French and 5% in Spanish.

Minority languages, regional languages and dialects in the Benelux

West Frisian dialects

West Frisian is an official language in the Dutch province of Friesland (Fryslân in West Frisian). The government of the Frisian province is bilingual. Since 1996 West Frisian has been recognised as an official minority language in the Netherlands under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, although it had been recognised by the Dutch government as the second state language (tweede rijkstaal), with official status in Friesland, since the 1950s.

- Westlauwers Frisian

- Wood Frisian

- Clay Frisian

- Noordhoeks

- Zuidwesthoeks

- Hindeloopers

- Westers

- Aasters

- Schiermonnikoogs

Low Saxon dialects

- Gronings-East Frisian

- Kollumerpompsters

- Hoogelandsters

- Oldambtsters

- Westerwolds

- Veenkoloniaals

- Stadsgronings

- Noordenvelds (Noord-Drents)

- Westerkwartiers

- Midden-Drents

- Zuid-Drents

- Stellingwerfs

- Guelderish-Overijssels

- Twents

- Oost-Twents

- Vriezenveens (this is actually a separate dialect because of West Frisian influences)

- Twents-Graafschaps

- Veluws

- Oost-Veluws

- West-Veluws

Low Franconian dialects

- West Frisian

- Mainland West Frisian

- Insular West Frisian

- Stadsfries

- Midlands

- Amelands

- Bildts

- Hollandic

- Kennemerlandic

- Zaans

- Waterlandic

- Amsterdams

- Strand-Hollands

- Haags

- Rotterdams

- Utrechts-Alblasserwaards

- Westhoeks

- Zeelandic-West Flemish (including French Flemish)

- Zeelandic

- Burger-Zeeuws

- Coastal West Flemish

- Continental West Flemish

- East Flemish

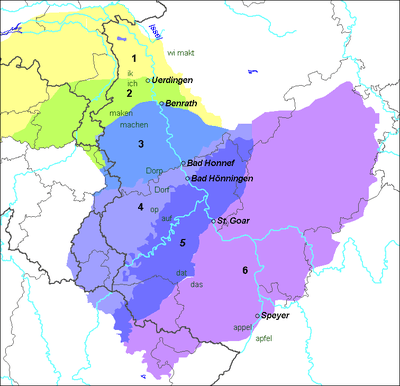

—— Low Franconian (Dutch) —— —— West Central German (Central and Rhine Franconian) ——

- South Guelderish (Kleverlands)

- Rivierenlands

- Liemers

- Nijmeegs

- North Limburgian

- Brabantian

- Northwest Brabantian

- Central north Brabantian

- East Brabantian

- Kempen Brabantian

- South Brabantian

- Limburgish

- West Limburgish

- Central Limburgish

- Southeast Limburgish

- Low Dietsch

Central Franconian dialects

Note that Ripuarian is not recognised as a regional language of the Netherlands.

Dialects fully outside the Netherlands

Luxembourgish is divided into Moselle Luxembourgish, West Luxembourgish, East Luxembourgish, North Luxembourgish and City Luxembourgish. The Oïl dialects in the Benelux are Walloon (divided into West Walloon, Central Walloon, East Walloon and South Walloon), Lorrain (including Gaumais), Champenois and Picard (including Tournaisis).

References

Footnotes

- "Regeling - Instellingsbesluit Consultatief Orgaan Fries 2010 - BWBR0027230". wetten.overheid.nl. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- "wetten.nl - Regeling - Invoeringswet openbare lichamen Bonaire, Sint Eustatius en Saba - BWBR0028063". Wetten.overheid.nl. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- "Regeling - Wet openbare lichamen Bonaire, Sint Eustatius en Saba - BWBR0028142". Wetten.overheid.nl. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- "Taal in Nederland .:. Nedersaksisch". taal.phileon.nl. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- "EUROPEANS AND THEIR LANGUAGES" (PDF). Web.archive.org. 6 January 2016. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "EUROPEANS AND THEIR LANGUAGES" (PDF). Ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2017-08-23.

- "Taal in Nederland .:. Fries". taal.phileon.nl. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- "Taal in Nederland .:. Limburgs". taal.phileon.nl. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- Rapport "Meer dan een gebaar" en "actualisatie 1997-2001

- ""English in the Netherlands: Functions, forms and attitudes" p. 316 and onwards" (PDF). Alisonedwardsdotcom.files.wordpress.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- "Gemeente Kerkrade - Kirchröadsj Plat". www.kerkrade.nl. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- "Cittaslow Vaals: verrassend, veelzijdig, veelkleurig". Retrieved 9 September 2015. The PDF file can be accessed at the bottom of the page. The relevant citation is on the page 13: "De enige taal waarin Vaals echt te beschrijven en te bezingen valt is natuurlijk het Völser dialect. Dit dialect valt onder het zogenaamde Ripuarisch."

Notations

- "Taal in Nederland .:. Fries". taal.phileon.nl. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- "Taal in Nederland .:. Nedersaksisch". taal.phileon.nl. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- "Taal in Nederland .:. Limburgs". taal.phileon.nl. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- Ginsburgh, Victor; Ignacio Ortuño-Ortin; Shlomo Weber (February 2005). "Why Do People Learn Foreign Languages?" (PDF). Université libre de Bruxelles. Archived from the original (pdf) on 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2007-10-10. - specifically, see Table 2.