Archaic smile

The archaic smile was used by sculptors in Archaic Greece,[1][2] especially in the second quarter of the 6th century BCE, possibly to suggest that their subject was alive and infused with a sense of well-being. One of the most famous examples of the Archaic Smile is the Kroisos Kouros, and the Peplos Kore is another.

.jpg)

The dying warrior from the west pediment of the Temple of Aphaia, Aegina, Greece is an interesting context, as the warrior is near death.

In the Archaic Period of ancient Greece (roughly 600 BCE to 480 BCE), the art that proliferated contained images of people who had the archaic smile.[1][2]

For two centuries before the mid-5th century BCE, the archaic smile was widely sculpted, as evidenced by statues found in excavations all across the Greek mainland, Asia Minor, and on islands in the Aegean Sea.[1] It has been theorized that in thay period, artists felt it either represents that they were blessed by the gods in their actions and so was the smile, or that it is similar to preplanned smiles in modern photos..

The significance of the convention is not known although it is often assumed that for the Greeks, that kind of smile reflected a state of ideal health and well-being. It is best anthropological practice to assume expertise in execution of craft and to look for formal/stylistic reasons for cultural artifacts to appear as they do.[3]

It has also been suggested that it is simply the result of a technical difficulty in fitting the curved shape of the mouth to the somewhat-blocklike head typical of Archaic sculpture. Richard Neer theorizes that the archaic ile may actually be a marker of status since aristocrats of multiple cities throughout Greece were referred to as the Geleontes or "smiling ones".[4]

There are alternative views to the archaic smile being "flat and quite unnatural looking". That is how John Fowles describes the archaic smile in his novel The Magus (Chapter 23): "...full of the purest metaphysical good humour [...] timelessly intelligent and timelessly amused. [...] Because a star explodes and a thousand worlds like ours die, we know this world is. That is the smile: that what might not be, is [...] When I die, I shall have this by my bedside. It is the last human face I want to see." To viewers habituated to realism, it could be seen as a movement towards naturalism.

Kouros of Tenea, 560-550 BCE, Glyptothek Munich

Kouros of Tenea, 560-550 BCE, Glyptothek Munich Head of a kouros in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens

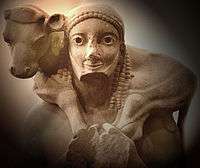

Head of a kouros in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens The Moscophoros of the Acropolis, ca 570 BCE

The Moscophoros of the Acropolis, ca 570 BCE Votive sphinx from the Acropolis

Votive sphinx from the Acropolis Warrior from the west pediment of the Temple of Aphaia, Glyptothek Munich

Warrior from the west pediment of the Temple of Aphaia, Glyptothek Munich

See also

References

- A Brief History of the Smile, Angus Trumble, 2005, ISBN 0-465-08779-5, p.11, Google Books link: books-google-AT11.

- "Archaic smile", Britannica Online Encyclopedia, 2009, webpage: EB-Smile.

- Middle Archaic Phase(Smile) Retrieved 24 September 2010

- Neer, Richard (2012). Greek Art and Archaeology. New York: Thames & Hudson. p. 156. ISBN 9780500288771.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Archaic smile. |