Tree shaping

Tree shaping (also known by several other alternative names) uses living trees and other woody plants as the medium to create structures and art. There are a few different methods[2] used by the various artists to shape their trees, which share a common heritage with other artistic horticultural and agricultural practices, such as pleaching, bonsai, espalier, and topiary, and employing some similar techniques. Most artists use grafting to deliberately induce the inosculation of living trunks, branches, and roots, into artistic designs or functional structures.

Tree shaping has been practiced for at least several hundred years, as demonstrated by the living root bridges built and maintained by the Khasi people of India. Early 20th century practitioners and artisans included banker John Krubsack, Axel Erlandson with his famous circus trees, and landscape engineer Arthur Wiechula. Contemporary designers include "Pooktre" artists Peter Cook and Becky Northey, "arborsculpture" artist Richard Reames, and furniture designer Dr Chris Cattle, who grows "grownup furniture".

History

Some species of trees exhibit a botanical phenomenon known as inosculation (or self-grafting); whether among parts of a single tree or between two or more individual specimens of the same (or very similar) species. Trees exhibiting this behavior are called inosculate trees.[3]

The living root bridges of Cherrapunji, Laitkynsew, and Nongriat, in the present-day Meghalaya state of northeast India are examples of tree shaping. These suspension bridges are handmade from the aerial roots of living banyan fig trees, such as the rubber tree.[4] The pliable tree roots are gradually shaped to grow across a gap, weaving in sticks, stones, and other inclusions, until they take root on the other side.[4] This process can take up to fifteen years to complete.[5] There are specimens spanning over 100 feet, some can hold up to the weight of 50 people.[6][7] The useful lifespan of the bridges, once complete, is thought to be 500–600 years. They are naturally self-renewing and self-strengthening as the component roots grow thicker.[7][8]

Living trees were used to create garden houses in the Middle East, a practice which later spread to Europe. In Cobham, Kent there are accounts of a three-story house that could hold 50 people.[9]

Pleaching is a technique used in the very old horticultural practice of hedge laying. Pleaching consists of first plashing living branches and twigs and then weaving them together to promote their inosculation. It is most commonly used to train trees into raised hedges, though other shapes are easily developed. Useful implementations include fences, lattices, roofs, and walls.[3][10] Some of the outcomes of pleaching can be considered an early form of what is known today as tree shaping. In an early, labor-intensive, practical use of pleaching in medieval Europe, trees were installed in the ground in parallel hedgerow lines or quincunx patterns, then shaped by trimming to form a flat-plane grid above ground level. When the trees' branches in this grid met those of neighboring trees, they were grafted together. Once the network of joints were of substantial size, builders laid planks across the grid, upon which they built huts to live in, thus keeping the human settlement safe in times of annual flooding.[3] Wooden dancing platforms were also built and the living tree branch grid bore the weight of the platform and dancers.[11]

In late medieval European gardens through the 18th century, pleached allées, interwoven canopies of tree-lined garden avenues, were common.

Methods

There are various methods of shaping a tree.[2][12] Some of these processes are still experimental,[13]:154 whereas others are still in the research stage.[14] These methods use a variety of horticultural and arboricultural techniques to achieve an intended design. Chairs, tables, living spaces and art may be shaped from growing trees. Some techniques used are unique to a particular practice, whereas other techniques are common to all, though the implementation may be for different reasons. These methods usually start with an idea of the intended outcome. Some practitioners start with detailed drawings[15]:7 or designs.[16] Other artists start with what the tree already has.[17] :56–57 Each process has its own time frame and a different level of involvement from the tree shaper. The trees might then either remain growing, as with the living Pooktre garden chair, or perhaps be harvested as a finished work, like John Krubsack's chair.

Aeroponic culture

The oldest known living examples of woody plant shaping are the aeroponically cultured living root bridges built by the ancient War-Khasi people of the Cherrapunjee region in India. These are being maintained and further developed today by the people of that region. Aeroponic growing was first formally studied by W. Carter in 1942. Carter researched air culture growing and described "a method of growing plants in water vapor to facilitate examination of roots".[19] Later researchers, including L. J Klotz and G. G. Trowel, expanded on his work.[20] In 1957, F. W. Went described "the process of growing plants with air-suspended roots and applying a nutrient mist to the root section", and in it he coined the word 'aeroponics' to describe that process. In 2008, root researcher and craftsman Ezekiel Golan described and secured a patent for a process which allows the roots of some aeroponically grown woody plants to lengthen and thicken while still remaining flexible. At lengths of perhaps 6 metres (20 ft) or more, the soft roots can be formed into pre-determined shapes which will continue thickening after the shapes are formed and as they continue to grow.[12][21] Newer techniques and applications, such as eco-architecture, may allow architects to design, grow, and form large permanent structures, such as homes, by shaping aeroponically grown plants and their roots.[14]

Instant tree shaping

Instant tree shaping[12][22] starts with mature trees,[23] :53 perhaps 6–12 ft. (2–3.6 m) long[13]:196 and 3-4in (7.6–10 cm) in trunk diameter,[13]:172 which are bent and woven into the desired design [23] :53 and held until cast.[24][25] Understanding a tree's fluid dynamics is important to achieving the desired result.[2][17]:69

Bending is sometimes used to achieve a design.[17] If a plant's tissue is bent at too sharp an angle it may break, which can be mostly avoided by un-localizing the bend. This is achieved by making small bends along the curve of the tree. Bends are then held in place for several years until their form is permanently cast.[17]:80 The tree's rate of growth determines the time necessary to overcome its resistance to the initial bending.[13]:178 The work of bending and securing in this way might be accomplished in an hour or perhaps in an afternoon depending on the design.[22]

Ring barking is sometimes employed to help balance a design by slowing the growth of too-vigorous branches or stopping the growth of inopportunely placed branches, using different degrees of ring barking, from simple scoring to complete removal of a 3/8"-wide (1 cm) band of bark.[17]:57, 69

Creasing is folding trees such as willow and poplar over upon themselves, creating a right angle. This method is more radical than bending.[13]:80

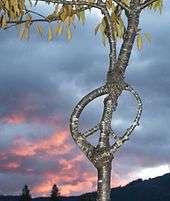

With this method it is possible to perform initial bending and grafting on a project in an hour, as with Peace in Cherry by Richard Reames,[13]:193[17]:56–57 removing supports in as little as a year and following up with minimal pruning thereafter.[26]

Gradual tree shaping

Gradual tree shaping starts with designing and framing.[22][27][28][29] These are fundamental to the success of the piece.[28][29] Once these are set up, young seedlings or saplings[15]:4 3–12 in. (7.6–30.5 cm) long[28][29] are planted.

The training starts with young seedlings, saplings or the stems of trees when they are very young,[15] :4 which are gradually shaped while the tree is growing to form the desired shape.[9] There is a small area just behind the growing tip that forms the final shape.[27][30] The shaping zone,[27][30] it is the shaping of this area requires day to day or weekly guiding of the new growth. The growth is guided along predetermined design pathways;[23] this may be a wooden jig [9] or complex wire design.[16]

With this method the time frame is longer than the other methods. A chair design might take 8 to 10 years to reach maturity[23][31] Some of Axel Erlandson trees's took as long as 40 years to assume their finished shapes.[32]

Common techniques

Framing

Framing may be used for various purposes and might consist of any one or a combination of several materials, such as timber, steel, hollowed out trees,[6] complex wire designs,[16] wooden jigs,[9] or the tree itself, living [13]:178 or dead.[33]:58 It can be used in many project designs to support grafted joints until the grafts are well-established. Some processes might employ framing to hold a shape created by bending or fletching mature trees until the tissues have overcome their resistance to the initial bending and grown enough annual rings to cast the design permanently.[13] Others might use framing to support and shape the growth of young saplings [23][30][34] until they are strong enough to maintain an intended shape without support.[30] Still other approaches might employ frames to guide the roots of aeroponically grown trees into desired shapes.

Grafting

Grafting is a commonly employed technique that exploits the natural biological process of inosculation. A branch or plant is cut and a piece of another plant is added and held in place. Various types of grafting all share the goal of encouraging the tissues of one plant to fuse with those of another.

Grafting is applied to create permanent connections and joints.[23] In some cases, trees are grafted while they are growing, [35] while in other cases, mature trees may be intertwined and the stems of two or more trees are then grafted together to create chairs, ladders, and other fanciful sculptures.[36]

Pruning

Pruning can be used to balance a design by controlling and directing growth into a desired shape.[30][33]:70 [34] Pruning above a leaf node can steer plant growth in the direction of the natural placement of that leaf bud.[13] Pruning may also be used to keep a design free of unwanted branches and to reduce canopy size.[30][34] Pruning is sometimes the only technique used to craft a project. Deciduous trees are mainly pruned in winter,[33]:137 while they are dormant above-ground, although sometimes it is necessary to prune them during the growing season. Trees repeatedly subjected to hard pruning may experience stunted growth, and some trees may not survive this treatment.

Timing

Using time as part of the construction is intrinsical to achieving this art form. [37]

Structure

Living grown structures have a number of structural mechanical advantages over those constructed of lumber and are more resistant to decay. While there are some decay organisms that can rot live wood from the outside, and though living trees can carry decayed and decaying heartwood inside them; in general, living trees decay from the inside out and dead wood decays from the outside in.[38] Living wood tissue, particularly sapwood, wields a very potent defense against decay from either direction, known as compartmentalization. This protection applies to living trees only and varies among species.

Growing structures is not as easy as it would seem.[39] Quick growing willows have been used to grow building structures, they provide support or protection.[39] A young group of German architects are in the process of such a structure and they are continually monitored and checked.[39] Once the trees are of age to be able to take on load-bearing weight they are tested for stability and strength by a structural engineer.[39] Once this is approved the supporting framework is removed.[39] Projects are limited to the trees' weight loading ability and growth.[39] This is being studied and the load capacity will be proved by testing on prototypes.[40]

Design options

Designs may include abstract, symbolic, or functional elements. Some shapes crafted and grown are purely artistic; perhaps cubes, circles, or letters of an alphabet, while other designs might yield any of a wide variety of useful shapes, such as clothes hangers,[41] laundry and wastepaper bins,[41] ladders,[42] furniture,[36] tools, and tool handles. Eye-catching structures such as living fences and jungle gyms[42] can also be grown, and even large architectural designs such as live archways, domes,[36] gazebos,[42] tunnels, and theoretically entire homes[14] are possible with careful planning, planting, and culturing over time.[11] The Human Ecology Design team (H.E.D.) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology is designing homes that can be grown from native trees in a variety of climates.[43]

Suitable trees are installed according to design specifications and then cultured over time into intended structures. Some designs may use only living, growing wood to form the structures, while others might also incorporate inclusions [22][30] such as glass, mirror, steel and stone, any of which might be used either as either structural or aesthetic elements.[30] Inclusions can be positioned in a project as it is grown and, depending on the design, may either be removed when no longer needed for support or left in place to become fixed inclusions in the growing tissue.[33]:117

Chronology of notable practitioners

War-Khasi people

The ancient War-Khasi people of India worked with the aerial roots of native banyan fig trees, adapting them to create footbridges over watercourses. Modern people of the Cherrapunjee region carry on this traditional building craft. Roots selected for bridge spans are supported and guided in darkness as they are being formed, by threading long, thin, supple banyan roots through tubes made from hollowed-out trunks of woody grasses. Preferred species for the tubes are either bamboo or areca palm, or 'kwai' in Khasi, which they cultivate for areca nuts. The Khasi incorporate aerial roots from overhanging trees to form support spans and safety handrails. Some bridges can carry fifty or more people at once. At least one example, over the Umshiang stream, is a double-decker bridge. They can take ten to fifteen years to become fully functional and are expected to last up to 600 years.[8][44]

John Krubsack

John Krubsack was an American banker and farmer from Embarrass, Wisconsin. He shaped and grafted the first known grown chair, harvesting it in 1914. He lived from 1858 to 1941. He had studied tree grafting and become a skilled found-wood furniture crafter.[45] The idea first came to him to grow his own chair during a weekend wood-hunting excursion with his son.

He started box elder seeds in 1903, selecting and planting either 28[45] or 32[46] of the saplings in a carefully designed pattern in the spring of 1907.[45] In the spring of 1908, the trees had grown to six feet tall and he began training them along a trellis, grafting the branches at critical points to form the parts of his chair.[45] In 1913, he cut all the trees except those forming the legs, which he left to grow and increase in diameter for another year, before harvesting and drying the chair in 1914; eleven years after he started the box elder seeds.[45] Dubbed The Chair that Lived; it is the only known tree shaping that John Krubsack did.[45][46] The chair is on permanent display in a Plexiglas case at the entrance of Noritage Furniture; the furniture manufacturing business now owned by Krubsack's descendants, Steve and Dennis Krubsack.[13]

Axel Erlandson

Axel Erlandson was a Swedish American farmer who started training trees as a hobby on his farm in Hilmar, California, in 1925. He was inspired by observing a natural sycamore inosculation in his hedgerow.[3] In 1945, he moved his family and the best of his trees from Hilmar to Scotts Valley, California, and in 1947,[13] opened an horticultural attraction called the Tree Circus.

Erlandson lived from 1884 to 1964; training more than 70 trees during his lifetime. He considered his methods trade secrets and when asked how he made his trees do this, he would only reply, "I talk to them."[15] His work appeared in the column of Ripley's Believe It or Not! twelve times.[47] 24 trees from his original garden have survived transplanting to their permanent home at Gilroy Gardens in Gilroy, California. His Telephone Booth Tree is on permanent display at the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland[43] and his Birch Loop tree is on permanent display at the Museum of Art and History in Santa Cruz, California. Both of these are preserved dead specimens.

Arthur Wiechula

Arthur Wiechula was a German landscape engineer who lived from 1868 to 1941. In 1926, he published Wachsende Häuser aus lebenden Bäumen entstehend (Developing Houses from Living Trees) in German.[26][48] In it, he gave detailed illustrated descriptions of houses grown from trees and described simple building techniques involving guided grafting together of live branches; including a system of v-shaped lateral cuts used to bend and curve individual trunks and branches in the direction of a design, with reaction wood soon closing the wounds to hold the curves.[49] He proposed growing wood so that it constituted walls during growth, thereby enabling the use of young wood for building.[49] Weichula never built a living home, but he grew a 394' wall of Canadian poplars to help keep the snow off of a section of train tracks.[26]

Dan Ladd

Dan Ladd is a Northampton, Massachusetts based American artist who works with trees and gourds. He began experimenting with glass, china, and metal inclusions in trees in 1977 in Vermont and started planting trees for Extreme Nature in 1978.[50] He became inspired by inosculation he noticed in nature and by the growth of tree trunks around man-made objects such as fences and idle farm equipment.[50] He shapes and grafts trees, including their fruits and their roots, into architectural and geometric forms.[50] Ladd calls human-initiated inosculation 'pleaching' and calls his own work 'tree sculpture'.[50] Ladd binds a variety of objects to trees, for live wood to grow around and be incorporated, including teacups, bicycle wheels, headstones, steel spheres, water piping, and electrical conduit.[50] He guides roots into shapes, such as stairs, using above-ground wooden and concrete forms and even shapes woody, hard-shelled Lagenaria gourds by allowing them to grow into detailed molds.[51][52] A current project at the DeCordova and Dana Museum and Sculpture Park in Lincoln, Massachusetts incorporates eleven American Liberty Elm trees grafted next to each other to form a long hillside stair banister. Another of his installations, Three Arches, consists of three pairs of 14-foot sycamore trees, which he grafted into arches to frame different city views, at Frank Curto Park in Pittsburgh.[43][53]

Nirandr Boonnetr

Nirandr Boonnetr is a Thai furniture designer and crafter. He became inspired as a child, both by a photograph of some unusually twisted coconut palms in southern Thailand and by a living fallen tree he noticed, which had grown new branches along its trunk, forming a kind of canopied bridge.[13] His hobby began in 1980 because of his concern the Thailand forests are being ravaged by woodcarvers to the point that one day the industry would eventually carve itself out of existence.[54] He began his first piece, a guava chair, around 1983.[13] Originally intended as something for his children to climb and play on, the piece evolved into a living tree chair.[13]:91 In fifteen years he created six pieces of "living furniture",[54] including five chairs and a table. The Bangkok Post dubbed him the father of Living Furniture.[13][55] Shortly thereafter, he presented a chair as a gift to her Royal Highness, Princess Sirindhorn. Nirandr Boonnetr has written a detailed, step-by-step booklet of instructions hoping his hobby of living furniture will spread to other countries.[54] One of his chairs was exhibited in the Growing Village pavilion at the World's Fair Expo 2005 in Nagakute, Aichi, Japan.

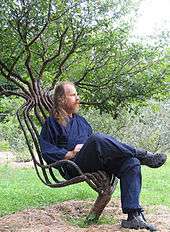

Peter Cook and Becky Northey

Peter Cook and Becky Northey are Australian artists who live in South East Queensland. Peter Cook became inspired to grow a chair in 1987, after visiting three fig trees in a remote corner of his property.[56][57] He started the next day, with 7 willow cuttings.[57] In 1988, he planted a wattle intended for harvest as a potted plant stand.[56] Becky Northey moved to Peter's property in 1995 and the two formed Pooktre.[58]

Their methods involve guiding a tree's growth along predetermined wired design pathways over a period of time.[12][31] They shape growing trees both for living outdoor art and for intentional harvest. They most often use Myrobalan Plum for shaping.[16] Examples of their functional artwork include a growing garden table, a harvested coffee table, hat stands, mirrors, and a gemstone neck piece.

Peter and Becky exhibited eight of their creations, including two people trees. in the Growing Village pavilion at the World's Fair Expo 2005 in Nagakute, Aichi Prefecture, Japan.[59] Their work was published in the annual book series, Ripley's Believe It or Not.[60]

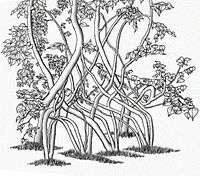

Richard Reames

Richard Reames is an American nurseryman and author based in Williams, Oregon, where he owns and manages a nursery, and design studio collectively named Arborsmith Studios.[61][62] He was inspired by the works of Axel Erlandson,[13]:150[17]:16[63] and began sculpting trees in 1991[64] or 1992.[33] He began his first experimental grown chairs [17]:57 in the spring of 1993.[17]:85

In 1995, Reames wrote and published his first book, How to Grow a Chair: The Art of Tree Trunk Topiary. In it, he coined the word arborsculpture.[17] In 2005, he published his second book, Arborsculpture: Solutions for a Small Planet.[13] He has lectured in Australia [65] and gives live demonstrations of bending and weaving a chair at garden shows, fairs and folk art festivals around America.[66]

Christopher Cattle

Christopher Cattle is a retired furniture design professor from England.[67] He started his first planting of furniture in 1996.[9] According to Cattle, he developed an idea to train and graft trees to grow into shapes, which came to him in the late 1970s,[68] in response to questions from students asking how to build furniture using less energy.[67] Using various species of trees and wooden jigs to shape them,[28] he has grown 15 three-legged stools to completion.

Cattle has multiple plantings in at least four different locations in England. He participates in woodland and craft shows in England and at the Big Tent at Falkland Palace in Scotland. He exhibited his grown stools at the World's Fair Expo 2005 in the Growing Village pavilion at Nagakute, Japan.[67]

He aims to encourage as many people as possible to grow their own furniture,[43][68] and envisions that, "One day, furniture factories could be replaced by furniture orchards."[43] Cattle calls his works grown up furniture and grown stools,[67][69] but also refers to them as grown furniture, calling them "the result of mature thinking."[67]

Mr. Wu

Mr. Wu is a Chinese pensioner who designs and crafts furniture in Shenyang, Liaoning, China.[70][71] He has patented his technique of growing wooden chairs and as of 2005, had designed, grown, and harvested one chair, in 2004, and had six more growing in his garden.[71] Wu uses young elm trees,[72] which he says are pliant and do not break easily.[71] He also says that it takes him about five years to grow a tree chair.[70]

Related practices

Other artistic horticultural practices such as bonsai, espalier, and topiary share some elements and a common heritage, though a number of distinctions may be identified.

Bonsai

Bonsai is the art of growing trees in small containers. Bonsai uses techniques such as pruning, root reduction, and shaping branches and roots to produce small trees that mimic full-sized mature trees. Bonsai is not intended for production of food, but instead mainly for contemplation by viewers, like most fine art.[73][74]

Espalier

Espalier is the art and horticultural practice of training tree branches onto ornamental shapes along a frame for aesthetic and fruit production by grafting, shaping and pruning the branches so that they grow flat, frequently in formal patterns, against a structure such as a wall, fence, or trellis.[75] The practice is commonly used to accelerate and increase production in fruit-bearing trees and also to decorate flat exterior walls while conserving space.[75]

Pleaching

Pleaching is a technique of weaving the branches of trees into a hedge commonly, deciduous trees are planted in lines, then pleached to form a flat plane on clear stems above the ground level. Branches are woven together and lightly tied.[76] Branches in close contact may grow together, due to a natural phenomenon called inosculation, a natural graft. Pleach also means weaving of thin, whippy stems of trees to form a basketry affect.[77]

Topiary

Topiary is the horticultural practice of shaping live trees, by clipping the foliage and twigs of trees and shrubs to develop and maintain clearly defined shapes,[78] often geometric or fanciful. The hedge is a simple form of topiary used to create boundaries, walls or screens. Topiary always involves regular shearing and shaping of foliage to maintain the shape.

Plantings for the future

The Fab Tree Hab

Three MIT designers – Mitchell Joachim, Lara Greden and Javier Arbona – created a concept of a living tree house which nourishes its inhabitants and merges with its environment.[79] The project of Fab Tree Hab is expected to take a minimum of five years to grow the home.[80] The plans are for the interior to be lined with clay and plastered to keep the weather outside and to look normal. The exterior is to be all natural.[80]

The Patient Gardener

A Swedish architectural firm VisionDivision took part in a week-long workshop at the Italian university Politecnico di Milano[1] with the students. The result was an 80-year plan [81] of a living cherry tree dome in an hourglass shape and grown furniture. Framing for the dome, table and a lawn chair were built. Ten Japanese cherry trees were planted in a diameter of eight-meter circle. Four of these trees are to be living staircases to a future top level. The stair trees will have their branches grafted into each other to form the rungs.[1][81] VisionDivision's architects helped the students and instructors to create an easy maintenance plan for future gardeners of the university.[81]

Baubotanik Tower

Ferdinand Ludwig designed this tower as part of his doctoral thesis with the help of Prof. Dr. Speck. "Speck become the botanical co-supervisor" said Ferdinand. Growing at the University of Stuttgart is a three-storey tower of living white willows (Salix alba). This nine-meter-tall construction is almost fully grown, with a base area of around eight square meters.[11] [40] :86

The framing is made up of mainly steel scaffolding which is supporting the growing trees, while keeping them to the correct form. They started with 400 white willow (Salix alba) grown in baskets on multiple levels with one row of willows planted into the ground. Once the trees were two meters tall, they were planted at the different levels of the tower. These plants are then trained to the design.[11][40]

The root system of the bottom level of willows needs to develop large enough to support the willows on the above levels, so that the scaffold becomes obsolete and then it and the watering and fertilising baskets can be removed altogether.[40] :86

The trees are grafted together with the objective of all the different plants eventually becoming a single organism. The overall aim is to have a living structure with the strength to support itself and to carry a working load. Ferdinand predicts the tower will be stable enough to support itself in five to ten years.[40] Ferdinand does state "However, these are only estimates."[11]

Alternative names

The practice of shaping living trees has several names. Practitioners may have their own name for their techniques, so a standard name for the various practices has not emerged.[59] Richard Reames calls the practice "arborsculpture";[64][82][83] Dan Ladd calls his work "tree sculpture";[50] Nirandr Boonnetr's work is called "living furniture";[55] Christopher Cattle calls his works "grown up furniture" and "grown stools";[67] while Peter Cook and Becky Northey call their work "Pooktre".[84][85]

The following names are also encountered:

In fiction and art

In 1516, Jean Perréal painted an allegorical image,[64] La complainte de nature à l'alchimiste errant, (The Lament of Nature to the Wandering Alchemist), in which a winged figure with arms crossed, representing nature, sits on a tree stump with a fire burning in its base, conversing with an alchemist in an ankle-length coat, standing outside of his stone-laid shoreline laboratory. Live resprouting shoots emerge from either side of the tree stump seat to form a fancifully twined and inosculated two-story-tall chair back.[92][93][94]

In 1758, Swedish scientist, philosopher, Christian mystic, and theologian Emanuel Swedenborg published Earths in the Universe, in which he wrote of visiting another planet where the residents dwelled in living groves of trees, whose growth they had planned and directed from a very young stage into living quarters and sanctuaries.[82][95]

In the late 19th century, Styrian Christian mystic and visionary Jakob Lorber published The Household of God. In it, he wrote about the wisdom of planting trees in a circle, because once grown together, the ring of trees would be a much better house than could be built.[82][96]

See also

References

- Fionnuala Fallon (3 March 2012). "The trees that shape our lives". The Irish Times. Ireland.

- Mörður Gunnarsson (2012). "Living Furniture". Cottage and Garden. Iceland. pp. 28–29.

- Mark Primack. "Pleaching". The NSW Good Wood Guide. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- Lewin, Brent (2012), "November Volume 2012 Article", India's living Bridges, Reader's Digest Australia, pp. 82–89, EAN 9311484018704, archived from the original on 6 June 2013

- Baker, Russ."",| Business Insider, 6 Oct. 2011

- "Living Growing Root Bridges Are 100% Natural Architecture". Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- "Living Root Bridge". Online Highways LLC. 21 October 2005. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- "Cherrapunjee.com: A Dream Place". Cherrapunjee Holiday Resort. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- David Davies (1 June 1996). "Plant your own furniture. Watch it grow". The Independent. UK. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- Fischbacher, Thomas (2007), Botanical Engineering (PDF), School of Engineering Sciences @ University of Southampton, archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2009

- "A very special tree house". Bio-pro.de. 4 February 2010. Retrieved 14 April 2010.

- McKee, Kate (2012), "Living sculpture", Sustainable and water wise gardens, Westview: Universal Wellbeing PTY Limited, pp. 70–73

- Richard Reames (2005), Arborsculpture: Solutions for a Small Planet, Oregon: Arborsmith Studios, ISBN 0-9647280-8-7

- "Eco-Architecture Could Produce "Grow Your Own" Homes". American Friends of Tel Aviv University.

- Erlandson, Wilma (2001), My father "talked to trees", Westview: Boulder, p. 22, ISBN 0-9708932-0-5

- Volz, Martin (October–November 2008), "A Tree shaper's life." (PDF), Queensland Smart Farmer, archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2011

- Richard Reames; Delbol, Barbara (1995), How to Grow a Chair: The Art of Tree Trunk Topiary, ISBN 0-9647280-0-1

- "Treenovations". Treenovations. Treenovations. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- Carter, W.A. (1942). A method of growing plants in water vapor to facilitate examination of roots. Phytopathology 732: 623-625.

- Stoner, R.J. (1983). Rooting in Air. Greenhouse Grower Vol I No. 11

- US "A method of shaping a portion of a woody plant into a desired form is provided. The method is effected by providing a root of a woody plant, shaping the root into the desired form and culturing the root under conditions suitable for secondary thickening of the root." 7328532, Golan, Ezekiel, "Method and a kit for shaping a portion of a woody plant into a desired form", issued 2008-02-12

- Swati Balgi (September 2009), "Live Art" (PDF), Society Interiors Magazine, Prabhadevi, Mumbai: Magna Publishing

- chaika, Chaika (2013), Growing... furniture, Bulgarian

- Rodkin, Dennis (25 February 1996), The Gardener, Chicago Tribune Sunday

- Oommen, Ansel (15 September 2013), The Artful Science of Tree Shaping, www.permaculture.co.uk

- Link, Tracey (13 June 2008), "Senior project for Bachelor of Science degree in Landscape Architecture" (PDF), Arborsculpture: An Emerging Art Form and Solutions to our Environment, p. 41, archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2012

- Roger, Fox (December 2012), "Artist tree", Better Homes and Gardens Last, p. 140

- Cattle, Christopher. "How to grow your stool". Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- "Living Trees, Living Art". Retrieved 8 May 2009.

- Peter Cook & Becky Northey (2012). Knowledge to Grow Shaped Trees. 1 (first ed.). Australia: SharBrin Publishing Ptd Ltd. ISBN 978-1-921571-54-1.

- "Artists Shape Trees into Furniture and Art" (PDF), Farm Show Magazine, vol. 32 no. 4, p. 9, June–August 2008, archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2012, retrieved 8 May 2010

- Weston, Sarah (3 October 2006), Axel Erlandson's Tree Circus, Mid-County Post

- Hicks, Ivan; Rosenfeld, Richard; Whitworth, Jo (2007), Tricks with Trees, Pavilion Books, p. 160, ISBN 978-1-86205-734-0

- "home & your garden", Going on a 'bender', Queensland Times, May 2012, p. 18

- Musitelui, Robin (30 May 1995), "Santa Cruz Sentinel Article", Architect rescue famous tree, p. 222

- Ken Mudge; Jules Janick; Steven Scofield; Eliezer E. Goldschmidt (2009), Jules Janick (ed.), A History of Grafting (PDF), Issues in New Crops and New Uses, Purdue University Center for New Crops and Plants Products, orig. pub. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. 442–443 Note large file: 8.04MB

- Zoë Hendon & Anne Massey (2019). Design, History and Time: New Temporalities in a Digital Age (first ed.). Great Britain: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 978-1-3500-6066-1.

- Jim Worrall (27 May 2007), Forest and Shade Tree Pathology: Wood Decay, archived from the original on 18 May 2011, retrieved 10 June 2011

- "BOTANY BUILDINGS Grow Buildings From Trees!". Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- Menges, Achim (2 March 2012). Material Computation 'Higher Integration in Morphogenetic Design Architectural Design (Architectural Design)'. United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-470-97330-1.

- Walpole, Lois (2004), grown home, archived from the original on 5 July 2010, retrieved 14 June 2010

- University of California, Cooperative Extension (November 2003), "Arborsculpture: Horticultural Art" (PDF), Landscape & Turf News, p. 6, archived from the original (PDF) on 10 June 2010, retrieved 12 December 2015

- Cassidy, Patti (August 2008), "A Truly Living Art", Rhode Island Home, Living and Design Magazine, Swansea, Massachusetts: Home, Living & Design, Inc., pp. 26–27

- Reddy, Jini (23 January 2010). "Trail Of The Unexpected: The root masters of India". Cherrapunjee Holiday Resort. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- Mack, Daniel (31 December 1996), Making Rustic Furniture: The Tradition, Spirit, and Technique with Dozens of Project Ideas (illustrated ed.), Lark Books, p. 160, ISBN 1-887374-12-4

- "Only Natural Grown Chair". Shawano Leader Newspaper. Wisconsin Historical Society. 19 October 1922. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- "Obituary of Axel Erlandson", Turlock Journal, p. 15, 30 April 1964

- Wiechula, Arthur (1926) [1926], Wachsende Häuser aus lebenden Bäumen entstehend (Developing Houses from Living Trees), Verl. Naturbau-Ges, p. 320

- "designboom:history of arborsculpture".

- Ladd, Dan (22 January 2009), Sculpturefest 2008: Daniel Ladd, archived from the original on 27 July 2011, retrieved 14 June 2010

- "Dan Ladd's home page". Dan Ladd. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- Extreme Nature: The Sculptures of Dan Ladd at Putney Library Archived 24 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine 10 October 2006.

- Shaw, Kurt (11 August 2002), "Persephone Project promotes gardening as contemporary art medium", TribLiveNews, archived from the original on 15 June 2015, retrieved 30 June 2010

- Steve, Rhodes (6 April 2003), "No need to pull up a stump: Short of garden furniture?", Sunday Mail

- "The father of Living Furniture", Bangkok Post, 16 January 1996

- "Pooktre". Northey, Becky. Retrieved 5 May 2010. (Archived by WebCite at "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 2010-05-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link))

- "Pooktre", Bricks & Mortar Magazine, 2008

- "Pooktre". Northey, Becky. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- McKie, Fred (20 April 2005), "Warwick artist grows wooden 'jewels' for World Expo", The Southern Free Times

- Tibballs, Geoff; Proud, James (2009), Ripley's Believe It or Not: Seeing is Believing, Orlando, FL: Ripley Publishing Ltd, p. 32, ISBN 978-1-893951-45-7

- Biography of Richard Reames, archived from the original on 31 December 2010, retrieved 27 June 2010

- Company profile: Arborsmith Studios, archived from the original on 22 September 2010

- S. Okenga (2001), Eden on Their Minds: American Gardeners with Bold Visions, Clarkson Potter, p. 110, ISBN 0-609-60587-9

- Nestor, James (February 2007), "Branching Out", Dwell, Dwell, LLC, p. 96, retrieved 15 June 2010

- Arbor Sculpture: "If you like I'll grow you a mirror" (PDF), The Cutting Edge; the Newsletter of the Victorian Woodworkers Association, Inc., June 2006, p. 16, archived from the original (PDF) on 25 October 2009, retrieved 15 May 2010

- Life and Limbs, archived from the original on 18 August 2011, retrieved 10 November 2011

- Cattle, Christopher. "grown furniture home page". Christopher Cattle. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- "Grown Furniture at the Museum of English Rural Life" (Press release). University of Reading, UK. 26 March 2008. Archived from the original on 23 December 2012. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- Cattle, Christopher. "grown furniture examples". Christopher Cattle. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- "Five year deliveries", China Morning Business View, Farmington, Michigan: AccessMyLibrary, via CMP Information Ltd., via The Gale Group, 2003, retrieved 15 June 2010

- Treet Them Well, Chaotic Web Development, via ananova.com), 2 February 2005, retrieved 15 June 2010

- Hoffman, Bill; Wire Services (3 February 2005), "Weird But True", New York Post (news ed.), p. 23, retrieved 15 June 2010

- Chan, Peter (1987), Bonsai Masterclass, Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., ISBN 0-8069-6763-3

- Koreshoff, Deborah R. (1984), Bonsai: Its Art, Science, History and Philosophy, Timber Press, Inc., p. 1, ISBN 0-88192-389-3

- Evans, Erv, Espalier, North Carolina State University Horticultural Science Department Cooperative Extension Service, archived from the original on 8 July 2010, retrieved 29 June 2010

- The Complete Guide to Pruning and Training Plants, Joyce and Brickell, 1992, page 106, Simon and Schuster

- John Seymour (1984). The Forgotten Arts A practical guide to traditional skills. Angus & Robertson Publishers. p. 54. ISBN 0-207-15007-9.

- Coombs, Duncan; Blackburne-Maze, Peter; Cracknell, Martyn; Bentley, Roger (2001), "9", The Complete Book of Pruning (illustrated ed.), Sterling Publishing Company, p. 224, ISBN 978-1-84188-143-0

- "A LIVING HOUSE - Terreform's Fab Tree Hab". Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- "Grow your own home: 'Fab tree hab'". Archived from the original on 15 January 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- Karen Cilento (28 October 2011), "The Patient Gardener / Visiondivision", Arch Daily, Plataforma Networks, retrieved 8 March 2012

- Foer, Joshua; Reames, Richard (Winter 2005–2006), "How to Grow a Chair: An Interview with Richard Reames", Cabinet Magazine, retrieved 15 May 2010.

- Jules Janick (2009), Horticultural Reviews, 35, John Wiley and Sons, p. 443, ISBN 978-0-470-38642-2

- Jaya Jiwatram (25 August 2008), "We're going to Live in the Trees", Popular Science Magazine, retrieved 10 June 2011

- Hao Jinyao (11 May 2009), "The art of Tree shaping", Culture

- Marras, Amerigo (1 February 1999), ECO-TEC: Architecture of the In-Between, Princeton Architectural Press, ISBN 978-1-56898-159-8

- Stephen Lesiuk. "BIOTECTURE II: PLANTBUILDING INTERACTION". Dept of Architecture, Sydney University. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

- "Living Art". Discoveries. 6 September 2011. Archived from the original on 5 December 2010.

- Varkulevicius, Jane (2010), Pruning for Flowers and Fruit, CSIRO Publishing, p. 96

- Bunny Guinness (18 September 2011), "Train your trees into extraordinary shapes", Sunday Telegraph, UK/

- Oommen, Ansel. “Baubotanik: The Botanically Inspired Design System That Creates Living Buildings.” ArchDaily, ArchDaily, 23 Oct. 2015, www.archdaily.com/775884/baubotanik-the-botanically-inspired-design-system-that-creates-living-buildings

- "designboom: the alchemic force of the imagination transmutes nature". Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- Perréal, Jean (1516). "l'Alchimie". Musée Marmottan Monet. Archived from the original on 19 March 2009. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- Kamil, Neil (2005), Fortress of the Soul: Violence, Metaphysics, and Material Life in the Huguenots' New World 1517–1751, JHU Press, pp. 384–385, ISBN 0-8018-7390-8, retrieved 22 February 2010

- Swedenborg, Emanuel (2008) [1758], Earths in the Universe, BiblioBazaar, LLC, p. 104, ISBN 978-1-4375-3106-0

- Lorber, Jakob (1995), Die Haushaltung Gottes (The Household of God) (Translation by Violet Ozols ed.), Lorber Verlag, p. 564, ISBN 978-3-87495-314-6

External links

- "The Art of Tree Shaping", by Becky Northey, Permaculture, 30th January 2014. [Retrieved 19 April 2019].

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tree shaping. |