First Babylonian dynasty

The First Babylonian Empire, or Old Babylonian Empire, is dated to c. 1894 BC – c. 1595 BC, and comes after the end of Sumerian power with the destruction of the 3rd dynasty of Ur, and the subsequent Isin-Larsa period. The chronology of the first dynasty of Babylonia is debated as there is a Babylonian King List A[1] and a Babylonian King List B.[2] In this chronology, the regnal years of List A are used due to their wide usage. The reigns in List B are longer, in general.

First Babylonian Empire | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1894 BC – c. 1595 BC | |||||||||

| Capital | Babylon | ||||||||

| Common languages | Babylonian language | ||||||||

| Religion | Babylonian religion | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

• c. 1894–1881 BC | Sumu-abum (first) | ||||||||

• c. 1626–1595 BC | Samsu-Ditana (last) | ||||||||

| Historical era | Bronze Age | ||||||||

• Established | c. 1894 BC | ||||||||

• Sack of Babylon | c. 1595 BC | ||||||||

• Disestablished | c. 1595 BC | ||||||||

| |||||||||

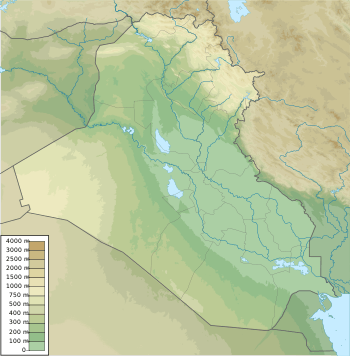

| Today part of | Iraq | ||||||||

Before the First Dynasty

The more eminent time period preceding the First Dynasty, but taking place after the reign of Sargon the Great (the first ruler of the Akkadian Empire, c. 2334–2284 BC), is referred to as the Third Dynasty of Ur or the Ur III period. This time period took place during the end of the third millennium BC and early second millennium BC. Common behaviors of the kings during this time period, especially Ur-Namma and Shulgi, included reunifying Mesopotamia and developing rules for the kingdom to abide by. Most notably, these rulers of Ur contributed to the development of ziggurats, which were religious monumental stepped towers that would in turn bring religious peoples together. In order to gain and retain power, it was not unfamiliar for Ur princesses to marry the kings of Elam; Elaminites were a commonly known enemy of Mesopotamians.[3] Ur rulers would also, along with arranged marriage, send gifts and letters to other rulers as a peace offering. This is known because of the hefty amount of administrative records dating to the Ur III period, which can now be found on display through collections and museums.[4]

First Dynasty: middle chronology

The middle chronology is:

| King | Reigned | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sumu-abum or Su-abu | c. 1894–1881 BC | Contemporary of Ilushuma of Assyria | |

| Sumu-la-El | c. 1881–1845 BC | Contemporary of Erishum I of Assyria | |

| Sabium or Sabum | c. 1845–1831 BC | Son of Sumu-la-El | |

| Apil-Sin | c. 1831–1813 BC | Son of Sabium | |

| Sin-muballit | c. 1813–1792 BC | Son of Apil-Sin | |

| Hammurabi (First major ruler)[5] | c. 1792–1750 BC | Contemporary of Zimri-Lim of Mari, Siwe-palar-huppak of Elam and Shamshi-Adad I | |

| Samsu-iluna | c. 1750–1712 BC | Son of Hammurabi | |

| Abi-eshuh or Abieshu | c. 1712–1684 BC | Son of Samsu-iluna | |

| Ammi-ditana | c. 1684–1647 BC | Son of Abi-eshuh | |

| Ammi-saduqa or Ammisaduqa | c. 1647–1626 BC | Venus tablet of Ammisaduqa | |

| Samsu-Ditana | c. 1626–1595 BC | Sack of Babylon by the Hittites. | |

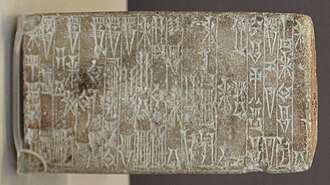

Origins of the First Dynasty

The actual origins of the First Babylonian dynasty are rather hard to pinpoint with great certainty simply because Babylon itself, due to a high water table, yields very few archaeological materials intact. Thus, the evidence that survived throughout the years includes written records such as royal and votive inscriptions, literary texts, and lists of year-names. The minimal amount of evidence in economic and legal documents makes it difficult to illustrate the economic and social history of the First Babylonian Dynasty, but with historical events portrayed in literature and the existence of year-name lists, it is possible to establish a chronology.[6]

The first kings of the dynasty

With little evidence there is not much known about the reigns of the kings from Sumuabum through Sin-muballit other than the fact they were Amorites rather than indigenous Akkadians. What is known, however, is that they accumulated little land. When the Amorite king, Hammurabi came into power his military victories were successful in gaining land for the Empire. However, Babylon was just one of the several important powers among Assyria ruled by Shamshi-Adad I and Larsa ruled by Rim-Sin I.

The accomplishments of the first known king of the Dynasty, Sumuabum, include his efforts in expanding the Babylonian territory when conquering Dilbat and Kish.[10] His successor, Simualailum, was able to complete the wall around Babylon that Sumuabum had begun constructing. Sumualialum was also able to defeat rebellions in Kish and became successful in the destruction of Kazallu while possessing brief control over Nippur (though it did not last).[11] There is little to know about the reigns of Sabium, Apil-Sin and Sinmuballit other than that they continued ruling the conquered territory as well as strengthened the walls and began building canals. However, Sinmuballit is known for his successful defeats over Rim-Sim which protected Babylon from further invasion.[12] Sinmuballit would then pass on his role as king to his son, Hammurabi.

King Hammurabi

Hammurabi is also at times referred to as "Hammurapi" in ancient texts, including multiple primary source Babylonian letters. This is mainly due to the common variants of an Amorite name, just as "Dipilirabi" is also known as "Dipilirapi".[14]

One of the most famous ancient near eastern texts, let alone artifactual text from The First Babylonian Dynasty is the “Code of Hammurapi”. The code is written in cuneiform on a 7 foot tall diorite stele that portrays the Babylonian King receiving his kingship from the Sun God, Shamash, on the top of the stele with a collection of written laws at the bottom. The text itself explains how Hammurabi came into power and created a set of laws to ensure justice throughout his territory, the divine role that was given to him. Before presenting the laws written in the Code, Hammurabi states "When the god Marduk commanded me to provide just ways for the people of the land (in order to attain) appropriate behavior, I established truth and justice as the declaration of the land, I enhanced the well-being of the people" and goes on to display the laws of just punishment for crimes and provides rules for his people to abide by.[15] King Hammurabi ruled Babylon from 1792 to 1750 BCE and his code will be noted as one of the oldest living written laws in history.

When Hammurabi first came into power the empire only consisted of a few towns in the surrounding area: Dilbat, Sippar, Kish, and Borsippa. By 1761, Hammurabi managed to succeed in capturing the formidable power of Eshnunna, inheriting its well-established commercial trade routes and the economic stability that came along with it. It was not long before Hammurabi's army took Assyria and parts of the Zagros Mountains. Eventually in 1760, Babylon gained control over Mari, making up virtually all the territory of Mesopotamia under the Third Dynasty of Ur. During Hammurabi's thirtieth year as king, he conquered Larsa from Rim-Sin I, thus, gaining control over the lucrative urban centers of Nippur, Ur, Uruk, and Isin. Hammurabi was one of the most notable Kings during the First Babylonian Dynasty because of his success in gaining control over Southern Mesopotamia and establishing Babylon as the center of his Empire. Babylon would then come to dominate Mesopotamia for over a thousand years.[16]

Zimri-lim plays a significant role for the historians of today by which this figure contributed immense amounts of historical documents that help to understand the history of Hammurabi and the diplomacy of The First Babylonian Dynasty during his reign. The archives of Hammurabi at the site of Babylon cannot be recovered due to its remains lying under a water table, practically resulting to mud.[17] Zimri-Lim's palace in Mari held an archive, known as Ebla, which included letters and other texts that provide insight into the alliance between the king and Hammurabi, as well as other leaders in the Syrian and Mesopotamian region. These documents survived because of Hammurabi who had burned the palace down thus burying the material and preserving it.[18] War was a common aspect for the Kingdoms of Syria and Mesopotamia so inevitably majority of the documents were in regard to military affairs. The documents included letters written by the messengers of the kings, they would discuss conflicts, divine oaths, agreements and treaties between the powers.[19]

Hammurabi's Successors

There is also little information to know about the kings who succeeded Hammurabi. The reigns of kings from Samsuiluna to Samsuditana have very few records to note the history of what went on during their time as rulers. However, we do know that Samsuiluna was successful in beating Rim-Sim II but lost major parts of conquered land, only really ruling the main territory that remained after Hammurabi's reign. The kings who succeeded him would face similar turmoil.[20] The first Babylonian Dynasty eventually came to an end as the Empire lost territory, money and faced great degradation. The attacks from Hittites who were trying to expand outside of Anatolia eventually came to the destruction of Babylon. The Kassite Period then followed the First Babylonian Dynasty ruling from 1570-1154 BCE.[21]

Solar aspects in Babylon

Solar aspects played a certain role in the Royal Power of Old Babylonia. Shamash is the god of the sun as well as the god of justice and divination as mentioned in The Code of Hammurapi the text states "May the god Shamash, the great judge of heaven and earth, who provides just ways for all living creatures, the lord, my trust, overturn his kingship".[22] Shamash was considered to have an influence on Hammurabi and fosters the idea that he will execute the laws of justice on land as Shamash does in with his role as a god.[23]

A recent translation of the Chogha Gavaneh tablets which date back to 1800 BC indicates there were close contacts between this town located in the intermontane valley of Islamabad in Central Zagros and Dyala region.

A text about the fall of Babylon by the Hittites of Mursilis I at the end of Samsuditana's reign, tells a story about a twin eclipse which is crucial for there to be a correct Babylonian chronology. The pair of lunar and solar eclipses occurred in the month of Shimanu (Sivan). The lunar eclipse took place on February 9, 1659 BC. It started at 4:43 and ended at 6:47. The latter was invisible which satisfies the record and which also tells that the moon setting was still eclipsed. The solar eclipse occurred on February 23, 1659. It started at 10:26, has its maximum at 11:45, and ended at 13:04.[24] The Venus tablets of Ammisaduqa (i.e., several ancient versions on clay tablets) are famous, and several books had been published about them. Several dates have been offered but the old dates of many sourcebooks seem to be outdated and incorrect. There are further difficulties: the 21-year span of the detailed observations of the planet Venus may or may not coincide with the reign of this king, because his name is not mentioned, only the Year of the Golden Throne. A few sources, some printed almost a century ago, claim that the original text mentions an occultation of Venus by the moon. However, this may be a misinterpretation.[25] Calculations support 1659 for the fall of Babylon, based on the statistical probability of dating based on the planet's observations. The presently accepted middle chronology is too low from the astronomical point of view.[26]

Seals

Devotion scene

Devotion scene Hero fighting two winged demons

Hero fighting two winged demons Presentation to a divinity

Presentation to a divinity Scene of devotion with inscription

Scene of devotion with inscription

See also

- Chronology of the Ancient Near East

- Kings of Babylon

- List of lists of ancient kings

- List of Mesopotamian dynasties

- Short chronology timeline

- Timeline of the Assyrian Empire

References

- BM 33332.

- BM 38122.

- Stolper, Matthew W. (1984). Elam: Surveys of Political History and Archaeology.

- Podany, Amanda H. (2010). Brotherhood of Kings. p. 62.

- Frankfort, Henri; Roaf, Michael; Matthews, Donald (1996). The Art and Architecture of the Ancient Orient. Yale University Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-300-06470-4.

- Seri, Andrea (2012). Local Power of Old Babylonian Mesopotamia. pp. 12–13.

- Cuneiform Tablets in the British Museum (PDF). British Museum. 1905. pp. Plates 44 and 45.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (Ernest Alfred Wallis); King, L. W. (Leonard William) (1908). A guide to the Babylonian and Assyrian antiquities. London : Printed by the order of the Trustees. p. 147.

- For full transcription: "CDLI-Archival View". cdli.ucla.edu.

- King, Leonard William (1969). A History of Babylon.

- King, Leonard William (1969). A History of Babylon.

- King, Leonard William (1969). A History of Babylon.

- Roux, Georges, "The Time of Confusion", Ancient Iraq, Penguin Books, p. 266, ISBN 9780141938257

- Luckenbill, D.D (1984). The Name Hammurabi. p. 253.

- Coogan, Micheal D. Ancient Near Eastern Texts. Oxford University Press. pp. 87–90.

- Podany, Amanda H. (2010). Brotherhood of Kings. p. 65.

- Klengel-brandt, Evelyn. Bbaylon.

- Podany, Amanda H. Brotherhood of Kings. p. 70.

- Podany, Amanda H. (2010). Brotherhood of kings. p. 72.

- Moorey, P.R.S (1978). Ancient Near Eastern Cylinder Seals.

- Coogan, Micheal D. Ancient Near Eastern Texts. Oxford University Press. pp. 87–90.

- The Code of Hammurapi.

- Charpin, Dominique. ""I am the Sun of Babylon"; Solar Aspects of Royal Power in Old Babylonian Mesopotamia". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Huber, Peter (1982). "Astronomical dating of Babylon I and Ur III". Monographic Journals of the Near East: 41.

- Reiner, Erica; D. Pingree. Babylonian Planetary Omens The Venus, the Tablet of Ammisaduqa.

- Kelley, David H.; E. F. Milone; Anthony F. Aveni (2004). Exploring Ancient Skies: An Encyclopedic Survey of Archaeoastronomy. New York: Springer. ISBN 0-387-95310-8.