Acheulean

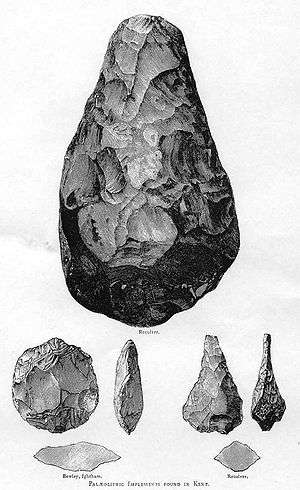

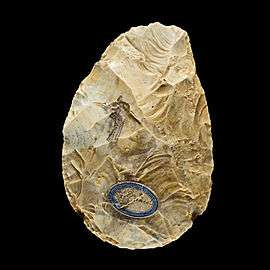

Acheulean (/əˈʃuːliən/; also Acheulian and Mode II), from the French acheuléen after the type site of Saint-Acheul, is an archaeological industry of stone tool manufacture characterized by distinctive oval and pear-shaped "hand-axes" associated with Homo erectus and derived species such as Homo heidelbergensis.

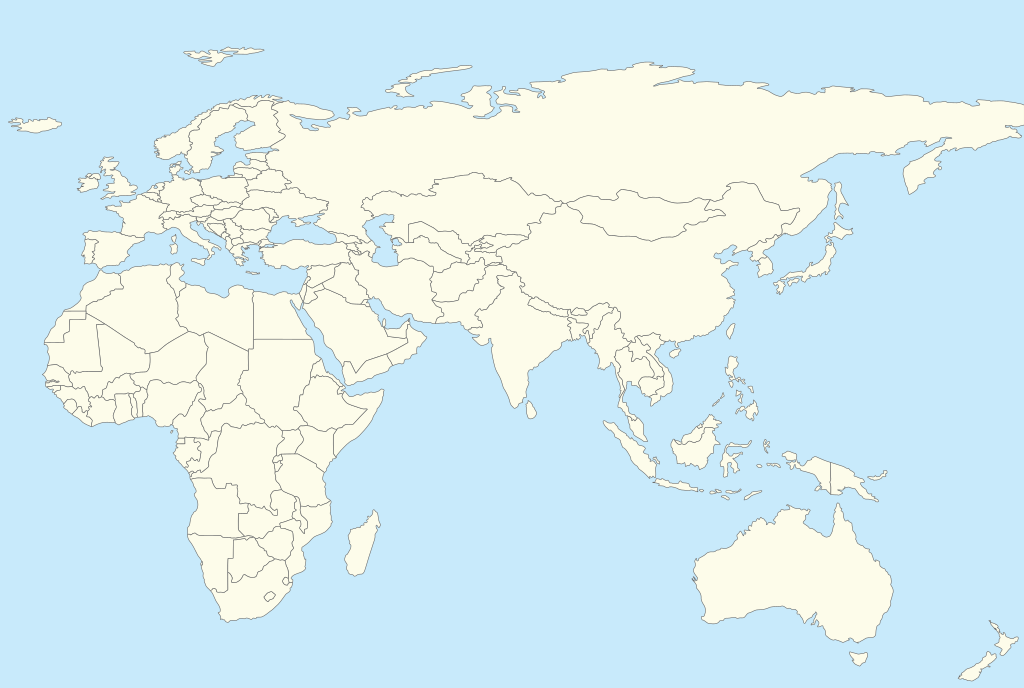

Map of the distribution of Middle Pleistocene (Acheulean) cleaver finds | |

| Geographical range | Africa, Europe, and Asia |

|---|---|

| Period | Lower Paleolithic |

| Dates | 1.76–0.13 Mya |

| Type site | Saint-Acheul (Amiens) |

| Preceded by | Oldowan |

| Followed by | Mousterian, Clactonian, Micoquien |

Acheulean tools were produced during the Lower Palaeolithic era across Africa and much of West Asia, South Asia, East Asia and Europe, and are typically found with Homo erectus remains. It is thought that Acheulean technologies first developed about 1.76 million years ago, derived from the more primitive Oldowan technology associated with Homo habilis.[3] The Acheulean includes at least the early part of the Middle Paleolithic. Its end is not well defined, depending on whether Sangoan (also known as "Epi-Acheulean") is included, it may be taken to last until as late as 130,000 years ago. In Europe and Western Asia, early Neanderthals adopted Acheulean technology, transitioning to Mousterian by about 160,000 years ago.

History of research

The type site for the Acheulean is Saint-Acheul, a suburb of Amiens, the capital of the Somme department in Picardy, where artifacts were found in 1859.[4]

John Frere is generally credited as being the first to suggest a very ancient date for Acheulean hand-axes. In 1797, he sent two examples to the Royal Academy in London from Hoxne in Suffolk. He had found them in prehistoric lake deposits along with the bones of extinct animals and concluded that they were made by people "who had not the use of metals" and that they belonged to a "very ancient period indeed, even beyond the present world".[5] His ideas were, however, ignored by his contemporaries, who subscribed to a pre-Darwinian view of human evolution.

Later, Jacques Boucher de Crèvecœur de Perthes, working between 1836 and 1846, collected further examples of hand-axes and fossilised animal bone from the gravel river terraces of the Somme near Abbeville in northern France. Again, his theories attributing great antiquity to the finds were spurned by his colleagues, until one of de Perthe's main opponents, Dr Marcel Jérôme Rigollot, began finding more tools near Saint Acheul. Following visits to both Abbeville and Saint Acheul by the geologist Joseph Prestwich, the age of the tools was finally accepted.

In 1872, Louis Laurent Gabriel de Mortillet described the characteristic hand-axe tools as belonging to L'Epoque de St Acheul. The industry was renamed as the Acheulean in 1925.

Dating the Acheulean

Providing calendrical dates and ordered chronological sequences in the study of early stone tool manufacture is often accomplished through one or more geological techniques, such as radiometric dating, often potassium-argon dating, and magnetostratigraphy. From the Konso Formation of Ethiopia, Acheulean hand-axes are dated to about 1.5 million years ago using radiometric dating of deposits containing volcanic ashes.[6] Acheulean tools in South Asia have also been found to be dated as far as 1.5 million years ago.[7] However, the earliest accepted examples of the Acheulean currently known come from the West Turkana region of Kenya and were first described by a French-led archaeology team.[8] These particular Acheulean tools were recently dated through the method of magnetostratigraphy to about 1.76 million years ago, making them the oldest not only in Africa but the world.[9] The earliest user of Acheulean tools was Homo ergaster, who first appeared about 1.8 million years ago. Not all researchers use this formal name, and instead prefer to call these users early Homo erectus.[3]

From geological dating of sedimentary deposits, it appears that the Acheulean originated in Africa and spread to Asian, Middle Eastern, and European areas sometime between 1.5 million years ago and about 800 thousand years ago.[10][11] In individual regions, this dating can be considerably refined; in Europe for example, it was thought that Acheulean methods did not reach the continent until around 500,000 years ago. However more recent research demonstrated that hand-axes from Spain were made more than 900,000 years ago.[11]

Relative dating techniques (based on a presumption that technology progresses over time) suggest that Acheulean tools followed on from earlier, cruder tool-making methods, but there is considerable chronological overlap in early prehistoric stone-working industries, with evidence in some regions that Acheulean tool-using groups were contemporary with other, less sophisticated industries such as the Clactonian[12] and then later with the more sophisticated Mousterian, as well. It is therefore important not to see the Acheulean as a neatly defined period or one that happened as part of a clear sequence but as one tool-making technique that flourished especially well in early prehistory. The enormous geographic spread of Acheulean techniques also makes the name unwieldy as it represents numerous regional variations on a similar theme. The term Acheulean does not represent a common culture in the modern sense, rather it is a basic method for making stone tools that was shared across much of the Old World.

The very earliest Acheulean assemblages often contain numerous Oldowan-style flakes and core forms and it is almost certain that the Acheulean developed from this older industry. These industries are known as the Developed Oldowan and are almost certainly transitional between the Oldowan and Acheulean.

Acheulean stone tools

Stages

In the four divisions of prehistoric stone-working,[13] Acheulean artefacts are classified as Mode 2, meaning they are more advanced than the (usually earlier) Mode 1 tools of the Clactonian or Oldowan/Abbevillian industries but lacking the sophistication of the (usually later) Mode 3 Middle Palaeolithic technology, exemplified by the Mousterian industry.

The Mode 1 industries created rough flake tools by hitting a suitable stone with a hammerstone. The resulting flake that broke off would have a natural sharp edge for cutting and could afterwards be sharpened further by striking another smaller flake from the edge if necessary (known as "retouch"). These early toolmakers may also have worked the stone they took the flake from (known as a core) to create chopper cores although there is some debate over whether these items were tools or just discarded cores.[14]

The Mode 2 Acheulean toolmakers also used the Mode 1 flake tool method but supplemented it by using bone, antler, or wood to shape stone tools. This type of hammer, compared to stone, yields more control over the shape of the finished tool. Unlike the earlier Mode 1 industries, it was the core that was prized over the flakes that came from it. Another advance was that the Mode 2 tools were worked symmetrically and on both sides indicating greater care in the production of the final tool.

Mode 3 technology emerged towards the end of Acheulean dominance and involved the Levallois technique, most famously exploited by the Mousterian industry. Transitional tool forms between the two are called Mousterian of Acheulean Tradition, or MTA types. The long blades of the Upper Palaeolithic Mode 4 industries appeared long after the Acheulean was abandoned.

As the period of Acheulean tool use is so vast, efforts have been made to classify various stages of it such as John Wymer's division into Early Acheulean, Middle Acheulean, Late Middle Acheulean and Late Acheulean[15] for material from Britain. These schemes are normally regional and their dating and interpretations vary.[16]

In Africa, there is a distinct difference in the tools made before and after 600,000 years ago with the older group being thicker and less symmetric and the younger being more extensively trimmed.[17]

Manufacture

The primary innovation associated with Acheulean hand-axes is that the stone was worked symmetrically and on both sides. For the latter reason, handaxes are, along with cleavers, bifacially worked tools that could be manufactured from the large flakes themselves or from prepared cores.[18]

Tool types found in Acheulean assemblages include pointed, cordate, ovate, ficron, and bout-coupé hand-axes (referring to the shapes of the final tool), cleavers, retouched flakes, scrapers, and segmental chopping tools. Materials used were determined by available local stone types; flint is most often associated with the tools but its use is concentrated in Western Europe; in Africa sedimentary and igneous rock such as mudstone and basalt were most widely used, for example. Other source materials include chalcedony, quartzite, andesite, sandstone, chert, and shale. Even relatively soft rock such as limestone could be exploited.[19] In all cases the toolmakers worked their handaxes close to the source of their raw materials, suggesting that the Acheulean was a set of skills passed between individual groups.[20]

Some smaller tools were made from large flakes that had been struck from stone cores. These flake tools and the distinctive waste flakes produced in Acheulean tool manufacture suggest a more considered technique, one that required the toolmaker to think one or two steps ahead during work that necessitated a clear sequence of steps to create perhaps several tools in one sitting.

A hard hammerstone would first be used to rough out the shape of the tool from the stone by removing large flakes. These large flakes might be re-used to create tools. The tool maker would work around the circumference of the remaining stone core, removing smaller flakes alternately from each face. The scar created by the removal of the preceding flake would provide a striking platform for the removal of the next. Misjudged blows or flaws in the material used could cause problems, but a skilled toolmaker could overcome them.

Once the roughout shape was created, a further phase of flaking was undertaken to make the tool thinner. The thinning flakes were removed using a softer hammer, such as bone or antler. The softer hammer required more careful preparation of the striking platform and this would be abraded using a coarse stone to ensure the hammer did not slide off when struck.

Final shaping was then applied to the usable cutting edge of the tool, again using fine removal of flakes. Some Acheulean tools were sharpened instead by the removal of a tranchet flake. This was struck from the lateral edge of the hand-axe close to the intended cutting area, resulting in the removal of a flake running along (parallel to) the blade of the axe to create a neat and very sharp working edge. This distinctive tranchet flake can be identified amongst flint-knapping debris at Acheulean sites.

Use

Loren Eiseley calculated[21] that Acheulean tools have an average useful cutting edge of 20 centimetres (8 inches), making them much more efficient than the 5-centimetre (2 in) average of Oldowan tools.

Use-wear analysis on Acheulean tools suggests there was generally no specialization in the different types created and that they were multi-use implements. Functions included hacking wood from a tree, cutting animal carcasses as well as scraping and cutting hides when necessary. Some tools, however, could have been better suited to digging roots or butchering animals than others.

Alternative theories include a use for ovate hand-axes as a kind of hunting discus to be hurled at prey.[22] Puzzlingly, there are also examples of sites where hundreds of hand-axes, many impractically large and also apparently unused, have been found in close association together. Sites such as Melka Kunturé in Ethiopia, Olorgesailie in Kenya, Isimila in Tanzania, and Kalambo Falls in Zambia have produced evidence that suggests Acheulean hand-axes might not always have had a functional purpose.

Recently, it has been suggested that the Acheulean tool users adopted the handaxe as a social artifact, meaning that it embodied something beyond its function of a butchery or wood cutting tool. Knowing how to create and use these tools would have been a valuable skill and the more elaborate ones suggest that they played a role in their owners' identity and their interactions with others. This would help explain the apparent over-sophistication of some examples which may represent a "historically accrued social significance".[24]

One theory goes further and suggests that some special hand-axes were made and displayed by males in search of a mate, using a large, well-made hand-axe to demonstrate that they possessed sufficient strength and skill to pass on to their offspring. Once they had attracted a female at a group gathering, it is suggested that they would discard their axes, perhaps explaining why so many are found together.[25]

Hand-axe as a left over core

Stone knapping with limited digital dexterity makes the center of mass the required direction of flake removal. Physics then dictates a circular or oval end pattern, similar to the handaxe, for a leftover core after flake production. This would explain the abundance, wide distribution, proximity to source, consistent shape, and lack of actual use, of these artifacts.[26]

Money

Mimi Lam, a researcher from the University of British Columbia, has suggested that Acheulean hand-axes became "the first commodity: A marketable good or service that has value and is used as an item for exchange."[27]

Distribution

| The Paleolithic |

|---|

| ↑ Pliocene (before Homo) |

|

|

|

|

Fertile Crescent:

|

| ↓ Mesolithic |

The geographic distribution of Acheulean tools – and thus the peoples who made them – is often interpreted as being the result of palaeo-climatic and ecological factors, such as glaciation and the desertification of the Sahara Desert.[28]

Acheulean stone tools have been found across the continent of Africa, save for the dense rainforest around the River Congo which is not thought to have been colonized by hominids until later. It is thought that from Africa their use spread north and east to Asia: from Anatolia, through the Arabian Peninsula, across modern day Iran[29] and Pakistan, and into India, and beyond. In Europe their users reached the Pannonian Basin and the western Mediterranean regions, modern day France, the Low Countries, western Germany, and southern and central Britain. Areas further north did not see human occupation until much later, due to glaciation. In Athirampakkam at Chennai in Tamil Nadu the Acheulean age started at 1.51 mya and it is also prior than North India and Europe.[30]

Until the 1980s, it was thought that the humans who arrived in East Asia abandoned the hand-axe technology of their ancestors and adopted chopper tools instead. An apparent division between Acheulean and non-Acheulean tool industries was identified by Hallam L. Movius, who drew the Movius Line across northern India to show where the traditions seemed to diverge. Later finds of Acheulean tools at Chongokni in South Korea and also in Mongolia and China, however, cast doubt on the reliability of Movius's distinction.[31] Since then, a different division known as the Roe Line has been suggested. This runs across North Africa to Israel and thence to India, separating two different techniques used by Acheulean toolmakers. North and east of the Roe Line, Acheulean hand-axes were made directly from large stone nodules and cores; while, to the south and west, they were made from flakes struck from these nodules.[32]

_Amar_Merdeg%2C_Mehran%2C_Ilam%2C_Lower_Paleolithic%2C_National_Museum_of_Iran.jpg)

Acheulean tool users

Most notably, however, it is Homo ergaster (sometimes called early Homo erectus), whose assemblages are almost exclusively Acheulean, who used the technique. Later, the related species Homo heidelbergensis (the common ancestor of both Neanderthals and Homo sapiens) used it extensively. Late Acheulean tools were still used by species derived from H. erectus, including Homo sapiens idaltu and early Neanderthals.[33]

The symmetry of the hand-axes has been used to suggest that Acheulean tool users possessed the ability to use language;[34] the parts of the brain connected with fine control and movement are located in the same region that controls speech. The wider variety of tool types compared to earlier industries and their aesthetically as well as functionally pleasing form could indicate a higher intellectual level in Acheulean tool users than in earlier hominines.[35] Others argue that there is no correlation between spatial abilities in tool making and linguistic behaviour, and that language is not learned or conceived in the same manner as artefact manufacture.[36]

Lower Palaeolithic finds made in association with Acheulean hand-axes, such as the Venus of Berekhat Ram,[37] have been used to argue for artistic expression amongst the tool users. The incised elephant tibia from Bilzingsleben[38] in Germany, and ochre finds from Kapthurin in Kenya[39] and Duinefontein in South Africa,[40] are sometimes cited as being some of the earliest examples of an aesthetic sensibility in human history. There are numerous other explanations put forward for the creation of these artefacts; however, evidence of human art did not become commonplace until around 50,000 years ago, after the emergence of modern Homo sapiens.[41]

The kill site at Boxgrove in England is another famous Acheulean site. Up until the 1970s these kill sites, often at waterholes where animals would gather to drink, were interpreted as being where Acheulean tool users killed game, butchered their carcasses, and then discarded the tools they had used. Since the advent of zooarchaeology, which has placed greater emphasis on studying animal bones from archaeological sites, this view has changed. Many of the animals at these kill sites have been found to have been killed by other predator animals, so it is likely that humans of the period supplemented hunting with scavenging from already dead animals.[42]

Excavations at the Bnot Ya'akov Bridge site, located along the Dead Sea rift in the southern Hula Valley of northern Israel, have revealed evidence of human habitation in the area from as early as 750,000 years ago.[43] Archaeologists from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem claim that the site provides evidence of "advanced human behavior" half a million years earlier than has previously been estimated. Their report describes an Acheulean layer at the site in which numerous stone tools, animal bones, and plant remains have been found.[44]

Azykh cave located in Azerbaijan is another site where Acheulean tools were found. In 1968, a lower jaw of a new type of hominid was discovered in the 5th layer (so-called Acheulean layer) of the cave. Specialists named this type “Azykhantropus”.[45][46][47]

Only limited artefactual evidence survives of the users of Acheulean tools other than the stone tools themselves. Cave sites were exploited for habitation, but the hunter-gatherers of the Palaeolithic also possibly built shelters such as those identified in connection with Acheulean tools at Grotte du Lazaret[48] and Terra Amata near Nice in France. The presence of the shelters is inferred from large rocks at the sites, which may have been used to weigh down the bottoms of tent-like structures or serve as foundations for huts or windbreaks. These stones may have been naturally deposited. In any case, a flimsy wood or animal skin structure would leave few archaeological traces after so much time. Fire was seemingly being exploited by Homo ergaster, and would have been a necessity in colonising colder Eurasia from Africa. Conclusive evidence of mastery over it this early is, however, difficult to find.

See also

- Oldowan

- Lithic reduction

- Lower Palaeolithic

- Palaeolithic

- Stone Age

- Stone tools

- Ndutu cranium

References

- Hadfield, Peter (4 March 2000). "Gimme shelter". New Scientist.

- "Earliest evidence of art found". BBC News. 2 May 2000.

- Wood, B, 2005, p87.

- Oxford English Dictionary 2nd Ed. (1989)

- Frere, John.

- Asfaw, Berhane; Beyene, Yonas; Suwa, Gen; Walter, Robert C.; White, Tim D.; WoldeGabriel, Giday; Yemane, Tesfaye (December 1992). "The earliest Acheulean from Konso-Gardula". Nature. 360 (6406): 732–735. Bibcode:1992Natur.360..732A. doi:10.1038/360732a0. PMID 1465142.

- Pappu, Shanti; Gunnell, Yanni; Akhilesh, Kumar; Braucher, Régis; Taieb, Maurice; Demory, François; Thouveny, Nicolas (25 March 2011). "Early Pleistocene Presence of Acheulian Hominins in South India". Science. 331 (6024): 1596–1599. Bibcode:2011Sci...331.1596P. doi:10.1126/science.1200183. PMID 21436450.

- Roche, Hélène; Brugal, Jean-Philip; Delagnes, Anne; Feibel, Craig; Harmand, Sonia; Kibunjia, Mzalendo; Prat, Sandrine; Texier, Pierre-Jean (December 2003). "Les sites archéologiques plio-pléistocènes de la formation de Nachukui, Ouest-Turkana, Kenya : bilan synthétique 1997–2001". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 2 (8): 663–673. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2003.06.001.

- Lepre, Christopher J.; Roche, Hélène; Kent, Dennis V.; Harmand, Sonia; Quinn, Rhonda L.; Brugal, Jean-Philippe; Texier, Pierre-Jean; Lenoble, Arnaud; Feibel, Craig S. (September 2011). "An earlier origin for the Acheulian". Nature. 477 (7362): 82–85. Bibcode:2011Natur.477...82L. doi:10.1038/nature10372. PMID 21886161.

- Goren-Inbar, N.; Feibel, C. S.; Verosub, K. L.; Melamed, Y.; Kislev, M. E.; Tchernov, E.; Saragusti, I. (2000). "Pleistocene Milestones on the Out-of-Africa Corridor at Gesher Benot Ya'aqov, Israel". Science. 289 (5481): 944–947. Bibcode:2000Sci...289..944G. doi:10.1126/science.289.5481.944. PMID 10937996.

- Scott, Gary R.; Gibert, Luis (September 2009). "The oldest hand-axes in Europe". Nature. 461 (7260): 82–85. Bibcode:2009Natur.461...82S. doi:10.1038/nature08214. PMID 19727198.

- Ashton, Nick; McNabb, John; Irving, Brian; Lewis, Simon; Parfitt, Simon (2 January 2015). "Contemporaneity of Clactonian and Acheulian flint industries at Barnham, Suffolk". Antiquity. 68 (260): 585–589. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00047074.

- Barton, RNE, Stone Age Britain English Heritage/BT Batsford:London 1997 qtd in Butler, 2005. See also Wymer, JJ, The Lower Palaeolithic Occupation of Britain, Wessex Archaeology and English Heritage, 1999.

- Ashton, NM, McNabb, J, and Parfitt, S, Choppers and the Clactonian, a reinvestigation, Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 58, pp21–28, qtd in Butler, 2005

- Wymer, JJ, 1968, Lower Palaeolithic Archaeology in Britain: as represented by the Thames Valley, qtd in Adkins, L and R, 1998

- Collins, D, 1978, Early Man in West Middlesex, qtd in Adkins, L and R, 1998

- Stout, Dietrich; Apel, Jan; Commander, Julia; Roberts, Mark (January 2014). "Late Acheulean technology and cognition at Boxgrove, UK". Journal of Archaeological Science. 41: 576–590. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2013.10.001.

- Barham, Lawrence; Mitchell, Peter (2008). The First Africans (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-521-61265-4.

- Paddayya, K.; Jhaldiyal, Richa; Petraglia, M.D. (2 January 2015). "Excavation of an Acheulian workshop at Isampur, Karnataka (India)". Antiquity. 74 (286): 751–752. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00060269.

- Gamble, C and Steele, J, 1999, Hominid ranging patterns and dietary strategies in Ullrich, H (ed.), Hominid evolution: lifestyles and survival strategies, pp 396–409, Gelsenkirchen: Edition Archaea.

- Unattributed citation in Renfrew and Bahn, 1991, p277

- O'Brien, Eileen M. (February 1981). "The Projectile Capabilities of an Acheulian Handaxe From Olorgesailie". Current Anthropology. 22 (1): 76–79. doi:10.1086/202607. See also Calvin, W, 1993, The unitary hypothesis: a common neural circuitry for novel manipulations, language, plan-ahead and throwing, in K.R. Gibson & T. Ingold (ed.), Tools, language and cognition in human evolution: 230–50. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- White, Mark J. (18 February 2014). "On the Significance of Acheulean Biface Variability in Southern Britain". Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. 64: 15–44. doi:10.1017/S0079497X00002164.

- Kohn, Marek; Mithen, Steven (2 January 2015). "Handaxes: products of sexual selection?". Antiquity. 73 (281): 518–526. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00065078.

- "The Acheulean Handaxe".

- Welsh, Jennifer (1 March 2012). "Tools May Have Been First Money". LiveScience.

- Todd, Lawrence; Glantz, Michelle; Kappelman, John (2 January 2015). "Chilga Kernet: an Acheulean landscape on Ethiopia's western plateau". Antiquity. 76 (293): 611–612. doi:10.1017/S0003598X0009089X.

- Biglari, Fereidoun; Shidrang, Sonia (September 2006). "The Lower Paleolithic Occupation of Iran". Near Eastern Archaeology. 69 (3–4): 160–168. doi:10.1086/NEA25067668.

- Prasad, R. (24 March 2011). "Acheulian stone tools discovered near Chennai". The Hindu.

- Hyeong Woo Lee, The Palaeolithic industries of Korea: chronology and related new findspots in Milliken, S and Cook, J (eds), 2001

- Gamble, C and Marshall, G, The shape of handaxes, the structure of the Acheulian world, in Milliken, S and Cook, J (eds), 2001

- Clark, J. Desmond; Beyene, Yonas; WoldeGabriel, Giday; Hart, William K.; Renne, Paul R.; Gilbert, Henry; Defleur, Alban; Suwa, Gen; Katoh, Shigehiro; Ludwig, Kenneth R.; Boisserie, Jean-Renaud; Asfaw, Berhane; White, Tim D. (June 2003). "Stratigraphic, chronological and behavioural contexts of Pleistocene Homo sapiens from Middle Awash, Ethiopia". Nature. 423 (6941): 747–752. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..747C. doi:10.1038/nature01670. PMID 12802333.

- Isaac, Glynn L. (October 1976). "Stages of Cultural Elaboration in the Pleistocene: Possible Archaeological Indicators of the Development of Language Capabilities". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 280 (1 Origins and E): 275–288. Bibcode:1976NYASA.280..275I. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1976.tb25494.x.

- Wynn, Thomas (June 1995). "Handaxe enigmas". World Archaeology. 27 (1): 10–24. doi:10.1080/00438243.1995.9980290.

- Dibble, HL, 1989, The implications of stone tool types for the presenceof language during the Lower and Middle Palaeolithic, in The Human Revolution (P Mellars and C Stringer eds) Edinburgh University Press, qtd in Renfrew and Bahn, 1991.

- Goren-Inbar, N and Peltz, S, 1995, Additional remarks on the Berekhat Ram figure, Rock Art Research 12, 131–132, qtd in Scarre, 2005

- Mania, D and Mania, U, 1988, Deliberate engravings on bone artefacts of Homo Erectus, Rock Art Research 5, 919–7, qtd in Scarre, 2005

- Tryon, Christian A.; McBrearty, Sally (January 2002). "Tephrostratigraphy and the Acheulian to Middle Stone Age transition in the Kapthurin Formation, Kenya". Journal of Human Evolution. 42 (1–2): 211–235. doi:10.1006/jhev.2001.0513. PMID 11795975.

- Cruz-Uribe, Kathryn; Klein, Richard G; Avery, Graham; Avery, Margaret; Halkett, David; Hart, Timothy; Milo, Richard G; Garth Sampson, C; Volman, Thomas P (1 May 2003). "Excavation of buried Late Acheulean (Mid-Quaternary) land surfaces at Duinefontein 2, Western Cape Province, South Africa". Journal of Archaeological Science. 30 (5): 559–575. doi:10.1016/S0305-4403(02)00202-9.

- Scarre, 2005, chapter 3, p118 "However, objects whose artistic meaning is unequivocal become commonplace only after 50,000 years ago, when they are associated with the origins and spread of fully modern humans from Africa.

- ...the most conservative conclusion today is that Acheulean people and their contemporaries definitely hunted big animals, though their success rate is not clear ibid, p 120.

- Gesher Benot Ya'aqov Archived 2009-07-20 at the Wayback Machine, Hebrew University, Retrieved 2010-01-05.

- Siegel-Itzkovich, Judy (December 22, 2009). "HU: Evidence of advanced human life half a million years earlier than previously thought". The Jerusalem Post.

- Pavel Dolukhanov (2014). The Early Slavs: Eastern Europe from the Initial Settlement to the Kievan Rus. Routledge. ISBN 9781317892229.

- V.A. Zubakov, I.I. Borzenkova (1990). Global Palaeoclimate of the Late Cenozoic. Elsevier. ISBN 9780080868530.

- Ian Shaw, Robert Jameson, ed. (2008). A Dictionary of Archaeology. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470751961.

- De Lumley, 1975, Cultural evolution in France in its palaeoecological setting during the middle Pleistocene, in After the Australopithecines, Butzer, KW and Issac, G Ll. (eds) 745–808. The Hague:Mouton, qtd in Scarre, 2005

Bibliography

- Adkins, L; and R (1998). The Handbook of British Archaeology. London: Constable. ISBN 978-0-09-478330-0.

- Butler, C (2005). Prehistoric Flintwork. Tempus, Stroud. ISBN 978-0-7524-3340-0.

- Milliken, S; and J Cook (eds) (2001). A Very Remote Period Indeed. Papers on the Palaeolithic presented to Derek Roe. Oxford: Oxbow. ISBN 978-1-84217-056-4.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Renfrew, C; and P Bahn (1991). Archaeology, Theories Methods and Practice. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-27605-1.

- Scarre, C (ed.) (2005). The Human Past. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28531-2.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Wood, B (2005). Human Evolution A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280360-3.

External links

| Look up Acheulean in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |