West Germanic languages

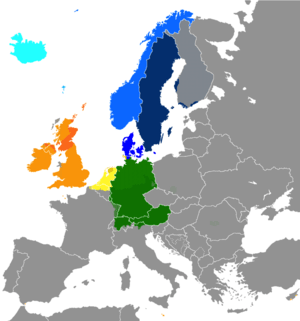

The West Germanic languages constitute the largest of the three branches of the Germanic family of languages (the others being the North Germanic and the extinct East Germanic languages).

| West Germanic | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Originally between the Rhine, Alps, Elbe, and North Sea; today worldwide |

| Linguistic classification | Indo-European

|

| Subdivisions |

|

| ISO 639-5 | gmw |

| Linguasphere | 52-AB & 52-AC |

| Glottolog | west2793[1] |

| |

The three most prevalent West Germanic languages are English, German, and Dutch. The family also includes other High and Low German languages including Afrikaans and Yiddish (which are daughter languages of Dutch and German, respectively), in addition to other Franconian languages, like Luxembourgish, and Ingvaeonic (North Sea Germanic) languages next to English, such as the Frisian languages and Scots. Additionally, several creoles, patois, and pidgins are based on Dutch, English and German as they were languages of colonial empires.

History

Origins

The West Germanic languages share many lexemes not existing in North Germanic or East Germanic—archaisms as well as common neologisms.

Existence of a West Germanic proto-language

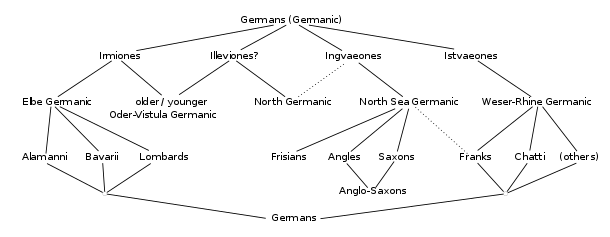

Most scholars doubt that there was a Proto-West-Germanic proto-language common to the West Germanic languages and no others, though a few maintain that Proto-West-Germanic existed.[2] Most agree that after East Germanic broke off (an event usually dated to the 2nd or 1st century BC), the remaining Germanic languages, the Northwest Germanic languages, divided into four main dialects:[3] North Germanic, and the three groups conventionally called "West Germanic", namely

- North Sea Germanic, ancestral to Anglo-Frisian and Old Saxon

- Weser-Rhine Germanic, ancestral to Low Franconian and in part to some of the Central Franconian and Rhine Franconian dialects of Old High German

- Elbe Germanic, ancestral to the Upper German and most Central German dialects of Old High German, and the extinct Langobardic language.

Although there is quite a bit of knowledge about North Sea Germanic or Anglo-Frisian (due to characteristic features of its daughter languages, Anglo-Saxon/Old English and Old Frisian), linguists know almost nothing about "Weser-Rhine Germanic" and "Elbe Germanic". In fact, these two terms were coined in the 1940s to refer to groups of archaeological findings rather than linguistic features. Only later were these terms applied to hypothetical dialectal differences within both regions. Even today, the very small number of Migration Period runic inscriptions from this area—many of them illegible, unclear or consisting only of one word, often a name—is insufficient to identify linguistic features specific to the two supposed dialect groups.

Evidence that East Germanic split off before the split between North and West Germanic comes from a number of linguistic innovations common to North and West Germanic,[4] including:

- The lowering of Proto-Germanic ē (/ɛː/, also written ǣ) to ā.[5]

- The development of umlaut.

- The rhotacism of /z/ to /r/.

- The development of the demonstrative pronoun ancestral to English this.

Under this view, the properties that the West Germanic languages have in common separate from the North Germanic languages are not necessarily inherited from a "Proto-West-Germanic" language, but may have spread by language contact among the Germanic languages spoken in central Europe, not reaching those spoken in Scandinavia or reaching them much later. Rhotacism, for example, was largely complete in West Germanic at a time when North Germanic runic inscriptions still clearly distinguished the two phonemes. There is also evidence that the lowering of ē to ā occurred first in West Germanic and spread to North Germanic later, since word-final ē was lowered before it was shortened in West Germanic, whereas in North Germanic the shortening occurred first, resulting in e that later merged with i. However, there are also a number of common archaisms in West Germanic shared by neither Old Norse nor Gothic. Some authors who support the concept of a West Germanic proto-language claim that not only shared innovations can require the existence of a linguistic clade but that there can be also archaisms that cannot be explained simply as retentions later lost in the North or East because this assumption can produce contradictions with attested features of these other branches.

The debate on the existence of a Proto-West-Germanic clade was recently summarized:

That North Germanic is .. a unitary subgroup [of Proto-Germanic] is completely obvious, as all of its dialects shared a long series of innovations, some of them very striking. That the same is true of West Germanic has been denied, but I will argue in vol. ii that all the West Germanic languages share several highly unusual innovations that virtually force us to posit a West Germanic clade. On the other hand, the internal subgrouping of both North Germanic and West Germanic is very messy, and it seems clear that each of those subfamilies diversified into a network of dialects that remained in contact for a considerable period of time (in some cases right up to the present).[6]

The reconstruction of Proto-West-Germanic

Several scholars have published reconstructions of Proto-West-Germanic morphological paradigms[7] and many authors have reconstructed individual Proto-West-Germanic morphological forms or lexemes. The first comprehensive reconstruction of the Proto-West-Germanic language was published in 2013 by Wolfram Euler.[8]

Dating Early West Germanic

If indeed Proto-West-Germanic existed, it must have been between the 2nd and 4th centuries. Until the late 2nd century AD, the language of runic inscriptions found in Scandinavia and in Northern Germany were so similar that Proto-North-Germanic and the Western dialects in the south were still part of one language ("Proto-Northwest-Germanic"). After that, the split into West and North Germanic occurred. By the 4th and 5th centuries the great migration set in which probably helped diversify the West Germanic family even more.

It has been argued that, judging by their nearly identical syntax, the West Germanic dialects were closely enough related to have been mutually intelligible up to the 7th century.[9] Over the course of this period, the dialects diverged successively. The High German consonant shift that occurred mostly during the 7th century AD in what is now southern Germany, Austria, and Switzerland can be considered the end of the linguistic unity among the West Germanic dialects, although its effects on their own should not be overestimated. Bordering dialects very probably continued to be mutually intelligible even beyond the boundaries of the consonant shift. In fact, many dialects of Limburgish and Ripuarian are still mutually intelligible today.

Middle Ages

During the Early Middle Ages, the West Germanic languages were separated by the insular development of Old and Middle English on one hand, and by the High German consonant shift on the continent on the other.

The High German consonant shift distinguished the High German languages from the other West Germanic languages. By early modern times, the span had extended into considerable differences, ranging from Highest Alemannic in the South (the Walliser dialect being the southernmost surviving German dialect) to Northern Low Saxon in the North. Although both extremes are considered German, they are not mutually intelligible. The southernmost varieties have completed the second sound shift, whereas the northern dialects remained unaffected by the consonant shift.

Of modern German varieties, Low German is the one that most resembles modern English. The district of Angeln (or Anglia), from which the name English derives, is in the extreme northern part of Germany between the Danish border and the Baltic coast. The area of the Saxons (parts of today's Schleswig-Holstein and Lower Saxony) lay south of Anglia. The Angles and Saxons, two Germanic tribes, in combination with a number of other peoples from northern Germany and the Jutland Peninsula, particularly the Jutes, settled in Britain following the end of Roman rule in the island. Once in Britain, these Germanic peoples eventually developed a shared cultural and linguistic identity as Anglo-Saxons; the extent of the linguistic influence of the native Romano-British population on the incomers is debatable.

Family tree

Note that divisions between subfamilies of continental Germanic languages are rarely precisely defined; most form dialect continua, with adjacent dialects being mutually intelligible and more separated ones not.

- North Sea Germanic / Ingvaeonic languages

- Anglo-Frisian languages

- English Languages/Anglic

- Frisian languages

- Low German / Low Saxon

- Northern Low Saxon

- Schleswig dialects

- Holstein dialects

- Westphalian

- Eastphalia dialects

- Brandenburg dialects ("Märkisch")

- Pommeranian (moribund)

- Low Prussian (moribund)

- Dutch Low Saxon

- Anglo-Frisian languages

- Weser-Rhine Germanic / Istvaeonic languages

- Dutch

- West Flemish

- East Flemish

- Zeelandic

- Hollandic

- Brabantine

- East Dutch (Zuid-Gelders/Clevian/Meuse-Rhenish)

- Afrikaans

- Limburgian

- Dutch

- Elbe Germanic / Irminonic languages / High German

- German

- Alemannic, including Swiss German and Alsatian

- Swabian

- Austro-Bavarian

- East Franconian

- South Franconian

- Rhine Franconian, including the dialects of Hessen, Pennsylvania German, and most of those from Lorraine

- Ripuarian

- Thuringian

- Upper Saxon German

- Silesian (moribund)

- Lombardic aka Langobardic (extinct, unless Cimbrian and Mocheno are in fact Langobardic remnants.)

- High Prussian (moribund)

- Luxembourgish

- Pennsylvania German language

- Yiddish (a language based on Eastern-Central dialects of late Middle High German/Early New High German)

- German

Comparison of phonological and morphological features

The following table shows a list of various linguistic features and their extent among the West Germanic languages. Some may only appear in the older languages but are no longer apparent in the modern languages.

| Old English | Old Frisian | Old Saxon | Old Dutch | Old Central German |

Old Upper German | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palatalisation of velars | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Unrounding of front rounded vowels | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Loss of intervocalic *-h- | Yes | Yes | Developing | Yes | Developing | No |

| Class II weak verb ending *-(ō)ja- | Yes | Yes | Sometimes | No | No | No |

| Merging of plural forms of verbs | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Ingvaeonic nasal spirant law | Yes | Yes | Yes | Rare | No | No |

| Loss of the reflexive pronoun | Yes | Yes | Most dialects | Most dialects | No | No |

| Loss of final *-z in single-syllable words | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Reduction of weak class III to four relics | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Monophthongization of *ai, *au | Yes | Yes | Yes | Usually | Partial | Partial |

| Diphthongization of *ē, *ō | No | No | Rare | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Final-obstruent devoicing | No | No | No | Yes | Developing | No |

| Loss of initial *h- before consonant | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Developing |

| Loss of initial *w- before consonant | No | No | No | No | Most dialects | Yes |

| High German consonant shift | No | No | No | No | Partial | Yes |

Phonology

The original vowel system of West Germanic was similar to that of Proto-Germanic; note however the lowering of the long front vowels.

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | unrounded | rounded | ||||

| short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| Close | i | iː | u | uː | ||

| Mid | e | eː | o | oː | ||

| Open | æ: | a | aː | |||

The consonant system was also essentially the same as that of Proto-Germanic. Note, however, the particular changes described above, as well as West Germanic gemination.

Morphology

Nouns

The noun paradigms of Proto-West Germanic have been reconstructed as follows:[10]

| Case | Nouns in -a- (m.) | Nouns in -ja- | Nouns in -ija- | Nouns in -a- (n.) | Nouns in -ō- | Nouns in -i- | Nouns in -u- | Nouns in -u- (n.) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| Nominative | *dagă | *dagō, -ōs | *harjă | *harjō, -ōs | *hirdijă | *hirdijō, -ijōs | *joką | *joku | *gebu | *gebō | *gasti | *gastī | *sunu | *suniwi, -ō | *fehu | (?) |

| Vocative | *dag | *hari | *hirdī | |||||||||||||

| Accusative | *dagą | *dagą̄ | *harją | *harją̄ | *hirdiją | *hirdiją̄ | *gebā | *gebā | *gastį | *gastį̄ | *sunų | *sunų̄ | ||||

| Genitive | *dagas | *dagō | *harjas | *harjō | *hirdijas | *hirdijō | *jokas | *jokō | *gebā | *gebō | *gastī | *gastijō | *sunō | *suniwō | *fehō | |

| Dative | *dagē | *dagum | *harjē | *harjum | *hirdijē | *hirdijum | *jokē | *jokum | *gebē | *gebōm | *gastim | *suniwi, -ō | *sunum | *fehiwi, -ō | ||

| Instrumental | *dagu | *harju | *hirdiju | *joku | *gebu | *sunu | *fehu | |||||||||

West Germanic vocabulary

The following table compares a number of Frisian, English, Dutch and German words with common West Germanic (or older) origin. The grammatical gender of each term is noted as masculine (m.), feminine (f.), or neuter (n.) where relevant.

| West Frisian | English | Scots | Dutch | German | Old English | Old High German | Proto-West-Germanic[11] | Proto-Germanic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kaam | comb | kaim | kam m. | Kamm m. | camb m. | camb m. | kąbă [see inscription of Erfurt-Frienstedt], *kambă m. | *kambaz m. |

| dei | day | day | dag m. | Tag m. | dæġ m. | tag m. | *dagă m. | *dagaz m. |

| rein | rain | rain | regen m. | Regen m. | reġn m. | regan m. | *regnă m. | *regnaz m. |

| wei | way | wey | weg m. | Weg m. | weġ m. | weg m. | *wegă m. | *wegaz m. |

| neil | nail | nail | nagel m. | Nagel m. | næġel m. | nagal m. | *naglă m. | *naglaz m. |

| tsiis | cheese | cheese | kaas m. | Käse m. | ċēse, ċīese m. | chāsi, kāsi m. | *kāsī m. | *kāsijaz m. (late Proto-Germanic, from Latin cāseus) |

| tsjerke | church | kirk | kerk f. | Kirche f. | ċiriċe f. | chirihha, *kirihha f. | *kirikā f. | *kirikǭ f. (from Ancient Greek kuriakón "belonging to the lord") |

| sibbe | sibling[note 1] | sib | sibbe f. | Sippe f. | sibb f. "kinship, peace" | sippa f., Old Saxon: sibbia | sibbju, sibbjā f. | *sibjō f. "relationship, kinship, friendship" |

| kaai f. | key | key | sleutel m. | Schlüssel m. | cǣġ(e), cǣga f. "key, solution, experiment" | sluzzil m. | *slutilă m., *kēgă f. | *slutilaz m. "key"; *kēgaz, *kēguz f. "stake, post, pole" |

| ha west | have been | hae(s) been | ben geweest | bin gewesen | ||||

| twa skiep | two sheep | twa sheep | twee schapen n. | zwei Schafe n. | twā sċēap n. | zwei scāfa n. | *twai skēpu n. | *twai(?) skēpō n. |

| hawwe | have | hae | hebben | haben | habban, hafian | habēn | *habbjană | *habjaną |

| ús | us | us | ons | uns | ūs | uns | *uns | *uns |

| brea | bread | breid | brood n. | Brot n. | brēad n. "fragment, bit, morsel, crumb" also "bread" | brōt n. | *braudă m. | *braudą n. "cooked food, leavened bread" |

| hier | hair | hair | haar n. | Haar n. | hēr, hǣr n. | hār n. | *hǣră n. | *hērą n. |

| ear | ear | ear | oor n. | Ohr n. | ēare n. < pre-English *ǣora | ōra n. | *aura < *auza n. | *auzǭ, *ausōn n. |

| doar | door | door | deur f. | Tür f. | duru f. | turi f. | *duru f. | *durz f. |

| grien | green | green | groen | grün | grēne | gruoni | *grōnĭ | *grōniz |

| swiet | sweet | sweet | zoet | süß | swēte | s(w)uozi (< *swōti) | *swōtŭ | *swōtuz |

| troch | through | throu | door | durch | þurh | duruh | *þurhw | |

| wiet | wet | weet/wat | nat | nass | wǣt | naz (< *nat) | *wǣtă / *nată | *wētaz / *nataz |

| each | eye | ee | oog n. | Auge n. | ēaġe n. < pre-English *ǣoga | ouga n. | *auga n. | *augō n. |

| dream | dream | dream | droom m. | Traum m. | drēam m. "joy, pleasure, ecstasy, music, song" | troum m. | *draumă m. | *draumaz (< *draugmaz) m. |

| stien | stone | stane | steen m. | Stein m. | stān m. | stein m. | *staină m. | *stainaz m. |

| bed | bed | bed | bed n. | Bett n. | bedd n. | betti n. | *badjă n. | *badją n. |

Other words, with a variety of origins:

| West Frisian | English | Scots | Dutch | German | Old English | Old High German | Proto-West-Germanic[11] | Proto-Germanic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tegearre | together | thegither | samen tezamen | zusammen | tōgædere samen tōsamne | saman zisamane | *tōgadur *samana | |

| hynder | horse | horse | paard n. ros n. (dated) | Pferd n. / Ross n. | hors n. eoh m. | (h)ros n. / pfarifrit n. / ehu- (in compositions) | *hrussă n. / *ehu m. | *hrussą n., *ehwaz m. |

Note that some of the shown similarities of Frisian and English vis-à-vis Dutch and German are secondary and not due to a closer relationship between them. For example, the plural of the word for "sheep" was originally unchanged in all four languages and still is in some Dutch dialects and a great deal of German dialects. Many other similarities, however, are indeed old inheritances.

Notes

- Original meaning "relative" has become "brother or sister" in English.

References

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "West Germanic". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Robinson (1992): p. 17-18

- Kuhn, Hans (1955–56). "Zur Gliederung der germanischen Sprachen". Zeitschrift für deutsches Altertum und deutsche Literatur. 86: 1–47.

- Robinson, Orrin W. (1992). Old English and Its Closest Relatives. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2221-8.

- But see Cercignani, Fausto, Indo-European ē in Germanic, in «Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung», 86/1, 1972, pp. 104–110.

- Ringe, Don. 2006: A Linguistic History of English. Volume I. From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic, Oxford University Press, p. 213-214.

- H. F. Nielsen (1981, 2001), G. Klingenschmitt (2002) and K.-H. Mottausch (1998, 2011)

- Wolfram Euler: Das Westgermanische – von der Herausbildung im 3. bis zur Aufgliederung im 7. Jahrhundert — Analyse und Rekonstruktion (West Germanic: From its Emergence in the 3rd Century to its Split in the 7th Century: Analyses and Reconstruction). 244 p., in German with English summary, London/Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-9812110-7-8.

- Graeme Davis (2006:154) notes "the languages of the Germanic group in the Old period are much closer than has previously been noted. Indeed it would not be inappropriate to regard them as dialects of one language. They are undoubtedly far closer one to another than are the various dialects of modern Chinese, for example. A reasonable modern analogy might be Arabic, where considerable dialectical diversity exists but within the concept of a single Arabic language." In: Davis, Graeme (2006). Comparative Syntax of Old English and Old Icelandic: Linguistic, Literary and Historical Implications. Bern: Peter Lang. ISBN 3-03910-270-2.

- Ringe and Taylor. The Development of Old English. Oxford University Press. pp. 114–115.

- sources: Ringe, Don / Taylor, Ann (2014) and Euler, Wolfram (2013), passim.

Bibliography

- Adamus, Marian (1962). On the mutual relations between Nordic and other Germanic dialects. Germanica Wratislavensia 7. 115–158.

- Bammesberger, Alfred (Ed.) (1991), Old English Runes and their Continental Background. Heidelberg: Winter.

- Bammesberger, Alfred (1996). The Preterite of Germanic Strong Verbs in Classes Fore and Five, in "North-Western European Language Evolution" 27, 33–43.

- Bremmer, Rolf H., Jr. (2009). An Introduction to Old Frisian. History, Grammar, Reader, Glossary. Amsterdam / Philadelphia: Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Euler, Wolfram (2002/03). "Vom Westgermanischen zum Althochdeutschen" (From West Germanic to Old High German), Sprachaufgliederung im Dialektkontinuum, in Klagenfurter Beiträge zur Sprachwissenschaft, Vol. 28/29, 69–90.

- Euler, Wolfram (2013) Das Westgermanische – von der Herausbildung im 3. bis zur Aufgliederung im 7. Jahrhundert – Analyse und Rekonstruktion (West Germanic: from its Emergence in the 3rd up until its Dissolution in the 7th Century CE: Analyses and Reconstruction). 244 p., in German with English summary, Verlag Inspiration Un Limited, London/Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-9812110-7-8.

- Härke, Heinrich (2011). Anglo-Saxon Immigration and Ethnogenesis, in: „Medieval Archaeology” No. 55, 2011, pp. 1–28.

- Hilsberg, Susan (2009). Place-Names and Settlement History. Aspects of Selected Topographical Elements on the Continent and in England, Magister Theses, Universität Leipzig.

- Klein, Thomas (2004). "Im Vorfeld des Althochdeutschen und Altsächsischen" (Prior to Old High German and Old Saxon), in Entstehung des Deutschen. Heidelberg, 241–270.

- Kortlandt, Frederik (2008). Anglo-Frisian, in „North-Western European Language Evolution“ 54/55, 265 – 278.

- Looijenga, Jantina Helena (1997). Runes around the North Sea and on the Continent AD 150–700; Text & Contents. Groningen: SSG Uitgeverij.

- Friedrich Maurer (1942), Nordgermanen und Alemannen: Studien zur germanischen und frühdeutschen Sprachgeschichte, Stammes- und Volkskunde, Strassburg: Hüneburg.

- Mees, Bernard (2002). The Bergakker inscription and the beginnings of Dutch, in „Amsterdamer Beiträge zur älteren Germanistik” 56, 23–26.

- Mottausch, Karl-Heinz (1998). Die reduplizierenden Verben im Nord- und Westgermanischen: Versuch eines Raum-Zeit-Modells, in "North-Western European Language Evolution" 33, 43–91.

- Nielsen, Hans F. (1981). Old English and the Continental Germanic languages. A Survey of Morphological and Phonological Interrelations. Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachwissenschaft. (2nd edition 1985)

- Nielsen, Hans Frede. (2000). Ingwäonisch. In Heinrich Beck et al. (eds.), Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (2. Auflage), Band 15, 432–439. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Page, Raymond I. (1999). An Introduction to English Runes, 2. edition. Woodbridge: Bogdell Press.

- Page, Raymond I. (2001). Frisian Runic Inscriptions, in Horst Munske et al., "Handbuch des Friesischen". Tübingen, 523–530.

- Ringe, Donald R. (2012). Cladistic principles and linguistic reality: the case of West Germanic. In Philomen Probert and Andreas Willi (eds.), Laws and Rules on Indo-European, 33–42. Oxford.

- Ringe, Donald R. and Taylor, Ann (2014). The Development of Old English – A Linguistic History of English, vol. II, 632p. ISBN 978-0199207848. Oxford.

- Robinson, Orrin W. (1992). Old English and Its Closest Relatives. A Survey of the Earliest Germanic Languages. Stanford University Press.

- Seebold, Elmar (1998). "Die Sprache(n) der Germanen in der Zeit der Völkerwanderung" (The Language(s) of the Germanic Peoples during the Migration Period), in E. Koller & H. Laitenberger, Suevos – Schwaben. Das Königreich der Sueben auf der Iberischen Halbinsel (411–585). Tübingen, 11–20.

- Seebold, Elmar (2006). "Westgermanische Sprachen" (West Germanic Languages), in Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde 33, 530–536.

- Stifter, David (2009). "The Proto-Germanic shift *ā > ō and early Germanic linguistic contacts", in Historische Sprachforschung 122, 268–283.

- Stiles, Patrick V. (1995). Remarks on the “Anglo-Frisian” thesis, in „Friesische Studien I”. Odense, 177–220.

- Stiles, Patrick V. (2004). Place-adverbs and the development of Proto-Germanic long *ē1 in early West Germanic. In Irma Hyvärinen et al. (Hg.), Etymologie, Entlehnungen und Entwicklungen. Mémoires de la Soc. Néophil. de Helsinki 63. Helsinki. 385–396.

- Stiles, Patrick V. (2013). The Pan-West Germanic Isoglosses and the Subrelationships of West Germanic to Other Branches. In Unity and Diversity in West Germanic, I. Special issue of NOWELE 66:1 (2013), Nielsen, Hans Frede and Patrick V. Stiles (eds.), 5 ff.

- Voyles, Joseph B. (1992). Early Germanic Grammar: pre-, proto-, and post-Germanic Language. San Diego: Academic Press