Commodus

Commodus (/ˈkɒmədəs/;[3] 31 August 161 – 31 December 192) was Roman emperor with his father Marcus Aurelius from 177 until his father's death in 180, and solely until 192. His reign is commonly considered to mark the end of the golden period in the history of the Roman Empire known as the Pax Romana.

| Commodus | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

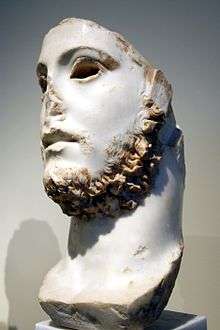

Bust of Commodus at J. Paul Getty Museum | |||||

| Roman emperor | |||||

| Reign | 177 – 31 December 192 | ||||

| Predecessor | Marcus Aurelius (co-emperor until 180) | ||||

| Successor | Pertinax | ||||

| Born | 31 August 161 Lanuvium, near Rome | ||||

| Died | 31 December 192 (aged 31) Rome | ||||

| Burial | Rome | ||||

| Spouse | Bruttia Crispina | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Nerva–Antonine | ||||

| Father | Marcus Aurelius | ||||

| Mother | Faustina | ||||

| Roman imperial dynasties | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nerva–Antonine dynasty (AD 96–192) | ||||||||||||||

| Chronology | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Family | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Succession | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

He accompanied Marcus his father during the Marcomannic Wars in 172 and on a tour of the Eastern provinces in 176. He was made the youngest consul in Roman history in 177 and later that year elevated to co-emperor with his father.

During his solo reign, the Empire enjoyed a period of reduced military conflict compared with the reign of Marcus Aurelius, but intrigues and conspiracies abounded, leading Commodus to an increasingly dictatorial style of leadership that culminated in a god-like personality cult, with him performing as a gladiator in the Colosseum. His assassination in 192 marked the end of the Nerva–Antonine dynasty. He was succeeded by Pertinax, the first emperor in the tumultuous Year of the Five Emperors.

Early life and rise to power (161–180)

Early life

Commodus was born on 31 August AD 161 in Lanuvium, near Rome.[4] He was the son of the reigning emperor, Marcus Aurelius, and Aurelius's first cousin, Faustina the Younger, the youngest daughter of Emperor Antoninus Pius, who had died only a few months before. Commodus had an elder twin brother, Titus Aurelius Fulvus Antoninus, who died in 165. On 12 October 166, Commodus was made Caesar together with his younger brother, Marcus Annius Verus.[5][6] The latter died in 169 having failed to recover from an operation, which left Commodus as Marcus Aurelius's sole surviving son.[6]

He was looked after by his father's physician, Galen,[7][8] who treated many of Commodus' common illnesses. Commodus received extensive tutoring by a multitude of teachers with a focus on intellectual education.[9] Among his teachers, Onesicrates, Antistius Capella, Titus Aius Sanctus, and Pitholaus are mentioned.[9][10]

Commodus is known to have been at Carnuntum, the headquarters of Marcus Aurelius during the Marcomannic Wars, in 172. It was presumably there that, on 15 October 172, he was given the victory title Germanicus, in the presence of the army. The title suggests that Commodus was present at his father's victory over the Marcomanni. On 20 January 175, Commodus entered the College of Pontiffs, the starting point of a career in public life.

In April 175, Avidius Cassius, Governor of Syria, declared himself Emperor following rumours that Marcus Aurelius had died. Having been accepted as Emperor by Syria, Judea and Egypt, Cassius carried on his rebellion even after it had become obvious that Marcus was still alive. During the preparations for the campaign against Cassius, Commodus assumed his toga virilis on the Danubian front on 7 July 175, thus formally entering adulthood. Cassius, however, was killed by one of his centurions before the campaign against him could begin.

Commodus subsequently accompanied his father on a lengthy trip to the Eastern provinces, during which he visited Antioch. The Emperor and his son then traveled to Athens, where they were initiated into the Eleusinian mysteries. They then returned to Rome in the autumn of 176.

Joint rule with father (177)

Marcus Aurelius was the first emperor since Vespasian to have a legitimate biological son and, though he himself was the fifth in the line of the so-called Five Good Emperors, each of whom had adopted his successor, it seems to have been his firm intention that Commodus should be his heir. On 27 November 176, Marcus Aurelius granted Commodus the rank of Imperator and, in the middle of 177, the title Augustus, giving his son the same status as his own and formally sharing power.

Commodus was the first (and until 337, the only) emperor "born in the purple", meaning during his father's reign.

On 23 December 176, the two Augusti celebrated a joint triumph, and Commodus was given tribunician power. On 1 January 177, Commodus became consul for the first time, which made him, aged 15, the youngest consul in Roman history up to that time. He subsequently married Bruttia Crispina before accompanying his father to the Danubian front once more in 178. Marcus Aurelius died there on 17 March 180, leaving the 18-year-old Commodus sole emperor.

Solo reign (180–192)

Upon his ascension, Commodus devalued the Roman currency. He reduced the weight of the denarius from 96 per Roman pound to 105 per Roman pound (3.85 grams to 3.35 grams). He also reduced the silver purity from 79 percent to 76 percent – the silver weight dropping from 2.57 grams to 2.34 grams. In 186 he further reduced the purity and silver weight to 74 percent and 2.22 grams respectively, being 108 to the Roman pound.[11] His reduction of the denarius during his rule was the largest since the empire's first devaluation during Nero's reign.

Whereas the reign of Marcus Aurelius had been marked by almost continuous warfare, Commodus' rule was comparatively peaceful in the military sense, but was also characterised by political strife and the increasingly arbitrary and capricious behaviour of the emperor himself. In the view of Dio Cassius, his accession marked the descent "from a kingdom of gold to one of iron and rust".[12]

Despite his notoriety, and considering the importance of his reign, Commodus' years in power are not well chronicled. The principal surviving literary sources are Herodian, Dio Cassius (a contemporary and sometimes first-hand observer, Senator during Commodus' reign, but his reports for this period survive only as fragments and abbreviations), and the Historia Augusta (untrustworthy for its character as a work of literature rather than history, with elements of fiction embedded within its biographies; in the case of Commodus, it may well be embroidering upon what the author found in reasonably good contemporary sources).

Commodus remained with the Danube armies for only a short time before negotiating a peace treaty with the Danubian tribes. He then returned to Rome and celebrated a triumph for the conclusion of the wars on 22 October 180. Unlike the preceding Emperors Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius, he seems to have had little interest in the business of administration and tended throughout his reign to leave the practical running of the state to a succession of favourites, beginning with Saoterus, a freedman from Nicomedia who had become his chamberlain.

Dissatisfaction with this state of affairs would lead to a series of conspiracies and attempted coups, which in turn eventually provoked Commodus to take charge of affairs, which he did in an increasingly dictatorial manner. Nevertheless, though the senatorial order came to hate and fear him, the evidence suggests that he remained popular with the army and the common people for much of his reign, not least because of his lavish shows of largesse (recorded on his coinage) and because he staged and took part in spectacular gladiatorial combats.

One of the ways he paid for his donatives (imperial handouts) and mass entertainments was to tax the senatorial order, and on many inscriptions, the traditional order of the two nominal powers of the state, the Senate and People (Senatus Populusque Romanus) is provocatively reversed (Populus Senatusque...).

Conspiracies of 182

At the outset of his reign, Commodus, aged 18, inherited many of his father's senior advisers, notably Tiberius Claudius Pompeianus (the second husband of Commodus' eldest sister Lucilla), his father-in-law Gaius Bruttius Praesens, Titus Fundanius Vitrasius Pollio, and Aufidius Victorinus, who was Prefect of the City of Rome. He also had four surviving sisters, all of them with husbands who were potential rivals. Lucilla was over ten years his senior and held the rank of Augusta as the widow of her first husband, Lucius Verus.

The first crisis of the reign came in 182, when Lucilla engineered a conspiracy against her brother. Her motive is alleged to have been envy of the Empress Crispina. Her husband, Pompeianus, was not involved, but two men alleged to have been her lovers, Marcus Ummidius Quadratus Annianus (the consul of 167, who was also her first cousin) and Appius Claudius Quintianus, attempted to murder Commodus as he entered a theater. They bungled the job and were seized by the emperor's bodyguard.

Quadratus and Quintianus were executed. Lucilla was exiled to Capri and later killed. Pompeianus retired from public life. One of the two praetorian prefects, Publius Tarrutenius Paternus, had actually been involved in the conspiracy but his involvement was not discovered until later on, and in the aftermath, he and his colleague, Sextus Tigidius Perennis, were able to arrange for the murder of Saoterus, the hated chamberlain.

Commodus took the loss of Saoterus badly, and Perennis now seized the chance to advance himself by implicating Paternus in a second conspiracy, one apparently led by Publius Salvius Julianus, who was the son of the jurist Salvius Julianus and was betrothed to Paternus' daughter. Salvius and Paternus were executed along with a number of other prominent consulars and senators. Didius Julianus, the future emperor and a relative of Salvius Julianus, was dismissed from the governorship of Germania Inferior.

Cleander

Perennis took over the reins of government and Commodus found a new chamberlain and favourite in Cleander, a Phrygian freedman who had married one of the emperor's mistresses, Demostratia. Cleander was in fact the person who had murdered Saoterus. After those attempts on his life, Commodus spent much of his time outside Rome, mostly on the family estates at Lanuvium. As he was physically strong, his chief interest was in sport: he took part in horse racing, chariot racing, and combats with beasts and men, mostly in private but also on occasion in public.

Dacia and Britain

Commodus was inaugurated in 183 as consul with Aufidius Victorinus for a colleague and assumed the title Pius. War broke out in Dacia: few details are available, but it appears two future contenders for the throne, Clodius Albinus and Pescennius Niger, both distinguished themselves in the campaign. Also, in Britain in 184, the governor Ulpius Marcellus re-advanced the Roman frontier northward to the Antonine Wall, but the legionaries revolted against his harsh discipline and acclaimed another legate, Priscus, as emperor.[15]

Priscus refused to accept their acclamations, and Perennis had all the legionary legates in Britain cashiered. On 15 October 184 at the Capitoline Games, a Cynic philosopher publicly denounced Perennis before Commodus. His tale wasn't believed and he was immediately put to death. According to Dio Cassius, Perennis, though ruthless and ambitious, was not personally corrupt and generally administered the state well.[15]

However, the following year, a detachment of soldiers from Britain (they had been drafted to Italy to suppress brigands) also denounced Perennis to the emperor as plotting to make his own son emperor (they had been enabled to do so by Cleander, who was seeking to dispose of his rival), and Commodus gave them permission to execute him as well as his wife and sons. The fall of Perennis brought a new spate of executions: Aufidius Victorinus committed suicide. Ulpius Marcellus was replaced as governor of Britain by Pertinax; brought to Rome and tried for treason, Marcellus narrowly escaped death.

Cleander's zenith and fall (185–190)

Cleander proceeded to concentrate power in his own hands and to enrich himself by becoming responsible for all public offices: he sold and bestowed entry to the Senate, army commands, governorships and, increasingly, even the suffect consulships to the highest bidder. Unrest around the empire increased, with large numbers of army deserters causing trouble in Gaul and Germany. Pescennius Niger mopped up the deserters in Gaul in a military campaign, and a revolt in Brittany was put down by two legions brought over from Britain.

In 187, one of the leaders of the deserters, Maternus, came from Gaul intending to assassinate Commodus at the Festival of the Great Goddess in March, but he was betrayed and executed. In the same year, Pertinax unmasked a conspiracy by two enemies of Cleander – Antistius Burrus (one of Commodus' brothers-in-law) and Arrius Antoninus. As a result, Commodus appeared even more rarely in public, preferring to live on his estates.

Early in 188, Cleander disposed of the current praetorian prefect, Atilius Aebutianus, and took over supreme command of the Praetorian Guard at the new rank of a pugione ("dagger-bearer"), with two praetorian prefects subordinate to him. Now at the zenith of his power, Cleander continued to sell public offices as his private business. The climax came in the year 190, which had 25 suffect consuls – a record in the 1,000-year history of the Roman consulship—all appointed by Cleander (they included the future Emperor Septimius Severus).

In the spring of 190, Rome was afflicted by a food shortage, for which the praefectus annonae Papirius Dionysius, the official actually in charge of the grain supply, contrived to lay the blame on Cleander. At the end of June, a mob demonstrated against Cleander during a horse race in the Circus Maximus: he sent the Praetorian Guard to put down the disturbances, but Pertinax, who was now City Prefect of Rome, dispatched the Vigiles Urbani to oppose them. Cleander fled to Commodus, who was at Laurentum in the house of the Quinctilii, for protection, but the mob followed him calling for his head.

At the urging of his mistress Marcia, Commodus had Cleander beheaded and his son killed. Other victims at this time were the praetorian prefect Julius Julianus, Commodus' cousin Annia Fundania Faustina, and his brother-in-law Mamertinus. Papirius Dionysius was executed, too.

The emperor now changed his name to Lucius Aelius Aurelius Commodus. At 29, he took over more of the reins of power, though he continued to rule through a cabal consisting of Marcia, his new chamberlain Eclectus, and the new praetorian prefect Quintus Aemilius Laetus.

Megalomania (190–192)

_obverse.jpg)

In opposition to the Senate, in his pronouncements and iconography, Commodus had always stressed his unique status as a source of god-like power, liberality, and physical prowess. Innumerable statues around the empire were set up portraying him in the guise of Hercules, reinforcing the image of him as a demigod, a physical giant, a protector, and a warrior who fought against men and beasts (see "Commodus and Hercules" and "Commodus the Gladiator" below). Moreover, as Hercules, he could claim to be the son of Jupiter, the supreme god of the Roman pantheon. These tendencies now increased to megalomaniacal proportions. Far from celebrating his descent from Marcus Aurelius, the actual source of his power, he stressed his own personal uniqueness as the bringer of a new order, seeking to re-cast the empire in his own image.

During 191, the city of Rome was extensively damaged by a fire that raged for several days, during which many public buildings including the Temple of Pax, the Temple of Vesta, and parts of the imperial palace were destroyed.

Perhaps seeing this as an opportunity, early in 192 Commodus, declaring himself the new Romulus, ritually re-founded Rome, renaming the city Colonia Lucia Annia Commodiana. All the months of the year were renamed to correspond exactly with his (now twelve) names: Lucius, Aelius, Aurelius, Commodus, Augustus, Herculeus, Romanus, Exsuperatorius, Amazonius, Invictus, Felix, and Pius. The legions were renamed Commodianae, the fleet which imported grain from Africa was termed Alexandria Commodiana Togata, the Senate was entitled the Commodian Fortunate Senate, his palace and the Roman people themselves were all given the name Commodianus, and the day on which these reforms were decreed was to be called Dies Commodianus.[16]

Thus, he presented himself as the fountainhead of the Empire, Roman life, and religion. He also had the head of the Colossus of Nero adjacent to the Colosseum replaced with his own portrait, gave it a club, and placed a bronze lion at its feet to make it look like Hercules Romanus, and added an inscription boasting of being "the only left-handed fighter to conquer twelve times one thousand men".[17]

Assassination (192)

_2012-09-30_008.jpg)

In November 192, Commodus held Plebeian Games, in which he shot hundreds of animals with arrows and javelins every morning, and fought as a gladiator every afternoon, winning all the fights. In December, he announced his intention to inaugurate the year 193 as both consul and gladiator on 1 January.

At this point, the prefect Laetus formed a conspiracy with Eclectus to supplant Commodus with Pertinax, taking Marcia into their confidence. On 31 December, Marcia poisoned Commodus' food but he vomited up the poison, so the conspirators sent his wrestling partner Narcissus to strangle him in his bath. Upon his death, the Senate declared him a public enemy (a de facto damnatio memoriae) and restored the original name of the city of Rome and its institutions. Statues of Commodus were demolished. His body was buried in the Mausoleum of Hadrian.

Commodus' death marked the end of the Nerva–Antonine dynasty. Commodus was succeeded by Pertinax, whose reign was short-lived; he would become the first claimant to be usurped during the Year of the Five Emperors.

In 195, the emperor Septimius Severus, trying to gain favour with the family of Marcus Aurelius, rehabilitated Commodus' memory and had the Senate deify him.[18]

Character and physical prowess

Character and motivations

Cassius Dio, a first-hand witness, describes him as "not naturally wicked but, on the contrary, as guileless as any man that ever lived. His great simplicity, however, together with his cowardice, made him the slave of his companions, and it was through them that he at first, out of ignorance, missed the better life and then was led on into lustful and cruel habits, which soon became second nature."[19]

His recorded actions do tend to show a rejection of his father's policies, his father's advisers, and especially his father's austere lifestyle, and an alienation from the surviving members of his family. It seems likely that he was brought up in an atmosphere of Stoic asceticism, which he rejected entirely upon his accession to sole rule.

After repeated attempts on Commodus' life, Roman citizens were often killed for making him angry. One such notable event was the attempted extermination of the house of the Quinctilii. Condianus and Maximus were executed on the pretext that, while they were not implicated in any plots, their wealth and talent would make them unhappy with the current state of affairs.[20] Another event—as recorded by the historian Aelius Lampridius—took place at the Roman baths at Terme Taurine, where the emperor had an attendant thrown into an oven after he found his bathwater to be lukewarm.[21][22]

Changes of name

His original name was Lucius Aelius Aurelius Commodus.[23] On his father's death in 180, Commodus changed this to Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Commodus, before changing back to his birth name in 191.[1]

Later that year he adopted as his full style Lucius Aelius Aurelius Commodus Augustus Herculeus Romanus Exsuperatorius Amazonius Invictus Felix Pius (the order of some of these titles varies in the sources). "Exsuperatorius" (the supreme) was a title given to Jupiter, and "Amazonius" identified him again with Hercules.

An inscribed altar from Dura-Europos on the Euphrates shows that Commodus' titles and the renaming of the months were disseminated to the furthest reaches of the Empire; moreover, that even auxiliary military units received the title Commodiana, and that Commodus claimed two additional titles: Pacator Orbis (pacifier of the world) and Dominus Noster (Our Lord). The latter eventually would be used as a conventional title by Roman emperors, starting about a century later, but Commodus seems to have been the first to assume it.[24]

Commodus and Hercules

Disdaining the more philosophic inclinations of his father, Commodus was extremely proud of his physical prowess. The historian Herodian, a contemporary, described Commodus as an extremely handsome man.[25] As mentioned above, he ordered many statues to be made showing him dressed as Hercules with a lion's hide and a club. He thought of himself as the reincarnation of Hercules, frequently emulating the legendary hero's feats by appearing in the arena to fight a variety of wild animals. He was left-handed and very proud of the fact.[26] Cassius Dio and the writers of the Augustan History say that Commodus was a skilled archer, who could shoot the heads off ostriches in full gallop, and kill a panther as it attacked a victim in the arena.

Commodus the gladiator

Commodus also had a passion for gladiatorial combat, which he took so far as to take to the arena himself, dressed as a secutor.[27] The Romans found Commodus' gladiatorial combats to be scandalous and disgraceful.[28] According to Herodian, spectators of Commodus thought it unbecoming of an emperor to take up arms in the amphitheater for sport when he could be campaigning against barbarians among other opponents of Rome. The consensus was that it was below his office to participate as a gladiator.[29] Popular rumors spread alleging he was actually the son, not of Marcus Aurelius, but of a gladiator whom his mother Faustina had taken as a lover at the coastal resort of Caieta.[30]

In the arena, Commodus' opponents always submitted to the emperor; as a result he never lost. Commodus never killed his gladiatorial adversaries, instead accepting their surrenders. His victories were often welcomed by his bested opponents, as bearing scars dealt by the hand of an Emperor were considered a mark of fortitude.[31] Citizens of Rome missing their feet through accident or illness were taken to the arena, where they were tethered together for Commodus to club to death while pretending they were giants.[32] Privately, it was also his custom to kill his opponents during practice matches.[33] For each appearance in the arena, he charged the city of Rome a million sesterces, straining the Roman economy.

Commodus was also known for fighting exotic animals in the arena, often to the horror and disgust of the Roman people. According to Cassius Dio, Commodus once killed 100 lions in a single day.[34] Later, he decapitated a running ostrich with a specially designed dart[35] and afterwards carried his sword and the bleeding head of the dead bird over to the Senators' seating area and motioned as though they were next.[36] Dio notes that the targeted senators actually found this more ridiculous than frightening, and chewed on laurel leaves to conceal their laughter.[37] On another occasion, Commodus killed three elephants on the floor of the arena by himself.[38] Finally, Commodus killed a giraffe, which was considered to be a strange and helpless beast.[39]

_01_(cropped).jpg) The Emperor Commodus Leaving the Arena at the Head of the Gladiators (detail) by Edwin Howland Blashfield (1848–1936), Hermitage Museum and Gardens, Norfolk, Virginia.

The Emperor Commodus Leaving the Arena at the Head of the Gladiators (detail) by Edwin Howland Blashfield (1848–1936), Hermitage Museum and Gardens, Norfolk, Virginia.

Media portrayals

- In 1964's The Fall of the Roman Empire, a fictionalized Commodus who serves as the main antagonist of the film is portrayed by Christopher Plummer.

- In 2000's Academy Award-winner for Best Picture, Gladiator, a fictionalized Commodus serves as the main antagonist of the film. He is played by the actor Joaquin Phoenix, in a performance which received a nomination in the Best Supporting Actor category at the 2001 Oscars.[40]

- A character in the 2013 video game Ryse: Son of Rome is named Commodus and is one of the main antagonists of the game. The son of Emperor Nero, he shares several traits with the historic Commodus.[41]

- In Rick Riordan's book series The Trials of Apollo, Commodus appears as one of the main antagonists, being part of the evil Triumvirate of deified Roman emperors.

- Commodus is a minor antagonist in the 2005 video game Colosseum: Road to Freedom. The player can fight Commodus in the game, who dresses as the god Hercules. The game takes liberties with the events surrounding his death, with the player being the one who actually kills him rather than the wrestler Narcissus.

- The 2017 Docu-drama mini-series Roman Empire: Reign of Blood retells his story.[42][43] In this version, Narcissus kills Commodus after learning that the Emperor's arena opponents had been armed only with edgeless swords. Though he strangles Commodus, it is after initially challenging him to a duel and does not occur in his bath but while he is preparing for it.

Nerva–Antonine family tree

Nerva–Antonine family tree | |

|---|---|

| |

| Notes:

Except where otherwise noted, the notes below indicate that an individual's parentage is as shown in the above family tree.

| |

References:

|

Ancestors

| Ancestry of Commodus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Hammond, pp. 32–33.

- RE Aurelius 89

- "Commodus". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- Historia Augusta – Life of Commodus 1

- Historia Augusta 12.8

- David L. Vagi Coinage and History of the Roman Empire Vol. One: History p.248

- Susan P. Mattern The Prince of Medicine: Galen in the Roman Empire p. xx

- Cassius Dio Roman History 71.33.1

- Anthony R Birley Marcus Aurelius: A Biography p.197

- Historia Augusta 1.6

- "Tulane University "Roman Currency of the Principate"".

- Dio Cassius 72.36.4, Loeb edition translated E. Cary

- Birley, Anthony R.; Birley, Anthony R. (1 June 2002). Septimius Severus: The African Emperor. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0203028599 – via Google Books.

- Colin Wells (2004) [1984, 1992]. The Roman Empire. Second Edition (sixth reprint edition). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-77770-0, p. 255.

- Dio Cassius 73.10.2, Loeb edition translated E. Cary

- "Roman Emperors – DIR commodus". www.roman-emperors.org.

- Dio Cassius 73.22.3

- To “accept kinship with Commodus ... the bluntly pragmatic decision was taken to deify the former emperor, thus legitimizing Severus’ seizure of power.” See Annelise Freisenbruch, Caesars' Wives: Sex, Power, and Politics in the Roman Empire (London and New York: Free Press, 2010), 187.

- Dio Cassius 73.1.2, Loeb edition translated E. Cary

- Dio Cassius 73.5.3, Loeb edition translated E. Cary

- Historia Augusta. C 1, 9. – Historia Augusta Bd. 1, eingeleitet und übersetzt von E. Hohl, bearbeitet und übersetzt von E. Merten (1976) 138. – E. Mer-ten, Bäder und Badegepflogenheiten in der Darstel-lung der Historia Augusta (Antiquitas. Reihe 4, Bd. 16. 1983) 123.

- Heinz, W. (1986). Die ''Terme Taurine'' von Civitavecchia – ein römisches Heilbad. Antike Welt, 17(4), 22–43.

- Hammond, p. 32.

- Spiedel, M. P (1993). "Commodus the God-Emperor and the Army". Journal of Roman Studies. 83: 109–114. doi:10.2307/300981. JSTOR 300981.

- Grant, Michael. The Roman Emperors (1985) p. 99.

- Dio, Cassius. Roman History: Epitome of Book LXXIII pp 111.

- Gibbon, Edward. The history of the decline and fall of the Roman Empire. Vol. 5. Methuen, 1898.

- Herodian's Roman History F.L. Muller Edition 1.15.7

- Echols, Edward C. "Herodian of Antioch's History of the Roman Empire." English translation) UCLA Press, Berkeley CA (1961), 1.15.1-9

- Historia Augusta, Life of Marcus Aurelius, XIX. The film The Fall of the Roman Empire makes use of this story: one of the characters is an old gladiator who eventually reveals himself to be Commodus' real father.

- Dio (Cassius.), and Earnest Cary. Roman History. Harvard University Press, 1961, 73.10.3

- Dio Cassius 73.20.3, Loeb edition translated E. Cary

- Dio Cassius 73.10.3

- Gibbon p.. 106 "disgorged at once a hundred lions; a hundred darts"

- Gibbon, Edward The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire: Volume I Everyman's Library (Knopf) New York. 1910. p. 106 "with arrows whose point was shaped in the form of a crescent"

- Lane Fox, Robin The Classical World: An Epic History from Homer to Hadrian Basic Books. 2006 p. 446 "brandishing a sword in one hand and bloodied neck...He gesticulated at the Senate."

- Roman History by Cassius Dio penelope.uchicago.edu

- Scullard, H. H The Elephant in the Greek and Roman World Thames and Hudson. 1974 p. 252

- Gibbon p. 107 "*1 Commodus killed a camelopardalis or giraffe ... the most useless of the quadrupeds".

- IMDb Commodus (Character) from Gladiator (2000) Retrieved October 2012

- Nichols, Derek (8 February 2014). "History Behind The Game – Ryse: Son of Rome". Venture Beat. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- Agius, Den (19 November 2016). "Box Set Binge: Roman Empire: Reign of Blood, The Path and Deutschland 83". What's on TV. TI Media Limited. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- O'Keefe, Meghan (25 November 2016). "'Roman Empire: Reign Of Blood': Who Was The Real Lucilla?". Decider. NYP Holdings, Inc. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

Sources

- , Encyclopædia Britannica, VI (9th ed.), New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1878, pp. 207–08.

- , Encyclopædia Britannica, VI (11th ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1911, p. 777.

Further reading

- Geoff W Adams, The Emperor Commodus : gladiator, Hercules or a tyrant?. Boca Raton: BrownWalker Press, [2013]. ISBN 1612337228

- G. Alföldy, "Der Friedesschluss des Kaisers Commodus mit den Germanen," Historia, 20 (1971), pp. 84–109.

- P. A. Brunt, "The Fall of Perennis: Dio-Xiphilinus 79.9.2," Classical Quarterly, 23 (1973), pp. 172–77

- J. Gagé, "La mystique imperiale et l'épreuve des jeux. Commode-Hercule et l'anthropologie hercaléenne," ANRW 2.17.2 (1981), 663–83

- Hammond, Mason (1957). "Imperial Elements in the Formula of the Roman Emperors during the First Two and a Half Centuries of the Empire". Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome. 25: 19–64. JSTOR 4238646.

- Olivier Hekster, Commodus: An Emperor at the Crossroads: Dutch monographs on ancient history and archaeology, 23. Brill, 2002. ISSN 0924-3550

- L. L. Howe, The Praetorian Prefect from Commodus to Diocletian (A.D. 180–305). Chicago, 1942

- M.P. Speidel, "Commodus the God-Emperor and the Army," Journal of Roman Studies, 83 (1993), pp. 109–14.

- Jerry Toner, The Day Commodus Killed a Rhino: Understanding the Roman Games. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Commodus. |

Commodus Born: 31 August 161 Died: 31 December 192 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Marcus Aurelius |

Roman emperor 180–192 |

Succeeded by Pertinax |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by T. Pomponius Proculus Vitrasius Pollio M. Flavius Aper II as ordinary consuls |

Consul of the Roman Empire 177 with Marcus Peducaeus Plautius Quintillus |

Succeeded by Servius Cornelius Scipio Salvidienus Orfitus, and Domitius Velius Rufus as ordinary consuls |

| Preceded by Servius Cornelius Scipio Salvidienus Orfitus, and Domitius Velius Rufus as ordinary consuls |

Consul of the Roman Empire 179 with Publius Martius Verus |

Succeeded by Titus Flavius Claudianus, and Lucius Aemilius Iuncus as suffect consuls |

| Preceded by Lucius Fulvius Rusticus Gaius Bruttius Praesens II, and Sextus Quintilius Condianus as ordinary consuls |

Consul of the Roman Empire 181 with Lucius Antistius Burrus |

Succeeded by Marcus Petronius Sura Mamertinus, and Quintus Tineius Rufus as ordinary consuls |

| Preceded by Marcus Petronius Sura Mamertinus, and Quintus Tineius Rufus as ordinary consuls |

Consul of the Roman Empire 183 with Gaius Aufidius Victorinus |

Succeeded by Lucius Tutilius Pontianus Gentianus, and ignotus as suffect consuls |

| Preceded by Triarius Maternus Lascivius, and Tiberius Claudius Marcus Appius Atilius Bradua Regillus Atticus |

Consul of the Roman Empire 186 with Manius Acilius Glabrio II |

Succeeded by Lucius Novius Rufus, and Lucius Annius Ravus as suffect consuls |

| Preceded by Domitius Iulius Silanus, and Quintus Servilius Silanus as suffect consuls |

Consul of the Roman Empire 190 with Marcus Petronius Sura Septimianus |

Succeeded by Lucius Septimius Severus, and Apuleius Rufinus as suffect consuls |

| Preceded by Popilius Pedo Apronianus, and Marcus Valerius Bradua Mauricus as ordinary consuls |

Consul of the Roman Empire 192 with Pertinax |

Succeeded by Quintus Pompeius Sosius Falco, and Gaius Julius Erucius Clarus Vibianus as ordinary consuls |