Srivijaya

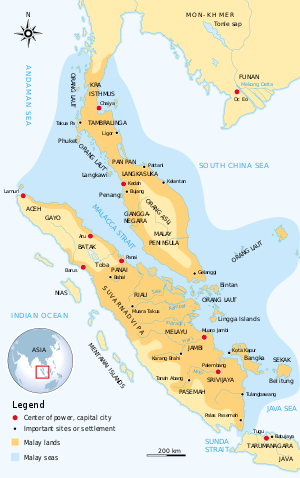

Srivijaya (also written Sri Vijaya or Sriwijaya in Malay or Indonesian)[3]:131 was a Buddhist thalassocratic Indonesian empire based on the island of Sumatra, Indonesia, which influenced much of Southeast Asia.[4] Srivijaya was an important centre for the expansion of Buddhism from the 8th to the 12th century AD. Srivijaya was the first unified kingdom to dominate much of the Indonesian archipelago.[5] The rise of the Srivijayan Empire was parallel to the end of the Malay sea-faring period. Due to its location, this once-powerful state developed complex technology utilizing maritime resources. In addition, its economy became progressively reliant on the booming trade in the region, thus transforming it into a prestige goods-based economy.[6]

Srivijaya Kadatuan Sriwijaya | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 650–1377 | |||||||||||||||

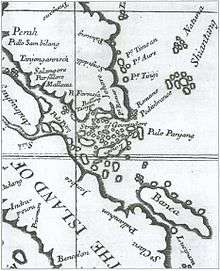

The maximum extent of Srivijaya around the 8th century with a series of Srivijayan expeditions and conquest | |||||||||||||||

| Status | Vassal of the Melayu Kingdom (1183–1377) | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Old Malay and Sanskrit | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Mahayana Buddhism, Vajrayana Buddhism, Hinduism and Animism | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| Maharaja | |||||||||||||||

• Circa 683 | Dapunta Hyang Sri Jayanasa | ||||||||||||||

• Circa 775 | Dharmasetu | ||||||||||||||

• Circa 792 | Samaratungga | ||||||||||||||

• Circa 835 | Balaputra | ||||||||||||||

• Circa 988 | Sri Cudamani Warmadewa | ||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||

• Dapunta Hyang's expedition and expansion (Kedukan Bukit inscription) | 650 | ||||||||||||||

| 1377 | |||||||||||||||

| Currency | Native gold and silver coins | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Indonesia Singapore Malaysia Thailand | ||||||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Malaysia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Prehistoric Malaysia

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Early kingdoms

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Rise of Muslim states

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Colonial era

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

World War II

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Formative era

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Barisan Nasional era

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Pakatan Harapan/Perikatan Nasional era

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Incidents

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The earliest reference to it dates from the 7th century. A Tang Chinese monk, Yijing, wrote that he visited Srivijaya in 671 for six months.[7][8] The earliest known inscription in which the name Srivijaya appears also dates from the 7th century in the Kedukan Bukit inscription found near Palembang, Sumatra, dated 16 June 682.[9] Between the late 7th and early 11th century, Srivijaya rose to become a hegemon in Southeast Asia. It was involved in close interactions, often rivalries, with the neighbouring Java, Kambuja and Champa. Srivijaya's main foreign interest was nurturing lucrative trade agreements with China which lasted from the Tang to the Song dynasty. Srivijaya had religious, cultural and trade links with the Buddhist Pala of Bengal, as well as with the Islamic Caliphate in the Middle East.

The kingdom ceased to exist in the 13th century due to various factors, including the expansion of the rival Javanese Singhasari and Majapahit empires.[4] After Srivijaya fell, it was largely forgotten. It was not until 1918 that French historian George Cœdès, of École française d'Extrême-Orient, formally postulated its existence.[10]

Etymology

Srivijaya is a Sanskrit-derived name: श्रीविजय, Śrīvijaya. Śrī[11] means "fortunate", "prosperous", or "happy" and vijaya[12] means "victorious" or "excellence".[10] Thus, the combined word Srivijaya means "shining victory",[13] "splendid triumph", "prosperous victor", "radiance of excellence" or simply "glorious".

In other languages, Srivijaya is pronounced:

- Burmese: သီရိပစ္စယာ (Thiripyisaya)

- Chinese: 三佛齊 (Sanfoqi).[3]:131

- Javanese: ꦯꦿꦶꦮꦶꦗꦪ (Sriwijaya)

- Khmer: ស្រីវិជ័យ (Srey Vichey)

- Sundanese: ᮞᮢᮤᮝᮤᮏᮚ (Sriwijaya)

- Thai: ศรีวิชัย (RTGS: Siwichai)

Early 20th-century historians that studied the inscriptions of Sumatra and the neighboring islands thought that the term "Srivijaya" referred to a king's name. In 1913, H. Kern was the first epigraphist that identified the name "Srivijaya" written in a 7th century Kota Kapur inscription (discovered in 1892). However, at that time he believed that it referred to a king named "Vijaya", with "Sri" as an honorific title for a king.[14]

The Sundanese manuscript of Carita Parahyangan, composed around the late 16th-century in West Java, vaguely mentioned a princely hero that rose to be a king named Sanjaya that — after he secured his rule in Java — was involved in battle with the Malayu and Keling against their king Sang Sri Wijaya. The term Malayu is a Javanese-Sundanese term referring to the Malay people of Sumatra, while Keling — derived from the historical Kalinga kingdom of Eastern India, refers to people of Indian descent that inhabit the archipelago. Subsequently, after studying local stone inscriptions, manuscripts and Chinese historical accounts, historians concluded that the term "Srivijaya" referred to a polity or kingdom.

Historiography

Little physical evidence of Srivijaya remains.[15] There had been no continuous knowledge of the history of Srivijaya even in Indonesia and Malaysia; its forgotten past has been resurrected by foreign scholars. Contemporary Indonesians, even those from the area of Palembang (around which the kingdom was based), had not heard of Srivijaya until the 1920s when the French scholar, George Cœdès, published his discoveries and interpretations in the Dutch — and Indonesian — language newspapers.[16] Cœdès noted that the Chinese references to "Sanfoqi", previously read as "Sribhoja", and the inscriptions in Old Malay refer to the same empire.[17]

The Srivijayan historiography was acquired, composed and established from two main sources: the Chinese historical accounts and the Southeast Asian stone inscriptions that have been discovered and deciphered in the region. The Buddhist pilgrim Yijing's account is especially important on describing Srivijaya, when he visited the kingdom in 671 for six months. The 7th-century siddhayatra inscriptions discovered in Palembang and Bangka island are also vital primary historical sources. Also, regional accounts that some might be preserved and retold as tales and legends, such as the Legend of the Maharaja of Javaka and the Khmer King also provide a glimpse of the kingdom. Some Indian and Arabic accounts also vaguely describe the riches and fabulous fortune of the king of Zabag.

The historical records of Srivijaya were reconstructed from a number of stone inscriptions, most of them written in Old Malay using Pallava script, such as the Kedukan Bukit, Talang Tuwo, Telaga Batu and Kota Kapur inscriptions.[3]:82–83 Srivijaya became a symbol of early Sumatran importance as a great empire to balance Java's Majapahit in the east. In the 20th century, both empires were referred to by nationalistic intellectuals to argue for an Indonesian identity within an Indonesian state that had existed prior to the colonial state of the Dutch East Indies.[16]

Srivijaya, and by extension Sumatra, had been known by different names to different peoples. The Chinese called it Sanfoqi or Che-li-fo-che (Shilifoshi), and there was an even older kingdom of Kantoli, which could be considered the predecessor of Srivijaya.[18][19] Sanskrit and Pali texts referred to it as Yavades and Javadeh, respectively.[18] The Arabs called it Zabag or Sribuza and the Khmers called it Melayu.[18] While the Javanese called them Suvarnabhumi, Suvarnadvipa or Malayu. This is another reason why the discovery of Srivijaya was so difficult.[18] While some of these names are strongly reminiscent of the name of "Java", there is a distinct possibility that they may have referred to Sumatra instead.[20]

Capital

According to the Kedukan Bukit inscription, dated 605 Saka (683), Srivijaya was first established in the vicinity of today's Palembang, on the banks of Musi River. It mentions that Dapunta Hyang Sri Jayanasa came from Minanga Tamwan. The exact location of Minanga Tamwan is still a subject of discussion. The Palembang theory as the place where Srivijaya was first established was presented by Cœdes and supported by Pierre-Yves Manguin. Soekmono, on the other hand, argues that Palembang was not the capital of Srivijaya and suggests that the Kampar River system in Riau where the Muara Takus temple is located as Minanga Tamwan.[21]

Other than Kedukan Bukit and other Srivijayan inscriptions, immediately to the west of modern Palembang city, a quantity of artefacts have been revealed through archaeological surveys commenced since the 20th century. Artefacts unearthed includes large amount of Chinese ceramics and Indian rouletted ware remains, also the ruins of stupa at the foot of Seguntang Hill. Furthermore, a significant number of Hindu-Buddhist statuary has been recovered from the Musi River basin. These discoveries reinforce the suggestion that Palembang was the center of Srivijaya.[1] Nevertheless, Palembang left little archaeological traces of ancient urban settlement. This is probably because of the nature of Palembang environment — a low-lying plain which frequently flooded by Musi River. Expert suggests that the ancient Palembang settlement was formed as a collection of floating houses made from thatched materials, such as wood, bamboo and straw roof. The 13th century Chinese account confirmed this; in his book Chu-Fan-Chi, Chau-Ju-kua mentioned that "The residents Sanfo-tsi (Srivijaya) live scattered outside the city on the water, within rafts lined with reeds." It was probably only Kadatuan (king's court) and religious structures were built on land, while the people live in floating houses along Musi River.[22]

Palembang and its relevance to the early Malay state suffered a great deal of controversy in terms of its evidence build-up through the archaeological record. Strong historical evidence found in Chinese sources, speaking of city-like settlements as early as 700 AD, and later Arab travelers, who visited the region during the 10th and 11th centuries, held written proof, naming the kingdom of Srivijaya in their context. As far as early state-like polities in Malay archipelago, the geographical location of modern Palembang was a possible candidate for the 1st millennium kingdom settlement like Srivijaya as it is the best described and most secure in historical context, its prestige was apparent in wealth and urban characteristics, and the most unique, which no other 1st millennium kingdom held, was its location in junction to three major rivers, the Musi, the Komering, and the Ogan. The historical evidence was contrasted in 1975 with publications by Bennet Bronson and Jan Wisseman. Findings at certain major excavation sites, such as Geding Suro, Penyaringan Air Bersih, Sarang Wati, and Bukit Seguntang, conducted in the region played major roles in the negative evidence of the 1st millennium kingdom in the same region. It was noted that the region contained no locatable settlements earlier than the middle of the second millennium.

Lack of evidence of southern settlements in the archaeological record comes from the disinterest in the archeologist and the unclear physical visibility of the settlement themselves. Archeology of the 1920s and 1930s focused more on art and epigraphy found in the regions. Some northern urban settlements were sited due to some overlap in fitting the sinocentric model of city-state urban centers. An approach to differentiate between urban settlements in the southern regions from the northern ones of Southeast Asia was initiated by a proposition for an alternative model. Excavations showed failed signs of a complex urban center under the lens of a sinocentric model, leading to parameters of a new proposed model. Parameters for such a model of a city-like settlement included isolation in relevance to its hinterland. No hinterland creates for low archaeological visibility. The settlement must also have access to both easy transportation and major interregional trade routes, crucial in a region with few resources. Access to the former and later played a major role in the creation of an extreme economic surplus in the absence of an exploited hinterland. The urban center must be able to organize politically without the need for ceremonial foci such as temples, monuments and inscriptions. Lastly, habitations must be impermanent, being highly probable in the region Palembang and of southern Southeast Asia. Such a model was proposed to challenge city concepts of ancient urban centers in Southeast Asia and basic postulates themselves such as regions found in the South, like Palembang, based their achievements in correlation with urbanization.[23]

Due to the contradicting pattern found in southern regions, like Palembang, in 1977 Bennet Bronson developed a speculative model for a better understanding of the Sumatran coastal region, such as insular and peninsular Malaysia, the Philippines, and western Indonesia. Its main focus was the relationship of political, economic and geographical systems. The general political and economic pattern of the region seems irrelevant to other parts of the world of their time, but in correlation with their maritime trade network, it produced high levels of socio-economic complexity. He concluded, from his earlier publications in 1974 that state development in this region developed much differently than the rest of early Southeast Asia. Bronson's model was based on the dendritic patterns of a drainage basin where its opening leads out to sea. Being that historical evidence places the capital in Palembang, and in junction of three rivers, the Musi, the Komering, and the Ogan, such model can be applied. For the system to function appropriately, several constraints are required. The inability for terrestrial transportation results in movements of all goods through water routes, lining up economical patterns with the dendritic patterns formed by the streams. The second being the overseas center is economically superior to the ports found at the mouth of the rivers, having a higher population and a more productive and technologically advanced economy. Lastly, constraints on the land work against and do not developments of urban settlements.[24]

An aerial photograph taken in 1984 near Palembang (in what is now Sriwijaya Kingdom Archaeological Park) revealed the remnants of ancient man-made canals, moats, ponds, and artificial islands, suggesting the location of Srivijaya's urban centre. Several artefacts such as fragments of inscriptions, Buddhist statues, beads, pottery and Chinese ceramics were found, confirming that the area had, at one time, dense human habitation.[25] By 1993, Pierre-Yves Manguin had shown that the centre of Srivijaya was along the Musi River between Bukit Seguntang and Sabokingking (situated in what is now Palembang, South Sumatra, Indonesia).[10] Palembang is called in Chinese: 巨港; pinyin: Jù gǎng; lit.: 'Giant Harbour', this is probably a testament of its history as once a great port.

However, in 2013, archaeological research led by the University of Indonesia discovered several religious and habitation sites at Muaro Jambi, suggesting that the initial centre of Srivijaya was located in Muaro Jambi Regency, Jambi on the Batang Hari River, rather than on the originally-proposed Musi river.[26] The archaeological site includes eight excavated temple sanctuaries and covers about 12 square kilometers, stretches 7.5 kilometers along the Batang Hari River, 80 menapos or mounds of temple ruins, are not yet restored.[27][28] The Muaro Jambi archaeological site was Mahayana-Vajrayana Buddhist in nature, which suggests that the site served as the Buddhist learning center, connected to the 10th century famous Buddhist scholar Suvarṇadvipi Dharmakīrti. Chinese sources also mentioned that Srivijaya hosts thousands of Buddhist monks.

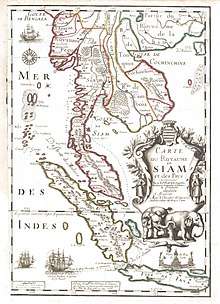

Another theory suggests that Dapunta Hyang came from the east coast of the Malay Peninsula, and that the Chaiya District in Surat Thani Province, Thailand, was the centre of Srivijaya.[29] The Srivijayan Period is referred to as the time when Srivijaya ruled over present-day southern Thailand. In the region of Chaiya, there is clear evidence of Srivijayan influence seen in artwork inspired by Mahayana Buddhism. Because of the large amount of remains, such as the Ligor stele, found in this region, some scholars attempted to prove Chaiya as the capital rather than Palembang.[30] This period was also a time for art. The Buddhist art of the Srivijayan Kingdom was believed to have borrowed from Indian styles like that of the Dvaravati school of art.[31] The city of Chaiya's name may be derived from the Malay name "Cahaya" which means "light" or "radiance". However, some scholars believe that Chaiya probably comes from Sri Vijaya. It was a regional capital in the Srivijaya empire. Some Thai historians argue it was the capital of Srivijaya itself,[32] but this is generally discounted.

.jpg)

In the second half of the eighth century, the capital of Srivijayan Mandala seems to be relocated and reestablished in Central Java, in the splendid court of Medang Mataram located somewhere in fertile Kedu and Kewu Plain, in the same location of the majestic Borobudur, Manjusrigrha and Prambanan monuments. This unique period is known as the Srivijayan episode in Central Java, when the monarch of Sailendras rose to become the Maharaja of Srivijaya. By that time, Srivijayan Mandala seems to be consists of the federation or an alliance of city-states, spanned from Java to Sumatra and Malay Peninsula, connected with trade connection cemented with political allegiance. By that time Srivijayan trading centres remain in Palembang, and to further extent also includes ports of Jambi, Kedah and Chaiya; while its political, religious and ceremonial center was established in Central Java.

History

Formation and growth

Siddhayatra

Around the year 500, the roots of the Srivijayan empire began to develop around present-day Palembang, Sumatra. The Kedukan Bukit inscription (683), discovered on the banks of the Tatang River near the Karanganyar site, states that the empire of Srivijaya was founded by Dapunta Hyang Sri Jayanasa and his retinue. He had embarked on a sacred siddhayatra[33] journey and led 20,000 troops and 312 people in boats with 1,312 foot soldiers from Minanga Tamwan to Jambi and Palembang.

From the Sanskrit inscriptions, it is notable that Dapunta Hyang Sri Jayanasa launched a maritime conquest in 684 with 20,000 men in the siddhayatra journey to acquire wealth, power, and 'magical powers'.[34] Under the leadership of Dapunta Hyang Sri Jayanasa, the Melayu Kingdom became the first kingdom to be integrated into Srivijaya. This possibly occurred in the 680s. Melayu, also known as Jambi, was rich in gold and held in high esteem at the time. Srivijaya recognised that the submission of Melayu would increase its own prestige.[35]

The empire was organised in three main zones: the estuarine capital region centred on Palembang, the Musi River basin which served as a hinterland, and rival estuarine areas capable of forming rival power centres. The areas upstream of the Musi River were rich in various commodities valuable to Chinese traders.[36] The capital was administered directly by the ruler, while the hinterland remained under local datus or tribal chiefs, who were organised into a network of alliances with the Srivijaya maharaja or king. Force was the dominant element in the empire's relations with rival river systems such as the Batang Hari River, centred in Jambi.

The Telaga Batu inscription, discovered in Sabokingking, eastern Palembang, is also a siddhayatra inscription, from the 7th century. This inscription was very likely used in a ceremonial sumpah (allegiance ritual). The top of the stone is adorned with seven nāga heads, and on the lower portion there is a type of water spout to channel liquid that was likely poured over the stone during a ritual. The ritual included a curse upon those who commit treason against Kadatuan Srivijaya.

The Talang Tuwo inscription is also a siddhayatra inscription. Discovered in Bukit Seguntang, western Palembang, this inscription tells about the establishment of the bountiful Śrīksetra garden endowed by King Jayanasa of Srivijaya for the well-being of all creatures.[3]:82–83 It is likely that the Bukit Seguntang site was the location of the Śrīksetra garden.

Regional conquests

According to the Kota Kapur inscription discovered on Bangka Island, the empire conquered most of southern Sumatra and the neighbouring island of Bangka as far as Palas Pasemah in Lampung. Also, according to the inscriptions, Dapunta Hyang Sri Jayanasa launched a military campaign against Java in the late 7th century, a period which coincided with the decline of Tarumanagara in West Java and the Kalingga in Central Java. The empire thus grew to control trade on the Strait of Malacca, the Sunda Strait, the South China Sea, the Java Sea and the Karimata Strait.

Chinese records dating to the late 7th century mention two Sumatran kingdoms and three other kingdoms on Java as being part of Srivijaya. By the end of the 8th century, many western Javanese kingdoms, such as Tarumanagara and Kalingga, were within the Srivijayan sphere of influence.

Golden age

The 7th-century Sojomerto inscription mentioned that an Old Malay-speaking Shivaist family led by Dapunta Selendra had established themselves in the Batang area of the northern coast of Central Java. He was possibly the progenitor of the Sailendra family. By the early 8th century, an influential Buddhist family related to Srivijaya dominated Central Java.[37] The family was the Sailendras,[38] of Javanese origin.[39] The ruling lineage of Srivijaya intermarried with the Sailendras of Central Java.

Conquest of Malay Peninsula

During the same century, Langkasuka on the Malay Peninsula became part of Srivijaya.[40] Soon after this, Pan Pan and Tambralinga, north of Langkasuka, came under Srivijayan influence. These kingdoms on the peninsula were major trading nations that transported goods across the peninsula's isthmus.

The Ligor inscription in Vat Sema Muang says that Maharaja Dharmasetu of Srivijaya ordered the construction of three sanctuaries dedicated to the Bodhisattvas Padmapani, Vajrapani, and Buddha in the northern Malay Peninsula.[41] The inscription further stated that the Dharmasetu was the head of the Sailendras of Java. This is the first known instance of a relationship between Srivijaya and the Sailendra. With the expansion into Java and the Malay Peninsula, Srivijaya controlled two major trade choke points in Southeast Asia: the Malacca and Sunda straits. Some Srivijayan temple ruins are observable in Thailand and Cambodia.

At some point in the late 7th century, Cham ports in eastern Indochina started to attract traders. This diverted the flow of trade from Srivijaya. To stop this, Maharaja Dharmasetu launched raids against the coastal cities of Indochina. The city of Indrapura by the Mekong was temporarily controlled from Palembang in the early 8th century.[38] The Srivijayans continued to dominate areas around present-day Cambodia until the Khmer King Jayavarman II, the founder of the Khmer Empire dynasty, severed the Srivijayan link later in the same century.[42] In 851 an Arabic merchant named Sulaimaan recorded an event about Javanese Sailendras staging a surprise attack on the Khmers by approaching the capital from the river, after a sea crossing from Java. The young king of Khmer was later punished by the Maharaja, and subsequently the kingdom became a vassal of Sailendra dynasty.[43]:35 In 916 CE, a Javanese kingdom invaded Khmer Empire, using 1000 "medium-sized" vessels, which results in Javanese victory. The head of Khmer's king then brought to Java.[44]:187–189

Srivijayan rule in Central Java

The Sailendras of Java established and nurtured a dynastic alliance with the Sumatran Srivijayan lineage, and then further established their rule and authority in the Medang Mataram Kingdom of Central Java.

In Java, Dharanindra's successor was Samaragrawira (r. 800—819), mentioned in the Nalanda inscription (dated 860) as the father of Balaputradewa, and the son of Śailendravamsatilaka (the jewel of the Śailendra family) with stylised name Śrīviravairimathana (the slayer of a heroic enemy), which refers to Dharanindra.[3]:92 Unlike his predecessor, the expansive and warlike Dharanindra, Samaragrawira seems to have been a pacifist, enjoying the peaceful prosperity of interior Java in Kedu Plain and being more interested in completing the Borobudur project. He appointed Khmer Prince Jayavarman as the governor of Indrapura in the Mekong delta under Sailendran rule. This decision was later proven to be a mistake, as Jayavarman revolted, moved his capital further inland north from Tonle Sap to Mahendraparvata, severed the link to Srivijaya and proclaimed Cambodian independence from Java in 802. Samaragrawira was mentioned as the king of Java that married Tārā, daughter of Dharmasetu.[3]:108 He was mentioned as his other name Rakai Warak in Mantyasih inscription.

Earlier historians, such as N. J. Krom and Cœdes, tend to equate Samaragrawira and Samaratungga as the same person.[3]:92 However, later historians such as Slamet Muljana equate Samaratungga with Rakai Garung, mentioned in the Mantyasih inscription as the fifth monarch of the Mataram kingdom. This would mean that Samaratungga was the successor of Samaragrawira.

Dewi Tara, the daughter of Dharmasetu, married Samaratunga, a member of the Sailendra family who assumed the throne of Srivijaya around 792.[45] By the 8th century, the Srivijayan court was virtually located in Java, as the Sailendras monarch rose to become the Maharaja of Srivijaya.

After Dharmasetu, Samaratungga became the next Maharaja of Srivijaya. He reigned as ruler from 792 to 835. Unlike the expansionist Dharmasetu, Samaratungga did not indulge in military expansion but preferred to strengthen the Srivijayan hold of Java. He personally oversaw the construction of the grand monument of Borobudur; a massive stone mandala, which was completed in 825, during his reign.[46] According to Cœdès, "In the second half of the ninth century Java and Sumatra were united under the rule of a Sailendra reigning in Java... its center at Palembang."[3]:92 Samaratungga, just like Samaragrawira, seems to have been deeply influenced by peaceful Mahayana Buddhist beliefs and strove to become a peaceful and benevolent ruler. His successor was Princess Pramodhawardhani who was betrothed to Shivaite Rakai Pikatan, son of the influential Rakai Patapan, a landlord in Central Java. The political move that seems as an effort to secure peace and Sailendran rule on Java by reconciling the Mahayana Buddhist with Shivaist Hindus.

Return to Palembang

Prince Balaputra, however, opposed the rule of Pikatan and Pramodhawardhani in Central Java. The relations between Balaputra and Pramodhawardhani are interpreted differently by some historians. An older theory according to Bosch and De Casparis holds that Balaputra was the son of Samaratungga, which means he was the younger brother of Pramodhawardhani. Later historians such as Muljana, on the other hand, argued that Balaputra was the son of Samaragrawira and the younger brother of Samaratungga, which means he was the uncle of Pramodhawardhani.[47]

It is not known whether Balaputra was expelled from Central Java because of a succession dispute with Pikatan, or he already ruled in Suvarnadvipa (Sumatra). Either way, it seems that Balaputra eventually ruled the Sumatran branch of Sailendra dynasty and enthroned in Srivijayan capital of Palembang. Historians argued that this was because Balaputra's mother Tara, the queen consort of King Samaragrawira, was the princess of Srivijaya, making Balaputra the heir of the Srivijayan throne. Balaputra the Maharaja of Srivijaya later stated his claim as the rightful heir of the Sailendra dynasty from Java, as proclaimed in the Nalanda inscription dated 860.[3]:108

After a trade disruption at Canton between 820 and 850, the ruler of Jambi (Melayu Kingdom) was able to assert enough independence to send missions to China in 853 and 871. The Melayu kingdom's independence coincided with the troubled times when the Sailendran Balaputradewa was expelled from Java and, later, he seized the throne of Srivijaya. The new maharaja was able to dispatch a tributary mission to China by 902. Two years after that, the expiring Tang Dynasty conferred a title on a Srivijayan envoy.

In the first half of the 10th century, between the fall of Tang Dynasty and the rise of Song, there was brisk trading between the overseas world with the Fujian kingdom of Min and the rich Guangdong kingdom of Nan Han. Srivijaya undoubtedly benefited from this. Sometime around 903, the Muslim writer Ibn Rustah was so impressed with the wealth of the Srivijayan ruler that he declared that one would not hear of a king who was richer, stronger or had more revenue. The main urban centres of Srivijaya were then at Palembang (especially the Karanganyar site near Bukit Seguntang area), Muara Jambi and Kedah.

Srivijayan exploration

The core of the Srivijayan realm was concentrated in and around the straits of Malacca and Sunda and in Sumatra, the Malay Peninsula and Western Java. However, between the 9th and the 12th centuries, the influence of Srivijaya seems to have extended far beyond the core. Srivijayan navigators, sailors and traders seem to have engaged in extensive trade and exploration, which reached coastal Borneo,[48] the Philippines archipelago, Eastern Indonesia, coastal Indochina, the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean as far as Madagascar.[49]

The migration to Madagascar accelerated in the 9th century when Srivijaya controlled much of the maritime trade in the Indian Ocean.[50] The migration to Madagascar was estimated to have taken place 1,200 years ago around 830 CE. According to an extensive new mitochondrial DNA study, native Malagasy people today can likely trace their heritage back to 30 founding mothers who sailed from Indonesia 1,200 years ago. Malagasy contains loan words from Sanskrit, with all the local linguistic modifications via Javanese or Malay, hinting that Madagascar may have been colonised by settlers from Srivijaya.[51]

The influence of the empire reached Manila by the 10th century. A kingdom under its sphere of influence had already been established there.[52][53] The discovery of a golden statue in Agusan del Sur and a golden Kinnara from Butuan, Northeastern Mindanao, in the Philippines suggests an ancient link between ancient Philippines and the Srivijayan empire,[54] since Tara and Kinnara are important figures or deities in Mahayana Buddhist beliefs. The Mahayana-Vajrayana Buddhist religious commonality suggests that ancient Philippines acquired their Mahayana-Vajrayana beliefs from Srivijayan influence in Sumatra.[55] Although the gold industries is Butuan far exceeded those in Srivijaya or any related polity in Sumatra.[56]

The 10th-century Arab account Ajayeb al-Hind (Marvels of India) tells of an invasion in Africa, probably by Malay people of Srivijaya, in 945–946. They arrived on the coast of Tanganyika and Mozambique with 1,000 ships and boats and attempted to capture the citadel of Qanbaloh, though they eventually failed. The reason for the attack was to acquire African commodities coveted by the Asian market, especially China, such as ivory, tortoiseshell, panther fur, and ambergris, and also to extract black slaves from Bantu tribes (called Zeng or Zenj by Malay, Jenggi by Javanese); these were perceived as physically strong and thus would make good slaves.[57]

By the 12th century, the kingdom included parts of Sumatra, the Malay Peninsula, Western Java, and parts of Borneo. It also had influence over specific parts of the Philippines, most notably the Sulu Archipelago and the Visayas islands. It is believed by some historians that the name 'Visayas' is derived from the empire.[58][49]

War against Java

In the 10th century, the rivalry between Sumatran Srivijaya and the Javanese Medang kingdom became more intense and hostile. The animosity was probably caused by Srivijaya's effort to reclaim the Sailendra lands in Java or by Medang's aspiration to challenge Srivijaya domination in the region. In East Java, the Anjukladang inscription dated from 937 mentions an infiltration attack from Malayu — which refers to a Srivijayan attack upon the Medang Kingdom of East Java. The villagers of Anjuk Ladang were awarded for their service and merit in assisting the king's army, under the leadership of Mpu Sindok, in repelling invading Malayu (Sumatra) forces; subsequently, a jayastambha (victory monument) was erected in their honor.

In 990, King Dharmawangsa of Java launched a naval invasion against Srivijaya and attempted to capture the capital Palembang. The news of the Javanese invasion of Srivijaya was recorded in Chinese Song period sources. In 988, a Srivijayan envoy was sent to the Chinese court in Guangzhou. After sojourning for about two years in China, the envoy learned that his country had been attacked by She-po (Java) which made him unable to return home. In 992 the envoy from She-po (Java) arrived in the Chinese court and explaining that their country was involved in continuous war with San-fo-qi (Srivijaya). In 999 the Srivijayan envoy sailed from China to Champa in an attempt to return home, however, he received no news about the condition of his country. The Srivijayan envoy then sailed back to China and appealed to the Chinese Emperor for the protection of Srivijaya against Javanese invaders.[59]:229

Dharmawangsa's invasion led the Maharaja of Srivijaya, Sri Cudamani Warmadewa, to seek protection from China. Warmadewa was known as an able and astute ruler, with shrewd diplomatic skills. In the midst of the crisis brought by the Javanese invasion, he secured Chinese political support by appeasing the Chinese Emperor. In 1003, a Song historical record reported that the envoy of San-fo-qi was dispatched by the king Shi-li-zhu-luo-wu-ni-fo-ma-tiao-hua (Sri Cudamani Warmadewa). The Srivijayan envoy told the Chinese court that in their country a Buddhist temple had been erected to pray for the long life of Chinese Emperor, and asked the emperor to give the name and the bell for this temple which was built in his honor. Rejoiced, the Chinese Emperor named the temple Ch'eng-t'en-wan-shou ('ten thousand years of receiving blessing from heaven, which is China) and a bell was immediately cast and sent to Srivijaya to be installed in the temple.[59]:6

In 1006, Srivijaya's alliance proved its resilience by successfully repelling the Javanese invasion. The Javanese invasion was ultimately unsuccessful. This attack opened the eyes of Srivijayan Maharaja to the dangerousness of the Javanese Medang Kingdom, so he patiently laid a plan to destroy his Javanese nemesis. In retaliation, Srivijaya assisted Haji (king) Wurawari of Lwaram to revolt, which led to the attack and destruction of the Medang palace. This sudden and unexpected attack took place during the wedding ceremony of Dharmawangsa's daughter, which left the court unprepared and shocked. With the death of Dharmawangsa and the fall of the Medang capital, Srivijaya contributed to the collapse of Medang kingdom, leaving Eastern Java in further unrest, violence and, ultimately, desolation for several years to come.[3]:130,132,141,144

Decline

Chola invasion

The contributory factors in the decline of Srivijaya were foreign piracy and raids that disrupted trade and security in the region. Attracted to the wealth of Srivijaya, Rajendra Chola, the Chola king from Tamil Nadu in South India, launched naval raids on ports of Srivijaya and conquered Kadaram (modern Kedah) from Srivijaya in 1025.[3]:142–143 The Cholas are known to have benefitted from both piracy and foreign trade. At times, the Chola seafaring led to outright plunder and conquest as far as Southeast Asia.[60] An inscription of King Rajendra states that he had captured the King of Kadaram, Sangrama Vijayatunggavarman, son of Mara Vijayatunggavarman, and plundered many treasures including the Vidhyadara-torana, the jewelled 'war gate' of Srivijaya adorned with great splendour.

According to the 15th-century Malay annals Sejarah Melayu, Rajendra Chola I after the successful naval raid in 1025 married Onang Kiu, the daughter of Vijayottunggavarman.[61][62] This invasion forced Srivijaya to make peace with the Javanese kingdom of Kahuripan. The peace deal was brokered by the exiled daughter of Vijayottunggavarman, who managed to escape the destruction of Palembang, and came to the court of King Airlangga in East Java. She also became the queen consort of Airlangga named Dharmaprasadottungadevi and, in 1035, Airlangga constructed a Buddhist monastery named Srivijayasrama dedicated to his queen consort.[63]:163

The Cholas continued a series of raids and conquests of parts of Sumatra and Malay Peninsula for the next 20 years. The expedition of Rajendra Chola I had such a lasting impression on the Malay people of the period that his name is even mentioned (in the corrupted form as Raja Chulan) in the medieval Malay chronicle the Sejarah Melayu (Malay Annals).[61][64][65][66] Even today the Chola rule is remembered in Malaysia as many Malaysian princes have names ending with Cholan or Chulan, one such was the Raja of Perak called Raja Chulan.[67][68][69]

Rajendra Chola's overseas expeditions against Srivijaya were unique in India's history and its otherwise peaceful relations with the states of Southeast Asia. The reasons for the naval expeditions are uncertain as the sources are silent about its exact causes. Nilakanta Sastri suggests that the attacks were probably caused by Srivijaya's attempts to throw obstacles in the way of the Chola trade with the East or, more probably, a simple desire on the part of Rajendra Chola to extend his military victories to the well known countries to gain prestige.[59] It gravely weakened the Srivijayan hegemony and enabled the formation of regional kingdoms like Kediri, which were based on intensive agriculture rather than coastal and long-distance trade. With the passing of time, the regional trading center shifted from the old Srivijayan capital of Palembang to another trade centre on the island of Sumatra, Jambi, which was the centre of Malayu.[69]

Under the Cholas

The Chola control over Srivijaya under Rajendra Chola I lasted two decades until 1045 AD. According to one theory proposed by Sri Lankan historian Paranavitana, Rajendra Chola I was murdered in 1044 AD, during his visit to Srivijaya by Purandara, on the order of Samara Vijayatunggavarman, Sangrama Vijayatunggavarman's brother. According to this theory, Samara launched a massive annihilation against Chola and claimed the Srivijaya throne in 1045. Samara sent his cousin and son-in-law, Mahendra, with his army to help Vijayabahu I to defeat the Cholas and regain the throne. Samara's name was mentioned by Mahinda VI of Polonnaruwa in the Madigiriya inscription and Bolanda inscription.[70] On the contrary, according to South Indian epigraphs and records, Rajendra Chola I died in Brahmadesam, now a part of the North Arcot district in Tamil Nadu, India. This information is recorded in an inscription of his son, Rajadhiraja Chola I, which states that Rajendra Chola's queen Viramadeviyar committed sati upon Rajendra's death and her remains were interred in the same tomb as Rajendra Chola I in Brahmadesam. It adds that the queen's brother, who was a general in Rajendra's army, set up a watershed at the same place in memory of his sister.[71]

There is also evidence to suggest that Kulottunga Chola, the maternal grandson of emperor Rajendra Chola I, in his youth (1063) was in Sri Vijaya,[3]:148 restoring order and maintaining Chola influence in that area. Virarajendra Chola states in his inscription, dated in the 7th year of his reign, that he conquered Kadaram (Kedah) and gave it back to its king who came and worshiped his feet.[72] These expeditions were led by Kulottunga to help the Sailendra king who had sought the help of Virarajendra Chola.[73] An inscription of Canton mentions Ti-hua-kialo as the ruler of Sri Vijaya. According to historians, this ruler is the same as the Chola ruler Ti-hua-kialo (identified with Kulottunga) mentioned in the Song annals and who sent an embassy to China. According to Tan Yeok Song, the editor of the Sri Vijayan inscription of Canton, Kulottunga stayed in Kadaram (Kedah) after the naval expedition of 1067 AD and reinstalled its king before returning to South India and ascending the throne.[74]

Internal and external rivalries

Between 1079 and 1088, Chinese records show that Srivijaya sent ambassadors from Jambi and Palembang.[75] In 1079 in particular, an ambassador from Jambi and Palembang each visited China. Jambi sent two more ambassadors to China in 1082 and 1088.[75] That would suggest that the centre of Srivijaya frequently shifted between the two major cities during that period.[75] The Chola expeditions as well as the changing trade routes weakened Palembang, allowing Jambi to take the leadership of Srivijaya from the 11th century onwards.[76]

By the 12th century, a new dynasty called Mauli rose as the paramount of Srivijaya. The earliest reference to the new dynasty was found in the Grahi inscription from 1183 discovered in Chaiya (Grahi), Southern Thailand Malay Peninsula. The inscription bears the order of Maharaja Srimat Trailokyaraja Maulibhusana Warmadewa to the bhupati (regent) of Grahi named Mahasenapati Galanai to make a statue of Buddha weighing 1 bhara 2 tula with a value of 10 gold tamlin. The artist responsible for the creation of the statue is Mraten Sri Nano.

According to the Chinese Song Dynasty book Zhu Fan Zhi,[77] written around 1225 by Zhao Rugua, the two most powerful and richest kingdoms in the Southeast Asian archipelago were Srivijaya and Java (Kediri), with the western part (Sumatra, the Malay peninsula, and western Java/Sunda) under Srivijaya's rule and the eastern part was under Kediri's domination. It says that the people in Java followed two kinds of religions, Buddhism and the religion of Brahmins (Hinduism), while the people of Srivijaya followed Buddhism. The book describes the people of Java as being brave, short-tempered and willing to fight. It also notes that their favourite pastimes were cockfighting and pig fighting. The coins used as currency were made from a mixture of copper, silver and tin.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Thailand |

|

|

Legendary Suvarnabhumi Central Thailand Dvaravati Lavo Supannabhum Northern Thailand Singhanavati Ngoenyang Hariphunchai Lanna Southern Thailand Pan Pan Raktamaritika Langkasuka Srivijaya Tambralinga Nakhon Si Thammarat Sultanate of Pattani Kedah Sultanate Malacca Sultanate Satun Reman |

| History |

|

Regional history |

|

Related topics

|

|

|

Zhu fan zhi also states that Java was ruled by a maharaja and included the following "dependencies": Pai-hua-yuan (Pacitan), Ma-tung (Medang), Ta-pen (Tumapel, now Malang), Hi-ning (Dieng), Jung-ya-lu (Hujung Galuh, now Surabaya), Tung-ki (Jenggi, West Papua), Ta-kang (Sumba), Huang-ma-chu (Southwest Papua), Ma-li (Bali), Kulun (Gurun, identified as Gorong or Sorong in West Papua or an island in Nusa Tenggara), Tan-jung-wu-lo (Tanjungpura in Borneo), Ti-wu (Timor), Pingya-i (Banggai in Sulawesi) and Wu-nu-ku (Maluku).[3]:186–187 Additionally, Zhao Rugua said that Srivijaya "was still a great power at the beginning of the thirteenth century" with 15 colonies:[78] Pong-fong (Pahang), Tong-ya-nong (Terengganu), Ling-ya-si-kia (Langkasuka), Kilan-tan (Kelantan), Fo-lo-an (Dungun, eastern part of Malay Peninsula, a town within state of Terengganu), Ji-lo-t'ing (Cherating), Ts'ien-mai (Semawe, Malay Peninsula), Pa-t'a (Sungai Paka, located in Terengganu of Malay Peninsula), Tan-ma-ling (Tambralinga, Ligor or Nakhon Si Thammarat, South Thailand), Kia-lo-hi (Grahi, (Krabi) northern part of Malay peninsula), Pa-lin-fong (Palembang), Sin-t'o (Sunda), Lan-wu-li (Lamuri at Aceh), Kien-pi (Jambi) and Si-lan (Cambodia or Ceylon (?)).[3]:183–184[79][80]

Srivijaya remained a formidable sea power until the 13th century.[4] According to Cœdès, at the end of the 13th century, the empire "had ceased to exist... caused by the simultaneous pressure on its two flanks of Siam and Java."[3]:204,243

Javanese pressure

By the 13th century, the Singhasari empire, the successor state of Kediri in Java, rose as a regional hegemon in maritime Southeast Asia. In 1275, the ambitious and able king Kertanegara, the fifth monarch of Singhasari who had been reigning since 1254, launched a naval campaign northward towards the remains of the Srivijayan mandala.[3]:198 The strongest of these Malay kingdoms was Jambi, which captured the Srivijaya capital in 1088, then the Dharmasraya kingdom, and the Temasek kingdom of Singapore, and then remaining territories. In 1288, Kertanegara's forces conquered most of the Melayu states, including Palembang, Jambi and much of Srivijaya, during the Pamalayu expedition. The Padang Roco Inscription was discovered in 1911 near the source of the Batang Hari river.[81] The 1286 inscription states that under the order of king Kertanegara of Singhasari, a statue of Amoghapasa Lokeshvara was transported from Bhumijawa (Java) to Suvarnabhumi (Sumatra) to be erected at Dharmasraya. This gift made the people of Suvarnabhumi rejoice, especially their king Tribhuwanaraja.

In 1293, the Majapahit empire, the successor state of Singhasari, ruled much of Sumatra. Prince Adityawarman was given power over Sumatera in 1347 by Tribhuwana Wijayatunggadewi, the third monarch of Majapahit. A rebellion broke out in 1377 and was quashed by Majapahit but it left the area of southern Sumatera in chaos and desolation.

In the following years, sedimentation on the Musi river estuary cut the kingdom's capital off from direct sea access. This strategic disadvantage crippled trade in the kingdom's capital. As the decline continued, Islam made its way to the Aceh region of Sumatra, spreading through contacts with Arab and Indian traders. By the late 13th century, the kingdom of Pasai, in northern Sumatra, converted to Islam. At the same time, Srivijayan lands in the Malay Peninsula (now Southern Thailand) were briefly a tributary state of the Khmer empire and later the Sukhothai kingdom. The last inscription on which a crown prince, Ananggavarman, son of Adityawarman, is mentioned, dates from 1374.

Last revival efforts

After decades of Javanese domination, there were several last efforts made by Sumatran rulers to revive the old prestige and fortune of Malay-Srivijayan Mandala. Several attempts to revive Srivijaya were made by the fleeing princes of Srivijaya. According to the Malay Annals, a new ruler named Sang Sapurba was promoted as the new paramount of Srivijayan mandala. It was said that after his accession to Seguntang Hill with his two younger brothers, Sang Sapurba entered into a sacred covenant with Demang Lebar Daun, the native ruler of Palembang.[82] The newly installed sovereign afterwards descended from the hill of Seguntang into the great plain of the Musi river, where he married Wan Sendari, the daughter of the local chief, Demang Lebar Daun. Sang Sapurba was said to have reigned in Minangkabau lands.

According to Visayan legends, in the 1200s, there was a resistance movement of Srivijayan datus aimed against the encroaching powers of the Hindu Chola and Majapahit empires. The datus migrated to and organized their resistance movement from the Visayas islands of the Philippines, which was named after their Srivijayan homeland.[83] Ten Datus, led by Datu Puti, established a rump state of Srivijaya, called Madja-as, in the Visayas islands.[84] This rump state waged war against the Chola empire and Majapahit and also raided China,[85] before they were eventually assimilated into a Spanish empire that expanded to the Philippines from Mexico.

In 1324, a Srivijaya prince, Sri Maharaja Sang Utama Parameswara Batara Sri Tribuwana (Sang Nila Utama), founded the Kingdom of Singapura (Temasek). According to tradition, he was related to Sang Sapurba. He maintained control over Temasek for 48 years. He was recognised as ruler over Temasek by an envoy of the Chinese Emperor sometime around 1366. He was succeeded by his son Paduka Sri Pekerma Wira Diraja (1372–1386) and grandson, Paduka Seri Rana Wira Kerma (1386–1399). In 1401, the last ruler, Paduka Sri Maharaja Parameswara, was expelled from Temasek by forces from Majapahit or Ayutthaya. He later headed north and founded the Sultanate of Malacca in 1402.[3]:245–246 The Sultanate of Malacca succeeded the Srivijaya Empire as a Malay political entity in the archipelago.[86][87]

Government and economy

Political administration

The 7th century Telaga Batu inscription, discovered in Sabokingking, Palembang, testifies to the complexity and stratified titles of the Srivijayan state officials. These titles are mentioned: rājaputra (princes, lit: sons of king), kumārāmātya (ministers), bhūpati (regional rulers), senāpati (generals), nāyaka (local community leaders), pratyaya (nobles), hāji pratyaya (lesser kings), dandanayaka (judges), tuhā an vatak (workers inspectors), vuruh (workers), addhyāksi nījavarna (lower supervisors), vāsīkarana (blacksmiths/weapon makers), cātabhata (soldiers), adhikarana (officials), kāyastha (store workers), sthāpaka (artisans), puhāvam (ship captains), vaniyāga (traders), marsī hāji (king's servants), hulun hāji (king's slaves).[88]

During its formation, the empire was organised in three main zones — the estuarine capital region centred on Palembang, the Musi River basin which served as hinterland and source of valuable goods, and rival estuarine areas capable of forming rival power centres. These rival estuarine areas, through raids and conquests, were held under Srivijayan power, such as the Batanghari estuarine (Malayu in Jambi). Several strategic ports also included places like Bangka Island (Kota Kapur), ports and kingdoms in Java (highly possible Tarumanagara and Kalingga), Kedah and Chaiya in Malay peninsula, and Lamuri and Pannai in northern Sumatra. There are also reports mentioning the Java-Srivijayan raids on Southern Cambodia (Mekong estuarine) and ports of Champa.

After its expansion to the neighbouring states, the Srivijayan empire was formed as a collection of several Kadatuans (local principalities), which swore allegiance to the central ruling powerful Kadatuan ruled by the Srivijayan Maharaja. The political relations and system relating to its realms is described as a mandala model, typical of that of classical Southeast Asian Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms. It could be described as federation of kingdoms or vassalised polity under a centre of domination, namely the central Kadatuan Srivijaya. The polity was defined by its centre rather than its boundaries and it could be composed of numerous other tributary polities without undergoing further administrative integration.[89]

The relations between the central kadatuan and its member (subscribers) kadatuans were dynamic. As such, the status would shift over generations. Minor trading ports throughout the region were controlled by local vassal rulers in place on behalf of the king. They also presided over harvesting resources from their respective regions for export. A portion of their revenue was required to be paid to the king.[90] They were not allowed to infringe upon international trade relations, but the temptation of keeping more money to themselves eventually led foreign traders and local rulers to conduct illicit trading relations of their own.[91] Other sources claim that the Champa invasion had weakened the central government significantly, forcing vassals to keep the international trade revenue for themselves.[90]

In addition to coercive methods through raids and conquests and being bound by pasumpahan (oath of allegiance), the royalties of each kadatuan often formed alliances through dynastic marriages. For example, a previously suzerained kadatuan over time might rise in prestige and power, so that eventually its ruler could lay claim to be the maharaja of the central kadatuan. The relationship between Srivijayan in Sumatra (descendants of Dapunta Hyang Sri Jayanasa) and Sailendras in Java exemplified this political dynamic.

Economy and commerce

The main interest of Srivijayan foreign economic relations was to secure a highly lucrative trade agreement to serve a large Chinese market, that span from Tang to Song dynasty era. In order to participate in this trade agreement, Srivijaya involved in tributary relation with China, in which they sent numbers of envoys and embassies to secure the Chinese court's favour. The port of Srivijaya served as an important entrepôt in which valuable commodities from the region and beyond are collected, traded and shipped. Rice, cotton, indigo and silver from Java; aloes, resin, camphor, ivory and rhino's tusks, tin and gold from Sumatra and Malay Peninsula; rattan, rare timber, camphor, gems and precious stones from Borneo; exotic birds and rare animals, iron, sappan, sandalwood and rare spices including clove and nutmeg from Eastern Indonesian archipelago; various spices of Southeast Asia and India including pepper, cubeb and cinnamon; also Chinese ceramics, lacquerware, brocade, fabrics, silks and Chinese artworks are among valuable commodities being traded in Srivijayan port. What goods were actually native to Srivijaya is currently being disputed due to the volume of cargo that regularly passed through the region from India, China, and Arabia. Foreign traders stopped to trade their cargo in Srivijaya with other merchants from Southeast Asia and beyond. It was an easy location for traders from different regions to meet as opposed to visiting each other directly. This system of trade has led researchers to conjecture that the actual native products of Srivijaya were far less than what was originally recorded by Chinese and Arabic traders of the time. It may be that cargo sourced from foreign regions accumulated in Srivijaya. The accumulation of particular foreign goods that were easily accessible and in large supply might have given the impression they were products of Srivijaya. This could also work in the opposite direction with some native Srivijayan goods being mistaken as foreign commodities.[92][90] By 1178, Srivijaya mission to China higlighted the Srivijaya's role as intermediary to acquire Borneo product, such as plum flower-shaped Borneo camphor planks.[48]

In the world of commerce, Srivijaya rose rapidly to be a far-flung empire controlling the two passages between India and China, namely the Sunda Strait from Palembang and the Malacca Strait from Kedah. Arab accounts state that the empire of the Srivijayan Maharaja was so vast that the swiftest vessel would not have been able to travel around all its islands within two years. The islands the accounts referred to produced camphor, aloes, sandal-wood, spices like cloves, nutmegs, cardamom and cubebs, as well as ivory, gold and tin, all of which equalled the wealth of the Maharaja to any king in India.[93] The Srivijayan government centralized the sourcing and trading of native and foreign goods in “warehouses” which streamlined the trade process by making a variety of products easily accessible in one area.

Ceramics were a major trade commodity between Srivijaya and China with shard artifacts found along the coast of Sumatra and Java. It is assumed that China and Srivijaya may have had an exclusive ceramics trade relationship because particular ceramic shards can only be found at their point of origin, Guangzhou, or in Indonesia, but nowhere else along the trade route.[92] When trying to prove this theory, there have been some discrepancies with the dating of said artifacts. Ceramic sherds found around the Geding Suro temple complex have been revealed to be much more recent than previously assumed. A statuette found in the same area did align with Srivijayan chronology, but it has been suggested that this is merely a coincidence and the product was actually brought to the region recently.[23]

Other than fostering the lucrative trade relations with India and China, Srivijaya also established commerce links with Arabia. In a highly plausible account, a messenger was sent by Maharaja Sri Indravarman to deliver a letter to Caliph Umar ibn AbdulAziz of Ummayad in 718. The messenger later returned to Srivijaya with a Zanji (a black female slave from Zanj), a gift from the Caliph to the Maharaja. Later, a Chinese chronicle made mention of Shih-li-t-'o-pa-mo (Sri Indravarman) and how the Maharaja of Shih-li-fo-shih had sent the Chinese Emperor a ts'engchi (Chinese spelling of the Arabic Zanji) as a gift in 724.[94]

Arab writers of the 9th and 10th century, in their writings, considered the king of Al-Hind (India and to some extent might include Southeast Asia) as one of the 4 great kings in the world.[95][96] The reference to the kings of Al-Hind might have also included the kings of Southeast Asia; Sumatra, Java, Burma and Cambodia. They are, invariably, depicted by the Arabs writers as extremely powerful and being equipped with vast armies of men, horses and having tens of thousands of elephants.[95][96] They were also said to be in possession of vast treasures of gold and silver.[95][96] Trading records from the 9th and 10th centuries mention Srivijaya, but do not expand upon regions further east thus indicating that Arabic traders were not engaging with other regions in Southeast Asia thus serving as further evidence of Srivijaya's important role as a link between the two regions.[92]

The currency of the empire wwas gold and silver coins embossed with the image of the sandalwood flower (of which Srivijaya had a trade monopoly on) and the word “vara,” or “glory,” in Sanskrit.[90][97] Other items could be used to barter with, such as porcelain, silk, sugar, iron, rice, dried galangal, rhubarb, and camphor.[90] According to Chinese records, gold was a large part of Srivijaya. These texts describe that the empire, also referred to as “Jinzhou” which translates to “Gold Coast”, used gold vessel in ritual offering and that, as a vassal to China, brought “golden lotus bowls” as luxurious gifts to the Emperor during the Song Dynasty.[98] Some Arabic records that the profits acquired from trade ports and levies were converted into gold and hidden by the King in the royal pond.[6]

Thalassocratic empire

The Srivijayan empire was a coastal trading centre and was a thalassocracy. As such, its influence did not extend far beyond the coastal areas of the islands of Southeast Asia.

Srivijaya benefited from the lucrative maritime trade between China and India as well as trading in products such as Maluku spices within the Malay Archipelago. Serving as Southeast Asia's main entrepôt and gaining trade patronage by the Chinese court, Srivijaya was constantly managing its trade networks and, yet, always wary of potential rival ports of its neighbouring kingdoms. A majority of the revenue from international trade was used to finance the military which was charged with the responsibility of protecting the ports. Some records even describe the use of iron chains to prevent pirate attacks.[90] The necessity to maintain its trade monopoly had led the empire to launch naval military expeditions against rival ports in Southeast Asia and to absorb them into Srivijaya's sphere of influence. The port of Malayu in Jambi, Kota Kapur in Bangka island, Tarumanagara and the port of Sunda in West Java, Kalingga in Central Java, the port of Kedah and Chaiya in Malay peninsula are among the regional ports that were absorbed within Srivijayan sphere of influence. A series of Javan-Srivijaya raids on the ports of Champa and Cambodia was also part of its effort to maintain its monopoly in the region by sacking its rival ports.

The maritime prowess was recorded in a Borobudur bas relief of Borobudur ship, the 8th century wooden double outrigger vehicles of Maritime Southeast Asia. The function of an outrigger is to stabilise the ship. The single or double outrigger canoe is the typical feature of the seafaring Austronesians vessels and the most likely type of vessel used for the voyages and explorations across Southeast Asia, Oceania, and the Indian Ocean. The ships depicted at Borobudur most likely were the type of vessels used for inter-insular trades and naval campaigns by Sailendra and Srivijaya.

The Srivijayan empire exercised its influence mainly around the coastal areas of Southeast Asia, with the exception of contributing to the population of Madagascar 3,300 miles (8,000 kilometres) to the west.[50] The migration to Madagascar was estimated to have taken place 1,200 years ago around 830.[51]

Culture and society

Srivijaya-Palembang's significance both as a center for trade and for the practice of Vajrayana Buddhism has been established by Arab and Chinese historical records over several centuries. Srivijaya' own historical documents, inscriptions in Old Malay, are limited to the second half of the 7th century. The inscriptions uncover the hierarchical leadership system, in which the king is served by many other high-status officials.[99] A complex, stratified, cosmopolitan and prosperous society with refined tastes in art, literature and culture, with complex set of rituals, influenced by Mahayana Buddhist faith; blossomed in the ancient Srivijayan society. Their complex social order can be seen through studies on the inscriptions, foreign accounts, as well as rich portrayal in bas-reliefs of temples from this period. Their accomplished artistry was evidenced from a number of Srivijayan Art Mahayana Buddhist statues discovered in the region. The kingdom had developed a complex society; which characterised by heterogeneity of their society, inequality of social stratification, and the formation of national administrative institution in their kingdom. Some forms of metallurgy were used as jewelry, currency (coins), as status symbols—for decorative purposes.[100]

Art and culture

Trade allowed the spread of art to proliferate. Some art was heavily influenced by Buddhism, further spreading religion and ideologies through the trade of art. The Buddhist art and architecture of Srivijaya was influenced by the Indian art of the Gupta Empire and Pala Empire. This is evident in the Indian Amaravati style Buddha statue located in Palembang. This statue, dating back to the 7th and 8th centuries, exists as proof of the spread of art, culture, and ideology through the medium of trade.[101][90] According to various historical sources, a complex and cosmopolitan society with a refined culture, deeply influenced by Vajrayana Buddhism, flourished in the Srivijayan capital. The 7th century Talang Tuwo inscription described Buddhist rituals and blessings at the auspicious event of establishing public park. This inscription allowed historians to understand the practices being held at the time, as well as their importance to the function of Srivijayan society. Talang Tuwo serves as one of the world's oldest inscriptions that talks about the environment, highlighting the centrality of nature in Buddhist religion and further, Srivijayan society. The Kota Kapur Inscription mentions Srivijaya military dominance against Java. These inscriptions were in the Old Malay language, the language used by Srivijaya and also the ancestor of Malay and Indonesian language. Since the 7th century, the Old Malay language has been used in Nusantara (Malay-Indonesian archipelago), marked by these Srivijayan inscriptions and other inscriptions using old Malay language in the coastal areas of the archipelago, such as those discovered in Java. The trade contact carried by the traders at the time was the main vehicle to spread Malay language, since it was the language used amongst the traders. By then, Malay language become lingua franca and was spoken widely by most people in the archipelago.[102][103][90]

However, despite its economic, cultural and military prowess, Srivijaya left few archaeological remains in their heartlands in Sumatra, in contrast with Srivijayan episode in Central Java during the leadership of Sailendras that produced numerous monuments; such as the Kalasan, Sewu and Borobudur mandala. The Buddhist temples dated from Srivijayan era in Sumatra are Muaro Jambi, Muara Takus and Biaro Bahal.

Some Buddhist sculptures, such as Buddha Vairocana, Boddhisattva Avalokiteshvara and Maitreya, were discovered in numerous sites in Sumatra and Malay Peninsula. These archaeological findings such as stone statue of Buddha discovered in Bukit Seguntang, Palembang,[104] Avalokiteshvara from Bingin Jungut in Musi Rawas, bronze Maitreya statue of Komering, all discovered in South Sumatra. In Jambi, golden statue of Avalokiteshvara were discovered in Rataukapastuo, Muarabulian.[105] In Malay Peninsula the bronze statue of Avalokiteshvara of Bidor discovered in Perak Malaysia,[106] and Avalokiteshvara of Chaiya in Southern Thailand.[107] All of these statues demonstrated the same elegance and common style identified as "Srivijayan art" that reflects close resemblance — probably inspired — by both Indian Amaravati style and Javanese Sailendra art (c. 8th to 9th century).[108] The difference in material, yet overarching theme of Buddhism found across the region supports the spread of Buddhism through trade. Although each country put their own spin on an idea, it is evident how trade played a huge role in spreading ideas throughout Southeast Asia, especially in Srivijaya. The commonality of Srivijayan art exists in Southeast Asian sites, proving their influence on art and architecture across the region. Without trade, Srivijayan art could not have proliferated, and cross-cultural exchanges of language and style could not have been achieved.

After the bronze and Iron Age, an influx of bronze tools and jewelry spread throughout the region. The different styles of bangles and beads represent the different regions of origin and their own specific materials and techniques used. Chinese artworks were one of the main items traded in the region, spreading art styles enveloped in ceramics, pottery, fabrics, silk, and artworks.[90]

Religion

— from I-tsing's A Record of Buddhist Practices Sent Home from the Southern Sea.[109]

Remnants of Buddhist shrines (stupas) near Palembang and in neighboring areas aid researchers in their understanding of the Buddhism within this society. Srivijaya and its kings were instrumental in the spread of Buddhism as they established it in places they conquered like Java, Malaya, and other lands.[110] People making pilgrimages were encouraged to spend time with the monks in the capital city of Palembang on their journey to India.[110]

Other than Palembang, in Srivijayan realm of Sumatra, three archaeological sites are notable for their Buddhist temple density. They are Muaro Jambi by the bank of Batang Hari River in Jambi province; Muara Takus stupas in Kampar River valley of Riau province; and Biaro Bahal temple compound in Barumun and Pannai river valleys, North Sumatra province. It is highly possible that these Buddhist sites served as sangha community; the monastic Buddhist learning centers of the region, which attracts students and scholars from all over Asia.

250 years before I Ching, scholar and traveler, Fa Xian, did not notice the heavy hand of Buddhism within the Srivijayan region. Fa Xian, however, did witness the maritime competition over the region and observed the rise of Srivijaya as a Thalassocracy.[98] I-Tsing stayed in Srivijaya for six months and studied Sanskrit. According to I-Tsing, within Palembang there were more than 1000 monks studying for themselves and training traveling scholars who were going from India to China and vice versa. These travelers were primarily situated in Palembang for long periods of time due to waiting for Monsoon winds to help further their journey.[111]

A stronghold of Vajrayana Buddhism, Srivijaya attracted pilgrims and scholars from other parts of Asia. These included the Chinese monk I Ching, who made several lengthy visits to Sumatra on his way to study at Nalanda University in India in 671 and 695, and the 11th century Bengali Buddhist scholar Atisha, who played a major role in the development of Vajrayana Buddhism in Tibet. I Ching, also known as Yijing, and other monks of his time practised a pure version of Buddhism although the religion allowed for culture changes to be made.[112] He is also given credit for translating Buddhist text which has the most instructions on the discipline of the religion.[113] I Ching reports that the kingdom was home to more than a thousand Buddhist scholars; it was in Srivijaya that he wrote his memoir of Buddhism during his own lifetime. Travellers to these islands mentioned that gold coins were in use in the coastal areas but not inland.

A notable Srivijayan and revered Buddhist scholar is Dharmakirti who taught Buddhist philosophy in Srivijaya and Nalanda. The language diction of many inscriptions found near where Srivijaya once reigned incorporated Indian Tantric conceptions. This evidence makes it clear the relationship of the ruler and the concept of bodhisattva—one who was to become a Buddha. This is the first evidence seen in the archaeological record of a Southeast Asian ruler (or king) regarded as a religious leader/figure.

One thing researchers have found Srivijaya to be lacking is an emphasis in art and architecture. While neighboring regions have evidence of intricate architecture, such as the Borobudur temple built in 750-850 AD under the Saliendra Dynasty, Palembang lacks Buddhist stupas or sculpture.[114] Though this does not accurately reflect Buddhist influence.

Relations with regional powers

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Singapore | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Early history (pre-1819)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

British colonial era (1819–1942)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Japanese Occupation (1942–1945)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Post-war period (1945–1962)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Internal self-government (1955–1963)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Merger with Malaysia (1963–1965) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Republic of Singapore (1965–present)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Although historical records and archaeological evidence are scarce, it appears that by the 7th century, Srivijaya had established suzerainty over large areas of Sumatra, western Java and much of the Malay Peninsula. The oldest accounts of the empire come from Arabic and Chinese traders who noted in their travel logs the importance of the empire in regional trade.[115] Its location was instrumental in developing itself as a major connecting port between China and the Middle East and Southeast Asia. Control of the Malacca and Sunda Straits meant it controlled both the spice route traffic and local trade, charging a toll on passing ships. Serving as an entrepôt for Chinese, Malay, and Indian markets, the port of Palembang, accessible from the coast by way of a river, accumulated great wealth. Instead of traveling the entire distance from the Middle East to China, which would have taken about a year with the assistance of monsoon winds, it was easier to stop somewhere in the middle, Srivijaya. It took about half a year from either direction to reach Srivijaya which was a far more effective and efficient use of manpower and resources. A round trip from one end to Srivijaya and back would take the same amount of time to go the entire distance one way. This theory has been supported by evidence found in two local shipwrecks. One off the coast of Belitung, an island east of Sumatra, and another near Cirebon, a coastal city on the nearby island of Java. Both ships carried a variety of foreign cargo and, in the case of the Belitung wreck, had foreign origins.[92]

The Melayu Kingdom was the first rival power centre absorbed into the empire, and thus began the domination of the region through trade and conquest in the 7th through the 9th centuries. The Melayu Kingdom's gold mines up in the Batang Hari River hinterland were a crucial economic resource and may be the origin of the word Suvarnadvipa, the Sanskrit name for Sumatra. Srivijaya helped spread the Malay culture throughout Sumatra, the Malay Peninsula, and western Borneo. Its influence waned in the 11th century. It was then in frequent conflict with, and ultimately subjugated by, the Javanese kingdoms of Singhasari and, later, Majapahit.[116] This was not the first time the Srivijayans had a conflict with the Javanese. According to historian Paul Michel Munoz, the Javanese Sanjaya dynasty was a strong rival of Srivijaya in the 8th century when the Srivijayan capital was located in Java. The seat of the empire moved to Muaro Jambi in the last centuries of Srivijaya's existence.

The Khmer Empire might also have been a tributary state in its early stages. The Khmer king, Jayavarman II, was mentioned to have spent years in the court of Sailendra in Java before returning to Cambodia to rule around 790. Influenced by the Javanese culture of the Sailendran-Srivijayan mandala (and likely eager to emulate the Javanese model in his court), he proclaimed Cambodian independence from Java and ruled as devaraja, establishing Khmer empire and starting the Angkor era.[117]

Some historians claim that Chaiya in Surat Thani Province in southern Thailand was, at least temporarily, the capital of Srivijaya, but this claim is widely disputed. However, Chaiya was probably a regional centre of the kingdom. The temple of Borom That in Chaiya contains a reconstructed pagoda in Srivijaya style.[79]

Wat Phra Boromathat Chaiya is highlighted by the pagoda in Srivijaya style, elaborately restored, and dating back to the 7th century. The Buddha relics are enshrined in the chedi or stupa. In the surrounding chapels are several Buddha statues in Srivijaya style, as it was labelled by Damrong Rajanubhab in his Collected Inscriptions of Siam, which is now attributed to Wat Hua Wiang in Chaiya. Dated to the year 697 of the Mahasakkarat era (775), the inscriptions on a bai sema tells about the King of Srivijaya having erected three stupas at that site; which are possibly the ones at Wat Phra Borom That. However, it is also possible that the three stupas referred to are located at Wat Hua Wiang (Hua Wiang temple), Wat Lhong (Lhong temple) and Wat Kaew (Kaew temple) which are also found in Chaiya. After the fall of the Srivijaya, the area was divided into the cities (mueang) Chaiya, Thatong (now Kanchanadit) and Khirirat Nikhom.

Srivijaya also maintained close relations with the Pala Empire in Bengal. The Nalanda inscription, dated 860, records that Maharaja Balaputra dedicated a monastery at the Nalanda university in the Pala territory.[3]:109 The relation between Srivijaya and the Chola dynasty of southern India was initially friendly during the reign of Raja Raja Chola I. In 1006, a Srivijayan Maharaja from the Sailendra dynasty, king Maravijayattungavarman, constructed the Chudamani Vihara in the port town of Nagapattinam.[118] However, during the reign of Rajendra Chola I the relationship deteriorated as the Chola Dynasty started to attack Srivijayan cities.[119]

The reason for this sudden change in the relationship with the Chola kingdom is not really known. However, as some historians suggest, it would seem that the Khmer king, Suryavarman I of the Khmer Empire, had requested aid from Emperor Rajendra Chola I of the Chola dynasty against Tambralinga.[120] After learning of Suryavarman's alliance with Rajendra Chola, the Tambralinga kingdom requested aid from the Srivijaya king, Sangrama Vijayatungavarman.[120][121] This eventually led to the Chola Empire coming into conflict with the Srivijiya Empire. The conflict ended with a victory for the Chola and heavy losses for Srivijaya and the capture of Sangramavijayottungavarman in the Chola raid in 1025.[3]:142–143[120][121] During the reign of Kulothunga Chola I, Srivijaya had sent an embassy to the Chola Dynasty.[61][122]

Legacy

Although Srivijaya left few archaeological remains and was almost forgotten in the collective memory of the Malay people, the rediscovery of this ancient maritime empire by Cœdès in the 1920s raised the notion that it was possible for a widespread political entity to have thrived in Southeast Asia in the past. Modern Indonesian historians have invoked Srivijaya not merely as a glorification of the past, but as a frame of reference and example of how ancient globalisation, foreign relations and maritime trade, has shaped Asian civilisation.[123]