Yoruba people

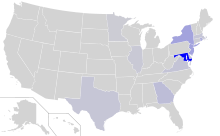

The Yoruba people (Yoruba: Ìran Yorùbá) are an ethnic group that inhabits western Africa, mainly Nigeria, Benin, Togo and part of Ghana. The Yoruba constitute around 57-60 million people worldwide. The vast majority of this population is from Nigeria, where the Yoruba make up 21% of the country's population[8] making them one of the largest ethnic groups in Africa. Most Yoruba people speak the Yoruba language, which is the Niger-Congo language with the largest number of native speakers.[9]

A Yoruba children's cultural troupe from the 1990s in Lagos | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 57-60 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 55.9 million[1] | |

| 1.7 million[2] | |

| 469,000 (2017)[3] | |

| 304,000 (2014)[4] | |

| 120,000 (2017)[5][6] | |

| Languages | |

| Yoruba and Yoruboid languages Others: English or French | |

| Religion | |

| [7] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Main: Aja, Aku, Ebira, Ewe, Fon, Ga, Gbagyi, Igala, Itsekiri, Mahi, Nagos, Nupe Edo: Afemai, Bini, Esan, Etsako, Isoko, Owan, Urhobo Gur peoples: Bariba, Dagomba, Gurma, Gurunsi, Mossi, Somba | |

| Part of a series on |

| Yoruba people |

|---|

|

| Subgroups |

| Music |

|

Contemporary: Folk/Traditional: |

| Notable personalities |

| List of Yoruba people |

| Religion |

| Diaspora |

|

| Festivals and events |

|

West Africa:

Diaspora:

|

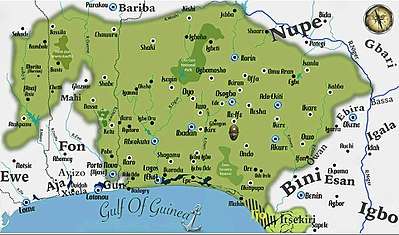

The Yoruba share borders with the very closely related Itsekiri to the south-east in the North West Niger delta (who are ancestrally related to the Yoruba, choose to maintain a distinct cultural identity), Bariba to the north in Benin and Nigeria, the Nupe also to the north and the Ebira to the northeast in central Nigeria. To the east are the Edo, Ẹsan and the Afemai groups in mid-western Nigeria. Adjacent to the Ebira and Edo groups are the related Igala people found in the northeast, on the left bank of the Niger River. To the southwest are the Gbe speaking Mahi, Gun, Fon and Ewe who border Yoruba communities in Benin and Togo. Significant Yoruba populations in other West African countries can be found in Ghana,[10][11][12] Benin,[10] Ivory Coast,[13] and Sierra Leone.[14]

The Yoruba diaspora consists of two main groupings; first were Yoruba's dispersed through Atlantic slave trade mainly to the western hemisphere and the second wave includes relatively recent migrants, the majority of which moved to the United Kingdom and the United States after major economic and political changes in the 1960s to 1980s.[15]

Etymology

As an ethnic description, the word "Yoruba" (or "Yaraba" as Hausas called Yoruba people in their dialect) was originally in reference to the Oyo Empire and is the usual Hausa name for Oyo people as noted by Hugh Clapperton and Richard Lander.[16] It was therefore popularized by Hausa usage[17] and ethnography written in Ajami during the 19th century by Sultan Muhammad Bello. The extension of the term to all speakers of dialects related to the language of the Oyo (in modern terminology North-West Yoruba) dates to the second half of the 19th century. It is due to the influence of Bishop Samuel Ajayi Crowther, the first Anglican bishop in Nigeria. Crowther was himself an Oyo Yoruba and compiled the first Yoruba dictionary as well as introducing a standard for Yoruba orthography.[18][19] The alternative name Akú, derived from the first words of Yoruba greetings (such as Ẹ kú àárọ? "good morning", Ẹ kú alẹ? "good evening") has survived in certain parts of their diaspora as a self-descriptive, especially in Sierra Leone.[17][20][21]

Language

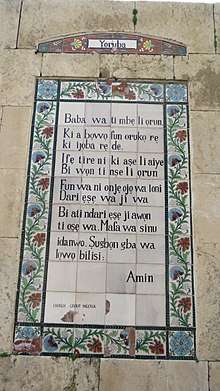

The Yoruba culture was originally an oral tradition, and the majority of Yoruba people are native speakers of the Yoruba language. The number of speakers is roughly estimated at about 30 million in 2010.[22] Yoruba is classified within the Edekiri languages, which together with the isolate Igala, form the Yoruboid group of languages within what we now have as West Africa. Igala and Yoruba have important historical and cultural relationships. The languages of the two ethnic groups bear such a close resemblance that researchers such as Forde (1951) and Westermann and Bryan (1952) regarded Igala as a dialect of Yoruba.

The Yoruboid languages are assumed to have developed out of an undifferentiated Volta-Niger group by the 1st millennium BCE. There are three major dialect areas: Northwest, Central, and Southeast.[23] As the North-West Yoruba dialects show more linguistic innovation, combined with the fact that Southeast and Central Yoruba areas generally have older settlements, suggests a later date of immigration into Northwestern Yoruba territory.[24] The area where North-West Yoruba (NWY) is spoken corresponds to the historical Oyo Empire. South-East Yoruba (SEY) was closely associated with the expansion of the Benin Empire after c. 1450.[25] Central Yoruba forms a transitional area in that the lexicon has much in common with NWY, whereas it shares many ethnographical features with SEY.

Literary Yoruba is the standard variety taught in schools and spoken by newsreaders on the radio. It is mostly entirely based on northwestern Yoruba dialects of the Oyos and the Egbas, and has its origins in two sources; The work of Yoruba Christian missionaries based mostly in the Egba hinterland at Abeokuta, and the Yoruba grammar compiled in the 1850s by Bishop Crowther, who himself was a Sierra Leonean creole of Oyo origin. This was exemplified by the following remark by Adetugbọ (1967), as cited in Fagborun (1994): "While the orthography agreed upon by the missionaries represented to a very large degree the phonemes of the Abẹokuta dialect, the morpho-syntax reflected the Ọyọ-Ibadan dialects".

History

As of the 7th century BCE the African peoples who lived in Yorubaland were not initially known as the Yoruba, although they shared a common ethnicity and language group. By the 8th century, a powerful kingdom already existed in Ile-Ife, one of the earliest in Africa.[26] It is said to be ile-gbo(netherworld ruler based on the oldest predynastic rulers being associated with Oba Tala, Oro-gbo(Shango) Otete(Oduduwa) .[27]

The historical Yoruba develop in situ, out of earlier Mesolithic Volta-Niger populations, by the 1st millennium BCE.[28] Oral history recorded under the Oyo Empire derives the Yoruba as an ethnic group from the population of the older kingdom of Ile-Ife. The Yoruba were the dominant cultural force in southern and Northern, Eastern Nigeria as far back as the 11th century.[29]

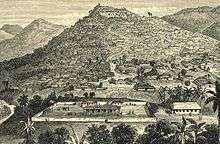

The Yoruba are among the most urbanized people in Africa. For centuries before the arrival of the British colonial administration most Yoruba already lived in well structured urban centres organized around powerful city-states (Ìlú) centred around the residence of the Oba.[30] In ancient times, most of these cities were fortresses, with high walls and gates.[31] Yoruba cities have always been among the most populous in Africa. Archaeological findings indicate that Òyó-Ilé or Katunga, capital of the Yoruba empire of Oyo (fl. between the 11th and 19th centuries CE), had a population of over 100,000 people (the largest single population of any African settlement at that time in history).[28] For a long time also, Ibadan, one of the major Yoruba cities and founded in the 1800s, was the largest city in the whole of Sub Saharan Africa. Today, Lagos (Yoruba: Èkó), another major Yoruba city, with a population of over twenty million, remains the largest on the African continent.[32]

Archaeologically, the settlement of Ile-Ife showed features of urbanism in the 12th–14th century era.[31] In the period around 1300 CE the artists at Ile-Ife developed a refined and naturalistic sculptural tradition in terracotta, stone and copper alloy – copper, brass, and bronze many of which appear to have been created under the patronage of King Obalufon II, the man who today is identified as the Yoruba patron deity of brass casting, weaving and regalia.[33] The dynasty of kings at Ile-Ife, which is regarded by the Yoruba as the place of origin of human civilization, remains intact to this day. The urban phase of Ile-Ife before the rise of Oyo, c. 1100–1600, a significant peak of political centralization in the 12th century,[34][35] is commonly described as a "golden age" of Ile-Ife. The oba or ruler of Ile-Ife is referred to as the Ooni of Ife.[36][37]

Oyo and Ile-Ife

.jpg)

Ife continues to be seen as the "Spiritual Homeland" of the Yoruba. The city was surpassed by the Oyo Empire[38] as the dominant Yoruba military and political power in the 11th century.[39]

The Oyo Empire under its oba, known as the Alaafin of Oyo, was active in the African slave trade during the 18th century. The Yoruba often demanded slaves as a form of tribute of subject populations,[40] who in turn sometimes made war on other peoples to capture the required slaves. Part of the slaves sold by the Oyo Empire entered the Atlantic slave trade.[41][42]

Most of the city states[43] were controlled by Obas (or royal sovereigns with various individual titles) and councils made up of Oloyes, recognised leaders of royal, noble and, often, even common descent, who joined them in ruling over the kingdoms through a series of guilds and cults. Different states saw differing ratios of power between the kingships and the chiefs' councils. Some, such as Oyo, had powerful, autocratic monarchs with almost total control, while in others such as the Ijebu city-states,[43] the senatorial councils held more influence and the power of the ruler or Ọba, referred to as the Awujale of Ijebuland, was more limited.[37]

Yoruba settlements are often described as primarily one or more of the main social groupings called "generations":[44]

- The "first generation" includes towns and cities[43] known as original capitals of founding Yoruba kingdoms or states.

- The "second generation" consists of settlements created by conquest.[43]

- The "third generation" consists of villages and municipalities that emerged following the internecine wars of the 19th century.

Pre-colonial government of Yoruba society

Government

Monarchies were a common form of government in Yorubaland, but they were not the only approach to government and social organization. The numerous Ijebu city-states to the west of Oyo and the Ẹgba communities, found in the forests below Ọyọ's savanna region, were notable exceptions. These independent polities often elected an Ọba, though real political, legislative, and judicial powers resided with the Ogboni, a council of notable elders. The notion of the divine king was so important to the Yoruba, however, that it has been part of their organization in its various forms from their antiquity to the contemporary era.

During the internecine wars of the 19th century, the Ijebu forced citizens of more than 150 Ẹgba and Owu communities to migrate to the fortified city of Abeokuta. Each quarter retained its own Ogboni council of civilian leaders, along with an Olorogun, or council of military leaders, and in some cases its own elected Obas or Baales. These independent councils elected their most capable members to join a federal civilian and military council that represented the city as a whole. Commander Frederick Forbes, a representative of the British Crown writing an account of his visit to the city in the Church Military Intelligencer (1853),[45] described Abẹokuta as having "four presidents", and the system of government as having "840 principal rulers or 'House of Lords,' 2800 secondary chiefs or 'House of Commons,' 140 principal military ones and 280 secondary ones."[46] He described Abẹokuta and its system of government as "the most extraordinary republic in the world."[46]

Leadership

Gerontocratic leadership councils that guarded against the monopolization of power by a monarch were a trait of the Ẹgba, according to the eminent Ọyọ historian Reverend Samuel Johnson. Such councils were also well-developed among the northern Okun groups, the eastern Ekiti, and other groups falling under the Yoruba ethnic umbrella. In Ọyọ, the most centralized of the precolonial kingdoms, the Alaafin consulted on all political decisions with the prime minister and principal kingmaker (the Basọrun) and the rest of the council of leading nobles known as the Ọyọ Mesi.

Traditionally kingship and chieftainship were not determined by simple primogeniture, as in most monarchic systems of government. An electoral college of lineage heads was and still is usually charged with selecting a member of one of the royal families from any given realm, and the selection is then confirmed by an Ifá oracular request. The Ọbas live in palaces that are usually in the center of the town. Opposite the king's palace is the Ọja Ọba, or the king's market. These markets form an inherent part of Yoruba life. Traditionally their traders are well organized, have various guilds, officers, and an elected speaker. They also often have at least one Iyaloja, or Lady of the Market,[47][48] who is expected to represent their interests in the aristocratic council of oloyes at the palace.

City-states

The monarchy of any city-state was usually limited to a number of royal lineages.[50] A family could be excluded from kingship and chieftaincy if any family member, servant, or slave belonging to the family committed a crime, such as theft, fraud, murder or rape. In other city-states, the monarchy was open to the election of any free-born male citizen. In Ilesa, Ondo, Akure and other Yoruba communities, there were several, but comparatively rare, traditions of female Ọbas. The kings were traditionally almost always polygamous and often married royal family members from other domains, thereby creating useful alliances with other rulers. Ibadan, a city-state and proto-empire that was founded in the 1800s by a polyglot group of refugees, soldiers, and itinerant traders after the fall of Ọyọ, largely dispensed with the concept of monarchism, preferring to elect both military and civil councils from a pool of eminent citizens. The city became a military republic, with distinguished soldiers wielding political power through their election by popular acclaim and the respect of their peers. Similar practices were adopted by the Ijẹsa and other groups, which saw a corresponding rise in the social influence of military adventurers and successful entrepreneurs. The Ìgbómìnà were renowned for their agricultural and hunting prowess, as well as their woodcarving, leather art, and the famous Elewe masquerade.

Groups, organizations and leagues in Yorubaland

Occupational guilds, social clubs, secret or initiatory societies, and religious units, commonly known as Ẹgbẹ in Yoruba, included the Parakoyi (or league of traders) and Ẹgbẹ Ọdẹ (hunter's guild), and maintained an important role in commerce, social control, and vocational education in Yoruba polities. There are also examples of other peer organizations in the region.[51][52][53][54] When the Ẹgba resisted the imperial domination of the Ọyọ Empire, a figure named Lisabi is credited with either creating or reviving a covert traditional organization named Ẹgbẹ Aro. This group, originally a farmers' union, was converted to a network of secret militias throughout the Ẹgba forests, and each lodge plotted and successfully managed to overthrow Ọyọ's Ajeles (appointed administrators) in the late 18th century.

Similarly, covert military resistance leagues like the Ekiti Parapọ and the Ogidi alliance were organized during the 19th century wars by often-decentralized communities of the Ekiti, Ijẹsa, Ìgbómìnà and Okun Yoruba in order to resist various imperial expansionist plans of Ibadan, Nupe, and the Sokoto Caliphate.

Society and culture

In the city-states and many of their neighbours, a reserved way of life remains, with the school of thought of their people serving as a major influence in West Africa and elsewhere.

Today, most contemporary Yoruba are Christians or Muslims.[7] Be that as it may, many of the principles of the traditional faith of their ancestors are either knowingly or unknowingly upheld by a significant proportion of the populations of Nigeria, Benin and Togo.[55]

Religion and mythology

Traditional Yoruba religion

The Yoruba religion comprises the traditional religious and spiritual concepts and practices of the Yoruba people.[56] Its homeland is in Southwestern Nigeria and the adjoining parts of Benin and Togo, a region that has come to be known as Yorubaland. Yoruba religion is formed of diverse traditions and has no single founder.[57] Yoruba religious beliefs are part of itan, the total complex of songs, histories, stories and other cultural concepts that make up the Yoruba society.[57]

One of the most common Yoruba traditional religious concepts has been the concept of Orisa. Orisa (also spelled Orisha or Orixa) are various godly forms that reflect one of the various manifestations or avatars of God in the Yoruba religious system. Some widely known Orisa are Ogun, (a god of metal, war and victory), Shango or Jakuta (a god of thunder, lightning, fire and justice who manifests as a king and who always wields a double-edged axe that conveys his divine authority and power), Esu Elegbara (a trickster who serves as the sole messenger of the pantheon, and who conveys the wish of men to the gods. He understands every language spoken by humankind, and is also the guardian of the crossroads, Oríta méta in Yoruba) and Orunmila (a god of the Oracle). Eshu has two avatar forms, which are manifestations of his dual nature – positive and negative energies; Eshu Laroye, a teacher instructor and leader, and Eshu Ebita, a jester, deceitful, suggestive and cunning.[58] Orunmila, for his part, reveals the past, gives solutions to problems in the present, and influences the future through the Ifa divination system, which is practised by oracle priests called Babalawos.

Olorun is one of the principal manifestations of the Supreme God of the Yoruba pantheon, the owner of the heavens, and is associated with the Sun known as Oòrùn in the Yoruba language. The two other principal forms of the supreme God are Olodumare—the supreme creator—and Olofin, who is the conduit between Òrunn (Heaven) and Ayé (Earth). Oshumare is a god that manifests in the form of a rainbow, also known as Òsùmàrè in Yoruba, while Obatala is the god of clarity and creativity.,[60][30] as well as in some aspects of Umbanda, Winti, Obeah, Vodun and a host of others. These varieties, or spiritual lineages as they are called, are practiced throughout areas of Nigeria, among others. As interest in African indigenous religions grows, Orisa communities and lineages can be found in parts of Europe and Asia as well. While estimates may vary, some scholars believe that there could be more than 100 million adherents of this spiritual tradition worldwide.[61]

Mythology

Oral history of the Oyo-Yoruba recounts Odùduwà to be the progenitor of the Yoruba and the reigning ancestor of their crowned kings.

He came from the east, sometimes understood from Ife traditions to be Oke-Ora and by other sources as the "vicinity" true East on the Cardinal points, but more likely signifying the region of Ekiti and Okun sub-communities in northeastern Yorubaland in central Nigeria. Ekiti is near the confluence of the Niger and Benue rivers, and is where the Yoruba language is presumed to have separated from related ethno-linguistic groups like Igala, Igbo, and Edo.[62]

After the death of Oduduwa, there was a dispersal of his children from Ife to found other kingdoms. Each child made his or her mark in the subsequent urbanization and consolidation of the Yoruba confederacy of kingdoms, with each kingdom tracing its origin due to them to Ile-Ife.

After the dispersal, the aborigines became difficult, and constituted a serious threat to the survival of Ife. Thought to be survivors of the old occupants of the land before the arrival of Oduduwa, these people now turned themselves into marauders. They would come to town in costumes made of raffia with terrible and fearsome appearances, and burn down houses and loot the markets. Then came Moremi on the scene; she was said to have played a significant role in the quelling of the marauders advancements. But this was at a great price; having to give up her only son Oluorogbo. The reward for her patriotism and selflessness was not to be reaped in one lifetime as she later passed on and was thereafter deified. The Edi festival celebrates this feat amongst her Yoruba descendants.[63]

Philosophy

Yoruba culture consists of cultural philosophy, religion and folktales. They are embodied in Ifa divination, and are known as the tripartite Book of Enlightenment in Yorubaland and in its diaspora.

Yoruba cultural thought is a witness of two epochs. The first epoch is a history of cosmogony and cosmology. This is also an epoch-making history in the oral culture during which time Oduduwa was the king, the Bringer of Light, pioneer of Yoruba folk philosophy, and a prominent diviner. He pondered the visible and invisible worlds, reminiscing about cosmogony, cosmology, and the mythological creatures in the visible and invisible worlds. His time favored the artist-philosophers who produced magnificent naturalistic artworks of civilization during the pre-dynastic period in Yorubaland.The second epoch is the epoch of metaphysical discourse, and the birth of modern artist-philosophy. This commenced in the 19th century in terms of the academic prowess of Bishop Samuel Ajayi Crowther (1807–1891). Although religion is often first in Yoruba culture, nonetheless, it is the philosophy – the thought of man – that actually leads spiritual consciousness (ori) to the creation and the practice of religion. Thus, it is believed that thought (philosophy) is an antecedent to religion. Values such as respect, peaceful co-existence, loyalty and freedom of speech are both upheld and highly valued in Yoruba culture. Societies that are considered secret societies often strictly guard and encourage the observance of moral values. Today, the academic and nonacademic communities are becoming more interested in Yoruba culture. More research is being carried out on Yoruba cultural thought as more books are being written on the subject.

Islam and Christianity

The Yoruba are traditionally very religious people, and are today pluralistic in their religious convictions.[64] The Yoruba are one of the more religiously diverse ethnic groups in Africa. Some Yorubas adhere to Sunni Islam while many follow various Christian denominations, while few others are Shia Muslims too, and large numbers practitioners of the traditional Yoruba religion. Yoruba religious practices such as the Eyo and Osun-Osogbo festivals are witnessing a resurgence in popularity in contemporary Yorubaland. They are largely seen by the adherents of the modern faiths as cultural, rather than religious, events. They participate in them as a means to celebrate their people's history, and boost tourism in their local economies.[55]

Christianity

The Yorubas were one of the first groups in West Africa to be introduced to Christianity on a large scale.[65] Christianity (along with western civilization) came into Yorubaland in the mid-19th century through the Europeans, whose original mission was commerce.[64][66][67][68] The first European visitors were the Portuguese, they visited the Bini kingdom in the late 16th century. As time progressed, other Europeans - such as the French, the British, and the Germans, followed suit. British and French people were the most successful in their quest for colonies (These Europeans actually split Yorubaland, with the larger part being in British Nigeria, and the minor parts in French Dahomey, now Benin, and German Togoland). Home governments encouraged religious organizations to come. Roman Catholics (known to the Yorubas as Ijo Aguda, so named after returning former Yoruba slaves from Latin America, who were mostly Catholic, and were also known as the Agudas, Saros or Amaros) started the race, followed by Protestants, whose prominent member – Church Mission Society (CMS) based in England made the most significant in-roads into the hinterland regions for evangelism and became the largest of the Christian missions. Methodists (known as Ijo-Eleto, so named after the Yoruba word for "method or process") started missions in Agbadarigi / Gbegle by Thomas Birch Freeman in 1842. Henry Townsend, C.C.Gollmer, and Ajayi Crowther of the CMS worked in Abeokuta, then under the Egba division of Southern Nigeria in 1846.[69]

Hinderer and Mann of CMS started missions in Ibadan / Ibarapa and Ijaye divisions of the present Oyo state in 1853. Baptist missionaries – Bowen and Clarke – concentrated on the northern Yoruba axis – (Ogbomoso and environs). With their success, other religious groups – the Salvation Army and the Evangelists Commission of West Africa – became popular among the Igbomina, and other non-denominational Christian groups joined. The increased tempo of Christianity led to the appointment of Saros and indigenes as missionaries. This move was initiated by Venn, the CMS Secretary. Nevertheless, the impact of Christianity in Yorubaland was not felt until the fourth decade of the 19th century, when a Yoruba slave boy, Samuel Ajayi Crowther, became a Christian convert, linguist and minister whose knowledge in languages would become a major tool and instrument to propagate Christianity in Yorubaland and beyond.[70] Today, there are a number of Yoruba Pastors and Church founders with large congregations, e.g. Pastor Enoch Adeboye of the Redeemed Christian Church of God, Pastor David Oyedepo of Living Faith Church World Wide also known as Winners Chapel, Pastor Tunde Bakare of Latter Rain Assembly, Prophet T. B. Joshua of Synagogue Church of All Nations, William Folorunso Kumuyi of Deeper Christian Life Ministry and Dr. Daniel Olukoya of the Mountain of Fire and Miracles Ministries.

Islam

Islam came into Yorubaland around the 14th century, as a result of trade with Hausa and Wangara (also Wankore) merchants, a mobile caste of the Soninkes from the then Mali Empire who entered Yorubaland (Oyo) from the northwestern flank through the Bariba or Borgu corridor,[71] during the reign of Mansa Kankan Musa.[72] Due to this, Islam is traditionally known to the Yoruba as Esin Male or simply Imale i.e. religion of the Malians. The adherents of the Islamic faith are called Musulumi in Yoruba to correspond to Muslim, the Arabic word for an adherent of Islam having as the active participle of the same verb form, and means "submitter (to Allah)" or a nominal and active participle of Islam derivative of "Salaam" i.e. (Religion of) Peace. Islam was practiced in Yorubaland so early on in history, that a sizable proportion of Yoruba slaves taken to the Americas were already Muslim.[73] Some of these Yoruba Muslims would later stage the Malê Revolt (or The Great Revolt), which was the most significant slave rebellion in Brazil. On a Sunday during Ramadan in January 1835, in the city of Salvador, Bahia, a small group of slaves and freedmen, inspired by Muslim teachers, rose up against the government. Muslims were called Malê in Bahia at this time, from Yoruba Imale that designated a Yoruba Muslim. The Mosque served the spiritual needs of Muslims living in Ọyọ. Progressively, Islam started to gain a foothold in Yorubaland, and Muslims started building mosques. Iwo led, its first mosque built in 1655,[74] followed by Iseyin in 1760,[74] Eko/Lagos in 1774,[74] Shaki in 1790,[74] and Osogbo in 1889. In time, Islam spread to other towns like Oyo (the first Oyo convert was Solagberu), Ibadan, Abẹokuta, Ijebu Ode, Ikirun, and Ede. All of these cities already had sizable Muslim communities before the 19th century Sokoto jihad.[75] Several factors contributed to the rise of Islam in Yorubaland by the middle of the 19th century. Before the decline of Ọyọ, several towns around it had large Muslim communities, however, when Ọyọ was destroyed, these Muslims (Yorubas and immigrants) relocated to newly formed towns and villages and became Islam evangelists.

Secondly, there was a mass movement of people at this time into Yorubaland, many of these immigrants were Muslims who introduced Islam to their hosts. According to Eades, the religion "differed in attraction" and "better adapted to Yoruba social structure, because it permitted polygamy", which was already a feature of various African societies; more influential Yorubas (like Seriki Kuku of Ijebuland) soon became Muslims, with a positive impact on the natives. Islam came to Lagos at about the same time as other Yoruba towns, however, it received royal support from Ọba Kosọkọ, after he came back from exile in Ẹpẹ. Islam, like Christianity, also found common ground with the natives who already believed in a Supreme Being Olodumare / Olorun. Without delay, Islamic scholars and local Imams started establishing Koranic centers to teach Arabic and Islamic studies, much later, conventional schools were established to educate new converts and to propagate Islam. Today, the Yorubas constitute the second largest Muslim group in Nigeria, after the Hausa people of the Northern provinces. They are mostly Sunni Muslims, with small Ahmadiyya communities.

Traditional art and architecture

.jpg)

Medieval Yoruba settlements were surrounded with massive mud walls.[76] Yoruba buildings had similar plans to the Ashanti shrines, but with verandahs around the court. The wall materials comprised puddled mud and palm oil[77] while roofing materials ranged from thatches to aluminium and corrugated iron sheets.[77] A famous Yoruba fortification, the Sungbo's Eredo, was the second largest wall edifice in Africa. The structure was built in the 9th, 10th and 11th centuries in honour of a traditional aristocrat, the Oloye Bilikisu Sungbo. It was made up of sprawling mud walls and the valleys that surrounded the town of Ijebu-Ode in Ogun State. Sungbo's Eredo is the largest pre-colonial monument in Africa, larger than the Great Pyramid or Great Zimbabwe.[78][79]

The Yorubas worked with a wide array of materials in their art including; bronze, leather, terracotta, ivory, textiles, copper, stone, carved wood, brass, ceramics and glass. A unique feature of Yoruba art is its striking realism that, unlike most African art, chose to create human sculptures in vividly realistic and life sized forms. The art history of the nearby Benin empire shows that there was a cross – fertilization of ideas between the neighboring Yoruba and Edo. The Benin court's brass casters learned their art from an Ife master named Iguegha, who had been sent from Ife around 1400 at the request of Benin's oba Oguola. Indeed, the earliest dated cast-brass memorial heads from Benin replicate the refined naturalism of the earlier Yoruba sculptures from Ife.[80]

.jpg)

A lot of Yoruba artwork, including staffs, court dress, and beadwork for crowns, are associated with palaces and the royal courts.[81][82][83][84] The courts also commissioned numerous architectural objects such as veranda posts, gates, and doors that are embellished with carvings. Yoruba palaces are usually built with thicker walls, are dedicated to the gods and play significant spiritual roles. Yoruba art is also manifested in shrines and masking traditions.[85] The shrines dedicated to the said gods are adorned with carvings and house an array of altar figures and other ritual paraphernalia. Masking traditions vary by region, and diverse mask types are used in various festivals and celebrations. Aspects of Yoruba traditional architecture has also found its way into the New World in the form of shotgun houses.[86][87][88][89][90][91] Today, however, Yoruba traditional architecture has been greatly influenced by modern trends.

Masquerades are an important feature of Yoruba traditional artistry. They are generally known as Egúngún, singularly as Egún. The term refers to the Yoruba masquerades connected with ancestor reverence, or to the ancestors themselves as a collective force. There are different types of which one of the most prominent is the Gelede.[92][93] An Ese Ifa (oral literature of Orunmila divination) explains the origins of Gelede as beginning with Yemoja, the Mother of all the orisa and all living things. Yemoja could not have children and consulted an Ifa oracle, and the priest advised her to offer sacrifices and to dance with wooden images on her head and metal anklets on her feet. After performing this ritual, she became pregnant. Her first child was a boy, nicknamed "Efe" (the humorist/joker); the Efe mask emphasizes song and jests because of the personality of its namesake. Yemoja's second child was a girl, nicknamed "Gelede" because she was obese like her mother. Also like her mother, Gelede loved dancing.

After getting married themselves, neither Gelede or Efe's partner could have children. The Ifa oracle suggested they try the same ritual that had worked for their mother. No sooner than Efe and Gelede performed these rituals – dancing with wooden images on their heads and metal anklets on their feet – they started having children. These rituals developed into the Gelede masked dance and were perpetuated by the descendants of Efe and Gelede. This narrative is one of many stories that explains the origin of Gelede. An old theory stated that the beginning of Gelede might be associated with the change from a matriarchal to a patriarchal society among the Yoruba people.[94]

The Gelede spectacle and the Ifa divination system represent two of Nigeria's only three pieces on the United Nations Oral and Intangible Heritages of Humanity list, as well as the only such cultural heritage from Benin and Togo.

Festivals

One of the first observations of first time visitors to Yorubaland is the rich, exuberant and ceremonial nature of their culture, which is made even more visible by the urbanized structures of Yoruba settlements. These occasions are avenues to experience the richness of the Yoruba culture. Traditional musicians are always on hand to grace the occasions with heavy rhythms and extremely advanced percussion, which the Yorubas are well known for all over the world.[95] Praise singers and griots are there to add their historical insight to the meaning and significance of the ceremony, and of course the varieties of colorful dresses and attires worn by the people, attest to the aesthetic sense of the average Yoruba.

The Yoruba are a very expressive people who celebrate major events with colorful festivals and celebrations (Ayeye). Some of these festivals (about thirteen principal ones)[96] are secular and only mark achievements and milestones in the achievement of mankind. These include wedding ceremonies (Ìgbéyàwó), naming ceremonies (Ìsomolórúko), funerals (Ìsìnkú), housewarming (Ìsílé), New-Yam festival (Ìjesu), Odon itsu in Atakpame, Harvest ceremonies (Ìkórè), birth (Ìbí), chieftaincy (Ìjòyè) and so on.[94] Others have a more spiritual connotation, such as the various days and celebrations dedicated to specific Orisha like the Ogun day (Ojó Ògún) or the Osun festival, which is usually done at the Osun-Osogbo sacred grove located on the banks of the Osun river and around the ancient town of Osogbo.[97] The festival is dedicated to the river goddess Osun, which is usually celebrated in the month of August (Osù Ògùn) yearly. The festival attracts thousands of Osun worshippers from all over Yorubaland and the Yoruba diaspora in the Americas, spectators and tourists from all walks of life. The Osun-Osogbo Festival is a two-week-long programme. It starts with the traditional cleansing of the town called 'Iwopopo', which is then followed in three days by the lighting of the 500-year-old sixteen-point lamp called Ina Olojumerindinlogun, which literally means The sixteen eyed fire. The lighting of this sacred lamp heralds the beginning of the Osun festival. Then comes the 'Ibroriade', an assemblage of the crowns of the past ruler, the Ataoja of Osogbo, for blessings. This event is led by the sitting Ataoja of Osogbo and the Arugba Yeye Osun (who is usually a young virgin from the royal family dressed in white), who carries a sacred white calabash that contains propitiation materials meant for the goddess Osun. She is also accompanied by a committee of priestesses.[98][99] A similar event holds in the New World as Odunde Festival.[100][101]

Another very popular festival with spiritual connotations is the Eyo Olokun festival or Adamu Orisha play, celebrated by the people of Lagos. The Eyo festival is a dedication to the god of the Sea Olokun, who is an Orisha, and whose name literally mean Owner of the Seas.[96] Generally, there is no customarily defined time for the staging of the Eyo Festival. This leads to a building anticipation as to what date would be decided upon. Once a date for its performance is selected and announced, the festival preparations begin. It encompasses a week-long series of activities, and culminates in a striking procession of thousands of men clothed in white and wearing a variety of coloured hats, called Aga. The procession moves through Lagos Island Isale Eko, which is the historical centre of the Lagos metropolis. On the streets, they move through various crucial locations and landmarks in the city, including the palace of the traditional ruler of Lagos, the Oba, known as the Iga Idunganran. The festival starts from dusk to dawn, and has been held on Saturdays (Ojó Àbáméta) from time immemorial. A full week before the festival (always a Sunday), the 'senior' Eyo group, the Adimu (identified by a black, broad-rimmed hat), goes public with a staff. When this happens, it means the event will take place on the following Saturday. Each of the four other 'important' groups – Laba (Red), Oniko (yellow), Ologede (Green) and Agere (Purple) — take their turns in that order from Monday to Thursday.

The Eyo masquerade essentially admits tall people, which is why it is described as Agogoro Eyo (literally meaning the tall Eyo masquerade). In the manner of a spirit (An Orisha) visiting the earth on a purpose, the Eyo masquerade speaks in a ventriloquial voice, suggestive of its otherworldliness; and when greeted, it replies: Mo yo fun e, mo yo fun ara mi, which in Yoruba means: I rejoice for you, and I rejoice for myself. This response connotes the masquerades as rejoicing with the person greeting it for the witnessing of the day, and its own joy at taking the hallowed responsibility of cleansing. During the festival, Sandals and foot wear, as well as Suku, a hairstyle that is popular among the Yorubas – one that has the hair converge at the middle, then shoot upward, before tipping downward – are prohibited. The festival has also taken a more touristic dimension in recent times, which like the Osun Osogbo festival, attracts visitors from all across Nigeria, as well as Yoruba diaspora populations. In fact, it is widely believed that the play is one of the manifestations of the customary African revelry that serves as the forerunner of the modern carnival in Brazil and other parts of the New World, which may have been started by the Yoruba slaves transplanted in that part of the world due to the Atlantic slave trade.[102][103][104][105]

Music

The music of the Yoruba people is perhaps best known for an extremely advanced drumming tradition,[106] especially using the dundun[107] hourglass tension drums. The representation of musical instruments on sculptural works from Ile-Ife, indicates, in general terms a substantial accord with oral traditions. A lot of these musical instruments date back to the classical period of Ile-Ife, which began at around the 10th century A.D. Some were already present prior to this period, while others were created later. The hourglass tension drum (Dùndún) for example, may have been introduced around the 15th century (1400s), the Benin bronze plaques of the middle period depicts them. Others like the double and single iron clapper-less bells are examples of instruments that preceded classical Ife.[108] Yoruba folk music became perhaps the most prominent kind of West African music in Afro-Latin and Caribbean musical styles. Yoruba music left an especially important influence on the music of Trinidad, the Lukumi religious traditions,[109] Capoeira practice in Brazil and the music of Cuba.[110]

Yoruba drums typically belong to four major families, which are used depending on the context or genre where they are played. The Dùndún / Gángan family, is the class of hourglass shaped talking drums, which imitate the sound of Yoruba speech. This is possible because the Yoruba language is tonal in nature. It is the most common and is present in many Yoruba traditions, such as Apala, Jùjú, Sekere and Afrobeat. The second is the Sakara family. Typically, they played a ceremonial role in royal settings, weddings and Oríkì recitation; it is predominantly found in traditions such as Sakara music, Were and Fuji music. The Gbedu family (literally, "large drum") is used by secret fraternities such as the Ogboni and royal courts. Historically, only the Oba might dance to the music of the drum. If anyone else used the drum they were arrested for sedition of royal authority. The Gbèdu are conga shaped drums played while they sit on the ground. Akuba drums (a trio of smaller conga-like drums related to the gbèdu) are typically used in afrobeat. The Ogido is a cousin of the gbedu. It is also shaped like a conga but with a wider array of sounds and a bigger body. It also has a much deeper sound than the conga. It is sometimes referred to as the "bass drum". Both hands play directly on the Ogido drum.[111]

Today, the word Gbedu has also come to be used to describe forms of Nigerian Afrobeat and Hip Hop music. The fourth major family of Yoruba drums is the Bàtá family, which are well-decorated double-faced drums, with various tones. They were historically played in sacred rituals. They are believed to have been introduced by Shango, an Orisha, during his earthly incarnation as a warrior king.

Traditional Yoruba drummers are known as Àyán. The Yoruba believe that Àyángalú was the first drummer. He is also believed to be the spirit or muse that inspires drummers during renditions. This is why some Yoruba family names contain the prefix 'Ayan-' such as Ayangbade, Ayantunde, Ayanwande.[112] Ensembles using the dundun play a type of music that is also called dundun.[107] The Ashiko (Cone shaped drums), Igbin, Gudugudu (Kettledrums in the Dùndún family), Agidigbo and Bèmbé are other drums of importance. The leader of a dundun ensemble is the oniyalu meaning; ' Owner of the mother drum ', who uses the drum to "talk" by imitating the tonality of Yoruba. Much of this music is spiritual in nature, and is often devoted to the Orisas.

Within each drum family there are different sizes and roles; the lead drum in each family is called Ìyá or Ìyá Ìlù, which means "Mother drum", while the supporting drums are termed Omele. Yoruba drumming exemplifies West-African cross-rhythms and is considered to be one of the most advanced drumming traditions in the world. Generally, improvisation is restricted to master drummers. Some other instruments found in Yoruba music include, but are not limited to; The Gòjé (violin), Shèkèrè (gourd rattle), Agidigbo (thumb piano that takes the shape of a plucked Lamellophone), Saworo (metal rattles for the arm and ankles, also used on the rim of the bata drum), Fèrè (whistles), Aro (Cymbal)s, Agogô (bell), different types of flutes include the Ekutu, Okinkin and Igba.

Oriki (or praise singing), a genre of sung poetry that contains a series of proverbial phrases, praising or characterizing the respective person is of Egba and Ekiti origin, is often considered the oldest Yoruba musical tradition. Yoruba music is typically Polyrhythmic, which can be described as interlocking sets of rhythms that fit together somewhat like the pieces in a jigsaw puzzle. There is a basic timeline and each instrument plays a pattern in relation to that timeline. The resulting ensemble provides the typical sound of West African Yoruba drumming. Yoruba music is a component of the modern Nigerian popular music scene. Although traditional Yoruba music was not influenced by foreign music, the same cannot be said of modern-day Yoruba music, which has evolved and adapted itself through contact with foreign instruments, talent, and creativity.

Twins in Yoruba society

The Yoruba present the highest dizygotic twinning rate in the world (4.4% of all maternities).[11][113] They manifest at 45–50 twin sets (or 90–100 twins) per 1,000 live births, possibly because of high consumption of a specific type of yam containing a natural phytoestrogen that may stimulate the ovaries to release an egg from each side.

Twins are very important for the Yoruba and they usually tend to give special names to each twin.[114] The first of the twins to be born is traditionally named Taiyewo or Tayewo, which means 'the first to taste the world', or the 'slave to the second twin', this is often shortened to Taiwo, Taiye or Taye. Kehinde is the name of the last born twin. Kehinde is sometimes also referred to as Kehindegbegbon, which is short for; Omo kehin de gba egbon and means, 'the child that came behind gets the rights of the elder'.

Twins are perceived as having spiritual advantages or as possessing magical powers.[115] This is different from some other cultures, which interpret twins as dangerous or unwanted.[115]

Calendar

Time is measured in "ọgán" (seconds), ìṣẹ́jú (minutes), wákàtí (hours), ọjọ́ (days), ọ̀sẹ̀ (weeks), oṣù (months) and ọdún (years). There are 60 (ọgọta) ìṣẹ́jú in 1 (okan) wákàtí; 24 (merinleogun) wákàtí in 1 (okan) ọjọ́; 7 (meje) ọjọ́ in 1 (okan) ọ̀sẹ̀; 4 (merin) ọ̀sẹ̀ in 1 (okan) oṣù and 52 (mejilelaadota) ọ̀sẹ̀ in 1 (okan)ọdún. There are 12 (mejila) oṣù in 1 ọdún.[116]

| Months in Yoruba calendar: | Months in Gregorian calendar:[117] |

|---|---|

| Ṣẹrẹ | January |

| Erélé | February |

| Erénà | March |

| Igbe | April |

| Èbìbí | May |

| Okúdù | June |

| Agẹmọ | July |

| Ògún | August |

| Owérè (Owéwè) | September |

| Ọwàrà (Owawa) | October |

| Belu | November |

| Ọ̀pẹ | December |

The Yoruba week consist of five days. Of these, only four have names. Traditionally, the Yoruba count their week starting from the Ojó Ògún, this day is dedicated to Ògún. The second day is Ojó Jákúta the day is dedicated to Sàngó. The third day is known as the Ojó Òsè- this day is dedicated to Òrìshà ńlá (Obàtálá), while the fourth day is the Ojó Awo, in honour of Òrúnmìlà.

| Yoruba calendar traditional days |

|---|

| Days: |

| Ojó Ògún (Ògún) |

| Ojó Jákúta (Shàngó) |

| Ojó Òsè (Òrìshà ńlá / Obàtálá) |

| Ojó Awo (Òrúnmìlà / Ifá) |

The Yoruba calendar (Kojoda) year starts from 3 to 2 June of the following year.[118] According to this calendar, the Gregorian year 2008 CE is the 10,050th year of Yoruba culture.[119] To reconcile with the Gregorian calendar, Yoruba people also often measure time in seven days a week and four weeks a month:

| Modified days in Yoruba calendar | Days in Gregorian calendar |

|---|---|

| Ọjọ́-Àìkú | Sunday |

| Ọjọ́-Ajé | Monday |

| Ọjọ́-Ìṣẹ́gun | Tuesday |

| Ọjọ́-'Rú | Wednesday |

| Ọjọ́-Bọ̀ | Thursday |

| Ọjọ́-Ẹtì | Friday |

| Ọjọ́-Àbámẹ́ta | Saturday[120] |

Cuisine

Solid food, mostly cooked, pounded or prepared with hot water are basic staple foods of the Yoruba. These foods are all by-products of crops like cassava, yams, cocoyam and forms a huge chunk of it all. Others like Plantain, corn, beans, meat, and fish are also chief choices.[121]

Some common Yoruba foods are iyan (pounded yam), Amala, eba, semo, fufu, Moin moin (bean cake) and akara.[94] Soups include egusi, ewedu, okra, vegetables are also very common as part of diet. Items like rice and beans (locally called ewa) are part of the regular diet. Some dishes are also prepared for festivities and ceremonies such as Jollof rice and Fried rice. Other popular dishes are Ekuru, stews, corn, cassava and flours – e.g. maize, yam, plantain and beans, eggs, chicken, beef and assorted forms of meat (ponmo is made from cow skin). Some less well known meals and many miscellaneous staples are arrowroot gruel, sweetmeats, fritters and coconut concoctions; and some breads – yeast bread, rock buns, and palm wine bread to name a few.[121]

- Yoruba cultural dishes

Amala is a Yoruba food

Amala is a Yoruba food Akara is a Yoruba bean fritter

Akara is a Yoruba bean fritter Ofada rice is a Yoruba dish

Ofada rice is a Yoruba dish Ofada rice is traditionally in a leaf

Ofada rice is traditionally in a leaf Moin Moin is a Yoruba steamed bean pudding

Moin Moin is a Yoruba steamed bean pudding A collection of foods eaten by Yorubas in general

A collection of foods eaten by Yorubas in general

Dressing and clothing

The Yoruba take immense pride in their attire, for which they are well known.Clothing materials traditionally come from processed cotton by traditional weavers.They also believe that the type of clothes worn by a man depicts his personality and social status, and that different occasions require different clothing outfits.

Typically, the Yoruba have a very wide range of materials used to make clothing, the most basic being the Aṣo-Oke, which is a hand loomed cloth of different patterns and colors sewn into various styles.[122] and which comes in very many different colors and patterns. Aso Oke comes in three major styles based on pattern and coloration;

- Alaari – a rich red Aṣọ-Oke,

- Sanyan – a brown and usual light brown Aṣọ-Oke, and

- Ẹtu – a dark blue Aṣọ-Oke.

Other clothing materials include but are not limited to:

- Ofi – pure white yarned cloths, used as cover cloth, it can be sewn and worn.

- Aran – a velvet clothing material of silky texture sewn into Danṣiki and Kẹmbẹ, worn by the rich.

- Adirẹ – cloth with various patterns and designs, dye in indigo ink (Ẹlu or Aro).

Clothing in Yoruba culture is gender sensitive, despite a tradition of non-gender conforming families. For menswear, they have Bùbá, Esiki and Sapara, which are regarded as Èwù Àwòtélè or underwear, while they also have Dandogo, Agbádá, Gbariye, Sulia and Oyala, which are also known as Èwù Àwòlékè / Àwòsókè or overwear. Some fashionable men may add an accessory to the Agbádá outfit in the form of a wraparound (Ìbora).[123][124]

They also have various types of Sòkòtò or native trousers that are sewn alongside the above-mentioned dresses. Some of these are Kèmbè (Three-Quarter baggy pants), Gbáanu, Sóóró (Long slim / streamlined pants), Káamu and Sòkòtò Elemu. A man's dressing is considered incomplete without a cap (Fìlà). Some of these caps include, but are not limited to, Gobi (Cylindrical, which when worn may be compressed and shaped forward, sideways, or backward), Tinko, Abetí-ajá (Crest-like shape that derives its name from its hanging flaps that resembles a dog's hanging ears. The flaps can be lowered to cover the ears in cold weather, otherwise, they are upwardly turned in normal weather), Alagbaa, Oribi, Bentigoo, Onide, and Labankada (a bigger version of the Abetí-ajá, and is worn in such a way as to reveal the contrasting color of the cloth used as underlay for the flaps).

Women also have different types of dresses. The most commonly worn are Ìró (wrapper) and Bùbá (blouse-like loose top). Women also have matching Gèlè (head gear) that must be put on whenever the Ìró and Bùbá is on. Just as the cap (Fìlà) is important to men, women's dressing is considered incomplete without Gèlè. It may be of plain cloth or costly as the women can afford. Apart from this, they also have ìborùn (Shawl) and Ìpèlé (which are long pieces of fabric that usually hang on the left shoulder and stretch from the hind of the body to the fore). At times, it is tied round their waists over the original one piece wrapper. Unlike men, women have two types of under wears (Èwù Àwòtélè), called; Tòbi and Sinmí. Tòbi is like the modern day apron with strings and spaces in which women can keep their valuables. They tie the tòbi around the waists before putting on the Ìró (wrapper). Sinmí is like a sleeveless T-shirt that is worn under before wearing any other dress on the upper body.

There are many types of beads (Ìlèkè), hand laces, necklaces (Egba orùn), anklets (Egba esè) and bangles (Egba owó) that are used in Yorubaland. These are used by both males and females, and are put on for bodily adornment. Chiefs, priests, kings or people of royal descent, especially use some of these beads as a signifier of rank. Some of these beads include Iyun, Lagidigba, Àkún etc. An accessory especially popular among royalty and titled Babalawos / Babalorishas is the Ìrùkèrè, which is an artistically processed animal tail, a type of Fly-whisk. The horsetail whiskers are symbols of authority and stateliness. It can be used in a shrine for decoration but most often is used by chief priests and priestesses as a symbol of their authority or Ashe.[125] As most men go about with their hair lowly cut or neatly shaven, the reverse is the case for women. Hair is considered the ' Glory of the woman '. They usually take care of their hair in two major ways; They plait and they weave. There are many types of plaiting styles, and women readily pick any type they want. Some of these include kòlésè, Ìpàkó-elédè, Sùkú, Kojúsóko, Alágogo, Konkoso, Etc. Traditionally, The Yoruba consider tribal marks ways of adding beauty to the face of individuals. This is apart from the fact that they show clearly from which part of Yorubaland an individual comes from, since different areas are associated with different marks. Different types of tribal marks are made with local blades or knives on the cheeks. These are usually done at infancy, when children are not pain conscious. Some of these tribal marks include Pélé, Abàjà-Ègbá, Abàjà-Òwu, Abàjà-mérin, Kéké, Gòmbò, Ture, Pélé Ifè, Kéké Òwu, Pélé Ìjèbú etc. This practice is near extinct today.[126]

The Yoruba believe that development of a nation is akin to the development of a man or woman. Therefore, the personality of an individual has to be developed in order to fulfill his or her responsibilities. Clothing among the Yoruba people is a crucial factor upon which the personality of an individual is anchored. This belief is anchored in Yoruba proverbs. Different occasions also require different outfits among the Yoruba.[127]

Demographics

Benin

Estimates of the Yoruba in Benin vary from around 1.1 to 1.5 million people. The Yoruba are the main group in the Benin department of Ouémé, all Subprefectures including Porto Novo (Ajasè), Adjara; Collines Province, all subprefectures including Savè, Dassa-Zoume, Bante, Tchetti, Gouka; Plateau Province, all Subprefectures including Kétou, Sakété, Pobè; Borgou Province, Tchaourou Subprefecture including Tchaourou; Zou Province, Ouihni and Zogbodome Subprefecture; Donga Province, Bassila Subprefecture and Alibori, Kandi Subprefecture.[128]

- Places

The chief Yoruba cities or towns in Benin are: Porto-Novo (Ajase), Ouèssè (Wese), Ketu, Savé (Tchabe), Tchaourou (Shaworo), Bantè-Akpassi, Bassila, Ouinhi, Adjarra, Adja-Ouèrè (Aja Were), Sakété (Itakete), Ifangni (Ifonyi), Pobè, Dassa (Idasha), Glazoue (Gbomina), Ipinle, Aledjo-Koura etc.[129]

West Africa (other)

The Yoruba in Burkina Faso are numbered around 70,000 people, and around 60,000 in Niger. In the Ivory Coast, they are concentrated in the cities of Abidjan (Treichville, Adjamé), Bouake, Korhogo, Grand Bassam and Gagnoa where they are mostly employed in retail at major markets.[130][131] Otherwise known as "Anago traders", they dominate certain sectors of the retail economy.

Nigeria

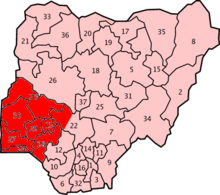

The Yorubas are the main ethnic groups in the Nigerian federal states of Ekiti, Lagos, Ogun, Ondo, Osun, Kwara, Oyo, the western third of Kogi and the Akoko parts of Edo.[132]

- Places

The chief Yoruba cities or towns in Nigeria are: Abẹokuta, Abigi, Ado-Ekiti, Agbaja, Ago iwoye,[Ago Are,Oyo],[Agunrege,Oyo],[Ajase ipo, Akungba-akoko, Akurẹ, Atan-otta,[Afijio,Aawe,Oyo], Ayetoro, Ayetoro gbede, Badagry, Ede, Efon-alaaye, Egbe,Egi oyo-ippo, Ejigbo, Emure-ekiti, Epe, Eruwa, Esa-oke, Esie, Fiditi,[Gbaja,Igbomina], Gbongan, Ibadan, Ibokun, Idanre, Idi-iroko, Ido-ani, Ido-ekiti, Ifo, Ifon (Ondo), Ifon Osun, Igangan, Iganna, Igbeti, Igboho, Igbo-ora, Ijẹbu-igbo, Ijebu-Ijesha, Ijebu Ode, Ijede, Ijero-ekiti, Ijoko, Ikare-akoko, Ikenne, Ikere-Ekiti, Ikire, Ikirun, Ikole-ekiti, Ikorodu, Ila-orangun, Ilaje, Ilaro, Ilawe-ekiti, Ilé-Ifẹ, Ile-oluji, Ilesa, Illah Bunu, Ilobu, Ilọrin,[Iludun,Kwara State] Imeko, Imota, Inisa, Iperu, Ipetu-Ijesha, Ipetumodu, Iragbiji, Iree,[Iwoye,Oyo], Isanlu, Ise-ekiti, Iseyin, Iwo, Iyara, Jebba, Kabba, Kishi, Lagos (Eko), Lalupon,[Lanlate,Oyo State] Lokoja, Mopa, Obajana, Ode-Irele, Ode-omu, Ore, Odogbolu, Offa, Ogbomoso, Ogere-remo, Ogidi-ijumu, Oka-akoko, Okeho,[Oke Ode,Kwara State] Okitipupa, Okuku, Omu Aran, Omuo, Ondo City (Ode Ondo),[Oru Ago,Kwara State] Osogbo, {Otun-Oro,Kwara State,}Sango-otta, Owode, Otun-ekiti,Osi[Kwara State], Owo, Ọyọ, Shagamu, Shaki, Share, Tede, Upele, Usi-ekiti, Modakeke, Ijare,, Oke-Igbo, Ifetedo, Osu, Edun-Abon, Isharun, Aaye,.

Togo

Estimates of the Yoruba in Togo vary from around 500,000 to 600,000 people. There are both immigrant Yoruba communities from Nigeria, and indigenous ancestral Yoruba communities living in Togo. Footballer Emmanuel Adebayor is an example of a Togolese from an immigrant Yoruba background. Indigenous Yoruba communities in Togo, however can be found in the Togolese departments of Plateaux Region, Anie, Ogou and Est-Mono prefectures; Centrale Region and Tchamba Prefecture. The chief Yoruba cities or towns in Togo are: Atakpame, Anié, Morita, Ofe, Elavagnon, Kambole.

The Yoruba diaspora

.jpg)

Yoruba people or descendants can be found all over the world especially in the United Kingdom, Canada, the United States, Cuba, Brazil, Latin America, and the Caribbean.[134][135][136][137] Significant Yoruba communities can be found in South America and Australia. The migration of Yoruba people all over the world has led to a spread of the Yoruba culture across the globe. Yoruba people have historically been spread around the globe by the combined forces of the Atlantic slave trade[138][139][140][141] and voluntary self migration.[142] Their exact population outside Africa is unknown, but researchers have established that the majority of the African component in the ancestry of African Americans is of Yoruba and/or Yoruba-like extraction.[143][144][145][146][147][148] In their Atlantic world domains, the Yorubas were known by the designations: "Nagos/Anago", "Terranova", "Lucumi" and "Aku", or by the names of their various clans.

The Yoruba left an important presence in Cuba and Brazil,[149] particularly in Havana and Bahia.[150] According to a 19th-century report, "the Yoruba are, still today, the most numerous and influential in this state of Bahia.[151][152][153][154] The most numerous are those from Oyo, capital of the Yoruba kingdom".[155][156] Others included Ijexa (Ijesha), Lucumi Ota (Aworis), Ketus, Ekitis, Jebus (Ijebu), Egba, Lucumi Ecumacho (Ogbomosho), and Anagos. In the documents dating from 1816 to 1850, Yorubas constituted 69.1% of all slaves whose ethnic origins were known, constituting 82.3% of all slaves from the Bight of Benin. The proportion of slaves from West-Central Africa (Angola – Congo) dropped drastically to just 14.7%.[157]

.png)

Between 1831 and 1852 the African-born slave and free population of Salvador, Bahia surpassed that of free Brazil born Creoles. Meanwhile, between 1808 and 1842 an average of 31.3% of African-born freed persons had been Nagos (Yoruba). Between 1851 and 1884, the number had risen to a dramatic 73.9%.

Other areas that received a significant number of Yoruba people and are sites of Yoruba influence are: Puerto Rico, Saint Lucia, Grenada, Santa Margarita and Belize, British Guyana, Saint-Domingue (Now Haiti), Jamaica[158](Where they settled and established such places as Abeokuta, Naggo head in Portmore, and by their hundreds in other parishes like Hanover and Westmoreland, both in western Jamaica- leaving behind practices such as Ettu from Etutu, the Yoruba ceremony of atonement among other customs of people bearing the same name, and certain aspects of Kumina such as Sango veneration),[159][160][161][162][163][164][165] Barbados, Dominican republic, Montserrat, etc.

On 31 July 2020, the Yoruba World Congress joined the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO).[166][167]

Genetics

Genetic studies have shown the Yoruba to cluster most closely with other West African peoples.[168]

Notable people of Yoruba origin

References

- Atlas, World. "Largest Ethnic Groups In Nigeria". Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- "Bénin". www.axl.cefan.ulaval.ca.

- "Ethnic groups of Ghana, 1.6% of The Ghanaian national population". Université Laval,QC, Canada. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- "Ethnic groups of Togo. 1.8% of The Togolese population is Ifè, a Yoruboid sub-group based around east-central Togo, 0.7% is Kambole, a Yoruba group based in Kambole town, while another 1.4% is 'Yoruba proper' totalling 3.9% of Togolese national population being Yoruba and(or) Yorurboid". Université Laval,QC, Canada. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- "Ethnologue, Languages of Côte D'Ivoire. 115,000 Yoruba speakers: LeClerc (2017), Dispersed". Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- "Ethnic groups of Cote D'Ivoire". Université Laval,QC, Canada. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- Nolte, Insa; Jones, Rebecca; Taiyari, Khadijeh; Occhiali, Giovanni (July 2016). "Research note: Exploring survey data for historical and anthropological research: Muslim–Christian relations in south-west Nigeria". African Affairs. 115 (460): 541–561. doi:10.1093/afraf/adw035.

- Atlas, World. "Largest Ethnic Groups In Nigeria". Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- John T. Bendor-Samuel. "Benue-Congo languages". Encyclopaedeia Britannica.

- Jacob Oluwatayo Adeuyan (12 October 2011). Contributions of Yoruba people in the Economic & Political Developments of Nigeria. Authorhouse. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-4670-2480-8.

- Leroy Fernand; Olaleye-Oruene Taiwo; Koeppen-Schomerus Gesina; Bryan Elizabeth (2002). "Yoruba Customs and Beliefs Pertaining to Twins". Twin Research. 5 (2): 132–136. doi:10.1375/1369052023009. PMID 11931691.

- Jeremy Seymour Eades (1994). Strangers and Traders: Yoruba Migrants, Markets, and the State in Northern Ghana Volume 11 of International African library. Africa World Press. ISBN 978-0-86543-419-6. ISSN 0951-1377.

- "Ivory Coast country profile". BBC News. 15 January 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- National African Language Resource Center. "Yoruba" (PDF). Indiana University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- Akinrinade and Ogen, Sola and Olukoya (2011). "Historicising the Nigerian Diaspora: Nigerian Migrants and Homeland Relations" (PDF). Turkish Journal of Politics. 2:2: 15 – via https://scinapse.io/papers/2183612463.

- Clapperton, Hugh; Lander, Richard (1829).

- Maureen Warner-Lewis (1997). Trinidad Yoruba: From Mother Tongue to Memory. University of the West Indies. p. 20. ISBN 978-976-640-054-5.

- Jorge Canizares-Esguerra; Matt D. Childs; James Sidbury (2013). The Black Urban Atlantic in the Age of the Slave Trade. The Early Modern Americas. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-0813-9.

- Toyin Falola; Ann Genova (2005). Orisa: Yoruba gods and spiritual identity in Africa and the diaspora. Africa World Press. ISBN 978-1-59221-373-3.

- SimonMary A. Aihiokhai. "Ancestorhood in Yoruba Religion and Sainthood in Christianity: Envisioning an Ecological Awareness and Responsibility" (PDF). p. 2. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- Olumbe Bassir (21 August 2012). "Marriage Rites among the Aku (Yoruba) of Freetown". Africa. 24 (3): 251–256. doi:10.2307/1156429. JSTOR 1156429.

- The number of speakers of Yoruba was estimated at around 20 million people in the 1990s. No reliable estimate of more recent date is known. Metzler Lexikon Sprache (4th ed. 2010) estimates roughly 30 million based on population growth figures during the 1990s and 2000s. The population of Nigeria (where the majority of Yoruba live) has grown by 44% between 1995 and 2010, so that the Metzler estimate for 2010 appears plausible.

- This widely followed classification is based on Adetugbọ's (1982) dialectological study – the classification originated in his 1967 PhD thesis The Yoruba Language in Western Nigeria: Its Major Dialect Areas, ProQuest 288034744. See also Adetugbọ (1973). "The Yoruba Language in Yoruba History". In Biobaku, Saburi O. (ed.). Sources of Yoruba History. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 183–193. ISBN 0-19-821669-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Adetugbọ 1973, pp. 192–3. (See also the section Dialects.)

- Adetugbọ 1973, p. 185

- "Ile-Ife | Nigeria". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- Ojuade, J. 'Sina. "THE ISSUE OF 'ODUDUWA' IN YORUBA GENESIS: THE MYTHS AND REALITIES". Transafrican Journal of History, vol. 21, 1992, pp. 139–158. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24520425.

- Adeyemi, A. (18 April 2016). "Migration and the Yorùbá Myth of Origin". European Journal of Arts: 36–45. doi:10.20534/eja-16-1-36-45. ISSN 2310-5666.

- Robin Walker (2006). When We Ruled: The Ancient and Mediœval History of Black Civilisations. Every Generation Media (Indiana University). p. 323. ISBN 978-0-9551068-0-4.

- Alice Bellagamba; Sandra E. Greene; Martin A. Klein (2013). African Voices on Slavery and the Slave Trade: Volume 1, The Sources. Cambridge University Press. pp. 150, 151. ISBN 978-0-521-19470-9.

- Falola, Toyin, "The Yorùbá Nation", Yorùbá Identity and Power Politics, Boydell and Brewer Limited, pp. 29–48, ISBN 978-1-58046-662-2, retrieved 26 May 2020

- Ajayi, Timothy Temilola (2001). ASPECT IN YORUBA AND NIGERIAN ENGLISH. Internet Archive (PH.D thesis). University of Florida. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- Blier, Suzanne Preston (2015). Art and Risk in Ancient Yoruba: Ife History, Politics, and Identity c. 1300. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-02166-2.

- Kevin Shillington (22 November 2004). "Ife, Oyo, Yoruba, Ancient:Kingdom and Art". Encyclopedia of African History. Routledge. p. 672. ISBN 978-1-57958-245-6. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- Laitin, David D. (1986). Hegemony and culture: politics and religious change among the Yoruba. University of Chicago Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-226-46790-0.

- Encarta.msn.com

- L. J. Munoz (2003). A Living Tradition: Studies on Yoruba Civilisation. Bookcraft (the University of Michigan). ISBN 978-978-2030-71-9.

- MacDonald, Fiona; Paren, Elizabeth; Shillington, Kevin; Stacey, Gillian; Steele, Philip (2000). Peoples of Africa, Volume 1. Marshall Cavendish. p. 385. ISBN 978-0-7614-7158-5.

- Oyo Empire at Britannica.com

- Domingues da Silva, Daniel B.; Misevich, Philip (20 November 2018), "Atlantic Slavery and the Slave Trade: History and Historiography", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-027773-4, retrieved 26 May 2020

- Thornton, John (1998). Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800 (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 122, 304–311.

- Alpern, Stanley B. (1998). Amazons of Black Sparta: The Women Warriors of Dahomey. New York University Press. p. 34.

- "The Dispersal of the Yoruba People", The Development of Yoruba Candomble Communities in Salvador, Bahia, 1835-1986, Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-1-137-48643-1, retrieved 26 May 2020

- Historical Society of Nigeria (1978). Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria (Volume 9, Issues 2–4). The Society (Indiana University).

- Earl Phillips (1969). "The Egba at Abeokuta: Acculturation and Political change, 1830–1870". Journal of African History. 10 (1): 117–131. doi:10.1017/s0021853700009312. JSTOR 180299.

- Jacob Oluwatayo Adeuyan (12 October 2011). Contributions of Yoruba People in the Economic & Political Developments of Nigeria. AuthorHouse, 2011. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-4670-2480-8.

- ABC-Clio Information Services (1985). Africa since 1914: a historical bibliography. 17. ABC-Clio Information Services. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-87436-395-1.

- Niara Sudarkasa (1973). Where Women Work: A Study of Yoruba Women in the Marketplace and in the Home, Issues 53-56 of Anthropological papers. University of Michigan. pp. 59–63.

- "Brooklyn Museum". www.brooklynmuseum.org.

- A. Adelusi-Adeluyi and L. Bigon (2014) "City Planning: Yoruba City Planning" in Springer's Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures (third edition), ed. by Helaine Selin.

- Bolaji Campbell; R. I. Ibigbami (1993). Diversity of Creativity in Nigeria: A Critical Selection from the Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on the Diversity of Creativity in Nigeria. Department of Fine Arts, Obafemi Awolowo University. p. 309. ISBN 9789783207806.

- Peter Blunt; Dennis M. Warren; Norman Thomas Uphoff (1996). Indigenous Organizations and Development Higher Education Policy Series (IT studies in indigenous knowledge and development). Intermediate Technology Publications. ISBN 978-1-85339-321-1.

- Diedrich Westermann; Edwin William Smith; Cyril Daryll Forde (1998). "Africa, Volume 68, Issues 3-4". International African Institute, International Institut: 364. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - American Anthropological Association (1944). Memoirs of the American Anthropological Association, Issues 63–68.

- Aderibigbe, Gbola, editor. Medine, Carolyn M. Jones, editor. Contemporary perspectives on religions in Africa and the African diaspora. ISBN 978-1-137-50051-9. OCLC 1034928481.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Lillian Trager (January 2001). Yoruba Hometowns: Community, Identity, and Development in Nigeria. Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-55587-981-5. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- Abimbola, Kola (2005). Yoruba Culture: A Philosophical Account (Paperback ed.). Iroko Academics Publishers. ISBN 978-1-905388-00-4.

- Abimbola, Kola (2006). Yoruba Culture: A Philosophical Account. iroko academic publishers. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-905388-00-4. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- Imo, Dara. Connecting African art collectors with dealers, based on a foundation of knowledge about the origin, use & distinguishing features of listed pieces./

- Bascom, William Russell (1969). Ifa Divination: Communication Between Gods and Men in West Africa. Indiana University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-253-20638-1. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- Kevin Baxter (on De La Torre), "Ozzie Guillen secure in his faith", Los Angeles Times, 2007

- Article: Oduduwa, The Ancestor Of The Crowned Yoruba Kings Archived 5 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Who are the Yoruba!". Archived from the original on 2 July 2011. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- John O. Hunwick (1992). Religion and National Integration in Africa: Islam, Christianity, and Politics in the Sudan and Nigeria (Series in Islam and society in Africa). Northwestern University Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-8101-1037-3.

- Dr Donald R Wehrs (2013). Pre-Colonial Africa in Colonial African Narratives: From Ethiopia Unbound to Things Fall Apart, 1911–1958. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4094-7495-1.

- Ádébáyò Ádésóyè (2015). Scientific Pilgrimage: 'The Life and times of Emeritus Professor V.A Oyenuga'. D.Sc, FAS, CFR Nigeria's first Emeritus Professor and Africa's first Agriculture Professor. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-5049-3785-6.

- A. I. Asiwaju (1976). Western Yorubaland under European rule, 1889–1945: a comparative analysis of French and British colonialism. European Philosophy and the Human Sciences. Humanities Press (Ibadan history series, the University of Michigan). ISBN 978-0-391-00605-8.

- Frank Leslie Cross; Elizabeth A. Livingstone (2005). The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press. p. 1162. ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3.

- Adebanwi, Wale, "Seizing the Heritage: Playing Proper Yorùbá in an Age of Uncertainty", Yorùbá Elites and Ethnic Politics in Nigeria, Cambridge University Press, pp. 224–243, ISBN 978-1-107-28625-2, retrieved 26 May 2020

- "Christianity and Islam Introduction". Yorupedia. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- "Islamic Education in Nigeria: How It All Began". Nigerian Finder.

- Mission Et Progrès Humain (Mission and Human Progress) Studia missionalia (in French). Gregorian Biblical BookShop. 1998. p. 168. ISBN 978-8-876-5278-76.

- Paul E. Lovejoy; Nicholas Rogers (2012). Unfree Labour in the Development of the Atlantic World. Routledge. p. 157. ISBN 978-1-136-30059-2.

- White, Julie (2015), "Learning in 'No Man's Land'", Interrogating Conceptions of “Vulnerable Youth” in Theory, Policy and Practice, SensePublishers, pp. 97–110, ISBN 978-94-6300-121-2, retrieved 26 May 2020

- Beek, Walter E. A. van (31 December 1988), "Purity and statecraft: the Fulani jihad and its empire", The Quest for Purity, De Gruyter, pp. 149–182, ISBN 978-3-11-086092-4, retrieved 26 May 2020

- Allen G. Noble (2007). Traditional Buildings: A Global Survey of Structural Forms and Cultural Functions Volume 11 of International Library of Human Geography. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-305-6.

- Jeremy Seymour Eades (Changing cultures) (1980). The Yoruba Today). Cambridge Latin Texts (CUP Archive). ISBN 978-0-521-22656-1.

- Molefi Kete Asante (2014). The History of Africa: The Quest for Eternal Harmony. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-01349-3.

- Peter G. Stone (2011). Cultural Heritage, Ethics and the Military Volume 4 of Heritage matters series. Boydell Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-1-84383-538-7. ISSN 1756-4832.

- "Origins and Empire: The Benin, Owo, and Ijebu Kingdoms". The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History). Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- G. J. Afolabi Ojo (1966). Yoruba palaces: a study of Afins of Yorubaland. University of Michigan.

- N Umoru-Oke (2010). "Risawe's Palace, Ilesa Nigeria: Traditional Yoruba Architecture as Socio-Cultural and Religious Symbols". African Research Review. 4 (3). doi:10.4314/afrrev.v4i3.60187.

- C. A. Brebbia (2011). The Sustainable World Volume 142 of WIT transactions on ecology and the environment. Wessex Institute of Technology (WIT Press). ISBN 978-1-84564-504-5. ISSN 1746-448X.

- Cordelia Olatokunbo Osasona (2005). Ornamentation in Yoruba folk architecture: a catalogue of architectural features, ornamental motifs and techniques. Bookbuilders Editions Africa. ISBN 978-978-8088-28-8.

- Henry John Drewal; John Pemberton; Rowland Abiodun; Allen Wardwell (1989). Yoruba: nine centuries of African art and thought. Center for African Art in Association with H.N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-1794-1.

- Patricia Lorraine Neely (2005). The Houses of Buxton: A Legacy of African Influences in Architecture. P Designs Publishing. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-9738754-1-6.

- Dell Upton; John Michael Vlach (1986). Common Places: Readings in American Vernacular Architecture. University of Georgia Press, 1986. ISBN 978-0-8203-0750-3.

- Kevin Carroll (1992). Architectures of Nigeria: Architectures of the Hausa and Yoruba Peoples and of the Many Peoples Between--tradition and Modernization. Society of African Missions. ISBN 978-0-905788-37-1.

- Toyin Falola; Matt D. Childs (2 May 2005). The Yoruba Diaspora in the Atlantic World (Blacks in the Diaspora). Indiana University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0-253-00301-0.

- "Shotgun Houses". National Park Service: African American Heritage & Ethnography. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- Prof Nnamdi Elleh (2014). Reading the Architecture of the Underprivileged Classes. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 86–88. ISBN 978-1-4094-6786-1.

- Henry John Drewal; Margaret Thompson Drewal (1983). Gẹlẹdẹ: Art and Female Power Among the Yoruba. Indiana University Turkish Studies, Midland books (Traditional arts of Africa). 565. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-32569-3.

- Simon Ottenberg; David Aaron Binkley. Playful Performers: African Children's Masquerades. Transaction Publishers. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-4128-3092-8.

- Nike Lawal; Matthew N. O. Sadiku; Ade Dopamu (22 July 2009). Understanding Yoruba life and culture. Africa World Press (the University of California). ISBN 978-1-59221-025-1.

- "Yoruba Culture". Tribes. 18 September 2007. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- Kamari Maxine Clarke (12 July 2004). Mapping Yorùbá Networks: Power and Agency in the Making of Transnational Communities. Duke University Press. pp. 59, 60. ISBN 978-0-8223-3342-5.

- Traditional Festivals, Vol. 2 [M – Z]. ABC-CLIO. 2005. p. 346. ISBN 978-1-57607-089-5.

- "Behold, new Arugba Osun, who wants to be doctor". Newswatch Times. 31 August 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- Gregory Austin Nwakunor (22 August 2014). "Nigeria: Osun Osogbo 2014 – Arugba's Berth Tastes Green With Goldberg Touch". AllAfrica. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- Alusine Jalloh; Toyin Falola (2008). The United States and West Africa: Interactions and Relations Volume 34 of Rochester studies in African history and the diaspora. University Rochester Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-58046-308-9. ISSN 1092-5228.

- Paul DiMaggio; Patricia Fernandez-Kelly; Gilberto Cârdenas; Yen Espiritu; Amaney Jamal; Sunaina Maira; Douglas Massey; Cecilia Menjivar; Clifford Murphy; Terry Rey; Susan Seifert; Alex Stepick; Mark Stern; Domenic Vitiello; Deborah Wong (13 October 2010). Art in the Lives of Immigrant Communities in the United States Rutgers Series: The Public Life of the Arts. Rutgers University Press, 2010. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-8135-5041-1.

- "Celebrating Eyo the Modern Way". SpyGhana.

- "Royalty in the news: Lagos agog for Eyo Festival today". Kingdoms of Nigeria. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- "Eyo Festival". About Lagos. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- Traditional Festivals, Vol. 2 [M – Z]. ABC-CLIO. 2005. p. 346. ISBN 978-1-57607-089-5. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- Bode Omojola (4 December 2012). Yorùbá Music in the Twentieth Century Identity, Agency, and Performance Practice. University of Rochester Press. ISBN 978-1-58046-409-3. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- Turino, pgs. 181–182; Bensignor, François with Eric Audra, and Ronnie Graham, "Afro-Funksters" and "From Hausa Music to Highlife" in the Rough Guide to World Music, pgs. 432–436 and pgs. 588–600; Karolyi, pg. 43