Alexander Archipenko

Alexander Porfyrovych Archipenko (also referred to as Olexandr, Oleksandr, or Aleksandr; Ukrainian: Олександр Порфирович Архипенко, Romanized: Olexandr Porfyrovych Arkhypenko; May 30, 1887 – February 25, 1964) was a Ukrainian and American avant-garde artist, sculptor, and graphic artist. He was one of the first to apply the principles of Cubism to architecture, analyzing human figure into geometrical forms.[1]

Alexander Archipenko | |

|---|---|

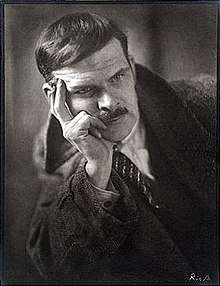

Archipenko around 1920 (photograph by Atelier Riess) | |

| Born | Olexandr Porfyrovych Arkhypenko May 30, 1887 |

| Died | February 25, 1964 (aged 76) New York City, New York U.S. |

| Education | Kiev Art School |

| Known for | Sculpture |

Notable work | The Boxers, 1914 |

| Movement | Cubism |

| Elected | American Academy of Arts and Letters (1962) |

Biography

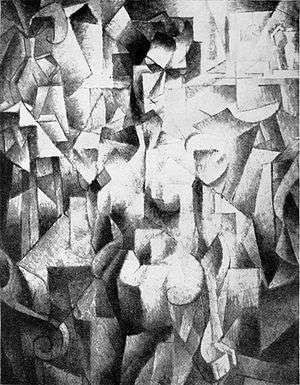

%2C_Salon_d'Automne%2C_1912.jpg)

Alexander Archipenko was born in Kiev (Russian Empire, now Ukraine) in 1887, to Porfiry Antonowych Archipenko and Poroskowia Vassylivna Machowa Archipenko; he was the younger brother of Eugene Archipenko.

From 1902 to 1905 he attended the Kiev Art School (KKHU). In 1906 he continued his education in the arts at Serhiy Svetoslavsky (Kiev), and later that year had an exhibition there with Alexander Bogomazov. He then moved to Moscow where he had a chance to exhibit his work in some group shows.

Archipenko moved to Paris in 1908[2] and was a resident in the artist's colony La Ruche, among émigré Ukrainian artists: Wladimir Baranoff-Rossine, Sonia Delaunay-Terk and Nathan Altman. After 1910 he had exhibitions at Salon des Indépendants, Salon d'Automne together with Aleksandra Ekster, Kazimir Malevich, Vadym Meller, Sonia Delaunay-Terk, Georges Braque, André Derain and others.

In 1912 Archipenko had his first personal exhibition at the Museum Folkwang at Hagen in Germany, and from 1912 to 1914 he was teaching at his own Art School in Paris.

Four of Archipenko's Cubist sculptures, including Family Life and five of his drawings, appeared in the controversial Armory Show in 1913 in New York City. These works were caricatured in the New York World.[3]

Archipenko moved to Nice in 1914. In 1920 he participated in Twelfth Biennale Internazionale dell'Arte di Venezia in Italy and started his own Art school in Berlin the following year. In 1922 Archipenko participated in the First Russian Art Exhibition in the Gallery van Diemen in Berlin together with Aleksandra Ekster, Kazimir Malevich, Solomon Nikritin, El Lissitzky and others.

In 1923 he emigrated to the United States,[2] and participated in an exhibition of Russian Paintings and Sculpture. He became a US citizen in 1929. In 1933 he exhibited at the Ukrainian pavilion in Chicago as part of the Century of Progress World's Fair. Alexander Archipenko contributed the most to the success of the Ukrainian pavilion. His works occupied one room and were valued at $25,000 dollars.[4]

In 1936 Archipenko participated in an exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art in New York as well as numerous exhibitions in Europe and other places in the U.S. He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1962.[5]

Alexander Archipenko died on February 25, 1964, in New York City.[2] He is interred at Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York City.

Contribution to art

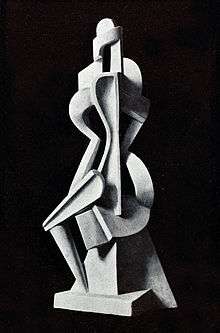

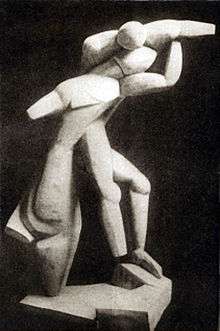

Archipenko, along with the French-Hungarian sculptor Joseph Csaky, exhibited at the first public manifestations of Cubism in Paris; the Salon des Indépendants and Salon d'Automne, 1910 and 1911, being the first, after Picasso,[6] to employ the Cubist style in three dimensions.[2][7] Archipenko departed from the neo-classical sculpture of his time, using faceted planes and negative space to create a new way of looking at the human figure, showing a number of views of the subject simultaneously. He is known for introducing sculptural voids, and for his inventive mixing of genres throughout his career: devising 'sculpto-paintings', and later experimenting with materials such as clear acrylic and terra cotta. Inspired by the works of Picasso and Braque, he is also credited for introducing the collage to wider audiences with his Medrano series.[8][9]

The sculptor Ann Weaver Norton apprenticed with Archipenko for a number of years.[10]

Public collections

Among the public collections holding works by Alexander Archipenko are:

- The Addison Gallery of American Art (Andover, Massachusetts)

- The Art Institute of Chicago

- The Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art (Northwestern University, Illinois)

- Brigham Young University Museum of Art (Utah)

- Chi-Mei Museum (Taiwan)

- The Delaware Art Museum (Wilmington, Delaware)

- The Denver Art Museum (Colorado)

- The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

- The Guggenheim Museum (New York City)

- The Hermitage Museum (Saint Petersburg)

- The Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden (Washington D.C.)

- The Honolulu Museum of Art

- Indiana University Art Museum (Bloomington)

- The Los Angeles County Museum of Art

- The Maier Museum of Art (Randolph-Macon Woman's College, Virginia)

- The Milwaukee Art Museum

- The Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts (Alabama)

- The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

- The Museum of Modern Art (New York City)

- The National Museum of Serbia (Belgrade, Serbia)

- The Nasher Sculpture Center (Dallas, Texas)

- The National Gallery of Art (Washington D.C.)

- National Museum Cardiff

- The North Carolina Museum of Art

- The Norton Simon Museum (Pasadena, California)

- The Peggy Guggenheim Collection (Venice)

- The Philadelphia Museum of Art (Pennsylvania)

- The Phillips Collection (Washington D.C.)

- The Portland Art Museum (Portland, Oregon)

- The Portland Museum of Art (Maine)

- Salisbury House (Des Moines, Iowa)

- The San Antonio Art League Museum (Texas)

- The San Diego Museum of Art (California)

- The Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery (Lincoln, Nebraska)

- The Smithsonian American Art Museum (Washington D.C.)

- Städel Museum (Frankfurt)

- Tate Modern (London)

- The Tel Aviv Museum of Art (Israel)

- The Ukrainian Museum (New York City)

- Von der Heydt-Museum (Wuppertal, Germany)

- Walker Art Center (Minnesota)

- The Cleveland Cultural Gardens (Ukrainian Garden) in Rockefeller Park (Ohio)

- Fundación D.O.P. (Caracas)

- Museum de Fundatie (Zwolle, Netherlands)

Archipenko's statue of King Solomon, at the University of Pennsylvania campus, dominates the walk from 36th and Locust to Walnut. Its creation began in 1964 when, shortly before he died, the artist completed a four–foot sculpture designed for enlargement. His wife oversaw its first casting. In 1968, the 14.5-foot (4.4 m) 1.5-ton statue was produced. In 1985, it was given to the University by Mr and Mrs Jeffrey H. Loria and was installed at its present location. Cubist in form, it has been described as evoking "the feeling of smallness in the face of power that one must have felt standing before King Solomon himself."[11]

Gallery

._Reproduced_in_Archipenko-Album%2C_1921..jpg) Le baiser (The Kiss), 1910

Le baiser (The Kiss), 1910 Portrait de Mme Kameneff

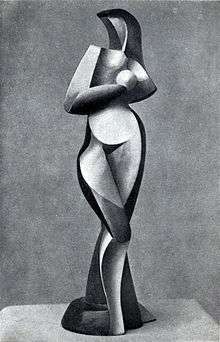

Portrait de Mme Kameneff Venus, 1910–11

Venus, 1910–11._Reproduced_in_Archipenko-Album%2C_1921.jpg) L'Héros (The Hero), ca.1912

L'Héros (The Hero), ca.1912._Reproduced_in_Archipenko-Album%2C_1921.jpg) Femme Marchant (Woman Walking), 1912

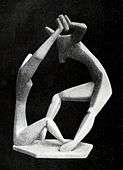

Femme Marchant (Woman Walking), 1912 Dancers (Der Tanz), 1912, original plaster, 24 in. This first version of Dancers was illustrated on the front cover of The Sketch, 29 October 1913, London

Dancers (Der Tanz), 1912, original plaster, 24 in. This first version of Dancers was illustrated on the front cover of The Sketch, 29 October 1913, London.jpg) Zwei Körper (Two Bodies), 1912–13

Zwei Körper (Two Bodies), 1912–13.jpg) Roter Tanz (Danse rouge, Blue Dancer), 1912–13

Roter Tanz (Danse rouge, Blue Dancer), 1912–13%2C_108_x_61.5_x_13.5_cm%2C_Tel_Aviv_Museum_of_Art._Reproduced_in_Archipenko-Album%2C_1921.jpg) Femme à l'Éventail (Woman with a Fan), 1913, Tel Aviv Museum of Art

Femme à l'Éventail (Woman with a Fan), 1913, Tel Aviv Museum of Art Pierrot-carrousel, 1913, painted plaster, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Pierrot-carrousel, 1913, painted plaster, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York%2C_Solomon_R._Guggenheim_Museum%2C_New_York._Reproduced_in_Archipenko-Album%2C_1921.jpg) Danseuse du Médrano (Médrano II), 1914, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

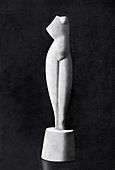

Danseuse du Médrano (Médrano II), 1914, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Flat Torso, 1914

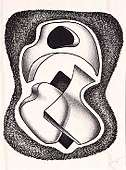

Flat Torso, 1914 Sculpto-peinture

Sculpto-peinture%2C_31.1_x_23.2_cm%2C_gouache_on_paper.jpg) Alexander Archipenko, c.1920, Femme assise (Composition), 31.1 x 23.2 cm, gouache on paper

Alexander Archipenko, c.1920, Femme assise (Composition), 31.1 x 23.2 cm, gouache on paper._Reproduced_in_Archipenko-Album%2C_1921.jpg) Femmes - Vases (Women - Vases), 1919

Femmes - Vases (Women - Vases), 1919 The Gondolier, 1914 (cast 1966), bronze, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Gondolier, 1914 (cast 1966), bronze, Metropolitan Museum of Art.- Woman combing her hair, 1914, bronze, Israel Museum, Jerusalem

Gateway Sculptures, 1950, painted steel, University of Missouri–Kansas City.

Gateway Sculptures, 1950, painted steel, University of Missouri–Kansas City. Le Rendez-Vous des Quatre Formes, from the portfolio Les Formes Vivantes, 1963, lithograph on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Le Rendez-Vous des Quatre Formes, from the portfolio Les Formes Vivantes, 1963, lithograph on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum.- King Solomon on the University of Pennsylvania campus

- The gravesite of Alexander Archipenko in Woodlawn Cemetery, Bronx, NY

Further reading

- Michaelsen, Katherine J.; Nehama Guralnik (1986). Alexander Archipenko A Centennial Tribute. National Gallery of Art, The Tel Aviv Museum.

- Karshan, Donald H. (editor) (1969). Archipenko, International Visionary. Smithsonian Institution Press.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

Notes

- Oxford illustrated encyclopedia. Judge, Harry George., Toyne, Anthony. Oxford [England]: Oxford University Press. 1985–1993. p. 21. ISBN 0-19-869129-7. OCLC 11814265.CS1 maint: others (link) CS1 maint: date format (link)

- "Finding Aid". Alexander Archipenko papers, 1904–1986, (bulk 1930–1964). Archives of American Art. 2011. Retrieved 17 Jun 2011.

- Donald H. Karshan, Archipenko, Content and Continuity 1908–1963, Kovlan Gallery, Chicago, 1968. p. 40.

- Halich, W. (1937) Ukrainians in the United States, Chicago ISBN 0-405-00552-0

- "Deceased Members". American Academy of Arts and Letters. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- File:Womans Head Picasso.jpg Picasso, Woman's Head, modeled on Fernande Olivier

- The Archipenko Foundation, Chronology, 1910–1914 Archived 2013-05-31 at the Wayback Machine

- "Alexander Archipenko | Ukrainian-American artist". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-12-13.

- "Médrano II". Guggenheim. 1913-01-01. Retrieved 2019-12-13.

- Jules Heller; Nancy G. Heller (19 December 2013). North American Women Artists of the Twentieth Century: A Biographical Dictionary. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-63882-5.

- "Campust Gems: King Solomon Statue" by Isaac Kaplan, at 34st.com

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alexander Archipenko. |

- The Archipenko Foundation

- Alexander Archipenko at the Museum of Modern Art

- Alexander Archipenko collection at the Israel Museum. Retrieved September 2016.

- Artcyclopedia page with links to images

- "Refashioning the Figure – The Sketchbooks of Archipenko c.1920", by Marek Bartelik (Henry Moore Institute Essays on Sculpture No. 41) at archipenko.org. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- Archipenko. Catalogue of Exhibition and Description of Archipentura. New York, The Anderson Galleries, 1928.

- Katharine Kuh. Alexander Archipenko. A Memorial Exhibition 1967-1969. The UCLA Art Galleries, 1969.

- Nagy Ildiko, Archipenko Album, 1980

- Alexander Archipenko in American public collections, on the French Sculpture Census website