Poseidon

Poseidon (/pəˈsaɪdən, pɒ-, poʊ-/;[1] Greek: Ποσειδῶν, pronounced [poseːdɔ́ːn]) was one of the Twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and myth, god of the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses.[2] In pre-Olympian Bronze Age Greece, he was venerated as a chief deity at Pylos and Thebes.[2]. He had also the cult title "earth shaker". In the myths of isolated Arcadia he is related with Demeter and Persephone and he was venerated as a horse, however it seems that he was originally a god of the waters.[3] He is often regarded as the tamer or father of horses,[2] and with a strike of his trident, he created springs which are related with the word horse.[4] His Roman equivalent is Neptune.

| Poseidon | |

|---|---|

God of the sea, storms, earthquakes, horses | |

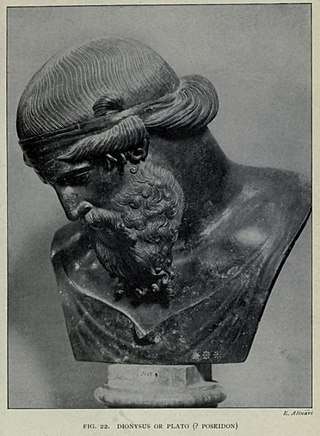

Poseidon from Milos, 2nd century BC (National Archaeological Museum of Athens) | |

| Abode | Mount Olympus, or the Sea |

| Symbol | Trident, fish, dolphin, horse, bull |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | Cronus and Rhea |

| Siblings | Hades, Demeter, Hestia, Hera, Zeus, Chiron |

| Consort | Amphitrite, Aphrodite, Demeter, various others |

| Children | Theseus Triton Polyphemus Orion Belus Agenor Neleus Atlas (the first king of Atlantis) Pegasus Chrysaor |

| Roman equivalent | Neptune |

Poseidon was protector of seafarers, and of many Hellenic cities and colonies. Homer and Hesiod suggest that Poseidon became lord of the sea following the defeat of his father Cronus, when the world was divided by lot among his three sons; Zeus was given the sky, Hades the underworld, and Poseidon the sea, with the Earth and Mount Olympus belonging to all three.[2][5]In Homer's Iliad, Poseidon supports the Greeks against the Trojans during the Trojan War and in the Odyssey, during the sea-voyage from Troy back home to Ithaca, the Greek hero Odysseus provokes Poseidon's fury by blinding his son, the Cyclops Polyphemus, resulting in Poseidon punishing him with storms, the complete loss of his ship and companions, and a ten-year delay. Poseidon is also the subject of a Homeric hymn. In Plato's Timaeus and Critias, the island of Atlantis was Poseidon's domain.[6][7][8]

Athena became the patron goddess of the city of Athens after a competition with Poseidon, and he remained on the Acropolis in the form of his surrogate, Erechtheus. After the fight, Poseidon sent a monstrous flood to the Attic Plain, to punish the Athenians for not choosing him. [9]

Etymology

The earliest attested occurrence of the name, written in Linear B, is 𐀡𐀮𐀆𐀃 Po-se-da-o or 𐀡𐀮𐀆𐀺𐀚 Po-se-da-wo-ne, which correspond to Ποσειδάων (Poseidaōn) and Ποσειδάϝονος (Poseidawonos) in Mycenean Greek; in Homeric Greek it appears as Ποσειδάων (Poseidaōn); in Aeolic as Ποτειδάων (Poteidaōn); and in Doric as Ποτειδάν (Poteidan), Ποτειδάων (Poteidaōn), and Ποτειδᾶς (Poteidas).[10] The form Ποτειδάϝων (Poteidawon) appears in Corinth.[11] A cult title of Poseidon in Linear B is E-ne-si-da-o-ne, "earth-shaker".

The origins of the name "Poseidon" are unclear. One theory breaks it down into an element meaning "husband" or "lord" (Greek πόσις (posis), from PIE *pótis) and another element meaning "earth" (δᾶ (da), Doric for γῆ (gē)), producing something like lord or spouse of Da, i.e. of the earth; this would link him with Demeter, "Earth-mother".[12] Walter Burkert finds that "the second element δᾶ- remains hopelessly ambiguous" and finds a "husband of Earth" reading "quite impossible to prove."[2] According to Robert Beekes,Etymological Dictionary of Greek, "there is no indication that δᾶ means 'earth'".[13] allthough the root da appears in the Linear B inscription E-ne-si-da-o-ne, "earth-shaker".[14][15]

Another, more plausible, theory interprets the second element as related to the (presumed) Doric word *δᾶϝον dâwon, "water", Proto-Indo-European *dah₂- "water" or *dʰenh₂- "to run, flow", Sanskrit दन् dā́-nu- "fluid, drop, dew" and names of rivers such as Danube (< *Danuvius) or Don. This would make *Posei-dawōn into the master of waters.[16] It seems that Poseidon was originally a god of the waters. [17] There is also the possibility that the word has Pre-Greek origin.[18] Plato in his dialogue Cratylus gives two traditional etymologies: either the sea restrained Poseidon when walking as a "foot-bond" (ποσίδεσμον), or he "knew many things" (πολλά εἰδότος or πολλά εἰδῶν).[19]

At least a few sources deem Poseidon as a "prehellenic" (i.e. Pelasgian) word, considering an Indo-European etymology "quite pointless".[20]

The name of the Frisian and Scandinavian god Fosite or Forseti, who was venerated on the island of Heligoland, may have been derived from Poseidon. According to the German philologist, Hans Kuhn, the Germanic form *Fosite is linguistically identical to Greek Poseidon. Roman altars dedicated to Poseidon have been found in the Middle Rhine area.

Bronze Age Greece

Linear B (Mycenean Greek) inscriptions

If surviving Linear B clay tablets can be trusted, the name po-se-da-wo-ne ("Poseidon") occurs with greater frequency than does di-u-ja ("Zeus"). A feminine variant, po-se-de-ia, is also found, indicating a lost consort goddess, in effect the precursor of Amphitrite. Poseidon carries frequently the title wa-na-ka (wanax) in Linear B inscriptions, as king of the underworld. The chthonic nature of Poseidon-Wanax is also indicated by his title E-ne-si-da-o-ne in Mycenean Knossos and Pylos,[21] a powerful attribute (earthquakes had accompanied the collapse of the Minoan palace-culture). In the cave of Amnisos (Crete) Enesidaon is related with the cult of Eileithyia, the goddess of childbirth.[22] She was related with the annual birth of the divine child.[23] During the Bronze Age, a goddess of nature, dominated both in Minoan and Mycenean cult, and Wanax (wa-na-ka) was her male companion (paredros) in Mycenean cult.[24] It is possible that Demeter appears as Da-ma-te in a Linear B inscription (PN EN 609), however the interpretation is still under dispute.[25]

In Linear B inscriptions found at Pylos, E-ne-si-da-o-ne is related with Poseidon, and Si-to Po-tini-ja is probably related with Demeter.[26] Tablets from Pylos record sacrificial goods destined for "the Two Queens and Poseidon" ("to the Two Queens and the King": wa-na-soi, wa-na-ka-te). The "Two Queens" may be related with Demeter and Persephone, or their precursors, goddesses who were not associated with Poseidon in later periods.[27]

Arcadian myths

The illuminating exception is the archaic and localised myth of the stallion Poseidon and mare Demeter at Phigalia in isolated and conservative Arcadia, noted by Pausanias (2nd century AD) as having fallen into desuetude; the stallion Poseidon pursues the mare-Demeter, and from the union she bears the horse Arion, and a daughter (Despoina), who obviously had the shape of a mare too. The violated Demeter was Demeter Erinys (furious) .[28] In Arcadia, Demeter's mare-form was worshiped into historical times. Her xoanon of Phigaleia shows how the local cult interpreted her, as goddess of nature. A Medusa type with a horse's head with snaky hair, holding a dove and a dolphin, probably representing her power over air and water.[29]

Origins

It seems that the Arcadian myth is related with the first Greek speaking people who entered the region during the Bronze Age. (Linear B represents an archaic Greek dialect). Their religious beliefs were mixed with the beliefs of the indigenous population. It is possible that the Greeks did not bring with them other gods except Zeus, Eos, and the Dioskouroi. The horse (numina) was related with the liquid element, and with the underworld. Poseidon appears as a beast (horse), which is the river spirit of the underworld, as it usually happens in northern-European folklore, and not unusually in Greece.[30][31] Poseidon "Wanax", is the male companion (paredros) of the goddess of nature. In the relative Minoan myth, Pasiphaë is mating with the white bull, and she bears the hybrid creature Minotaur.[32] The Bull was the old pre-Olympian Poseidon.[33] The goddess of nature and her paredros survived in the Eleusinian cult, where the following words were uttered: "Mighty Potnia bore a strong son".[34]

In the heavily sea-dependent Mycenaean culture, there is not sufficient evidence that Poseidon was connected with the sea. We do not know if "Posedeia" was a sea-goddess. Homer and Hesiod suggest that Poseidon became lord of the sea following the defeat of his father Cronus, when the world was divided by lot among his three sons; Zeus was given the sky, Hades the underworld, and Poseidon the sea, with the Earth and Mount Olympus belonging to all three.[2][35] Walter Burkert suggests that the Hellene cult worship of Poseidon as a horse god may be connected to the introduction of the horse and war-chariot from Anatolia to Greece around 1600 BC.[2]

There is evidence that Poseidon was once worshipped as a horse, and this is evident by his cult in Peloponnesos. However, some ancient writers held he was originally a god of the waters, and therefore he became the "earth-shaker", because the Greeks believed that the cause of the earthquakes was the erosion of the rocks by the waters, by the rivers who they saw to disappear into the earth and then to burst out again. This is what the natural philosophers Thales, Anaximenes and Aristotle believed, which may have been similar to the folklore belief.[36]

In any case, the early importance of Poseidon can still be glimpsed in Homer's Odyssey, where Poseidon rather than Zeus is the major mover of events. In Homer, Poseidon is the master of the sea.[37]

Worship of Poseidon

Poseidon was a major civic god of several cities: in Athens, he was second only to Athena in importance, while in Corinth and many cities of Magna Graecia he was the chief god of the polis.[2]

In his benign aspect, Poseidon was seen as creating new islands and offering calm seas. When offended or ignored, he supposedly struck the ground with his trident and caused chaotic springs, earthquakes, drownings and shipwrecks. Sailors prayed to Poseidon for a safe voyage, sometimes drowning horses as a sacrifice; in this way, according to a fragmentary papyrus, Alexander the Great paused at the Syrian seashore before the climactic battle of Issus, and resorted to prayers, "invoking Poseidon the sea-god, for whom he ordered a four-horse chariot to be cast into the waves."[38]

According to Pausanias, Poseidon was one of the caretakers of the oracle at Delphi before Olympian Apollo took it over. Apollo and Poseidon worked closely in many realms: in colonization, for example, Delphic Apollo provided the authorization to go out and settle, while Poseidon watched over the colonists on their way, and provided the lustral water for the foundation-sacrifice. Xenophon's Anabasis describes a group of Spartan soldiers in 400–399 BC singing to Poseidon a paean—a kind of hymn normally sung for Apollo. Like Dionysus, who inflamed the maenads, Poseidon also caused certain forms of mental disturbance. A Hippocratic text of ca 400 BC, On the Sacred Disease[39] says that he was blamed for certain types of epilepsy.

Poseidon is still worshipped today in modern Hellenic religion, among other Greek gods. The worship of Greek gods is recognized by the Greek government since 2017.[40][41]

Epithets

Common epithets (or adjectives) applied to Poseidon are Enosichthon (Ἐνοσίχθων) "Earth Shaker" or "earth-shaking" and Ennosigaios (Ἐννοσίγαιος), used by Homer in the Iliad and by Nonnus in Dionysiaca.[lower-alpha 1][42][43] Of the two phrases, Enosichthon has an older evidence of use, as it is identified in Linear B, as 𐀁𐀚𐀯𐀅𐀃𐀚, E-ne-si-da-o-ne,[21]

The epithets Ennosigaios (and Ennosidas), Gaiēochos (Γαιήοχος) ,Seisichthon ,[44] ,indicate the chthonic nature of Poseidon. In the town of Aegae in Euboea, he was known as Poseidon Aegaeus and had a magnificent temple upon a hill,[45][46][47] Epithets like Pelagios (Πελάγιος) "belonging to the sea" in Ionia, Phykios (φύκιος) "full of seaweed" in Mykonos[48] , "Kyanochetis" ,(κυανοχαίτης: "Dark-Haired", dark blue of the sea)[49], indicate that Poseidon was regarded as holding sway over land as well as the sea.[43]

Poseidon also had a close association with horses, known under the epithet Hippios(ἲππειος), usually in Arcadia. He is more often regarded as the tamer of horses, but in some myths he is their father, either by spilling his seed upon a rock or by mating with a creature who then gave birth to the first horse.[2] He was closely related with the springs, and with the strike of his trident, he created springs. Many springs like Hippocrene and Aganippe in Helikon are related with the word horse (hippos). (also Glukippe, Hyperippe).[50]

Some other epithets of Poseidon are:[51]

- "Asphaleios", (ασφάλεια: safety), as protector from the earthquakes.

- "Helikonios", (Ελικώνιος) related with the mountain Helikon.

- "Tavreios", (Ταύρειος: related with the bull). There was a fest "Tavreia" in Ephesos.

- "Petraios" ((Πετραἵος): related with rocks) in Thessaly. He hit a rock, and the horse "Skyphios" appeared.

- "Ptortheion" (Πτορθείων) "promotor of vegetation".

- "Epoptis" (επόπτης: supervisor) in Megalopolis

- "Phykios" (Φύκιος: related with seaweeds) in Mykonos.

- "Phytalmios" (Φυτάλμιος) related with the vegetation in Troizen, Megara, Rhodes.

- Epithets related with the genealogy trees: "Patrigenios", "Genethlios", "Genesios", "Pater", "Phratrios".

- "Epactaeus", meaning "god worshipped on the coast", in Samos.[52]

Birth

Poseidon was the second son of the Titans Cronus and Rhea. In most accounts he is swallowed by Cronus at birth and is later saved, along with his other brothers and sisters, by Zeus.

However, in some versions of the story, he, like his brother Zeus, did not share the fate of his other brother and sisters who were eaten by Cronus. He was saved by his mother Rhea, who concealed him among a flock of lambs and pretended to have given birth to a colt, which she gave to Cronus to devour.[53]

According to John Tzetzes[54] the kourotrophos, or nurse of Poseidon was Arne, who denied knowing where he was, when Cronus came searching; according to Diodorus Siculus[55] Poseidon was raised by the Telchines on Rhodes, just as Zeus was raised by the Korybantes on Crete.

According to a single reference in the Iliad, when the world was divided by lot in three, Zeus received the sky, Hades the underworld and Poseidon the sea.[56]

In Homer's Odyssey (Book V, ln. 398), Poseidon has a home in Aegae.

Foundation of Athens

Athena became the patron goddess of the city of Athens after a competition with Poseidon. Yet Poseidon remained a numinous presence on the Acropolis in the form of his surrogate, Erechtheus.[2] At the dissolution festival at the end of the year in the Athenian calendar, the Skira, the priests of Athena and the priest of Poseidon would process under canopies to Eleusis.[57] They agreed that each would give the Athenians one gift and the Athenians would choose whichever gift they preferred. Poseidon struck the ground with his trident and a spring sprang up; the water was salty and not very useful,[58] whereas Athena offered them an olive tree.

The Athenians or their king, Cecrops, accepted the olive tree and along with it Athena as their patron, for the olive tree brought wood, oil and food. After the fight, infuriated at his loss, Poseidon sent a monstrous flood to the Attic Plain, to punish the Athenians for not choosing him. The depression made by Poseidon's trident and filled with salt water was surrounded by the northern hall of the Erechtheum, remaining open to the air. "In cult, Poseidon was identified with Erechtheus," Walter Burkert noted; "the myth turns this into a temporal-causal sequence: in his anger at losing, Poseidon led his son Eumolpus against Athens and killed Erectheus."[59]

The contest of Athena and Poseidon was the subject of the reliefs on the western pediment of the Parthenon, the first sight that greeted the arriving visitor.

This myth is construed by Robert Graves and others as reflecting a clash between the inhabitants during Mycenaean times and newer immigrants. Athens at its height was a significant sea power, at one point defeating the Persian fleet at Salamis Island in a sea battle.

Walls of Troy

Poseidon and Apollo, having offended Zeus by their rebellion in Hera's scheme, were temporarily stripped of their divine authority and sent to serve King Laomedon of Troy. He had them build huge walls around the city and promised to reward them well, a promise he then refused to fulfill. In vengeance, before the Trojan War, Poseidon sent a sea monster to attack Troy. The monster was later killed by Heracles.

Consorts and children

Poseidon was said to have had many lovers of both sexes (see expandable list below). His consort was Amphitrite, a nymph and ancient sea-goddess, daughter of Nereus and Doris. Together they had a son named Triton, a merman.

Poseidon was the father of many heroes. He is thought to have fathered the famed Theseus.

A mortal woman named Tyro was married to Cretheus (with whom she had one son, Aeson), but loved Enipeus, a river god. She pursued Enipeus, who refused her advances. One day, Poseidon, filled with lust for Tyro, disguised himself as Enipeus, and from their union were born the heroes Pelias and Neleus, twin boys. Poseidon also had an affair with Alope, his granddaughter through Cercyon, his son and King of Eleusis, begetting the Attic hero Hippothoon. Cercyon had his daughter buried alive but Poseidon turned her into the spring, Alope, near Eleusis.

Poseidon rescued Amymone from a lecherous satyr and then fathered a child, Nauplius, by her.

After having raped Caeneus, Poseidon fulfilled her request and changed her into a male warrior.

A mortal woman named Cleito once lived on an isolated island; Poseidon fell in love with the human mortal and created a dwelling sanctuary at the top of a hill near the middle of the island and surrounded the dwelling with rings of water and land to protect her. She gave birth to five sets of twin boys; the firstborn, Atlas, became the first ruler of Atlantis.[6][7][8]

Not all of Poseidon's children were human. In an archaic myth, Poseidon once pursued Demeter. She spurned his advances, turning herself into a mare so that she could hide in a herd of horses; he saw through the deception and became a stallion and captured her. Their child was a horse, Arion, which was capable of human speech. Poseidon also raped Medusa on the floor of a temple to Athena.[60][61] Medusa was then changed into a monster by Athena.[62][61] When she was later beheaded by the hero Perseus, Chrysaor and Pegasus emerged from her neck.

His other children include Polyphemus (the Cyclops) and, finally, Alebion and Bergion and Otos and Ephialtae (the giants).[60]

List of Poseidon's consorts and children

Female lovers and offspring

| Goddesses | Children | Mortal Women | Children | Mortal Women | Children |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amphitrite | • Triton | Agamede | • Dictys | Laodice[63] | No known offspring |

| • Benthesikyme | • Actor | Larissa | • Achaeus | ||

| • Rhodos | Aethra | • Theseus | • Pelasgus | ||

| Gaea | • Antaeus | Alistra[64] | • Ogygus | • Pythius | |

| • Charybdis | Alope | • Hippothoon | Leis, daughter of Orus | • Altephus, king of Troezen[65] | |

| • Laistryon | Amphimedusa | • Erythras[66] | Libya | • Agenor | |

| Demeter | • Despoina | Amymone | • Nauplius | • Belus | |

| • Areion | Anippe or | • Busiris | • Lelex | ||

| Aphrodite | • Rhodos | Lysianassa | Melantho | • Delphus | |

| • Herophile (possibly) | Arene | • Idas (possibly) | Melissa[67] | • Dyrrhachius[68] | |

| Medusa | • Pegasus | Arne or | • Aeolus | Melite | • Metus[69] |

| • Chrysaor | Melanippe | • Boeotus | Mestra | No known offspring | |

| Unknown mother | • Cymopoleia | Ascre | • Oeoclus[70] | Molione | • The Molionides |

| Nymphs | Children | Astypalaea | • Ancaeus | 1. Cteatus | |

| Aba | • Ergiscus[71] | • Eurypylus | 2. Eurytus | ||

| Alcyone | • Aethusa | Boudeia / Bouzyge | • Erginus | Mytilene | • Myton[72] |

| • Hyrieus | Caenis | No known offspring | Oenope | • Megareus (possibly) | |

| • Hyperenor | Calchinia | • Peratus | Ossa | • Sithon (possibly) | |

| • Hyperes | Calyce or | • Cycnus | Periboea | • Nausithous | |

| • Anthas | Harpale or | Phoenice | • Torone[73] | ||

| Arethusa | • Abas | Scamandrodice | • Proteus | ||

| Bathycleia[74] or | • Halirrhothius | a Nereid[75] | Rhode[76] | • Ialysus | |

| Euryte[77] | Canace | • Hopleus | • Cameirus | ||

| Beroe | No known offspring | • Nireus | • Lindus | ||

| Bisalpis or | • Chrysomallus | • Aloeus | Syme | • Chthonius | |

| Bisaltis or | • Epopeus | Themisto | • Leucon or Leuconoe | ||

| Theophane | • Triopas | Tyro | • Pelias | ||

| Celaeno[78] | • Lycus | Celaeno | • Celaenus | • Neleus | |

| • Nycteus | Cerebia[79] | • Dictys | Daughter of Amphictyon | • Cercyon | |

| • Eurypylus (Eurytus) | • Polydectes | Unknown Woman | • Dicaeus[80] | ||

| • Lycaon | Ceroessa | • Byzas | • Syleus | ||

| Kelousa or | • Asopus (possibly) | Chrysogeneia | • Chryses | Unknown Woman | • Amphimarus[81] |

| Pero | Circe | • Phaunos | Unknown Woman | • Amyrus[82] | |

| Cleodora | • Parnassus | Cleito[83] | • Ampheres | Unknown Woman | • Aon, eponym of Aonia[84] |

| Chione | • Eumolpus | • Atlas | Unknown Mother | • Astraeus of Mysia[85] | |

| Corcyra | • Phaeax | • Autochthon | • Alcippe of Mysia[85] | ||

| Diopatra | No known offspring | • Azaes | Unknown Woman | • Augeas[86] | |

| Halia | • Rhode (possibly) | • Diaprepes | Unknown Woman | • Beergios[75] | |

| • Six sons | • Elasippus | Unknown Woman | • Byzenus[75] | ||

| Melantheia | • Eirene[87] | • Euaemon | Unknown Woman | • Calaurus[88] | |

| Melia | • Amycus | • Eumelus (Gadeirus) | Unknown Woman | • Caucon or Glaucon[89] | |

| • Mygdon | • Mestor | Unknown Woman | • Corynetes (possibly) | ||

| Mideia | • Aspledon | • Mneseus | Unknown Woman | • Cromus, eponym of Crommyon[90] | |

| Olbia | • Astacus[91] | Coronis | No known offspring | Unknown Woman | • Dercynus (Bergion) of Liguria[92] |

| Peirene | • Cenchrias | Eidothea | • Eusiros[93] | Unknown Woman | • Eryx, king of Eryx in Sicily |

| • Leches | Ergea | Celaeno | Unknown Woman | • Euseirus, father of Cerambus | |

| Pitane or | • Euadne | Europa or | • Euphemus | Unknown Woman | • Geren[94] |

| Lena | Mecionice | Unknown Woman | • Ialebion (Alebion) of Liguria[92] | ||

| Pronoe | • Phocus | Euryale | • Orion | Unknown Woman | • Lamus, king of the Laestrygonians |

| Rhodope | • Athos[95] | Eurycyda | • Eleius | Unknown Woman | • Messapus |

| Salamis | • Cychreus | Eurynome (Eurymede) | • Bellerophon | Unknown Woman | • Onchestus[96] |

| Satyria of Taras | • Taras[97] | Helle | • Almops | Unknown Woman | • Palaestinus[98] |

| Thoosa | • Polyphemus | • Edonus | Unknown Woman | • Phineus[99] | |

| Thyia | No known offspring | • Paion | Unknown Woman | • Phorbas of Acarnania | |

| Nymph of Chios | • Chios | Hermippe | • Minyas (possibly) | Unknown Woman | • Poltys |

| Nymph of Chios

(another one) |

• Melas | Hippothoe | • Taphius | Unknown Woman | • Procrustes |

| • Agelus | Iphimedeia | • The Aloadae | Unknown Woman | • Sarpedon of Ainos | |

| • Malina | 1. Ephialtes | Unknown Woman | • Sciron | ||

| Unknown mother | • Lotis (possibly) | 2. Otus | Unknown Woman | • Taenarus (possibly) | |

| Unknown mother | • Ourea, a nymph[100] | Lamia | • Sibylla (Sibyl) | Unknown Woman | • Terambos |

| Unknown Woman | • Thasus |

Male lovers

Genealogy

| Poseidon's family tree [102] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In literature and art

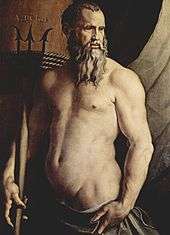

In Greek art, Poseidon rides a chariot that was pulled by a hippocampus or by horses that could ride on the sea. He was associated with dolphins and three-pronged fish spears (tridents). He lived in a palace on the ocean floor, made of coral and gems.

In the Iliad Poseidon favors the Greeks, and on several occasion takes an active part in the battle against the Trojan forces. However, in Book XX he rescues Aeneas after the Trojan prince is laid low by Achilles.

In the Odyssey, Poseidon is notable for his hatred of Odysseus who blinded the god's son, the Cyclops Polyphemus. The enmity of Poseidon prevents Odysseus's return home to Ithaca for many years. Odysseus is even told, notwithstanding his ultimate safe return, that to placate the wrath of Poseidon will require one more voyage on his part.

In the Aeneid, Neptune is still resentful of the wandering Trojans, but is not as vindictive as Juno, and in Book I he rescues the Trojan fleet from the goddess's attempts to wreck it, although his primary motivation for doing this is his annoyance at Juno's having intruded into his domain.

A hymn to Poseidon included among the Homeric Hymns is a brief invocation, a seven-line introduction that addresses the god as both "mover of the earth and barren sea, god of the deep who is also lord of Helicon and wide Aegae,[108] and specifies his twofold nature as an Olympian: "a tamer of horses and a saviour of ships."

Poseidon appears in Percy Jackson and the Olympians as the father of Percy Jackson and Tyson the Cyclops. He also appears in the ABC television series Once Upon a Time as the guest star of the second half of season four played by Ernie Hudson.[109] In this version, Poseidon is portrayed as the father of the Sea Witch Ursula.

Narrations

- Poseidon myths as told by story tellers

Bibliography of reconstruction:

- Homer, Odyssey, 11.567 (7th century BC)

- Pindar, Olympian Odes, 1 (476 BC)

- Euripides, Orestes, 12–16 (408 BC)

- Bibliotheca Epitome 2: 1–9 (140 BC)

- Ovid, Metamorphoses, VI: 213, 458 (AD 8);

- Hyginus, Fables, 82: Tantalus; 83: Pelops (1st century AD)

- Pausanias, Description of Greece, 2.22.3 (AD 160 – 176)

Bibliography of reconstruction:

- Pindar, Olympian Ode, I (476 BC)

- Sophocles, (1) Electra, 504 (430 – 415 BC) & (2) Oenomaus, Fr. 433 (408 BC)

- Euripides, Orestes, 1024–1062 (408 BC)

- Bibliotheca Epitome 2, 1–9 (140 BC)

- Diodorus Siculus, Histories, 4.73 (1st century BC)

- Hyginus, Fables, 84: Oinomaus; Poetic Astronomy, ii (1st century AD)

- Pausanias, Description of Greece, 5.1.3 – 7; 5.13.1; 6.21.9; 8.14.10 – 11 (c. AD 160 – 176)

- Philostratus the Elder Imagines, I.30: Pelops (AD 170 – 245)

- Philostratus the Younger, Imagines, 9: Pelops (c. 200 – 245)

- First Vatican Mythographer, 22: Myrtilus; Atreus et Thyestes

- Second Vatican Mythographer, 146: Oenomaus

Gallery

Paintings

Poseidon holding a trident. Corinthian plaque, 550-525 BC. From Penteskouphia.

Poseidon holding a trident. Corinthian plaque, 550-525 BC. From Penteskouphia. Poseidon on an Attic kalyx krater (detail), first half of the 5th century BC.

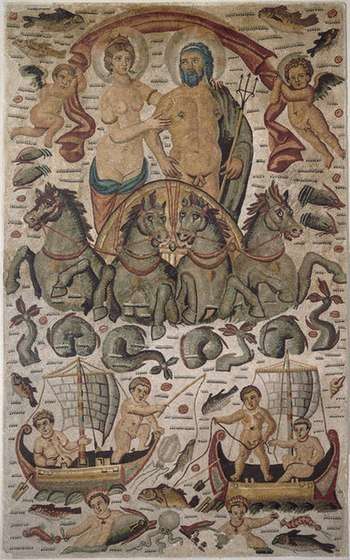

Poseidon on an Attic kalyx krater (detail), first half of the 5th century BC. Triumph of Poseidon and Amphitrite showing the couple in procession, detail of a vast mosaic from Cirta, Roman Africa (ca. 315–325 AD, now at the Louvre)

Triumph of Poseidon and Amphitrite showing the couple in procession, detail of a vast mosaic from Cirta, Roman Africa (ca. 315–325 AD, now at the Louvre).jpg) Poseidon and Athena battle for control of Athens by Benvenuto Tisi(1512)

Poseidon and Athena battle for control of Athens by Benvenuto Tisi(1512)

Statues

Poseidon statue in Gothenburg, Sweden.

Poseidon statue in Gothenburg, Sweden.

The Neptunbrunnen fountain in Berlin

The Neptunbrunnen fountain in Berlin Poseidon sculpture in Copenhagen, Denmark

Poseidon sculpture in Copenhagen, Denmark

See also

- Atlantis

- Ionian League

- Panionium – Ionian festival to Poseidon

- Odyssey

- Trident of Poseidon

Explanatory notes

References

- Citations

- Jones, Daniel (2003) [1917], Peter Roach; James Hartmann; Jane Setter (eds.), English Pronouncing Dictionary, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-3-12-539683-8

- Burkert 1985, pp. 136–139.

- Seneca quaest. Nat. VI 6 :Nilsson Vol I p.450

- Nilsson Vol I p.450

- Hesiod, Theogony 456.

- Plato (1971). Timaeus and Critias. London, England: Penguin Books Ltd. pp. 167. ISBN 9780140442618.

- Timaeus 24e–25a, R. G. Bury translation (Loeb Classical Library).

- Also it has been interpreted that Plato or someone before him in the chain of the oral or written tradition of the report accidentally changed the very similar Greek words for "bigger than" ("meson") and "between" ("mezon") – Luce, J.V. (1969). The End of Atlantis – New Light on an Old Legend. London: Thames and Hudson. p. 224.

- Burkert 1983, pp. 149, 157.

- Martin Nilsson (1967). Die Geschichte der Griechische Religion. Erster Band. Verlag C. H. Beck. p. 444.

- Liddell & Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, Ποσειδῶν Archived 9 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- Pierre Chantraine Dictionnaire etymologique de la langue grecque Paris 1974–1980 4th s.v.; Lorenzo Rocci Vocabolario Greco-Italiano Milano, Roma, Napoli 1943 (1970) s.v.

- R. S. P. Beekes. Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. 324 (s.v. "Δημήτηρ")

- Δημήτηρ. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; An Intermediate Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- Adams, John Paul, Mycenean divinities – List of handouts for California State University Classics 315. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- Martin Nilsson, p. 417, p. 445. Michael Janda, pp. 256-258.

- "The Greeks believed that the cause of the earthquakes was the erosion of the rocks by the waters" : Seneca quaest. Nat. VI 6 :Nilsson Vol I p.450

- Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, p. 324.

- Plato, Cratylus, 402d–402e

- van der Toorn, Karel; Becking, Bob; van der Horst, Pieter Willem (1999), Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible (second ed.), Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdman's Publishing Company, ISBN 0-8028-2491-9

- Adams, John Paul. "Mycenaean Divinities". List of Handouts for Classics 315. Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2006.

- Dietrich, pp. 220 Archived 23 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine–221 Archived 24 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- Dietrich, p. 109 Archived 23 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- Dietrich, p. 181 Archived 23 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- Ventris/Chadwick,Documents in Mycenean Greek p. 242; Dietrich, p. 172, n. 218 Archived 24 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- George Mylonas (1966), Mycenae and the Mycenean world. p.159. Princeton University Press

- "Wa-na-ssoi, wa-na-ka-te, (to the two queens and the king). Wanax (Greek : Αναξ) is best suited to Poseidon, the special divinity of Pylos. The identity of the two divinities addressed as wanassoi, is uncertain ": George Mylonas (1966) Mycenae and the Mycenean age p. 159 .Princeton University Press

- Pausanias VIII 23. 5; Raymond Bloch "Quelques remarques sur Poseidon, Neptunus et Nethuns" in Comptes-rendus des séances de l' Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Letres 2 1981 p. 345.

- L. H. Jeffery (1976). Archaic Greece: The Greek city states c.800-500 B.C (Ernest Benn Limited) p 23 ISBN 0-510-03271-0

- F.Schachermeyer: Poseidon und die Entstehung des Griechischen Gotter glaubens :Nilsson p 444

- The river god Acheloos is represented as a bull

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheke 3.1.4 Archived 4 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Ruck and Staples 1994:213.

- Dietrich, p. 167 Archived 23 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Hesiod, Theogony 456.

- Seneca quaest. Nat. VI 6 :Nilsson Vol I p.450

- "Poseidon – God of the Sea". www.crystalinks.com. Archived from the original on 11 November 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- Karl Wilhelm Ludwig Müller's ed. Papyrus Oxyrrhincus Fragmenta Historicorum Graecorum 148, 44, col. 2; quoted by Robin Lane Fox, Alexander the Great (1973) 1986:168 and note. Alexander also invoked other sea deities: Thetis, mother of his hero Achilles, Nereus and the Nereids

- "(Hippocrates), On the Sacred Disease, Francis Adams, tr". Archived from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- Brunwasser, Matthew (20 June 2013). "The Greeks Who Worship Ancient Gods". BBC. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- Souli, Sarah (4 January 2018). "Greece's Old Gods Are Ready for Your Sacrifice". The Outline. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- Ἐνοσίχθων; Ἐννοσίγαιος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- Smith, >Steven D. (2019), Maria Kanellou; Ivana Petrovic; Chris Carey (eds.), "Art, Nature, Power: Garden Epigrams from Nero to Heraclius", Greek Epigram from the Hellenistic to the Early Byzantine Era, Oxford University Press, p. 348, ISBN 978-0-192-57379-7

- Ennosidas (Pindar), Ennosigaios (Homer): Dietrich, p. 185 n. 305.

- Strabo, ix. p. 405

- Virgil, Aeneid iii. 74, where Servius erroneously derives the name from the Aegean Sea

- Schmitz, Leonhard (1867). "Aegaeus". In Smith, William (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. 1. Boston. p. 24.

- Nilsson, Vol I pp. 446–450

- Κυανοχαίτης. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- Nilsson Vol I p.450

- Nilsson, Vol I pp. 446–450

-

- In the 2nd century AD, a well with the name of Arne, the "lamb's well", in the neighbourhood of Mantineia in Arcadia, where old traditions lingered, was shown to Pausanias. (Pausanias, VIII.8.2.)

- Tzetzes, ad Lycophron 644.

- Diodorus, Bibliotheca Historica (Book V, Ch. 55.

- Homer's Iliad (Book XV, ln. 184-93 Archived 11 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine)

- Burkert 1983, pp. 143–149.

- Another version of the myth says that Poseidon gave horses to Athens.

- Burkert 1983, pp. 149, 157.

- Gill, N.S. (2007). "Mates and Children of Poseidon". Archived from the original on 23 December 2006. Retrieved 5 February 2007.

- Seelig 2002, p. 895-911.

- Philip Freeman (2013). Oh My Gods: A Modern Retelling of Greek and Roman Myths. p. 30. ISBN 9781451609981.

- Ovid, Heroides, 18 (19). 135

- Tzetzes on Lycophron, 1206

- Pausanias, Description of Greece, 2. 30. 5

- Scholia on Homer, Iliad, 2. 499

- daughter of Epidamnus

- Stephanus of Byzantium s. v. Dyrrhakhion

- Hyginus. Fabulae, 157 Archived 29 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- Pausanias, Description of Greece, 9. 29. 1

- Suida, Suda Encyclopedia s.v. Ergiske

- Stephanus of Byzantium s. v. Mytilene

- Stephanus of Byzantium s. v. Torōnē

- Scholia on Pindar. Olympian Ode 10.83 quoted in Hesiod. Catalogue of Women, fr.64

- Murray, John (1833). A Classical Manual, being a Mythological, Historical and Geographical Commentary on Pope's Homer, and Dryden's Aeneid of Virgil with a Copious Index. Albemarle Street, London. p. 78.

- Tzetzes on Lycophron, 923

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 3.14.2

- also said to be the daughter of Ergeus

- Tzetzes on Lycophron, 838

- eponym of Dicaea, a city in Thrace as cited in Stephanus of Byzantium s. v. Dikaia

- Pausanias, Description of Greece, 9. 29. 5

- eponym of a river in Thessaly as cited in Scholia on Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica, 1. 596

- In Plato, Critias, 114c: Myth of Atlantis, Poseidon consorted with Cleito, daughter of the autochthons Evenor and Leucippe, and had by her ten sons.

- Scholia on Statius, Thebaid, 1. 34

- Pseudo-Plutarch, On Rivers, 21. 1

- Bibliotheca 2.88 Archived 8 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine.

- Plutarch, Quaestiones Graecae, 19

- Stephanus of Byzantium s. v. Kalaureia

- Aelian, Various Histories, 1. 24

- Pausanias, Description of Greece, 2. 1. 3

- Stephanus of Byzantium, s. v. Astakos, with a reference to Arrian

- Bibliotheca 2. 5. 10

- Antoninus Liberalis. Metamorphoses, 22 vs Cerambus Archived 2 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- eponym of a town or village Geren on Lesbos as cited in Stephanus of Byzantium s. v. Gerēn

- Scholia on Theocritus, Idyll 7. 76

- Pausanias, Description of Greece, 9. 26. 5

- Probus on Virgil's Georgics, 2. 197

- Pseudo-Plutarch, On Rivers, 11. 1

- Pseudo-Apollodorus. Bibliotheca, Book 1.9.21

- Hyginus, Fabulae, 161

- Ptolemy Hephaestion, New History, 1 in Photius, 190

- This chart is based upon Hesiod's Theogony, unless otherwise noted.

- According to Homer, Iliad 1.570–579, 14.338, Odyssey 8.312, Hephaestus was apparently the son of Hera and Zeus, see Gantz, p. 74.

- According to Hesiod, Theogony 927–929 Archived 5 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Hephaestus was produced by Hera alone, with no father, see Gantz, p. 74.

- According to Hesiod, Theogony 886–890 Archived 5 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine, of Zeus' children by his seven wives, Athena was the first to be conceived, but the last to be born; Zeus impregnated Metis then swallowed her, later Zeus himself gave birth to Athena "from his head", see Gantz, pp. 51–52, 83–84.

- According to Hesiod, Theogony 183–200 Archived 5 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Aphrodite was born from Uranus' severed genitals, see Gantz, pp. 99–100.

- According to Homer, Aphrodite was the daughter of Zeus (Iliad 3.374, 20.105 Archived 2 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine; Odyssey 8.308 Archived 2 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine, 320) and Dione (Iliad 5.370–71), see Gantz, pp. 99–100.

- The ancient palace-city that was replaced by Vergina

- Andreeva, Nellie (19 December 2014). "Ernie Hudson To Play Poseidon On 'Once Upon a Time'". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on 24 December 2014. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- Bibliography

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Poseidon. |

- Burkert, Walter (1983), Homo Necans, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles. 1983. ISBN 978-0-520-05875-0.

- Burkert, Walter (1985), Greek Religion, Wiley-Blackwell 1985. ISBN 978-0-631-15624-6.

- Dietrich, B. C., The Origins of Greek Religion, Bristol Phoenix Press, 2004. ISBN 978-1-904675-31-0.

- Gantz, Timothy, Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, Two volumes: ISBN 978-0-8018-5360-9 (Vol. 1), ISBN 978-0-8018-5362-3 (Vol. 2).

- GML Poseidon

- Gods found in Mycenaean Greece; a table drawn up from Michael Ventris and John Chadwick, Documents in Mycenaean Greek second edition (Cambridge 1973)

- Hesiod, Theogony, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, Massachusetts., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Homer, The Iliad with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PhD in two volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Homer; The Odyssey with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PH.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1919. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Michael Janda, Eleusis. Das indogermanische Erbe der Mysterien, Innsbruck 2000, pp. 256–258 (Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Sprachwissenschaft, vol. 96)

- Jenks, Kathleen (April 2003). "Mythic themes clustered around Poseidon/Neptune". Myth*ing links. Archived from the original on 27 September 2006. Retrieved 13 January 2007.

- Seelig, Beth J. (August 2002), "The Rape of Medusa in the Temple of Athena: Aspects of Triangulation in the Girl", The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 83 (4): 895–911, doi:10.1516/3NLL-UG13-TP2J-927M

External links

- Theoi.com: Poseidon