Lapidary

A lapidary (lapidarist, Latin: lapidarius) is an artist or artisan who forms stone, minerals, or gemstones into decorative items such as cabochons, engraved gems (including cameos), and faceted designs. A lapidarist uses the lapidary techniques of cutting, grinding, and polishing.[1][2][3] Hardstone carving requires specialized carving techniques.[2]

Diamond cutters are generally not referred to as lapidaries, due to the specialized techniques which are required to work diamonds. In modern contexts, a gemcutter is a person who specializes in cutting diamonds, but in older historical contexts it refers to artists producing engraved gems such as jade carvings. By extension, the term lapidary has sometimes been applied to collectors of and dealers in gems, or to anyone who is knowledgeable in precious stones.[4]

Etymology

The etymological roots of the word lapidary is the Latin word lapis, which means stone.[5] In the 14th century, the term evolved from lapidarius, meaning "stonecutter" or "working with stone", into the Old French word lapidaire, meaning "one skilled in working with precious stones".[5]

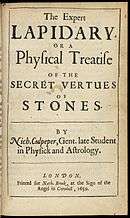

In French, and later English, the term is also used for a treatise on precious stones that details their appearance, formation, and properties—particularly in terms of the "stones' powers"—as believed in medieval Europe. The beliefs about the powers of stones included their ability to prevent harm, heal ailments, or offer health benefits.[6] Lapidary appeared as an English adjective in the 18th century.[5]

History

The earliest known lapidary work likely occurred during the Stone Age.[1][7] As people created tools from stone, they inevitably realized that some geological materials were harder than others. The next earliest documented examples of what one may consider being lapidary arts came in the form of drilling stone and rock. The earliest roots of drilling rocks date back to approximately one million years ago.[8]

The early Egyptians developed cutting and jewelry fashioning methods for lapis lazuli, turquoise, and amethyst.[9]

The lapidary arts were quite well-developed in the Indian subcontinent by early-1st millennium CE. The surviving manuscripts of the 3rd-century Buddhist text Rathanpariksha by Buddha Bhatta, and several Hindu texts of mid-1st millennium CE such as Agni Purana and Agastimata, are Sanskrit treatises on lapidary arts. They discuss sources of gems and diamonds, their origins, qualities, testing, cutting and polishing, and making jewelry from them.[10][11][12] Several other Sanskrit texts on gems and lapidary arts have been dated to post-10th century, suggesting a continuous lapidary practice.[13]

According to Jason Hawkes and Stephanie Wynne-Jones, archaeological evidence suggests that trade in lapidary products between Africa and India was established in the 1st millennium CE. People of the Deccan region of India and those near the coast of East Africa had innovated their own techniques for lapidary before the 10th century, as evidenced by excavations and Indian and non-Indian texts dated to that period.[14]

Lapidary was also a significant tradition in early Mesoamerica. The lapidary products were used as status symbols, for offerings, and during burials. They were made from shell, jade, turquoise, and greenstones. Aztec lapidaries used string saws and drills made of reed and bone as their lapidary tools.[15]

Techniques

There are three broad categories of lapidary arts: tumbling, cabochon cutting, and faceting.

Most modern lapidary work is done using motorized equipment. Polishing is done with resin- or metal-bonded emery, silicon carbide (carborundum), aluminium oxide (corundum), or diamond dust in successively decreasing particle sizes until a polish is achieved. In older systems, the grinding and polishing powders were applied separately to the grinding or buffing wheel. Often, the final polish will use a different medium such as tin oxide or cerium(IV) oxide. Cutting of harder stones is done with a diamond-edged saw. For softer materials, a medium other than diamonds can be used, such as silicon carbide, garnet, emery, or corundum. Diamond cutting requires the use of diamond tools because of the extreme hardness of diamonds. The cutting, grinding, and polishing operations are usually lubricated with water, oil, or other liquids. Beyond these broader categories, there are other specialized forms of lapidary techniques, such as casting, carving, jewelry, and mosaics.

Another specialized form of lapidary work is the inlaying of marble and gemstones into a marble matrix. This technique is known in English as pietra dura, for the hardstones that are used, like onyx, Jasper and carnelian. In Florence and Naples, where the technique was developed in the 16th century, it is called opere di commessi. The Medici Chapel at San Lorenzo in Florence is completely veneered with inlaid hard stones. The specialty of micromosaics, which developed in the late-18th century in Naples and Rome, is sometimes covered under the umbrella term of lapidary work. In this technique, minute slivers of glass are assembled to create still life, cityscape views, and other images. In China, lapidary work specializing in jade carving has been continuous since at least the Shang dynasty.

Societies and Clubs

There are lapidary clubs throughout the world. In Australia, there are numerous gem shows, including an annual gem show called the GYMBOREE, which is a nationwide lapidary competition. There is a collection of gem and mineral shows held in Tucson, Arizona, at the beginning of February each year. The event began with the Tucson Gem and Mineral Society Show and has now grown to include dozens of other independent shows. In 2012, this concurrent group of shows constituted the largest gem and mineral event in the world.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lapidarists. |

References

- Ripley, George; Dana, Charles A., eds. (1860). "Lapidary". The New American Cyclopædia. Volume X, Jerusalem–MacFerrin. New York: Appleton. pp. 310–311.

- Kraus, Pansy D. (1987). "Preface". Introduction To Lapidary. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. p. ix. ISBN 978-0-8019-7266-9.

- "Oxford Dictionaries: Definition of lapidary in English". Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 22 September 2012.

- "lapidary". Webster's New World College Dictionary, 4th Ed. Archived from the original on 3 May 2007.

- Douglas Harper (2014), Lapidary, Online Etymology Dictionary

- William W. Kibler (1995). Medieval France: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 990–991. ISBN 978-0-8240-4444-2.

- Cocca, Enzo; Mutri, Guiseppina (2013). "The lithic assemblages: production, use and discard". In Garcea, Elena A. A. (ed.). Gobero: The No-Return Frontier Archaeology and Landscape at the Sahara-Sahelian Borderland. Journal of African Archaeology Monograph Series 9. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Africa Magna Verlag. pp. 129–166. ISBN 978-3-937248-34-9.

- The full and complete history of the lapidary arts International Gem Society, Retrieved January 7, 2015,

- Kraus, Pansy D. (1987). "History of Lapidary". Introduction To Lapidary. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-8019-7266-9.

- Sures Chandra Banerji (1989). A Companion to Sanskrit Literature. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 121. ISBN 978-81-208-0063-2.

- Mohsen Manutchehr-Danai (2009). Dictionary of Gems and Gemology. Berlin: Springer. p. 10. ISBN 978-3-540-72795-8.

- Louis Finot (1896). Les lapidaires indiens (in Sanskrit and French). Champion. pp. 77–139, see other chapters as well.

- Louis Finot (1896). Les lapidaires indiens (in Sanskrit and French). Champion. pp. xiv–xv with footnotes.

- Jason D. Hawkes and Stephanie Wynne-Jones (2015), India in Africa: Trade goods and connections of the late first millennium, L’Afrique Orientale et l’océan Indien: connexions, réseaux d'échanges et globalization, Journal: Afriques, Volume 6 (June 2015), Quote: " The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, and the Sanskrit Mricchakatika both refer to the jewels made in Ujjain. The evidence from excavations at Ujjain itself, as well as that from surrounding villages, supports this identification. These workshops fed the main market for international trade at the city port of Baruch, at the mouth of the Narmada, which has long been recognized as the main coastal port of the early first millennium. At some point in the mid to late first millennium AD, the center of lapidary workshops appears to have moved from Ujjain to Limudra, and the main port shifted to Khambhat. Exactly when this shift took place and why it occurred is unclear. What is interesting, however, is that throughout the first millennium AD there was a clear and close spatial association between 1) source areas, 2) production centers, and 3) ports connected to the Indian Ocean."

- Susan Toby Evans; David L. Webster (2013). Archaeology of Ancient Mexico and Central America: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 400. ISBN 978-1-136-80185-3.