Richard Serra

Richard Serra (born November 2, 1938) is an American artist involved in the Process Art Movement. He lives and works in Tribeca, New York and on the North Fork, Long Island.

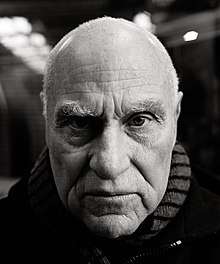

Richard Serra | |

|---|---|

Richard Serra portrayed by Oliver Mark, Siegen 2005 | |

| Born | November 2, 1938 San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | University of California, Berkeley (attended) University of California, Santa Barbara (B.A. 1961) Yale University (B.F.A. 1962, M.F.A. 1964) |

| Movement | Process Art |

| Spouse(s) | Clara Weyergraf

( m. after 1981) |

Early life and education

Serra was born on November 2, 1938, in San Francisco, the second of three sons.[1][2] His father, Tony, was a Spanish native of Mallorca who worked as a candy factory foreman and in steel mills.[3] Serra described the San Francisco shipyard where his father worked as a pipefitter as an important influence on his work: "All the raw material that I needed is contained in the reserve of this memory which has become a recurring dream."[4] His mother, Gladys Feinberg, was born in Los Angeles to Russian Jewish immigrants from Odessa[5][6][7][8] and later worked as a housewife.[9]

Serra studied English literature at the University of California, Berkeley in 1957 before transferring to the University of California, Santa Barbara, graduating with a B.A. in the subject in 1961.[10][11][12] At UCSB, he studied art with Howard Warshaw and Rico Lebrun. Serra helped support himself by working in steel mills, labor that strongly influenced his later work. He studied painting in the M.F.A. program at the Yale School of Art between 1961 and 1964. Fellow Yale alumni of the 1960s include the painters, photographers, and sculptors Brice Marden, Chuck Close, Nancy Graves, and Robert Mangold. Serra has said he has taken most of his inspiration from the artists who taught there, including Philip Guston, composer Morton Feldman, and painter Josef Albers.[2]

While at Yale, Serra proofed Albers's book Interaction of Color (1963).[13] In 1964, after he received his M.F.A., he was awarded a traveling fellowship from Yale and went to Paris. He was awarded a Fulbright fellowship the following year in Florence.[14] Since then he has lived in New York. In New York, his circle of friends has included Carl Andre, Walter De Maria, Eva Hesse, Sol LeWitt, and Robert Smithson.[15] At one point, to fund his art, Serra started a furniture-removals business, Low-Rate Movers,[2] and employed Chuck Close, Philip Glass, Spalding Gray, and others.[16]

Work

Early sculptures

In 1966, Serra made his first sculptures out of nontraditional materials such as fiberglass and rubber.[15] Serra's earliest work was abstract and process-based made from molten lead hurled in large splashes against the wall of a studio or exhibition space. In 1967 and 1968 he compiled a list of infinitives, titled "Verb List," that served as catalysts for subsequent work: "to hurl" suggested the hurling of molten lead into crevices between wall and floor; "to roll" led to the rolling of the material into dense, metal logs.[17] In 1969, Jasper Johns invited Serra to create one of his splash pieces in his studio on Houston Street.[9]

Serra began in 1969 to be primarily concerned with the cutting, propping or stacking of lead sheets, rough timber, etc., to create structures, some very large, supported only by their own weight.[18] His "Prop" pieces from the late 1960s are arranged so that weight and gravity balance lead rolls and sheets. Cutting Device: Base Plate Measure (1969) consists of an assemblage of heterogeneous materials (lead, wood, stone and steel) into which two parallel cuts have been made and the results strewn around in a chance configuration.[19] In Malmo Role (1984), a four-foot-square steel plate, one and a half inches thick, bisects a corner of the room and is prevented from falling by a short cylindrical prop wedged into the corner of the walls.[20]

Still, he is better known for his minimalist constructions from large rolls and sheets of metal (COR-TEN steel). Many of these pieces are self-supporting and emphasize the weight and nature of the materials. Rolls of lead are designed to sag over time.[21]

Large steel sculptures

.jpg)

Around 1970, Serra shifted his activities outdoors, focusing on large-scale site-specific sculpture.[5] Serra often constructs site-specific installations, frequently on a scale that dwarfs the observer. His site-specific works challenge viewers' perception of their bodies in relation to interior spaces and landscapes, and his work often encourages movement in and around his sculptures.[4][22] Most famous is the "Torqued Ellipse" series, which began in 1996 as single elliptical forms inspired by the soaring space of the early 17th century Baroque church San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane in Rome.[23] Made of huge steel plates bent into circular sculptures with open tops, they rotate upward as they lean in or out.[24]

Serra usually begins a sculpture by making a small maquette (or model) from flat plates at an inch-to-foot ratio: a 40-foot piece will start as a 40-inch model.[25] He often makes these models in lead as it is "very malleable and easy to rework continuously." He then consults a structural engineer, who specifies how the piece should be made to retain its balance and stability.[5] The steel pieces are fabricated in Wetzlar, Germany.[9] The steel he uses takes about 8–10 years to develop its characteristic dark, even patina of rust. Once the surface is fully oxidized, the color will remain relatively stable over the piece's life.[5]

Serra's first larger commissions were mostly realized outside the United States. Shift (1970–72) consists of six walls of concrete zigzag across a grassy hillside in King City, Ontario. Spin Out (1972–73), a trio of steel plates facing one another, is situated on the grounds of the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, the Netherlands.[5] (Schunnemunk Fork (1991), a work similar to that of his in the Netherlands can be found in Storm King Art Center in Upstate New York.)[26] Part of a series works involving round steelplates, Elevation Circles: In and Out (1972–77) was installed at Schlosspark Haus Weitmar in Bochum, Germany.[27]

For documenta VI (1977), Serra designed Terminal, four 41-foot-tall trapezoids that form a tower, situated in front of the main exhibition venue. After long negotiations, accompanied by violent protests, Terminal was purchased by the city of Bochum and finally installed at the city's train station in 1979.[28] Carnegie (1984–85), a 39-foot-high vertical shaft outside the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, received high praise.[5] Similar sculptures, like Fulcrum (1987), Axis (1989), and Torque (1992), were later installed in London's Broadgate, at Kunsthalle Bielefeld, and at Saarland University, respectively. Initially located in the French town of Puteaux, Slat (1985) consists of five steel plates – four trapezoidal and one rectangular – each one roughly 12 feet wide and 40 feet tall,[29] that lean on one another to form a tall, angular tepee. Already in 1989 vandalism and graffiti prompted that town's mayor to remove it, and only in December 2008, after almost 20 years in storage, Slat was re-anchored in La Défense. Because of its weight, officials chose to ground it in a traffic island behind the Grande Arche.[30]

In 1979, Wright's Triangle was installed on Western Washington University's campus, as an addition to the Western Washington University Public Sculpture Collection. The triangular shaped piece was installed at an intersection of three paths that run through the middle of the campus. Its placement and structure allows viewers to walk around and through the piece, hopefully presenting ideas of confrontation, separation, and union.

In 1981, Serra installed Tilted Arc, a 3.5 meter high arc of steel in the Federal Plaza in New York City. There was controversy over the installation from day one, largely from workers in the buildings surrounding the plaza who complained that the steel wall obstructed passage through the plaza. A public hearing in 1985 voted that the work should be moved, but Serra argued the sculpture was site specific and could not be placed anywhere else. Serra famously issued an often-quoted statement regarding the nature of site-specific art when he said, "To remove the work is to destroy it." Eventually on March 15, 1989, the sculpture was dismantled by federal workers and consigned to a New York warehouse. In 1999, they were moved to a storage space in Maryland.[2][31] William Gaddis satirized these events in his 1994 novel A Frolic of His Own.

Serra continues to produce large-scale steel structures for sites throughout the world, and has become particularly renowned for his monumental arcs, spirals, and ellipses, which engage the viewer in an altered experience of space. In particular, he has explored the effects of torqued forms in a series of single and double-torqued ellipses.[32] He was invited to create a number of artworks in France: Philibert et Marguerite in the cloister of the Musée de Brou at Bourg-en-Bresse (1985); Threats of Hell (1990) at the CAPC (Centre d'arts plastiques contemporains de Bordeaux) in Bordeaux; Octagon for Saint Eloi (1991) in the village of Chagny in Burgundy; and Elevations for L'Allée de la Mormaire in Grosrouvre (1993).[33] Alongside those works, Serra designed a series of forged pieces including Two Forged Rounds for Buster Keaton (1991); Snake Eyes and Boxcars (1990-1993), six pairs of forged hyper-dense Cor-Ten steel blocks;,[34] Ali-Frazier (2001), two forged blocks of weatherproof steel; and Santa Fe Depot (2006).[35]

In 2000, he installed Charlie Brown, a 60-foot-tall sculpture in atrium of the new Gap Inc. headquarters in San Francisco. Working with spheroid and toroid sections for the first time, Betwixt the Torus and the Sphere (2001) and Union of the Torus and the Sphere (2001) introduced entirely new shapes into Serra's sculptural vocabulary.[32] Wake (2003) was installed at the Olympic Sculpture Park in Seattle, with its five pairs of forms measuring 14 feet high, 48 feet long and six feet wide apiece. Each of these five closed volumes is composed of two toruses, with the profile of a solid, vertically flattened S.[36]

Named for the late Joseph Pulitzer Jr. (1913-1993), the rolled-steel elliptical sculpture Joe (2000)[37] is the first in Serra's series of "Torqued Spirals".[38] It is, The 42.5-ton piece T.E.U.C.L.A., another part of the "Torqued Ellipse" series and Serra's first public sculpture in Southern California, was installed in 2006 in the plaza of UCLA's Eli and Edythe Broad Art Center.[24] That same year, the Segerstrom Center for the Arts in Costa Mesa installed Serra's Connector, a 66-foot-tall towering sculpture on its plaza.[24]

_by_Richard_Serra_--_Glenstone_Museum_Potomac_(MD)_October_2018_(44082823230).jpg)

Another famous work of Serra's is the mammoth sculpture Snake, a trio of sinuous steel sheets creating a curving path, permanently located in the largest gallery of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao. In 2005, the museum mounted an exhibition of more of Serra's work, incorporating Snake into a collection entitled The Matter of Time. The whole work consists of eight sculptures measuring between 12 and 14 feet in height and weighing from 44 to 276 tons.[39] Already in 1982-84, he had installed the permanent work La palmera in the Plaça de la Palmera in Barcelona. He has not always fared so well in Spain, however; also in 2005, the Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid announced that the 38-tonne sculpture Equal-Parallel/Guernica-Bengasi (1986) had been "mislaid".[40] In 2008, a duplicate copy was made by the artist and displayed in Madrid.[41]

In spring 2005, Serra returned to San Francisco to install his first public work, Ballast (2004), in that city (previous negotiations for a commission fell through) – two 50-foot steel plates in the main open space of the new University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) campus.

In 2008, Serra showed his installation Promenade, a series of five colossal steel sheets placed at 100-foot intervals through in the Grand Palais as part of the Monumenta exhibition; each sheet weighed 75 tons and was 17 meters in height.[42] Serra was the second artist, after Anselm Kiefer, to be invited to fill the 13,500 m² nave of the Grand Palais with works created specially for the event.[43][44][45]

In December 2011, Serra unveiled his sculpture 7 in Doha, Qatar.[46] The sculpture, located at the plaza in Doha harbour, is composed of seven steel sheets and is 80-foot high. The sculpture was commissioned by the Qatar Museums Authority.[47] In March 2014, Serra's East-West/West-East, a site-specific sculpture located at a remote desert location stretching more than a half-mile through Qatar's Brouq nature reserve, was unveiled.[48] In 2015, the sculptor's monumental work Equal, composed of eight blocks of steel and exhibited that year at David Zwirner in New York, was acquired by The Museum of Modern Art.[49]

In the past Serra has dedicated work to Charlie Chaplin, Greta Garbo, Marilyn Monroe, Buster Keaton, the German filmmaker Rainer Werner Fassbinder and the art critic David Sylvester.[2]

in 2019, Larry Gagosian opened Serra's atworks at several of his galleries around New York. Alongside his standard steel sculptures, this also featured two floors of drawings entitled Triptychs and Diptychs at Madison Avenue.[50][51]

Memorials

For the city of Goslar, Serra designed Gedenkstätte Goslar (1981). In 1987, he created Berlin Junction as a memorial to those who lost their lives to the Nazis' genocide program. First shown at the Martin-Gropius-Bau, the sculpture was installed permanently at the Berliner Philharmonie in 1988. For the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, he designed Gravity, a 10-inch-thick, 10-foot-square standing slab of steel, in 1993.[52] After initially joining with architect Peter Eisenmann to submit a design for Berlin's Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, Serra declined the project for "personal and professional reasons" in 1998.[53]

Performance and video art

Serra was one of the four performers in the premiere of the Steve Reich piece Pendulum Music on May 27, 1969 at the Whitney Museum of American Art. The other performers were Michael Snow, James Tenney and Bruce Nauman.[54]

Hand Catching Lead (1968) was Serra's first film and features a single shot of a hand in an attempt to repeatedly catch chunks of material dropped from the top of the frame.[55] He also produced the 1973 short video Television Delivers People, a critique of the corporate mass media with elevator music as the soundtrack. In Boomerang (1974), Serra taped Nancy Holt as she talks and hears her words played back to her after they have been delayed electronically. The host of Serra's 1974 parody game show, Prisoners' Dilemma, explains that the loser will spend six hours alone in a basement.

Railroad Turnbridge (1976) is a series of shots taken on the Burlington and Northern bridge over the Willamette River near Portland, Oregon, as it opens to let a ship pass. In Steelmill/Stahlwerk, a 1979 documentary made in collaboration with Clara Weyergraf, Serra explores the physical construction of an art piece and at the same time examines the lives of the steelmill. These films can be viewed in a room off the Arcelor gallery in the Guggenheim museum in Bilbao.[56]

Serra appears in Matthew Barney's 2002 film Cremaster 3 as Hiram Abiff ("the architect"), and later as himself in the climactic The Order section – the only part of a Cremaster film commercially available on DVD.[57]

Prints and drawings

Since 1971, Serra has made large-scale drawings on handmade Hiromi paper or Belgian linen using various techniques. In the early 1970s he drew primarily with charcoal, and lithographic crayon on paper.[58] His primary drawing material has been the paintstick, a wax-like grease crayon. Serra melts several paintsticks to form large pigment blocks. Drawings After Circuit (1972) followed an installation for Documenta of four huge steel plates (8 by 24 feet each) jutting in from the corners of a room, stopping short of meeting in the center.[59]

In the mid-1970s, Serra made his first "Installation Drawings" — monumental works on canvas or linen pinned directly to the wall and thickly covered with black paintstick, such as Abstract Slavery (1974), Taraval Beach (1977), Pacific Judson Murphy (1978), and Blank (1978). The drawings Serra has executed since the 1980s continue the experiments with innovative techniques but are less monumental physically.[60] In the late 1980s, he explored how to further articulate the tension of weight and gravity by placing pairs of overlapping sheets of paper saturated with paintstick in horizontal and vertical compositions, using a mesh screen as an intermediary between the gesture and the transfer of pigment to the paper.[58]

At the 2006 Whitney Biennial, Serra showed a simple litho crayon drawing of an Abu Ghraib prisoner with the caption "STOP BUSH."[61] Serra also created a variation on Goya's Saturn Devouring His Son featuring George W. Bush's head in place of Saturn's. This was featured prominently in an ad for the website pleasevote.com (now defunct) on the back cover of the July 5, 2004 issue of The Nation.

Exhibitions

Shortly after Serra arrived in New York, Robert Morris invited him to participate in a group show at Castelli Gallery.[9] He had his first solo exhibitions at the Galleria La Salita, Rome, 1966, and in the United States at the Leo Castelli Warehouse, New York. The Pasadena Art Museum organized a solo exhibition of Serra's work in 1970. Serra has since participated in Documentas 5 (1972), 6 (1977), 7 (1982), and 8 (1987), in Kassel, the Venice Biennales of 1984 and 2001, and the Whitney Museum of American Art's Annual and Biennial exhibitions of 1968, 1970, 1973, 1977, 1979, 1981, and 1995.[62] Serra was honored with further solo exhibitions at the Kunsthalle Tübingen, Germany, in 1978; the Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris, in 1984; the Museum Haus Lange, Krefeld, Germany, in 1985; and the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1986. From 1997 to 1998 his Torqued Ellipses (1997) were exhibited at and acquired by the Dia Center for the Arts, New York. In 2005 eight major works by Serra were installed permanently at Guggenheim Museum Bilbao.[63]

In the summer of 2007 the Museum of Modern Art presented a retrospective of Serra's work in New York. Intersection II (1992–1993) and Torqued Ellipse IV (1998) were included in this show along with three new works.[64] The retrospective consisted of 27 of Serra's works, including three large new sculptures made specifically for the second floor of the museum, two works in the garden, and earlier pieces from the 1960s through the 1980s.[65]

Major presentations of Serra's graphic oeuvre include exhibitions at the Bonnefantenmuseum, Maastricht, in 1990; at Serpentine Gallery, London, in 1992; and at Kunsthaus Bregenz, Bregenz, in 2008. Also in 2008, he was invited to take over the Grand Palais in Paris for the bi-annual Monumenta series, with a work consisting of towering steel cenotaphs.[66] In 1980, Serra installed "Elevator, 1980" at Hudson River Museum.[67][68]

In 2011, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Menil Collection hosted a retrospective exhibit focusing on Serra's drawings, tracing the development of his drawing as an art form independent from yet linked to his sculptural practice.[69][70][71][72]

Collections

Serra's work can be found in many international public and private collections, including the Museum of Modern Art and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art,[73] and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Since the early 1970s, Serra has completed many private commissions, most of them funded by European patrons.[5] Private commissions in the United States include sculptures for Eli Broad (No Problem, 1995),[3][74] Jeffrey Brotman,[75] Peggy and Ralph Burnet (To Whom It May Concern, 1995),[76] Gil Freisen, Alan Gibbs (Te Tuhirangi Contour, 1999-2001), Ivan Reitman,[77] Steven H. Oliver (Snake Eyes and Boxcar, 1990–93),[78] Leonard Riggio,[3] Agnes Gund (Iron Mountain Run, 2002)[3] and Mitchell Rales.[77]

In 2006, Colby College acquired 150 prints by Serra, making it the second largest collection of Serra's work outside of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.[79]

Recognition

Serra's work was featured on BBC One in "Imagine ... Richard Serra: Man of Steel" on Tuesday November 25, 2008 which described him as "Sculptor and giant of modern art Richard Serra discusses his extraordinary life and work. A creator of enormous, immediately identifiable steel sculptures that both terrify and mesmerize, Serra believes that each viewer creates the sculpture for themselves by being within it." Contributors include Chuck Close, Philip Glass and Glenn D Lowry, Director of MoMA. He was interviewed at length by the BBC's Alan Yentob.[80]

In 1975, Serra received the Skowhegan Medal for Sculpture. He was awarded the Goslarer Kaiserring in 1981, and in 1991, he won the Wilhem Lehmbruck Prize for Sculpture in Duisburg. In 1993, Serra was elected a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He is also a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the Akademie der Künste (Germany), as well as having been named member of the Orden Pour le Mérite für Wissenschaften und Künste (2002) in Germany and Commandeur de L'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (2008) in France. In 1994, he was honored with the Praemium Imperiale. In 2006 he was elected into the National Academy of Design.[81] Serra has been awarded the Presidentʼs Medal from the Architectural League of New York in 2014, the first time the prize has been given to an artist.[82] In 2015, he was awarded France's premier award, the Insignes de Chevalier de l'Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur at a ceremony in New York.[42]

Serra was awarded honorary degrees of Doctor of Fine Arts by Williams College in 2008; the California College of Arts and Crafts, the Nova Scotia College of Arts and Design, Yale University, and Universidad Pública de Navarra (2009); and by Harvard University in 2010.

In 1980 Serra was invited to the White House and received by Jimmy Carter.[83]

Controversies

Along with the debate surrounding Tilted Arc, Serra's public image has been further affected by two accidents. In November 1971, 34-year-old Raymond Johnson, a laborer installing Serra's Sculpture No. 3 at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, was crushed to death when a two-ton steel plate toppled over on him.[84] A subsequent lawsuit absolved the artist and museum of blame. In October 1989, another worker lost a leg while dismantling a 16-ton Serra sculpture at the Leo Castelli Gallery.[5]

In 2002, an installation titled Vectors was to be built at the California Institute of Technology from the bequest of Eli Broad. The proposed 80-ton piece,[85] to be four steel plates of similar material as Tilted Arc zig-zagging across one of the few green spaces at the university, met significant opposition by the student body and professors as being a "'derivative' rehash of earlier works, or an 'arrogant' piece that [belied] Institute values."[86] The piece was never installed.[85]

Art market

Only a few of Serra's top auction prices are for sculpture; the rest are for his works on paper. In 2001, an untitled, 1984 curved steel wall was sold for $1.2 million at Sotheby's in New York.[87] The current record auction price for a Serra sculpture was paid at Sotheby's in 2008, where 12-4-8, a 1983 work consisting of three steel plates, sold for $1.65 million.[88]

Richard Bellamy director of the Noah Goldowsky Gallery became Serra's first dealership.[89][90] By 1969 Serra was regularly showing his works at the Leo Castelli Gallery and receiving a regular gallery stipend of $500 a month.[5] Galerie m in Bochum, Germany, has represented Serra in Europe since 1975. Gagosian Gallery became the artist's primary dealer in 1991 after opening a space in New York's Soho district. Since 1972, with publisher Gemini G.E.L. in Los Angeles, Serra has released 170 different prints, 120 of them since 1990.[87]

Owners, whether individuals or museums, are prohibited from moving or altering his work without his permission. Moreover, a collector cannot offer a work for sale to another collector without offering it to Serra first.[9]

Personal life

Serra's older brother is the famed San Francisco trial attorney Tony Serra.[91] They have been estranged for almost 40 years, since their mother committed suicide by walking into the Pacific Ocean.[92] Serra was married to artist Nancy Graves from 1965 to 1970.[93] He then married art historian Clara Weyergraf in 1981. Since 1977, Serra and Weyergraf have resided on several floors of a former manufacturing building in Tribeca.[94] Since the late 1970s, they have spent part of the year in an 18th-century farmhouse on a hill above the Northumberland Strait in Inverness County, Nova Scotia, and on the North Fork, Long Island.[95]

According to the Federal Election Commission (FEC), Serra donated $28,000 to the presidential campaign of Hillary Clinton in September 2016.[96]

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Richard Serra. |

- "Richard Serra: California Birth Index, 1905–1995". FamilySearch. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- Sean O'Hagan (October 5, 2008), Man of steel The Guardian.

- Kelly Crow (November 4, 2015), The Reinvented Visions of Richard Serra The Wall Street Journal.

- Seidner, David http://bombsite.com/issues/42/articles/1605, BOMB Magazine Winter, 1993. Retrieved on July 14, 2011.

- Deborah Solomon (October 8, 1989), Our most notorious sculptor New York Times.

- "Richard Serra logra el "Príncipe" por su "audacia" en la creación de espacios". La Nueva España (in Spanish).

- Garden Castro, Jan (1999). "Richard Serra, Man of Steel". Sculpture Magazine. Vol. 18 no. 1. International Sculpture Center.

- Senie, Harriet F. (2002). The tilted arc controversy: dangerous precedent?. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9781452905273.

- Deborah Solomon (August 28, 2019), Richard Serra Is Carrying the Weight of the World The New York Times.

- "Encyclopædia Britannica Biography". Retrieved October 13, 2014.

- "About Richard Serra". Retrieved October 13, 2014.

- "Richard Serra's First Retrospective Exhibition of Drawings Opens at Metropolitan Museum on April 13". Metmuseum.org. April 8, 2014. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- "Richard Serra". Guggenheim Collection. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012.

- ""Drawings - Work Comes Out of Work" show at Kunsthaus Bregenz in 2008". Kunsthaus-bregenz.at. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 14, 2008. Retrieved January 11, 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Karen Rosenberg (May 17, 2007), Richard’s Arc New York.

- Richard Serra, Right Angle Prop (1969) Guggenheim Collection.

- Richard Serra Tate.

- John Russell (February 28, 1986), Startling Sculpture from Richard Serra New York Times.

- Ken Johnson (May 17, 2002), Richard Serra -- 'Prop Sculptures: 1969-87' New York Times.

- "Steel yourself: Richard Serra's monumental sculptures". The Independent. October 13, 2008. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- Cooke, Lynne, "Thinking on your feet: Richard Serra's Sculptures in Landscape" in Richard Serra Sculpture: Forty Years, ed. McShine and Cooke, (NY: MoMA; London: Thames and Hudson) 2007, p. 80.

- Suzanne Muchnich (September 6, 1998), An Ironclad Visionary Los Angeles Times.

- Suzanne Muchnich (March 26, 2006), Sculpting his steely vision Los Angeles Times.

- Andrew M. Goldstein (September 28, 2011), "You Have to Make a Choice": A Q&A With Richard Serra on His New Sculptures at Gagosian ARTINFO.

- "Schunnemunk Fork details at Storm King". Archived from the original on July 15, 2010. Retrieved August 12, 2007.

- Richard Serra Galerie m, Bochum.

- Deborah Solomon (October 8, 1989), Our most notorious sculptor New York Times.

- Michael Brenson (November 3, 1985), Richard Serra Works Find A Warm Welcome in France The New York Times.

- Serra Sculpture Reinstalled in Paris ARTINFO, December 17, 2008.

- "Tilted Arc". Nero Magazine.

- Richard Serra: Torqued Spirals, Toruses and Spheres, October 18 - December 15, 2001 Gagosian Gallery, New York.

- Richard Serra, May 7 - June 15, 2008 Archived December 30, 2010, at the Wayback Machine MONUMENTA, Grand Palais, Paris.

- Richard Serra Oliver Ranch Foundation, Sonoma County.

- Robert L. Pincus (December 10, 2006), Heavy metal U-T San Diego.

- Richard Serra: Wake Blindspot Catwalk Vice-Versa, September 20 – October 25, 2003 Gagosian Gallery, New York.

- John Russell (October 30, 2001), An Unmuseum Guaranteed to Be Uncrowded The New York Times.

- Richard Serra, Joe (2000) Pulitzer Arts Foundation.

- Jeannie Rosenfeld (October 1, 2006), Artist's Dossier: Richard Serra, BLOUINARTINFO, retrieved April 28, 2008

- "Madrid 'mislays' Serra sculpture". BBC. January 19, 2006. Retrieved March 18, 2016.

- "Return of the lost Serra: Missing 38-tonne sculpture is "back"". The Art Newspaper. December 2008. (dead link November 27, 2018)

- Burns, Charlotte (May 29, 2015). "Richard Serra due to receive the French government's highest honour". The Art Newspaper. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015.

- Wainwright, Lisa S. "Richard Serra". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- "Monumenta". RMN - Grand Palais. RMN - Grand Palais. Archived from the original on March 13, 2015. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- Erlanger, Steven (May 7, 2008). "Serra's Monumental Vision, Vertical Edition". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- Hartvig, Nicolai (December 20, 2011). ""7" Up: Richard Serra Unveils New Sculpture in Doha". www.blouinartinfo.com.

- Merrick, Jay (December 28, 2011). "The magnificent '7' adds an edge to Doha's gloss". The Independent.

- Georgina Adams (April 4, 2014), Qatar celebrates Richard Serra Financial Times.

- Alex Greenberger (June 12, 2015), MoMA Acquires Richard Serra's New Sculpture at David Zwirner.

- Peers, Alexandra. "Richard Serra Stuns Yet Again With a Blockbuster Trio of Gagosian Shows". Architectural Digest. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- Solomon, Deborah (August 28, 2019). "Richard Serra Is Carrying the Weight of the World". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- "The Art". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on April 6, 2004.

- Edmund L. Andrews (June 4, 1998), Serra Quits Berlin's Holocaust Memorial Project New York Times.

- Fox and Godfrey. "Harmonious Life: In conversation with Steve Reich". Frieze. Retrieved October 5, 2012.

- UbuWeb Film: Hand Catching Lead (1968)

- "Richard Serra". April 29, 2013. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

- Ramlow, Todd R. "Cremaster 3 (2002)". < PopMatters. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- Richard Serra Drawing: A Retrospective, March 2 – June 10, 2012 Archived June 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Menil Collection, Houston.

- Leah Ollman (May 1, 2011), Richard Serra in drawing mode Los Angeles Times.

- Richard Serra Drawing: A Retrospective, April 13 – August 28, 2011 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

- "Whitney Biennial 2006: Richard Serra". Whitney.org. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- Artist Biography: Richard Serra Archived November 22, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Dia Art Foundation, New York.

- Richard Serra Guggenheim Museum.

- Details of 2007 Moma Retrospective Archived July 6, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Robert Ayers (April 11, 2007), Richard Serra, ARTINFO, retrieved April 28, 2008

- Monumenta Minor Sights

- Raynor, Vivien (February 15, 1981). "Art; BUT JUST WHAT DOES ALL THIS MEAN?". New York Times.

- Serra, Richard; Weyergraf-Serra, Clara (March 25, 1980). Richard Serra, Interviews, Etc., 1970-1980. Hudson River Museum – via Google Books.

- "Richard Serra's First Retrospective Exhibition of Drawings Opens at Metropolitan Museum on April 13". The Met. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. April 8, 2011. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- "First-Ever Retrospective of Richard Serra's Drawings Offers Chance To See Artist's Work From Entirely New Angle". SFMOMA. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. July 25, 2011. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- "Richard Serra Drawing: A Retrospective". Menil. The Menil Collection. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- MacAdam, Barbara A. (April 1, 2011). "Pushing the Boundaries of Drawing". ArtNews. Art Media ARTNEWS, llc. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- Suzanne Muchnic (January 13, 2008), A sculptural ramble with Richard Serra Los Angeles Times.

- Kevin West (June 2009), Art Party Archived June 30, 2012, at the Wayback Machine W Magazine.

- Hilarie M. Sheets (March 27, 2009), Decking the Halls - Susan and Jeff Brotman have hung their stellar collection in a light-filled house, Art+Auction.

- Julie Brener (March 27, 2009), Minnesota Modern, Art+Auction.

- Bob Colacello (April 1995), The Art of the Deal Vanity Fair.

- Kenneth Baker (March 27, 2009), The Man Who Can, Art+Auction.

- Colby College Receives Major Gift of Richard Serra Works on Paper, June 1, 2006 Colby College, Waterville, Maine.

- "BBC One - imagine..., Autumn 2008, Richard Serra: Man of Steel". BBC. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

- "National Academicians". National Academy Museum. Archived from the original on March 20, 2016.

- Robin Pogrebin (April 23, 2014), Richard Serra Wins Architectural League Prize New York Times.

- Peter Carlson (April 1, 1985), A Rusty Eyesore or a Work of Art? Sculptor Richard Serra Defends His Controversial Tilted Arc People.

- Buffenstein, Alyssa (May 5, 2016). "When Sculptures Kill..." Vice. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- Bettijane Levine (November 16, 2002), Caltech rejects Serra's massive wall sculpture Los Angeles Times.

- Caltech (October 17, 2002), Serra sculpture debate continues, Caltech, archived from the original on February 4, 2009, retrieved August 24, 2008

- Jeannie Rosenfeld (May 6, 2007), Artist's Dossier: Richard Serra BLOUINARTINFO.

- Catherine Hickley (May 12, 2010), Richard Serra Wins Art Prize Awarded by Heir to Spanish Throne Bloomberg.

- New Yorker, Man of Steel

- Annette Grant (June 5, 2005), How to Install a 48-Foot, 12-Ton Orange Steel Giant New York Times.

- Liberatore, Paul (December 7, 2010). "Drawn to the drama". Marin Independent Journal.

- Weil, Elizabeth (October 13, 2015). "Shrimp Boy's Day in Court". The New York Times. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- Roberta Smith (October 24, 1995), Nancy Graves, 54, Prolific Post-Minimalist Artist New York Times.

- Christopher Gray (September 27, 1998 ), Streetscapes/Duane Park in TriBeCa; From Butter and Eggs to the Home of Haute Cuisine New York Times.

- Deborah Solomon (October 8, 1989), Our Most Notorious Sculptor New York Times.

- Ben Luke (November 3, 2016), Artists raise millions for Hillary Clinton Archived November 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine The Art Newspaper.

| Library resources about Richard Serra |

| By Richard Serra |

|---|

![]()