Tapestry

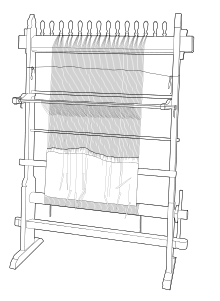

Tapestry is a form of textile art, traditionally woven by hand on a loom. Tapestry is weft-faced weaving, in which all the warp threads are hidden in the completed work, unlike cloth weaving where both the warp and the weft threads may be visible. In tapestry weaving, weft yarns are typically discontinuous; the artisan interlaces each coloured weft back and forth in its own small pattern area. It is a plain weft-faced weave having weft threads of different colors worked over portions of the warp to form the design.[1][2]

Most weavers use a natural warp thread, such as wool, linen or cotton. The weft threads are usually wool or cotton but may include silk, gold, silver, or other alternatives.

Etymology

First attested in English in 1467, the word tapestry derives from Old French tapisserie, from tapisser,[3] meaning "to cover with heavy fabric, to carpet", in turn from tapis, "heavy fabric", via Latin tapes (gen: tapetis),[4] which is the Latinisation of the Greek τάπης (tapēs; gen: τάπητος, tapētos), "carpet, rug".[5] The earliest attested form of the word is the Mycenaean Greek 𐀲𐀟𐀊, ta-pe-ja, written in the Linear B syllabary.[6]

Function

The success of decorative tapestry can be partially explained by its portability (Le Corbusier once called tapestries "nomadic murals").[7] Kings and noblemen could roll up and transport tapestries from one residence to another. In churches, they were displayed on special occasions. Tapestries were also draped on the walls of castles for insulation during winter, as well as for decorative display.

In the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, a rich tapestry panel woven with symbolic emblems, mottoes, or coats of arms called a baldachin, canopy of state or cloth of state was hung behind and over a throne as a symbol of authority.[8] The seat under such a canopy of state would normally be raised on a dais.

The iconography of most Western tapestries goes back to written sources, the Bible and Ovid's Metamorphoses being two popular choices. Apart from the religious and mythological images, hunting scenes are the subject of many tapestries produced for indoor decoration.

Historical development

Tapestries have been used since at least Hellenistic times. Samples of Greek tapestry have been found preserved in the desert of Tarim Basin dating from the 3rd century BC.

The form reached a new stage in Europe in the early 14th century AD. The first wave of production occurred in Germany and Switzerland. Over time, the craft expanded to France and the Netherlands. The basic tools have remained much the same.

In the 14th and 15th centuries, Arras, France was a thriving textile town. The industry specialised in fine wool tapestries which were sold to decorate palaces and castles all over Europe. Few of these tapestries survived the French Revolution as hundreds were burnt to recover the gold thread that was often woven into them. "Arras" is still used to refer to a rich tapestry no matter where it was woven. Indeed, as literary scholar Rebecca Olson argues, Arras were the most valuable objects in England during the early modern period and inspired writers such as William Shakespeare and Edmund Spenser to weave these tapestries into their most important works such as Hamlet and The Faerie Queene.[9]

By the 16th century, Flanders, the towns of Oudenaarde, Brussels, Geraardsbergen and Enghien had become the centres of European tapestry production. In the 17th century, Flemish tapestries were arguably the most important productions, with many specimens of this era still extant, demonstrating the intricate detail of pattern and colour embodied in painterly compositions, often of monumental scale.

In the 19th century, William Morris resurrected the art of tapestry-making in the medieval style at Merton Abbey. Morris & Co. made successful series of tapestries for home and ecclesiastical uses, with figures based on cartoons by Edward Burne-Jones.

Kilims and Navajo rugs are also types of tapestry work.

In the mid-twentieth century, new tapestry art forms were developed by children at the Ramses Wissa Wassef Art Centre in Harrania, Egypt, and by modern French artists under Jean Lurçat in Aubusson, France. Traditional tapestries are still made at the factory of Gobelins and a few other old European workshops, which also repair and restore old tapestries.

Contemporary tapestry

While tapestries have been created for many centuries and in every continent in the world, what distinguishes the contemporary field from its pre-World War II history is the predominance of the artist as weaver in the contemporary medium.

This trend has its roots in France during the 1950s, where one of the "cartoonists" for the Aubusson tapestry studios, Jean Lurçat spearheaded a revival of the medium by streamlining color selection, thereby simplifying production,[10] and by organizing a series of Biennial exhibits held in Lausanne, Switzerland. The Polish work submitted to the first Biennale, which opened in 1962, was quite novel.[11] Traditional workshops in Poland had collapsed as a result of the war. Also art supplies in general were hard to acquire. Many Polish artists had learned to weave as part of their art school training and began creating highly individualistic work by using atypical materials like jute and sisal.[11] With each Biennale the popularity of works focusing on exploring innovative constructions from a wide variety of fiber resounded around the world.[12]

There were many weavers in pre-war United States, but there had never been a prolonged system of workshops for producing tapestries. Therefore, weavers in America were primarily self-taught and chose to design as well as weave their art. Through these Lausanne exhibitions, US artists/weavers, and others in countries all over the world, were excited about the Polish trend towards experimental forms.[11] Throughout the 1970s almost all weavers had explored some manner of techniques and materials in vogue at the time. What this movement contributed to the newly realized field of art weaving, termed "contemporary tapestry", was the option for working with texture, with a variety of materials and with the freedom for individuality in design

In the 1980s it became clear that the process of weaving weft-faced tapestry had another benefit, that of stability. The artists who chose tapestry as their medium developed a broad range of personal expression, styles and subject matter, stimulated and nourished by an international movement to revive and renew tapestry traditions from all over the world. Competing for commissions and expanding exhibition venues were essential factors in how artists defined and accomplished their goals.

Much of the impetus in the 1980s for working in this more traditional process came from the Bay Area in Northern California where, twenty years earlier, Mark Adams, an eclectic artist, had two exhibits of his tapestry designs. He went on to design many large tapestries for local buildings. Hal Painter, another well-respected artist in the area became a prolific tapestry artist during the decade weaving his own designs. He was one of the main artists to "…create the atmosphere which helped give birth to the second phase of the contemporary textile movement – textiles as art – that recognition that textiles no longer had to be utilitarian, functional, to serve as interior decoration."[13]

Early in the 1980s many artists committed to getting more professional and often that meant traveling to attend the rare educational programs offered by newly formed ateliers, such as the San Francisco Tapestry Workshop, or to far-away institutions they identified as fitting their needs. This phenomenon was happening in Europe and Australia as well as in North America.

Opportunities for entering juried tapestry exhibits were beginning to happen by 1986, primarily because the American Tapestry Alliance (ATA), founded in 1982, organised biennial juried exhibits starting in 1986. The biennials were planned to coincide with the Handweavers Guild or America's "Convergence" conferences. The new potential for seeing the work of other tapestry artists and the ability to observe how one's own work might fare in such venues profoundly increased the awareness of a community of like-minded artists. Regional groups were formed for producing exhibits and sharing information.[14]

The desire of many artists for greater interaction escalated as an international tapestry symposium in Melbourne, Australia in 1988 lead to a second organization committed to tapestry, the International Tapestry Network (ITNET). Its goal was to connect American tapestry artists with the burgeoning international community. The magazines were discontinued in 1997 as communicating digitally became a more useful tool for interactions. As the world has moved into the digital age, tapestry artists around the world continue to share and inspire each other's work.

By the new millennium however, fault lines had surfaced within the field. Many universities that previously had strong weaving components in their art departments, such as San Francisco State University, no longer offered handweaving as an option as they shifted their focus to computerized equipment. A primary cause for discarding the practice was the fact that only one student could use the equipment for the duration of a project whereas in most media, like painting or ceramics, the easels or potters wheels were used by several students in a day. Worldwide, people from all different cultures began adopting these forms of decor for profession and personal use.[15]

At the same time, "fiber art" had become one of the most popular mediums in their art programs. Young artists were interested in exploring a wider scope of processes for creating art through the materials classified as fiber. This shift to more multimedia and sculptural forms and the desire to produce work more quickly had the effect of pushing contemporary tapestry artists inside and outside the academic institutions to ponder how they might keep pace in order to sustain visibility in their art form.[16]

Susan Iverson, a professor in the School of the Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University, explains her reasons:

I came to tapestry after several years of exploring complex weaves. I became enamored with tapestry because of its simplicity — its straightforward qualities. It allowed me to investigate form or image or texture, and it had the structural integrity to hold its own form. I loved the substantial quality of a tapestry woven with heavy threads—its object quality.[17]

Another prominent artist, Joan Baxter, states:

My passion for tapestry arrived suddenly on the first day of my introduction to it in my first year at ECA [Edinburgh College of Art.] I don't remember ever having consciously thought about tapestry before that day but I somehow knew that eventually I'd be really good at this. From that day I have been able to plough a straight path deeper and deeper into tapestry, through my studies in Scotland and Poland, my 8 years as a studio weaver in England and Australia and since 1987 as an independent tapestry artist. The demanding creative ethos of the tapestry department gave me the confidence, motivation and self-discipline I needed to move out into the world as a professional tapestry weaver and artist. What was most inspiring for me as a young student was that my tutors in the department were all practising, exhibiting artists engaging positively with what was then a cutting edge international Fibre Art movement.[18]

Archie Brennan, now in his sixth decade of weaving, says of tapestry:

500 years ago it was already extremely sophisticated in its development-- aesthetically, technically and in diversity of purpose. Today, its lack of a defined purpose, its rarity, gives me an opportunity to seek new roles, to extend its historic language and, above all, to dominate my compulsive, creative drive. In 1967, I made a formal decision to step away from the burgeoning and exciting fiber arts movement and to refocus on woven tapestry’s long-established graphic pictorial role.[19]

.jpg)

Jacquard tapestries, colour and the human eye

The term tapestry is also used to describe weft-faced textiles made on Jacquard looms. Before the 1990s tapestry upholstery fabrics and reproductions of the famous tapestries of the Middle Ages had been produced using Jacquard techniques but more recently, artists such as Chuck Close, Patrick Lichty, and the workshop Magnolia Editions have adapted the computerised Jacquard process to producing fine art.[20] Typically, tapestries are translated from the original design via a process resembling paint-by-numbers: a cartoon is divided into regions, each of which is assigned a solid colour based on a standard palette. However, in Jacquard weaving, the repeating series of multicoloured warp and weft threads can be used to create colours that are optically blended – i.e., the human eye apprehends the threads’ combination of values as a single colour.[7]

This method can be likened to pointillism, which originated from discoveries made in the tapestry medium. The style's emergence in the 19th century can be traced to the influence of Michel Eugène Chevreul, a French chemist responsible for developing the colour wheel of primary and intermediary hues. Chevreul worked as the director of the dye works at Les Gobelins tapestry works in Paris, where he noticed that the perceived colour of a particular thread was influenced by its surrounding threads, a phenomenon he called “simultaneous contrast". Chevreul's work was a continuation of theories of colour elaborated by Leonardo da Vinci and Goethe; in turn, his work influenced painters including Eugène Delacroix and Georges-Pierre Seurat.

The principles articulated by Chevreul also apply to contemporary television and computer displays, which use tiny dots of red, green and blue (RGB) light to render colour, with each composite being called a pixel.[7]

List of famous tapestries

- The Trojan War tapestry referred to by Homer in Book III of the Iliad, where Iris disguises herself as Laodice and finds Helen "working at a great web of purple linen, on which she was embroidering the battles between Trojans and Achaeans, that Ares had made them fight for her sake." Though the composition of the Iliad spanned a period of approximately 700 years, it is worth noting that this method of weaving was in common use in or before the eighth century BC.

- The Cloth of St Gereon – second oldest European tapestry still extant.

- The Överhogdal tapestries - the oldest European tapestry still extant.

- The Sampul tapestry, woollen wall hanging, 3rd–2nd century BC, Sampul, Ürümqi Xinjiang Museum.

- The Hestia Tapestry, 6th century, Egypt, Dumbarton Oaks Collection.

- The Bayeux Tapestry is an embroidered cloth — not an actual tapestry — nearly 70 metres (230 ft) long, which depicts the events leading up to the Norman conquest of England, likely made in England — not Bayeux — in the 1070s

- The Apocalypse Tapestry depicts scenes from the Book of Revelation. It was woven between 1373 and 1382. Originally 140 m (459 ft), the surviving 100m are displayed in the Château d'Angers, in Angers.

- The six-part piece La Dame à la Licorne (The Lady and the Unicorn), stored in l'Hôtel de Cluny, Paris.

- The Devonshire Hunting Tapestries, four Flemish tapestries dating from the mid-fifteenth century depict men and women in fashionable dress of the early fifteenth century hunting in a forest. The tapestries formerly belonged to the Duke of Devonshire and are now in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

- The Justice of Trajan and Herkinbald, a tapestry dating from about 1450.

- The Triumph of Fame, a tapestry made in Flanders in the 1500s.

- The Hunt of the Unicorn is a seven piece tapestry from 1495 to 1505, currently displayed at The Cloisters, Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

- Les Chasses de Maximilien (The Hunts of Maximilian) is a series of twelve tapestries woven in Brussels after the designs of Bernard van Orley.

- The Life and miracles of St Adelphus, an early 16th-century cycle of tapestries (four surviving parts), total length 20 m (66 ft), in the Église Saint-Pierre-et-Saint-Paul, Neuwiller-lès-Saverne.

- The tapestries for the Sistine Chapel, designed by Raphael in 1515–16, for which the Raphael Cartoons, or painted designs, also survive.

- The Jagiellonian tapestries, (mid 16th century) a collection of 134 tapestries at the Wawel Castle in Kraków, Poland displaying various religious, natural, and royal themes. These famous tapestries, created in Arras, were collected by Polish Kings Sigismund I the Old and Sigismund II Augustus.

- The Valois Tapestries are a cycle of 8 hangings depicting royal festivities in France in the 1560s and 1570s

- The New World Tapestry is a 267 feet long tapestry which depicts the colonisation of the Americas between 1583 and 1648, displayed at the British Empire and Commonwealth Museum; this is not (strictly speaking) a tapestry, but is instead embroidery.

- The History of Constantine, a series of tapestries designed by Peter Paul Rubens and Italian artist Pietro da Cortona in 1622.

- The Death of Polydorus, one of a set of seven tapestries showing a scene from the Iliad by Homer.

- The biggest collection of Flanders tapestry is in the Spanish royal collection, there is 8000 metres of historical tapestry from Flanders, as well as Spanish tapestries designed by Goya and others. There is a special museum in the Royal Palace of La Granja de San Ildefonso, and others are displayed in various historic buildings.

- The Pastoral Amusements, also known as "Les Amusements champêtres", a series of 8 Beauvais Tapestries designed by Jean-Baptiste Oudry between 1720 and 1730.

- The Prestonpans Tapestry is a 104 metres long embroidery which tells the story of Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Battle of Prestonpans.

- Le Bouquet (1951) by Marc Saint-Saens is among the best and most representative French tapestries of the fifties. It is a tribute to Saint-Saens’s predilection for scenes from nature and rustic life. [21]

- Christ in Glory, (1962) for Coventry Cathedral designed by Graham Sutherland. Up until the 1990s this was the world's largest vertical tapestry.

- The World Trade Center Tapestry, a large 1973 tapestry]by Joan Miró and Josep Royo.

- The Quaker Tapestry (1981–1989) is a modern set of embroidery panels that tell the story of Quakerism from the 17th century to the present day.

- The Great Tapestry of Scotland is a modern series of embroidered cloths, made up of 160 hand stitched panels, depicting aspects of the history of Scotland from 8500 BC until 2013. At 143 metres (469 ft) long, it is the longest tapestry in the world.

References

Notes

- Mallet, Marla. "Basic Tribal and Village Weaves".

- Rivers, Shayne, and Nick Umney. Conservation of Furniture. Butterworth-Heinemann, 2003.

- Harper, Douglas. "tapestry". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- tapes. Charlton T. Lewis. An Elementary Latin Dictionary on Perseus Project.

- τάπης. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- "The Linear B word ta-pe-ja". Palaeolexicon. Word study tool for ancient Languages.

- Stone, Nick. "Jacquard Weaving and the Magnolia Tapestry Project" Archived 2009-01-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- Campbell, Henry VIII and the Art of Majesty, p. 339-341

- Olson, Rebecca (2013). Arras Hanging: The Textile That Determined Early Modern Literature and Drama. Newark: University of Delaware Press. ISBN 978-1611494686.

- Jean Lurçat Designing Tapestry Camelot Press, London 1950 p. 7

- Mathison, Fiona (2012). "Tapestry in the Modern Day". Tapestry: A Woven Narrative. Black Dog Publishing. pp. 28, 30. ISBN 9781907317248.

- 2 .Giselle Eberhard Cotton "The Lausanne International Tapestry Biennales (1962-1995) The Pivotal Role of a Swiss City in the 'New Tapestry' Movement' in Eastern Europe After World War II" Textile Society of America 13th Biennial Symposium, Washington DC 2012

- Jan Janeiro, "Northern California Textile Artists: 1939 – 1965" "The Fabric of Life: 150 years of Northern California Fiber Art History" San Francisco State University 1997 p.23

- http://americantapestryalliance.org/resources/regional-groups/

- https://www.mandalasbymaddie.us

- 4 Linda Rees, "Towards a Proactive Outreach Political Strings: Tapestry Seen and Unseen", Textile Society of America 13th Biennial Symposium, Washington DC 2012

- Susan Iverson "A Brief History of Teaching Tapestry" American Tapestry Alliance Tapestry Topics, Summer 2007 Vol 33 No 2. p.17

- "Joan Baxter". www.tapestrydepartment.co.uk.

- "Archie Brennan". www.tapestrydepartment.co.uk.

- Sheets, Hilarie M. "Looms with a View". Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- HENG, Michèle (1989), Marc Saint-Saens décorateur mural et peintre cartonnier de tapisserie, 1964 pages.

Bibliography

- Campbell, Thomas P. Henry VIII and the Art of Majesty: Tapestries at the Tudor Court, Yale University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-300-12234-3

- Russell, Carol K. Tapestry Handbook. The Next Generation, Schiffer Publ. Ltd., Atglen, PA. 2007, ISBN 978-0-7643-2756-8

- Embroidery and Tapestry Weaving, by Grace Christie, 1912, from Project Gutenberg. Technical handbook.

- Olson, Rebecca. Arras Hanging: The Textile That Determined Early Modern Literature and Drama, University of Delaware Press, 2013, ISBN 978-1611494686

Further reading

- Ortiz, A.; Carretero, C.; et al. (1991). Resplendence of the Spanish monarchy : Renaissance tapestries and armor from the Patrimonio Nacional. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Helena Hernmarck

- Tapestry is described both as an historic craft and a textile art. The West Dean College, Tapestry Symposium 2017, focused on this relationship between art and craft and has published presentations by the speakers.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tapestry. |

- Jagiellonian Tapestries Polish Tapestry Museum

- Tapestry, A World History of Art

- TAPESTRIES, HISTORY & STYLES by Lida Lavender

- Pictures from a contemporary mill, showing tapestries being woven on looms with Jacquard heads

- Goblan Ammar Arabic/Islamic tapestry art.

- Art Italian jacquard tapestry

- The West Dean College, Tapestry Studio