Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus

The Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus is a marble Early Christian sarcophagus used for the burial of Junius Bassus, who died in 359. It has been described as "probably the single most famous piece of early Christian relief sculpture."[1] The sarcophagus was originally placed in or under Old St. Peter's Basilica, was rediscovered in 1597,[2] and is now below the modern basilica in the Museo Storico del Tesoro della Basilica di San Pietro (Museum of Saint Peter's Basilica) in the Vatican. The base is approximately 4 x 8 x 4 feet.

Together with the Dogmatic sarcophagus in the same museum, this sarcophagus is one of the oldest surviving high-status sarcophagi with elaborate carvings of Christian themes, and a complicated iconographic programme embracing the Old and New Testaments.

Junius Bassus

Junius Bassus was an important figure, a senator who was in charge of the government of the capital as praefectus urbi when he died at the age of 42 in 359. His father had been Praetorian prefect, running the administration of a large part of the Western Empire. Bassus served under Constantius II, son of Constantine I. Bassus, as the inscription on the sarcophagus tells us, converted to Christianity shortly before his death – perhaps on his deathbed. Many still believed, like Tertullian, that it was not possible to be an emperor and a Christian, which also went for the highest officials like Bassus.

Style

The style of the work has been greatly discussed by art historians, especially as its date is certain, which is unusual at this period.[3] All are agreed that the workmanship is of the highest quality available at the time, as one might expect for the tomb of such a prominent figure.

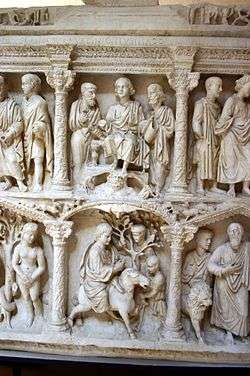

The sarcophagus in many respects shows fewer features of the Late Antique style of sculpture typified in the Arch of Constantine of several decades earlier: "The sculpture ignores practically all the rules obeyed by official reliefs. Some figures are portrayed frontally, but certainly not all, and they are not shown in a thoroughly Late Antique manner; the scenes are three-dimensional and have depth and background .... drapery hangs on recognizable human forms rather than being arranged in predetermined folds; heads are varied, portraying recognisably different people."[4] The sarcophagus has been seen as reflecting a blending of late Hellenistic style with the contemporary Roman or Italian one, seen in the "robust" proportions of the figures, and their slightly over-large heads.

The setting in the niches casts the figures against a background of shadow, giving "an emphatic chiaroscuro effect"[5] – an effect much more noticeable in the original than the cast shown here, which has a more uniform and lighter colour. The cast also lacks the effects created by light on polished or patinated highlights such as the heads of the figures, against the darker recessed surfaces and backgrounds.

Ernst Kitzinger finds "a far more definite reattachment to aesthetic ideals of the Graeco-Roman past" than in the earlier Dogmatic Sarcophagus and that of the "Two Brothers", also in the Vatican Museums.[6] The form continues the increased separation of the scenes; it had been an innovation of the earliest Christian sarcophagi to combine a series of incidents in one continuous (and rather hard to read) frieze, and also to have two registers one above the other, but these examples show a trend to differentiate the scenes, of which the Junius Bassus is the culmination, producing a "multitude of miniature stages", which allow the spectator "to linger over each scene", which was not the intention of earlier reliefs which were only "shorthand pictographs" of each scene, only intended to identify them.[7] He notes a "lyrical, slightly sweet manner" in the carving, even in the soldiers who lead St Peter to his death, which compares to some small carvings from the Hellenized east in the Cleveland Museum of Art, though they are several decades older.[8] Even allowing for "the gradual appropriation of a popular type of Christian tomb by upper-class patrons whose standards asserted themselves increasingly both in the content and in the style of these monuments", Kitzinger concludes that the changes must reflect a larger "regeneration" in style.[9]

Iconography

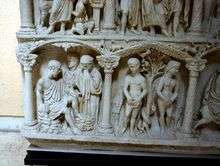

The carvings are in high relief on three sides of the sarcophagus, allowing for its placement against a wall. The column and many parts of the figures are carved completely in the round. The arrangement of relief scenes in rows in a columnar framework is an introduction from Asia Minor at about this time.[10] No portrait of the deceased is shown, though he is praised in lavish terms in an inscription; instead, the ten niches are filled with scenes from both the New and Old Testaments, plus one, the Traditio Legis, that has no Scriptural basis.

The scenes on the front are:[11] in the top row, Sacrifice of Isaac, Judgement or Arrest of Peter, Enthroned Christ with Peter and Paul (Traditio Legis), and a double scene of the Trial of Jesus before Pontius Pilate, who in the last niche is about to wash his hands. In the bottom row: Job on the dunghill, Adam and Eve, Christ's entry into Jerusalem, Daniel in the lion's den (heads restored), Arrest or leading to execution of Paul.

The tiny spandrels above the lower row show scenes with all participants depicted as lambs: on either side of Christ entering Jerusalem are the Miracle of the loaves and fishes and the Baptism of Jesus.[12] The other scenes may be the Three youths in the fiery furnace, the Raising of Lazarus, Moses receiving the tablets and Moses striking the rock.[13]

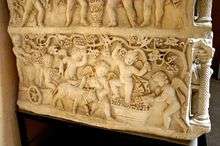

The sides have more traditional Roman scenes of the Four Seasons represented by putti performing seasonal tasks such as harvesting grapes. On a damaged plaque surmounting the lid is a poem praising Bassus in largely secular terms, and the inscription running along the top of the body of the sarcophagus identifies him, and describes him as a "neophyte", or recent convert. Further small reliefs on the lid, and heads at the corners, are badly damaged.[14] They showed scenes of feasts and a burial procession typical of pagan sarcophagi;[15] it is possible the lid was not created to match the base.

Scenes with Christ

The emphasis on scenes of judgement may have been influenced by the career of Bassus as a magistrate, but all the scenes shown can be paralleled in other Christian works of the period.

In all the three scenes where he appears Christ is a youthful, beardless figure with shortish hair (though longer than that of other figures), which is typical of Christian art at this period. The angel standing behind Abraham in the Sacrifice of Isaac is depicted similarly, and without wings. Christ appears in the centre of both rows; in the top row as a law-giver or teacher between his chief followers, Peter and Paul (the Traditio Legis), and on the bottom entering Jerusalem. Both scenes borrow from pagan Roman iconography: in the top one Jesus is sitting with his feet on a billowing cloak representing the sky, carried by Caelus, the classical personification of the heavens. Christ hands Peter a scroll, probably representing the Gospels, as emperors were often shown doing to their heirs, ministers or generals.[16]

Before Pilate Christ also carries a scroll, like a philosopher.[17] Pilate, perhaps worried by Jesus's reputation for miracles, is making the gesture Italians still use to ward off the evil eye.[18] Pilate has a mild and passive appearance, contrasting strongly with the powerful and determined expression of the figure in low relief profile behind him on the wall, the only figure in these scenes depicted in this style and technique. If he is not just one of Pilate's subordinate officers, he may be intended as a portrait or statue of the emperor; Roman official business was usually conducted before such an image, upon which (under the deified pagan emperors) any oaths required were made.

The lower scene loosely follows the entry ("adventus") of an emperor to a city, a scene often depicted in Imperial art; Christ is "identified as imperator by the imperial eagle of victory" in the conch moulding above the scene.[19] There was already a tradition, borrowed from pagan iconography, of depicting Christ the Victor; in this work that theme is linked to the Passion of Jesus, of which the entry to Jerusalem is the start,[20] a development that was to play a great part in shaping the Christian art of the future.

The inclusion of the pagan figure of Caelus may seem strange, but he was not an important figure in Ancient Roman religion, so was evidently considered as a harmless pictorial convention by the Christian designer of the composition, as well as one of the elements showing continuity with Roman tradition. From the following century personifications of the River Jordan often appear in depictions of the Baptism of Jesus,[21] and the manuscript Chronography of 354, just a few years older than the sarcophagus and made for another elite Christian, is full of personifications of cities, months and other concepts. The putti in the Chronography also relate closely to those on the sides of the sarcophagus.[22]

Other scenes

The Old Testament scenes depicted were chosen as precursors of Christ's sacrifice in the New Testament, in an early form of typology. Adam and Eve are shown covering their nakedness after the Fall of Man, which created the original sin and hence the need for Christ to be sacrificed for our sins. Adam and Eve themselves made no sacrifices, but behind Eve is a lamb, and beside Adam a sheaf of wheat, referring to the sacrifices of their two sons, Cain and Abel. Just to the right of the middle is Daniel in the lion's den, saved by his faith, and on the left is Abraham about to sacrifice Isaac. Job is seen at the point when he has lost everything, but retains his faith; his wife and a "comforter" look on anxiously. Christians saw these as foreshadowings of the sacrifice of God's only son, Jesus, though the Crucifixion itself, a rare subject up until the 5th century, is not depicted.

The scenes prior to the martyrdoms of Peter and Paul, both common in Early Christian art, show the same avoidance of the climactic moments which were usually chosen in later Christian art. But they demonstrate to the viewer how the heavenly crown could be achieved by ordinary Christians, although the Imperial persecutions were now over. Both scenes also took place in Rome, and this local interest is part of the balance of Christian and traditional Roman gestures that the sarcophagus shows.[23] The reeds behind Paul probably represent the boggy area of the city where Paul's execution was traditionally believed to have happened.[24] Peter's execution was believed to have happened close to his grave, which was within a few feet of the location of the sarcophagus; both executions were believed to have occurred on the same day.

Notes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus. |

- Journal of Early Christian Studies, Leonard Victor Rutgers, The Iconography of the Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus (review of Malbon book) - Volume 1, Number 1, Spring 1993, pp. 94-96; for Janson it is also the "finest Early Christian sarcophagus", and Kitzinger, 26, calls it the "most famous".

- or 1595, see Elsner, p. 86n.

- Reece, 237

- Reece, 240

- Calvesi, Maurizio; Treasures of the Vatican, p.10, Skira, Geneva and New York, 1962

- Kitzinger, 26

- Kitzinger, 22-26, 25 quoted.

- Kitzinger, 26-27, 26 quoted.

- Kitzinger, 28

- Hall, 80

- Hall, pp. 79-80

- Rome the Cosmopolis, p. vii caption 6, Catharine Edwards, Greg Woolf, Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-521-03011-0, ISBN 978-0-521-03011-3

- Lowrie, 90, and J.W. Appell

- Texts, though nb the descriptions of the iconography here are not accurate.

- Elsner, 87

- James Hall, A History of Ideas and Images in Italian Art, p. 80, 1983, John Murray, London, ISBN 0-7195-3971-4. Hellemo, pp. 65-70 discusses the place of the work in the development of the traditio legis subject.

- Janson

- Lowrie, 89 - the cornu, a fist with the index and little finger extended.

- Eduard Syndicus; Early Christian Art; p. 97; Burns & Oates, London, 1962, and see Edwards & Woolf, op & page cit.

- Adventus Domini, p. 100, Geir Hellemo

- G Schiller, Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. I,1971 (English trans from German), Lund Humphries, London, p.133 & figs, ISBN 0-85331-270-2

- Meyer Schapiro, Selected Papers, volume 3, Late Antique, Early Christian and Mediaeval Art, p. 143, 1980, Chatto & Windus, London, ISBN 0-7011-2514-4

- Elsner's main theme

- Lowrie, 89

References

- Elsner, Jaś, in: Catharine Edwards, Greg Woolf. Rome the Cosmopolis, Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-521-03011-0, ISBN 978-0-521-03011-3 google books

- Hall, James. A History of Ideas and Images in Italian Art, p. 80, 1983, John Murray, London, ISBN 0-7195-3971-4

- Janson & Janson, History of Art: The Western Tradition, Horst Woldemar Janson, Anthony F. Janson, 6th edn., Prentice Hall PTR, 2003, ISBN 0-13-182895-9, ISBN 978-0-13-182895-7

- Kitzinger, Ernst, Byzantine art in the making: main lines of stylistic development in Mediterranean art, 3rd-7th century, 1977, Faber & Faber, ISBN 0-571-11154-8 (US: Cambridge UP, 1977)

- Lowrie, Walter. Art in the Early Church, 1947, Read Books reprint 2007, ISBN 1-4067-5291-6, ISBN 978-1-4067-5291-5

- Reece, Richard, in: Henig, Martin (ed), A Handbook of Roman Art, Phaidon, 1983, ISBN 0-7148-2214-0

- Oxford Art Encyclopedia

Further reading

- Elizabeth Struthers Malbon. The Iconography of the Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990

- Weitzmann, Kurt, ed., Age of spirituality : late antique and early Christian art, third to seventh century, no. 386, 1979, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, ISBN 978-0-87099-179-0; full text available online from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries